Summary

Chronic stress contributes to many neuropsychiatric disorders in which the HPA axis, cognition and neuro-immune activity are dysregulated. Patients with major depression, or healthy individuals subjected to acute stress, present elevated levels of circulating pro-inflammatory markers. Acute stress also activates pro-inflammatory signals in the periphery and in the brain of rodents. However, despite the clear relevance of chronic stress to human psychopathology, the effects of prolonged stress exposure on central immune activity and reactivity have not been well characterized. Our laboratory has previously shown that, in rats, chronic intermittent cold stress (CIC stress, 4 °C, 6h/day, 14 days) sensitizes the HPA response to a subsequent novel stressor, and produces deficits in a test of cognitive flexibility that is dependent upon prefrontal cortical function. We have hypothesized that CIC stress could potentially exert some of these effects by altering the neuro-immune status of the brain, leading to neuronal dysfunction. In this study, we have begun to address this question by determining whether previous exposure to CIC stress could alter the subsequent neuro-immune response to an acute immunological challenge (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) or an acute heterologous stressor (footshock). We examined the response of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL1β and IL6, the enzyme cyclooxygenase 2, and the chemokines, CXCL1 and MCP-1 in plasma, hypothalamus and prefrontal cortex. There was no effect of CIC stress on basal expression of these markers 24h after the termination of stress. However, CIC stress enhanced the acute induction of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL1β and particularly IL6, and the chemokines, CXCL1 and MCP-1, in plasma, hypothalamus and prefrontal cortex in response to LPS, and also sensitized the hypothalamic IL1β response to acute footshock. Thus, sensitization of acute pro-inflammatory responses in the brain could potentially mediate some of the CIC-dependent changes in HPA and cognitive function.

Keywords: Chronic stress, lipopolysaccharide, footshock, cytokines, prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus

1. Introduction

Activation or increased reactivity of the innate immune system is increasingly found to be associated with central nervous system (CNS) dysfunctions, such as neurodegeneration and age related cognitive decline (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2003), as well as mood and anxiety disorders (Maes et al., 1998; Dantzer et al., 2008b; Miller et al., 2009). Depressed patients often present with elevated basal plasma and CSF levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL1, IL2, IL6 and TNFα), which are released primarily by macrophages in the periphery and by microglia in the CNS (Miller et al., 2009). Persistent elevation of these signaling molecules leads to activation of NFκB-dependent arachidonic acid metabolism and nitrosative-oxidative pathways, with a resulting accumulation of toxic species and apoptotic cell death (Anisman, 2009). In addition to overt cell loss and neuronal degeneration, prolonged activation of pro-inflammatory pathways may also interfere directly with neuronal transmission thresholds (Kawasaki et al., 2008) and axonal growth (Gutierrez et al., 2008). Thus, increased pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling in the brain could potentially affect neural function in a variety of ways, thereby contributing to the variety of behavioral, cognitive, affective and endocrine dysregulation associated with depression and anxiety disorders.

Interleukin-6 (IL6) appears to be one of the most reliable markers of inflammation-associated mood and anxiety disorders (Miller et al., 2009). Basal levels of IL6 are often elevated in major depressive patients, and higher basal levels of IL6 predict poor outcome with antidepressant treatment (Lanquillon et al., 2000; Benedetti et al., 2002). In addition, stress-induced IL6 levels in blood monocytes are higher in individuals with major depression (Pace et al., 2006) or who have suffered childhood abuse (Carpenter et al., 2010) compared to healthy individuals. Finally, acute C-reactive protein and IL6 have been proposed as biomarkers for standardized tests of inflammation-dependent behavioral and mood changes associated with sickness responses and depression (Zorrilla et al., 2001; Dantzer et al., 2008a).

Stress often precipitates or exacerbates the symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders, and it can influence the immunological status of the organism. Exposure to acute stress elevates peripheral inflammatory markers both in healthy humans (Bierhaus et al., 2003) and in rodents (Deak et al., 2003; O'Connor et al., 2003). Moreover, acutely stressed animals respond to a peripheral immune challenge with an enhanced production of brain pro-inflammatory cytokines (Johnson et al., 2002), likely via microglial activation (Frank et al., 2007). However, not all stressors produce increased peripheral or central inflammatory responses (Goujon et al., 1995; Deak et al., 2003; Meltzer et al., 2004), and the mechanisms by which stress can affect immune status are not well characterized. In addition, despite evidence in humans linking long-term stress to elevated peripheral markers of inflammation, such as IL6 (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2008), very few animal models have investigated the influence of chronic stress on brain immune function. Given the clear etiological relevance of chronic stress to human psychopathology, and a general lack of information regarding its effects on pro-inflammatory responses, especially in the brain, we hypothesized that chronic, repeated stress can induce alterations in brain immune signaling that may lead to a sensitized response to subsequent novel stimuli, increasing acute stress reactivity and amplifying the release of pro-inflammatory signaling molecules, all of which may eventually result in compromised endocrine and cognitive function.

Our laboratory has shown that chronic intermittent cold (CIC) stress sensitizes the reactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to subsequent acute stressors (Pardon et al., 2003; Ma and Morilak, 2005). In addition, CIC stress induces a cognitive deficit in an animal test of cognitive flexibility, the attentional set-shifting test (AST), that is dependent on frontal cortical serotonergic function, and can be reversed with chronic SSRI treatment (Lapiz-Bluhm et al., 2009; Lapiz-Bluhm and Morilak, 2010). Therefore, besides having metabolic effects, CIC stress affects two dimensions of brain function (cognitive flexibility and stress hormone reactivity) that are also impaired in mood disorders. Thus, a possible mechanism for these effects is that CIC stress may affect the neuro-immunological status of the brain. In this study we began investigating this possibility by determining whether two weeks of CIC stress can affect expression levels of pro-inflammatory molecules in the rat hypothalamus and in the prefrontal cortex 24 h after the last cold exposure, at which time the HPA response to a novel acute stress has been shown to be sensitized (Ma and Morilak, 2005). It is also possible, however, that CIC stress, which is a relatively mild metabolic stressor, will not induce a full-blown inflammatory state, but may instead produce more subtle changes, similar to those seen for the HPA axis, for instance by altering the sensitivity of the immune system to subsequent novel challenges. Therefore, we examined how CIC stress affects pro-inflammatory immune responses to either an acute immune challenge (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) or a non-immune challenge (footshock). We also measured changes in systemic inflammatory responses and acute activation of the HPA axis following CIC stress. Portions of this work have been presented in abstract form (Donegan et al., 2010; Girotti et al., 2010).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, N=232) were used in these experiments. The rats, weighing approximately 220–240 g upon arrival, were group-housed (3 per cage) and maintained on a 12/12-hour light cycle (lights on at 0700h) with access to food and water ad libitum. Animals were allowed to acclimatize to the facility for a minimum of 4 days before any experimental procedures began. One day prior to beginning the cold stress treatment, the rats were individually housed. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and were consistent with NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23, revised 1978). All efforts were made to minimize unnecessary pain and distress, and the number of animals used.

2.2. Chronic Intermittent Cold (CIC) Stress

Animals were randomly assigned to CIC stress or control groups. Cold-stressed animals were transported in their home cage with food, water and bedding to a 4°C cold room for 6 h per day for 14 consecutive days. Control animals remained undisturbed in their home cage for the same period of time.

2.3. Experiment 1- Effect of CIC stress on LPS responses

One day after the completion of CIC stress, animals were injected with either vehicle (sterile saline, 0.5 ml/kg, intraperitoneally, IP) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 0.2 mg/kg, IP) from Escherichia coli O111:B4 (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO). After the injection, animals were returned to their home cage for either 2 or 5 h before sacrifice by rapid decapitation.

2.4. Experiment 2 - Effect of CIC on footshock responses

One day after the last cold stress or equivalent control period, rats were transported to an adjacent room and either left undisturbed until time of sacrifice (No FS controls), or subjected to a massed series of footshocks delivered in 3 rounds, spaced 15 min apart in a footshock chamber (Habitest Model H10-24, Coulbourn). Each round consisted of 3 × 5 sec scrambled footshocks (1.5 mA) with 5 sec between shocks, followed by 150 sec with no shock, repeated 5 times in 15 min. After the last 15 min round of intermittent shock, the rats remained in the chamber with no further shock for an additional 15 min. Thus, each rat received a total of 45 shocks over a period of 90 min. Following this procedure, rats in all groups were either decapitated immediately (i.e., with no home cage recovery time), or placed back in their home cage for an additional 0.5h, 3.5h or 24h of recovery before sacrifice.

2.5. Tissue and Plasma Collection

The brain was rapidly removed and dissected on ice with the aid of a brain matrix. For the hypothalamus, a 5 mm coronal slab was first cut, approximately between bregma −0.3 mm and −5.3 mm. The hypothalamus was dissected from this slab, by cutting 3 mm laterally from the midline at each side and 3 mm dorsally from the base of the brain (just below the thalamus). The hypothalamus was then dissected into two halves along the midline; one side was used for mRNA extraction and the other for IL1β protein determination. For the mPFC dissection, a 2 mm coronal slab was cut between 2–4 mm caudal to the frontal apex. The area of cortex medial to the internal capsule was then dissected. The brain dissections were immediately frozen in a bath of 2-methylbutane on dry-ice, then stored at −80°C. Trunk blood was collected into a tube containing 100 µl 0.5M EDTA on ice. Plasma was separated by centrifugation (4000 × g, 15 min, 4°C), and stored in aliquots at −80°C.

2.6. RNA Isolation and cDNA synthesis

RNA was isolated using the phenol-chloroform extraction method. Briefly, tissue was homogenized in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using a polytron tissue homogenizer. After a brief incubation, homogenates were centrifuged at 11,900 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and placed in a fresh tube. Chloroform was added and samples were centrifuged at 11,900 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was placed in a new tube and isopropyl alcohol was added. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, then centrifuged at 11,900 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and nucleic acid was washed in 75% ethanol and centrifuged again at 7,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The RNA pellet was re-suspended in RNase-free water then DNase-treated (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was further purified using the Invitrogen PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentration was determined using a Nanodrop 2000 instrument (Thermo Scientific) and all samples were diluted to the same concentration. The 260:280 and 260:230 absorbance ratios were used to determine RNA purity and samples were run on a 1% agarose gel to ensure that degradation or DNA contamination had not occurred. Total RNA (1.5–2.5 µg) was converted to cDNA using the Applied Biosystems High Capacity cDNA RT Kit (Foster City, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. “No Reverse Transcriptase” (No RT) negative controls were used in q-PCR to confirm effective removal of genomic DNA from RNA samples.

2.7. Quantitative RT-PCR

Primer sets were designed using the Integrated DNA Technology PrimerQuest freeware and they were either obtained from IDT or synthesized in the UTHSCSA Nucleic Acids core facility (Table 1). The primer sequences for IL1β and IL6 were from (Frank et al., 2007; Dugan et al., 2009), respectively. All primers were tested for optimal annealing temperature ranges by gradient PCR, and the absence of non-specific amplification was confirmed by running the melt-curve method at the end of each q-PCR reaction. Real-time quantification of diluted cDNA and NoRT controls was performed in triplicate reactions containing sample, SYBR green fluorescence (SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix, BioRad) and 400nM each forward and reverse primers (see Table 1) on a BioRad CFX384 Real Time System. IL-6 and GAPDH cycling conditions consisted of one cycle at 95°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 5 sec), annealing and elongation (60°C, 10 sec).

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for quantitative RT-PCR.

| Gene | Genebank acc.# | Forward primer (5’->3’) | Reverse primer (5’->3’) | Amplicon length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | M98820 | GAAGTCAAGACCAAAGTGG | TGAAGTCAACTATGTCCCG | 124 |

| IL6 | NM_012589 | ATGGATGCTTCCAAACTGGAT | TGAATGACTCTGGCTTTGTCT | 138 |

| COX2 | NM_017232.3 | TGGGTGTGAAAGGAAATAAGGA | GAAGTGCTGGGCAAAGAATG | 128 |

| CxCl1 | NM_030845 | GAGAACCATTAGGTGTCAACCACTGT | ACACGATCCCAGACTCTCATCTCT | 76 |

| MCP1 | NM_031530 | CTGTCTCAGCCAGATGCAGTT AA | TGGGATCATCTTGCCAGT GA | 68 |

| GAPDH | X02231 | AATGCATCCTGCACCACCAAC | TGATGGCATGGACTGTGGTCAT | 100 |

IL-1β and COX2 gene expression and relative GAPDH controls were determined using the Applied Biosystem SYBR green with ROX reaction mix and 400nM each primer on an ABI 7500HT detection system. IL-1β cycling conditions consisted of one cycle at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 15 sec), annealing (55°C, 30 sec), and elongation (72°C, 30 sec). COX2 and GAPDH conditions consisted of one cycle at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 15 sec), annealing and elongation (60°C, 45 sec). In all cases, the relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, after having verified that amplification efficiencies of the primer sets for GAPDH and the gene of interest were comparable. The efficiencies were determined from the slope of a standard curve that included all experimental target CTs within its limits.

In addition, pathway-specific q-PCR arrays (RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays, SA Biosciences, Frederick, MD) were used to identify other classes of genes potentially responsive to CIC stress and LPS. Mini-arrays of oligonucleotides representing genes belonging to several signaling pathways (MAPK, Jak/STAT, NFκB, Wnt, CREB) were screened with 6 separate cDNA mixes obtained from No Stress/Vehicle, No Stress/2h LPS, No Stress/5h LPS, CIC/Vehicle, CIC/2h LPS, CIC/5h LPS hypothalamic samples, following directions for cDNA synthesis and q-PCR assays recommended by the manufacturer. These arrays were run on an ABI 7500HT system. We followed up on genes of interest (CXCL1 and MCP-1) by synthesizing oligonucleotides (see table 1) and confirming the effects in independent q-PCRs using a BioRad CFX384 instrument. The cycling conditions for both of these genes were identical to the ones for IL6 and GAPDH (see above).

2.8. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

IL6 and IL1β protein levels were determined using a commercially available ELISA kit (Quantikine, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to manufacturer's instructions. The intra-assay and inter-assay variability were 6% and 10% respectively. Absorbance at 450 nm (with correction at 570 nm) was measured on an ELx808 instrument (Biotek Instruments). The limit of detectability was 20 pg/ml for IL6 and 5 pg/ml for IL1β. Hypothalamic IL1β was expressed as a function of total protein, as determined by the Bradford Assay (Sigma).

2.9. Radioimmunoassay

Plasma corticosterone and ACTH levels were determined using the ImmuChem Double Antibody 125I RIA Kit (MP Biomedicals, Orangeburg, NY) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The inter-assay coefficient of variation was 10% for Corticosterone and 6% for ACTH.

2.10. Data Analysis

All data were analyzed by one- or two-way ANOVA. Where significant main effects or interactions were detected, the Newman–Keuls test was used for post hoc comparisons. Significance in all analyses was determined at p < 0.05.

Results

3.1. Experiment 1- Effect of CIC stress on LPS-induced responses

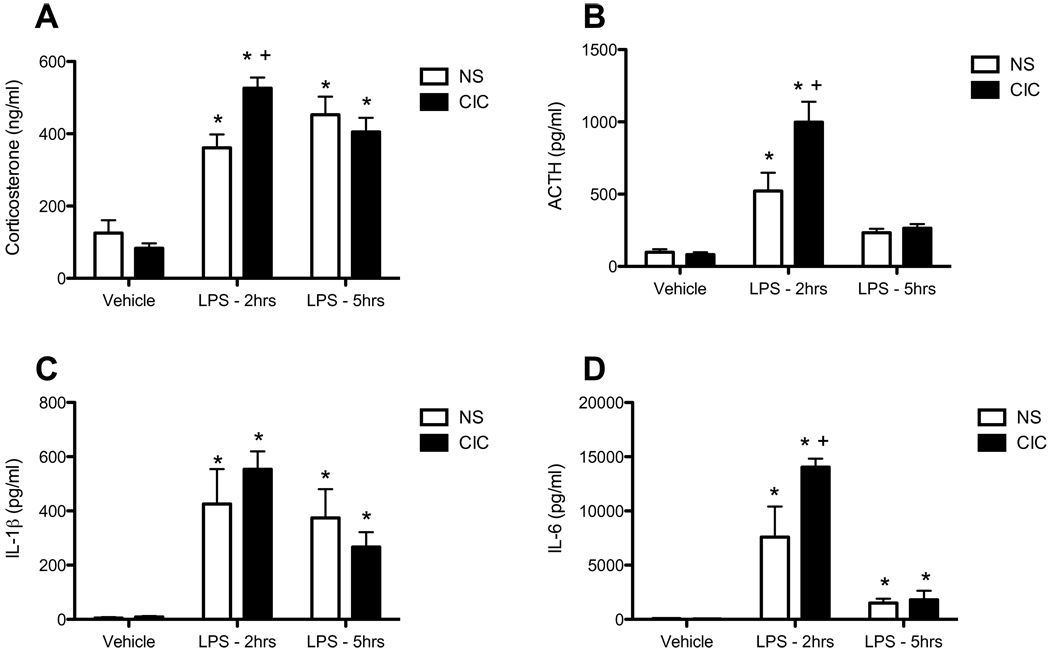

In the first experiment we investigated the effect of CIC stress on peripheral and central immune reactivity to an acute immune challenge, and concomitant HPA axis responses. Intraperitoneal injection of a sub-septic dose of LPS (0.2 mg/kg) increased corticosterone (CORT; F2,68 = 64.3, p<0.0001) and ACTH levels (F2,67 = 43.6, p<0.0001), 2h post-injection (Figures 1A and 1B) and increased both IL1β (F2,68 = 23.3, p<0.0001) and IL6 levels (F2,41 = 42.9, p<0.0001) in plasma (Figure 1C and 1D). CIC stress did not alter basal levels of stress hormones or expression of pro-inflammatory molecules measured 24h after the last cold exposure. However, CIC stress sensitized acute HPA axis reactivity to LPS (for CORT: CIC stress × LPS interaction, F2,68 = 5.84, p< 0.01; for ACTH: Main effect of CIC stress, F1,67 = 7.07, p< 0.01; CIC stress × LPS interaction, F2,67 = 6.46, p< 0.01), evident at 2h post-injection but not at 5h post-injection. CIC stress also augmented LPS-induced plasma IL6 levels (Main effect of CIC stress, F1,41 = 4.71, p< 0.01; CIC stress × LPS interaction, F2,41 = 4.11, p< 0.01). Thus, CIC stress sensitized HPA axis reactivity and at least one peripheral measure of immune activation.

Figure 1. Effects of CIC stress on LPS-induced activation of the HPA axis and levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in plasma.

Rats were sacrificed 2h or 5h after injection of LPS (0.2mg/kg, IP) or an equal volume of saline vehicle. Data from both time points in the vehicle-injected animals were pooled. Measures of corticosterone (panel A, n = 11–14), ACTH (panel B, n = 12–15), IL1β (panel C, n = 11–15) and IL6 (panel D, n = 5–10) were performed on plasma samples derived from trunk blood. * significantly different from Vehicle control in the same treatment group; + significantly different comparing NS and CIC (Chronic Intermittent Cold) at the same time point; all comparisons by Newman-Keuls post-test at p<0.05.

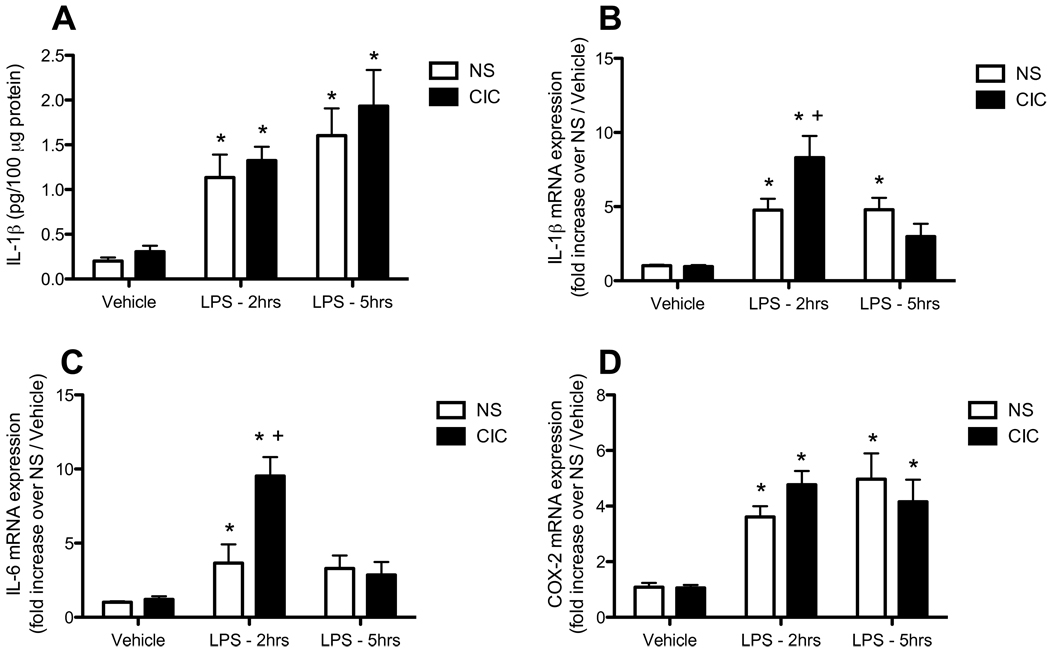

In parallel to effects in the periphery, we also observed sensitized immune reactivity in the brain. In the hypothalamus, LPS induced significant increases in all measures taken, including IL6, COX2 and IL1β mRNA, as well as IL1β protein (all LPS main effects p<0.0001, Figure 2). Further, CIC stress specifically sensitized the LPS-induced increases in the expression of both IL1β and IL6 mRNA (CIC × LPS interaction, F2,44 = 7.37, p< 0.01 and F2,48 = 5.42, p< 0.01, respectively; Figures 2B and 2C). This effect was evident specifically at 2h post injection (post hoc comparisons p<0.05). There was no CIC stress-induced sensitization of the acute LPS response of either COX2 mRNA (Figure 2D) or IL1β protein (Figure 2A) in the hypothalamus.

Figure 2. Effects of CIC stress on LPS-induced changes in pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in hypothalamus.

Rats were sacrificed 2h or 5h after LPS (0.2mg/kg, IP), or an equal volume of saline vehicle. Data from both time points in the vehicle-injected animals were pooled. Levels of IL1β protein (panel A, n= 11–15), IL1β mRNA (panel B, n= 8–10), IL6 mRNA (panel C, n= 7–10) and COX2 mRNA (panel D, 8–10) were measured in the hypothalamus. * significantly different from Vehicle control in the same treatment group; + significantly different comparing NS and CIC (Chronic Intermittent Cold) at the same time point; all comparisons by Newman-Keuls post-test at p<0.05.

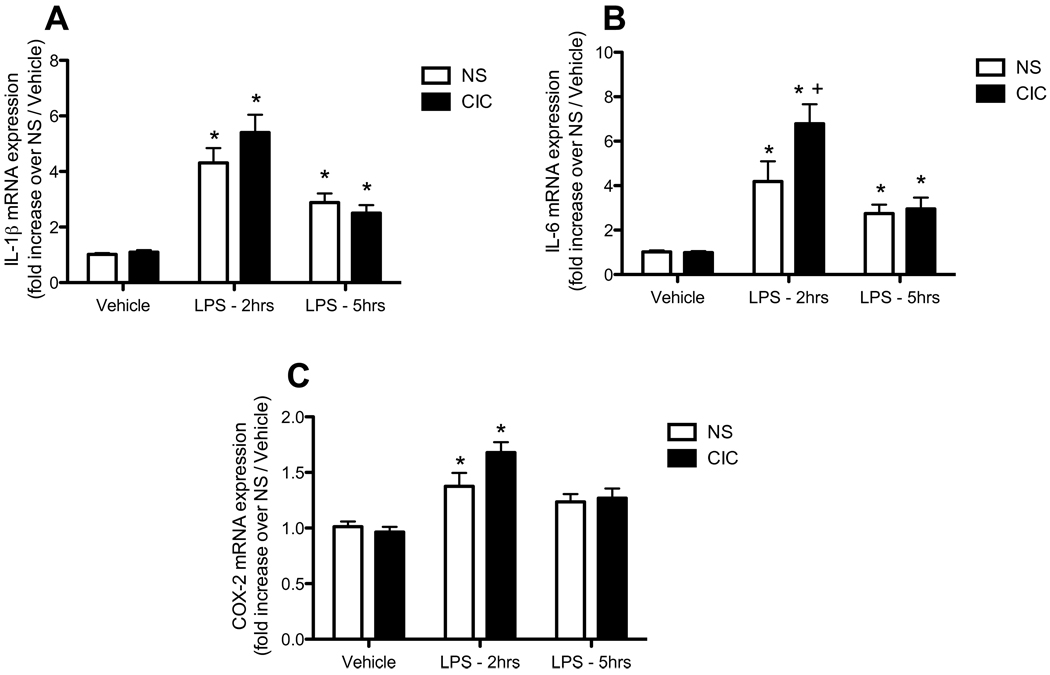

As in the hypothalamus, LPS induced the expression of IL1β IL6 and COX2 mRNA in the mPFC (LPS main effects, all p<0.0001; Figure 3). CIC stress significantly sensitized only the IL6 mRNA response to LPS at 2h, but not 5h, after injection (main effect of CIC stress, F1,68 = 4.34, p< 0.05; CIC stress × LPS interaction, F2,68 = 3.54, p< 0.05; Figure 3B); LPS-induced COX2 expression was up-regulated by CIC stress to an extent that approached significance (CIC stress × LPS interaction, F2,68 = 2.77, p= 0.07; Figure 3C). Thus, CIC stress sensitized immune reactivity to LPS in the periphery and also in both the hypothalamus and the mPFC, and did so most robustly and consistently for IL6.

Figure 3. Effects of CIC stress on LPS-induced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in mPFC.

Rats were sacrificed 2h or 5h after injection of LPS (0.2mg/kg, IP), or an equal volume of saline vehicle. Data from both time points in the vehicle-injected animals were pooled. Levels of IL1β mRNA (panel A, n= 11–15), IL6 mRNA (panel B, n=11–15), and COX2 mRNA (panel C, n=11–15) were measured in the hypothalamus. * significantly different from Vehicle control in the same treatment group; + significantly different comparing NS and CIC (Chronic Intermittent Cold) at the same time point; all comparisons by Newman-Keuls post-test at p<0.05.

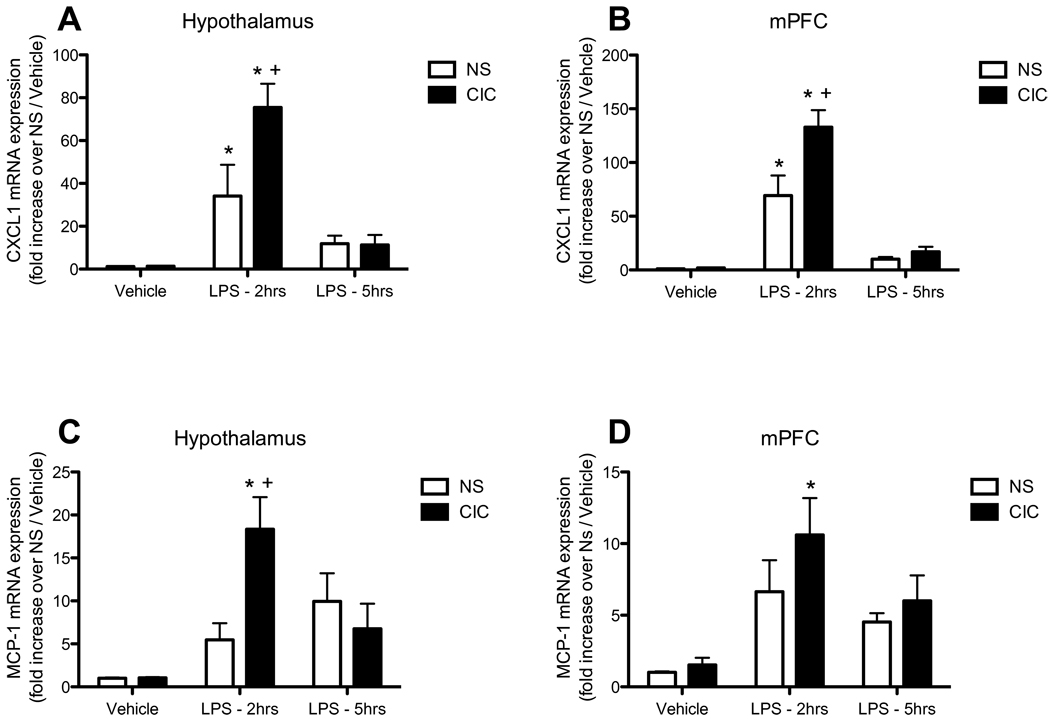

In an effort to identify whether CIC stress sensitized the acute effects of LPS on other classes of inflammatory genes and signaling pathways, we employed a targeted quantitative PCR approach to screen genes belonging to several major signaling pathways (MAPK, Jak/STAT, NFkB, Wnt, CREB). Out of 84 genes screened, 8 showed significant induction with LPS and sensitization of those responses by CIC. Of these, four were chemokines and four were adhesion molecules or matrix metalloproteases (data not shown). We followed up to confirm these results for two of the chemokines, CXCL1/CINC and Ccl2/MCP-1 by independent q-PCR with our own oligonucleotides. As shown in Figure 4, the acute response to LPS of both CXCL1 and MCP-1 was strikingly sensitized in the hypothalamus of CIC-stressed rats (both LPS main effects significant at p<0.0001; both CIC main effects p<0.05; CIC × LPS interactions, F2,44 = 5.00, p<0.01, and F2,44 = 5.42, p< 0.01 for CXCL1 and MCP-1, respectively).

Figure 4. Effects of CIC stress on LPS-induced changes in chemokine expression in hypothalamus and mPFC.

Rats were sacrificed 2h or 5h after injection of LPS (0.2mg/kg, IP), or an equal volume of saline vehicle. Data from both time points in the vehicle-injected animals were pooled. Levels of CXCL1 mRNA (panels A and B, n = 7–10 and 11–15 respectively) and MCP-1 mRNA (panels C and D, n = 7–10 and 11–15, respectively) were measured in the hypothalamus and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). * significantly different from Vehicle control in the same treatment group; + significantly different comparing NS and CIC (Chronic Intermittent Cold) at the same time point; all comparisons by Newman-Keuls post-test at p<0.05.

The LPS-induced increase in expression of CXCL1 in the mPFC was also significantly enhanced by CIC stress (main effect of LPS, F2,68 = 63.2, p<0.0001; main effect of CIC, F1,68 = 9.28, p<0.01; CIC × LPS interaction, F2,68 = 6.41, p< 0.01; Figure 4B), whereas the LPS-induction of MCP-1 mRNA in mPFC (F2,68 = 12.8, p<0.0001) was not significantly increased by CIC stress (Figure 4D). Thus, CIC stress enhanced the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain, and also of specific cytokines involved in cell-cell communication and migration, in response to a novel peripheral immune challenge.

3.2. Experiment 2 - Effect of CIC on Footshock responses

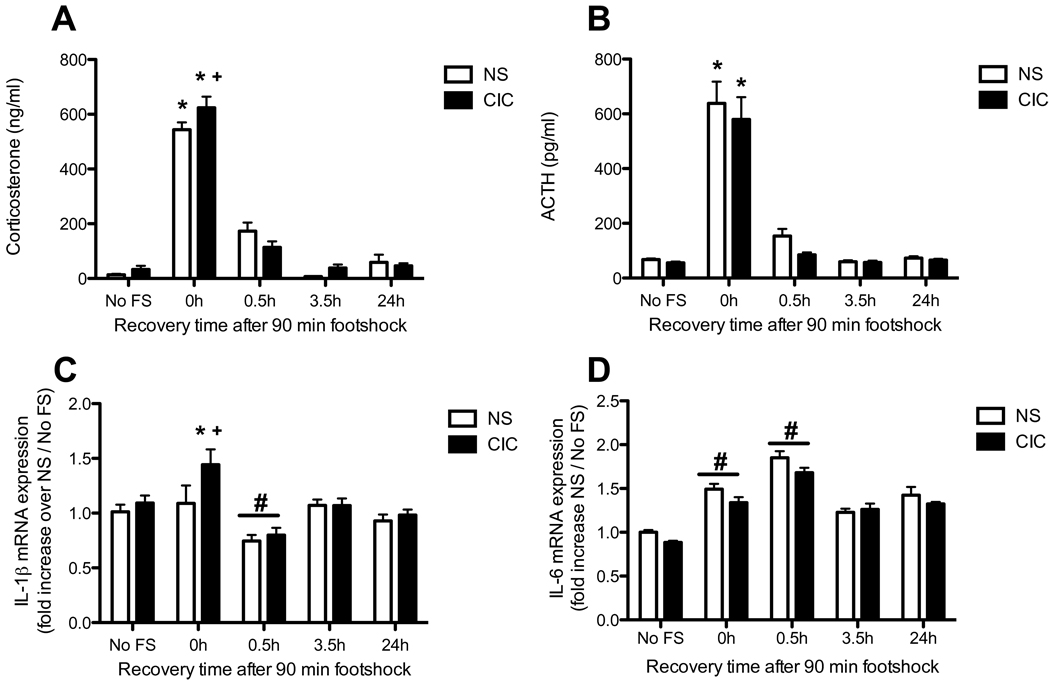

We next examined the effects of previous CIC stress on neuro-immune responses to an acutely stressful non-immune challenge, massed footshock. We observed a significant effect of footshock on both CORT and ACTH (for CORT, F4,121 = 213.9 p<0.0001; for ACTH, F4,130 = 89.3 p<0.0001; Figures 5A and 5B). There was also a significant CIC × footshock interaction for CORT (F4,121 = 2 67, p<0.05). Post hoc analysis showed that CIC stress sensitized the acute CORT response to footshock immediately after the end of the 90 min footshock exposure (i.e., at Time 0 post-shock, see Figure 5A). CIC stress induced a significant increase in IL1β mRNA expression in the hypothalamus (F1,140 = 4.46 p<0.05), also driven primarily by the difference seen immediately after the end of the 90 min footshock exposure (Figure 5C). Footshock had a biphasic effect on IL1β mRNA expression in the hypothalamus (F4,140 = 9.4 p<0.0001), with an increase immediately after the 90 min treatment, followed by a decrease 30 min later. Although there was not a significant interaction, post hoc comparisons revealed a significant difference between CIC and unstressed control rats at the 0h post-shock time point, similar to that observed for CORT. Finally, footshock significantly increased IL6 mRNA expression in the hypothalamus, and the response was similar in control and CIC-stressed animals (F4, 133 = 6.36, p<0.0001; Figure 5D). There were no changes in CXCL1 or MCP-1 mRNA expression in the hypothalamus after footshock (not shown).

Figure 5. Effects of CIC stress on acute footshock-induced activation of the HPA axis hormones and on expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in hypothalamus.

Panel A: Plasma corticosterone levels in Non-Stressed (NS) and CIC-stressed rats, measured immediately after the end of the 90 min footshock session (time point labeled 0h post-shock), or at 0.5h, 3.5h and 24h following the end of the footshock session (n = 12–15). No FS = no footshock. Panel B: Plasma ACTH levels after footshock (n = 11–18). Panel C: Footshock-induced IL1β expression in hypothalamus (n = 12–18). Panel D: Footshock-induced IL6 expression in hypothalamus (n = 11–17). * significantly different from respective No FS control in the same chronic stress treatment group; + significantly different comparing NS and CIC (Chronic Intermittent Cold) at the same time point; # main effect of footshock, significantly different from No FS controls, collapsed across chronic stress treatment (panels C and D only). For clarity, the main effect of footshock is not shown in panels A and B. All comparisons by Newman-Keuls post-test at p<0.05.

4. Discussion

In this study, chronic intermittent cold stress sensitized the acute induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-6, both peripherally and in the hypothalamus and medial prefrontal cortex, in response to a sub-septic dose of LPS, and also sensitized the induction of hypothalamic IL1β in response to acute footshock stress, concomitant with the sensitization of acute HPA stress reactivity shown previously (Pardon et al., 2003; Ma and Morilak, 2005). Sensitization of brain cytokine responses to acute heterotypic challenge supports the hypothesis that enhanced activation of pro-inflammatory neuro-immune signaling could contribute to the dysregulation of neuroendocrine and cognitive processes that are mediated in these brain regions following chronic stress, and that are characteristic of chronic stress-related neuropsychiatric disorders such as major depression (see Ma and Morilak, 2005; Lapiz-Bluhm et al., 2009; Lapiz-Bluhm and Morilak, 2010).

The effects of acute stress on peripheral pro-inflammatory markers, including IL1β, TNFα and IL6, are well documented in rodents, but effects in the brain have been described primarily for IL1β (Shintani et al., 1995; Johnson et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2003; O'Connor et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2004; Deak et al., 2005). Moreover, not all stressors elicit immune responses (Deak et al., 2003; Deak et al., 2005), and the effects of chronic stress have not been well examined. Cold stress, either acute or chronic, has generally been shown to inhibit tonic measures of immune function in the periphery (Bhatnagar et al., 1996; Jiang et al., 2004). In brain, chronic unpredictable stress has been reported to enhance NFκB nuclear translocation and IL1β expression in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of rats injected with LPS either centrally (Espinosa-Oliva et al., 2011) or peripherally (Munhoz et al., 2006). In the latter paper, the authors failed to see increased NFκB activation in the hypothalamus. In the present study, hypothalamic expression of both IL1β and IL6, two genes that are induced by the classical NFκB p65/p50 pathway, was increased following CIC stress. Thus, the profile of inflammatory responses induced in the CNS following chronic stress are both stressor and region specific.

In the present study, the response of IL6 to LPS administration was much more dynamic and plastic than that of IL1β, and the IL6 response was robustly sensitized by prior exposure to CIC stress, in the plasma as well as in the hypothalamus and mPFC. We would note that the sensitization of IL6, but not IL1β response to LPS after chronic cold stress is in general agreement with a similarly selective sensitization of IL6 induction by LPS immediately after acute social stress, reported in a recent paper that went to press as the current paper was being prepared for submission (Gibb et al., 2011). IL6 receptor mRNA is expressed in several stress-responsive brain regions, including the medial preoptic area, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, central amygdala and hippocampus (Vallieres and Rivest, 1997), but few studies have addressed the effects of chronic stress on IL6 expression in the brain. One study reported decreased levels of IL6 in plasma but increased levels in the central nervous system in response to chronic mild stress (Mormede et al., 2002), whereas another revealed no change in brain IL6 levels following chronic social disruption (Bartolomucci et al., 2003). Thus, the present finding that CIC stress exposure robustly sensitized the acute induction of IL6 in the hypothalamus in response to subsequent LPS administration is a novel observation, and supports the hypothesis that altered pro-inflammatory signaling by IL6 in the hypothalamus may contribute to the sensitization of acute HPA stress reactivity seen following CIC stress. Indeed, it has been suggested that IL6 may even be co-released with specific hypothalamic neuropeptides (Ghorbel et al., 2003).

The acute IL6 response to LPS was also sensitized in the mPFC after CIC stress. IL6 expression in the frontal cortex has been linked to ROS production and loss of GABAergic interneurons (Dugan et al., 2009). Evidence in both humans (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2003) and rodents (Dugan et al., 2009) suggests a relationship between elevated IL6 and age-related cognitive decline. Thus, elevated or enhanced IL6 signaling in the prefrontal cortex could potentially contribute to the cognitive impairments we have seen on the attentional set shifting test following CIC stress, which model specific cognitive deficits seen in stress-related psychiatric disorders, such as depression (Lapiz-Bluhm et al., 2009; Lapiz-Bluhm and Morilak, 2010). Importantly, IL6 is also elevated in human plasma and CSF following acute stress, and tonically elevated IL6 levels are associated with treatment-resistant depression (Sluzewska et al., 1997; Lanquillon et al., 2000; Bierhaus et al., 2003).

In addition to the pro-inflammatory cytokines, we also measured the expression of several other factors related to immune function in the brain. Expression of COX2, an inducible enzyme involved in prostaglandin synthesis, was increased by LPS in the hypothalamus and mPFC, and there was a modest trend for CIC stress to increase the acute COX2 response to LPS in both of these brain regions. COX2 expression can be induced in the brain by acute stress (Madrigal et al., 2003), and is associated with increased lipid peroxidation and nitric oxide levels, as well as memory deficits that are attenuated by COX inhibitors (Madrigal et al., 2003; Dhir et al., 2006). Moreover, adjunct treatment of major depression with COX2 inhibitors together with the selective norepinephrine reuptake blocker, reboxetine, has been reported to improve outcome relative to reboxetine alone (Muller et al., 2006). Animals exposed to CIC stress also showed enhanced LPS-induction of the chemokines, MCP-1 and CXCL1, in the hypothalamus and mPFC. MCP-1 activates and attracts monocytic cells and lymphocytes in both the periphery and central nervous system (Deshmane et al., 2009). CXCL1, the rodent homologue of human IL-8, promotes neutrophil migration, and has been shown to be induced by acute stress in the PVN and supraoptic nucleus (Sakamoto et al., 1996; Reyes et al., 2003). In the brain, astrocytes release MCP-1 in response to elevated norepinephrine (NE) transmission, an important component of the stress response (Morilak et al., 2005; Madrigal et al., 2009). Our lab has previously found that noradrenergic receptors in the hypothalamus are also sensitized after CIC stress (Ma and Morilak, 2005), providing a possible mechanism by which the LPS-induced MCP-1 response may have been enhanced. It has been proposed that MCP-1 plays a protective role in the brain by preventing glutamate excitotoxicity (Madrigal et al., 2009). Likewise, CXCL1 is thought to be neurotrophic, and may play a protective role after stress (Semple et al., 2009). Thus, enhanced induction of MCP-1 and CXCL1 after CIC stress may be an adaptive response, serving to protect the brain against cumulative damage caused by repeated or prolonged stress exposure.

Immediately after the end of the 90-min footshock period, there was an increase in IL1β expression in the hypothalamus only in CIC-treated rats (Figure 5C), concomitant with sensitization of the acute HPA response to footshock after CIC stress. The footshock-induced expression of IL1β was relatively small, even in CIC-stressed rats, but IL1β in general is expressed at extremely low levels in the brain in normal conditions, so it is likely that even transient and moderate induction can have powerful signaling consequences, and the fact that this activation was evident only in chronically stressed rats provides further evidence that chronic stress sensitized acute neuroimmune reactivity. Acute footshock has been shown previously to increase IL1β expression in the hypothalamus (Blandino et al., 2006; Blandino et al., 2009). However, in the present study, we did not detect elevated hypothalamic IL1β after footshock in control animals. Procedural differences in footshock delivery and/or shock intensity may have accounted for this discrepancy. Interestingly, 30 min after termination of the footshock, IL1β levels were significantly reduced, which could reflect an inhibitory effect of elevated glucocorticoids, either by directly inhibiting IL1β expression (Zhang et al., 1997), or attenuating transcriptional activity of NFκB (Scheinman et al., 1995; Adcock et al., 1999). Glucocorticoid synthesis inhibitors have been shown to increase the response of IL1β to acute footshock in the hypothalamus (Blandino et al., 2009). Thus, it is possible that the lack of IL1β induction by footshock in control rats was also a result of glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition, perhaps attributable to the relatively high intensity of the acute shock stimulus used in this experiment.

Acute footshock significantly increased IL6 expression in the hypothalamus, evident immediately after termination of the 90-min footshock, and persisting for at least an additional 30 min (Figure 5D), although this response was similar in control and CIC-stressed rats. Acute footshock has been shown previously to induce peripheral IL6 (Zhou et al., 1993), but to our knowledge, this is the first report that footshock can directly elevate brain IL6 levels. This is also consistent with a recent report that acute restraint stress increased IL6 expression in hypothalamic neurons (Jankord et al., 2010).

The present data do not address potential mechanisms by which the acute induction of inflammatory signaling molecules in the CNS may have been enhanced following chronic stress, but the stress responsive brain noradrenergic system and peripheral HPA axis are likely candidates. Acute stress has been shown to alter the response of microglia to LPS ex vivo (Frank et al., 2007), via activation of β-adrenergic receptors (Johnson et al., 2005). Thus, repeated stress, by increasing norepinephrine release in stress-responsive brain regions (see Morilak et al., 2005), may prime microglia to release higher levels of cytokines when subsequently stimulated. Alternatively, and in contrast to the well-known anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids, there is also evidence that glucocorticoids can potentiate inflammatory responses in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Frank et al., 2009; Munhoz et al., 2010). For example, the effects of LPS on hippocampal IL1β and IL6 expression were potentiated by corticosterone administration 24 h prior (Frank et al., 2009). Thus, acute cytokine responses to LPS could have been sensitized by the repeated activation of glucocorticoid release over the course of repeated CIC stress treatment. Further experimentation will be required to address these and other potential mechanisms underlying the sensitization of acute neuroimmune reactivity following chronic stress. Regardless, enhanced immune reactivity in the hypothalamus and mPFC itself represents a potential mechanism by which chronic stress can dysregulate neuroendocrine and cognitive functions mediated in these brain regions, and offers a potentially novel target for treatment of stress-related psychiatric disorders in which these processes are disrupted.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Mr. Ankur Joshi for valuable technical assistance and Dr. Jason O’Connor for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIMH grant MH053851.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adcock IM, Nasuhara Y, Stevens DA, Barnes PJ. Ligand-induced differentiation of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) trans-repression and transactivation: preferential targetting of NF-kappaB and lack of I-kappaB involvement. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:1003–1011. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Anisman H. Cascading effects of stressors and inflammatory immune system activation: implications for major depressive disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009;34:4–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomucci A, Palanza P, Parmigiani S, Pederzani T, Merlot E, Neveu PJ, Dantzer R. Chronic psychosocial stress down-regulates central cytokines mRNA. Brain Res Bull. 2003;62:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F, Lucca A, Brambilla F, Colombo C, Smeraldi E. Interleukine-6 serum levels correlate with response to antidepressant sleep deprivation and sleep phase advance. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:1167–1170. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar S, Shanks N, Meaney MJ. Plaque-forming cell responses and antibody titers following injection of sheep red blood cells in nonstressed, acute, and/or chronically stressed handled and nonhandled animals. Dev Psychobiol. 1996;29:171–181. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199603)29:2<171::AID-DEV6>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierhaus A, Wolf J, Andrassy M, Rohleder N, Humpert PM, Petrov D, Ferstl R, von Eynatten M, Wendt T, Rudofsky G, Joswig M, Morcos M, Schwaninger M, McEwen B, Kirschbaum C, Nawroth PP. A mechanism converting psychosocial stress into mononuclear cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1920–1925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438019100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandino P, Barnum CJ, Deak T. The involvement of norepinephrine and microglia in hypothalamic and splenic IL-1β responses to stress. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;173:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandino P, Barnum CJ, Solomon LG, Larish Y, Lankow BS, Deak T. Gene expression changes in the hypothalamus provide evidence for regionally-selective changes in IL-1 and microglial markers after acute stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:958–968. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LL, Gawuga CE, Tyrka AR, Lee JK, Anderson GM, Price LH. Association between plasma IL-6 response to acute stress and early-life adversity in healthy adults. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2617–2623. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, Capuron L, Irwin MR, Miller AH, Ollat H, Perry VH, Rousey S, Yirmiya R. Identification and treatment of symptoms associated with inflammation in medically ill patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008a;33:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O'Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2008b;9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak T, Bellamy C, D'Agostino LG. Exposure to forced swim stress does not alter central production of IL-1. Brain Res. 2003;972:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak T, Bordner KA, McElderry NK, Barnum CJ, Blandino P, Deak MM, Tammariello SP. Stress-induced increases in hypothalamic IL-1: A systematic analysis of multiple stressor paradigms. Brain Res Bull. 2005;64:541–556. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): An overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:313–326. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir A, Padi SS, Naidu PS, Kulkarni SK. Protective effect of naproxen (non-selective COX-inhibitor) or rofecoxib (selective COX-2 inhibitor) on immobilization stress-induced behavioral and biochemical alterations in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;535:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donegan JJ, Girotti M, Morilak DA. Chronic metabolic stress sensitizes the immune response to LPS in the rat prefrontal cortex. Soc Neurosci. 2010 Abstr 36, Online Program no., 647.7. [Google Scholar]

- Dugan LL, Ali SS, Shekhtman G, Roberts AJ, Lucero J, Quick KL, Behrens MM. IL-6 mediated degeneration of forebrain GABAergic interneurons and cognitive impairment in aged mice through activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase. PLoS One 4. 2009:e5518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Oliva AM, de Pablos RM, Villarán RF, Argüelles S, Venero JL, Machado A, Cano J. Stress is critical for LPS-induced activation of microglia and damage in the rat hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:85–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Baratta MV, Sprunger DB, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Microglia serve as a neuroimmune substrate for stress-induced potentiation of CNS pro-inflammatory cytokine responses. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Miguel ZD, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Prior exposure to glucocorticoids sensitizes the neuroinflammatory and peripheral inflammatory responses to E. coli lipopolysaccharide. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;24:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbel MT, Sharman G, Leroux M, Barrett T, Donovan DM, Becker KG, Murphy D. Microarray analysis reveals interleukin-6 as a novel secretory product of the hypothalamo-neurohypophyseal system. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19280–19285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb J, Hayley S, Poulter MO, Anisman H. Effects of stressors and immune activating agents on peripheral and central cytokines in mouse strains that differ in stressor responsivity. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:468–482. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girotti M, Donegan JJ, Joshi A, Morilak DA. Chronic intermittent cold stress alters the profile of inflammatory signals following acute immune and non-immune challenges in the rat hypothalamus. Soc Neurosci. 2010 Abstr 36, Online Program no., 796.10. [Google Scholar]

- Goujon E, Parnet P, Laye S, Combe C, Kelley KW, Dantzer R. Stress downregulates lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the spleen, pituitary, and brain of mice. Brain Behav Immun. 1995;9:292–303. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1995.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez H, O'Keeffe GW, Gavaldà N, Gallagher D, Davies AM. Nuclear factor κB signaling either stimulates or inhibits neurite growth depending on the phosphorylation status of p65/RelA. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8246–8256. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1941-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankord R, Zhang R, Flak JN, Solomon MB, Albertz J, Herman JP. Stress activation of IL-6 neurons in the hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R343–R351. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00131.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X-H, Guo S-Y, Xu S, Yin Q-Z, Ohshita Y, Naitoh M, Horibe Y, Hisamitsu T. Sympathetic nervous system mediates cold stress-induced suppression of natural killer cytotoxicity in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2004;357:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, Campisi J, Sharkey CM, Kennedy SL, Nickerson M, Greenwood BN, Fleshner M. Catecholamines mediate stress-induced increases in peripheral and central inflammatory cytokines. Neuroscience. 2005;135:1295–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, O'Connor KA, Deak T, Stark M, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Prior stressor exposure sensitizes LPS-induced cytokine production. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:461–476. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, O'Connor KA, Hansen MK, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Effects of prior stress on LPS-induced cytokine and sickness responses. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R422–R432. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00230.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, O'Connor KA, Watkins LR, Maier SF. The role of IL-1β in stress-induced sensitization of proinflammatory cytokine and corticosterone responses. Neuroscience. 2004;127:569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y, Zhang L, Cheng JK, Ji RR. Cytokine mechanisms of central sensitization: distinct and overlapping role of interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α in regulating synaptic and neuronal activity in the superficial spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5189–5194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3338-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, Atkinson C, Malarkey WB, Glaser R. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquillon S, Krieg JC, Bening-Abu-Shach U, Vedder H. Cytokine production and treatment response in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:370–379. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapiz-Bluhm MDS, Morilak DA. A cognitive deficit induced in rats by chronic intermittent cold stress is reversed by chronic antidepressant treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:997–1009. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapiz-Bluhm MDS, Soto-Piña AE, Hensler JG, Morilak DA. Chronic intermittent cold stress and serotonin depletion induce deficits of reversal learning in an attentional set-shifting test in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009;202:329–341. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1224-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Morilak DA. Chronic intermittent cold stress sensitizes the HPA response to a novel acute stress by enhancing noradrenergic influence in the rat paraventricular nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:761–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal JL, Leza JC, Polak P, Kalinin S, Feinstein DL. Astrocyte-derived MCP-1 mediates neuroprotective effects of noradrenaline. J Neurosci. 2009;29:263–267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4926-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal JL, Moro MA, Lizasoain I, Lorenzo P, Fernandez AP, Rodrigo J, Bosca L, Leza JC. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 accounts for restraint stress-induced oxidative status in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1579–1588. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Song C, Lin A, De Jongh R, Van Gastel A, Kenis G, Bosmans E, De Meester I, Benoy I, Neels H, Demedts P, Janca A, Scharpe S, Smith RS. The effects of psychological stress on humans: increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and a Th1-like response in stress-induced anxiety. Cytokine. 1998;10:313–318. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer JC, MacNeil BJ, Sanders V, Pylypas S, Jansen AH, Greenberg AH, Nance DM. Stress-induced suppression of in vivo splenic cytokine production in the rat by neural and hormonal mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18:262–273. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:732–741. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Sze J, Marin T, Arevalo JM, Doll R, Ma R, Cole SW. A functional genomic fingerprint of chronic stress in humans: blunted glucocorticoid and increased NF-κB signaling. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morilak DA, Barrera G, Echevarria DJ, Garcia AS, Hernandez A, Ma S, Petre CO. Role of brain norepinephrine in the behavioral response to stress. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatr. 2005;29:1214–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormede C, Castanon N, Medina C, Moze E, Lestage J, Neveu PJ, Dantzer R. Chronic mild stress in mice decreases peripheral cytokine and increases central cytokine expression independently of IL-10 regulation of the cytokine network. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2002;10:359–366. doi: 10.1159/000071477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller N, Schwarz MJ, Dehning S, Douhe A, Cerovecki A, Goldstein-Muller B, Spellmann I, Hetzel G, Maino K, Kleindienst N, Moller HJ, Arolt V, Riedel M. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib has therapeutic effects in major depression: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled, addon pilot study to reboxetine. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:680–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munhoz CD, Lepsch LB, Kawamoto EM, Malta MB, L. dSL, Avellar MCW, Sapolsky RM, Scavone C. Chronic unpredictable stress exacerbates lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of nuclear factor-κB in the frontal cortex and hippocampus via glucocorticoid secretion. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3813–3820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4398-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munhoz CD, Sorrells SF, Caso JR, Scavone C, Sapolsky RM. Glucocorticoids exacerbate lipopolysaccharide-induced signaling in the frontal cortex and hippocampus in a dose-dependent manner. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13690–13698. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0303-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor KA, Johnson JD, Hansen MK, Wieseler Frank JL, Maksimova E, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Peripheral and central proinflammatory cytokine response to a severe acute stressor. Brain Res. 2003;991:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace TW, Mletzko TC, Alagbe O, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB, Miller AH, Heim CM. Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1630–1633. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardon M-C, Ma S, Morilak DA. Chronic cold stress sensitizes brain noradrenergic reactivity and noradrenergic facilitation of the HPA stress response in Wistar Kyoto rats. Brain Res. 2003;971:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes TM, Walker JR, DeCino C, Hogenesch JB, Sawchenko PE. Categorically distinct acute stressors elicit dissimilar transcriptional profiles in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5607–5616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05607.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto Y, Koike K, Kiyama H, Konishi K, Watanabe K, Tsurufuji S, Bicknell RJ, Hirota K, Miyake A. A stress-sensitive chemokinergic neuronal pathway in the hypothalamo-pituitary system. Neuroscience. 1996;75:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinman RI, Cogswell PC, Lofquist AK, Baldwin AS. Role of transcriptional activation of I kappa B alpha in mediation of immunosuppression by glucocorticoids. Science. 1995;270:283–286. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple BD, Kossmann T, Morganti-Kossmann MC. Role of chemokines in CNS health and pathology: a focus on the CCL2/CCR2 and CXCL8/CXCR2 networks. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;30:459–473. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani F, Nakaki T, Kanba S, Sato K, Yagi G, Shiozawa M, Aiso S, Kato R, Asai M. Involvement of interleukin-1 in immobilization stress-induced increase in plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone and in release of hypothalamic monoamines in the rat. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1961–1970. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01961.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluzewska A, Sobieska M, Rybakowski JK. Changes in acute-phase proteins during lithium potentiation of antidepressants in refractory depression. Neuropsychobiology. 1997;35:123–127. doi: 10.1159/000119332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallieres L, Rivest S. Regulation of the genes encoding interleukin-6, its receptor, and gp130 in the rat brain in response to the immune activator lipopolysaccharide and the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1668–1683. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Zhang L, Duff GW. A negative regulatory region containing a glucocorticosteroid response element (nGRE) in the human interleukin-1beta gene. DNA Cell Biol. 1997;16:145–152. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Kusnecov AW, Shurin MR, DePaoli M, Rabin BS. Exposure to physical and psychological stressors elevates plasma interleukin 6: Relationship to the activation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2523–2530. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.8243274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorrilla EP, Luborsky L, McKay JR, Rosenthal R, Houldin A, Tax A, McCorkle R, Seligman DA, Schmidt K. The relationship of depression and stressors to immunological assays: a meta-analytic review. Brain Behav Immun. 2001;15:199–226. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2000.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]