Abstract

A wide variety of therapeutic agents may benefit by specifically directing them to the mitochondria in tumor cells. The current work aimed to design delivery systems that would enable a combination of tumor and mitochondrial targeting for such therapeutic entities. To this end, novel HPMA copolymer-based delivery systems that employ triphenylphosphonium (TPP) ions as mitochondriotropic agents were developed. Constructs were initially synthesized with fluorescent labels substituting for drug and were used for validation experiments. Microinjection and incubation experiments performed using these fluorescently labeled constructs confirmed the mitochondrial targeting ability. Subsequently, HPMA copolymer–drug conjugates were synthesized using a photosensitizer mesochlorin e6 (Mce6). Mitochondrial targeting of HPMA copolymer-bound Mce6 enhanced cytotoxicity as compared to nontargeted HPMA copolymer–Mce6 conjugates. Minor modifications may be required to adapt the current design and allow for tumor site-specific mitochondrial targeting of other therapeutic agents.

Keywords: Tumor targeting, mitochondrial targeting, HPMA copolymer, TPP, mesochlorin e6

Introduction

The attachment of low molecular weight anticancer drugs to water-soluble polymers serves as a facile technique to improve tumor tissue specificity due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.1 Macromolecular drug conjugates passively localize in tumor tissue as a result of the leaky neovasculature and blocked lymphatics and may result in a focused therapeutic effect. Active targeting by the attachment of tissue-specific moieties may help to further the specificity and reduce side effects.2 Polymeric carriers also serve to extend the circulation half-lives, increase solubility and may afford the ability to overcome certain cases of multidrug resistance.3,4

Typically, polymer–drug conjugates are internalized in tumor cells by endocytosis and localize in the lysosomal compartment. This property can be exploited to design polymer–drug conjugates containing specific degradable linker sequences to allow for the release of free drug and increase therapeutic efficacy. Linker sequences used in this regard include acid-sensitive linkers5,6 (sensitive to the low pH encountered in the lysosome), enzyme-sensitive linkers7 (sensitive to intra- or extracellular enzymes in tumor tissue) and disulfide bonds8 (susceptible to reductive conditions and/or enzymatic processes). We have previously developed and evaluated the efficacy of polymer–drug conjugates based on the N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) co-polymer backbone incorporating disulfide (SS)9 and cathepsin B sensitive glycylphenylalanylleucylglycyl10 (GFLG) linker sequences.

It may be desirable to manipulate the subcellular fate of the free drug following its release from the polymer backbone. Since drugs modulate metabolic pathways at specific subcellular sites, directing them to these sites may serve to enhance therapeutic efficacy. In this respect, the mitochondrion represents an important target due to its involvement in numerous metabolic pathways. In particular, the role of mitochondria in cancer has been a focus of intense research. Cancer cells exhibit alterations in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway, while mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations may play a role in oncogenesis.11,12 Mitochondria also play a central role in the regulation of apoptotic cell death. Apoptosis involves the release of proapoptotic proteins13,14 from the intermembrane space of the mitochondria into the cytosol. The triggering event, mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (MMP), may be induced by members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins. Alternatively, the opening of the permeability transition pore (PTP) may also elicit MMP. Released effector molecules, including cytochrome C, Smac/DIABLO, Omi/HtrA2, endonuclease G (Endo G) and apoptosis inducing factor (AIF), initiate a series of biochemical events that culminate in apoptotic cell death.

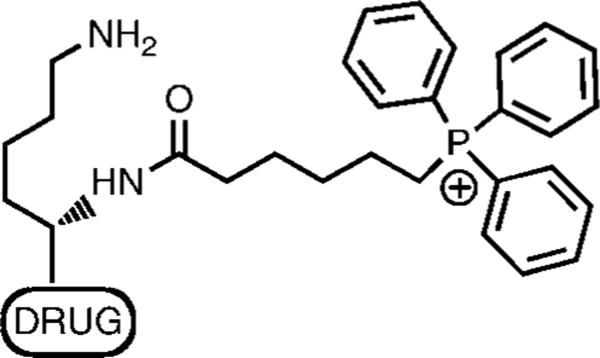

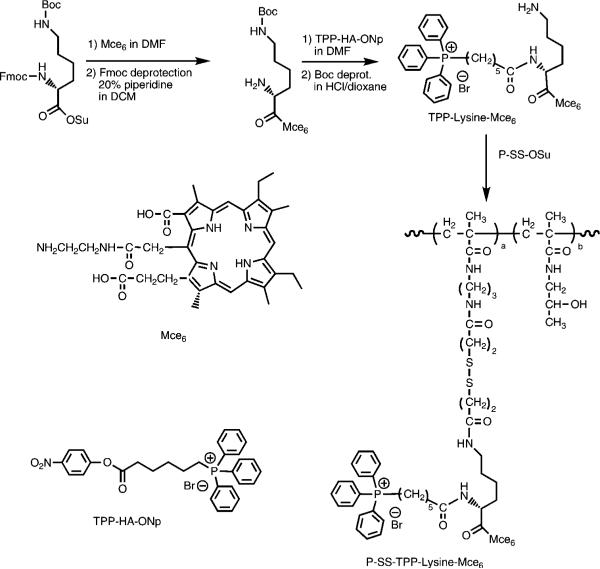

Given the importance of mitochondria in the evolution, progression and treatment of cancer, we sought to extend our previous work by developing HPMA copolymer-based delivery systems for combined mitochondrial and tumor targeting. The use of the HPMA copolymer backbone would allow for passive tumor targeting, while mitochondrial targeting was achieved by exploiting the negative mitochondrial transmembrane potential that develops as a result of oxidative phosphorylation.15 Prior research from our group has evaluated the feasibility of using triphenylphosphonium (TPP) ions as mitochondrial targeting agents for semitelechelic HPMA copolymers.16 In vitro incubation studies with low molecular weight (<5 kDa) TPP-targeted semitelechelic HPMA copolymers labeled with fluorophore BODIPY (4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene) demonstrated significant mitochondrial uptake.16 We present here a modified strategy to target the mitochondria in cancer cells by designing a HPMA copolymer-bound conjugate that incorporates lysine as a linker (Figure 1) to connect TPP and drug. The TPP–lysine–drug construct was subsequently attached to the HPMA copolymer backbone via a degradable disulfide bond. The strategy is expected to combine tumor targeting due to incorporation in HPMA copolymer-based drug delivery systems, with degradation of the disulfide bond on internalization and subsequent release and mitochondrial targeting of the TPP–lysine–drug construct. Initial concept validation was performed using the fluorophore BODIPY. Subsequently, constructs incorporating the photosensitizer mesochlorin e6 (Mce6) were developed and evaluated for cytotoxic efficacy. The use of a photosensitizer as the therapeutic payload was predicated on the high sensitivity of mitochondria to photodynamic damage.17

Figure 1.

Construct design for mitochondrial targeting.

Experimental Section

Cell Line

The human ovarian cancer cell line NIH: SKOV-3 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 (v/v) in air at 37 °C. Experiments were performed during log phase of cell growth.

Materials

The photosensitizer mesochlorin e6 monoethylenediamine (Mce6) was obtained from Frontier Scientific, Logan, UT. The fluorophore 4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-propionyl ethylenediamine, hydrochloride (BODIPY FL EDA) was obtained from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, and were of HPLC grade or better.

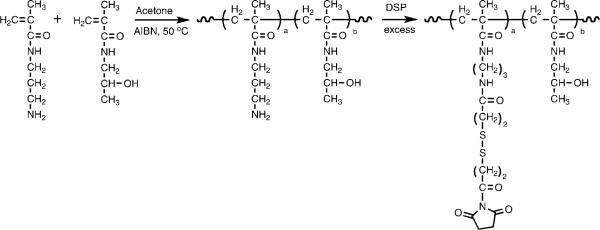

Synthesis of HPMA Polymer Precursor Containing Disulfide Bonds

HPMA polymer precursor containing disulfide bonds (P-SS-OSu) was synthesized using the procedure described previously (Figure 2).9 Briefly, a polymer containing 3-aminopropyl side chains was prepared by radical copolymerization of HPMA with N-(3-aminopropyl)methacrylamide using 2,2′-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) as the initiator and 3-mercaptopropionic acid as the chain transfer agent (molar ratio 90/10/4/0.4). The content of pendant amine groups determined using a ninhydrin assay was 0.55 mmol/g (7.9 mol %). The polymer was then activated with a 6-fold molar excess of dithiobis(succinimidyl)propionate (DSP) and purified by precipitation in an excess of acetone:diethyl ether followed by fractionation on Sephadex LH-20 in methanol with 0.5% acetic acid. The content of −OSu groups determined by UV spectrophotometry after aminolysis of released −OSu (anion) [UV (methanol): λmax (ε) = 260 nm (8500 L · mol−1 · cm−1)] was 0.33 mmol/g (4.9 mol %). The molecular weight determined by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) using the ÄKTA FPLC system (Pharmacia) on Superose 6 HR 10/30 columns (PBS + 30% acetonitrile) calibrated with HPMA copolymer fractions was 48 kDa with a polydispersity of 1.6.

Figure 2.

Synthetic scheme for polymer precursor containing disulfide bonds (P-SS-OSu).

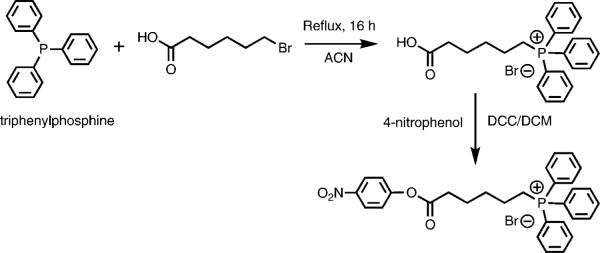

Synthesis of (5-Carboxypentyl)triphenylphosphonium Bromide 4-Nitrophenyl Ester

Synthesis of (5-carboxypentyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide was achieved by coupling triphenylphosphine (TPP) and 6-bromohexanoic acid (Figure 3).18 Briefly, 973 mg of TPP (5 × 10−3 mol) was refluxed with 1377 mg of 6-bromohexanoic acid (5.25 × 10−3 mol) in 5 mL of dry acetonitrile under nitrogen for 16 h. After cooling to room temperature, 1700 mg (yield 90%) of the product was obtained by crystallization. Product was confirmed by TLC (thin layer chromatography), ESI-MS [electrospray ionization mass spectrometry: m/z = 377.2 (M + 1)], melting point analysis19 (195–197 °C) and HPLC (high performance liquid chromatography) analysis (90% pure) performed on an Agilent 1100 series HPLC apparatus equipped with a diode array detector using a gradient method using a mixture of distilled water with 0.1% TFA (buffer A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA (buffer B) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Analysis was performed twice, the first time using a C18 column (Zorbax 300SB-C18 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm) and the second time using an acrylamide column (Supelcosil ABZ+ Plus 4.6 × 50 mm, 3 μm). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ7.79–7.66 (m, 15H, Ar–H), δ3.63–3.56 (m, 2H, CH2), δ2.36–2.33 (m, 2H, CH2), δ1.64 (s, 6H, CH2).

Figure 3.

Synthetic scheme for (5-carboxypentyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide 4-nitrophenyl ester (TPP-HA-ONp).

Synthesized (5-carboxypentyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide was activated with 4-nitrophenol using dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) coupling in dichloromethane (DCM). Briefly, 113 mg of (5-carboxypentyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (3 × 10−4 mol) and 50 mg of 4-nitrophenol (3.6 × 10−4 mol) were mixed together in 10 mL of DCM. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and a solution of 74.27 mg of DCC (3.6 × 10−4 mol) in 5 mL of DCM was added dropwise. The reaction was stopped the next day, and dicyclohexylurea crystals were filtered out. The product, (5-carboxypentyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide 4-nitrophenyl ester (TPP-HA-ONp), was purified by precipitation in excess of ether. Yield was 105 mg (70%). Purity was confirmed by TLC and HPLC analysis (90% pure). Product identity was confirmed by MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight) mass spectrometry analysis: m/z) = 498.2 (M + 1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ8.24–8.22 (m, 2H, Ar–H), δ7.77–7.60 (m, 15H, Ar–H), δ7.23–7.22 (m, 2H, Ar–H), δ3.50–3.40 (m, 2H, CH2), δ2.61–2.58 (t, 2H, CH2), δ1.70 (s, 6H, CH2).

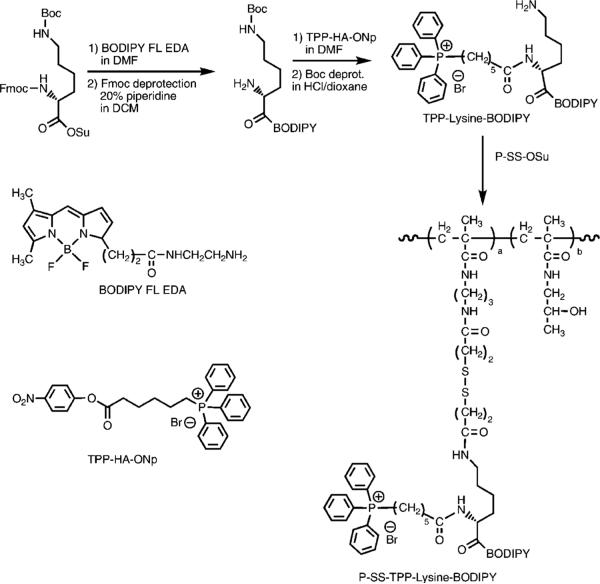

Synthesis of P-SS-TPP–Lysine–BODIPY

The synthetic scheme employed is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Synthetic scheme for P-SS-TPP–lysine–BODIPY.

The Nε-Boc-lysine-BODIPY intermediate (lysine-BODIPY) was synthesized by the reaction of Nα-Fmoc, Nε-Boc-lysine N-hydroxysuccinimide ester with BODIPY FL EDA in dimethylformamide (DMF) followed by deprotection of the α-NH2 group using 20% piperidine in DCM. Briefly, 4 mg of BODIPY FL EDA (1.1 × 10−5 mol) was reacted with 12.2 mg of Nα-Fmoc, Nε-Boc-lysine N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (2.2 × 10−5 mol) in 1 mL of DMF for 24 h. The product was purified by Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography in methanol following which the Fmoc protecting group was removed using 20% piperidine in DCM for 30 min. Yield was 3.1 mg (50%). Product purity and identity were confirmed by TLC, HPLC analysis (95% pure) and MALDI-TOF analysis: m/z = 563.3 (M + 1).

The synthesized lysine-BODIPY intermediate was reacted with TPP-HA-ONp in DMF followed by deprotection of the ε-NH2 group using HCl in dioxane for 30 min. The reaction was performed with 2.8 mg of lysine-BODIPY (5 × 10−6 mol) and 8.64 mg of activated TPP-HA-ONp (15 × 10−6 mol) in the presence of 0.6 mg of DMAP (5 × 10−6 mol) in 0.5 mL of DMF. The reaction mixture was purified on Sephadex LH-20 in methanol following which the Boc group was removed using HCl in dioxane for 30 min. The product Nα-TPP–lysine–BODIPY (TPP–lysine–BODIPY) was then purified using the Agilent 1100 series HPLC apparatus equipped with a reverse-phase C18 column (Zorbax 300SBCN 9.4 × 250 mm, 5 μm) and a variable wavelength detector. A gradient method using a mixture of distilled water with 0.1% TFA (buffer A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA (buffer B) at a flow rate of 2.5 mL/min was used for the purification. Yield was 3.7 mg (90%). Product was confirmed using HPLC and MALDI-TOF analysis: m/z = 821.5 (M + 1).

A solution of 3.4 mg of TPP–lysine–BODIPY (4.2 × 10−6 mol) in 0.5 mL of DMF was then added dropwise to a solution of 12.7 mg of P-SS-OSu (4.2 × 10−6 mol of OSu) in 1 mL of DMF in the presence of 0.5 mg of DMAP (4.2 × 10−6 mol). The next day, residual −OSu groups were inactivated using an excess of 1-amino-2-propanol and the polymer was purified on Sephadex LH-20 in methanol with 0.5% acetic acid. The BODIPY content measured using UV spectrophotometry in methanol [UV (methanol): λmax (ε) = 503 nm (76000 L · mol−1 · cm−1)] was 2.0 × 10−4 mol/g (3.7 mol %).

Synthesis of P-SS-TPP–Lysine–Mce6

The synthetic scheme employed is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Synthetic scheme for P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6.

The Nε-Boc-lysine-Mce6 (lysine-Mce6) intermediate was synthesized by the reaction of Nα-Fmoc,Nε-Boc-lysine N-hydroxysuccinimide ester with Mce6 in DMF followed by deprotection of the α-NH2 group using 20% piperidine in DMF. Briefly, 113 mg of Nα-Fmoc, Nε-Boc-lysine N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (2 × 10−4 mol) was reacted with 68.4 mg of Mce6 (1 × 10−4 mol) in 3 mL of DMF for 24 h. The reaction mixture was taken to dryness and purified using Sephadex LH-20 in methanol. The Fmoc protecting group on α-NH2 was removed using 20% piperidine in DMF and purified using silica gel chromatography. Yield was 70 mg (80%). Product purity and identity were confirmed by TLC, HPLC analysis (90% pure) and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis: m/z = 869.4 (M + 1).

The lysine-Mce6 intermediate was then treated with TPPHA-ONp followed by deprotection of the Nε-Boc group using 50% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in dichloromethane. The reaction was performed with 64.8 mg of lysine-Mce6 (7.5 × 10−5 mol) and 132.6 mg of activated TPP-HA-ONp (22.4 × 10−5 mol) in the presence of 9.1 mg of DMAP (7.5 × 10−5 mol) in 2 mL of DMF. The reaction mixture was purified on Sephadex LH-20 in methanol following which the Boc group was removed using 50% TFA in DCM for 30 min. The product Nα-TPP–lysine–Mce6 (TPP–lysine–Mce6) was then purified by reverse-phase preparative HPLC purification using a gradient method. A mixture of distilled water with 0.1% TFA (buffer A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA (buffer B) at a flow rate of 2.5 mL/min was used for the purification. Yield was 60 mg (71%). Product was confirmed using HPLC and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis: m/z = 1127.6 (M + 1).

A solution of 18.5 mg of TPP–lysine–Mce6 (1.65 × 10–5 mol) in 0.5 mL of DMF was then added dropwise to a solution of 50 mg of P-SS-OSu (1.65 × 10−5 mol OSu) in 2 mL of DMF in the presence of 2.8 μL×of diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA). The next day, the polymer was purified by Sephadex G-25 column chromatography, followed by dialysis and freeze-drying. Yield was 55 mg. Molecular weight determined using SEC was 71 kDa with a polydispersity of 2.1. The Mce6 content measured using UV spectrophotometry [UV (methanol): λmax (ε) = 395 nm (158000 L · mol−1 · cm−1)] was 1.9 × 10−4 mol/g (3.7 mol %).

Synthesis of Control Polymers

Control polymer P-SS–Mce6 was synthesized according to the procedure detailed previously.9 Molecular weight determined using SEC was 35 kDa with a polydispersity of 1.6. The Mce6 content measured using UV spectrophotometry in methanol was 2.3 × 10−4 mol/g (4.0 mol %).

Microinjection of TPP–Lysine–BODIPY in SKOV-3 Cells

SKOV-3 cells were plated at a density of 100,000 cells/well in 0.17 mm Delta T temperature-controlled microwell dishes (Bioptechs, Butler, PA). The next day, the cells were labeled using a 500 nM solution of Mitotracker Orange CM-H2TMROS for 30 min. A solution of TPP–lysine–BODIPY was microinjected in the cytosol of SKOV-3 cells using 0.5 μm glass needles on an Eppendorf Transjector 5346 pressure injector fixed to an Eppendorf 5171 micromanipulator arm. Injection pressures varied from 50 to 100 hPa. The medium was replaced immediately after microinjection, and the cells were observed using an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 scanning laser confocal microscope to determine subcellular localization of the BODIPY-labeled constructs.

Incubation of TPP–Lysine–BODIPY and P-SS-TPP–Lysine–BODIPY with SKOV-3 Cells

SKOV-3 cells were plated at a density of 100,000 cells/dish in Bioptechs Delta T dishes. The next day, mitochondria were labeled with a 500 nM solution of Mitotracker Orange CM-H2TMROS for 30 min. The cells were washed twice with PBS and replaced with fresh medium containing 5 μM TPP–lysine–BODIPY or 20 μM P-SS-TPP–lysine–BODIPY for varying durations at 37 °C. The cells were visualized periodically using an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 scanning laser confocal microscope to determine subcellular localization of the BODIPY-labeled constructs.

Comparison of Cytotoxicity of P-SS–Mce6 and P-SS-TPP–Lysine–Mce6

The IC50 doses were determined utilizing a 2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium monosodium salt (CCK-8) (Dojindo) bioassay. Briefly, SKOV-3 cells were seeded in 96 well plates at a density of 10,000 cells/well. The next day, cells were incubated with serial dilutions (Mce6 concentration) of P-SS–Mce6 and P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 in media. After specified durations, the cells were washed with PBS and replaced with fresh cell culture medium and irradiated using a lamp assembly for 30 min. The lamp assembly consisted of 3 ENH tungsten halogen projector lamps (120 V/250 W each). The light from these lamps was filtered using 650 nm red acetate band-pass filters to produce red light to excite Mce6. Cell viability was determined 24 h after irradiation using the CCK-8 bioassay according to the directions of the manufacturer. The percentage of cells surviving was calculated by dividing the mean absorbance of treated cells by the mean absorbance of CCK-8 control. Control cells were considered as 100% viable. Dose–response curves were constructed and the IC50 was determined.

Results

The HPMA copolymer-bound TPP-targeted constructs were designed to combine passive tumor targeting, afforded by incorporation into HPMA copolymer-based polymeric delivery systems with mitochondrial targeting using triphenylphosphonium (TPP) ions. The ability of TPP to induce mitochondrial translocation was evaluated by confocal microscopic evaluation of microinjection and incubation experiments of BODIPY-tagged fluorescent constructs.

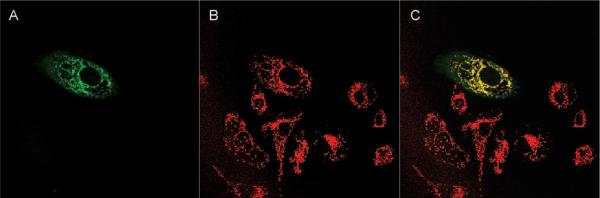

TPP–Lysine–BODIPY Translocates to the Mitochondria Following Introduction into the Cytoplasm

A solution of TPP–lysine–BODIPY was microinjected in the cytoplasm of ovarian carcinoma SKOV-3 cells, and the subcellular localization was followed by confocal microscopy. Typical results from microinjected cells with TPP–lysine–BODIPY are shown in Figure 6. The BODIPY fluorescence of the TPP-targeted constructs colocalizes with the fluorescence of Mitotracker Orange (red channel), indicating the mitochondrial localization of TPP–lysine–BODIPY. Minimal BODIPY fluorescence was observed in the cytoplasm. Images were taken immediately after microinjection and indicate the rapid uptake of the constructs in the mitochondria. In contrast, cells microinjected with BODIPY did not show any distinct pattern of subcellular distribution (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Microinjection of TPP–lysine–BODIPY in SKOV-3 cells. In these images, the first field (A) shows the fluorescence due to BODIPY and therefore indicates the subcellular location of TPP–lysine–BODIPY. The second field (B) indicates the fluorescence due to Mitotracker and indicates the intracellular localization of the mitochondria. The third field (C) is the combined image of fields A and B.

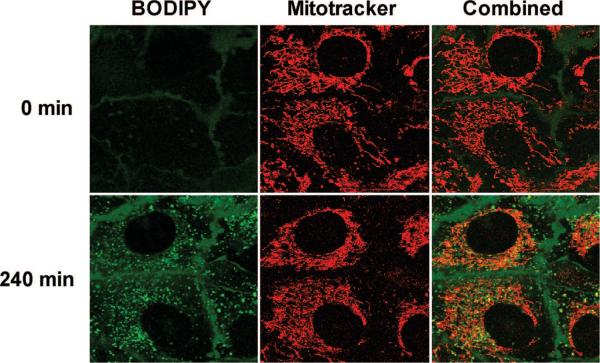

TPP Induces Mitochondrial Translocation of Both TPP–Lysine–BODIPY and P-SS-TPP–Lysine–BODIPY Following Incubation with SKOV-3 Cells

Ovarian carcinoma SKOV-3 cells labeled with Mitotracker Orange were incubated with 5 μM free TPP–lysine–BODIPY, and the subcellular distribution was followed every 15 min using confocal microscopy for 4 h. Results from representative cells at 2 different time points are shown in Figure 7. The fluorescence of BODIPY initially showed a punctate distribution, which was accompanied at later time points by a mitochondrial distribution, confirmed by colocalization with Mitotracker. The intensity of BODIPY in the mitochondria exhibited a time-dependent increase, indicating a gradual uptake of TPP–lysine–BODIPY in the mitochondria. The intensity of BODIPY fluorescence in the mitochondria increased gradually with time as indicated by image analysis performed using proprietary software developed at the University of Utah School of Medicine Cell Imaging Facility (results not shown).

Figure 7.

Incubation of SKOV-3 cells with TPP–lysine–BODIPY. SKOV-3 cells were initially labeled with Mitotracker Orange and then incubated with 5 μM TPP–lysine–BODIPY. Subcellular fate of TPP–lysine–BODIPY constructs was followed every 15 min for 4 h. In these images, the first field (marked BODIPY) shows the fluorescence due to BODIPY and therefore indicates the subcellular location of TPP–lysine–BODIPY. The second field (marked Mitotracker) indicates the fluorescence due to Mitotracker and indicates the intracellular localization of the mitochondria. The third field (marked Combined) is the combined image of the two fields.

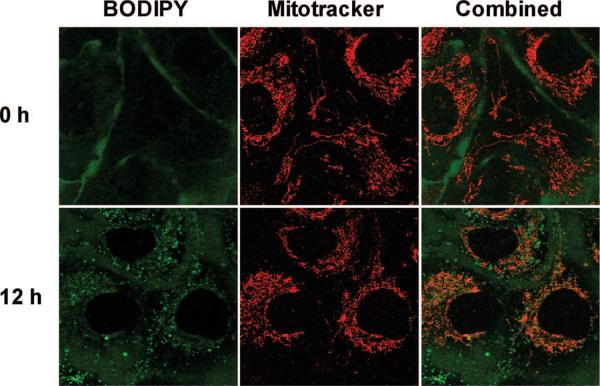

Next, a 20 μM solution of P-SS-TPP–lysine–BODIPY was incubated with SKOV-3 cells labeled with Mitotracker Orange. Results from representative cells at 2 different time points are shown in Figure 8. As in the case of TPP–lysine–BODIPY, an initial punctuate distribution of BODIPY fluorescence was accompanied with a time-dependent increase in BODIPY fluorescence intensity in the mitochondria. Quantitative analysis confirmed this gradual increase in the BODIPY fluorescence intensity in the mitochondria (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Incubation of SKOV-3 cells with P-SS-TPP–lysine–BODIPY. SKOV-3 cells were initially labeled with Mitotracker Orange and then incubated with 20 μM P-SS-TPP–lysine–BODIPY. Subcellular fate of TPP–lysine–BODIPY constructs was followed every 60 min for 12 h. In these images, the first field (marked BODIPY) shows the fluorescence due to BODIPY and therefore indicates the subcellular location of TPP–lysine–BODIPY. The second field (marked Mitotracker) indicates the fluorescence due to Mitotracker and indicates the intracellular localization of the mitochondria. The third field (marked Combined) is the combined image of the two fields.

Synthesis and Characterization of TPP-Targeted Mesochlorin e6 Containing Constructs

Concept validation studies with BODIPY were followed by the synthesis of cytotoxic constructs containing the photosensitizer mesochlorin e6 as the therapeutic payload. As photosensitizers demonstrate enhanced sensitivity in the mitochondria,17 such an approach is expected to increase the efficacy of Mce6. Properties of the synthesized mitochondrial-targeted HPMA copolymer–Mce6 (P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6) and control P-SS–Mce6 conjugates are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characterization of P-SS–Mce6 and P-SS-TPP–Lysine–Mce6

| Mce6 content |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| polymer | Mw (kDa)a | polydispersitya | (mol/g)b ( | (mol %)b |

| P-SS–Mce6 | 35 | 1.6 | 2.3 × 10−4 | 4.0 |

| P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 | 71 | 2.1 | 1.9 × 10−4 | 3.7 |

Molecular weight determined by SEC using the ÄKTA FPLC system (Pharmacia) on Superose 6 HR 10/30 columns (PBS + 30% acetonitrile) calibrated with HPMA copolymer fractions.

Mce6 content determined by UV spectrophotometry in methanol [UV (methanol): λmax (∊) = 395 nm (158000 L · mol−1 ·cm1)].

Mitochondrial Targeting Using TPP Increases the Cytotoxicity of HPMA Copolymer-Bound Mce6

Synthesized conjugates were tested for cytotoxic efficacy in the SKOV-3 ovarian carcinoma cell line. No dark toxicity for the mitochondrial-targeted constructs was observed. The IC50 values for the TPP-targeted HPMA copolymer-bound Mce6 as compared to nontargeted HPMA copolymer-bound Mce6 are shown in Table 2. These results indicate that mitochondrial targeting of HPMA copolymer-bound Mce6 using TPP improves the efficacy as compared to nontargeted HPMA copolymer-bound Mce6. A time dependent increase in cytotoxicity was also observed in the case of both P-SS–Mce6 and P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6. However, the IC50 values seemed to plateau after about 4 h in the case of P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6. A similar plateau seemed to occur after 8 h in the case of P-SS–Mce6.

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity of P-SS–Mce6 and P-SS-TPP–Lysine–Mce6 in SKOV-3 Cells for Different Times of Incubationa

| IC50 (μM) (mean ± SD) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 2 h | 4 h | 8 h | 12 h | |

| P-SS–Mce6 | 81.10 ± 2.12 | 38.71 ± 1.38 | 19.97 ± 1.51 | 9.31 ± 0.27 | 7.69 ± 0.48 |

| P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 | 40.63 ± 2.68 | 18.64 ± 0.55 | 10.74 ± 0.19 | 8.54 ± 0.12 | 5.36 ± 0.48 |

IC50 determined by incubating serial dilutions (Mce6 concentration) of polymer–drug conjugates with SKOV-3 cells for specified periods of time. Illumination achieved using a lamp assembly for 30 min. Viability determined by CCK-8 bioassay and used to construct dose–response curves and determine IC50. Values expressed as mean IC50 values with standard deviations (SD) calculated from 3–4 replicates in each case.

Discussion

The importance of mitochondria in tumor biology was first reported by Otto Warburg, who proposed that injury to the respiratory machinery may result in compensatory increases in glycolytic ATP production20 (a phenomenon often referred to as “aerobic glycolysis”), dedifferentiation of cells and consequent neoplastic transformation. Alterations in the oxidative phosphorylation may in turn increase mitochondrial ROS production, causing nuclear mutagenesis of proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressors, thereby acting as tumor initiators.11,21 Tumor promotion via enhancement of nuclear replication may also play a role.11 The transition to aerobic glycolysis may confer a survival advantage by enabling tumor cells to adapt to hypoxic conditions.22 The acidification of the tumor microenvironment due to increased glycolysis may also promote extracellular matrix degradation and subsequent tumor metastasis.22 Mutations in mtDNA have been observed in cancers of the breast,23 ovarian,24 colorectal,25kidneys26 and thyroid carcinoma,27 to name a few. It is possible that some of these mtDNA mutations may be the result of damage due to endogenous ROS in cancer cells. The prominent role played by mitochondrial factors in the apoptotic pathway13,14 further underscores the therapeutic benefit that may be afforded by selectively targeting the mitochondria in tumor tissue. The initiation of apoptosis using Bcl-2 inhibitors,28,29 proapoptotic Bcl-2 factors,30,31or inducers of PTP32 may represent a viable strategy for effective anticancer therapy. Conventional anticancer therapeutics, like paclitaxel33,34 and cisplatin,35 also act on mitochondria triggering apoptosis. In addition, agents designed to disrupt the redox balance36 or damage mtDNA37 may prove useful as anticancer therapeutics.

The importance of mitochondria in tumorigenesis and anticancer therapy brings into focus the therapeutic benefit that may be afforded by targeting specific therapeutic agents to the mitochondria of tumor cells. Such an approach may allow for the modulation of specific subcellular biochemical pathways and help reduce side effects. Mitochondrial targeting in cancer can be achieved by using various mitochondriotropic agents as carriers. These have commonly included the use of signal sequences involved in the mitochondrial import pathways, cationic lipids and delocalized lipophilic cations. Endogenous mitochondrial import pathways38 for the transport of proteins, lipids and nucleic acids use distinct import signal sequences to induce mitochondrial uptake. This machinery can be exploited for mitochondrial targeting by attachment of these signal sequences to target molecules, for example, proteins,39 oligonucleotides40,41 and peptide nucleic acids.42 Mitochondriotropic lipid vesicles have also been demonstrated to effectively deliver cargo to the mitochondria.43 Alternatively, delocalized lipophilic cations (DLCs) can be used to achieve mitochondrial targeting by exploiting the negative mitochondrial trans-membrane potential of up to 180 mV.15 The triphenylphosphonium (TPP) ion has been extensively used by Murphy and his colleagues to target therapeutics44,45 to the mitochondria.

In the case of anticancer therapeutics, it is also essential to confer an element of tissue specificity to reduce toxicity in normal tissues. Impaired oxidative phosphorylation activity and inhibition of ATP synthase activity in tumor cells may result in a higher transmembrane potential gradient37 as compared to normal cells and confer some tumor tissue specificity. However, it can be expected that normal tissues would also accumulate DLCs and the attached biomolecules of interest, resulting in unwanted side effects. A more salient method to achieve effective tumor targeting involves incorporation of the therapeutic entity in polymeric delivery systems, which allow for localizing in tumor tissue by the EPR effect.1 Other advantages may also be conferred using this approach.3,4

To achieve a combination of tumor targeting and mitochondrial targeting for anticancer drugs, the design of the construct incorporated lysine to combine the three components: drug, TPP and the polymer backbone. The drug was attached to the carboxyl group of lysine while the TPP ion was attached to the α-NH2 end. The TPP–drug complexes were subsequently attached to the HPMA copolymer backbone via a disulfide bond via the ε-NH2 group of lysine. These water-soluble polymer–drug conjugates were expected to internalize by endocytosis and localize in the endosomal compartment. The incorporated disulfide bond was selected to achieve rapid degradation in the endosomal environment and allow for the release of the TPP–drug construct.9 The construct free from the polymer backbone could then target the mitochondria, thus allowing for mitochondrial-targeted therapy in cancer.

Initially, the polymer–drug conjugates were synthesized using a BODIPY label to evaluate the subcellular distribution and mitochondrial targeting ability of the designed constructs. Synthesis of the TPP–lysine–BODIPY construct and P-SS-TPP–lysine–BODIPY was achieved using the synthetic scheme outlined in Figure 4. First, the ability of TPP–lysine–drug constructs to translocate from the cytoplasm of ovarian carcinoma SKOV-3 cells into the mitochondria was evaluated. This was done by determining the subcellular distribution of TPP–lysine–BODIPY following microinjection. As observed in Figure 6, the fluorescence from BODIPY colocalized with the fluorescence due to Mitotracker, indicating that TPP–lysine–BODIPY was present in the mitochondria.

Next, SKOV-3 cells incubated with a 5 μM solution of TPP–lysine–BODIPY demonstrated a time-dependent trans-location into the mitochondria (Figure 7), which was confirmed by quantification software. These results indicate that free TPP-targeted constructs were able to transport across biological membranes to achieve mitochondrial uptake. A similar study was performed by incubating SKOV-3 cells with a 20 μM solution of P-SS-TPP–lysine–BODIPY. The study was designed to test disulfide bond cleavage, release of free TPP–drug constructs and subsequent mitochondrial translocation of TPP-targeted drug complexes. Results obtained demonstrated a time-dependent mitochondrial targeting (Figure 8), confirmed by quantification analysis. These experiments validated our design for the construct for targeting drugs using TPP as a mitochondriotropic carrier attached to the HPMA copolymer backbone via a disulfide bond.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a novel form of treatment for cancer that involves activation of photosensitizers by illumination with light of specific wavelengths. Activation induces the transition of photosensitizer molecules from the ground singlet state to a short-lived excited singlet state and subsequently to a longer-lived excited triplet state via intersystem crossing. The excess energy from these excited states of the photosensitizer is then transferred to molecular oxygen, leading to generation of singlet oxygen. The singlet oxygen in turn damages biomolecules, compromising biological structure and function. PDT has therefore been described as a three-component therapy46 that involves the interaction of photosensitizers, light and oxygen, where the photosensitizer serves to act as a conduit for the transfer of energy from light to molecular oxygen. Singlet oxygen has a very short half-life47 and induces photodynamic damage around its site of generation, which relates to the subcellular localization of photosensitizers. We have previously evaluated10,48 HPMA copolymer conjugates incorporating Mce6, a second generation photosensitizer, as a strategy to specifically target tumor cells and attempted to define the mechanisms of cell death induced by these conjugates.49

Directing photosensitizers to subcellular compartments susceptible to photodynamic damage can be employed as a strategy to increase therapeutic efficacy. Prior research has elucidated that the mitochondria represent a target that is very susceptible to photodynamic damage.17 Targeting the mitochondria with photosensitizers may induce cell death by the destruction of the mitochondrial PTP complex proteins and release of pro-apoptotic factors into the cytosol.50 The destruction of the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 may represent another mechanism.51 Photosensitizer targeting to the mitochondria can be achieved by use of pro-photosensitizer drugs either endogenously synthesized in the mitochondria, as in the case of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA).52 In addition, data obtained with photosensitizers targeting the mitochondria on account of their physicochemical properties have verified the benefits of inducing mitochondrial photo-damage.53–57 These studies provided the basis for incorporating Mce6 in the construct to utilize mitochondrial targeting as a strategy to improve photodynamic efficacy.

Synthesis of P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 was achieved using the synthetic scheme outlined in Figure 5. Characterization of P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 (Table 1) using SEC revealed minor cross-linking, with a consequent increase in the molecular weight and polydispersity. The weight-average molecular weight and polydispersity values for P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 were 71 kDa and 2.1, respectively. The corresponding values for the control polymer, P-SS–Mce6, were 35 kDa and 1.6. The minor variation in molecular weight and polydispersity is not expected to significantly alter the uptake and subsequent subcellular processing of the conjugates. Both P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 and control polymer P-SS–Mce6 showed relatively similar molar incorporation of Mce6 (4.0 mol % and 3.7 mol %, respectively).

The cytotoxicity of the P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 was compared to P-SS–Mce6 using serial drug dilutions and the measurement of cell viability using the CCK-8 bioassay. Both polymer conjugates did not demonstrate any dark toxicity. The IC50 values for these conjugates obtained at different time points are displayed in Table 2. Mitochondrial-targeted P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 conjugates were more cytotoxic as compared to nontargeted P-SS–Mce6 conjugates. Furthermore, both polymer conjugates showed a time dependent increase in cytotoxicity. The ratio of IC50 values for P-SS–Mce6 as compared to P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 at earlier time points was higher as compared to the similar ratio at later time points. For example, at 1 and 2 h, the IC50 values for P-SS–Mce6 were approximately twice that of P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6. However, for longer periods of incubation, the ratio of IC50 values for P-SS–Mce6 as compared to P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 decreases.

The decrease in the relative efficacy of mitochondrial targeting of Mce6 over time could be explained by the stabilization in the IC50 values for P-SS-TPP–lysine–Mce6 at longer periods of incubation. Over shorter periods of incubation, TPP ions may cause the active uptake of Mce6 in the mitochondria and result in a rapid decrease in IC50 values. Over longer periods of incubation, these IC50 values may plateau. In the case of P-SS–Mce6, free Mce6 may passively accumulate in various subcellular compartments following release from the HPMA copolymer backbone. Increasing amounts of photodynamic damage at these sites as a result of the higher concentrations of Mce6 over time may contribute to the decrease in IC50 values for the non-TPP targeted constructs over time. In fact, nontargeted Mce6 may induce photodynamic damage in the mitochondria. Previous research has indicated that porphyrin photosensitizers localize in the mitochondria.58 In this scenario, the attachment of TPP as a mitochondriotropic carrier may only serve to speed up mitochondrial uptake. Over longer incubation periods, the localization of nontargeted Mce6 in the mitochondria from P-SS–Mce6 would reduce the benefit of attaching TPP.

In retrospect, it may be worthwhile testing the construct with an agent that is specifically active, but does not naturally localize in the mitochondria. Small molecule inhibitors of the oncoprotein Bcl-2 may be extremely interesting in this regard. Incorporation of these agents in the current drug delivery system could be easily achieved and may present clinically relevant therapeutics for the specific targeting of mitochondria in tumor tissue. This strategy may circumvent conventional resistance to anticancer agents and overcome one of the impediments to efficacious anticancer therapy.29 Other applications of this research may come in the area of mitochondrial DNA diseases. Gene therapies directed toward mtDNA may benefit from the current delivery system that allows for relatively specific targeting of mitochondria. Targeted delivery of protective agents against free radicals may represent efficacious therapies for a wide variety of diseases caused by oxidative stress.

Acknowledgment

Images were obtained and processed at the University of Utah School of Medicine Cell Imaging Facility. We also thank Monika Sima for excellent technical assistance. This research was supported by the Department of Defense (Army) under Grant W81XWH-04-1-0900 and by the National Institutes of Health under Grant CA51578.

References

- (1).Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent SMANCS. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Allen TM. Ligand-targeted therapeutics in anticancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:750–763. doi: 10.1038/nrc903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Duncan R. The dawning era of polymer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2003;2:347–360. doi: 10.1038/nrd1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kopeček J, Kopečková P, Minko T, Lu Z. HPMA copolymeranticancer drug conjugates: design, activity, and mechanism of action. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2000;50:61–81. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Shen WC, Ryser HJ. cis-Aconityl spacer between daunomycin and macromolecular carriers: a model of pH-sensitive linkage releasing drug from a lysosomotropic conjugate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1981;102:1048–1054. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91644-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Willner D, Trail PA, Hofstead SJ, King HD, Lasch SJ, Braslawsky GR, Greenfield RS, Kaneko T, Firestone RA. (6-Maleimidocaproyl)hydrazone of doxorubicin-a new derivative for the preparation of immunoconjugates of doxorubicin. Bioconjugate Chem. 1993;4:521–527. doi: 10.1021/bc00024a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Rejmanová P, Kopeček J, Pohl J, Baudyš M, Kostka V. Polymers containing enzymically degradable bonds. 8. Degradation of oligopeptide sequences in N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymers by bovine spleen cathepsin B. Makromol. Chem. 1983;184:2009–2020. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Shen WC, Ryser HJ, LaManna L. Disulfide spacer between methotrexate and poly(D-lysine). A probe for exploring the reductive process in endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:10905–10908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cuchelkar V, Kopečková P, Kopeček J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of disulfide-linked HPMA copolymer-mesochlorin e6 conjugates. Macromol. Biosci. 2008;8:375–383. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200700240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Omelyanenko V, Gentry C, Kopečková P, Kopeček J. HPMA copolymer-anticancer drug-OV-TL16 antibody conjugates. II Processing in epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells in vitro. Int. J. Cancer. 1998;75:600–608. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980209)75:4<600::aid-ijc18>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wallace DC. Mitochondria and cancer: Warburg addressed. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 2005;70:363–374. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Alirol E, Martinou JC. Mitochondria and cancer: is there a morphological connection. Oncogene. 2006;25:4706–4716. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Patterson SD, Spahr CS, Daugas E, Susin SA, Irinopoulou T, Koehler C, Kroemer G. Mass spectrometric identification of proteins released from mitochondria undergoing permeability transition. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:137–144. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ravagnan L, Roumier T, Kroemer G. Mitochondria, the killer organelles and their weapons. J. Cell. Physiol. 2002;192:131–137. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Murphy MP. Selective targeting of bioactive compounds to mitochondria. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:326–330. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Callahan J, Kopeček J. Semitelechelic HPMA copolymers functionalized with triphenylphosphonium as drug carriers for membrane transduction and mitochondrial localization. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2347–2356. doi: 10.1021/bm060336m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Peng Q, Moan J, Nesland JM. Correlation of subcellular and intratumoral photosensitizer localization with ultrastructural features after photodynamic therapy. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 1996;20:109–129. doi: 10.3109/01913129609016306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Deroose FD, De Clercq PJ. Novel enantioselective syntheses of (+)-biotin. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:321–330. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kato K, Ohkawa S, Terao S, Terashita Z, Nishikawa K. Thromboxane synthetase inhibitors (TXSI). Design, synthesis, and evaluation of a novel series of omega-pyridylalkenoic acids. J. Med. Chem. 1985;28:287–294. doi: 10.1021/jm00381a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956;124:269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Behrend L, Henderson G, Zwacka RM. Reactive oxygen species in oncogenic transformation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31:1441–1444. doi: 10.1042/bst0311441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Gillies RJ, Gatenby RA. Hypoxia and adaptive landscapes in the evolution of carcinogenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:311–317. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9065-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Tan DJ, Bai RK, Wong LJ. Comprehensive scanning of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:972–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Liu VW, Shi HH, Cheung AN, Chiu PM, Leung TW, Nagley P, Wong LC, Ngan HY. High incidence of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in human ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5998–6001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Polyak K, Li Y, Zhu H, Lengauer C, Willson JK, Markowitz SD, Trush MA, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Somatic mutations of the mitochondrial genome in human colorectal tumours. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:291–293. doi: 10.1038/3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Horton TM, Petros JA, Heddi A, Shoffner J, Kaufman AE, Graham SD, Jr., Gramlich T, Wallace DC. Novel mitochondrial DNA deletion found in a renal cell carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1996;15:95–101. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199602)15:2<95::AID-GCC3>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Yeh JJ, Lunetta KL, van Orsouw NJ, Moore FD, Jr., Mutter GL, Vijg J, Dahia PL, Eng C. Somatic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations in papillary thyroid carcinomas and differential mtDNA sequence variants in cases with thyroid tumours. Oncogene. 2000;19:2060–2066. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Manion MK, Fry J, Schwartz PS, Hockenbery DM. Small-molecule inhibitors of Bcl-2. Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2006;7:1077–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, Bruncko M, Deckwerth TL, Dinges J, Hajduk PJ, Joseph MK, Kitada S, Korsmeyer SJ, Kunzer AR, Letai A, Li C, Mitten MJ, Nettesheim DG, Ng S, Nimmer PM, O'Connor JM, Oleksijew A, Petros AM, Reed JC, Shen W, Tahir SK, Thompson CB, Tomaselli KJ, Wang B, Wendt MD, Zhang H, Fesik SW, Rosenberg SH. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature. 2005;435:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nature03579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kagawa S, Gu J, Swisher SG, Ji L, Roth JA, Lai D, Stephens LC, Fang B. Antitumor effect of adenovirus-mediated Bax gene transfer on p53-sensitive and p53-resistant cancer lines. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Walensky LD, Kung AL, Escher I, Malia TJ, Barbuto S, Wright RD, Wagner G, Verdine GL, Korsmeyer SJ. Activation of apoptosis in vivo by a hydrocarbon-stapled BH3 helix. Science. 2004;305:1466–1470. doi: 10.1126/science.1099191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ravagnan L, Marzo I, Costantini P, Susin SA, Zamzami N, Petit PX, Hirsch F, Goulbern M, Poupon MF, Miccoli L, Xie Z, Reed JC, Kroemer G. Lonidamine triggers apoptosis via a direct, Bcl-2-inhibited effect on the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Oncogene. 1999;18:2537–2546. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ahn HJ, Kim YS, Kim JU, Han SM, Shin JW, Yang HO. Mechanism of taxol-induced apoptosis in human SKOV3 ovarian carcinoma cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004;91:1043–1052. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Andre N, Carre M, Brasseur G, Pourroy B, Kovacic H, Briand C, Braguer D. Paclitaxel targets mitochondria upstream of caspase activation in intact human neuroblastoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:256–260. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Cullen KJ, Yang Z, Schumaker L, Guo Z. Mitochondria as a critical target of the chemotheraputic agent cisplatin in head and neck cancer. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2007;39:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s10863-006-9059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Anderson KC, Boise LH, Louie R, Waxman S. Arsenic trioxide in multiple myeloma: rationale and future directions. Cancer J. 2002;8:12–25. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Fantin VR, Leder P. Mitochondriotoxic compounds for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2006;25:4787–4797. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Palmieri F, Bisaccia F, Capobianco L, Dolce V, Fiermonte G, Iacobazzi V, Indiveri C, Palmieri L. Mitochondrial metabolite transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1275:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Horwich AL, Kalousek F, Mellman I, Rosenberg LE. A leader peptide is sufficient to direct mitochondrial import of a chimeric protein. EMBO J. 1985;4:1129–1135. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Flierl A, Jackson C, Cottrell B, Murdock D, Seibel P, Wallace DC. Targeted delivery of DNA to the mitochondrial compartment via import sequence-conjugated peptide nucleic acid. Mol. Ther. 2003;7:550–557. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Vestweber D, Schatz G. DNA-protein conjugates can enter mitochondria via the protein import pathway. Nature. 1989;338:170–172. doi: 10.1038/338170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Chinnery PF, Taylor RW, Diekert K, Lill R, Turnbull DM, Lightowlers RN. Peptide nucleic acid delivery to human mitochondria. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1919–1928. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).D'Souza GG, Rammohan R, Cheng SM, Torchilin VP, Weissig V. DQAsome-mediated delivery of plasmid DNA toward mitochondria in living cells. J. Controlled Release. 2003;92:189–197. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Muratovska A, Lightowlers RN, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM, Smith RA, Wilce JA, Martin SW, Murphy MP. Targeting peptide nucleic acid (PNA) oligomers to mitochondria within cells by conjugation to lipophilic cations: implications for mitochondrial DNA replication, expression and disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1852–1863. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Jauslin ML, Meier T, Smith RA, Murphy MP. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants protect Friedreich Ataxia fibroblasts from endogenous oxidative stress more effectively than untargeted antioxidants. FASEB J. 2003;17:1972–1974. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0240fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Morgan J, Oseroff AR. Mitochondria-based photodynamic anti-cancer therapy. AdV. Drug DeliVery ReV. 2001;49:71–86. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Moan J, Berg K. The photodegradation of porphyrins in cells can be used to estimate the lifetime of singlet oxygen. Photochem. Photobiol. 1991;53:549–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1991.tb03669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Tijerina M, Kopečková P, Kopeček J. The effects of subcellular localization of N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymer-Mce6 conjugates in a human ovarian carcinoma. J. Controlled Release. 2001;74:269–273. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Tijerina M, Kopečková P, Kopeček J. Mechanisms of cytotoxicity in human ovarian carcinoma cells exposed to free Mce6 or HPMA copolymer-Mce6 conjugates. Photochem. Photobiol. 2003;77:645–652. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2003)077<0645:mociho>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Kessel D, Luo Y. Photodynamic therapy: a mitochondrial inducer of apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:28–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Kessel D, Castelli M. Evidence that bcl-2 is the target of three photosensitizers that induce a rapid apoptotic response. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001;74:318–322. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)074<0318:etbitt>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Gardner LC, Smith SJ, Cox TM. Biosynthesis of delta-aminolevulinic acid and the regulation of heme formation by immature erythroid cells in man. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:22010–22018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Barge J, Decreau R, Julliard M, Hubaud JC, Sabatier AS, Grob JJ, Verrando P. Killing efficacy of a new silicon phthalocyanine in human melanoma cells treated with photodynamic therapy by early activation of mitochondrion-mediated apoptosis. Exp. Dermatol. 2004;13:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2004.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Kessel D, Luguya R, Vicente MG. Localization and photodynamic efficacy of two cationic porphyrins varying in charge distributions. Photochem. Photobiol. 2003;78:431–435. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2003)078<0431:lapeot>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Lai JC, Lo PC, Ng DK, Ko WH, Leung SC, Fung KP, Fong WP. BAM-SiPc, a novel agent for photodynamic therapy, induces apoptosis in human hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cells by a direct mitochondrial action. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006;5:413–418. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.4.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Li R, Bounds DJ, Granville D, Ip SH, Jiang H, Margaron P, Hunt DW. Rapid induction of apoptosis in human keratinocytes with the photosensitizer QLT0074 via a direct mitochondrial action. Apoptosis. 2003;8:269–275. doi: 10.1023/a:1023624922787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Peng TI, Chang CJ, Guo MJ, Wang YH, Yu JS, Wu HY, Jou MJ. Mitochondrion-targeted photosensitizer enhances the photodynamic effect-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1042:419–428. doi: 10.1196/annals.1338.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Hilf R. Mitochondria are targets of photodynamic therapy. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2007;39:85–89. doi: 10.1007/s10863-006-9064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]