Abstract

Cardiac fibroblasts play a key role in fibrosis development in response to stress and injury. Angiotensin II (ANG II) is a major profibrotic activator whose downstream effects (such as phospholipase Cβ activation, cell proliferation, and extracellular matrix secretion) are mainly mediated via Gq-coupled AT1 receptors. Regulators of G protein signaling (RGS), which accelerate termination of G protein signaling, are expressed in the myocardium. Among them, RGS2 has emerged as an important player in modulating Gq-mediated hypertrophic remodeling in cardiac myocytes. To date, no information is available on RGS in cardiac fibroblasts. We tested the hypothesis that RGS2 is an important regulator of ANG II-induced signaling and function in ventricular fibroblasts. Using an in vitro model of fibroblast activation, we have demonstrated expression of several RGS isoforms, among which only RGS2 was transiently upregulated after short-term ANG II stimulation. Similar results were obtained in fibroblasts isolated from rat hearts after in vivo ANG II infusion via minipumps for 1 day. In contrast, prolonged ANG II stimulation (3–14 days) markedly downregulated RGS2 in vivo. To delineate the functional effects of RGS expression changes, we used gain- and loss-of-function approaches. Adenovirally infected RGS2 had a negative regulatory effect on ANG II-induced phospholipase Cβ activity, cell proliferation, and total collagen production, whereas RNA interference of endogenous RGS2 had opposite effects, despite the presence of several other RGS. Together, these data suggest that RGS2 is a functionally important negative regulator of ANG II-induced cardiac fibroblast responses that may play a role in ANG II-induced fibrosis development.

Keywords: collagen, cell proliferation, G proteins, myofibroblasts, phospholipase Cβ

cardiac fibroblasts are the most prevalent cell type in the myocardium (2, 38, 63) and play a central role in the maintenance of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the normal heart. Together with myocytes, they are key determinants of cardiac development, myocardial structure, cell signaling, and electromechanical function (3, 8, 48). In response to stress and in the injured and failing heart, fibroblasts phenotypically transform into “activated” myofibroblasts with characteristic changes in gene expression, morphology, and function (33, 42, 55). Myofibroblasts are the predominant cells responsible for collagen formation at sites of repair in the heart and fibrosis development (60), a major contributor to the cardiac remodeling response of the injured and diseased heart. Fibrosis can impair contractile function and electrical coupling of myocytes, which ultimately contribute to heart failure and predispose the heart to arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, respectively (51).

A key profibrotic activator of cardiac fibroblasts is angiotensin II (ANG II), which is produced by circulating and local renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems that are upregulated in response to mechanical stretch and other cardiac insults (5, 26, 51, 59). Adult rat cardiac fibroblasts express primarily AT1 receptors (12, 58): their stimulation activates Gq-mediated phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ) (13) and induces secretion of collagen and other ECM proteins (6, 58), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and other growth factors (10, 18, 32), and cell proliferation (4).

Gq family members and other heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins (G proteins) serve as central switch boards that transfer extracellular signals from G protein-coupled receptors across the plasma membrane to intracellular effectors and thereby determine signal transduction efficiency and specificity (39). They are tightly controlled by regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) (25, 46). The RGS family includes 20 canonical proteins that are grouped into four subfamilies based on primary sequence homology and the presence of additional domains (44, 67). RGS share a conserved RGS core domain that is both necessary and sufficient to confer GTPase activity by binding directly to active, GTP-bound Gα subunits (54). This results in acceleration of Gα GTPase activity and signal termination, as well as in some cases blocked Gα-mediated signal generation via effector antagonism (1, 22). Each cell type expresses a unique RGS complement. RGS expression profiles are primarily based on Northern blots, in situ hybridizations, and PCR analyses, because antibodies that unequivocally recognize endogenous RGS isoforms at the protein level are generally not available. Several canonical RGS are expressed in the mammalian myocardium (36, 43), as well as in cultured/isolated cardiac myocytes (14, 28). To date, no information is available on RGS expression in cardiac fibroblasts.

In the cardiovascular system, RGS2 has emerged as a key player in regulating G protein signaling in cardiac myocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells (56) and plays an important role in modulating Gq-mediated hypertrophy development (52, 66) and vascular tone (23, 53). Like other members of the B/R4 subfamily, RGS2 mainly consists of the RGS core domain with short NH2- and COOH-terminal extensions. In contrast, RGS2 regulates Gq proteins, whereas the others also target Gi/o (21). It has been proposed that RGS2 arose from the B/R4 subfamily to have specialized activity as a potent and selective Gαq GTPase-activating protein that modulates cardiovascular function (31). Importantly, RGS2 is highly regulated in its expression in many cell types (30), including cardiac myocytes (21) and vascular smooth muscle cells (19).

This study was designed to determine whether RGS2 is expressed in cardiac fibroblasts, to investigate its regulation by ANG II, and to test the hypothesis that RGS2 is an important regulator of ANG II-induced signaling and function in cardiac fibroblasts. We have demonstrated that RGS2 1) is expressed at comparable levels in fibroblasts and activated myofibroblasts from adult rat ventricles, 2) is dynamically regulated by ANG II both in vitro and in vivo, and 3) exerts an inhibitory effect on ANG II-induced PLCβ activity, collagen production, and cell proliferation. Moreover, we have identified several other RGS isoforms in cardiac fibroblasts that are not changed in their expression by ANG II.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and culture of adult rat ventricular cardiac fibroblasts.

All animal studies conformed to the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Vertebrate Animals in Research and Training, and all experimental protocols involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Rhode Island Hospital. Hearts were quickly excised from anesthetized male Sprague-Dawley rats (5 wk old), retrogradely perfused for 2 min in Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate (KHB) buffer containing (in mM) 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 11 glucose, and 8.4 HEPES at 37°C, and then switched to enzyme buffer 1 [KHB buffer containing 0.3 mg/ml collagenase II (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ), 0.3 mg/ml hyaluronidase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 50 μM CaCl2]. After 20 min, the ventricular tissue was isolated, minced, and further digested at 37°C for 18 min in enzyme buffer 1 supplemented with increased CaCl2 (500 μM), trypsin IX (0.6 mg/ml; Sigma), and deoxyribonuclease (0.6 mg/ml; Sigma). The cell suspension was then filtered into 10 ml of DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (complete medium) and centrifuged for 2 min at 20 g. The supernatant was removed from the pelleted myocytes and centrifuged again for 5 min at 800 g. The resulting fibroblast pellet was resuspended in complete medium and plated for 2 h, after which the medium was changed to remove unattached or loosely attached cells, including vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and a few remaining myocytes. Originally plated cells (P0) and the first two passages (P1 and P2, each obtained by trypsinization after 3 days in complete medium) were used in this study. Experiments in each passage were performed in six-well plates. Cells were maintained in complete medium until they were subjected to specific conditions described for each experiment. DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10 μg/ml insulin, 5.5 μg/ml transferrin, and 5 ng/ml sodium selenite (ITS; Sigma) was used as serum-free medium when indicated.

Immunofluorescent staining.

Fibroblasts plated on coverslips were maintained in complete medium for 72 h, fixed with 4% formaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS [15 min at room temperature (RT) each]. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with Image-IT FX signal enhancer (Invitrogen; 30 min at RT), followed by incubation (1 h at RT) with antibodies against vimentin (Sigma; 1:100), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; Sigma; 1:400), the embryonic form of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; 1:3,000), smooth muscle myosin (Sigma; 1:250), or von Willebrand factor (vWF; Sigma; 1:250), as well as Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen; 1:200). Coverslips were mounted with ProLong gold antifade reagent containing 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen).

Western blot analysis.

Fibroblasts were lysed for 30 min at 4°C in 1× lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Equal amounts of protein per lane were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide (Tris/glycine) gels (7% gels for procollagen detection) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After transfer, the membranes were stained with Ponceau S, blocked in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% nonfat dry milk, and probed with antibodies against vimentin (Sigma; 1:500), α-SMA (Sigma; 1:1,000), procollagen type I (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; 1:3,000), FLAG (M2; Sigma; 1:1,500), and β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:200). After three washes in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 and incubation with appropriate peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies, proteins of interest were visualized by chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Quantitative densitometry was performed using the public domain ImageJ program (developed at the U.S. National Institutes of Health and available online at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

PLCβ activity.

Fibroblasts were labeled with myo-[3H]inositol (2 μCi/well; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) in inositol-free DMEM medium (MP Biomedical, Solon, OH) with ITS for 20 h. On the assay day, LiCl (10 mM final) was added before addition of ANG II (0.3 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. Total inositol phosphates (IP) were extracted in 20 mM formic acid, neutralized, separated by anion exchange chromatography (Dowex AG1-X8; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and quantitated by liquid scintillation counting, as previously described (35). Each sample was assayed in triplicate.

Reverse transcription-PCR.

Total RNA (1 μg) extracted from fibroblasts was reverse transcribed and amplified using the SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) with RGS isoform-specific primers (Table 1). One-Step RT-PCR was performed at 50°C for 30 min and 94°C for 2 min and then at 94°C for 30 s, 48–56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min for a total of 30–40 cycles, followed by 72°C for 5 min. RT-PCR products were visualized on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels. RNA from adult rat cortex and adult ventricular myocytes were used for control and comparison, respectively.

Table 1.

RGS isoform-specific primers used for RT-PCR analysis

| Family | cDNA | GenBank Accession No. | Primer Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Annealing Temperature, °C | Product Size, bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/RZ | RGS 17 (RGSZ2) | AF_191555 | Forward GGAAACCAAAGGCCCAACAATAC | 54 | 350 |

| Reverse ATCATCCTGGCCTTTTCTTCAACA | |||||

| RGS 20 (RGSZ1) | NM_021374 | Forward AGAAGACCAGAGACCCCAAAGAGC | 54 | 434 | |

| Reverse AGTTCATGAAGCGGGGATAGGAGT | |||||

| B/R4 | RGS 2 | NM_053453 | Forward TCATGTAGCATGGGGCTCCG | 50 | 636 |

| Reverse ATGCAAAGTGCCATGTTCCTGG | |||||

| RGS 3 | NM_019340 | Forward CTGGAAAAGCTGCTGCTTCATA | 50 | 367 | |

| Reverse GACTCATCTTCTTCTGGTTAATG | |||||

| RGS 5 | NM_019341 | Forward GGAAAGGGCCAAAGAGATCAAG | 50 | 496 | |

| Reverse CTCCTTATAAAACTCAGAGCGC | |||||

| RGS 8 | AB_006013 | Forward GACAAACCCAACCGCGCTCTCAAG | 55 | 288 | |

| Reverse CGTGGCCTCTCGGGTCTGGAAATC | |||||

| RGS 18 | AY_651776 | Forward AACTAATGCACGGGTCAG | 48 | 577 | |

| Reverse CGCCTCCTAAGATTTGTTGG | |||||

| C/R7 | RGS 7 | AB_024398 | Forward ACCCATTTCTTGTACCGCCTGACC | 54 | 485 |

| Reverse TCTGCCCTTTCTCTTTGCCTGTAG | |||||

| RGS 11 | XM_573061 | Forward ACAAAGCTCCGCGTCGAGCGATG | 56 | 444 | |

| Reverse GTGCAGAGGCTTCCGCAAGAATGGG | |||||

| D/R12 | RGS 10 | XM_341936 | Forward TATCCACGATGGCGATGGGAG | 54 | 391 |

| Reverse CAAGAAGCGGCTGTAGCTGTC | |||||

| − | GAPDH | NM_017008 | Forward AGTGGATATTGTTGCCATCAATG | 50 | 830 |

| Reverse CCATGAGGTCCACCACCCTG | |||||

| − | β-Actin | NM_031144 | Forward AGATTACTGCTCTGGCTCCTA | 52 | 221 |

| Reverse CAAAGAAAGGGTGTAAAACG |

Primers used were specific for isoforms of regulators of G protein signaling (RGS), organized according to their 4 canonical subfamily affiliations. GAPDH and β-actin were used as internal controls.

Real-time PCR.

Reverse-transcribed (TaqMan reverse transcription reagents) RNA samples from fibroblasts were subjected to real-time PCR using FAM-labeled TaqMan probes for RGS2, RGS3, RGS5, GAPDH, and 18S and universal PCR master mix according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Each sample was assayed in duplicate in two independent PCR reactions and normalized to 18S expression. Samples without enzyme in the reverse transcription reaction or template during PCR served as negative controls. PCR cycling was performed at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min for a total of 40 cycles using ABI Prism 7500. The cycle threshold (CT) values corresponding to the PCR cycle number at which fluorescence emission in real time reaches a threshold above the baseline emission were determined using sequence detecting system software (SDS version 1.4; Applied Biosystems). Serial dilutions of cDNA plasmids for rat RGS2 and RGS5 (0.3–3 × 106 copies) confirmed the linearity of the resulting CT values.

Adenoviral gene transfer.

Adenovirus encoding NH2-terminally FLAG-tagged RGS2 (Ad-RGS2) was generated previously (21). Control adenovirus (Ad-Ctr) and a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing adenovirus (Ad-GFP) served as controls. Fibroblasts were cultured in complete medium and infected the next day. To ensure comparable multiplicity of infection (MOI) between passages with different growth rates, a representative well was trypsinized and counted. Appropriate amounts of adenovirus in DMEM/F12 containing 0.5 ml of ITS were then added to each well immediately after medium aspiration. Complete medium was added (1.5 ml) after 2 h.

RNA interference.

The short interfering RNA (siRNA) for RGS2 was previously generated with AAGGAAAATATACACCGACTT as target sequence (66). GAPDH siRNA and negative control siRNA without significant homology to any known rat gene (Applied Biosystems) served as controls. After optimization of the type/amount of transfection reagent and siRNA, the following conditions were determined to achieve effective gene suppression with a minimum amount of siRNA. Fibroblasts were cultured in complete medium and subjected to RNA interference (RNAi) the next day using siPORT amine transfection agent diluted in OPTI-MEM (Invitrogen). After 10 min of incubation at RT, 75 nM siRNA was added and incubated for another 10 min. The siRNA/siPORT amine transfection complexes were then dispensed onto the cells right after medium change with antibiotic-free DMEM/F12 containing 2% FBS (2 ml/well). Cellular siRNA uptake was visualized by fluorescent microscopy 2 days after transfection of Cy3-labeled siRNA (Applied Biosystems).

Total collagen assay.

After 20 h in serum-free medium, fibroblasts were incubated in ANG II (1 μM) for 48 h, lysed as described above, and sonicated for 3 × 5 s on ice. After centrifugation at 3,000 g, total collagen content was assayed in equal amounts of supernatant according to the manufacturer's instructions for the Sircol soluble collagen assay kit (Biocolor, Carrickfergus, County Antrim, UK). Briefly, supernatants were mixed with Sircol dye reagent for 30 min at RT. After centrifugation at 15,000 g for 10 min, the collagen-Sircol dye complex was precipitated, unbound dye was removed with the supernatant, and collagen-bound dye was subsequently released and quantitated via spectrophotometry at 540 nm. Normalization to protein concentrations gave similar results.

Cell proliferation.

Fibroblasts were cultured on coverslips and starved in serum-free medium for 20 h. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; 30 nM) was added immediately before addition of ANG II (1 μM). After 48 h, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and incorporated BrdU was identified with a mouse anti-BrdU antibody (Dako, Carpinteria, CA; 1:100) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen; 1:200). Coverslips were mounted as described above. Experiments were done in triplicate, and five images (with 300–400 cells) were taken randomly for each coverslip. Fibroblast proliferation was expressed as the percentage of BrdU-positive nuclei to DAPI-positive (total) nuclei.

Chronic ANG II infusion model.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (5–6 wk old) were anesthetized with ketamine and medetomidine (75 and 1 mg/kg body wt). Osmotic minipumps (Alzet, Cupertino, CA; models 1003D, 2001, or 2002) were used and primed in sterile 0.9% saline at 37°C overnight to ensure immediate delivery of ANG II (555 ng·kg−1·min−1) or 0.9% saline after subcutaneous implantation. After surgery, the animals received regular chow with 0.4% KCl in drinking water. At the indicated time points (5 h to 2 wk), hearts were removed for isolation of ventricular fibroblasts and myocytes to investigate the RGS2 expression or processed for histology.

Gomori trichrome stain.

Cross sections (5 μm) of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded hearts were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through ethanol gradient solutions to PBS, and treated with Bouin's solution (Sigma). They were then stained with Weigert's iron hematoxylin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for 10 min, followed by trichrome stain for 20 min. After dehydration, slides were mounted with SHUR/Mount toluene-based mounting medium (Triangle Biomedical Sciences, Durham, NC).

Statistical analysis.

Data from representative assays are shown and expressed as means ± SD for n determinations (unless indicated otherwise). Statistical differences were assessed using unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test or two-way ANOVA for comparison of individual means. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In vitro model of cardiac fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.

In response to stress, cardiac fibroblasts undergo three phenotypic changes: they convert into activated (i.e., contractile and hypersecretory) myofibroblasts, proliferate, and produce ECM components (such as collagen I and III) (42, 55). In this study, we used the first three passages (P0–P2) of ventricular fibroblasts isolated from 5-wk-old rats under experimental conditions that mimic these changes.

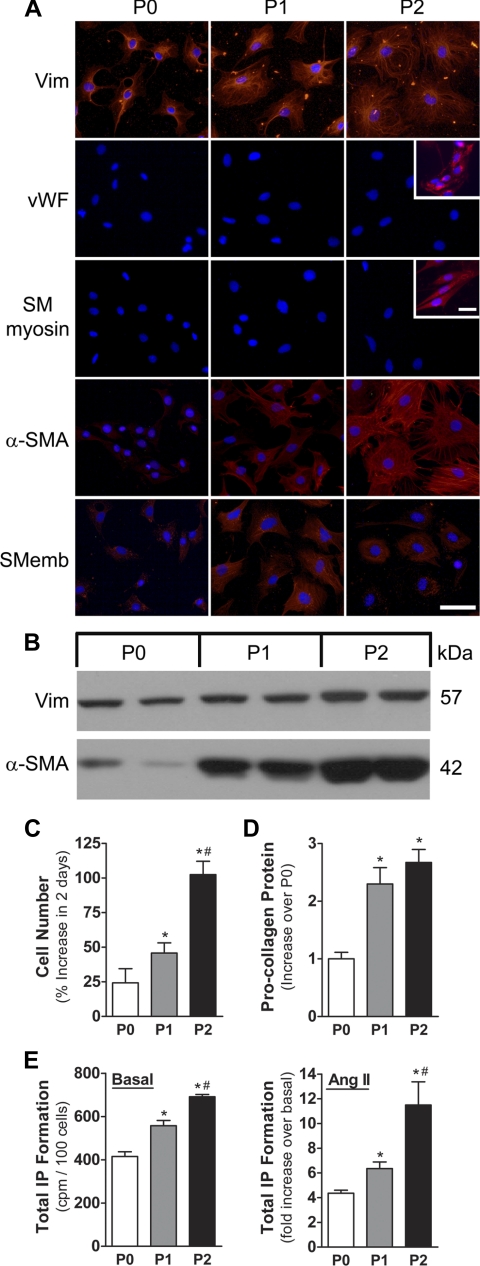

First, we determined the purity of the cell preparations: cells in all three passages expressed vimentin at comparable levels (Fig. 1, A and B) but were negative for smooth muscle myosin and vWF, indicating the absence of vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells, respectively (Fig. 1A). Cardiac myocytes, which can be easily identified by their rod shape, were also not present.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of in vitro model of cardiac fibroblasts. A: immunofluorescent staining (red) with the indicated antibodies of adult rat ventricular fibroblasts when originally plated (P0) and at the first 2 passages (P1 and P2). Nuclei (blue) were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Scale bar, 50 μm. Insets: vascular endothelial cells and human aortic smooth muscle cells were used as positive controls for von Willebrand factor (vWF) and smooth muscle myosin (SM myosin). Scale bar, 25 μm. B: Western blots of fibroblast cell lysates (15 μg/lane) probed with the indicated antibodies. C: increase in cell numbers in P0–P2 after 2 days in complete medium (n = 4 each). D: procollagen type I in lysates from P0–P2 fibroblasts after 72 h in complete medium. Data are normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to P0 (n = 3 each). E: basal (left) and angiotensin II (ANG II; 0.3 μM, 30 min)-induced (right) total inositol phosphate (IP) formation (n = 3 each). *P < 0.05, P1 or P2 vs. P0. #P < 0.05, P2 vs. P1. Vim, vimentin; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; SMemb, embryonic form of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain.

Using surrogate markers for myofibroblasts (15, 33, 55), we delineated the timing and extent of phenotypic changes of fibroblast across the three passages: α-SMA and the embryonic form of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain were expressed at very low levels in P0 cells and markedly increased in P1 and P2 fibroblasts (Fig. 1, A and B). P1/P2 cells were also significantly larger and contained an increasing amount of α-SMA-positive stress fibers (Fig. 1A), suggesting progressive transformation of fibroblasts into activated myofibroblasts from P0 to P1/P2. Consistent with this notion, cell numbers (Fig. 1C) and procollagen type I expression (Fig. 1D) were increased in P1 and P2 compared with P0. Total IP formation normalized to cell numbers in each passage was measured as a reflection of PLCβ activity: both basal and ANG II-induced PLCβ activity showed a gradual increase from P0 to P2 (Fig. 1E). Thus the first three passages of freshly isolated adult ventricular fibroblasts recapitulate key phenotypic features of fibroblasts (P0) and myofibroblasts (P1/P2).

Transient RGS2 upregulation in response to short-term ANG II stimulation.

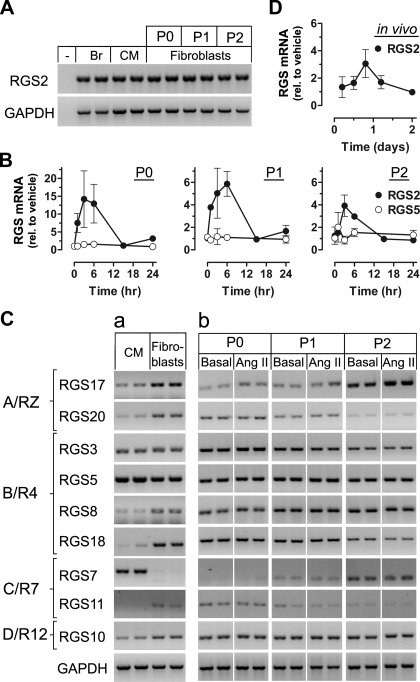

Using RT-PCR, we found that RGS2 is expressed in cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 2A). Its mRNA level was comparable to that of myocytes (isolated from the same heart) and brain and was not significantly changed between cell passages. In response to short-term stimulation with ANG II, RGS2 mRNA was transiently upregulated as shown by real-time PCR (Fig. 2B). Of note, TGF-β, which is enhanced in its expression by ANG II (29), also increased RGS2 expression (see Supplemental Fig. S1 for 6-h stimulation; supplemental material for this article is available online at the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology website), and its effect was transient within 24 h (data not shown). Both ANG II and TGF-β effects were more pronounced in P0 than in P1 and P2.

Fig. 2.

Transient and selective regulator of G protein signaling 2 (RGS2) mRNA upregulation in response to short-term stimulation with ANG II. A: RT-PCR analysis of RGS2 expression in P0–P2 fibroblasts and comparison with rat brain (Br) and adult cardiac myocytes (CM) from the same ventricle. Minus sign denotes absence of template. GAPDH was used as internal control. B: real-time PCR analysis of RGS2 expression (RGS5 shown for comparison) in P0–P2 fibroblasts that were maintained in complete medium for 48 h, followed by 20 h of serum starvation and stimulation with ANG II (1 μM) for the indicated times. Data (means ± SE, n = 2–4) are normalized to 18S and expressed relative to vehicle-treated controls (set as 1). Note the difference in y-axes between P0 and P1/P2. C: RT-PCR analysis of other RGS (organized according to their subfamily affiliations) in CM and P0 fibroblasts (a) and P0–P2 fibroblasts (b) maintained in complete medium for 48 h, followed by 20 h of serum starvation and 2 h of stimulation with ANG II (1 μM). Images in each row of b are from the same gel; spaces indicate removal of lanes with other conditions. D: real-time PCR analysis of RGS2 expression in freshly isolated cardiac fibroblasts from rats subjected to subcutaneous ANG II infusion (555 ng·kg−1·min−1) for the indicated days (n = 3–4 each).

We asked whether other RGS are expressed and regulated by ANG II. Figure 2Ca shows that members of all four canonical RGS subfamilies are expressed in cardiac fibroblasts. Depending on the isoform but unrelated to the subfamily, their expression was equal (RGS3), higher (RGS8, RGS10, RGS11, RGS17, RGS18, RGS20), or lower (RGS5 and RGS7) than in myocytes. Importantly, in contrast to RGS2, the other RGS were not altered in response to ANG II stimulation (Fig. 2Cb; see also Fig. 2B for RGS5).

Transient upregulation of RGS2 was also observed in cardiac fibroblasts that were freshly isolated from rats that had been subjected to subcutaneous ANG II infusion in vivo for less than 2 days (Fig. 2D). These findings demonstrate the presence of RGS2 mRNA in cardiac fibroblasts at a level comparable to that in myocytes and selective transient RGS2 upregulation in response to short-term ANG II stimulation both in vitro and in vivo.

Selective RGS2 downregulation in response to prolonged ANG II stimulation.

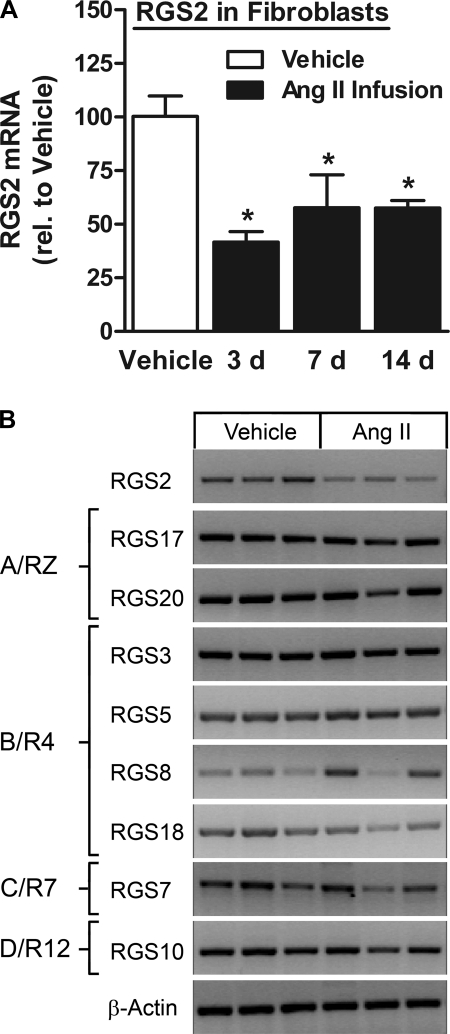

The in vivo model provided an opportunity to also investigate the effect of prolonged ANG II stimulation on RGS2 mRNA expression levels. After the transient rise within a day of subcutaneous ANG II infusion (see above), RGS2 was markedly downregulated as early as 3 days after ANG II pump insertion and until at least 14 days (end of study) (Fig. 3A). We also observed RGS2 downregulation in cardiac myocytes after prolonged ANG II stimulation in vivo (64 ± 12% of vehicle control after 3 days, P < 0.05; 67 ± 29% of vehicle control after 14 days, P = 0.18; n = 3 each), which followed transient RGS2 upregulation (2.2 ± 0.5 fold, n = 6, P < 0.05) after 18 h of ANG II stimulation.

Fig. 3.

Selective RGS2 downregulation in response to prolonged ANG II stimulation in vivo. A: real-time PCR analysis of RGS2 expression in freshly isolated cardiac fibroblasts from rats subjected to subcutaneous ANG II infusion (555 ng·kg−1·min−1) for the indicated days (n = 3 each). *P < 0.05, ANG II vs. vehicle. B: RT-PCR analysis of RGS2 and other RGS (organized according to their subfamily affiliations) in freshly isolated cardiac fibroblasts from rats subjected to subcutaneous ANG II infusion for 7 days. β-Actin was used as internal control.

We excluded the possibility that ANG II may be degraded over time by demonstrating that the efficacy in activating PLCβ activity in cultured fibroblasts (P2 cells) was comparable between ANG II that was extracted from the minipumps 5 days after insertion and ANG II that was freshly prepared on the day of the assay [1,697 ± 141 vs. 1,635 ± 56 counts per minute per 6 wells (cpm/6 wells), n = 3 each, not significant; basal 305 ± 14 cpm/6 wells]. Proper drug release was also confirmed. Subsequently, for the 2-wk time point, pumps were exchanged twice after 5 days each.

In contrast to RGS2, the other RGS isoforms were not altered, as shown for the 7-day time point in Fig. 3B. As expected, ANG II infusion for 2 wk induced cardiac hypertrophy (Supplemental Fig. S2A), indicated by an increase in ventricular weight/body weight and expression of atrial natriuretic factor and by interstitial and perivascular fibrosis (Supplemental Fig. S2B). Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-9, and MMP-13 mRNA levels were unchanged (Supplemental Fig. S2C), but altered activity cannot be excluded.

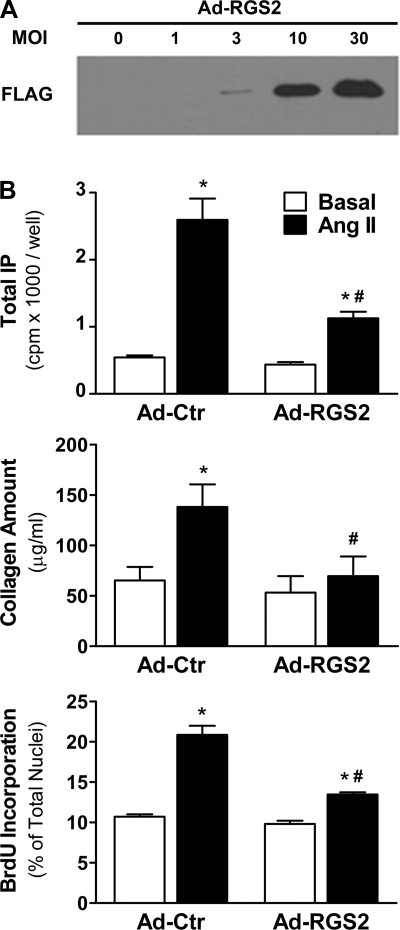

RGS2 overexpression inhibits ANG II-induced effects in cardiac fibroblasts.

To investigate the functional effects of increased RGS2 expression, we overexpressed RGS2 in P0–P2 cells via adenoviral gene transfer. We did not observe any apparent changes in cell morphology or viability after adenoviral gene transfer with different MOIs (MOIs 1, 3, and 10; data not shown). As expected, the infection efficiency in fibroblasts was dependent on the MOI, as shown with Ad-GFP for P1 cells in Supplemental Fig. S3A (similar results were obtained in P0 and P2). Accordingly, FLAG-tagged RGS2 protein expression could be titrated (Fig. 4A). The characteristic ANG II-induced rise in IP formation in cells infected with Ad-Ctr was dose-dependently inhibited on Ad-RGS2 infection at MOIs 1, 3, and 10 (shown for P1 cells in Supplemental Fig. S3B, top). At MOI 10, RGS2 inhibited IP formation by 65–75% in all three passages (Supplemental Fig. S3B, bottom).

Fig. 4.

Functional effects of RGS2 overexpression. A: representative Western blot (probed with an anti-FLAG-antibody) containing lysates from P1 fibroblasts infected with adenovirus encoding FLAG-tagged RGS2 (Ad-RGS2) for 48 h at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI). B: basal and ANG II-induced phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ) activity (0.3 μM ANG II, 0.5 h; top), collagen amount (1 μM, 48 h; middle), and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (1 μM, 48 h; bottom) 72 h after infection with Ad-RGS2 or control adenovirus (Ad-Ctr) (n = 3 each). *P < 0.05, ANG II vs. basal. #P < 0.05, Ad-RGS2 vs. Ad-Ctr.

RGS2 expression negatively regulated ANG II-induced PLCβ activity, total collagen production, and cell proliferation in adult ventricular fibroblasts: the ANG II-induced rise in IP formation was reduced from 4.8-fold in Ad-RGS2-infected cells to 2.6-fold in control cells (Fig. 4B, top). Similarly, a 2.1-fold rise in total collagen production in response to ANG II stimulation was reduced to 1.3-fold over basal in Ad-RGS2-infected cells (Fig. 4B, middle), and a 1.9-fold rise in BrdU incorporation was inhibited to 1.4-fold (Fig. 4B, bottom). RGS2 had no significant effect on basal PLCβ activity, total collagen production, or cell proliferation.

RGS2 knockdown enhances ANG II-induced effects in cardiac fibroblasts.

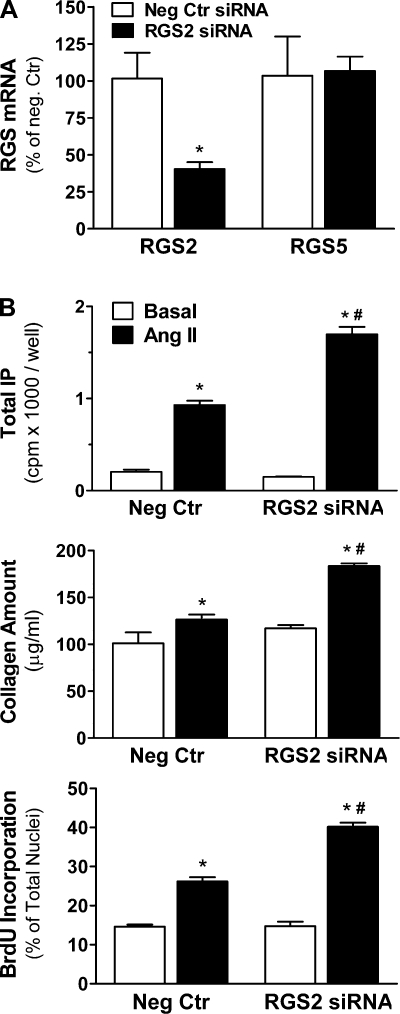

We used RNAi to examine the functional consequences of downregulation of endogenous RGS2. Phase-contrast and fluorescent images of fibroblasts transfected with Cy3-labeled siRNA show uniform cellular siRNA uptake that was detectable in more than 95% of cells, with no apparent changes in cell viability or morphology (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Compared with cells transfected with negative control siRNA, we were able to achieve up to 80% reduction in GAPDH mRNA (Supplemental Fig. S4B) and up to 60% reduction in RGS2 mRNA (Fig. 5A) using gene-specific siRNAs. Importantly, mRNA expression of other isoforms such as RGS5 (Fig. 5A) and RGS3 (data not shown) was not changed in cells transfected with RGS2 siRNA.

Fig. 5.

Functional effects of RGS2 RNA interference. A: RGS2 and RGS5 mRNA (real-time PCR, n = 3 each) 72 h after short interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection (75 nM). *P < 0.05, RGS2 vs. negative control (Neg Ctr) siRNA. B: basal and ANG II-induced PLCβ activity (0.3 μM ANG II, 0.5 h; top), collagen amount (1 μM, 48 h; middle), and BrdU incorporation (1 μM, 48 h; bottom) 72 h after RGS2 or Neg Ctr siRNA transfections (n = 3 each). *P < 0.05, ANG II vs. basal. #P < 0.05, RGS2 siRNA vs. Neg Ctr siRNA.

Selective reduction in RGS2 expression markedly enhanced ANG II-induced PLCβ activity, cell proliferation, and total collagen production: Gq-mediated IP formation over basal was increased from 4.5-fold in control cells to 11.4-fold in RGS2 siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 5B, top). In addition, RGS2 RNAi increased ANG II-induced total collagen production (Fig. 5B, middle) and fibroblast proliferation (Fig. 5B, bottom) from 1.2- and 1.8-fold in control cells to 1.6- and 2.7-fold in RGS2 siRNA-transfected cells, respectively. RGS2 RNAi had no significant effect on basal PLCβ activity, total collagen production, or cell proliferation.

DISCUSSION

ANG II is a well known profibrotic factor in many mammalian species, including humans (29). The majority of downstream effects are mediated via Gq-coupled AT1 receptors. RGS2 is an important regulator of Gq signaling in cardiac myocytes; however, no information is available for cardiac fibroblasts. We therefore investigated RGS2 expression, regulation, and function, using rat ventricular fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in the presence or absence of ANG II in vitro, as well as ANG II infusion in vivo, combined with molecular gain- and loss-of-function approaches. We have demonstrated that RGS2 expression is uniquely susceptible to ANG II-induced dynamic and biphasic regulation in vitro and in vivo and have shown that RGS2 is a functionally important negative regulator of ANG II-induced signaling and functional effects in cardiac fibroblasts despite the presence of several other RGS.

Experimental models.

Primary isolates of fibroblasts from the heart and other organs are widely used to study their signaling properties and cellular functions under defined experimental conditions. The purity of the cell preparations for our in vitro model was confirmed by positive staining for vimentin and the absence of staining for endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cell markers. The first three passages represent different fibroblast phenotypes (Fig. 1): consistent with two other reports (16, 34), P0 cells that had a fibroblast-like appearance gradually converted into myofibroblast-like phenotype after plating at 200 cells/mm2 and dual passage for 3 days each in complete medium, as evidenced by expression of smooth muscle cell markers (α-SMA and embryonic form of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain) and the presence of stress fibers (24). In addition, P1 and P2 cells increased in number more than P0 cells and had increased procollagen type I expression as well as basal and ANG II-stimulated PLCβ activity, which is consistent with a myofibroblast phenotype.

Myofibroblasts are typically not found in normal cardiac tissue but appear at sites of tissue repair (33). In contrast to other tissues, they persist in the myocardium long after the injury (61). The origin of myofibroblasts in the heart is still a matter of debate (64). Suspected sources include resident fibroblasts (62), endothelial cells (65), and bone marrow-derived hematopoietic precursor cells (17, 57). Our observations support the conventional view that resident fibroblasts in the heart can transform into myofibroblasts and suggest that circulating precursor cells may not be an absolute requirement. However, cell fate mapping studies are needed to determine the role of resident fibroblasts as source for activated myofibroblasts in vivo (64).

Subcutaneous ANG II infusion via osmotic minipumps was used to determine whether effects in vitro could also be observed in vivo. Moreover, it enabled us examine the effects of prolonged ANG II stimulation. This in vivo model has been used widely in the literature to investigate cardiac remodeling with ANG II delivery rates from 150 to 1,000 ng·kg−1·min−1 in rodents (4, 9). We chose 555·kg−1·min−1 for this study, as previously described (50), because in male Sprague-Dawley rats infused with ANG II at 500 ng·kg−1·min−1, plasma ANG II levels were shown to increase 6-fold compared with controls (11), which is in the same range (7-fold increase) as seen in heart failure patients (40). Consistent with other reports (27, 49, 50), ANG II infusion induced interstitial and perivascular fibrosis in the myocardium, as well as cardiac hypertrophy (Supplemental Fig. S2).

RGS2 expression and regulation in cardiac fibroblasts.

In the present study, we demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo that RGS2 is transiently upregulated in fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in response to short-term ANG II stimulation (Fig. 2). TGF-β had a similar effect in vitro (Supplemental Fig. S1). Importantly, on prolonged ANG II infusion in vivo, we observed marked RGS2 downregulation in cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 3). A similar biphasic regulation of RGS2 was also observed in cardiomyocytes from the same hearts, consistent with previous studies on RGS2 regulation in cardiac myocytes in response to short-term and prolonged activation of the Gq signaling pathway (21, 68). Ascending aortic constriction also leads to marked RGS2 downregulation in ventricular tissues, but cell type-specific RGS2 expression was not examined (66).

Further work is needed to determine the mechanisms for the observed biphasic RGS2 regulation in cardiac fibroblasts on ANG II stimulation. Our data suggest that TGF-β may be involved. Reports in other cell types suggest that protein kinase C (PKC)- and Ca2+-dependent mechanisms participate in RGS2 upregulation after acute stimulation of the Gq signaling pathway (30, 47). Much less is known about the mechanisms of RGS2 downregulation. Prolonged activation of PKC can lead to its downregulation, thereby potentially reducing a stimulus for RGS2 expression. However, possible contributions of this and/or other mechanisms to the downregulation of RGS2 expression have yet to be elucidated and were beyond the scope of this study.

RGS2 function in cardiac fibroblasts.

It is well known that enhanced Gq-mediated signal transduction in fibroblasts leads to an increase in cell proliferation and total collagen production, both of which are profibrotic effects (5). Expression of exogenous RGS2 was sufficient to inhibit ANG II-induced PLCβ activity, fibroblast proliferation, and total collagen production (Fig. 4). Conversely, knockdown of endogenous RGS2 markedly increased all three parameters (Fig. 5), indicating that endogenous RGS2 exerts important inhibitory effects despite the unperturbed presence of other RGS with potentially overlapping function (see below).

Given that RGS2 is a potent negative regulator of Gq in many cell types, RGS2 upregulation in response to short-term increase in Gq signaling is generally viewed as a negative feedback mechanism (30). In this study, it was more pronounced in nonactivated fibroblasts (P0) than in myofibroblasts (P1/P2), suggesting less negative regulation of Gq signaling by RGS2 in myofibroblasts under short-term ANG II stimulation.

The extent of RGS2 down-regulation after prolonged ANG II infusion (42–58% reduction) was comparable to what we achieved by RNAi in vitro (59% reduction). Functionally, fibroblasts in vitro responded with enhanced profibrotic ANG II effects on cell proliferation and total collagen production, suggesting that RGS2 may play a role in exacerbating fibrosis development in the stressed or injured heart with enhanced ANG II stimulation (see also below). Further investigations are needed to evaluate the role of RGS2 in regulating collagen production and/or degradation. Importantly, RGS2 downregulation in cardiac myocytes in response to enhanced Gq signaling has been implicated to increase the hypertrophic response in vitro (66) and in vivo (52). Thus the extent and timing of RGS2 regulation appears to play a role in both aspects of the cardiac remodeling response to stress.

Other RGS in cardiac fibroblasts.

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of canonical RGS expression in cardiac fibroblasts. We report expression of members of each subfamily in cardiac fibroblasts, which differed substantially from cardiac myocytes. In addition, several isoforms appeared to be altered in their expression during fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transformation in vitro (see basal conditions in Fig. 2C). For example, RGS11, RGS18, and RGS20 were decreased, whereas RGS7 and RGS17 were increased. Much work needs to be done to delineate the functional role of each RGS isoform in cardiac fibroblasts and myofibroblasts both in vitro and in vivo.

Although the A/RZ and C/R7 subfamily members expressed are selective for Gαi/o proteins, all B/R4 members accelerate GTPase activity for Gαq proteins (46). In addition, RGS10 (D/R12) was shown to regulate Gq signaling (45). The fact that selective RGS2 downregulation led to enhanced Gq-mediated signaling and function (Fig. 5) suggests that the function of RGS2 cannot be taken over by other Gq-regulating RGS expressed in cardiac fibroblasts. Importantly, the other RGS isoforms were not subject to regulation by ANG II (Figs. 2 and 3), highlighting a unique susceptibility of RGS2 to regulation (21).

Conclusions and outlook.

Together, the results from the present study identify RGS2 as a novel negative regulator of ANG II-induced signaling and function in adult cardiac fibroblasts that is functionally important and highly regulated by ANG II. RGS2 upregulation after short-term ANG II stimulation might represent a brief period of negative feedback for Gq-mediated events, which is diminished in myofibroblasts. RGS2 downregulation on prolonged ANG II stimulation might facilitate the development of Gq-mediated fibrosis.

Therapeutic benefits of reduction of ANG II production and/or AT1 receptor blockade in heart failure are to a significant extent derived from actions on cardiac fibroblasts and fibrotic remodeling (7). Other Gq-coupled receptors [e.g., endothelin receptors (37)] play a role in mediating fibrosis, as well. It is therefore conceivable that RGS2 may emerge as a therapeutic target in cardiac fibroblasts (in addition to myocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells), because it mitigates signaling at the G protein level.

Further investigations are required to delineate the physiological and pathophysiological role of RGS2 in regulating fibroblast behavior and fibrosis development in vivo. To that end, studies in primary fibroblasts from normal and diseased hearts, as well as transgenic and knockout approaches, particularly during cardiac remodeling and fibrosis in response to stress, are needed. However, cardiac fibroblast-specific gene-targeting experiments have been hampered by the lack of identification of suitable promoter elements (41). In a mouse model with global RGS2 deletion, pressure overload was shown to be associated with increased fibrosis (52). However, because RGS2 is ubiquitous with prominent expression in the vasculature and nervous system in addition to the heart, RGS2 knockout mice have a multifaceted phenotype that includes hypertension (23, 53) and an exaggerated hypertrophic response to pressure overload or myocyte-specific transgenic Gαq expression (52). An increase in autonomic tone has also been suggested (20). Thus it is not possible to discern whether an increased fibrotic response observed in this model is due to the absence of RGS2 in cardiac fibroblasts or an indirect effect resulting from RGS2 deletion in other cell types. Therefore, animal models with RGS2 modifications restricted to fibroblasts will be required to fully delineate the role of RGS2 for fibrosis development in the heart in vivo.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-72174 and HL-80127 (to U. Mende) and American Heart Association Award 0740098N (to U. Mende).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Ian Dixon (St. Boniface General Hospital Research Centre, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada) for helpful discussions and advice in setting up the fibroblast cultures. We thank Leonard Chavez, Jr., for participation in osmotic minipump implantations and Lisa Rickey for the stain in Supplemental Fig. S2B.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anger T, Zhang W, Mende U. Differential contribution of GTPase activation and effector antagonism to the inhibitory effect of RGS proteins on Gq-mediated signaling in vivo. J Biol Chem 279: 3906–3915, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banerjee I, Fuseler JW, Price RL, Borg TK, Baudino TA. Determination of cell types and numbers during cardiac development in the neonatal and adult rat and mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1883–H1891, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baudino TA, Carver W, Giles W, Borg TK. Cardiac fibroblasts: friend or foe? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1015–H1026, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bouzegrhane F, Thibault G. Is angiotensin II a proliferative factor of cardiac fibroblasts? Cardiovasc Res 53: 304–312, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brilla CG. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and myocardial fibrosis. Cardiovasc Res 47: 1–3, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brilla CG, Zhou G, Rupp H, Maisch B, Weber KT. Role of angiotensin II and prostaglandin E2 in regulating cardiac fibroblast collagen turnover. Am J Cardiol 76: 8D–13D, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown RD, Ambler SK, Mitchell MD, Long CS. The cardiac fibroblast: therapeutic target in myocardial remodeling and failure. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 45: 657–687, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camelliti P, Borg TK, Kohl P. Structural and functional characterisation of cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res 65: 40–51, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Campbell SE, Janicki JS, Weber KT. Temporal differences in fibroblast proliferation and phenotype expression in response to chronic administration of angiotensin II or aldosterone. J Mol Cell Cardiol 27: 1545–1560, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campbell SE, Katwa LC. Angiotensin II stimulated expression of transforming growth factor-β1 in cardiac fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 29: 1947–1958, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cassis LA, Marshall DE, Fettinger MJ, Rosenbluth B, Lodder RA. Mechanisms contributing to angiotensin II regulation of body weight. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 274: E867–E876, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crabos M, Roth M, Hahn AW, Erne P. Characterization of angiotensin II receptors in cultured adult rat cardiac fibroblasts. Coupling to signaling systems and gene expression. J Clin Invest 93: 2372–2378, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dostal DE. The cardiac renin-angiotensin system: novel signaling mechanisms related to cardiac growth and function. Regul Pept 91: 1–11, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Doupnik CA, Xu T, Shinaman JM. Profile of RGS expression in single rat atrial myocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1522: 97–107, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frangogiannis NG, Michael LH, Entman ML. Myofibroblasts in reperfused myocardial infarcts express the embryonic form of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMemb). Cardiovasc Res 48: 89–100, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freed DH, Cunnington RH, Dangerfield AL, Sutton JS, Dixon IM. Emerging evidence for the role of cardiotrophin-1 in cardiac repair in the infarcted heart. Cardiovasc Res 65: 782–792, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fujita J, Mori M, Kawada H, Ieda Y, Tsuma M, Matsuzaki Y, Kawaguchi H, Yagi T, Yuasa S, Endo J, Hotta T, Ogawa S, Okano H, Yozu R, Ando K, Fukuda K. Administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after myocardial infarction enhances the recruitment of hematopoietic stem cell-derived myofibroblasts and contributes to cardiac repair. Stem Cells 25: 2750–2759, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gao X, He X, Luo B, Peng L, Lin J, Zuo Z. Angiotensin II increases collagen I expression via transforming growth factor-beta1 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase in cardiac fibroblasts. Eur J Pharmacol 606: 115–120, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grant SL, Lassegue B, Griendling KK, Ushio-Fukai M, Lyons PR, Alexander RW. Specific regulation of RGS2 messenger RNA by angiotensin II in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol 57: 460–467, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gross V, Tank J, Obst M, Plehm R, Blumer KJ, Diedrich A, Jordan J, Luft FC. Autonomic nervous system and blood pressure regulation in RGS2-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R1134–R1142, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hao J, Michalek C, Zhang W, Zhu M, Xu X, Mende U. Regulation of cardiomyocyte signaling by RGS proteins: differential selectivity towards G proteins and susceptibility to regulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 41: 51–61, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hepler JR, Berman DM, Gilman AG, Kozasa T. RGS4 and GAIP are GTPase-activating proteins for Gqα and block activation of phospholipase Cβ by γ-thio-GTP-Gqα. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 428–432, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heximer SP, Knutsen RH, Sun X, Kaltenbronn KM, Rhee MH, Peng N, Oliveira-dos-Santos A, Penninger JM, Muslin AJ, Steinberg TH, Wyss JM, Mecham RP, Blumer KJ. Hypertension and prolonged vasoconstrictor signaling in RGS2-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 111: 445–452, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hinz B, Gabbiani G. Cell-matrix and cell-cell contacts of myofibroblasts: role in connective tissue remodeling. Thromb Haemost 90: 993–1002, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hollinger S, Hepler JR. Cellular regulation of RGS proteins: modulators and integrators of G protein signaling. Pharmacol Rev 54: 527–559, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holtz J. Pathophysiology of heart failure and the renin-angiotensin-system. Basic Res Cardiol 88, Suppl 1: 183–201, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang XR, Chung AC, Yang F, Yue W, Deng C, Lau CP, Tse HF, Lan HY. Smad3 mediates cardiac inflammation and fibrosis in angiotensin II-induced hypertensive cardiac remodeling. Hypertension 55: 1165–1171, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kardestuncer T, Wu H, Lim AL, Neer EJ. Cardiac myocytes express mRNA for ten RGS proteins: changes in RGS mRNA expression in ventricular myocytes and cultured atria. FEBS Lett 438: 285–288, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kawano H, Do YS, Kawano Y, Starnes V, Barr M, Law RE, Hsueh WA. Angiotensin II has multiple profibrotic effects in human cardiac fibroblasts. Circulation 101: 1130–1137, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kehrl JH, Sinnarajah S. RGS2: a multifunctional regulator of G-protein signaling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 34: 432–438, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kimple AJ, Soundararajan M, Hutsell SQ, Roos AK, Urban DJ, Setola V, Temple BR, Roth BL, Knapp S, Willard FS, Siderovski DP. Structural determinants of G-protein α subunit selectivity by regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2). J Biol Chem 284: 19402–19411, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee AA, Dillmann WH, McCulloch AD, Villarreal FJ. Angiotensin II stimulates the autocrine production of transforming growth factor-β1 in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 27: 2347–2357, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Manabe I, Shindo T, Nagai R. Gene expression in fibroblasts and fibrosis: involvement in cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res 91: 1103–1113, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Masur SK, Dewal HS, Dinh TT, Erenburg I, Petridou S. Myofibroblasts differentiate from fibroblasts when plated at low density. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 4219–4223, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mende U, Kagen A, Meister M, Neer EJ. Signal transduction in atria and ventricles of mice with transient cardiac expression of activated G protein αq. Circ Res 85: 1085–1091, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mittmann C, Chung CH, Hoppner G, Michalek C, Nose M, Schuler C, Schuh A, Eschenhagen T, Weil J, Pieske B, Hirt S, Wieland T. Expression of ten RGS proteins in human myocardium: functional characterization of an upregulation of RGS4 in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 55: 778–786, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Motte S, McEntee K, Naeije R. Endothelin receptor antagonists. Pharmacol Ther 110: 386–414, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nag AC. Study of non-muscle cells of the adult mammalian heart: a fine structural analysis and distribution. Cytobios 28: 41–61, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Offermanns S. G-proteins as transducers in transmembrane signalling. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 83: 101–130, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pedersen EB, Danielsen H, Jensen T, Madsen M, Sorensen SS, Thomsen OO. Angiotensin II, aldosterone and arginine vasopressin in plasma in congestive heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest 16: 56–60, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Porter KE, Turner NA. Cardiac fibroblasts: at the heart of myocardial remodeling. Pharmacol Ther 123: 255–278, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Powell DW, Mifflin RC, Valentich JD, Crowe SE, Saada JI, West AB. Myofibroblasts. I. Paracrine cells important in health and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 277: C1–C9, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Riddle EL, Schwartzman RA, Bond M, Insel PA. Multi-tasking RGS proteins in the heart: the next therapeutic target? Circ Res 96: 401–411, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ross EM, Wilkie TM. GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 69: 795–827, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Scheschonka A, Dessauer CW, Sinnarajah S, Chidiac P, Shi CS, Kehrl JH. RGS3 is a GTPase-activating protein for Giα and Gqα and a potent inhibitor of signaling by GTPase-deficient forms of Gqα and G11α. Mol Pharmacol 58: 719–728, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sjogren B, Blazer LL, Neubig RR. Regulators of G protein signaling proteins as targets for drug discovery. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 91: 81–119, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Song L, De Sarno P, Jope RS. Muscarinic receptor stimulation increases regulators of G-protein signaling 2 mRNA levels through a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 274: 29689–29693, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Souders CA, Bowers SL, Baudino TA. Cardiac fibroblast: the renaissance cell. Circ Res 105: 1164–1176, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sun Y, Weber KT. Animal models of cardiac fibrosis. Methods Mol Med 117: 273–290, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suo M, Hautala N, Foldes G, Szokodi I, Toth M, Leskinen H, Uusimaa P, Vuolteenaho O, Nemer M, Ruskoaho H. Posttranscriptional control of BNP gene expression in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension 39: 803–808, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Swynghedauw B. Molecular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. Physiol Rev 79: 215–262, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Takimoto E, Koitabashi N, Hsu S, Ketner EA, Zhang M, Nagayama T, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, Blanton R, Siderovski DP, Mendelsohn ME, Kass DA. Regulator of G protein signaling 2 mediates cardiac compensation to pressure overload and antihypertrophic effects of PDE5 inhibition in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 408–420, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tang M, Wang G, Lu P, Karas RH, Aronovitz M, Heximer SP, Kaltenbronn KM, Blumer KJ, Siderovski DP, Zhu Y, Mendelsohn ME. Regulator of G-protein signaling-2 mediates vascular smooth muscle relaxation and blood pressure. Nat Med 9: 1506–1512, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tesmer JJ, Berman DM, Gilman AG, Sprang SR. Structure of RGS4 bound to AlF4−-activated Giα1: stabilization of the transition state for GTP hydrolysis. Cell 89: 251–261, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 349–363, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tsang S, Woo AY, Zhu W, Xiao RP. Deregulation of RGS2 in cardiovascular diseases. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2: 547–557, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. van Amerongen MJ, Bou-Gharios G, Popa E, van Ark J, Petersen AH, van Dam GM, van Luyn MJ, Harmsen MC. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute functionally to scar formation after myocardial infarction. J Pathol 214: 377–386, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Villarreal FJ, Kim NN, Ungab GD, Printz MP, Dillmann WH. Identification of functional angiotensin II receptors on rat cardiac fibroblasts. Circulation 88: 2849–2861, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Weber KT. Aldosterone in congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 345: 1689–1697, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Weber KT, Sun Y, Katwa LC. Myofibroblasts and local angiotensin II in rat cardiac tissue repair. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 29: 31–42, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Willems IE, Havenith MG, De Mey JG, Daemen MJ. The α-smooth muscle actin-positive cells in healing human myocardial scars. Am J Pathol 145: 868–875, 1994 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yano T, Miura T, Ikeda Y, Matsuda E, Saito K, Miki T, Kobayashi H, Nishino Y, Ohtani S, Shimamoto K. Intracardiac fibroblasts, but not bone marrow derived cells, are the origin of myofibroblasts in myocardial infarct repair. Cardiovasc Pathol 14: 241–246, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zak R. Development and proliferative capacity of cardiac muscle cells. Circ Res 35, Suppl II: 17–26, 1974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zeisberg EM, Kalluri R. Origins of cardiac fibroblasts. Circ Res 107: 1304–1312, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, Chandraker A, Yuan X, Pu WT, Roberts AB, Neilson EG, Sayegh MH, Izumo S, Kalluri R. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med 13: 952–961, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhang W, Anger T, Su J, Hao J, Xu X, Zhu M, Gach A, Cui L, Liao R, Mende U. Selective loss of fine tuning of Gq/11 signaling by RGS2 protein exacerbates cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem 281: 5811–5820, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zheng B, De Vries L, Gist Farquhar M. Divergence of RGS proteins: evidence for the existence of six mammalian RGS subfamilies. Trends Biochem Sci 24: 411–414, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zou MX, Roy AA, Zhao Q, Kirshenbaum LA, Karmazyn M, Chidiac P. RGS2 is upregulated by and attenuates the hypertrophic effect of α1-adrenergic activation in cultured ventricular myocytes. Cell Signal 18: 1655–1663, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.