Abstract

It remains unclear whether age at onset for major psychiatric disorders is a useful marker of etiologic and genetic heterogeneity. The authors examined how heritability of schizophrenia and major affective disorders varied with age at onset. The sample was drawn from a large archival data set collected by Lionel Penrose, comprising 3,109 families with two or more members first hospitalized in Ontario between 1874 and 1944. The authors studied 1,295 sibships with schizophrenia (n = 487), major affective disorder (n = 378), both (n = 234) or neither (n = 196) of these disorders. Proportional hazards models were used to estimate how the hazard of hospitalization for each disorder (schizophrenia or major affective disorder) varied with proband age at onset, adjusted for changes in age at onset distribution between 1874 and 1944. A sibling’s risk of hospitalization for the same illness significantly increased for each 10-year decrease in age at onset of the proband both for schizophrenia (hazard ratio = 1.21, 95 % confidence interval: 1.06, 1.39), and for affective disorder (hazard ratio = 1.29, 95 % CI: 1.14,1.45). Gender of proband was unrelated to sibling risk of the same illness, and tests of interaction effects between proband age at onset and gender on sibling risk were nonsignificant.

Keywords: age of onset, cohort effect, mood disorders, schizophrenia, heredity

Introduction

The etiology of serious psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia and bipolar illness may involve susceptibility genes and subtle gene-environment interactions [3, 17]. In other multifactorial disorders with a variable age at onset (AAO), such as breast cancer and Alzheimer’s disease, earlier AAO has been a useful clinical factor to separate out more genetically homogenous entities [13, 16]. AAO in both schizophrenia and major affective disorders (e. g., bipolar disorder) varies considerably, spanning several decades. AAO has been proposed as a possible marker of etiologic and genetic heterogeneity [10, 27]. Some studies have reported an association between early onset schizophrenia and an increased risk of schizophrenia in relatives [1, 2, 20, 26, 32, 33, 35], suggesting that the early form of illness may have a higher familial liability to schizophrenia than later onset forms. However, other studies have reported either no association between early onset and familial risk in schizophrenia [19, 21], or have observed the association in males only [29, 39]. Similarly, several studies have reported an association between early onset and morbidity risk in relatives in both bipolar disorder and major depression [15, 17, 27, 31, 34, 40]. In general, the findings in major affective disorders appear more consistent than those in schizophrenia, with no suggestion that gender modifies the relationship between proband AAO and familial risk.

The main purpose of our investigation was to estimate heritability of schizophrenia and major affective disorders, and how heritability of each disorder varies with AAO. Several decades ago L. S. Penrose (reported posthumously [28]) collected a sample of 3,109 families containing two or more members first hospitalized between 1874 and 1944 with schizophrenia, major affective disorder, or another serious psychiatric disorder. Using data from this unique archival sample, we can examine whether the probability of hospitalization with the major mental illnesses in question (schizophrenia and major affective disorder) depends on the AAO of an affected sibling. In other words, is heritability stronger in younger onset cases of each of these disorders? Relative to past studies, in particular those related to schizophrenia, the Penrose sample is large and representative and, thus, has the potential to resolve the observed inconsistent findings, if indeed they result from low statistical power and selective sampling, as suggested by others [19, 21].

Since no unaffected family members were included in the Penrose sample, heritability could not be estimated using standard approaches [30]. As an alternative measure of familial risks, we, therefore, used proportional hazards survival models [7] to estimate how the hazard of hospitalization for each disorder (schizophrenia or affective disorder) varied with proband AAO (Appendix 1). We hypothesized that the hazard of hospitalization for family members would depend on proband AAO. We also examined whether gender of proband alone, or in conjunction with AAO of proband, modified our predictions.

Methods

Penrose archival data

The study sample was drawn from the archival data collected for Lionel Penrose’s study entitled “Survey of Cases of Familial Mental Illness”, published posthumously [8,28]. Penrose ascertained a large representative sample of familial mental illness by surveying all individuals who were inpatients in Ontario psychiatric hospitals between 1926 and 1944, reviewing their medical records, making personal inquiries, and identifying those with one or more family members who had ever been hospitalized with a mental illness or who had committed suicide. The total sample, comprising approximately 10 % of the total psychiatric inpatient population in Ontario, consisted of 7,339 individuals from 3,109 families. Most of these families comprised just two affected relatives, but 23.4 % had three or more affected relatives. Compared with a random sample of first admissions in Ontario psychiatric hospitals for 1943, the Penrose sample included higher percentages of individuals with schizophrenia and affective psychosis [28].

For each individual in the sample, Penrose recorded information on diagnosis, year of birth, year of first psychiatric hospitalization, gender, and how the individual was related to the relative(s) in the data set (e. g., father, sister, son, etc.). Penrose used the medical chart diagnoses to form 13 broad categories of mental illness: schizophrenia, schizoaffective, affective, arteriosclerosis, senile, paresis, Huntington disease (HD), other organic disorders, epileptic disorders, mentally defective, psychoneurotic/psychopathic conditions, undiagnosed, and suicide. The majority of individuals (60.6 %) were diagnosed with either schizophrenia or affective disorder (30.8 % and 29.8 %, respectively). In a previous study [4], we showed that the vast majority (93.7 %) of individuals in the schizophrenic category carried a diagnosis of either schizophrenia alone or schizophrenia of the catatonic, paranoid, or hebephrenic type. In the affective disorder category, 99.0 % of individuals had depressive, manic, manic-depressive, or schizoaffective diagnoses (n = 26). The proportion of subjects in the other diagnostic categories ranged from 0.97 % (for HD) to 6.5 % (for suicide). Other studies [8, 20, 38] have justified the use of similar historical clinical diagnoses for severe psychiatric illnesses, on the basis of generally conservative diagnostic practices and findings comparable to those of contemporary studies. Further, the stability of clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia and affective disorder has been shown to be adequate over illness course [11]. The institutional review board of the University of Toronto approved this study.

Study sample

To simplify analysis, sibling sets (the most common relative pair type in the data) were extracted from the data. We examined, 1,609 families containing 1,650 sibships. Our primary interest was in the diagnoses of schizophrenia and major affective disorders. The remaining diagnoses were grouped together into a category of “other psychiatric conditions”. Because an initial diagnosis of either schizophrenia or major affective disorders (e. g., bipolar illness) after age 60 years is relatively rare [5, 14, 17], we felt less confident about the validity of the diagnosis in these subjects. Therefore, families with a member who had a very late AAO, ≥ 60 years, were excluded. Our final sample consisted of 1,241 families containing 1,295 sibships and 2,868 individuals. In 27 (2.2 %) of these families, there were at least two hospitalized siblings in two different generations; these were treated as 54 independent sibships.

Measure of AAO

AAO was defined as age at first psychiatric hospitalization, previously shown to provide a reliable estimate of the AAO of major mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorders [10, 35, 37].

Statistical model

We used extensions of the Cox proportional hazards model [7, 36] to examine the distributions of age at first hospitalization (AAFH) and the effects of covariates upon these distributions (Appendix 1). In some cases, we modeled the risk of hospitalization with schizophrenia and affective disorders in the same model. In these models, each individual is at risk of hospitalization for either disorder, but the “first” diagnosis to require hospitalization is the one that will be recorded. Lunn and McNeil [25] show that by creating multiple strata, one for each diagnostic category, and by allowing all individuals to be “at risk” in each stratum until their hospitalization, estimates can be obtained that appropriately take into account the existence of the other categories. In this case, each observation was entered into the data set twice, once for each diagnosis of interest. Schizophrenic cases were considered to be censored data for the affective stratum, and vice versa.

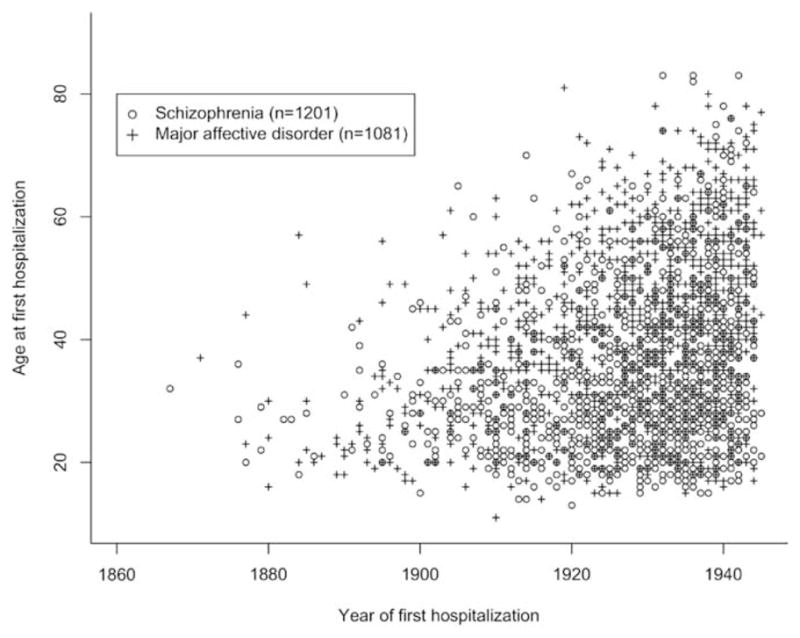

Cohort effects

Psychiatric institutions were opening across Ontario during the time period spanned by the data collection, and Penrose searched back to the earliest hospital records available. The probability of being hospitalized for a severe psychiatric disorder varied dramatically by year and region, and depended on when institutions opened. Hospitalization practices, such as which conditions warranted hospitalization or the age at which individuals were hospitalized, likely changed during this period. Furthermore, relatives of hospitalized patients might be censored from the sample if they required hospitalization before an institution or hospital bed was available, or after the collection ended in 1945. These factors resulted in cohort effects, so the age distributions for first hospitalizations changed with the calendar year; and these changes may have been diagnosis specific. Fig. 1 shows the changing distributions of AAFH for both schizophrenia and affective disorders by year of first hospitalization. Table 1 shows the number (%) of individuals in each diagnostic category by year of birth. As shown, the majority of individuals across all three diagnostic categories were born between 1875 and 1914. In terms of schizophrenia, 37.2 % of affected individuals were born between 1875 and 1894 and 49.4 % between 1895 and 1914. A reverse of this pattern was seen in individuals diagnosed with affective disorders (48.8 % and 32.0 %, respectively), suggesting that diagnostic practices as well as hospitalization practices changed over time.

Fig. 1.

Ages at first hospitalization for patients with schizophrenia and major affective disorders, by year of hospitalization. This figure includes families, subsequently excluded, where AAO was 60 or greater

Table 1.

Distribution of diagnoses in siblings (n = 2868) by year of birth

| Birth cohort | Diagnostic category

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia

|

Affective disorder

|

Other1 disorders

|

||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| < 1875 | 61 | 5.6 | 122 | 14.4 | 61 | 6.4 |

| 1875–1894 | 399 | 37.2 | 414 | 48.8 | 266 | 28.1 |

| 1895–1914 | 530 | 49.4 | 271 | 32.0 | 289 | 30.5 |

| 1915+ | 81 | 7.6 | 36 | 4.2 | 140 | 14.8 |

| Missing data | 2 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.6 | 191 | 20.2 |

| Total | 1,073 | 100.0 | 848 | 100.0 | 947 | 100.0 |

Severe psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia and affective disorder

Overall, cohort effects were considered sufficiently large, making it difficult to separate cohort effects from effects of interest, such as sibling influence. In our models (Appendix 1), we examined the impact of proband AAO on the risk among siblings. However, the difference in age between siblings was confounded with potential effects arising from the difference in the years of birth. Therefore, we non-parametrically estimated the AAO distributions by year, and then explicitly removed calendar year trends. Analysis of risks was performed on the adjusted data.

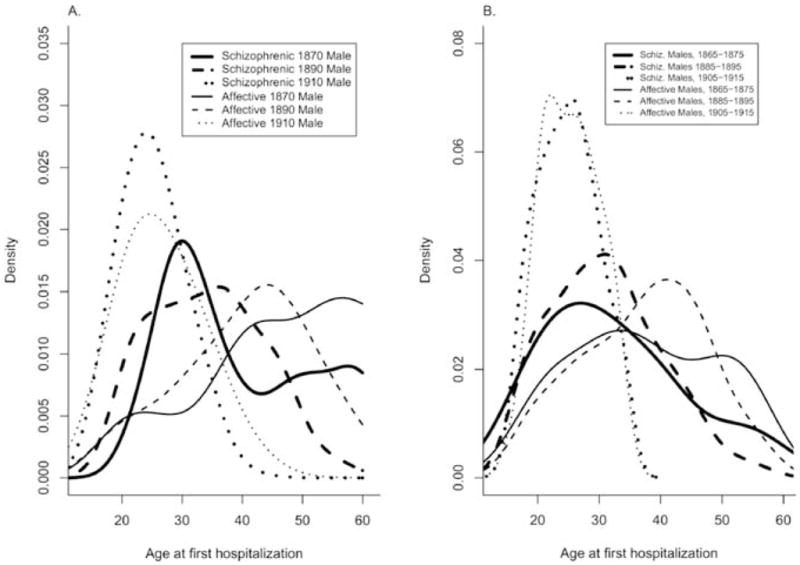

Standardization of the AAFH distributions was performed in three steps. Firstly, for each diagnosis (schizophrenia and affective disorders) and gender, we estimated a two-dimensional density for AAFH and year of birth using kde2d in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2003), using all siblings, even those with onset age ≥ 60. Then, for each individual, we used this estimated density to calculate where their AAFH fell, as a percentile, on the conditional age-distribution for their year of birth, truncated at age 60. We used the complete data set to construct the two-dimensional density distribution in order to obtain stable estimates of the density for individuals near age 60. Secondly, we constructed “reference” AAFH distributions (separately by gender and diagnosis), by using all individuals (in families with no hospitalizations over age 60) hospitalized between 1925 and 1940, inclusive. By using the latter part of the main data collection period, we hoped to obtain age distributions that were less heterogeneous due to changes in hospitalization practices, and less subject to censoring. These distributions formed the reference distributions to which we standardized. Thirdly, we mapped the individual’s percentile obtained in the first step onto the appropriate reference distribution from the second step, adjusting for censoring at the end of the data collection in 1945. Fig. 2 shows AAFH distributions before and after adjustment for cohort effects.

Fig. 2.

Estimated distributions of age at first hospitalization by diagnosis and year of birth. Families containing an individual hospitalized at age 60 or greater were excluded. A. Unadjusted: Bivariate density distributions for year of birth and AAO were estimated by a two-dimensional kernel smoother. Conditional density estimates for AAO are shown for three different years. B. Adjusted: Conditional density distributions (shown in A) for all years of birth were adjusted to the observed distribution of AAO for those hospitalized between 1925 and 1940, inclusively. Each individual was then assigned an adjusted AAO, corrected for censoring of the study sample in 1945. Smoothed (univariate) densities are shown for the adjusted AAOs of patients born in three different decades

Random proband model

A schizophrenic proband was randomly sampled from each family containing at least one schizophrenic sibling. The hazard of hospitalization with schizophrenia or affective disorder was then estimated for the remaining siblings using the stratified proportional hazards model. A similar strategy was used to sample an affective proband and examine hazards of hospitalization among siblings. Parameters from this model were interpreted across families. We then estimated how the hazard of hospitalization depended on the AAO of the proband, adjusting for other covariates such as gender. Ten data sets were created by randomly selecting probands ten times, and the results show the average estimates across the ten data sets [24].

Familial correlation

Family members may resemble each other more than unrelated individuals. They are more likely to be diagnosed with the same disorder, especially if there is a genetic component to the disorder. Furthermore, for the same diagnosis, two related individuals may have more similar ages of first hospitalization than unrelated people with the same diagnosis. Correlation between remaining siblings was taken care of through a robust jackknife correction to the variances that allowed for clustering. It was interesting to note that, in fact, the corrections to the variances were in general very small.

For the descriptive analysis, family-specific average ages at onset were summarized (means and standard deviations). Testing for significant differences in AAO was performed using analysis of variance including family as a factor, hence familial clustering in AAO should not bias significance levels. The median AAO for schizophrenia and for affective disorder was 31.0 and 39.0 years, respectively. This was similar to the mean AAO for both disorders (32.3 and 38.6 years).

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the 1,295 sibships included in the study sample, 1,099 contained at least one member diagnosed with schizophrenia or major affective disorder, and 196 contained only members with a severe psychiatric condition other than schizophrenia or affective disorder. In the 487 sibships with at least one member diagnosed with schizophrenia but no member with major affective disorder, the mean AAO of the 806 schizophrenic siblings (420 females and 386 males) was 32.7 years (SD = 9.7). Males had an earlier AAO than females (31.4 years vs. 34.8 years; F = 9.22, p = 0.0026; ANOVA adjusting for gender and family, nested within gender group). The mean AAO was slightly earlier in sibs from sibships with two or more schizophrenic members (n = 279) relative to all schizophrenic sibs (31.7 years vs. 32.7 years, p = 0.021). In the 378 sibships with affective disorder but no schizophrenic siblings, the mean AAO of affective disorder among the 576 sibs (335 females and 241 males) was 39.8 years (SD = 10.6), significantly later than that for schizophrenia (F = 59.3, df = 1, p ≤ 0.0001). There was no significant difference in AAO between males and females (p = 0.77). Again the mean AAO was slightly earlier in sibs from sibships with two or more affective members (n = 182) relative to all affective sibs (38.9 years vs. 39.8 years, p = 0.016). In the 234 sibships with at least one schizophrenic and at least one affective sibling, the mean AAO for the 539 sibs (308 females and 231 males) with either schizophrenia (n = 267) or with major affective disorder (n = 272) was 34.0 (SD = 8.9). This was later than that for individuals from sibships with schizophrenic siblings but no affective siblings, but earlier than that for individuals from sibships with affective siblings but no schizophrenic siblings (F = 28.6, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Males with either schizophrenia or affective disorder from these mixed sibships demonstrated a nonsignificantly lower AAO than females with schizophrenia or affective disorder (30.8 years vs. 35.7 years; F = 2.39, df = 1, p = 0.12). The mean AAO of schizophrenia and of affective disorder in these mixed sibships did not differ significantly from that in schizophrenia-only or affective disorder-only sibships.

AAO of proband and morbidity risk in sibling(s)

Table 2 presents the hazard of hospitalization for schizophrenia in siblings of a schizophrenic proband and for affective disorder in siblings of an affective proband. A sibling’s hazard of schizophrenia significantly increased for each 10-year decrease in AAO of schizophrenic proband (HR = 1.21, 95% confidence interval: 1.06, 1.39). A similar, but slightly stronger, association was seen for affective disorders, with sibling risk of affective disorder increasing for each 10-year decrease in AAO of the proband (HR = 1.29, 95% confidence interval: 1.14, 1.45). The magnitude of this increased risk in siblings was relatively small, however, for both disorders, averaging about 20–30 %.

Table 2.

Increased hazard of diagnosis in siblings as a function of proband’s age at first hospitalization, where proband and sibling have the same diagnosis (schizophrenia or affective disorder)

| Disease under consideration in sibling of proband | Gender

|

All families

|

Subset with exactly two siblings1

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proband | Sibling | Hazard ratio2 | 95% CI | p | Hazard ratio2 | 95% CI | p | |

| Schizophrenia | Either | Either | 1.21 | 1.06–1.39 | 0.010 | 1.22 | 1.05–1.42 | 0.010 |

| Male | Male | 1.40 | 1.06–1.85 | 0.039 | ||||

| Male | Female | 1.37 | 1.06–1.78 | 0.052 | ||||

| Female | Male | 1.17 | 0.92–1.48 | 0.27 | ||||

| Female | Female | 1.15 | 0.88–1.50 | 0.31 | ||||

| Affective disorder | Either | Either | 1.29 | 1.14–1.45 | <0.0001 | 1.34 | 1.16–1.54 | <0.0001 |

| Male | Male | 1.28 | 0.98–1.68 | 0.12 | ||||

| Male | Female | 1.28 | 0.98–1.66 | 0.12 | ||||

| Female | Male | 1.28 | 0.96–1.72 | 0.16 | ||||

| Female | Female | 1.38 | 1.17–1.63 | 0.0002 | ||||

This subset contained 87% of the 487 sibships with at least one member diagnosed with schizophrenia but no member with major affective disorder, 86% of the 378 sibships with at least one member diagnosed with major affective disorder but no member with schizophrenia, and 71% of the 234 sibships with at least one schizophrenic sibling and at least one affective disorder sibling

Note: Mean relative increase in hazard for proband 10 years younger at first hospitalization. Estimates, 95% confidence intervals CI, and p-values were estimated for ten random proband selections, and the averages reported

In families with many hospitalized members, it is more likely that at least one of the family members is hospitalized at a young AAO. To remove this potential bias due to family size, we restricted the analysis to only families with exactly two hospitalized siblings (Table 2). In these sibships, we still see an increased hazard of hospitalization for schizophrenia associated with younger onset proband (schizophrenic or affective).

As also shown in Table 2, when gender of the proband and gender of the sibling were considered, with few exceptions hazard ratios were quite similar in magnitude. Power to detect significant AAO effects was, however, lower due to the reduced sample sizes in subgroups. There was a suggestion of a larger effect of the male proband AAO on hazard of schizophrenia in both male and female siblings. In contrast, for affective disorders, the hazard ratio was largest when examining the effect of female proband AAO on the hazard among female siblings. However, tests of interaction were nonsignificant.

Specificity of effect between AAO of proband and morbidity risk in sibling(s)

Since the vast majority of individuals in the sample suffered from a psychotic illness, it is possible that the observed similarity of effect of proband AAO between schizophrenia and affective disorder may reflect shared risk factors for psychosis in general. We found that siblings of randomly selected schizophrenic probands had a significantly increased risk of affective disorders for each 10-year decrease in proband AAO (HR = 1.50, 95% confidence interval: 1.28, 1.75), but the risk of other psychiatric conditions was not increased (HR = 1.15, 95% confidence interval: 0.96, 1.37). A parallel analysis showed that, for siblings of affective disorder probands, risk of schizophrenia was significantly increased with each 10-year decrease in proband AAO (HR = 1.32, 95% confidence interval: 1.17, 1.49), and, to a lesser extent, risk of other psychiatric conditions (HR = 1.20, 95% confidence interval: 1.04, 1.38).

Gender of proband and morbidity risk in sibling(s)

In male siblings, we found an increased risk of schizophrenia (HR = 1.25, 95% confidence interval: 0.96, 1.65), but a decreased risk of affective disorder (HR = 0.83, 95% confidence interval: 0.58, 1.18), although these trends were nonsignificant. However, neither gender of schizophrenic proband nor gender of affective disorder proband was related to sibling risk of schizophrenia or affective disorder. As expected, it was the diagnosis of proband that significantly predicted schizophrenia or affective disorder in siblings. A sibling of a male schizophrenic proband had a greater increased risk of a schizophrenia diagnosis than that of a sibling of a male affective disorder proband (HR = 1.84, 95% confidence intervals: 1.08, 3.14), while the risk of affective disorder was significantly reduced (HR = 0.43, 95% confidence intervals: 0.25, 0.75). Similarly, a sibling of a female schizophrenic proband had a significantly greater risk of schizophrenia than a sibling of a female affective disorder proband (HR = 2.30, 95% confidence intervals: 1.57, 3.38), whereas the risk of affective disorder was significantly reduced (HR = 0.58, 95% confidence intervals: 0.37, 0.93). Of further note, AAO of proband with schizophrenia or affective disorder remained predictive of morbidity risk in siblings in the context of proband gender and diagnosis (HR = 1.26, 95% confidence interval: 1.12, 1.40, p = 0.001). Gender of the sibling did not modify this relationship.

Discussion

As in other multifactorial diseases, AAO may be a useful clinical characteristic to separate out more homogenous and etiologically distinct forms of both schizophrenia and major affective disorders. We found evidence for increased heritability associated with a younger AAO of proband. This relationship was independent of gender of proband, gender of sibling, and family size. However, as shown in Table 2, the magnitude of the observed association between early onset of proband and morbidity risk in siblings was modest. This may explain why some past studies with relatively small samples may have either failed to detect an association [19], or observed the association in males only [29,39]. Interestingly, the magnitude of the association was quite similar for both schizophrenia and affective disorder and when probands had schizophrenia and their siblings had affective disorder, and vice versa. This similarity between the two disorders in AAO effects on heritability might suggest shared genetic or environmental risk factors. Although controversy remains about the genetic relationship between schizophrenia and affective illness, there is increasing evidence for overlap. For instance, Berrettini [6] reviewed epidemiological, family, and molecular linkage studies in schizophrenia and bipolar disorders and concluded that the two disorders may share some genetic risk factors.

Our results also suggest an increased heritability of schizophrenia and affective disorders in younger onset probands relative to other psychotic conditions. This may reflect the cross-heritability of these two disorders [6], or alternatively diagnostic misclassification. Although judged to be adequately stable, the stability of an initial clinical diagnosis of affective psychoses has been shown to be lower than that of an initial clinical diagnosis of schizophrenic psychoses, with considerable movement from affective disorders towards schizophrenia [11]. It is also possible that the increased heritability of schizophrenia and affective disorders in younger onset probands relative to other psychotic conditions may reflect the considerable diagnostic heterogeneity within the group of other psychiatric conditions, including both functional and organic psychoses. On the other hand, the slightly increased risk of other conditions in siblings of probands with younger onset schizophrenia or affective disorder may indicate the magnitude of residual bias associated with the strong cohort effects in the data. If this was the case, it is worthwhile to note that this bias would not fully account for the overall findings (Table 2).

We observed that the magnitude of association between younger onset schizophrenic probands and risk of affective disorders in siblings was somewhat greater than that of schizophrenia in siblings, and vice-versa. This was likely due to the selection of the random proband. When one selects a schizophrenic proband, the risk of hospitalization with schizophrenia among siblings is somewhat reduced relative to the risk of hospitalization with another psychiatric condition, just due to the ascertainment and the fact that all siblings were hospitalized with some disorder.

The results of our study also provided data on proband gender and familial risk. The schizophrenia literature has suggested that gender may be another useful clinical characteristic to separate out more homogenous and etiologically distinct forms of illness. AAO of schizophrenia was on average 3 years younger in males than females, while AAO of affective disorder was similar in both males and females. Some have speculated this gender difference in AAO of schizophrenia could occur if one or more of the genes for schizophrenia is sex-linked [9, 10, 28], although there is no evidence for this. Alternatively, the actions of autosomal genes may be modulated differently in the two sexes. Our results, however, showed that gender of proband, with schizophrenia or affective disorder was not significantly associated with morbidity risk in siblings. Further, there was no evidence of a significant interaction effect between proband gender and AAO on familial risk, previously suggested by others [29, 39]. However, different results might be seen if the sample were not constrained to only hospitalized individuals.

Some methodological limitations of our study should be acknowledged. If the affective disorders in this archival sample include less serious forms of psychopathology than schizophrenia, hospitalization rates in siblings with affective disorders may be lower than that observed for the schizophrenic siblings (which appear to be close to 100 %), and this could have biased our results. There is no compelling reason to believe that the hospitalization rates for siblings with schizophrenia and those with affective disorders would differ dramatically. The vast majority of individuals included in Penrose’s sample suffered from a severe psychotic disorder. Over the years, it has been consistently reported in the literature that most individuals with serious psychotic disorders are hospitalized [22]. Another potential limitation relates to the use of historical clinical diagnoses. We justified their use on the basis of generally conservative diagnostic practices and findings comparable to those of contemporary studies in terms of the proportions of relevant diagnoses (e. g., approximately equal percentage of individuals in schizophrenia and affective disorder categories) and demographic characteristics (e. g., later AAO for affective psychotic disorders than schizophrenia). Nevertheless, the mean AAO for schizophrenia is older than that typically reported in contemporary samples. It is possible that some of the siblings with a later onset, in particular those first hospitalized after age 45 years, would not receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia, using current narrow diagnostic criteria. This raises the question as to whether the observed effect of proband younger AAO on siblings’ risk of schizophrenia is simply due to a portion of later onset probands in the Penrose data set being incorrectly diagnosed with schizophrenia. This explanation, however, is inconsistent with the results of the analysis, showing an increase in sibling risk for each 10-year decrease in proband AAO. Plots of this effect showed that it was quite linear across age (results not shown). Thus, the effect of AAO on sibling risk is seen even among young AAO probands where diagnostic inaccuracies may be less prevalent. Finally, this study focused predominantly on psychotic disorders that may be related to familial liability to schizophrenia and to affective disorders. It is, therefore, unclear whether our findings are generalizable to all possible schizophrenia-related disorders, including schizotypal and paranoid personality disorders [18] and the full spectrum of affective disorders. The utility of early AAO in contemporary genetic studies of schizophrenia and affective disorders may, therefore, vary depending on the definition of the phenotype used. Moreover, the diagnostic heterogeneity of the other psychiatric condition group makes it difficult to rule out the possibility that the observed increased heritability of schizophrenia and affective disorder in siblings of younger onset probands reflects an underlying vulnerability to psychosis in general, rather than to schizophrenia or affective disorder.

In conclusion, the results are consistent with previous studies that suggest early AAO reflects enhanced familial liability to schizophrenia and to affective disorder and that gender of proband appears to be less important to familial risk. The extent to which early AAO indicates a genetic liability to either schizophrenia or affective disorder, and the relative influence of other environmental or biological factors on AAO, however, remain unknown. Although early AAO may not reflect increased genetic susceptibility for all forms of schizophrenia and affective disorder, these results suggest that early AAO may be a useful strategy in genetic studies of both disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Cyril Greenland, PhD, for contributions and longstanding interest in the work of Lionel Penrose. The authors would like to thank Sarah Alley for help in the preparation of the manuscript. This study was supported in part by funding Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute, the Mathematics of Information Technology and Complex Systems (Networks of Centres of Excellence Program) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Appendix 1

In these survival models, we are modeling the hazard of first hospitalization as a function of the proband AAO. The age-specific hazard of first hospitalization is the probability of hospitalization at age A given that the individual has not been hospitalized immediately prior to age A. For first hospitalization with schizophrenia, we write the hazard as h(ASZ). The proportional hazards model separates a baseline hazard from covariate effects x, so that h(ASZ | x) = h0(ASZ) exp(bSZ xSZ). The baseline hazard h0(ASZ) will be a function of incidence rates of other disorders, conditional on sampling a proband with schizophrenia. It cannot be used to estimate population prevalence of schizophrenia among siblings of a proband, since only hospitalized siblings are in the data set. The covariate of interest is the schizophrenic proband age at first hospitalization, AAOSZ.

Hazard are functions of the probability of being hospitalized before age A, P(a ≤ A). Let H denote the fact that a sibling has been hospitalized; let I(SZ) denote that the proband is schizophrenic.

| (1) |

If unaffected siblings were also sampled, we would be able to estimate

| (2) |

This equality holds since P(a ≤ A | not(H), I(SZ), AAOI(SZ)) = 0.

Note that P(H | I(SZ), AAOI(SZ)), the probability of a sibling being hospitalized, may depend on the AAO of the proband. So the covariate effect being measured in (1) and in (2) may be different. Nevertheless, we assume that the effect of the proband AAO in P(H | I, AAO) is similar for schizophrenics and affective disorders. With this assumption, we can compare the estimates bSZ and bAF from (1).

Contributor Information

Dr. Janice A. Husted, Department of Health Studies and Gerontology, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1, Canada, Tel.: +1-519/888-4567 Ext. 5129, Fax: +1-519/746-2510.

Celia M. T. Greenwood, Program in Genetics and Genomic Biology, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Anne S. Bassett, Clinical Genetics Research Program, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

References

- 1.Albus M, Scherer J, Hueber S, Lechleuthner T, Kraus G, Zausinger S, Burkes S. The impact of familial loading on gender differences in age at onset of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89:132–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alda M, Ahrens B, Lit W, Dvorakova M, Labelle A, Zvolsky P, Jones B. Age of onset in familial and sporadic schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:447–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassett AS, Chow EWC, O’Neill S, Brzustowicz LM. Genetic insights into the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:417–430. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassett AS, Husted J. Anticipation or ascertainment bias in schizophrenia? Penrose’s familial mental illness sample. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:630–637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellivier F, Golmard J-L, Rietschel M, Schulze T, Malafosse A, Preisig M, McKeon P, Mynett-Johnson L, Henry C, Leboyer M. Age at onset in Bipolar I affective disorder: Further evidence for three subgroups. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:999–1001. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berrettini WH. Are schizophrenic and bipolar disorders related? A review of family and molecular studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:531–538. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00883-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) J Royal Stat Soci Brit. 1972:34. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crow TJ. A note on “Survey of cases of familial mental illness” by LS Penrose. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;240:314–315. doi: 10.1007/BF02279760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crow TJ. Sex chromosomes and psychosis: The case for a pseudoautosomal locus. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:675–683. doi: 10.1192/bjp.153.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLisi LE. The significance of age of onset for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:209–215. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrester A, Owens DGC, Johnstone EC. Diagnostic stability in subjects with multiple admissions for psychotic illness. Psychol Med. 2001;31:151–158. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799003116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gentleman R, Ihaka R. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.George-Hyslop PH, Haines JL, Farrer LA, Polinsky R, Van Broeckhoven C, Goate A, MacLachlan DRC. Genetic linkage studies suggest that Alzheimer’s disease is not a single homogeneous disorder. Nature. 1990;347:194–197. doi: 10.1038/347194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorwood P, Leboyer M, Jay M, Payan C, Feingold J. Gender impact and age at onset in schizophrenia: Impact of family history. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:208–212. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grigoroiu-Serbanescu M, Martinez M, Nöthen M, Grinberg M, Sima D, Propping P, Marinescu E, Hrestic M. Differential transmission patterns in Bipolar I disorder with onset before and after age 25. Am J Med Genet (Neuropsychiatric Genetics) 2001;105:765–773. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall JM, Lee MK, Newman B, Morrow JE, Anderson LA, Huey B, King M-C. Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science. 1990;250:1684–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.2270482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson L, Andersson-Lundman G, Åberg-Wistedt A, Mathé A. Age of onset in affective disorder: its correlation with hereditary and psychosocial factors. J Affect Disord. 2000;59:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendler KS, Diehl SR. The genetics of schizophrenia: A current, genetic-epidemiologic perspective. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19:261–285. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendler KS, Karkowski-Shuman L, Walsh D. Age at onset in schizophrenia and risk of illness in relatives. Results from the Roscommon Family Study. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:213–218. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendler KS, MacLean CJ. Estimating familial effects on age at onset and liability to schizophrenia: I. Results of a large sample family study. Genet Epidemiol. 1990;7:409–417. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370070603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kendler KS, Tsuang MT, Hays P. Age at onset in schizophrenia: A familial perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:881–890. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800220047008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Link B, Dohrenwend B. Formulation of hypothesis about the ratio of untreated to treated cases in the true prevalence studies of functional psychiatric disorders in adults in the United States. In: Dohrenwend BP, Dohrenwend BS, Schwartz Gould M, Link B, Neugebauer R, Wunsch-Hitzig R, editors. Mental Illness in the United States: Epidemiologic Estimates. Praeger; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipsitz SR, Dear KB, Zhao L. Jackknife estimators of variance for parameter estimates from estimating equations with applications to clustered survival data. Biometrics. 1994;50:842–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical analysis with missing data. J. Wiley and Sons; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lunn M, McNeil D. Applying Cox regression to competing risks. Biometrics. 1995;51:524–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maier W, Lichtermann D, Minges J, Heun R, Hallmayer J. The impact of gender and age at onset on the familial aggregation of schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;242:279–285. doi: 10.1007/BF02190387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.OMahoney E, Corvin A, O’Connell R, Comerford C, Larsen B, Jones R, McCandless F, Kirove G, Cardno AG, Craddock N, Gill M. Sibling pairs with affective disorders: Resemblance of demographic and clinical features. Psychol Med. 2002;32:55–61. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penrose LS. Survey of cases of familial mental illness. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;240:315–324. doi: 10.1007/BF02279760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pulver AE, Liang KY. Estimating effects of proband characteristics on familial risk: II. The association between age at onset and familial risk in the Maryland schizophrenia sample. Genet Epidemiol. 1991;8:339–350. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370080506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Risch N. Linkage strategies for genetically complex traits. I. Multilocus models. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46:222–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schurhoff F, Bellivier F, Jouvent R, Mouren-Simeoni MC, Bouvard M, Allilaire JF, Leboyer M. Early and late onset bipolar disorders: two different forms of manic-depressive illness? J Affect Disord. 2000;58:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sham PC, Jones P, Russell A, Gilvarry K, Bebbington P, Lewis S, Toone B, Murray R. Age at onset, sex, and familial psychiatric morbidity in schizophrenia: Camberwell Collaborative Psychosis Study. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:466–473. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sham PC, MacLean CJ, Kendler KS. A typological model of schizophrenia based on age at onset, sex and familial morbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89:135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Somanath CP, Jain S, Reddy YC. A family study of early-onset bipolar I disorder. J Affect Disord. 2002;70:91–94. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suvisaari JM, Taukka J, Tanskanen A, Lonnqvist JK. Age at onset and outcome in schizophrenia are related to the degree of familial loading. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:494–500. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Therneau TM. Extending the Cox model. Mayo Clinic; Rochester, Minnesota: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuang MT. A study of pairs of sibs both hospitalized for mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1967;113:283–300. doi: 10.1192/bjp.113.496.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogler GP, Gottesman II, McGue MK, Rao DC. Mixed-model segregation analysis of schizophrenia in the lindelius Swedish pedigrees. Behav Genet. 1990;20:461–472. doi: 10.1007/BF01067712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waddington J, Youssef H. Familial-genetic and reproductive epidemiology of schizophrenia in rural Ireland: age at onset, familial morbidity risk and parental fertility. Acta Psychiatr. 1996;93:62–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weissman MM, Gershon ES, Kidd KK, Prusoff BA, Leckman JF, Dibble E, Hamovit J, Thompson WD, Pauls DL, Guroff JJ. Psychiatric disorders in the relatives of probands with affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:13–21. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790120015003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]