Abstract

The variations in the three regions of the Helicobacter pylori vacA gene, the signal (s1 and s2), intermediate (i1 and i2) and middle regions (m1 and m2), are known to cause the differences in vacuolating activities. However, it was unclear whether these vacA genotypes are associated with the development of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer in the Middle East. The aim was to identify the prevalence of vacA genotypes in the Middle East and the association with gastroduodenal diseases. We investigated the relationship of vacA genotypes to H. pylori-related disease development by meta-analysis using previous reports of 1,646 patients from the Middle East. The frequency of the vacA s1, m1 and i1 genotypes in the Middle Eastern strains was 71.5% (1,007/ 1,409), 32.8% (427/1,300) and 40.7% (59/145), respectively. Importantly, the frequency of vacA s- and m-region genotypes significantly differed between the north and south parts of the Middle East countries (P<0.001). The vacA genotypes significantly increased the risk of gastric cancer (odds ratio [OR]: 4.02, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.98–8.14 for the s1 genotype; 2.50, 1.62–3.85 for m1; 5.27, 1.97–14.1 for s1m1; 15.03, 4.69–48.17 for i1) and peptic ulcers (OR: 3.07, 95% CI: 2.08–4.52 for s1; 1.81, 1.36–2.42 for m1). The cagA-positive genotype frequently coincided with the s1, m1 and i1 genotypes. The vacA s- and m-region genotypes may be useful risk factors for gastrointestinal diseases in the Middle East, similar to European and American countries. Further studies will be required to evaluate the effects of the i-region genotype.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infect in the gastric mucosa of 50% of the world’s population and infection levels exceed 70% of the population in developing areas, such as Latin America and Africa [1–3]. The Middle Eastern countries were also reported to have a high prevalence of H. pylori infection, such as 86% in Turkey [4] and more than 90% in the Iranian population [5]. H. pylori infection is closely associated with the occurrence of peptic ulcers, gastric hyperplastic polyps, gastric cancer and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [6–9]. Therefore, it is considered to have a higher incidence of H. pylori-related diseases in developing countries with higher infection rate. However, the incidence of gastric cancer in the Middle East (e.g. 8.28/100,000 in Turkey, 4.58/100,000 in Kuwait and 6.64/100,000 in Jordan) are relatively lower than that in East Asia (e.g. 124.63/ 100,000 in Japan and 48.25/100,000 in Korea) and South America (e.g. 33.22/100,000 in Colombia and 38.73/100,000 in Chile) (http://www-dep.iarc.fr/). The detailed reasons for this phenomenon are unknown, but they may be related to host immunological defences, host genetic factors, environmental factors, such as food and salt intake, and/or to the bacterial virulence factors.

Gastric epithelial cell injury is caused by a vacuolating cytotoxin, encoded by the vacA gene, which induces host cell vacuolation and, finally, cell death. The vacA signal (s) region encodes the signal peptide and the N-terminus of the processed vacA toxin: the vacA s1 genotype is fully active but the type 2 genotype has a short N-terminus extension that blocks vacuole formation [10]. On the other hand, the vacA middle (m) region encodes part of the 55-KDa subunit located in the C-terminal. The vacA m region also has two genotypes (m1 and m2), and the m1 genotype causes stronger vacuolating activities than the m2 genotype [10]. These variations in the s and m regions give rise to four possible H. pylori genotypes: s1m1, s1m2, s2m1 and s2m2, although the s2m1 genotype is reported to be rare [10, 11]. The vacA s1 and m1 genotypes can be further classified into s1a, s1b and s1c; and m1a, m1b and m1c, respectively. In general, vacA s1m1 strains produce a large amount of toxin and induce higher vacuolating activity in gastric epithelial cells, s1m2 strains produce moderate amounts and s2m2 strains produce very little or no toxin [10, 12].

Recently, a third polymorphic determinant of vacuolating activity has been described as located between the s region and the m region; an intermediate (i) region [13]. The vacA i region encodes part of the p33 vacA subunit and classifies into two types, i1 (vacuolating) and i2 (non-vacuolating) [13]. Recent studies showed that gastric mucosa infected with the vacA i1 strains significantly increased inflammation cell infiltration and inflammation activity compared with that of the vacA i2 strains [14].

The vacA s1 and m1 genotypes have been reported to associate with H. pylori-related diseases, especially in Western countries, and vacA s2 and m2 strains are rarely associated with peptic ulcer and gastric cancer because of the low or non-vacuolating activity [10, 11, 15–20].

Although 17 studies based in the Middle East were reported to perform the genotyping of vacA s, m or i regions (Table 1) [13, 21–36], it is still unclear whether the vacA genotypes are associated with an increased risk for gastrointestinal disease in the Middle East or not because of the small sample size in each report. Therefore, this study was designed to elucidate the relationship between the vacA genotype and gastric cancer and peptic ulcer susceptibility in H. pylori-infected patients living in the Middle East by using systematic analyses that avoids type 2 error.

Table 1.

The genotypes of vacA s, m and i regions in studies used in the meta-analysis

| Area/ country | Authors | Year | Disease | Patients (n) | Mix (n) | No detected strain | Strain

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1 (n/%) | s2 (n/%) | m1 (n/%) | m2 (n/%) | i1 (n/%) | i2 (n/%) | |||||||

| Turkey | Aydin et al. [21] | 2004 | NUD, DU | 98s | 0 | 0 | 87 (88.8) | 11 (11.2) | 50 (51.0) | 48 (49.0) | NA | NA |

| Turkey | Saribasak et al. [22] | 2004 | NUD, PU, GC | 65 | 29m | 1 | 55 (94.8) | 3 (5.2%) | 8 (22.2) | 28 (77.8) | NA | NA |

| Turkey | Salih et al. [23] | 2005 | NUD, DU | 21 | 0 | 3ND | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | NA | NA |

| Turkey | Erzin et al. [24] | 2006 | NUD, PU, GC | 91 | 0 | 0 | 81a (89.0) | 10 (11.0) | 38 (41.8) | 53 (58.2) | NA | NA |

| Turkey | Caner et al. [25] | 2007 | NUD, DU | 46 | 0 | 0 | 41 (89.1) | 5 (10.9) | 11 (23.9) | 35 (76.1) | NA | NA |

| Turkey | Bolek et al. [26] | 2007 | NUD, PU | 44 | 0 | 0 | 41 (93.2) | 3 (6.8) | 24 (54.5) | 20 (45.5) | NA | NA |

| Turkey | Umit et al. [27] | 2008 | NA | 57 | 7m | 2 | 32 (64.0) | 18 (36.0) | 23 (43.4) | 30 (56.4) | NA | NA |

| Jordan | Nimri et al. [28] | 2006 | NA | 110 | 0 | 63ND | 34 (45.3) | 41 (54.7) | 23 (48.9) | 24 (51.1) | NA | NA |

| Iran | Mohammadi et al. [29] | 2003 | NUD, DU | 132 | 0 | 19 | 78b (69.0) | 35 (31.0) | 39 (34.5) | 74 (65.5) | NA | NA |

| Iran | Siavoshi et al. [30] | 2005 | NUD, PU, GC | 137 | 13 | 71 | 48 (90.6) | 5 (9.4) | 12 (22.6) | 41 (77.4) | NA | NA |

| Iran | Kamali-Sarvestani et al. [31] | 2006 | NUD, PU, GC | 298 | 0 | 34 | 191c (72.3) | 73 (27.7) | 81 (30.7) | 183 (69.3) | NA | NA |

| Iran | Rhead et al. [13] | 2007 | NUD, GC | 75 | 2 | 2 | 57 (80.3) | 14 (19.7) | 31 (43.7) | 40 (56.3) | 30d (51.7) | 28 (48.3) |

| Iran | Jafari et al. [32] | 2008 | NUD, PU, GC | 96 | 0 | 7 | 62 (69.7) | 27 (30.3) | 30 (33.7) | 59 (66.3) | NA | NA |

| Iran | Hussein et al. [33] | 2008 | NA | 59 | 7 | 0 | 36 (69.2) | 16 (30.8) | 16 (30.8) | 36 (69.2) | 19 (36.5) | 33 (63.5) |

| Iran | Hussein et al. [33] | 2008 | NUD, PU | 49 | 14 | 19 | 31 (88.6) | 4 (11.4) | 9 (25.7) | 26 (74.3) | 10d (28.5) | 25 (71.5) |

| Saudi Arabia | Momenah et al. [34] | 2006 | NUD, PU | 103 | 0 | 0 | 60 (58.3) | 43 (41.7) | 13 (12.6) | 90 (87.4) | NA | NA |

| Kuwait | Al Qabandi et al. [35] | 2005 | NA | 67 | 8 | 3 | 26 (46.4) | 30 (53.6) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Israel | Benenson et al. [36] | 2002 | NA | 98 | 0 | 11 | 23 (26.4) | 64 (73.6) | 7 (8.0) | 80 (92.0) | NA | NA |

NA = no data associating H. pylori disease development and vacA polymorphism; s = the use of single colonies [21] and the remaining studies refer to the use of gastric biopsy sample, paraffin-embedded biopsy sample and pool of cultured colonies

When patients were determined to be infected with multiple different H. pylori strains, each H. pylori strain was analysed as a different H. pylori genotype (m = mixed strains) [22, 27]. ND means no detailed information of H. pylori strain, whereas only vacA s or m region was detected [23, 28]. The study of Rhead et al. [13] had 15 i1 and i2 mixed strains. Therefore, these reports do not match with the patient number and strain number (H. pylori genotype number)

GC = gastric cancer; NA = not available; NUD = non-ulcer dyspepsia (gastritis alone without peptic ulcer and gastric cancer); PU = peptic ulcer (gastric ulcer and/or duodenal ulcer)

P < 0.05 (significantly increased risk of gastric cancer and duodenal ulcer developments when it was the vacAs1a genotype);

P < 0.05 (significantly increased risk of peptic ulcer when it was the vacA s1m2 genotype);

P < 0.05 (significantly increased risk of peptic ulcer when it was the vacA s1m1 genotype);

P < 0.05(significantly increased risk of peptic ulcer or gastric cancer when it was the vacA i1 genotype)

Materials and methods

Study selection

Previous publications measuring the genotypes of the vacA s, m or i regions in H. pylori strains isolated in the Middle East were enrolled in this study. Some North-African countries such as Egypt are also included in the Middle East; however, since the relationship between the vacA genotypes and clinical outcomes in African countries had been meta-analysed previously [37], we excluded the countries in this study. All eligible studies were identified by searching the PubMed database for manuscripts written in English and published before October 2008 using the following search criterion: “vacA or vacuolating cytotoxin” and “Helicobacter or pylori” and “genotypes”. The references cited in the enrolled manuscripts were also screened by the same criteria. Manuscripts that did not provide detailed genotype information were excluded. We conducted a meta-analysis to determine the association of the vacA s-, m- and i-region genotypes with the risk of developing gastrointestinal diseases.

Data analysis

In cases where patients were infected with multiple H. pylori strains, each strain was analysed separately [22, 27]. Since some studies did not measure all parameters simultaneously (vacA s-, m- and i-region genotypes, s- and m-region combined genotypes and cagA status), the patient number and strain number (H. pylori genotype number) did not match in the following analyses.

Statistical differences in the frequencies of vacA s-, m-and i-region genotypes among the individual countries were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Chi-square test. The effects of vacA s-, m- and i-region genotypes on the risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer development were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) with reference to non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD) subjects with H. pylori infection. NUD was defined as histological and/or endoscopical gastritis with no peptic ulcers or gastric cancer. Of those, six studies [22, 23, 25, 26, 31, 34] used control patients as ‘gastritis’, six studies [13, 21, 24, 29, 30, 32] used ‘NUD’ as controls and one study in Iraqi [33] used ‘non-ulcer disease’ as controls; therefore, we regarded the control group as ‘NUD’ in this study. All P-values were two-sided and P-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Included studies

Twenty studies investigating the Middle-Eastern population were found within our search criteria, and a report from Hussein et al. included two populations, Iranian and Iraqi [33]. Two studies from Farshad et al. [38] and Bulent et al. [39] did not provide detailed vacA genotype information and were excluded. Finally, a total of 17 studies with 1,646 patients were considered for the meta-analysis (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Summary of vacA s- and m-region genotypes in different countries

| Paper (n) | Patient (n) | Strain

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1 (n/%) | s1a (n/%) | s1b (n/%) s1c (n/%) | s2 (n/%) | m1 (n/%) | m2 (n/%) | s1m1 (n/%) | s1m2 (n/%) | s2m1 (n/%) | s2m2 (n/%) | i1 (n/%) | i2 (n/%) | ||||

| North Middle East | |||||||||||||||

| Turkey | 7 | 422 | 357 (87.7) | 237 (97.9) | 5 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 50 (12.3) | 166 (43.0) | 220 (57.0) | 122 (43.7) | 128 (45.9) | 1 (0.4) | 28 (10.0) | NA | NA |

| Iran | 6 | 797 | 476 (73.7) | NA | NA | NA | 170 (26.3) | 209 (32.6) | 433 (67.4) | 194 (30.2) | 278 (43.3) | 15 (2.3) | 155 (24.1) | 49 (44.5) | 61 (55.5) |

| Iraq | 1 | 49 | 31 (88.6) | NA | NA | NA | 4 (11.4) | 9 (25.7) | 26 (74.3) | 9 (25.7) | 22 (62.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (11.4) | 10 (28.6) | 25 (71.4) |

| Sub-total | 14 | 1,268 | 864 (79.4) | 237 (97.9) | 5 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 224 (20.6) | 384 (36.1) | 679 (63.9) | 325 (34.0) | 428 (44.8) | 16 (1.7) | 187 (19.5) | 59 (40.7) | 86 (59.3) |

| South Middle East | |||||||||||||||

| Jordan | 1 | 110 | 34 (45.3) | NA | NA | NA | 41 (54.7) | 23 (48.9) | 24 (51.1) | 12 (46.2) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 12 (46.2) | NA | NA |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 103 | 60 (58.3) | NA | NA | NA | 43 (41.7) | 13 (12.6) | 90 (87.4) | 13 (12.6) | 47 (45.6) | 0 (0) | 43 (41.7) | NA | NA |

| Kuwait | 1 | 67 | 26 (46.4) | NA | NA | NA | 30 (53.6) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Israel | 1 | 98 | 23 (26.4) | NA | NA | NA | 64 (73.6) | 7 (8.0) | 80 (92.0) | 7 (8.0) | 16 (18.4) | 0 (0) | 64 (73.6) | NA | NA |

| Sub-total | 4 | 378 | 143 (44.5) | NA | NA | NA | 178 (55.5) | 43 (18.1) | 194 (81.9) | 32 (14.8) | 65 (30.1) | 0 (0) | 119 (55.1) | NA | NA |

| Total | 17 | 1,646 | 1,007* (71.5) | 237 (97.9) | 5 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 402 (28.5) | 427a (32.8) | 873 (67.2) | 357a (30.5) | 493 (42.1) | 16 (1.4) | 306 (26.1) | 59 (40.7) | 86 (59.3) |

Hussein et al. [33] reported two populations, Iranian and Iraqi, and, therefore, a number of entries had one study taken off. When patients were determined to be infected with multiple different H. pylori strains, each H. pylori strain was analysed as a different H. pylori genotype. Therefore, the reports do not match with the patient number and strain number (H. pylori genotype number)

P < 0.05 (significant differences among different countries in the same area)

NA = not available

Prevalence of vacA s-, m- and i-region genotypes

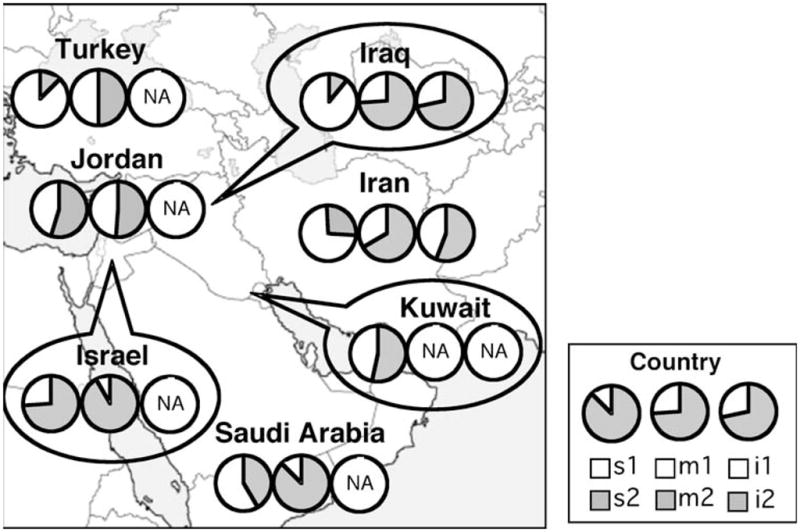

The prevalence of vacA s-, m- and i-region and vacA s/m combination genotypes differed significantly among the various countries within the Middle East (P<0.001) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The studies using strains isolated in the northern part of the Middle East, such as Turkey, Iran and Iraq, had a high prevalence of vacA s1 genotype of more than 70%, whereas strains from the southern part, such as Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Israel, had a low prevalence of less than 60% (Table 2). The prevalence of vacA s1 genotype in the northern part was 79.4%, which was significantly higher than that in the southern parts (44.5%, P<0.001) (Table 2). Although there were only four studies investigating the subtyping of the vacA s1 genotypes, and all were from Turkey [21–24], 97.9% of the s1 genotypes was of the s1a subtype. There was no vacA s1c subtype in strains from the Middle East that were reported to be specific for East Asian strains [11]. Most of the Middle Eastern strains had frequencies of vacA m1 genotypes less than 50% and the prevalence of vacA m1 genotype in the northern part was 36.1%, which was significantly higher than that in the southern parts (18.1%, P<0.001) (Table 2). Especially in Israel, the prevalence of vacA m1 genotype was only 8.0% [36]. In the combination of vacA s- and m-region genotypes, the predominant genotype was vacA s1m2 (42.1%), followed by s1m1 (30.5%) and s2m2 (26.1%). The frequency of the vacA s2m1 genotype was only 1.4% in our analyses, which was in agreement with most of the previous studies in other regions [10, 37]. No previous studies had examined the subtypes of m1 in the Middle East.

Fig. 1.

The proportions of vacA s, m and i genotypes in different Middle Eastern populations; the frequencies of vacA s, m and i genotypes significantly differed among the individual countries of the Middle East

Although there were data of vacA i-region genotypes in only the Iranian and Iraqi populations [13, 33], the prevalence of the vacA i1 and i2 genotype had no significant difference between Iranian and Iraqi strains (P=0.10) (Tables 1 and 2).

The percentage of patients infected with more than two different vacA genotypes of H. pylori and non-genotypeable strains (including vacA-negative strains) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was 4.9% (80/1,646) and 13.1% (216/ 1,648), respectively. The rate of non-genotyped strains was relatively higher, especially in reports from Siavoshi et al. (51.8%, 71/137) [30] and Nimri et al. (57.3%, 63/110) [28], than previous reports [11, 37, 40].

Risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer development associated with the vacA s, m and i genotypes

Of 17 studies, five did not demonstrate the association with gastroduodenal diseases and vacA s and m genotypes [27, 28, 33, 35, 36]. Although two studies showed only an association with gastroduodenal diseases and vacA i-region genotype [13, 33], there was no detailed data of each patient in the Iranian of study of Hussein et al. [33].

The vacA s1 genotype was linked to an increased risk in four of 11 (36.3%) studies for peptic ulcers [24, 26, 29, 31] and two of six (33.3%) studies for gastric cancer [13, 24], and especially Erzin et al. [24] reported its significance in the vacA s1a genotype. The vacA m1 genotype was linked to an increased risk in two of 11 (18.1%) studies for peptic ulcers [23, 34] and two of six (33.3%) studies for gastric cancer [13, 31]. One each (10%) of ten studies demonstrated significantly increased risk of peptic ulcers with the vacA s1m1 [31] and s1m2 [29] genotype, respectively (Tables 1 and 3).

Table 3.

Summary of vacA s, m and i genotypes in relation to peptic ulcer and gastric cancer risk

| Authors | Country | Non-ulcer dyspepsia

|

Peptic ulcer

|

Gastric cancer

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1 | m1 | i1 | s1 | m1 | i1 | s1 | m1 | i1 | ||

| Aydin et al. [21] | Turkey | 46/51 (90.2) | 28/51 (54.9) | 41/47 (87.2) | 22/47 (46.8) | |||||

| Saribasak et al. [22] | Turkey | 19/20 (95.0) | 2/14 (14.3) | 28/29 (96.6) | 3/15 (20.0) | 8/9 (88.9) | 3/7 (42.9) | |||

| Salih et al. [23] | Turkey | 7/7 (100) | 1/6 (16.7) | 13/13 (100) | 11/12 b (91.7) | |||||

| Erzin et al. [24] | Turkey | 23/30 (76.7) | 10/30 (33.3) | 28/28a (100) | 15/28 (53.6) | 30/33a (90.9) | 13/33 (39.4) | |||

| Caner et al. [25] | Turkey | 15/16 (93.8) | 4/16 (25.0) | 26/30 (86.7) | 7/30 (23.3) | |||||

| Bolek et al. [26] | Turkey | 5/7 (71.4) | 0/7 (0) | 36/37b (97.3) | 24/37 (64.9) | |||||

| Mohammadi et al. [29] | Iran | 58/90 (64.4) | 33/90 (36.7) | 20/23b (87.0) | 6/23 (26.1) | |||||

| Siavoshi et al. [30] | Iran | 30/33 (90.9%) | 6/33 (18.2) | 13/15 (86.7) | 5/15 (33.3) | 5/5 (100) | 1/5 (20.0) | |||

| Kamali-Sarvestani et al. [31] | Iran | 122/181 (67.4) | 48/181 (26.5) | 54/65b (83.1) | 21/65 (32.3) | 15/18 (83.3) | 12/18 b (66.7) | |||

| Rhead et al. [13] | Iran | 30/42 (71.4) | 13/42 (31.0) | 18/42 (42.9) | 29/31a (93.5) | 19/31a (61.3) | 27/31a (87.1) | |||

| Jafari et al. [32] | Iran | 50/69 (72.5) | 26/69 (37.8) | 9/17 (52.9) | 4/17 (23.5) | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 (0) | |||

| Hussein et al. [33] | Iraq | 4/29 (13.8) | 4/5a (80.0) | |||||||

| Momenah et al. [34] | Saudi | 53/96 (55.2.5) | 8/96 (8.3) | 7/7 (100) | 5/7b (71.4) | |||||

| Total | 458/642 (71.3) | 179/645 (27.8) | 22/71 (31.0) | 275/311a (88.4) | 123/296a (41.6) | 4/5 (80.0) | 90/99a (90.9) | 48/97a (49.5) | 27/31a (87.1) | |

P < 0.05 (vs. significant prevalence rate of gastritis patients by study);

P < 0.05 (vs. significant prevalence rate of gastritis patients by our analysis)

Rhead et al. [13] reported that the vacA i1 genotype was significantly linked to gastric cancer in the Iranian population. Hussein et al. [33] reported that gastric ulcer development in the Iraqi population was associated with the vacA i1 genotype, but the same did not hold true for the Iranian population.

The frequency of vacA s1 (88.4%) and m1 (41.6%) in H. pylori-infected patients with peptic ulcers was significantly higher than that with gastritis alone (71.3% and 27.8%, respectively) (Table 3). There was a tendency of association with peptic ulcer and i1 genotypes (80.0% vs. 31.0% for NUD patients); this was not significant because of the low sample power. In the Middle East, the vacA s1, m1 and s1m1 genotypes significantly increased the risk of peptic ulcers (OR: 3.07, 95% CI: 2.08–4.52 for s1; 1.81, 1.36–2.42 for m1; 3.52, 2.24–5.54 for s1m1) (Table 4). The frequencies of vacA s1, m1 and i1 genotypes in patients with gastric cancer were 90.9%, 49.5% and 87.1%, respectively, which were significantly higher than the frequency of gastritis alone (71.3%, 27.8% and 31.0%, respectively) (P< 0.01 for each). The risk of developing gastric cancer was significantly increased with the vacA s1 (OR: 4.02, 95% CI: 1.98–8.14), m1 (2.50, 1.62–3.85), s1m1 (5.27, 1.97–14.1) and i1 (15.03, 4.69–48.17) genotypes compared to patients with gastritis alone (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 4.

The risk of gastrointestinal disease development in relation to H. pylori virulence factors

| Diseases | Factor | n | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptic ulcer, N=311 | s1 | 275 | 3.07 | 2.08–4.52 | < 0.01 |

| m1 | 123 | 1.81 | 1.36–2.42 | 0.01 | |

| s1m1 | 98 | 3.52 | 2.24–5.54 | < 0.01 | |

| s1m2 | 125 | 2.51 | 1.63–3.89 | < 0.01 | |

| i1 | 4 | 8.91 | 0.94–84.4 | 0.06 | |

| Gastric cancer, N=99 | s1 | 90 | 4.02 | 1.98–8.14 | < 0.01 |

| m1 | 48 | 2.50 | 1.62–3.85 | < 0.01 | |

| s1m1 | 25 | 5.27 | 1.97–14.11 | < 0.01 | |

| s1m2 | 36 | 3.55 | 1.34–9.38 | 0.01 | |

| i1 | 27 | 15.03 | 4.69–48.17 | <0.01 |

The association between cagA status and vacA genotypes in the Middle Eastern population

There were seven studies that reported an association between cagA status and vacA genotypes [13, 24, 26, 30, 32, 33, 36]. The cagA status of H. pylori strains was strongly associated with the vacA s1, m1 and i1 genotypes (P<0.01), and the prevalence of vacA s1, m1, and s1m1 genotypes significantly differed among patients with/without cagA-positive strains (P<0.01) (Table 5). The prevalence of vacA s1 and cagA-negative strains was 47.1%, which was relatively higher than previous reports of other areas. In cagA-negative strains, most of the vacA genotypes were i2 genotypes (90%) (Table 5).

Table 5.

The association of cagA status and vacA genotypes

| cagA status | s1 (n/%) | s2 (n/%) | m1 (n/%) | m2 (n/%) | s1m1 (n/%) | s1m2 (n/%) | s2m1 (n/%) | s2m2 (n/%) | i1 (n/%) | i2 (n/%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 255 (86.4) | 40 (13.6) | 62 (46.3) | 72 (53.7) | 60 (48.0) | 57 (45.6) | 2 (1.6) | 6 (4.8) | 29 (60.4) | 19 (39.6) |

| Negative | 89 (47.1) | 100 (52.9) | 12 (16.7) | 60 (83.3) | 10 (15.8) | 43 (68.3) | 2 (3.2) | 8 (12.7) | 1 (10.0) | 9 (90.0) |

In seven studies which reported the association of cagA status and vacA genotypes [13, 24, 26, 30, 32, 33, 36], the cagA status was associated with increased risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer development (Tables 6 and 7). In the Middle East, the cagA status significantly increased the risk of peptic ulcers (OR: 1.82, 95% CI: 1.26–7.04) and gastric cancer (3.51, 1.75–7.04) (Table 7). However, in the Iranian population, there were no significant relationships between cagA status and diseases risks.

Table 6.

The association between gastroduodenal diseases and cagA status

| Authors | Year | Country | Total | NUD | PU | GC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erzin et al. [24] | 2006 | Turkey | 67/91 (74%) | 15/30 (50%) | 24/28 (86%) | 28/33(85%) |

| Bolek et al. [26] | 2007 | Turkey | 43/52 (83%) | 7/10 (70%) | 36/42 (86%) | |

| Benenson et al. [36] | 2002 | Israel | 24/97 (25%) | 22/86 (26%) | 2/11 (18%) | |

| Siavoshi et al. [30] | 2005 | Iran | 61/136 (45%) | 28/61 (46%) | 21/57 (37%) | 12/18 (67%) |

| Jafari et al. [32] | 2008 | Iran | 73/96 (76%) | 55/74 (74%) | 15/19 (79%) | 3/3 (100%) |

| Rhead et al. [13] | 2007 | Iran | 63/73 (86%) | |||

| Hussein et al. [33] | 2008 | Iran | 45/59 (76%) | 32/42 (76%) | 13/17 (76%) | |

| Iraq | 35/49 (71%) | 16/29 (55%) | 19/20 (95%) | |||

| Total | 411/653 (63%) | 175/332 (53%) | 130/194 (67%) | 43/54 (80%) |

NUD = non-ulcer dyspepsia; PU = peptic ulcer; GC = gastric cancer

Table 7.

The risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer development in relation to cagA status

| Diseases | N | n | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptic ulcer | 194 | 130 | 1.82 | 1.26–2.64 | 0.01 |

| Gastric cancer | 54 | 43 | 3.51 | 1.75–7.04 | < 0.01 |

Discussion

Most gastric cancer patients were at stages III and IV of the OLGA system with severe mucosal atrophy in the whole stomach [41, 42]. More virulent genotypes were connected to gastric epithelial damage, including gastric mucosal atrophy, in H. pylori-infected patients [18]. In fact, H. pylori strains with the vacA s1, m1 and i1 genotypes and cagA-positive strains have been linked to higher degrees of inflammation cell infiltration compared to that with vacA s2, m2 and i2 genotypes and cagA-negative strains [43, 44]. However, two-thirds of previous reports carried out in the Middle East had shown no significant relationship between vacA genotypes and gastrointestinal diseases because of the low sample power (only one study with more than 100 NUD patients and more than 50 disease patients [31]); it was unclear whether the connection between virulence factors and disease development has an association (Table 1) [13, 21–36]. As summarized in Table 1, the sample number of each study was small and insufficient to clarify the significance of the relationship between virulence factors of H. pylori and gastroduodenal diseases. Therefore, by meta-analysis using many patients, the association between vacA genotypes and diseases risk in the Middle East needs to be clarified. We found that the vacA s1 and m1 genotypes increased the risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer by 2–5 times in these countries, as well as in developed Western countries and Latin America [11, 37, 40, 45, 46]. Therefore, we concluded that the H. pylori virulence factor, vacA, causes enhanced gastric mucosal inflammation and damage, leading to gastric cancer and peptic ulcer development in the Middle East.

In the Middle East, the frequencies of the vacA s genotype significantly differed between the northern part (Turkey, Iran and Iraq) and the southern part (Kuwait, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Israel). The higher detection rate of the vacA s1 genotype was revealed from South Asian countries, such as India and Bangladesh, to East Europe throughout the northern part of the Middle East, as observed in this study [47]. Moreover, 97.9% of the vacA s1 genotype was of s1a sub-type in four Turkey studies which performed the sub-typing of vacA s1 [21–24]. This pattern of which vacA s1a sub-type was the dominant allele in Turkey was the same as the European type, and the population that lived in a part of the Middle East, including Turkey, might correlate with the European population. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia in middle part of the Middle East was liable to be equally infected with the vacA s1 and s2 alleles, whereas most of the Israeli population near African Arabs had the vacA s2 genotype. Van Doorn et al. [20] reported that the prevalence of the vacA s1 and m1 genotypes in strains from Egypt was 42.9% and 14.3%, respectively. This finding suggested that the population which lived in the southern part of the Middle Eastern population near African Arabs might correlate culturally with African countries and not the north side of the Middle Eastern population.

Gastric cancer is uncommon in the Middle East, despite high levels of H. pylori infection [4, 5], as observed in so-called ‘African enigma’ [48]. This phenomenon might explain that the widespread prevalence of weakly cytotoxic strains may be the reason for the low frequency of H. pylori-associated diseases in African populations [37]. In this study, the prevalence of the vacA m1 region in the Middle Eastern population and the s1 region in its southern part was lower than in the East Asian and Latin American populations with a higher risk of gastric carcinogenesis [11, 37]. Therefore, it might be explained that the lower prevalence of higher virulent strains may be the reason for the low frequency of gastric cancer, especially in the southern part of the Middle East. However, the vacA s1 and m1 genotypes significantly increased the risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer development. Therefore, the bacterial factors are important in determining gastric cancer risk.

Recently, a third polymorphic determinant of vacuolating activity was identified as the vacA i region [13]. Although in East and Southeast Asia the vacA s, m and i combined genotypes did not add any advantage as disease-determinant markers to s- and m-region genotyping [49], vacA i1 genotypes were associated with gastric cancer in the Iranian and Italian populations and gastric ulcer in the Iraqi and Italian populations [13, 14, 33]. Hussein et al. [33] reported that 80% (4/5) of H. pylori strains isolated from gastric ulcer Iraqi patients were vacA i1 genotype, which was significantly higher than 13% (4/29) from non-ulcer patients, but not in the Iranian population. Despite the geographical proximity of Iraq and Iran, the incidence of gastric cancer differs hugely between these countries; in Iran, it ranges from 38–69/100,000 population [50, 51], whereas in Iraq, the incidence is 5/100,000 population (http://www-dep.iarc.fr/). This difference in the vacA i region of the H. pylori strains between two countries may partially explain the difference between gastric cancer incidence, because the vacA s and m genotypes were almost equal between countries. Therefore, the vacA i genotyping might be a better predictor of H. pylori carcinogenic potential than previous s- and m-region genotyping in the Middle East and South Europe. However, because the data of the vacA i-region genotype in gastroduodenal disease patients was insufficient for analysing the risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer developments with sufficient sample power, further reports would be required.

Two reports from Siavoshi et al. (51.8%) [30], using DNA extracted from multiple colonies of H. pylori, and Nimri et al. (57.3%) [28], using DNA extracted directly from gastric biopsy samples, had higher rates of non-genotyped strains than previous reports, whereas the PCR condition is acceptable [11, 37, 40]. Nimri et al. [28] used primer pairs of VA1-F and VA1-R for the vacA s region and VAG-F and VAG-R for the m-region, as previously reported [10, 19], and Siavoshi et al. [30] used primer pairs of VA1-F and VA1-R for the vacA s region [10, 19] and VA3-F/VA3-R for the m1 region and VA4-F/VA4-R for the m2 region as originally. Most of the studies using the VA1-F/VA1-R pairs for the vacA s region and VAG-F/ VAG-R for the m region were reported to be able to detect more than 95% of samples in the Western and Asian populations [10, 19]. Although detailed reasoning was unclear, it might have been caused by technical problems, including failure of the primer setting. There was also the possibility that half of the H. pylori strains had specific sequences in parts of primers previously reported and that H. pylori with a third genotype, such as s2 or m3, consisted in the Middle East, especially in the limited area of Iran and Jordan. Further studies will be necessary to clarify this by sequence analysis.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the vacA s1 and m1 genotypes increase the risks of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer in the Middle East, and that the prevalence of specific vacA s and m genotypes varies significantly among the individual countries. Genotype testing of vacA will be useful in screening individuals for risk factors associated with gastric cancer and peptic ulcer development not only in Western countries, but also in the Middle East as well. Although it is still possible that the vacA i1 genotypes are risk factors for diseases development, the present data is insufficient to evaluate the effect of the vacA virulence factor in H. pylori-related diseases. Therefore, the clinical usefulness of this genotyping test must be evaluated in future studies under the appropriate study design using many individuals with several vacA genotypes. However, it might be difficult to explain the ‘Middle Eastern enigma’ by only the genotyping of vacA genotypes, and, therefore, we had to evaluate the pathogenesis of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer by combination analysis of bacterial factors, the host’s genetic factors and environmental factors.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01 DK62813 (to Y.Y.).

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest exist in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

M. Sugimoto, Department of Medicine, Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, 2002 Holcombe Blvd., (111D) Rm 3A-320, Houston, TX 77030, USA

M. R. Zali, Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, Research Center for Gastroenterology and Liver Disease, Shaheed Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran

Y. Yamaoka, Email: yyamaoka@bcm.tmc.edu, yyamaoka@med.oita-u.ac.jp, Department of Medicine, Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, 2002 Holcombe Blvd., (111D) Rm 3A-320, Houston, TX 77030, USA. Department of Environmental and Preventive Medicine, Oita University Faculty of Medicine, Yufu, Japan

References

- 1.Perez-Perez GI, Taylor DN, Bodhidatta L, Wongsrichanalai J, Baze WB, Dunn BE, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infections in Thailand. J Infect Dis. 1990;161(6):1237–1241. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocha GA, Queiroz DM, Mendes EN, Oliveira AM, Moura SB, Barbosa MT, et al. Indirect immunofluorescence determination of the frequency of anti-H. pylori antibodies in Brazilian blood donors. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1992;25(7):683–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souto FJ, Fontes CJ, Rocha GA, de Oliveira AM, Mendes EN, Queiroz DM. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in a rural area of the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1998;93(2):171–174. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761998000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandikci MU, Doran F, Koksal F, Sandikci S, Uluhan R, Varinli S, et al. Helicobacter pylori prevalence in a routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy population. Br J Clin Pract. 1993;47(4):187–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massarrat S, Saberi-Firoozi M, Soleimani A, Himmelmann GW, Hitzges M, Keshavarz H. Peptic ulcer disease, irritable bowel syndrome and constipation in two populations in Iran. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7(5):427–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(11):784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins RJ, Girardi LS, Turney EA. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori eradication and reduced duodenal and gastric ulcer recurrence: a review. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(4):1244–1252. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, de Boni M, Spencer J, Isaacson PG. Antibiotic treatment for low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Lancet. 1994;343(8911):1503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92613-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, Inoue K, Uemura N, Okamoto S, et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):392–397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atherton JC, Cao P, Peek RM, Jr, Tummuru MK, Blaser MJ, Cover TL. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(30):17771–17777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaoka Y, Orito E, Mizokami M, Gutierrez O, Saitou N, Kodama T, et al. Helicobacter pylori in North and South America before Columbus. FEBS Lett. 2002;517(1–3):180–184. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Letley DP, Atherton JC. Natural diversity in the N terminus of the mature vacuolating cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori determines cytotoxin activity. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(11):3278–3280. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.11.3278-3280.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhead JL, Letley DP, Mohammadi M, Hussein N, Mohagheghi MA, Eshagh Hosseini M, et al. A new Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin determinant, the intermediate region, is associated with gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(3):926–936. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basso D, Zambon CF, Letley DP, Stranges A, Marchet A, Rhead JL, et al. Clinical relevance of Helicobacter pylori cagA and vacA gene polymorphisms. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):91–99. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kidd M, Lastovica AJ, Atherton JC, Louw JA. Heterogeneity in the Helicobacter pylori vacA and cagA genes: association with gastroduodenal disease in South Africa? Gut. 1999;45(4):499–502. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.4.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miehlke S, Kirsch C, Agha-Amiri K, Günther T, Lehn N, Malfertheiner P, et al. The Helicobacter pylori vacA s1, m1 genotype and cagA is associated with gastric carcinoma in Germany. Int J Cancer. 2000;87(3):322–327. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215 (20000801)87:3<322::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figueiredo C, Van Doorn LJ, Nogueira C, Soares JM, Pinho C, Figueira P, et al. Helicobacter pylori genotypes are associated with clinical outcome in Portuguese patients and show a high prevalence of infections with multiple strains. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(2):128–135. doi: 10.1080/003655 20120921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atherton JC, Peek RM, Jr, Tham KT, Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Clinical and pathological importance of heterogeneity in vacA, the vacuolating cytotoxin gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(1):92–99. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(97)70223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Gutierrez O, Kim JG, Kashima K, Graham DY. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori iceA, cagA, and vacA status and clinical outcome: studies in four different countries. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(7):2274–2279. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2274-2279.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Mégraud F, Pena S, Midolo P, Queiroz DM, et al. Geographic distribution of vacA allelic types of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(4):823–830. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70065-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aydin F, Kaklikkaya N, Ozgur O, Cubukcu K, Kilic AO, Tosun I, et al. Distribution of vacA alleles and cagA status of Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease and non-ulcer dyspepsia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(12):1102–1104. doi: 10.1111/ j.1469-0691.2004.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saribasak H, Salih BA, Yamaoka Y, Sander E. Analysis of Helicobacter pylori genotypes and correlation with clinical outcome in Turkey. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(4):1648–1651. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.4.1648-1651.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salih BA, Abasiyanik MF, Saribasak H, Huten O, Sander E. A follow-up study on the effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the severity of gastric histology. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(8):1517–1522. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erzin Y, Koksal V, Altun S, Dobrucali A, Aslan M, Erdamar S, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori vacA, cagA, cagA, cagE, iceA, babA2 genotypes and correlation with clinical outcome in Turkish patients with dyspepsia. Helicobacter. 2006;11(6):574–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2006.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caner V, Yilmaz M, Yonetci N, Zencir S, Karagenc N, Kaleli I, et al. H pylori iceA alleles are disease-specific virulence factors. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(18):2581–2585. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i18.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolek BK, Salih BA, Sander E. Genotyping of Helicobacter pylori strains from gastric biopsies by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. How advantageous is it? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;58(1):67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umit H, Tezel A, Bukavaz S, Unsal G, Otkun M, Soylu AR, et al. The relationship between virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori and severity of gastritis in infected patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:103–110. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0316-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nimri LF, Matalka I, Bani Hani K, Ibrahim M. Helicobacter pylori genotypes identified in gastric biopsy specimens from Jordanian patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:27. doi: 10.1186/ 1471-230X-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammadi M, Oghalaie A, Mohajerani N, Massarrat S, Nasiri M, Bennedsen M, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin and its allelic mosaicism as a predictive marker for Iranian dyspeptic patients. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2003;96(1):3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siavoshi F, Malekzadeh R, Daneshmand M, Ashktorab H. Helicobacter pylori endemic and gastric disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(11):2075–2080. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamali-Sarvestani E, Bazargani A, Masoudian M, Lankarani K, Taghavi AR, Saberifiroozi M. Association of H pylori cagA and vacA genotypes and IL-8 gene polymorphisms with clinical outcome of infection in Iranian patients with gastrointestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(32):5205–5210. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i32.5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jafari F, Shokrzadeh L, Dabiri H, Baghaei K, Yamaoka Y, Zojaji H, et al. vacA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori in relation to cagA status and clinical outcomes in Iranian populations. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2008;61(4):290–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hussein NR, Mohammadi M, Talebkhan Y, Doraghi M, Letley DP, Muhammad MK, et al. Differences in virulence markers between Helicobacter pylori strains from Iraq and those from Iran: potential importance of regional differences in H.pylori-associated disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(5):1774–1779. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01737-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Momenah AM, Tayeb MT. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori vacA genotypes status and risk of peptic ulcer in Saudi patients. Saudi Med J. 2006;27(6):804–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al Qabandi A, Mustafa AS, Siddique I, Khajah AK, Madda JP, Junaid TA. Distribution of vacA and cagA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori in Kuwait. Acta Trop. 2005;93(3):283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benenson S, Halle D, Rudensky B, Faber J, Schlesinger Y, Branski D, et al. Helicobacter pylori genotypes in Israeli children: the significance of geography. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35(5):680–684. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200211000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugimoto M, Yamaoka Y. The association of vacA genotype and Helicobacter pylori-related disease in Latin American and African populations. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02769.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farshad S, Japoni A, Alborzi A, Hosseini M. Restriction fragment length polymorphism of virulence genes cagA, vacA and ureAB of Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from Iranian patients with gastric ulcer and nonulcer disease. Saudi Med J. 2007;28(4):529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bulent K, Murat A, Esin A, Fatih K, MMMurat H, Hakan H, et al. Association of CagA and VacA presence with ulcer and non-ulcer dyspepsia in a Turkish population. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(7):1580–1583. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i7.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Sanna R, Plaisier A, Schneeberger P, de Boer W, et al. Clinical relevance of the cagA, vacA, and iceA status of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(1):58–66. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rugge M, Meggio A, Pennelli G, Piscioli F, Giacomelli L, De Pretis G, et al. Gastritis staging in clinical practice: the OLGA staging system. Gut. 2007;56(5):631–636. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.106666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rugge M, Correa P, Di Mario F, El-Omar E, Fiocca R, Geboes K, et al. OLGA staging for gastritis: a tutorial. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40(8):650–658. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nogueira C, Figueiredo C, Carneiro F, Gomes AT, Barreira R, Figueira P, et al. Helicobacter pylori genotypes may determine gastric histopathology. Am J Pathol. 2001;158(2):647–654. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64006-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martins LC, Corvelo TC, Demachki S, Araujo MT, Assumpção MB, Vilar SC, et al. Clinical and pathological importance of vacA allele heterogeneity and cagA status in peptic ulcer disease in patients from North Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100(8):875–881. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762005000800009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Sanna R, Blaser MJ, Quint WG. Distinct variants of Helicobacter pylori cagA are associated with vacA subtypes. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(7):2306–2311. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2306-2311.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Kashima K, Graham DY, Sepulveda AR. Variants of the 3′ region of the cagA gene in Helicobacter pylori isolates from patients with different H. pylori-associated diseases. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(8):2258–2263. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2258-2263.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chattopadhyay S, Datta S, Chowdhury A, Chowdhury S, Mukhopadhyay AK, Rajendran K, et al. Virulence genes in Helicobacter pylori strains from West Bengal residents with overt H.pylori-associated disease and healthy volunteers. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(7):2622–2625. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2622-2625.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holcombe C. Helicobacter pylori: the African enigma. Gut. 1992;33(4):429–431. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogiwara H, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. vacA i-region subtyping. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4):1267. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.062. author reply 1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadjadi A, Malekzadeh R, Derakhshan MH, Sepehr A, Nouraie M, Sotoudeh M, et al. Cancer occurrence in Ardabil: results of a population-based cancer registry from Iran. Int J Cancer. 2003;107(1):113–118. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sadjadi A, Nouraie M, Mohagheghi MA, Mousavi-Jarrahi A, Malekezadeh R, Parkin DM. Cancer occurrence in Iran in 2002, an international perspective. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2005;6 (3):359–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]