Abstract

Research on written language comprehension has generally assumed that the phonological properties of a word have little effect on sentence comprehension beyond the processes of word recognition. Two experiments investigated this assumption. Participants silently read relative clauses in which two pairs of words either did or did not have a high degree of phonological overlap. Participants were slower reading and less accurate comprehending the overlap sentences compared to the non-overlapping controls, even though sentences were matched for plausibility and differed by only two words across overlap conditions. A comparison across experiments showed that the overlap effects were larger in the more difficult object relative than in subject relative sentences. The reading patterns showed that phonological representations affect not only memory for recently encountered sentences but also the developing sentence interpretation during on-line processing. Implications for theories of sentence processing and memory are discussed.

Anyone who has been challenged to utter "She sells seashells by the seashore" knows that sentences with a large amount of sound repetition are hard to say. Much less appreciated, even within language research, is that this repetition also creates difficulties in comprehension, even with silent reading (Haber & Haber, 1982; Keller, Carpenter, & Just, 2003; Kennison, Sieck, & Briesch, 2003; McCutchen, Bell, France, & Perfetti, 1991; McCutchen, Dibble, & Blount, 1994; McCutchen & Perfetti, 1982; Robinson & Katayama, 1997; Zhang & Perfetti, 1993). For example, McCutchen et al. (1991) found longer sentence acceptability judgment times for visually-presented sentences with phonological overlapping words (e.g. The taxis delivered the tourists directly to the tavern) than in semantically-matched controls (The cabs hauled the visitors straight to the restaurant). Similarly, Baddeley and colleagues (Baddeley, Eldridge, & Lewis, 1981; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974) found that high amounts of phonological overlap affected the speed (but not accuracy) of detecting semantic anomalies in whole sentences.

While phonological interference effects are well known in verbal working memory research, in which phonological overlap across items in a list disrupts retention of the serial order of the list elements (Conrad & Hull, 1964; Wickelgren, 1965; Fallon, Groves, & Tehan, 1999), phonological overlap effects in reading comprehension are surprising for several reasons. First, there is not a tradition of interest in phonological information in sentence-level comprehension processes; the major foci of research are at syntactic and semantic levels. Lexical-level phonological information is generally thought to be the brief waystation on the way to semantic and grammatical information (as in models of word recognition, e.g. Seidenberg & McClelland, 1989). However, some recent work has suggested that prosodic information generated by readers influences eye fixations (Ashby & Clifton, 2005) and sentence interpretation (Fodor, 2002). Thus there may be more room for phonological-level influences in sentence comprehension than previously thought, including in silent reading. A related reason why the phonological overlap effects in reading are surprising is that there also has not been a tradition integrating phonological memory and comprehension research. Researchers studying phonological working memory have typically suggested that this memory system might be useful for word learning in children (Gathercole & Baddeley, 1989), but that it has little effect on adult comprehension processes. One source of evidence for this dissociation is that performance on simple span tasks thought to tap phonological short-term memory (e.g., word and digit span) are typically poor correlates of sentence comprehension performance (although complex span tasks, such as reading span, yield higher correlations with comprehension measures; Daneman & Carpenter, 1980). Furthermore, patients with phonological working memory impairments typically do not present with substantial deficits in sentence comprehension (Martin, 1993; Martin & Romani, 1994; Waters, Caplan, & Hildebrandt, 1987). The patient data do offer a few exceptions to this trend (Baddeley, Vallar, & Wilson, 1987; Waters, Caplan, & Hildebrandt, 1991; Papagno, Cecchetto, Reati, & Bello, 2007; Romani, 1994), and children with Specific Language Impairment may also offer evidence of correlations between phonological and grammatical performance (Bishop, 1997; Joanisse & Seidenberg, 1998; Leonard, 1997, but cf. van der Lely, 2005). Thus while there are scattered observations of phonological effects in comprehension, the dominant theoretical position has been that there is little role for phonological representations in sentence-level comprehension processes.

At the sentence level, several researchers have argued for word-based interference creating processing difficulty in certain types of relative clauses, although the interference is not described at the phonological level (Gordon, Hendrick, & Johnson, 2001; Gordon, Hendrick, Johnson, & Lee, 2006; Lewis & Vasishth, 2005; Lewis, Vasishth, & Van Dyke, 2006). These studies contrast object relative clauses, as in (1), in which the head of the relative clause (reporter) is the object of the relative clause verb (attacked) to subject relative clauses (2) in which the relative clause head is the subject of the relative clause.

Object Relative: The reporter that the senator attacked admitted the error.

Subject Relative: The reporter that attacked the senator admitted the error

Object relative sentences typically yield longer reading times than subject relatives at the main clause verb (admitted in the examples) and often at the relative clause verb (attacked) as well. Gordon et al. (2001; 2006) attributed these effects to interference between noun types, such that two common nouns such as the senator and the reporter interfere more with each other than do nouns of different types, such as one common noun and one name or pronoun. Lewis and colleagues (Lewis & Vasishth, 2005; Lewis, et al., 2006) have suggested that the interference is not over specific nouns per se but that syntactic positions interfere with one another during sentence interpretation.

Results from several other studies of relative clause comprehension have shown that these types of interference may not be the only explanation for relative clause difficulty. For example, sentences containing relative clauses are sensitive to noun animacy and sentence ambiguity effects (Gennari & MacDonald, 2008; 2009; Mak, Vonk, & Schriefers, 2008; Traxler, Morris, & Seely, 2002). These effects might be reconciled with an interference component; Gennari & MacDonald (2008; 2009), who attributed much of object relative clause processing difficulty to comprehenders’ prior experience with these and other relative clauses, noted that their experience-based account did not exclude effects of computational limitations during comprehension. Moreover, the architecture of connectionist models (such as TRACE, McClelland & Elman, 1986 also McClelland, St. John, & Taraban, 1989), in which processing is strongly affected by prior experience, clearly exhibit interference effects. Thus several theoretical positions may accommodate interference between words or other sentence elements, including ones that emphasize prior experience in accounts of comprehension difficulty.

Although these investigations of interference in relative clauses have not considered phonological effects, it is possible that phonological interference effects might be present in relative clause processing as well. In their investigation of phonological effects in sentence comprehension, Shankweiler and colleagues (Shankweiler & Crain, 1986; Shankweiler, Liberman, Mark, Fowler, & Fischer, 1979) suggested that phonological information is critical for maintaining the serial order of elements in the sentence. The unique word order of relative clauses, which interrupt the flow of words in the main clause, is thought to be a significant source of their processing difficulty, with object relatives being particularly difficult in part because the mapping between the word order and thematic relations is so different from that of other sentence types (MacDonald & Christiansen, 2002; Wells, Christiansen, Race, Acheson, & MacDonald, 2009). If retention and interpretation of word order is a challenge in processing relative clauses, then phonological information might be particularly important for their processing. If so, then relative clauses may be especially susceptible to the effects of phonological overlap.

Lewis and colleagues (Lewis & Vasishth, 2005; Lewis, et al., 2006) reject the notion that sentence processing requires any explicit representation of serial order information, but on their view too, it is plausible that phonological information could be particularly useful for relative clauses. They suggest that comprehends rely on rapid integration of previously encountered sentence constituents through cue-based retrieval processes. On this view, it might be possible to view phonological information as an additional cue (beyond semantic and syntactic ones) to distinguish different sentence constituents at the time of retrieval; phonological overlap may interfere with this process, thus leading to mis-parsing of the sentence. Under this account, if relative clause constituents are particularly difficult to retrieve, then they may be susceptible to phonological interference. Thus both this and Shankweiler and colleagues' account are consistent with the possibility that phonological representations may become important to online sentence comprehension during situations in which semantic and/or syntactic representations do not provide sufficient information to quickly encode or retrieve information about sentence constituents.

Given the importance of interference effects in accounts of processing difficulty for relative clauses, and the replicable patterns of reading times observed in these structures, relative clauses are a good candidate to examine phonological interference effects in on-line sentence processing. To date very little is known about how phonological interference plays out in on-line comprehension. Though some studies have used on-line reading measures (e.g., Kennison, 2004; Kennison, et al., 2003; Withaar & Stowe, 1998), the nature of phonological overlap effects in reading have not been particularly conducive to on-line study, in that there likely needs to be some cumulative build-up of phonologically overlapping words in order to see a contrast between overlapping and non-overlapping conditions. For this reason, as well as the sheer difficulty of manipulating phonological overlap in otherwise matched stimulus sets, researchers have not typically controlled the syntactic structure or exact location of phonological overlap within the complete stimulus set, and dependent measures have therefore often emphasized total reading times or after-sentence comprehension measures (e.g., Baddeley, et al., 1981; McCutchen, et al., 1991). In our studies, we attempted to investigate on-line processing with phonological overlap manipulations that were precisely tied to key words in particular sentence structures (object and subject relative clauses) with well-studied patterns of reading times. This method is designed to allow us to observe how phonological overlap at different locations affects on-line sentence reading patterns.

Because relative clauses seem an especially sensitive structure in which to see phonological overlap effects, our phonological manipulation was more limited than in previous studies and focused on two pairs of words. The first pair consisted of two key nouns—the head noun and embedded noun in the relative clause (e.g., reporter and senator in examples 1–2). In one condition these nouns were chosen to be phonologically overlapping (e.g. baker and banker), and in a non-overlap condition they contained little or no phonological overlap (e.g., runner and banker). The second word pair consisted of the two verbs in the sentence, one in the relative clause and the other in the main clause (e.g., attacked and admitted in 1–2). These were also phonologically similar in the overlap condition, and dissimilar in the non-overlap condition. Experiment 1 examined the effect of phonological overlap in difficult object relative sentences, as in (1) and Experiment 2 investigated the effect of overlap in moderately difficult subject relative sentences, as in (2).

Experiment 1: Phonological Overlap in Object Relative Sentences

Method

Participants

A total of 104 undergraduate students (74 female) were given course credit in introductory psychology for their participation. All were native speakers of English and ranged in age from 18–22 (M=18.9, SD=0.79).

Materials

The experimental items consisted of 24 pairs of sentences with embedded object relative clauses (see Appendix). Table 1 contains examples of the experimental sentences used in this study. One member of each pair had a high amount of phonological overlap between the head noun of the relative clause (e.g. baker) and the direct object in the relative clause (banker) and between the embedded verb of the relative clause and the main verb (sought, bought), yielding items such as The baker that the banker sought bought the house. There was not a strict criterion for the nature of the phonological overlap; many pairs rhymed, as in sought/bought, while other pairs had a large number of overlapping phonemes (and letters) but did not strictly rhyme, as in baker/banker. Overlapping words were constrained to yield a grammatical and reasonably sensible sentence.

Table 1.

Examples of experimental sentences used in Experiments 1–2 (comprehension questions and correct responses in parentheses).

| Overlap | Non-Overlap |

|---|---|

| Object Relatives, Experiment 1 | |

| The baker that the banker sought bought the house. (Did the baker seek the banker? –N) |

The runner that the banker feared bought the house. (Did the runner buy the house? – Y) |

| Subject Relatives, Experiment 2 | |

| The baker that sought the banker bought the house. (Did the baker seek the banker? –Y) |

The runner that feared the banker bought the house. (Did the banker buy the house? – N) |

The matched sentence in the non-overlap condition was similar to the phonological overlap sentence but contained little or no phonological overlap (e.g., The runner that the banker feared bought the house). The sentences with and without overlap thus differed by only two words, the first noun (baker vs. runner, Word 2 of the sentence) and the embedded verb (sought vs. feared, Word 6).

The word changes across the two overlap conditions necessarily yielded sentences with different events and participants, and it is important to exclude these meaning differences as a source of any variation in comprehension difficulty that might be observed. An independent group of participants (N=20) rated the plausibility of the experimental sentences on a scale from 1 (very implausible) to 7 (very plausible). Although whole sentence plausibility judgments are not as nuanced as having subjects make plausibility judgments or sentence completions as the sentence unfolds (e.g., Gennari & MacDonald, 2008), we used such judgments here because sentences differed by only two words, and because whole sentence judgments remain a highly useful assessment of sentence meaning. There were no plausibility difference in the overlap (M=3.78, SD=1.02) and non-overlap (M=3.89. SD=0.74) sentences (Fs < 1). Experimental sentences were also matched for overall length at nine words each, and the individual words for each overlap-non-overlap pair were matched as closely as possible for length and word frequency. Across all experimental items, there were no significant differences in overlap vs. non-overlap words in either log written frequency (Burgess & Livesay, 1998; Overlap M=5.25, SD=1.82; Non-Overlap M=5.23, SD=1.83; F(1,23) < 1, n.s.) or number of letters (Overlap M=5.60, SD = 1.6; Non-Overlap M=5.88, SD=1.5, F(1,23)=2.13, p>0.15).

Four types of sentences were developed for filler items, all of which were nine words long. Twelve items were object relative sentences, some with phonological overlap, which were included for an unrelated experiment. The remaining three filler types were passives (e.g. The scarves were worn by an old cello player); sentential complements (e.g. The pilots foresaw that the runway was too small); and sentential complements with embedded clauses (e.g. The dean begs that people who contribute be honored). A total of 24 sentences of each of these types were generated.

Two yes/no comprehension questions were generated for each sentence, one with an affirmative answer the other with a negative. Examples are contained in Table 1. Less than 10% of questions contained both members of an overlapping noun pair, and no questions contained overlapping verbs. Phonological overlap was avoided in comprehension questions to facilitate comparisons of answering time and accuracy across overlap conditions. If answers to questions for overlap sentences were longer or less accurate than answers for non-overlap sentences, these differences could be attributed to poorer comprehension of the sentence, and not to phonological overlap in the questions themselves. Similarly, having two different versions of questions for each sentence (one with a YES and one with a NO answer) increases confidence that any differences observed across overlap conditions is not due to particular questions.

Procedure

Following three practice items, each participant read 120 sentences, each with a single comprehension question. The experimental items were counterbalanced such that each participant saw 12 overlap and 12 non-overlap items, and each item was seen in only one of its two versions. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four lists that counterbalanced both overlap and yes/no questions.

Sentences and comprehension questions were presented on a computer screen, and the order of presentation was randomized for each participant. Participants read sentences using a self-paced reading paradigm (Just, Carpenter, & Wooley, 1982) in which the sentence initially appeared on screen with all nonspace characters represented by dashes. Participants pressed the space bar to view one word at a time. A comprehension question was presented on screen in its entirety immediately after the participants finished the last word of the sentence. Participants pressed keys marked YES and NO on the keyboard to answer the comprehension question and received feedback on the accuracy of their answers.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed by crossing subjects and items effects within Linear Mixed Effects Regression (LMER) analyses (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008) using the lme4 package in R. Following guidelines set out by Baayen (2008), factor labels (e.g., Word Position and Phonological Overlap) were centered prior to analysis to have a mean of 0 and a range of 1. This labeling not only minimizes collinearity between the variables, but also allows regression coefficients to be interpreted analogously to ANOVA main effects and interactions. Although this analysis outputs an estimate for each regression coefficient, along with standard errors and t-values, it is difficult to determine the number of degrees of freedom for the purposes of hypothesis testing. Hence, we adopted a standard in which a given coefficient was judged to be significant if the absolute value of t exceeded 2 (Baayen, 2008).

Each statistical model included fixed effects of our two experimental factors, Phonological Overlap and Word Position, as well as fixed effects of word length and log written frequency. Given that processing of a given word (i.e., word n) is commonly affected by processing of earlier sentence material (e.g., word n-1), analyses were performed to control for spillover from earlier sentence material. In a second round of analysis, the effects of the reading time, frequency and length of the previous word were included as fixed effects (see Vasishth & Lewis, 2006, for a similar approach and discussion of spillover effects). This latter analysis allowed us to address the extent to which reading times on a given word were affected by these properties of the previous word. Such spillover effects are a natural component of reading (Reichle & Laurent, 2006), but they have some additional importance in a study of phonological overlap, in that they may help to identify whether any overlap effects at a given word position are a result of processing at that position (including difficulty associated with retrieving earlier sentence material and integrating it with the current input), or as a result of proactive, encoding-related effects from a prior phonologically overlapping word.

In addition to each of these fixed effects, models also included a random intercept for both subjects and items. Because LMER models that do not take into account random slopes can be anti-conservative, random slopes for each of the potential parameters of interest (e.g., experimental manipulations, log frequency, length, etc.) were included in the models using forward selection (Baayen, 2008). Specifically, a series of mixed models were generated in which each of the fixed-effects variables was added as a random slope parameter first to the subjects and then two the items random effects. Parameters were included in the analysis if they improved the overall fit of the model, which was tested using log-likelihood ratio tests (Baayen, 2008). Such a procedure minimizes model complexity, and thus the possibility of a failure of convergence by virtue of including only random slopes which significantly affect the model fit. Unless otherwise indicated in the text, variables that were also included as random slopes are indicated in the tables reporting the results of each of the mixed models below.

Results

Reading times

Only trials with correct comprehension question answers were used in reading analyses. Prior to analysis, word reading times greater than 3000 ms were excluded, after which all reading times more than 3 SD from the mean at each word position and overlap condition were removed. This trimming affected 2.9% of the data.

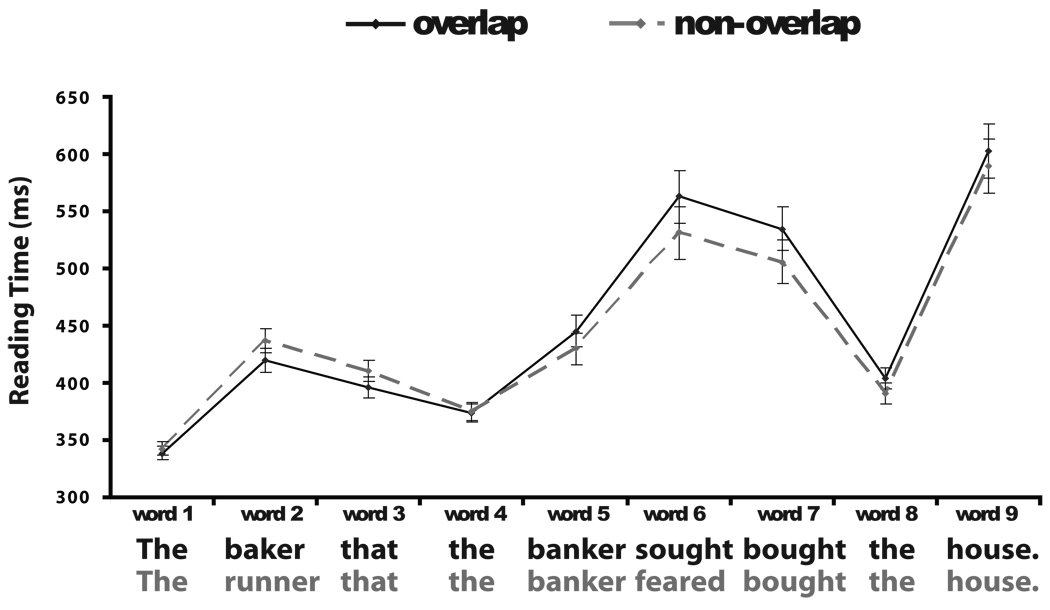

Figure 1 presents reading times for each word in the experimental sentences, and Table 2 shows the results of the two mixed-effects analyses, first factoring out the frequency and length of each word, then additionally factoring the out the reading time, frequency and length of the previous word. For this and all other analyses, sentences with phonological overlap were coded with a label of −0.5 and those without phonological overlap with a label of 0.5. Thus, regression coefficients corresponding to the factor Phonological Overlap correspond to the mean difference between the two phonological overlap conditions, with negative numbers indicating that the overlap condition was read more slowly than the non-overlap condition. Results of the first analysis revealed significant main effects of Word Position, Phonological Overlap and an interaction between the two factors. The main effect of Word Position is evident in Figure 1, as there was variability in reading speed at the different word positions, particularly at the two verbs of the sentence. Furthermore, the main effect of Phonological Overlap is explained by the fact that reading times were reliably longer for overlap than non-overlap sentences. Not surprisingly, word frequency and length were also significant predictors of reading time.

Figure 1.

Raw self-paced reading times at each word position for object relative sentence with and without phonological overlap in the nouns and verbs (experiment 1). Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval around each mean based on the estimate of the standard error for each word position from the mixed-effects analysis which incorporated fixed effects of log written frequency and word length.

Table 2.

Results of mixed effects models on raw reading times for Experiment 1 (object relative sentences). Results correspond to the model estimates of the coefficients for each fixed-effect. Random intercepts for subjects (s) and items (i) were included in all analyses, and random slopes for those variables indicated in the table.

| Model 1: Factoring Out Log Frequency and Word Length |

Model 2: Factoring Out the Effect of the Previous Word |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | T |

Random Slope |

Coefficient | SE | T |

Random Slope |

|

| Intercept | 447.04 | 34.84 | 12.83* | 479.58 | 40.27 | 11.91* | ||

| Phonological Overlap (PO) | −7.43 | 3.53 | −2.11* | s | −6.52 | 3.18 | −2.05* | s |

| Word Position (WP) | 123.2 | 11.31 | 10.89* | s,i | 112.65 | 12.56 | 8.97* | s |

| PO X WP | −34.68 | 9.68 | −3.58* | s | −27.86 | 9.41 | −2.96* | s |

| Frequency | −15.34 | 2.88 | −5.32* | i | −18.78 | 3.38 | −5.55* | i |

| Length | 17.54 | 4.12 | 4.26* | i | 15.94 | 4.51 | 3.54* | i |

| Previous Word RT | 0.16 | 0.013 | 11.69* | s | ||||

| Previous Word Frequency | −7.43 | 0.98 | −7.62* | i | ||||

| Previous Word Length | −8.43 | 0.89 | −9.47* | |||||

For this and subsequent tables, a indicates that a coefficient is a significant predictor of reading time at p < 0.05 using the criterion that | t | > 2.

Examination of Figure 1 reveals differences between the overlap and non-overlap sentences at a number of different points. In order to analyze these differences, a series of mixed-effects models were conducted which compared the effects of Phonological Overlap at each word position. Analyses included the same fixed and random effects as those presented above, but removed any fixed or random effects of word position. Results of these analyses revealed early differences at the head noun (word 2) as well as the subsequent word "that" (word 3) in which the overlapping sentences were read more quickly than the non-overlap sentences. Although these words were matched for frequency, length, and other factors, they may differ on some other dimension that affects reading times, such as the noun's plausibility as a sentence subject. Importantly, however, this effect reversed later in the sentence when readers encountered phonological overlap. Here sentences containing phonological overlap were read more slowly than those without overlap at the embedded noun (word 5), the embedded verb (word 6), the main verb (word 7) and the determiner “the” at word 8. Overlap effects at word 5 occurred before verb overlap was encountered, suggesting that noun overlap alone caused some disruption. Some of the effects at the verbs and the following determiner (word 8) may thus stem from spillover as a result of noun or verb overlap.

Results of the second set of analyses, which examined the effect of spillover from previous words on reading times, are presented in Table 2, and the follow-up tests for the effects of phonological overlap at each word position are presented in Table 3. Although the reading time, frequency and length of the previous word (i.e., word n-1) were all significant predictors of word reading time (i.e., at word n), the same main effects and interaction identified in the first analysis were again obtained. Furthermore, the analysis of phonological overlap at each word position revealed the same effects as the analysis that did not include processing on the previous word. These results suggest that phonological overlap effects are not limited to effects of spillover from encoding from one word to the next. Instead, phonological overlap also affected the ease with which earlier material was retrieved and integrated into the overall meaning of the sentence.

Table 3.

Results of mixed effects models on reading times for the effect of Phonological Overlap at each word position in Experiment 1. Results correspond to the model estimates of the coefficients for each fixed-effect. Random intercepts and slopes for Phonological Overlap were included for subjects and items.

| Model 1: Factoring Out Log Written Frequency and Word Length |

Model 2: Factoring Out the Effect of the Previous Word |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word Position | Coefficient | SE | T | Coefficient | SE | T |

| 1 | 3.63 | 3.10 | 1.17 | |||

| 2 | 16.19 | 5.41 | 2.99* | 12.33 | 5.28 | 2.34* |

| 3 | 14.03 | 4.84 | 2.90* | 15.93 | 4.94 | 3.23* |

| 4 | 1.04 | 4.09 | 0.25 | 3.98 | 3.73 | −1.07 |

| 5 | −15.11 | 7.15 | −2.11* | −16.20 | 7.02 | −2.31* |

| 6 | −1.07 | 11.78 | −2.64* | −28.89 | 11.48 | −2.51* |

| 7 | −28.35 | 9.61 | −2.95* | −25.07 | 9.88 | −2.53* |

| 8 | −13.37 | 4.71 | −2.84* | −11.63 | 4.73 | −2.46* |

| 9 | −13.14 | 11.98 | −1.10 | −7.77 | 11.82 | −0.66 |

Comprehension questions

Table 4 contains the results of two mixed effects models that examined the effects of Phonological Overlap on comprehension question accuracy and answering time. Given the coding scheme for overlap conditions noted above, positive numbers indicate that readers were more accurate for the non-overlap condition and slower for the overlap condition. This and the equivalent analysis for subject relative sentences (Experiment 2) included fixed effects of phonological overlap, and random intercepts and slopes of phonological overlap for both subjects and items. Results of this analysis revealed that subjects were less accurate and slower to answer questions about sentences containing phonological overlap (Mean Accuracy=69.0%, SD = 1.4; Mean Reaction Time = 3943 ms, SD=1549 ms) compared to those that did not contain overlap (Mean Accuracy = 75.5%, SD 1.4%; Mean Reaction Time = 3639 ms, SD = 1244 ms). Filler sentences were generally comprehended more accurately, and their mean accuracy and standard deviations are reported here: passives (M=92.1%, D=7.4%); sentential complements (M=95.7%, SD=6.3%); sentential complements with subject relatives (M=93.4%, SD=7.3%).

Table 4.

Results of mixed effects models on question accuracy and answering time for the effects of Phonological Overlap for Experiment 1 (object relatives) and Experiment 2. Results correspond to the model estimates of the coefficients for each fixed-effect. Random intercepts and slopes for Phonological Overlap were included for subjects and items.

| Experiment 1: Object Relatives | Experiment 2: Subject Relatives | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | T | Coefficient | SE | T | |||

| Accuracy | Intercept | 0.722 | 0.17 | 43.70* | Intercept | 0.84 | 0.014 | 61.91* |

| Phonological Overlap | 0.064 | 0.024 | 2.76* | Phonological Overlap | 0.090 | 0.02 | 4.50* | |

|

Answering Time |

Intercept | 3819 | 170.3 | 22.43* | Intercept | 2899 | 105 | 27.61* |

| Phonological Overlap | −281.7 | 128.6 | −2.19* | Phonological Overlap | −331.2 | 77.44 | −4.28* | |

Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 revealed reliable effects of the phonological overlap manipulation on both online (reading times) and offline (comprehension question accuracy and response time) measures of sentence comprehension. Object relative sentences containing phonological overlap in two key word pairs were more difficult to process on all of these measures compared to matched sentences without overlap. These results thus demonstrate that even this modest amount of phonological overlap can affect online sentence processing within the difficult, object relative sentence structure. Implications of these results are deferred until after presentation of Experiment 2, which examines whether phonological overlap also influences comprehension of subject relative sentences, which have a more canonical word order and which are generally found to be more easily comprehended than object relatives (Gordon, et al., 2001; Lewis, et al., 2006).

Experiment 2: Phonological Overlap in Subject Relative Sentences

Method

Participants

Undergraduate students (N=104, 75 female) were given course credit in introductory psychology for their participation. All were native speakers of English and ranged in age from 18–42 (M=19.2, SD=2.5). None had participated in the previous experiment.

Materials and procedure

The materials were the same as in Experiment 1 except that the object relatives were reworded to be subject relatives (see Appendix). Table 1 provides example subject relative sentences with and without overlap, as well as comprehension questions. As in Experiment 1, the difference between the overlapping and non-overlapping sentences in Experiment 2 occurred at only two words: the first noun (baker/runner) and the embedded verb (sought/feared). An independent group of participants (N=20) rated the experimental sentences for overall plausibility on a seven-point scale (1 = very implausible). There were no reliable differences in plausibility across the overlap (M=3.83, SD=1.28) and non-overlap (M=3.95, SD=1.33) sentences, (F’s < 1).

The procedure was the same as in Experiment 1.

Results

Reading times

Reading data were analyzed only on those trials in which a participant correctly answered the subsequent comprehension question. Prior to analysis, reading times were trimmed in the same manner as Experiment 1. In total 5.5% of the data were removed.

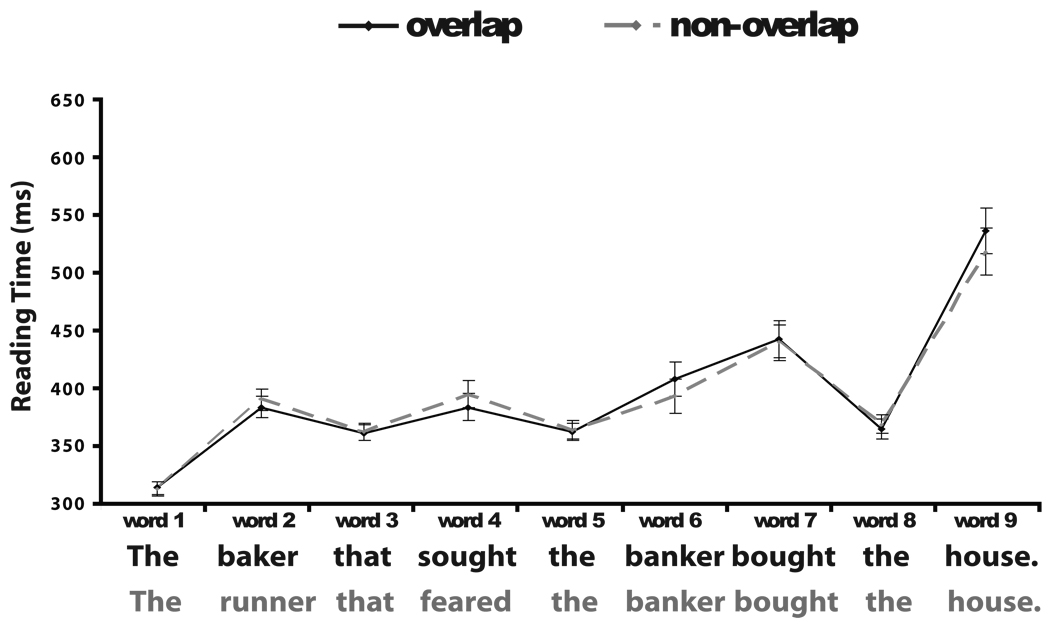

Data analyses were conducted in the same manner as in Experiment 1. Figure 2 presents raw reading times for the experimental sentences in Experiment 2, and Table 5 the results of the mixed-effects analyses. Results of this analysis revealed a main effect of Word Position and a Phonological Overlap X Word Position interaction, but no main effect of Phonological Overlap. As before, both word frequency and length were significant predictors. Table 6 contains the results of mixed-effects models of the effect of Phonological Overlap at each word position. Results of this analysis revealed an effect of Phonological Overlap at only one word position, the embedded noun (word 6).

Figure 2.

Raw self-paced reading times at each word position for subject relative sentence with and without phonological overlap in the nouns and verbs (experiment 2). Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval around each mean based on the estimate of the standard error for each word position from the mixed-effects analysis which incorporated fixed effects of log written frequency and word length.

Table 5.

Results of mixed effects models on raw reading times for Experiment 2 (subject relative sentences). Results correspond to the model estimates of the coefficients for each fixed-effect. Random intercepts for subjects (s) and items (i) were included in all analyses, and random slopes for those variables indicated in the table.

| Model 1: Factoring Out Log Frequency and Word Length |

Model 2: Factoring Out the Effect of the Previous Word |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | T | Random Slope |

Coefficient | SE | T | Random Slope |

|

| Intercept | 458.97 | 21.18 | 17.68* | 465.94 | 21.78 | 21.39* | ||

| Phonological Overlap (PO) | −0.39 | 2.45 | −0.15 | s | −1.12 | 2.53 | −0.44 | s |

| Word Position (WP) | 112.51 | 11.92 | 9.44* | s,i | 116.52 | 13.35 | 8.73* | s |

| PO X WP | −17.11 | 7.02 | −2.44* | s | −18.16 | 7.08 | −2.57* | s |

| Frequency | −14.44 | 1.7 | −8.47* | i | −14.59 | 1.8 | −8.12* | i |

| Length | 2.06 | 2.33 | 0.89 | i | 2.38 | 2.13 | 1.12 | i |

| Previous Word RT | 0.081 | 0.015 | 5.28* | s | ||||

| Previous Word Frequency | −2.65 | 0.69 | −3.82* | |||||

| Previous Word Length | −5.42 | 0.62 | −8.77* | |||||

Table 6.

Results of mixed effects models on raw reading times for the effect of Phonological Overlap at each word position in Experiment 2. Results correspond to the model estimates of the coefficients for each fixed-effect. Random intercepts and slopes for Phonological Overlap were included for subjects and items.

| Model 1: Factoring Out Log Written Frequency and Word Length |

Model 2: Factoring Out the Effect of the Previous Word |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word Position | Coefficient | SE | T | Coefficient | SE | T |

| 1 | −0.93 | 3.08 | −0.30 | −0.93 | 3.08 | −0.30 |

| 2 | 6.43 | 4.72 | 1.36 | 6.81 | 4.59 | 1.48 |

| 3 | 0.88 | 3.71 | 0.24 | −0.21 | 3.81 | −0.05 |

| 4 | 11.19 | 5.81 | 1.93 | 10.51 | 5.77 | 1.82 |

| 5 | 2.27 | 3.87 | 0.59 | −1.13 | 3.85 | −0.30 |

| 6 | −15.30 | 7.49 | −2.04* | −15.55 | 7.12 | −2.18* |

| 7 | −2.76 | 8.06 | −0.34 | −1.80 | 8.24 | −0.22 |

| 8 | 4.26 | 4.21 | 1.01 | 4.88 | 4.15 | 1.18 |

| 9 | −18.71 | 10.23 | −1.83 | −20.52 | 10.55 | −1.95 |

In order to rule out that the effects of overlap were limited to spillover from processing of a preceding word, a second set of mixed-effects analyses were performed. As in the previous experiment, the reading time, frequency and length of the previous word (i.e., word n-1) affected the reading times (of word n). Similar to Experiment 1, despite the fact that processing word n-1 significantly predicted reading times on word n, both the main effect of Word Position and the Phonological Overlap X Word Position interactions remained (see Table 5). Furthermore, follow-up analyses for the effects of Phonological Overlap at each word position revealed the same effects as the first analysis, namely, longer reading times for sentences containing phonological overlap relative to those that did not at the embedded noun (see Table 6). Thus, as with the previous experiment, the results due to phonological overlap are not simply due to spillover from reading earlier sentence material.

Similar to Experiment 1, these results thus show an effect of phonological overlap on reading times. The unexpected early advantage for the overlap noun at words 2–3 in Experiment 1 did not replicate in Experiment 2, despite the fact that these items had exactly the same words across both experiments. As can be seen in Figure 2, reading times at word 2 were numerically longer in the non-overlap condition than in the overlap condition, but this effect was not reliable. Moreover, there was no spillover effect to word 3 (that), in contrast to the Experiment 1 pattern. These results suggest that while there might have been slight differences in the difficulty of the nouns at word 2, the effect was minimal, short-lived, and in both experiments, went in the opposite direction of the phonological overlap effects.

Comprehension questions

Table 4 contains the results of mixed-effects models of the effects of Phonological Overlap for both comprehension question accuracy and answering times. The analyses were conducted in the same way as Experiment 1 and show effects of Phonological Overlap on both sentence comprehension accuracy and answering times. Similar to the previous experiment, participants were less accurate and slower to answer questions about sentences containing phonological overlap (Mean Accuracy=79.4%, SD=8.3%; Mean Reaction Time = 3060 ms, SD = 1170 ms) compared to those which did not (Mean Accuracy=89.1%, SD 6.0%; Mean Reaction Time = 2740 ms, SD = 888 ms).

Discussion

Even though subject relative clauses are generally easier than the object relatives used in Experiment 1, phonological overlap produced reliable increases in comprehension difficulty over the non-overlap condition, as measured by comprehension accuracy, comprehension latency, and reading times on a single word (the embedded object noun within the relative clause). The online measure of reading time used here, as well as the restricted locations of overlapping words, serves to pinpoint the location of overlap effects in these sentences. In this study, the overlap effect in reading times appeared to stem primarily from the pair of phonologically similar nouns, as the one reliable difference in reading times was at word 6, before the overlapping verb had been encountered. The verb overlap may also have contributed to the poorer comprehension that is observed in slower and less accurate answers to comprehension questions in overlap than non- overlap conditions.

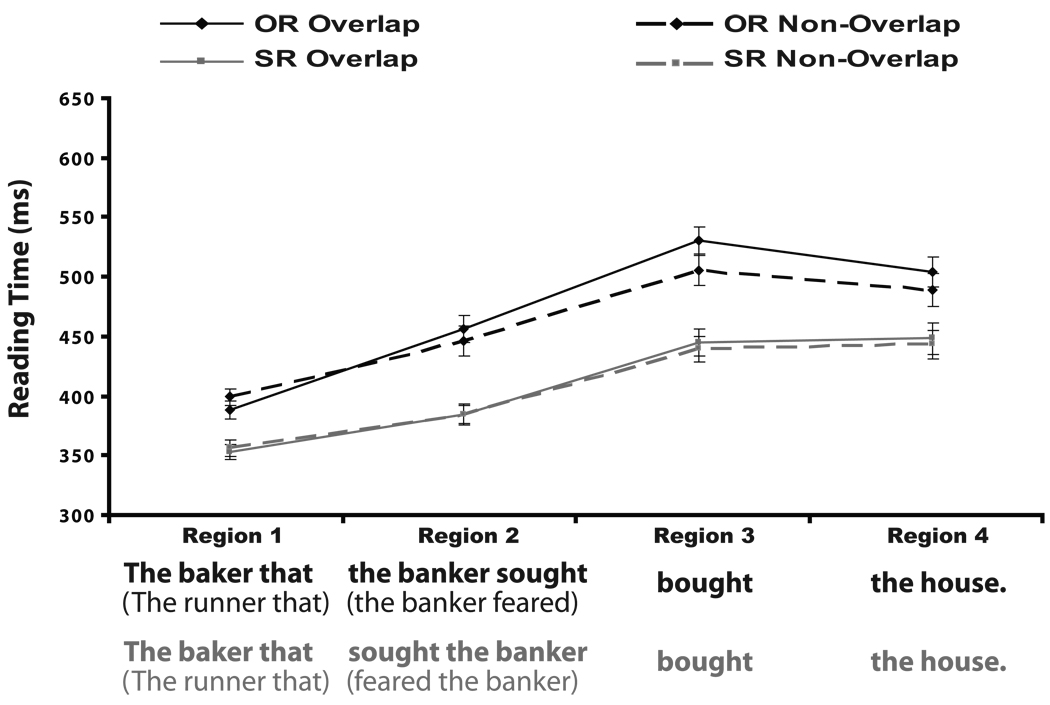

Overlap Effects in Object vs. Subject Relative Sentences

A comparison of Figure 1–Figure 2 suggests that the effects of phonological overlap may be larger for the more difficult object relative sentences in Experiment 1 than in the easier subject relatives in Experiment 2. To assess the relative size of overlap effects across experiments, analyses with Sentence Type as a factor were conducted for each dependent measure. Comparisons of subject relative (SR) and object relative (OR) sentences on a word-by-word basis can be tricky, as it is necessary to compare across different word types or sentence positions. In order to avoid this potential complication, the sentences were divided into 4 regions for the purposes of data analysis, such that each region contained words serving the same linguistic role. As shown in Figure 3, Region 1 contained the first three words of each sentence, including the head noun (e.g The baker that); region 2 contained the embedded noun phrase and verb for each sentence (e.g. sought the banker/the banker sought); region 3 contained the main verb (e.g. bought); and region 4 the direct object of the main verb (e.g. the house).

Figure 3.

Raw self-paced reading times at each region for object relative (OR) and subject relative (SR) sentences with and without phonological overlap. Subject relative sentences are denoted in italics. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval around each mean based on the estimate of the standard error for each word position from the mixed-effects analysis which incorporated fixed effects of log written frequency and word length.

Data were analyzed using a mixed-effect model which took into consideration fixed effects of Phonological Overlap, Sentence Type (object vs. subject relative) and Region. Log written frequency and word length were also entered into the analysis as fixed effects in order to control for these two variables. Random intercepts for subjects and items were included, as well as random slopes for the variables indicated in Table 7. In this instance, object relative sentences were coded with a label of −0.5 and subject relatives with +0.5, hence, negative number indicate slower reading times or better accuracy for OR compared to SR sentences. Results of this analysis showed main effects of Sentence Type and Region as well as two-way interactions between Phonological Overlap X Sentence Type and Phonological Overlap X Region. The main effect of Sentence Type is explained by the fact that subjects were significantly faster at reading SR compared to OR sentences. This effect, however, appeared in region 1, which was identical in both sentences, thus we cannot eliminate the possibility that some of the differences between SR and OR sentences came about as a result of strategic and/or individual differences across subject populations. The main effect of regions simply indicates that there were differences in reading times across regions, as subjects had a tendency to slow down more in later relative to earlier sentence regions (see Figure 3).

Table 7.

Results of mixed effects models examining whether the magnitude of the phonological overlap on reading times, question accuracy and question answering times varied across object and subject relative sentences. Fixed effects for all variables with coefficients were included in each analyses, as well as random intercepts for subjects (s) and items (i), and random slopes where indicated.

| Reading Times | Question Accuracy | Question Answering Time | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | T | Random Slope |

Coefficient | SE | T | Random Slope |

Coefficient | SE | T | Random Slope |

|

| Intercept | 475.71 | 25.56 | 18.61 | 0.78 | 0.013 | 60.34* | 3355 | 108.1 | 31.04* | |||

| Phonological Overlap (PO) | −4.35 | 3.1 | −1.40 | s,i | 0.08 | 0.016 | 4.98* | s,i | −314.9 | 74.90 | −4.20* | s,i |

| Sentence Type (ST) | −54.11 | 13.53 | −4.00* | 0.12 | 0.016 | 7.71* | −903 | 158.9 | −5.69* | |||

| Region (R) | 88.48 | 6.51 | 14.25 | s,i | ||||||||

| PO X ST | 11.68 | 4.67 | 2.50 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.45 | −40.97 | 115.4 | −0.36 | |||

| PO X R | −16.25 | 4.68 | −3.48* | s | ||||||||

| ST X R | −10.03 | 11.17 | −0.9 | |||||||||

| PO X ST X R | 16.47 | 9.34 | 1.76 | |||||||||

| Frequency | −17.27 | 2.06 | −8.40* | i | ||||||||

| Length | 9.52 | 3.17 | 3.01* | i | ||||||||

A set of mixed-effects models were run in order to determine the nature of the two way interactions above. Each analysis included the same random slopes and intercepts as the analysis in Table 7, except for the variable over which the data was collapsed (e.g., Region or Sentence Type). The Phonological Overlap X Sentype interaction is explained by the fact that while there was a main effect of Phonological Overlap for OR sentences (β = −3.42, SE = 1.70; t = −2.01) no such effect was observed for SR sentences (β = 0.28, SE = 1.31; t = 0.22). The Phonological Overlap X Region interaction is explained by the fact that signficant effects of Phonological Overlap were observed in regions one (β = 3.17, SE = 1.02; t = 3.11), three (β = −7.72, SE = 2.98; t = −2.60), and four (β = −4.57, SE = 2.25; t = −2.04) but not region two (β = −2.25, SE = 1.61; t = −1.40). Thus, across all sentence regions, the phonological overlap effect was larger for object relative sentences overall, and across both sentence types, the deleterious effects of phonological overlap were evident at the main verb and the wrap-up portion of the sentences.

The offline measures of question accuracy and answering time revealed main effects of Phonological Overlap and Sentence Type, but no interaction between these two variables. Overall, subjects were less accurate and slower to answer questions for sentences containing phonological overlap relative to those that did not. As with previous research (e.g., Gordon, et al., 2001; Lewis, et al., 2006), OR sentences were harder to comprehend than SR sentences. Subjects were significantly less accurate and slower to answer questions for OR compared to SR sentences. Thus across all measures, phonological overlap affected comprehension of both sentence types, but the only instance in which the overlap effect was larger in object relatives than subject relatives was in the on-line reading time measure.

General Discussion

Two experiments addressed the role of phonological representations during sentence comprehension through manipulating phonological overlap in sentences containing object (Experiment 1) and subject (Experiment 2) relative clauses. Results from both studies demonstrated that phonological overlap in sentences led to increases in reading times, decreases in comprehension accuracy, and increases in question answering times compared to matched, non-overlapping sentences. Thus for sentences with at least the comprehension difficulty of subject relatives, as few as two pairs of phonologically overlapping words are sufficient to disrupt comprehension processes. This is a new result, as most other studies of phonological overlap have had at least twice as many overlapping words spread broadly through the sentence.

While the study of phonological overlap in sentence processing, particularly with on-line measures and controlled structures and overlap locations is rare, the phonological similarity effect in short-term memory tasks is one of the central findings in verbal working memory research. The basic effect, that recall is poorer for lists with phonological overlap than without, has been replicated many times over (e.g. Conrad & Hull, 1964; Baddeley, 1966; Wickelgren, 1965). Interestingly, manipulations of phonological overlap affect memory for the order in which items were presented, and not memory for the items themselves (Wickelgren, 1965; Fallon, et al., 1999). This finding lends credibility to a role for phonological overlap in serial order in sentence processing, as Shankweiler et al. (1979) initially suggested. Additional research with other sentence processing measures, such as comprehension questions that directly assess serial order confusions, or sentences in which phrase order and event order do or don't conflict (e.g., Mary ate dinner after/before she went to the movie), may further illuminate the role of phonological representations in serial order processing during language comprehension.

The combination of limited overlap locations and online measures in the present study help shed light on how phonological overlap influences sentence processing. Critically, the fact that overlap effects were observed in the course of reading object and subject relative sentences suggests that phonological representations are used on-line as processing unfolds, not solely in memory for the entire sentence while answering comprehension questions or in later re-parsing if the initial sentence interpretation has gone awry (Waters, et al., 1987; Kennison, 2004). This is an important result. However, the exact source of the disruption from phonological overlap is not yet identified, and it could emerge from several different processes. First, phonological interference could be proactive (i.e., encoding-based), such that the phonological representation of prior input slows the recognition and phonological decoding of new words during reading. This is the interpretation that Haber and Haber (1982) gave to their phonological overlap effects (see also Robinson & Katayama, 1997), whereas most other researchers have assumed that the effect is retroactive, such that phonological overlap might affect the retrieval of the serial order or other representations of earlier portions of the sentence (Kennison, et al., 2003; McCutchen, et al., 1991; McCutchen & Perfetti, 1982; Shankweiler & Crain, 1986; Shankweiler, et al., 1979; Zhang & Perfetti, 1993). The present results are generally consistent with claims that phonological overlap affects both encoding and retrieval in sentence comprehension. Whereas the overlap effects observed at the nouns in object-relative sentences likely reflect encoding interference from the previously encountered overlapping noun, the effects at the verbs in object relative sentences seem to reflect retrieval-related difficulty. This latter conclusion is based on the fact that phonological overlap effects persisted at the embedded verb even after removing variance associated with the encoding of the previously encountered noun. Thus, the results at the verbs seem to reflect processing difficulties associated with integrating the phonologically overlapping nouns into the sentence. Keller et al. (2003) noted that proactive and retroactive effects are not mutually exclusive, and they found evidence for both effects in a reading and imaging study. Indeed, from the perspective of some accounts of perception and comprehension processes, such as the TRACE model (McClelland & Elman, 1986), in which the same representational units are processing new words and maintaining a representation of prior input, effects would be expected to be both proactive and retroactive.

There are actually three partially separable issues here, for which some claims exist in the literature: The first concerns the function of phonological representations during sentence comprehension—they might be maintaining serial order information and/or used in various other functions, such as cue-based retrieval, and correlations between phonological and syntactic/semantic patterns may also facilitate comprehension processes (Farmer, Christiansen & Monaghan, 2006). Second, there is the question of how phonological representations and their sentence processing functions are disrupted by phonological overlap. The overlap might disrupt memory of the serial order or other features of previously-encountered material (retroactive effects) and/or prevent complete encoding of later portions of the sentence (proactive effects), which could also have the eventual consequence of poor memory for the sentence, since some elements were not encoded properly. Third, whereas models such as TRACE predict overlap effects entirely within perceptual processes, there are other suggestions that phonological overlap effects might owe to production processes being recruited for language comprehension (e.g., Haber & Haber, 1982; Robinson & Katayama, 1997). Acheson and MacDonald (2009) argued that the effects of phonological overlap in verbal short-term memory tasks (e.g., immediate serial recall) reflect errors in speech production, rather than errors in a dedicated, phonological short-term memory system (e.g., the phonological store; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974). Similarly, MacLeod & Garrod (2003) found that hearing sentences with phonological overlap affected subsequent articulation of a target word, a result that the authors interpreted as evidence for shared production-comprehension architecture at the phonological level, consistent with Pickering and Garrod’s (2007) claims for a production role in comprehension processes. Clearly no single pattern of reading times and comprehension accuracy is going to adjudicate all of these alternatives, but it is likely that careful stimulus manipulations, in combination with other measures (e.g., fMRI; Keller, et al., 2003) will narrow the set of possibilities here.

The present patterns of data cannot uniquely identify the function(s) of phonological representations in sentence processing or the locus of interference effects. It remains plausible, for instance, that some of the overlap effects observed in the present study are a result of orthographic, in addition to phonological overlap. Furthermore, the difference in the overlap effect between OR and SR sentences may be partially driven by the fact that the overlapping items in the OR sentences are adjacent, whereas in the SR sentences they are not. Both of these possibilities could be resolved with future experimentation. Despite these potential limitations, the demonstrations of phonological overlap effects in precise locations during sentence processing nonetheless have implications for sentence processing and the role of verbal working memory in these processes, which we turn to next. Some of these observations are quite speculative, reflecting the fact that there is little current attention to phonological information in any approach to sentence comprehension.

Implications for Sentence Processing and Working Memory

Considering first methodological implications, the phonological overlap results, particularly the on-line data showing that reading time differences arise as soon as the first overlapping word has been encountered, prompt all researchers to consider the phonological makeup of alternative sentence conditions in their studies. For example, many studies of relative clause processing create condition contrasts by substituting words in otherwise matched sentences—animate vs. inanimate nouns, common noun phrases like the banker vs. names like John or pronouns like he (e.g. Gordon, et al., 2001; Warren & Gibson, 2002). These substitutions will frequently change the degree of phonological overlap across conditions, and thus phonological overlap may be modulating some of the reading time differences observed in these studies. Including degree of phonological overlap in analyses may help to ameliorate this concern.

Turning to more theoretical issues, if at least one function of phonological information is aiding in the maintenance of serial order, then the phonological overlap effects in the present study argue against a strong view of immediacy of processing, which is the idea that words are fully interpreted immediately upon being read or heard (Just & Carpenter, 1987). Logically, if words were always able to be immediately and fully interpreted into a syntactic structure (e.g., Frazier, 1987), there would never be confusion over serial order and never be room for phonological information to influence online processing, as the overlapping words would have already been given an assignment within a syntactic structure. If however, sentence interpretation is sometimes delayed because of properties of the lexical items, the sentence structure, the comprehender's attention or other factors, then the processing of given word may still be ongoing when subsequent words are encountered. An obvious example of this phenomenon is spillover effects in reading, in which the reader fixates a word in a sentence while still processing the prior word, so that properties of the prior word affect reading time on the current word. Indeed, simulations of eye movements while reading suggest that the strategy fixating the next word before information in the previous fixation has been fully processed yields more efficient word recognition than a strategy of completing all processing of one word before shifting fixation (Reichle & Laurent, 2006).

Incomplete immediacy of processing is also consistent with evidence for "post-ambiguity" constraints on processing, in which the interpretation of an ambiguous word or phrase is affected by material encountered later in the sentence—an effect that should not happen if comprehenders fully commit to a single interpretation as soon as a word is read or heard (Connine, Blasko, & Hall, 1991; MacDonald, 1994; Warren & Warren, 1970). Thus various stimulus properties such as sentence complexity or ambiguity may modulate the degree of immediacy of processing, which in turn could affect the degree to which a veridical representation of serial order must be temporarily maintained via phonological activation. On this view, the phonological interference effects that are so common in verbal working memory tasks should appear in sentence processing tasks to the extent that processing demands this temporary maintenance of phonological information. It is thus possible that phonological and other interference effects, in addition to being a cause of processing difficulty, may also be a symptom of sentence interpretation difficulty—when processing becomes difficult and slows down, then explicit maintenance of the input becomes necessary, which in turn leads to potential interference effects among incompletely-integrated words. If so, then the degree of interference from phonological overlap should vary with the difficulty or uncertainty a sentence during sentence processing, such that difficult or syntactically ambiguous sentences should be more subject to phonological overlap effects than simpler ones. The greater overall effect of overlap on reading times in the object relatives than in the subject relatives is consistent with this view, but differences among participants or strategies might have contributed to these effects. Future research might manipulate other syntactic structures to explore the relationship between difficulty and size of the overlap effect. In general, these possibilities are consistent with one realization of MacDonald & Gennari’s (2008) suggestion that the existence of interference and other memory-based effects need not be evidence against experience-based accounts of comprehension, in that the interference may emerge as a result of the experience based processing difficulty.

Although the phonological overlap manipulation in the present study may have its effects via disruption of serial order representation and maintenance, the present results are also generally consistent with a view of sentence processing in which no explicit representation of serial order is necessary (Lewis & Vasishth, 2005; Lewis, et al., 2006). In this approach, sentence processing is governed by general principles of memory such as similarity-based interference, decay and a limited capacity attention. Sentence constituents separated in time are brought together via a process of cue-based retrieval, which is subject to interference from other constituents that are maintained in memory. On this view, the effects of phonological overlap at the verbs may reflect retrieval-based (i.e., retroactive) interference of noun information during integration. This perspective raises the interesting possibility of interactions between interference at several different levels, including phonological, semantic, discourse, and noun type. Anecdotally, we have observed that sentences with both semantic and phonological overlap seem especially difficult (The plane that the train slammed rammed the crane.) A full set of these dual-overlap sentences seems impossible to construct in English, but other languages may offer more flexibility in this regard.

Finally, the current results bear an interesting resemblance to Fedorenko, Patel, Casasanto, Winawer, and Gibson’s (2009) investigation of interference between musical and linguistic processing. In their study, subject and object relative clauses were sung with a coherent melody or with an off-key element, a manipulation that is known to increase musical processing complexity. They found that the processing differences between subject and object relatives increased in the off-key condition compared to the coherent melody condition. The result is reminiscent of the current findings, in that in both cases, sound-based elements (which were generated from print during word recognition in our study) affected the difficulty of relative clause interpretation, and they had a larger effect on object than subject relatives. Previous phonological interference effects on sentence interpretation have emphasized a role for phonological information in maintaining serial order (Shankweiler & Crain, 1986; Shankweiler, et al., 1979), but the Fedorenko et al. results suggest and expanded role for sound-based information (including, to a limited degree, when generated from print). This information may be used for multiple purposes, including word recognition, serial order maintenance, speaker identification, and interpretation of linguistic and emotional prosody, many of which are known to affect sentence interpretation (Schafer, Speer, Warren, & White, 2000; Van Berkum, van den Brink, Tesink, Kos, & Hagoort, 2008). The sum of these various results suggests that sound-based information may be more important to sentence comprehension than has previously been realized, even in the case of silent reading.

| Subject Relatives with/without Phonological Overlap | Object Relatives with/without Phonological Overlap | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item # |

Sentence | Item # |

Sentence |

| 1 | The baker/runner that sought/feared the banker bought the house. | 1 | The baker/runner that the banker sought/feared bought the house. |

| 2 | The train/bus that passed/followed the crane pulled the car. | 2 | The train/bus that the crane passed/followed pulled the car. |

| 3 | The preacher/monk that fought/scared the teacher caught the athlete. | 3 | The preacher/monk that the teacher fought/scared caught the athlete. |

| 4 | The rabbi/tyrant that led/watched the rabbit fled the bear. | 4 | The rabbi/tyrant that the rabbit led/watched fled the bear. |

| 5 | The nun/friar that fights/paints the son writes the uncle. | 5 | The nun/friar that the son fights/paints writes the uncle. |

| 6 | The player/coach that met/picked the mayor bet the editor. | 6 | The player/coach that the mayor met/picked bet the editor. |

| 7 | The smoker/camper that rides/serves the joker reads the map. | 7 | The smoker/camper that the joker rides/serves reads the map. |

| 8 | The teen/chap that dates/meets the queen doubts the clerk. | 8 | The teen/chap that the queen dates/meets doubts the clerk. |

| 9 | The farmer/husband that knew/saw the charmer drew the picture. | 9 | The farmer/husband that the charmer knew/saw drew the picture. |

| 10 | The mom/dad that impresses/amazes the mime guesses the number. | 10 | The mom/dad that the mime impresses/amazes guesses the number. |

| 11 | The monster/soldier that misled/revered the mobster fed the scientist. | 11 | The monster/soldier that the mobster misled/revered fed the scientist. |

| 12 | The snail/beetle that harassed/mistreated the snake surpassed the turtle. | 12 | The snail/beetle that the snake harassed/mistreated surpassed the turtle. |

| 13 | The worker/nurse that denies/trusts the walker eyes the poet. | 13 | The worker/nurse that the walker denies/trusts eyes the poet. |

| 14 | The cook/prince that consoles/comforts the crook controls the politician. | 14 | The cook/prince that the crook consoles/comforts controls the politician. |

| 15 | The flea/moth that fooled/avoided the bee failed the ant. | 15 | The flea/moth that the bee fooled/avoided failed the ant. |

| 16 | The frog/aunt that hit/hurt the dog bit the ape. | 16 | The frog/aunt that the dog hit/bit the ape. |

| 17 | The sailor/cowboy that healed/cheated the tailor held the landlord. | 17 | The sailor/cowboy that the tailor healed/cheated held the landlord. |

| 18 | The creator/pastor that restrains/intrigues the translator entertains the author. | 18 | The creator/pastor that the translator restrains/intrigues entertains the author. |

| 19 | The driver/guide that stressed/startled the diver blessed the child. | 19 | The driver/guide that the diver stressed/startled blessed the child. |

| 20 | The punk/thug that funds/pushes the drunk finds the lawyer. | 20 | The punk/thug that the drunk funds/pushes finds the lawyer. |

| 21 | The director/employer that abuses/stalks the inspector amuses the judge. | 21 | The director/employer that the inspector abuses/stalks amuses the judge. |

| 22 | The troll/fairy that pursues/rejects the tribe subdues the demon. | 22 | The troll/fairy that the tribe pursues/rejects subdues the demon. |

| 23 | The goose/crow that chases/alarms the moose races the donkey. | 23 | The goose/crow that the moose chases/alarms races the donkey. |

| 24 | The writer/officer that hugs/favor the fighter mugs the surgeon. | 24 | The writer/officer that the fighter hugs/favors mugs the surgeon. |

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grant P50 MH644445, NICHD grant R01 HD047425, and the Wisconsin Alumni Research Fund. Portions of this work were presented at the 45th annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society, in Minneapolis, MN in 2004 and the 15th annual CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing, in Tucson Arizona in 2005. Address correspondence to Maryellen C. MacDonald, mcmacdonald@wisc.edu.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acheson DJ, MacDonald MC. Verbal working memory and language production: Common approaches to the serial ordering of verbal information. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:50–68. doi: 10.1037/a0014411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby J, Clifton C. The prosodic property of lexical stress affects eye movements during silent reading. Cognition. 2005;96:B89–B100. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baayen RH. Analyzing linguistic data: A prcatical introduction to statistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baayen RH, Davidson DJ, Bates DM. Mixed-effects modelnig with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;59:390–412. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD. Short-term memory for word sequences as a function of acoustic, semantic and formal similarity. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1966;18:362–365. doi: 10.1080/14640746608400055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Eldridge M, Lewis V. The role of subvocalisation in reading. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A: Human Experimental Psychology. 1981;33:439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Hitch G. Working Memory. In: Bower GH, editor. The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory. New York: Academic Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Vallar G, Wilson B. Sentence comprehension and phonological memory: Some neuropsychological evidence. In: Coltheart M, editor. Attention and performance XII: The psychology of reading. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, INC; 1987. pp. 509–529. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DVM. Cognitive neuropsychology and developmental disorders: Uncomfortable bedfellows. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A: Human Experimental Psychology. 1997;50A:899–923. doi: 10.1080/713755740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess C, Livesay K. The effect of corpus size in predicting reaction time in a basic word recognition task: Moving on from Kucera and Francis. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers. 1998;30:272–277. [Google Scholar]

- Connine CM, Blasko DG, Hall M. Effects of subsequent sentence context in auditory word recognition: Temporal and linguistic constraints. Journal of Memory and Language. 1991;30:234–250. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad R, Hull AJ. Information, acoustic confusion and memory span. British Journal of Psychology. 1964;55:429–432. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1964.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman M, Carpenter PA. Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior. 1980;19:450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon AB, Groves K, Tehan G. Phonological similarity and trace degradation in the serial recall task: When CAT helps RAT, but not MAN. International Journal of Psychology. 1999;34:301–307. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer TA, Christiansen MH, Monaghan P. Phonological typicality influences online sentence comprehension. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:12203–12208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602173103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorenko E, Patel A, Casasanto D, Winawer J, Gibson E. Structural intergation in language and music: Evidence for a shared system. Memory & Cognition. 2009;37:1–9. doi: 10.3758/MC.37.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodor J. Psycholinguistcs cannot escape prosody. Aix-en-Provence, France: Proceedings of the Speech Prosody 2002 Conference; Apr, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier L. Theories of sentence processing. Cambridge, MA, US: The MIT Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Baddeley AD. Evaluation of the role of phonological STM in the development of vocabulary in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Memory and Language. 1989;28:200–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gennari SP, MacDonald MC. Semantic indeterminacy in object relative clauses. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;58:161–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennari SP, MacDonald MC. Linking production and comprehension processes: The case of relative clauses. Cognition. 2009;111:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon PC, Hendrick R, Johnson M. Memory interference during language processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2001;27:1411–1423. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.27.6.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon PC, Hendrick R, Johnson M, Lee Y. Similarity-Based Interference During Language Comprehension: Evidence from Eye Tracking During Reading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2006;32:1304–1321. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.32.6.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber LR, Haber RN. Does silent reading involve articulation? Evidence from tongue twisters. American Journal of Psychology. 1982;95:409–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joanisse MF, Seidenberg MS. Specific language impairment: A deficit in grammar or processing? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1998;2:240–247. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(98)01186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA. The psychology of reading and language comprehension. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA, Wooley JD. Paradigms and processes in reading comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1982;111:228–238. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.111.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller TA, Carpenter PA, Just MA. Brain imaging of tongue-twister sentence comprehension: Twisting the tongue and the brain. Brain and Language. 2003;84:189–203. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennison SM. The effect of phonemic repetition on syntactic ambiguity resolution: implications for models of working memory. Journal of Psycholinguist Research. 2004;33:493–516. doi: 10.1007/s10936-004-2668-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennison SM, Sieck JP, Briesch KA. Evidence for a late-occurring fffect of phoneme repetition during silent reading. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2003;32:297–312. doi: 10.1023/a:1023543602202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard L. Children with Specific Language Impairment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RL, Vasishth S. An Activation-Based Model of Sentence Processing as Skilled Memory Retrieval. Cognitive Science: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2005;29:375–419. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog0000_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RL, Vasishth S, Van Dyke JA. Computational principles of working memory in sentence comprehension. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2006;10:447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald MC. Probabilistic constraints and syntactic ambiguity resolution. Language and Cognitive Processes. 1994;9:157–201. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald MC, Christiansen MH. Reassessing working memory: Comment on Just and Carpenter (1992) and Waters and Caplan (1996) Psychological Review. 2002;109:35–54. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod T, Garrod S. Where is the twist in the tongue twister? Dysfluencies following spoken and heard twister strings. Glasgow, UK: Proceedings of the AmLap; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mak WM, Vonk W, Schriefers H. Discourse structure and relative clause processing. Memory & Cognition. 2008;36:170–181. doi: 10.3758/mc.36.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RC. Short-term memory and sentence processing: Evidence from neuropsychology. Memory & Cognition. 1993;21:176–183. doi: 10.3758/bf03202730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RC, Romani C. Verbal working memory and sentence comprehension: A multiple-components view. Neuropsychology. 1994;8:506–523. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland JL, Elman JL. The TRACE model of speech perception. Cognitive Psychology. 1986;18:1–86. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(86)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland JL, St John M, Taraban R. Sentence comprehension: A parallel distributed processing approach. Language and Cognitive Processes. 1989;4:SI287–SI335. [Google Scholar]

- McCutchen D, Bell LC, France IM, Perfetti CA. Phoneme-specific interference in reading: The tongue-twister effect revisited. Reading Research Quarterly. 1991;26:87–103. [Google Scholar]

- McCutchen D, Dibble E, Blount MM. Phonemic effects in reading comprehension and text memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1994;8:597–611. [Google Scholar]

- McCutchen D, Perfetti CA. The visual tongue-twister effect: Phonological activation in silent reading. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior. 1982;21:672–687. [Google Scholar]

- Papagno C, Cecchetto C, Reati F, Bello L. Processing of syntactically complex sentences relies on verbal short-term memory: Evidence from a short-term memory patient. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2007;24:292–311. doi: 10.1080/02643290701211928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MJ, Garrod S. Do people use language production to make predictions during comprehension? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichle ED, Laurent PA. Using reinforcement learning to understand the emergence of "intelligent" eye-movement behavior during reading. Psychol Rev. 2006;113:390–408. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DH, Katayama AD. At-lexical, articulatory interference in silent reading: The 'upstream' tongue-twister effect. Memory & Cognition. 1997;25:661–665. doi: 10.3758/bf03211307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani C. The role of phonological short-term memory in syntactic parsing: A case study. Language and Cognitive Processes. 1994;9:29–67. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer AJ, Speer SR, Warren P, White SD. Intonational disambiguation in sentence production and comprehension. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2000;29:169–182. doi: 10.1023/a:1005192911512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenberg MS, McClelland JL. A distributed, developmental model of word recognition and naming. Psychological Review. 1989;96:523–568. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.96.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankweiler D, Crain S. Language mechanisms and reading disorder: A modular approach. Cognition. 1986;24:139–168. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(86)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankweiler D, Liberman IY, Mark LS, Fowler CA, Fischer FW. The speech code and learning to read. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. 1979;5:531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Traxler MJ, Morris RK, Seely RE. Processing subject and object relative clauses: Evidence from eye movements. Journal of Memory and Language. 2002;47:69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Van Berkum JJA, van den Brink D, Tesink CMJY, Kos M, Hagoort P. The neural integration of speaker and message. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20:580–591. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Lely HKJ. Domain-specific cognitive systems: Insight from Grammatical- SLI. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]