Abstract

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is a pain mediator, elevated in skin after injury, which potentiates noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli (hyperalgesia) through the activation of ETA (and, perhaps, ETB) receptors on pain fibers. Part of the mechanism underlying this effect has recently been shown to involve potentiation of neuronal TRPV1 by PKCε. However, the early steps of this pathway, which is recapitulated in HEK 293 cells co-expressing TRPV1 and ETA receptors, remain unexplored. To clarify these steps we investigated the pharmacological profile and signaling properties of native endothelin receptors in immortalized cell lines including HEK 293 and ND-7 model sensory neurons. Previously we showed that in ND7/104, a dorsal root ganglia-derived cell line, ET-1 elicits a rise in intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]in) which is blocked by BQ-123, an ETA receptor antagonist, but not by BQ-788, an ETB receptor antagonist, suggesting that ETA receptors mediate this effect. Here we extend these findings to HEK 293T cells. Examination of the expression of ETA and ETB receptors by RT-PCR and [125I]-ET-1 binding experiments confirms the slight predominance of ETA receptor binding sites and messenger RNA in both ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells. In addition, selective agonists of the ETB receptor (sarafotoxin 6c, BQ-3020 or IRL-1620) do not induce a transient increase in [Ca2+]in. Furthermore, reduction of ETB mRNA levels by siRNA do not abrogate calcium mobilization by ET-1 in HEK 293T cells, corroborating the lack of an ETB receptor role in this response. However, in cells with low endogenous ETA mRNA levels, ET-1 does not induce a transient increase in [Ca2+]in. Observation of the [Ca2+]in elevation in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells in the absence of extracellular calcium suggests that ET-1 elicits a release of calcium from intracellular stores, and pretreatment of the cells with pertussis toxin or a selective inhibitor of phospholipase C (PLC) point to a mechanism involving Gαq/11 coupling.

These results are consistent with the hypothesis that a certain threshold of ETA receptor expression is necessary to drive a transient [Ca2+]in increase in these cells and that this process involves release of calcium from intracellular stores following Gαq/11 activation.

Keywords: Endothelin-1, ETA receptor, ETB receptor, HEK 293T, ND7/104, calcium, Gαq/11

1. Introduction

Endothelin-1 (ET-1), a 21 amino acid peptide [1], is produced by a wide range of cell types where it mediates myriad cellular effects [2]. Hence, ET-1 has been linked to many physiological processes with identified roles in health and disease [3,4]. ET-1 binds, with sub-nanomolar affinities, to two class A type G protein-coupled receptors known as ETA and ETB [5,6]. In humans these receptors share ~51% amino acid sequence identity and are encoded by two distinct genes (EDNRA and EDNRB) located on chromosome 4 (4q31.22) and 13 (13q22), respectively. ETA and ETB receptors display different selectivity for endothelins [7] as well as for many competitive peptide or non-peptide antagonists which are important tools to study the function of each receptor type [8].

Over the years the relevance of endogenous ET-1 in pain processing has become apparent, including its role in inflammatory, cancer and neuropathic pain (see [9] for a recent review). In the skin, where ET-1 initiates local nociception following injury [10] and modulates the duration of inflammatory pain [11], two different mechanisms appear to be at play. Subcutaneous injection of high doses of ET-1 (100 to 500 µM) into the rat’s plantar region elicits pain-like flinching behavior and induces selective firing of nociceptive fibers (C- and A delta-) but not of the non-nociceptive A beta-fibers [12]. This effect, which is blocked by BQ-123, a selective ETA receptor antagonist, is likely directly mediated by the activation of ETA receptors present in a subset of small peptidergic (CGRP+) and non-peptidergic neurons [13–15]. Activation of ETA leads to increased neuronal excitability by lowering the threshold of activation of tetrodotoxin-insensitive sodium channels [16] and by reducing the current from delayed rectifier potassium channels [17]. In addition, a mechanism involving TRPV1, a non-specific cation channel activated by a variety of noxious stimuli and predominantly found on unmyelinated C-nociceptors [18], has been demonstrated. TRPV1-deficient mice show attenuated ET-1-induced nocifensive behaviors such as licking, flinching and biting [19].

Subcutaneous injection of relatively low concentrations (2–10 µM) of ET-1 induces thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia. These elevated responses to applied stimuli occur with little of the overt flinching or licking seen with higher concentrations [20–23]. Tissue specific ablation of ETA receptors in Nav1.8-expressing nociceptors completely suppresses tactile allodynia as well as late phase thermal hyperalgesia caused by ET-l’s local injection [11]. Acute thermal hyperalgesia, which is likely mediated by TRPV1 receptors, since it is capsazepine-sensitive, is attenuated by antagonists of both ETA and ETB receptors [23]. About half of the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) sensory neuron population expressing TRPV1 is immuno-positive for ETA receptors, and activation of ETA receptors with 10 nM ET-1 enhances a capsaicin-induced increase in intracellular calcium in dissociated mouse DRG neurons [24]. This effect is mediated by ETA receptor activating PKCε, which in turn phosphorylates TRPV1 at residue S800, thus potentiating TRPV1 activity [24,25]. This mechanism was initially recognized in HEK 293 cells which, like DRG neurons, express the diacylglycerol (DAG)-activated PKCε [26]. Interestingly, heterologous co-expression of ETB receptors and TRPV1 in HEK293 cells demonstrates that ETB can also sensitize TRPV1 through this pathway, although to a lesser extent than ETA receptors [25].

Despite these significant breakthroughs, the cascade of events leading to the production of DAG and subsequent translocation of PKCε from the cytosol to the cell membrane following ET-1 application remains relatively unexplored. Our laboratory reported previously that in the DRG-derived cell line ND7/104, ET-1 induces a transient rise of intracellular calcium, [Ca+2]in, emanating from intracellular stores, which is blocked by BQ-123 but not by the ETB selective antagonist BQ-788 [27]. More recent work has demonstrated that in freshly dissociated mouse DRG neurons 10 nM ET-1 also induces a very small intracellular calcium increase from intracellular stores which is exclusively dependent on ETA receptors. Conversely, satellite cells, which are thought to express exclusively ETB receptors [13–15], show a large intracellular calcium increase stimulated by 10 nM ET-1 that is ETB receptor-dependent [24]. Taken together, these data emphasize the importance of intracellular calcium modulation in ET receptor-mediated pain signaling (see [28] for a recent review).

In the present paper we use quantitative PCR (qPCR) and radio-ligand binding to show that both ETA and ETB receptors are expressed by ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells. In both cell types, however, ET-1-induced calcium responses are only mediated by ETA receptors, possibly due to sub-threshold ETB receptor expression. We also show that this ET-1-stimulated calcium response depends on PLC and is likely mediated through the Gαq/11 signaling pathway.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Pharmacological reagents

Endothelin-1 was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (Lausen, Switzerland). BQ-123, BQ-788, IRL-1620 and BQ-3020 were from American Peptide Co. (Sunnyvale, CA). IRL-2500 was from Tocris (Ellsville, MO). Sarafotoxin 6c was from RBI (Natick, MA). Forskolin was from MP Biomedicals (Santa Ana, CA). ATP, Bradykinin, Ionomycin, Cholera toxin, Pertussis toxin, MDL-12,330A and U73122 were from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Cell cultures

ND7/104 (a hybrid cell line derived from rat dorsal root ganglia neurons hybridized with N18TG2 mouse neuroblastoma cells) was a generous gift from Dr. P. Hogan (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). The HEK 293T cell line was generously donated by Dr. Ging-Kuo Wang (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), and the HEK 293 cell line was provided by Dr. K. Sugimoto (Department of Anesthesiology, Nagoya University Hospital, Nagoya, Japan). All cell lines were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), penicillin (100U), and streptomycin (100µg) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), at 37°C in 5% CO2.

2.3. Quantitative RT-PCR

Cells were grown to sub-confluence in 6-well plates before harvest and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality and concentration were determined using a nanodrop and quality assessed by visual inspection after separation on an agarose gel. cDNA synthesis on 500 ng of total RNA was carried out with random hexamers using a First strand cDNA kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed in triplicate on a fraction of the cDNA in a Miniopticon thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using Evagreen™ PCR mix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) under the following conditions: 94 °C for 3 min, 45 cycles (94 °C for 30 sec, 60 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 1 min) followed by a melting curve to verify the specificity of the primers. All the primer pairs employed gave rise to a single peak confirming their specificity (data not shown). All primer pairs were designed to amplify rodent and human templates. The ETA primers used were ETAFRW: 5’-GGCTTCGTCATGGTACCC-3’ and ETAREV2: 5’-CAAAGAGCCACCAGTCCT-3 which amplify a 116 bp DNA fragment (NM_010332; NM_001957). The ETB primers were ETBFRW4: 5’-GACTGGCCATTTGGAGCTG-3’ and ETBREV4: 5’-GGAACCCCAATTCCTTTAATTC-3 which amplify a 145 bp DNA fragment (NM_007904; BC014472). Cyclophilin A primers were QCYCLOAFRW: 5’-ATCTGCACTGCCAAGACTGA-3’ and QCYCLOAREV: 5’-ATGGTGATCTTCTTGCTGGTCT-3’ which amplify a 134 bp DNA fragment (BC137057; BC099478). Internal controls included omitting reverse-transcriptase or templates to check for contamination of the starting material. Efficiency of amplification was determined for each primer pair in triplicate, using 10-fold serial dilution of starting cDNA, using the REST-MCS software [29]. The relative expression of the target gene was calculated based on real-time PCR efficiencies and the threshold value of the unknown sample versus the standard sample [30]. Data are expressed in fold-changes ± SEM corresponding to the ratio between experimental groups or cell lines. Student t-test with unequal variance was used for analyses (Welch t-test, Microsoft Excel).

2.4. Calcium imaging experiments

Twenty four to forty eight hours prior to calcium imaging the cells were seeded at a density of 106 cells/plate onto a Poly-L-Lysine-coated coverslip (VWR, Radnor, PA) and were ~80% confluent at the time of assay. Cells were rinsed twice with Ringer’s solution (NaCl 155 mM, KCl 4.5 mM, CaCl2 2 mM, MgCl2 1 mM, D-glucose 10 mM, Hepes 5 mM) and loaded for 30 min at 37 °C with 4 µM Fura 2-AM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) dissolved in Ringer with 0.025 % (w/v) Pluronic F-127 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Then cells were incubated in the dark at 25 °C for an additional 15 min prior to Ca2+ imaging.

Solutions diluted in normal Ringer or calcium-free Ringer solution (NaCl 155 mM, KCl 4.5 mM, MgCl2 3 mM, D-glucose 10 mM, Hepes 5 mM) were applied using a micropipette to the coverslip fitted in a custom-made recording chamber. The excess solution was aspirated by an attached vacuum line. Cells were monitored on an inverted Diaphot 300 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) equipped with a PTI-IC100 digital camera (PTI, Birmingham, NJ). Acquisition of the fluorescence intensity following 340/380-nm excitation and 535-nm emission wavelengths was recorded using the PTI software for 240 seconds. At the end of the experiment ATP (40 µM) was applied as a control to stimulate endogenous purinergic receptors.

The Ca2+ changes are expressed as the fractional change in fluorescence light intensity over the baseline intensity: ΔF/F=(F-F0)/F0, where F is the fluorescence light intensity at each time point and F0 is the fluorescence intensity averaged over 30 seconds before the stimulus application. The peak intensity following stimulus administration was averaged with the measurements immediately before and after it to correct for intrinsic fluctuations of the florescent signal. The data were normalized to the response elicited by ATP by dividing the peak value (averaged over these 3 data points) of the stimulus response by the peak value of the ATP response for each cell. In cells treated with U73122 the data were normalized to the response elicited by 10 µM ionomycin instead of ATP. Data are presented as the mean maximum normalized fluorescence increase averaged for at least 15 representative cells from 3 independent experiments, unless noted otherwise. The response to ET-1 (30 nM) was from at least 40 cells from 8–9 independent experiments. The ATP response, presumably mediated by endogenous P2X and P2Y receptors, was comparable across cell types. Statistical significance between the control group (typically ET-1 30 nM) and the experimental groups was established following two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests, calculated using Graphpad Prism software (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Responses were highly reproducible, reflecting the low variability observed when using clonal cell lines.

2.5. 125I-ET-1 binding assays

Equilibrium binding studies were conducted on 90 % confluent cells in 12-well plates, 24 h after seeding. All binding studies were performed at 4 °C to prevent receptor internalization. Cells were incubated for 3 h in 1 mL of 0.1 % BSA in culture medium, with concentrations of [125I]-ET-1 (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) ranging from 10 to 600 pM in saturation binding studies or constant at 30 pM in unlabelled ligand competition studies. After incubation, supernatants were pooled from quadruplicates of each condition and measured for radioactivity to determine free [125I]-ET-1. Cells were washed thoroughly two times with 0.1 % BSA in culture medium and solubilized overnight with 0.5 mL 1.0 N NaOH. The culture dishes were scraped the following day to collect all the cellular materials and the collected solution was then neutralized with 0.5 mL 1.0 N HCl. These samples were transferred to 7 mL scintillation vials and mixed thoroughly with Ecolite(+)™ Liquid Scintillation Cocktail (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). Radioactivity was measured for 5 min/sample in a Beckman Model LS8500 (Beckman, Inc; Palo Alto, CA) scintillation counter. Specific binding was defined as the difference between total binding and nonspecific binding, the latter determined by co-incubation with 500 nM unlabelled ET-1. Protein concentration was measured using a BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

Specific binding versus free [125I-ET-1] data were fit by the following logistics equation (Eq.1), analogous to the Hill equation:

| (Eq.1) |

where [*ET-1] is the free 125I-ET-1 concentration in the supernatant, Usat is the amount of 125I-ET-1 bound to receptors, Bmax is the total number of binding sites, nH is an empirical parameter that reflects cooperativity in binding and KD is the equilibrium dissociation constant.

For the competition binding studies, which used increasing concentrations of the ETA-selective antagonist BQ-123 and a nominally constant concentration of 125I-ET-1, data were fit by the following equation:

| (Eq.2) |

Optimal fits of these equations to the experimental data generated by Graphpad Prism (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) provided estimates of KD, Bmax, nH, and KD or Ki from individual experiments. Three such experiments were separately analyzed for the parameter values which were then averaged and reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters for [125I]-ET-1 Binding to Intact Cells (mean ± SEM; n=3)

| Cell Type | ND-7/104 | HEK 293T | HEK 293 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bmax | 38.4 ± 4.1 fmol/mg | 33.7 ± 10.0 fmol/mg | 3.6 ± 0.5 fmol/mg |

| KD (I-ET-1) | 0.07 ± 0.01 nM | 0.17 ± 0.10 nM | 0.06 ± 0.02 nM |

| nH | 1.75 ± 0.39 | 1.24 ± 0.48 | 3.48 ± 3.78 |

| KI (BQ-123) | 0.35 ± 0.05 nM | 0.21 ± 0.01 nM | 0.39 ± 0.14 nM |

| nH | −0.82 ± 0.04 | −0.73 ± 0.22 | −0.56 ± 0.16 |

| High affinity KI BQ-123 | 2.26 ± 0.33 nM | 5.47 ± 1.52 nM | 0.43 ± 0.07 nM |

| Low affinity KI BQ-123 | 1899.00 ± 3812.00 nM | N.D. | 195.10 ± 135.60 nM |

N.D.: not determined

2.6. Intracellular cAMP measurements

Ten thousand cells/well were plated onto 96-well plates 24–36 h prior to experimentation. Activation of the receptors was conducted by adding the appropriate agonist in solution in PBS to the wells and incubating the plate for 10 min at 37 °C. cAMP levels were subsequently measured by using a cAMP enzyme immunoassay (GE healthcare, Rochester, NY) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cAMP production was normalized to the protein concentration in each well, determined using a BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Briefly, 50 µl of protein samples were added to 200 µl of 50:1 Pierce’s reagents A, and B, incubated for half an hour at 37 °C, and protein concentration was determined at 562-nm using a Bio-Rad microplate reader. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis of the data was performed with Graphpad Prism (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

2.7. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfections

HEK 293T cells were reverse transfected at the time that they were seeded onto coverslips prior to imaging. Following the recommendations of the manufacturer ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool ETRB siRNA or ON-TARGETplus siCONTROL non-targeting siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) was first diluted in Opti-MEM I Medium without serum and then combined with diluted RNAiMAX lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. The complex was then diluted in culture media (DMEM +10% FBS without antibiotics) containing suspended cells which were then plated onto poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips. Six hours after plating, the media containing the transfection material was removed and the cells treated as described under 2.3. Calcium imaging experiments were conducted 48 h later as described under 2.4 and the cells collected for qPCR analysis (see procedure under 2.3).

3. Results and Discussion

3. 1. ETA and ETB receptors are expressed at different levels in ND7/104, HEK 293T and HEK 293 cells

To determine the repertoire of ET receptors in ND7/104, HEK 293T and HEK 293 cells we first conducted quantitative RT-PCR on total RNA extracted from these cells. We used primers specific for ETA or ETB receptors as well as for cyclophilin A, a housekeeping gene used for the normalization of the samples. As shown in Figure 1, messenger RNA for the endothelin A and B receptors was detected in all three cell lines. ETA mRNA levels were comparable between ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells (ANOVA, p > 0.05), but HEK 293 cells had significantly less (ANOVA, p < 0.01). In the same manner, ND7/104 and HEK 293T have significantly more ETB mRNA than HEK 293 cells (ANOVA, p < 0.001) while ND7/104 and HEK 293T have comparable ETB mRNA levels (ANOVA, p >0.05). Comparison of ETA and ETB messenger RNA levels within cell lines indicated that levels are comparable in ND7/104 and HEK 293 cells but that ETA is significantly more abundant than ETB in HEK 293T cells (Welsh t-test, p < 0.05).

Figure 1. ETA and ETB transcripts in HEK 293T, HEK 293, and ND7/104 cells.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of ETA and ETB receptors transcript abundance in HEK 293T, ND7-104 and HEK 293 cells using specific primers. Results are normalized to cyclophilin A expression levels and expressed in arbitrary units as the mean ± SEM of 4 independent biological samples. White bars represent the ETA messenger level and black bars are for ETB. ETA and ETB receptor levels were significantly lower in HEK 293 cells compared to HEK 293T and ND7/104 cells. ETB message levels were comparable to that of ETA in ND7/104 cells, but were significantly less than ETA levels in both HEK cell lines. (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; ANOVA)

Unfortunately, we were unable to validate the presence of the receptor proteins in these cells by Western blot analysis due to the lack of specificity of the commercial antibodies we tested. All anti- ETB receptor antibodies tested failed to recognize an HA-tagged ETB receptor protein otherwise detected by the anti-HA antibody (data not shown). This problem corroborates recent concerns about commercial ET receptor antibodies raised by another group using immunoprecipitation to study receptor heterodimerization [31].

Next we sought to determine whether mRNA expression levels are correlated with ET-1 binding sites. To do so, intact ND7/104, HEK 293T and HEK 293 cells were incubated with [125I]-ET-1 for 3 h, at 4 °C to prevent receptor internalization while reaching equilibrium binding. All parameters from the binding experiments are collected in Table 1.

Saturation binding data were analyzed by fits of the logistics equation (Eq 1, see Methods) to determine a binding capacity, Bmax. This measure of total ET receptor number on the plasma membrane equalled 38.4 ± 4.1 fmol/mg (n=3) in ND7/104 cells (Figure 2) and 33.7 ± 10.0 fmol/mg (n=3) in HEK 293T cells (Figure 2), whereas much less (3.6 ± 0.5 fmol/mg; n=3) was detected in HEK 293 cells (Figure 2, Table 1). Equilibrium dissociation constants, KD, were similar for ND7/104 and HEK 293 cells, at 70 ± 10 pM and 58 ± 18 pM, respectively. In HEK 293T cells the affinity was slightly lower, with KD = 170 ± 100 pM (Table 1). Our results are in line with [125I]-ET-1 binding experiments conducted on pituitary tissue sections, reporting a KD of 71 pM and a Bmax of 120 fmol/mg [32]. In contrast, membranes of HEK 293 cells over-expressing cloned tagged-ETA or -ETB receptors displayed much higher Bmax values, as expected, (~ 7 pmol/mg) and slightly lower KDs (~ 30 pM for ETA receptors and ~10 pM for ETB receptors; ref. [33].

Figure 2. Specific binding of [125I]ET-1 in intact ND7/104, HEK 293T, and HEK 293 cells.

Saturation binding of [125I]ET-1 on intact ND7/104, HEK 293T, and HEK 293 cells respectively. Maximal binding capacity is 38.4 ± 4.1 fmol/mg (n=3), 33.7 ± 10.0 fmol/mg (n=3), and 3.6 ± 0.5 fmol/mg (n=3) respectively. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Fits of the binding data showed a Hill coefficient, nH, around 2 (with a large error in this parameter for HEK-293 cells where the binding was very low) (Table 1). It thus appears that there is some positive cooperativity in the binding of [125I]-ET-1 to the receptors in these cells.

Competition studies were subsequently performed using a range of concentrations of BQ-123, an ETA receptor-selective antagonist, and a constant [125I-ET-1]. These experiments determined both the inhibitory equilibrium dissociation constants, Ki, for this antagonist, and the proportions of ETA and ETB receptors in the different cell lines (Figure 3). In ND-7/104 cells, Ki for BQ-123 = 2.26 ± 0.33 nM; in HEK 293T cells, Ki = 5.47 ± 1.52 nM, and in HEK 293 cells, Ki = 0.43 ± 0.07 nM (Table 1). Fitting of the competition binding data by a one-site or a two-site model indicated a better fit for the latter in ND7/104 and HEK 293 cells, where BQ-123 bound to a high (Ki < 10 nM) and a low (Ki > 100 nM) affinity site (Figure 3). The Ki for low affinity binding in HEK 293T cells was too high to allow its estimation (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Competition binding experiments on intact ND7/104, HEK 293T, and HEK 293 cells.

30 pM [125I]ET-1 was used in the presence of increasing concentrations of BQ-123. In ND7/104 and HEK 293 cells BQ-123 appears to bind to a high (Ki < 10 nM) and a low (Ki > 100 nM) affinity site. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

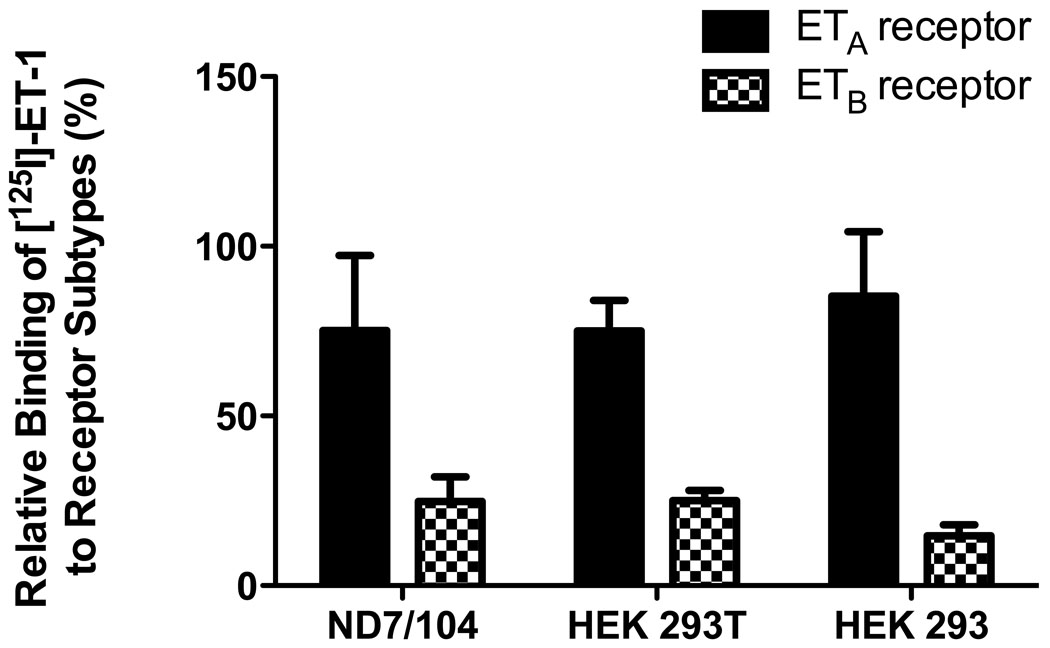

Based on these results, and the assumption that the high-affinity site corresponds to ETA receptors, we used 100 nM BQ-123 in subsequent experiments to determine ETA and ETB receptor densities in these cells (Figure 4). ETB receptor-specific binding was inferred by subtraction of the ETA receptor density from the total. (Competition studies were attempted with BQ-788, the ETB receptor antagonists, and several ETB receptor agonists, but the results were anomalous and will not be described here.) In ND7/104 cells ETA binding accounted for 75.2 ± 22.2 %, with the remainder, 24.8 ± 7.3 %, assigned as ETB. In HEK 293T cells the percentage of ETA receptor sites was of 75 ± 9 % while that of ETB sites was of 25 ± 3 %. In HEK 293 cells ETA and ETB receptor-selective binding accounted for 85.3 ± 19 % and 14.7 ± 3.3 %, respectively (Figure 4). Thus, ETA and ETB receptor binding sites are represented at a proportion close to 3:1 in all three cell lines.

Figure 4. Relative surface expression of endothelin receptor subtypes in ND7/104, HEK 293T, and HEK 293 cells.

100 nM of the selective ETA receptor antagonist BQ-123 was used to define ETA receptor surface expression. Endothelin-A receptors account for 75 ± 22 % binding in ND7/104 cells, 75 ± 9 % binding in HEK 293T cells, and 85 ± 19 % binding in HEK 293 cells. Endothelin-B receptors account for 25 ± 7 % binding in ND7/104 cells, 25 ± 3 % binding in HEK 293T cells, and 15 ± 3 % binding in HEK 293 cells. Values are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

This ratio is in the same direction as the proportions of mRNA obtained by qPCR for the different receptor sub-types where the observed ratio is close to 2:1 in HEK 293T and HEK 293 cells. However, in ND7/104 the ratio of mRNA for the receptor sub-types is closer to 1:1, although with a large error for ETB. To our knowledge this is the first quantitative report of endogenous ET receptor messenger RNA levels and ET-1 binding sites in these cell lines, some of which have been used extensively for ET receptor heterologous expression studies [24,25,33–37]. The presence of both ETA and ETB receptors in ND7/104 cells indicates that this cell line might be more representative of a subset of trigeminal ganglionic neurons which, unlike lumbar non-myelinated primary sensory neurons such as those found in DRG, express both ETA and ETB receptors [38]. Note that high and low affinity sites for BQ-123, as we observe here, have been reported in the past for cells co-expressing both receptor subtypes, such as canine spleen cells [39]. However, in that study the affinity of the weaker binding site was quite low, similar to that obtained from Chinese hamster ovary cells over-expressing the cloned human ETB receptor (Ki ~60 µM) [40]; this is a Ki much higher than what we calculate in ND7/104 and HEK 293 cells (< 2 µM). Further experiments will determine whether this low affinity binding is attributable to ETB or ETA/ETB heteromers.

Published ligand binding studies have reported atypical pharmacological profiles for ET-1 receptors in cells expressing both receptor subtypes [32,41]. Splice variants and heterodimerization of ETA and ETB have been proposed to explain these phenomena [33], but the precise molecular mechanisms underlying these effects remain elusive. ND7/104 and HEK 239T cells endogenously co-express both receptor subtypes and represent a valuable and dependable tool to study at high throughput receptor/ligand interactions and putative cooperativity between the two subtypes.

3.2. ET-1 elicits an ETA mediated rise of intracellular calcium in ND7/104 and HEK 293T, but not in HEK 293 cells

Previous studies using ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells reported that ET-1 evokes an increase in intracellular calcium levels in these cells, which is blocked by BQ-123 in ND7/104 cells [27,42]. Given the different receptor expression levels among the three cell lines used here, we sought to compare their [Ca2+]in mobilization responses to ET-1. Cells were submitted to ratiometric calcium imaging analysis during exposure to 30 or 100 nM ET-1. Note that because ET-1 induces a well-documented, long-lasting down regulation of the endothelin receptors, different coverslips were used for the different concentrations of ligands tested. In addition, to account for potential variability in the loading of the cells which might confound comparison between experiments, individual cellular responses to endothelin receptor agonists or antagonists were normalized to their response to ATP (40 µM). ATP induced a strong and comparable calcium response in all three cell lines through endogenous purinergic receptors [43] and was therefore also used as an indicator of the cell viability.

Endothelin-1 at 30 nM and 100 nM elicited [Ca2+]in mobilization in ~ 35% of both the ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells. The amplitudes of these responses were similar to that elicited by ATP (40 µM; Figures 5, 6A). (Importantly, neither the amplitude or duration of the calcium transient induced by ATP (40 µM) were altered following exposure to the agonist ET-1 or the antagonist BQ-123 (Figure 5)). Of note, neither of these concentrations of ET-1 produced a detectable increase of [Ca2+]in in HEK 293 cells (Figures 5E, 6A). The density of surface ET receptors in HEK 293, indicated by the lower mRNA and ET-1 binding sites, may be inadequate to trigger a detectable rise in [Ca+2]in.

Figure 5. ET-1 elicits ETA receptor mediated calcium transients in ND7/104 and HEK 293T but not HEK 293 cells.

A. Ratiometric calcium imaging of cell lines loaded with Fura-2. Addition of ET-1 (30 nM) to ND7/104 (A) or HEK 293T (C) cells caused an increase in [Ca]in. This effect is blocked by the ETA selective antagonist BQ-123 (B, D). In HEK 293 cells (E) ET-1 does not promote intracellular calcium mobilization. Each panel represents traces from one single cell representative of the field. Cells were rinsed with Ringer prior to ATP addition.

Figure 6. ET-1 elicits calcium transients in ND7/104 and HEK 293T but not HEK 293 cells.

A. Ratiometric calcium imaging on ND7/104 or HEK 293T cells loaded with Fura-2AM. Addition of ET-1 30 nM (small checkers bars) or 100 nM (large checkers bars) to ND7/104 or HEK 293T cells caused an increase in [Ca]in. However this effect was not observed in HEK 293 cells which show lower message and binding for both ETA and ETB receptors. Values are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with bonferroni correction.

B: Ratiometric calcium imaging on ND7/104 (small checkers bars) or HEK 293T (large checkers bars) cells loaded with Fura-2AM and preincubated with BQ-123 (50 nM), BQ-788 (100 and 200 nM) or IRL-2500 (50 and 100 nM) and then exposed to ET-1 (30 nM) alone or in combination with the appropriate antagonist. The ETA receptor selective antagonist BQ-123 completely prevented the ET-1 mediated calcium response, while the ETB selective antagonists BQ-788 and IRL-2500 were without effect. Note that the application of the antagonist alone did not significantly alter the basal intracellular calcium levels (not shown). Values are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with bonferroni correction (*** p< 0.001, * p< 0.05).

To investigate which receptor subtype is responsible for the ET-1 stimulated rise in [Ca2+] in, selective antagonists were applied first alone and subsequently in combination with 30 nM ET-1 on the same coverslip. Recorded responses (Figure 5) show that none of the antagonists applied alone triggered a rise in [Ca+2]in (data not shown). Furthermore, the ET-1 stimulated calcium increase was blocked by 50 nM BQ-123 but not affected by BQ-788 (100 nM) nor by IRL-2500 (50 nM), two potent ETB-selective antagonists (Figure 6B). Therefore, in these cells endogenous ETA receptors appear to be responsible for the rise in intracellular calcium. Note that at higher concentration IRL-2500 (100 nM) partially blocked the response to ET-1 (30 nM), probably as a result of its lack of selectivity for ETB receptors at that concentration.

These findings confirm the ETA receptor dependence of calcium responses in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells. Although both ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells also have ETB receptors, these receptors were present at a lower level and may therefore not be sufficiently abundant to support a calcium response. The concept of a threshold expression for ET receptor in calcium mobilization is supported by the lack of an ET-1 calcium response in HEK 293 cells, which have 10-fold lower levels of both ETA and ETB receptors (Table 1) and which lack any ET-1 – induced intracellular calcium increases.

In a context where accumulating evidence points to GPCR expression levels as a determining factor in the selectivity of coupling to G proteins, and signaling pathway engagement [44,45], these cells represent a useful tool. This important point is further emphasized by the fact that these cells are often used for heterologous expression studies [43] as well as by a recent report demonstrating that, when over-expressed in CHO cells, ETA receptors have the ability to recruit additional G proteins [46].

3.3. Activation of the endogenous ETB receptor with selective agonists does not trigger a rise in intracellular calcium concentration

To confirm the lack of an ETB receptor contribution to the ET-1 mediated calcium signal in these cells, we tested whether activation of ETB receptors with selective agonists could trigger a rise in intracellular calcium. First, cells were stimulated with 50 nM BQ-3020, a potent and highly selective ETB receptor agonist. Subsequently, we used IRL-1620, also a highly selective ETB receptor agonist. Finally, we used the highly ETB-selective sarafotoxin 6c, a 21 amino acid peptide agonist isolated from snake venom with a structure similar to ET-1. As shown in Figure 7, none of these agonists elicited a rise of [Ca+2]in, thus corroborating the results obtained with ETB selective antagonists.

Figure 7. ETB selective agonists do not elicit calcium transients in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells.

Ratiometric calcium imaging on ND7/104 (white bars) and HEK 293T (black bars) cells loaded with Fura-2AM. Cells did not respond to the application of the ETB selective agonists sarafotoxin 6 c (50 and 1000 nM), IRL-1620 (100 and 1000 nM) or BQ-3020 (100 and 1000 nM). Values are mean ± SEM of 2 (high concentration) or 3 (low concentration) independent experiments analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with bonferroni correction (*** p<0.001).

3.4. Down-regulation of ETB mRNA levels in HEK 293T cells does not alter the intracellular calcium release triggered by ET-1

Since ETB receptors have been proposed to interact with ETA receptors through the formation of heterodimers [34,36], we sought to analyze any potential contribution of ETB receptors to the coupling of ETA receptors to calcium’s increase. To do so, HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with either siRNA targeting the human ETB receptor or a “control” pool of non-targeting siRNA. Forty eight hours following transfection the cells underwent calcium imaging. Simulation of the cells with ET-1 (30 nM) elicited a calcium transient in both siRNA-treated and control cells (Figure 8A) suggesting that ETB is not necessary for the coupling of ETA to the calcium pathway. This is consistent with previous findings in HEK 293 cells showing that ET-1 can trigger a calcium response in HEK cells transfected with only ETA receptors [33]. ETA and ETB mRNA expression levels in the cells used for calcium imaging were determined by quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR). While mRNA levels for ETB were substantially reduced in these cells (p< 0.01), those for ETA were unchanged as compared to the cells transfected with the non-targeting pool siRNAs (Figure 8B). These results furthe confirm that ETB receptors do not influence coupling of ETA receptors to intracellular calcium release in these cells.

Figure 8. The calcium response remains unchanged following down regulation of ETB transcript levels.

A. Ratiometric calcium imaging on HEK 293T cells transfected with control (NTP) or ETB siRNA (large checkers and stripes). Cells were loaded with Fura-2AM 48 hrs following transfection. The response to ET-1 (30 nM) is not significantly different between the two treatments (p>0.05). Values are mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments analyzed by student t-test versus control.

B. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of ETA and ETB transcript abundance in HEK 293T cells transfected with ETB specific SiRNA. Treatment of HEK 293T cells with ETB specific siRNA reduced mRNA levels of ETB, but not ETA receptors. Values for ETA and ETB are normalized to cyclophilin A expression levels and expressed in arbitrary units as the mean ± SEM of a biological sample performed in triplicate. 1 ETB siRNA and 2 ETB siRNA each represent an independent experiment in which cells were transfected with ETB siRNA. NTP represent the control experiment which used a non-targeting pool of siRNA. (** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, student t-test versus NTP).

3.5. ET-1 elicits a release of calcium from intracellular stores in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cell via Phospholipase C and Gαq/11

To clarify the intracellular mechanisms responsible for the rise of [Ca2+]in upon ET-1 stimulation in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells, we used selective inhibitors of potential signaling components downstream of the receptor. First, we sought to determine whether the rise of intracellular free calcium concentration resulted from Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or from a Ca2+ influx through voltage-independent Ca2+-permeable cation channels. When calcium imaging experiments were performed in the absence of extracellular calcium the response to ET-1 was not diminished in ND7/104 or in HEK 293T cells (Figure 9), implying that the elevated intracellular Ca2+ is released from the ER, most probably following activation of IP3 receptors. This independence from extracellular calcium was also the case for the ATP response, indicating that in these cells endogenous P2Y receptors are involved. RT-PCR with primers specific for P2Y1, a receptor previously reported to be endogenously expressed in HEK 293 cells [47], confirmed the presence of this receptor in our HEK 293T, HEK 293 and ND7/104 cultures (data not shown). Note that the elevated response ratio of ET-1:ATP recorded in ND7/104 cells is due to a lower ATP response in the absence of extracellular calcium, as opposed to a larger response to ET-1. One likely explanation for this effect could come from the fact that P2X receptors contribute to the calcium response in these cells.

Figure 9. Effects of selective second messenger pathway modulators on the Ca2+ response to ET-1 in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells.

Ratiometric calcium imaging on ND7/104 (white bars) and HEK 293T (black bars) cells loaded with Fura-2AM. The absence of extracellular calcium or pretreatment with PTX did not affect the response while U73122, an inhibitor of PLC activity, prevented a rise of intracellular calcium concentration upon ET-1 stimulation. Values are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with bonferroni correction (*** p< 0.001, * p< 0.05).

To further confirm that endothelin receptors are coupled to phospholipase C (PLC) activation, we examined the effects of the selective PLC inhibitor U73122. Cells were pretreated for 30 minutes with 10 µM U73122 prior to stimulation with ET-1 (30 nM). Under these conditions we observed a complete inhibition of the calcium transient induced by ET-1 in both cell lines (Figure 9), indicating that endothelin receptors are coupled to phospholipase C activation in these cells. The calcium response to ATP was also abrogated by U73122 in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells suggesting that P2Y receptors are operating via PLC as well. (Due to the absence of a response to ATP in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells in the presence of U73122, the ET-1 response was standardized to that of ionomycin instead of ATP). Note that in ND7/104 cells, U73122 does not inhibit the response elicited by bradykinin, suggesting that its inhibitory action is not through some non-selective effect (data not shown).

G protein-coupled receptors such as the ETA and ETB receptors can stimulate phospholipase C’s activity through two mechanisms [28]. One mechanism involves the G protein α-subunit Gαq/11 while the other mechanism implicates the βγ subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein, usually those interacting with Gαi subunits. To discriminate between these two possibilities, cells were pre-treated for 24–36 hrs with 10 ng/ml pertussis toxin (PTX) prior to stimulation with ET-1 (30 nM). PTX differentially inactivates Gαi while leaving Gαq/11 signaling unaffected. As illustrated in Figure 9, the PTX treatment did not affect the response to ET-1, implying that in these cell lines ET-1 mediates its effect through Gαq/11.

Altogether, these results demonstrate that ETA receptor activation leads to the release of calcium from internal stores in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells through the Gαq/11 - PLC signaling pathway. It is likely that these steps also underlie the BQ-123-sensitive intracellular calcium increase emanating from intracellular stores recorded in freshly dissociated mouse DRG neurons exposed to 10 nM ET-1, a step that leads to TRPV1 potentiation [24]. Interestingly, Nishimura et al., reported that in HEK 293T cells Ric-8A, a GTP exchange factor for Gαq, works as a positive regulator of ATP- and ET-1-induced intracellular calcium mobilization and of ERK activation [42]. Since Ric-8A is present in the nervous system in mice [48] it will be interesting to test whether this factor modulates ET-1 signaling in DRG neurons in an ETA-selective manner. In addition, several other regulatory proteins in complex with Gαq [49] might also participate in the modulation of the ETA mediated pain signaling pathway in DRG neurons. One promising candidate is the G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2). It is a well known modulator of GPCR activity [50] that is present in about 50 % of DRG neurons. GRK2 has been shown to have a functional role in increased sensitivity of nociceptors elicited by IL-1β [51] and may similarly participate in nociceptor sensitization mediated by ET-1.

3.6. ET-1 does not engage the Epac pathway to trigger the release of calcium from intracellular stores in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells

It was previously reported that in HEK 293 cells cAMP is able to elicit the release of calcium from intracellular stores through a pathway involving the cAMP-dependent RAP guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor known as Epac (exchange protein directly activated by cAMP). RAP activation ultimately leads to activation of phospholipase Cε which in turn produces IP3 and opens IP3 receptors on the ER [52]. Since U73122 is a broadly acting PLC blocker, the use of this compound does not allow discrimination between activation through Gαq/11 and Gαs, both of which activate PLCs. To discriminate between these two possibilities, we first sought to determine whether ET-1 (0.3 nM to 300 nM) elicited a rise in cAMP levels in these cells using an Elisa-based cell assay to monitor intracellular levels of cAMP. Under these conditions we did not record a rise of intracellular cAMP in either ND7/104 or HEK 293T cells (Figure 10A), whilst a strong activator of adenylate cyclase, forskolin (10 µM), produced a consistent and robust cAMP accumulation (data not shown). Next we tested whether blocking the cAMP pathway in HEK 293T and ND7/104 cells would affect negatively the calcium transient elicited by ET-1 (30 nM). First, cells were preincubated for 18hrs with 100 ng/ml cholera toxin (CTX), known to uncouple the receptor from Gαs. This treatment did not significantly alter the calcium transient elicited by ET-1 (30 nM) compared to untreated cells, in the presence or absence of extracellular calcium (Figure 10B). Additional experiments using the adenylate cyclase inhibitor MDL-12,330A (50 µM), which led to the same outcome (Figure 10B) further argue that ET-1-induced calcium responses in HEK 293T and ND7/104 cells are not mediated through the Epac pathway.

Figure 10. Effects of increasing concentrations of ET-1 and cAMP pathway modulators on intracellular cAMP accumulation and calcium release respectively in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells.

A. cAMP accumulation in response to increasing concentrations of ET-1 in ND7/104 (circles) and HEK 293T (squares) cells. Cells were seeded in 96 well plates and 24–36 hrs later challenged with increasing concentrations of ET-1 for 10 minutes at 37 °C. As a control some cells were stimulated with forskolin (10 µM), a direct activator of adenylate cyclase activity, under the same conditions. cAMP was measured using an enzyme immunoassay kit. None of the ET-1 concentrations tested produced a significant effect on intracellular cAMP accumulation whereas forskolin was a potent stimulator with 71.3 ± 6.2 fmol/µg and 15.5 ± 2.5 fmol/µg in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells respectively. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

B. Ratiometric calcium imaging on ND7/104 (small checkers) and HEK 293T (large checkers) cells loaded with Fura-2AM. Pretreatment of the cells with CTX (100 ng/ml) for 24–36 hrs or MDL 12,330A (50 µM) five minutes before ET-1 (30 nM) stimulation did not affect negatively the rise of intracellular calcium concentration elicited by ET-1 in a significant way. The boost recorded following MDL 12,3330A preincubation in ND7/104 cells is caused by a markedly diminished response to ATP in these cells. This phenomenon is also observed in absence of extracellular calcium. Note that MDL 12,330A alone did not produce a significant effect on basal intracellular calcium levels (not shown). Values are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with bonferroni correction (*** p< 0.001, * p< 0.05).

Note that the statistically significant (p < 0.05) boost in the response ratio recorded in ND7/104 cells under zero extracellular calcium conditions is explained by a diminished response to ATP following this treatment rather than an increased response to ET-1. In these cells pretreatment with MDL 12,330A had a similar effect on the ATP response. Note that application of MDL 12,330A (50 µM) alone did not elicit a significant rise of [Ca2+]in above baseline levels (data not shown).

ETA and ETB heterologously expressed in CHO cells have been reported to couple to Gαs and GαI, respectively [53]. If we make the assumption that endogenous ET receptors in HEK 293T and ND7/104 cells are coupled to the same G-proteins, then the net effect of their simultaneous activation on intracellular cAMP effect might be close to zero as these receptors would antagonize each other. Under these conditions activation of the Epac pathway by ET-1 would be unlikely.

4. Conclusion and perspectives

In conclusion, our data reveal the crucial role of endogenous ETA and Gαq/11 in the ET-1-evoked calcium transient in ND7/104 and HEK 293T cells. If these findings are validated in pain models in vivo then these cell lines will become valuable tools for the screening and development of therapeutic compounds targeting this pain signaling pathway. In addition, ETA and ETB receptors have been recently reported to interact through their carboxy-terminal regions with a number of accessory proteins regulating dimerization, degradation, and sub-compartment localization [54–56]. It will be interesting to study if these accessory proteins modulate calcium signaling by endothelin receptors as well.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to A. Porcher and T. Berta for support with Excel and qPCR experiments respectively. We are indebted to J. Montgomery and P. Patterson (Caltech, CA) for help with siRNA experiments. Finally we would like to thank Mr S. Shrestha for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y, Yazaki Y, Goto K, Masaki T. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332:411–415. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luscher TF, Barton M. Endothelins and endothelin receptor antagonists: Therapeutic considerations for a novel class of cardiovascular drugs. Circulation. 2000;102:2434–2440. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.19.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kedzierski RM, Yanagisawa M. Endothelin system: The double-edged sword in health and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:851–876. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton M, Yanagisawa M. Endothelin: 20 years from discovery to therapy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86:485–498. doi: 10.1139/Y08-059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arai H, Hori S, Aramori I, Ohkubo H, Nakanishi S. Cloning and expression of a cdna encoding an endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:730–732. doi: 10.1038/348730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Miyazaki H, Kimura S, Goto K, Masaki T. Cloning of a cdna encoding a non-isopeptide-selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:732–735. doi: 10.1038/348732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Masaki T. Molecular characterization of endothelin receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:103–108. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davenport AP. International union of pharmacology Xxix. Update on endothelin receptor nomenclature. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:219–226. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khodorova A, Montmayeur JP, Strichartz G. Endothelin receptors and pain. J Pain. 2009;10:4–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mujenda FH, Duarte AM, Reilly EK, Strichartz GR. Cutaneous endothelin-a receptors elevate post-incisional pain. Pain. 2007;133:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stosser S, Agarwal N, Tappe-Theodor A, Yanagisawa M, Kuner R. Dissecting the functional significance of endothelin a receptors in peripheral nociceptors in vivo via conditional gene deletion. Pain. 2010;148:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gokin AP, Fareed MU, Pan HL, Hans G, Strichartz GR, Davar G. Local injection of endothelin-1 produces pain-like behavior and excitation of nociceptors in rats. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5358–5366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05358.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pomonis JD, Rogers SD, Peters CM, Ghilardi JR, Mantyh PW. Expression and localization of endothelin receptors: Implications for the involvement of peripheral glia in nociception. J Neurosci. 2001;21:999–1006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-00999.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters CM, Lindsay TH, Pomonis JD, Luger NM, Ghilardi JR, Sevcik MA, Mantyh PW. Endothelin and the tumorigenic component of bone cancer pain. Neuroscience. 2004;126:1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berti-Mattera LN, Gariepy CE, Burke RM, Hall AK. Reduced expression of endothelin b receptors and mechanical hyperalgesia in experimental chronic diabetes. Exp Neurol. 2006;201:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Z, Davar G, Strichartz G. Endothelin-1 (et-1) selectively enhances the activation gating of slowly inactivating tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium currents in rat sensory neurons: A mechanism for the pain-inducing actions of et-1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6325–6330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06325.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng B, Strichartz G. Endothelin-1 raises excitability and reduces potassium currents in sensory neurons. Brain Res Bull. 2009;79:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caterina MJ, Julius D. The vanilloid receptor: A molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawamata T, Ji W, Yamamoto J, Niiyama Y, Furuse S, Omote K, Namiki A. Involvement of transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 in endothelin-1-induced pain-like behavior. Neuroreport. 2009;20:233–237. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32831befa5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawamata T, Ji W, Yamamoto J, Niiyama Y, Furuse S, Namiki A. Contribution of transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 to endothelin-1-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Neuroscience. 2008;154:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balonov K, Khodorova A, Strichartz GR. Tactile allodynia initiated by local subcutaneous endothelin-1 is prolonged by activation of trpv-1 receptors. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:1165–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.da Cunha JM, Rae GA, Ferreira SH, Cunha Fde Q. Endothelins induce etb receptor-mediated mechanical hypernociception in rat hindpaw: Roles of camp and protein kinase c. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;501:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motta EM, Chichorro JG, Rae GA. Role of et(a) and et(b) endothelin receptors on endothelin-1-induced potentiation of nociceptive and thermal hyperalgesic responses evoked by capsaicin in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2009;457:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto H, Kawamata T, Ninomiya T, Omote K, Namiki A. Endothelin-1 enhances capsaicin-evoked intracellular ca2+ response via activation of endothelin a receptor in a protein kinase cepsilon-dependent manner in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience. 2006;137:949–960. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plant TD, Zollner C, Kepura F, Mousa SS, Eichhorst J, Schaefer M, Furkert J, Stein C, Oksche A. Endothelin potentiates trpv1 via eta receptor-mediated activation of protein kinase c. Mol Pain. 2007;3:35. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase c and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. Faseb J. 1995;9:484–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou QL, Strichartz G, Davar G. Endothelin-1 activates et(a) receptors to increase intracellular calcium in model sensory neurons. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3853–3857. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tykocki NR, Watts SW. The interdependence of endothelin-1 and calcium: A review. Clin Sci (Lond) 2010;119:361–372. doi: 10.1042/CS20100145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (rest) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time pcr. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time rt-pcr. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thakali K, Galligan JJ, Fink GD, Gariepy CE, Watts SW. Pharmacological endothelin receptor interaction does not occur in veins from et(b) receptor deficient rats. Vascul Pharmacol. 2008;49:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harada N, Himeno A, Shigematsu K, Sumikawa K, Niwa M. Endothelin-1 binding to endothelin receptors in the rat anterior pituitary gland: Possible formation of an eta-etb receptor heterodimer. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2002;22:207–226. doi: 10.1023/A:1019822107048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gregan B, Jurgensen J, Papsdorf G, Furkert J, Schaefer M, Beyermann M, Rosenthal W, Oksche A. Ligand-dependent differences in the internalization of endothelin a and endothelin b receptor heterodimers. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27679–27687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans NJ, Walker JW. Sustained ca2+ signaling and delayed internalization associated with endothelin receptor heterodimers linked through a pdz finger. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86:526–535. doi: 10.1139/Y08-050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans NJ, Walker JW. Endothelin receptor dimers evaluated by fret, ligand binding, and calcium mobilization. Biophys J. 2008;95:483–492. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.119206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gregan B, Schaefer M, Rosenthal W, Oksche A. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis reveals the existence of endothelin-a and endothelin-b receptor homodimers. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44 Suppl 1:S30–S33. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000166218.35168.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dai X, Galligan JJ. Differential trafficking and desensitization of human et(a) and et(b) receptors expressed in hek 293 cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:746–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chichorro JG, Zampronio AR, Cabrini DA, Franco CR, Rae GA. Mechanisms operated by endothelin eta and etb receptors in the trigeminal ganglion contribute to orofacial thermal hyperalgesia induced by infraorbital nerve constriction in rats. Neuropeptides. 2009;43:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nambi P, Pullen M, Kincaid J, Nuthulaganti P, Aiyar N, Brooks DP, Gellai M, Kumar C. Identification and characterization of a novel endothelin receptor that binds both eta- and etb-selective ligands. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:582–589. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nambi P, Elshourbagy N, Wu HL, Pullen M, Ohlstein EH, Brooks DP, Lago MA, Elliott JD, Gleason JG, Ruffolo RR., Jr Nonpeptide endothelin receptor antagonists. I. Effects on binding and signal transduction on human endothelina and endothelinb receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:755–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Angelova K, Ergul A, Narayan P, Puett D. Endothelin binding to ng108-15 cells: Evidence for conventional eta and etb receptor subtypes and super-high affinity binding components. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 1996;42:1243–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishimura A, Okamoto M, Sugawara Y, Mizuno N, Yamauchi J, Itoh H. Ric-8a potentiates gq-mediated signal transduction by acting downstream of g protein-coupled receptor in intact cells. Genes Cells. 2006;11:487–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vetter I, Lewis RJ. Characterization of endogenous calcium responses in neuronal cell lines. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:908–920. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kenakin T. Differences between natural and recombinant g protein-coupled receptor systems with varying receptor/g protein stoichiometry. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:456–464. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perez DM, Karnik SS. Multiple signaling states of g-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:147–161. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horinouchi T, Asano H, Higa T, Nishimoto A, Nishiya T, Muramatsu I, Miwa S. Differential coupling of human endothelin type a receptor to g(q/11) and g(12) proteins: The functional significance of receptor expression level in generating multiple receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;111:338–351. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09233fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fischer W, Wirkner K, Weber M, Eberts C, Koles L, Reinhardt R, Franke H, Allgaier C, Gillen C, Illes P. Characterization of p2×3, p2y1 and p2y4 receptors in cultured hek293-hp2×3 cells and their inhibition by ethanol and trichloroethanol. J Neurochem. 2003;85:779–790. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tonissoo T, Meier R, Talts K, Plaas M, Karis A. Expression of ric-8 (synembryn) gene in the nervous system of developing and adult mouse. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3:591–594. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shankaranarayanan A, Thal DM, Tesmer VM, Roman DL, Neubig RR, Kozasa T, Tesmer JJ. Assembly of high order g alpha q-effector complexes with rgs proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34923–34934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805860200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. The role of beta-arrestins in the termination and transduction of g-protein-coupled receptor signals. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:455–465. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von Banchet GS, Fischer N, Uhlig B, Hensellek S, Eitner A, Schaible HG. Molecular effects of interleukin-1beta on dorsal root ganglion neurons: Prevention of ligand-induced internalization of the bradykinin 2 receptor and downregulation of g protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;46:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmidt M, Evellin S, Weernink PA, von Dorp F, Rehmann H, Lomasney JW, Jakobs KH. A new phospholipase-c-calcium signalling pathway mediated by cyclic amp and a rap gtpase. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1020–1024. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takagi Y, Ninomiya H, Sakamoto A, Miwa S, Masaki T. Structural basis of g protein specificity of human endothelin receptors. A study with endothelina/b chimeras. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10072–10078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chahdi A, Sorokin A. The role of beta(1) pix/caveolin-1 interaction in endothelin signaling through galpha subunits. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1330–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee HJ, Chun M, Kandror KV. Tip60 and hdac7 interact with the endothelin receptor a and may be involved in downstream signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16597–16600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nishimoto A, Lu L, Hayashi M, Nishiya T, Horinouchi T, Miwa S. Jab1 regulates levels of endothelin type a and b receptors by promoting ubiquitination and degradation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1616–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]