Abstract

Objective To examine the rise in the rate of involuntary admissions for mental illness in England that has occurred as community alternatives to hospital admission have been introduced.

Design Ecological analysis.

Setting England, 1988-2008.

Data source Publicly available data on provision of beds for people with mental illness in the National Health Service from Hospital Activity Statistics and involuntary admission rates from the NHS Information Centre.

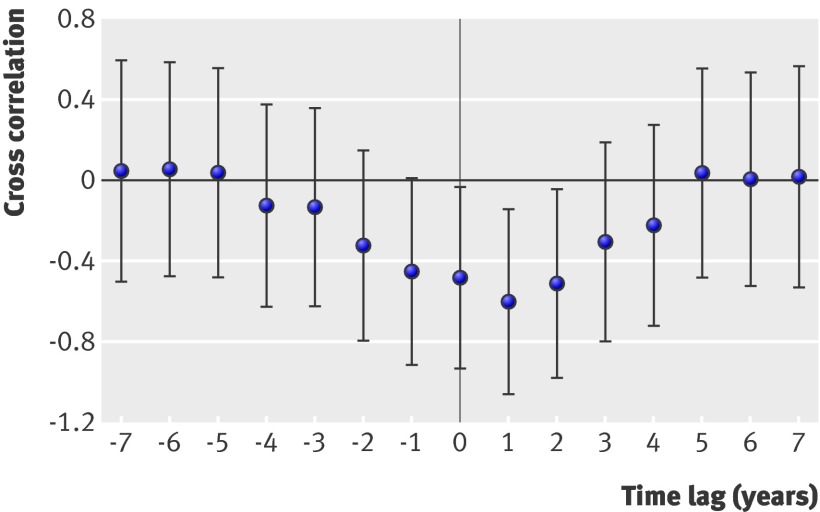

Main outcome measures Association between annual changes in provision of mental illness beds in the NHS and involuntary admission rates, using cross correlation. Partial correlation coefficients were calculated and regression analysis carried out for the time lag (interval) over which the largest association between these variables was identified.

Results The rate of involuntary admissions per annum in the NHS increased by more than 60%, whereas the provision of mental illness beds decreased by more than 60% over the same period; these changes seemed to be synchronous. The strongest association between these variables was observed when a time lag of one year was introduced, with bed reductions preceding increases in involuntary admissions (cross correlation −0.60, 95% confidence interval −1.06 to −0.15). This association increased in magnitude when analyses were restricted to civil (non-forensic) involuntary admissions and non-secure mental illness beds.

Conclusion The annual reduction in provision of mental illness beds was associated with the rate of involuntary admissions over the short to medium term, with the closure of two mental illness beds leading to one additional involuntary admission in the subsequent year. This study provides a method for predicting rates of involuntary admissions and what may happen in the future if bed closures continue.

Introduction

Closure of beds for people with mental illness in high income countries has been part of policies to deinstitutionalise the care of people with mental illness, and there have been calls for this to be replicated in low and middle income countries where scarce resources are concentrated in large asylums.1 However, the rates of involuntary admissions have been increasing in some western European countries,2 including England since the introduction of the Mental Health Act in 1983.3 This trend has continued despite the development of a range of community based services such as community mental health teams, assertive outreach, crisis resolution home treatment, and early intervention services. Most of these probably reduce voluntary rather than involuntary admissions.4 5 6 7

This increase in the use of compulsory detention sits uneasily with patients and professionals equally.8 9 10 11 12 It is also a source of concern to service commissioners and service providers, given the high costs of inpatient care. The increasing rate of involuntary treatment represents a major financial obstacle to further investment in community services, particularly at times of austerity. Understanding the determinants of this trend is therefore imperative.

Different explanations for the increase in involuntary admissions have been proposed, including secular increases in the use of illicit drugs and alcohol. But empirical evidence is limited. An alternative hypothesis is that the increase in involuntary admissions in England is due to bed shortages arising from reductions in the numbers of mental health beds (and especially long stay or “rehabilitation” beds) dating back to the 1950s.13 An ecological study across eight hospital trusts in England provided some support for this view, finding that the rate of involuntary admissions was associated with delays in accessing inpatient beds (as well as with socioeconomic deprivation and the size of ethnic minority populations).14

In the present economic climate, further closure of inpatient beds seems the most likely strategy for funding improvements in community based mental health services. Although this is in keeping with providing care in the least restrictive setting and as near to home as possible, there is little evidence to guide the relative and absolute provision of short stay, long stay, and secure mental illness beds in the National Health Service.

We tested the hypothesis that between 1988 and 2008 there was a direct temporal association between the reduction in provision of mental illness beds in the NHS in England and change in the rate of involuntary admission under the Mental Health Act, after controlling for secular trends in both. If this hypothesis is supported, it could be used to anticipate and model the possible effect of any future bed closures on rates of involuntary inpatient treatment.

Methods

We carried out an ecological analysis of publicly available administrative data to investigate the associations between changes in the provision of mental illness beds and the rate of involuntary admissions within the NHS in England between 1988 and 2008.

Rate of involuntary admissions

Data on involuntary admissions to NHS hospitals under the Mental Health Act were obtained from the NHS Information Centre.15 We analysed involuntary admissions under different sections of the act (box): admissions for assessment (section 2) and admissions for treatment (section 3) under part II of the act; and all forensic sections under part III. We excluded emergency sections that permitted brief detention for assessment (sections 136 and 4) if patients then became voluntary inpatients or were discharged after assessment; however, we included these emergency sections (136 and 4) if patients were subsequently detained under sections 2 or 3. These detentions were combined with admissions directly under sections 2 or 3 to calculate the number of civil (non-forensic) involuntary admissions.

Relevant parts and sections of the Mental Health Act 1983

Part II: civil sections from the community

Section 2: admissions for assessment up to 28 days

Section 3: admissions for treatment up to six months and can be renewed

Section 4: admissions for assessment in an emergency, only when a second medical opinion is unavailable and where further delay in admission would place patients or others at risk. Under the code of practice, section 4 must either be converted to sections 2 or 3 within 72 hours of admission or the section 4 must be discharged

Part III: forensic sections from custody

These include sentenced and remanded prisoners who need assessment or treatment in hospital, or those appearing in court who are diverted to hospital rather than being sent to prison

Part X: place of safety orders

Section 136: removal of an individual from a public place by police to a place of safety for assessment. Does not cover admissions to hospital

We also excluded detentions of voluntary patients who were already in hospital. As we were testing the a priori hypothesis that increased detention rates were due to bed closures (that is, that involuntary admissions were a “last resort” when patients were too ill to be cared for in any other way), detention for days to weeks after voluntary admission was clearly not part of this hypothesis as the admission has already occurred. Although excluding these cases underestimates the total number of detentions, it restricts the study sample to detentions that co-occur with admission and so rely on available beds.

We calculated the rates of involuntary admissions per 100 000 adult population by dividing the number of involuntary admissions by the population of England aged 16 and over in that year. Change throughout England over time was determined by comparing health authority data from 1989/90 with that from 2003/4. The health authorities changed from regional to strategic health authorities during the study period: between 1974 and 1996 the 14 regional health authorities changed to 28 strategic health authorities, which were then reduced to 10 in 2006.

The number of involuntary admissions in each regional health authority was only available in 1989/90. To calculate rates we used the adult population for these health authorities for 1991/2. The number of involuntary admissions in each of the 28 strategic health authorities was available between 1998/9 and 2003/4. We calculated the rates for each strategic health authority in 2003/4 using the adult population in the same year. All rates of involuntary admissions, whether nationally or regionally, are reported per 100 000 adult population (≥16 years).

The former regional health authorities do not, however, map readily onto the boundaries of the strategic health authorities. To compare rates in 1989/90 with those in 2003/4 we therefore aggregated the health authorities into six groupings that represented the best fit: North, West Midlands, East Midlands, East Anglia, South East, and South West and Central England. The success of mapping at this level is shown by the correspondence of population sizes, which compare well between the two years (table 1).

Table 1.

Population and rate of NHS civil involuntary admissions for mental illness in six areas of England in 1989 and 2003

| Area of England | Population aged ≥16 (000s) | Civil involuntary admissions per 100 000 population aged ≥16 | % change in rate of civil involuntary admissions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 (14 RHAs) | 2003 (28 SHAs) | 1989 | 2003 | |||

| North | 10 575* | 10 484† | 37.5 | 54.6 | 46 | |

| West Midlands | 4225 | 4240‡ | 34.7 | 62.1 | 79 | |

| East Midlands | 3817§ | 4443¶ | 31.9 | 47.7 | 50 | |

| East Anglia | 1701 | 1800** | 33.1 | 51.9 | 57 | |

| South West and South Central | 7195†† | 7201‡‡ | 34.2 | 55.3 | 62 | |

| South East | 11 412§§ | 11 885¶¶ | 36.2 | 75.5 | 109 | |

| England | 38 925 | 40 053 | 36.2 | 60.7 | 68 | |

RHAs=regional health authorities; SHAs=strategic health authorities.

*Northern; Yorkshire; Mersey; and North Western.

†Northumberland, Tyne, and Wear; County Durham and Tees Valley; North and East Yorkshire and Northern Lincolnshire; West Yorkshire; Cumbria and Lancashire; Greater Manchester; and Cheshire and Merseyside.

‡Shropshire and Staffordshire; Birmingham and the Black Country; and Coventry, Warwickshire, Herefordshire, and Worcestershire.

§Trent.

¶Trent; Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, and Rutland; and South Yorkshire.

**Norfolk, Suffolk, and Cambridgeshire.

††Wessex; Oxford; and South Western.

‡‡Thames Valley; Hampshire and Isle of Wight; Avon, Gloucestershire, and Wiltshire; Dorset and Somerset; and South West Peninsula.

§§North West Thames; North East Thames; South East Thames; and South West Thames.

¶¶Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire; Essex; North West London; North Central London; North East London; South East London; South West London; Kent and Medway; and Surrey and Sussex.

Provision of mental illness beds

We obtained the number of inpatient beds for mental illness in the NHS for each year during the study period from Hospital Activity Statistics,16 giving the average number of NHS beds for each financial year by wards and types of illness. We chose the mental illness sector only, excluding acute, geriatric, learning disability, maternity, and day bed sectors. Data were available for beds in short stay wards (all ages; patients intended to stay <1 year), long stay wards (all ages; patients intended to stay ≥1 year), and secure (forensic) wards.

To calculate the number of non-secure beds for mental illness we combined long stay and short stay beds. By dividing the number of beds by the population aged 16 years and older we calculated the rate of bed provision per 100 000 adult population. As data were not available separately on the number of mental illness beds for children before 1996 we used all mental illness bed types. However, we estimate that such beds for children only accounted for between 1% and 2% of all mental illness beds during the study period. Data were not available on numbers of mental illness beds in each of the regional health authorities. Therefore it was not possible to calculate changes in bed provision in the six areas described in the involuntary admissions section.

Statistical analysis

We created a single data file with data on beds and involuntary admissions combined for all 21 study years. For each year we recorded the provision of mental illness beds and rate of involuntary admissions. We also recorded the corresponding data on beds and involuntary admissions for previous and subsequent years.

Cross lagged longitudinal correlation analysis was applied to 21 data points comprising yearly information on involuntary admission rates and bed provision for the two decades under study (1988-2008). Both time series showed clear trends. To calculate the annual change (20 data points) we carried out de-trending by introducing one degree of differencing. All statistical analyses reported were carried out on raw data. To reduce the amount of noise in the datasets, however, we used data smoothing with the T4253H algorithm,17 thus ensuring easy interpretation of the figures illustrating the patterns of change.

We used cross correlation to investigate associations between annual change in bed provision and annual change in the rate of admissions at yearly time lags. This is a form of pattern recognition used outside of medicine, such as in economics, and within medicine (for example, in circadian rhythm analysis). The method establishes how change in a variable in one period might best be matched or linked with changes in another variable. By assessing the fit of backward or forward shifts of one variable relative to the other, it is possible to test whether change in one precedes or follows change in the other variable. The analysis allows identification of the time lag, with the best fit indicated by the strongest correlation. Plotting these variables at the time lag of one year identified an extreme outlier (data from 1996), and inspection revealed that the change in involuntary admissions that year was anomalous, coinciding with a major change in the system of recording for involuntary admissions implemented in that year.18 As we could not ascertain the reliability of data from that year we excluded these from subsequent analyses.

We then calculated partial correlation coefficients for this time lag after controlling for autocorrelation (changes in bed provision in earlier years) and synchronous correlation (change in the rate of involuntary admissions in the same year). Regression analysis was carried out, with changes in the annual rate of involuntary admissions as the dependent variable. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS (version 17). Significance was set at P≤0.05.

Results

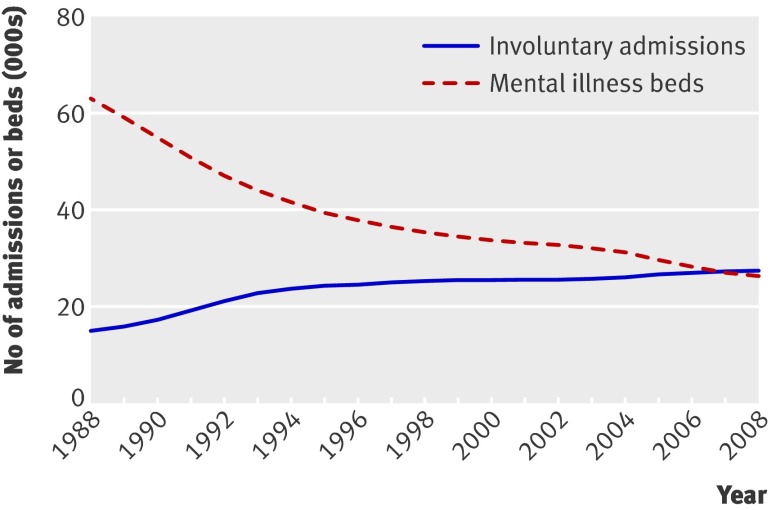

Between 1988 and 2008 the provision of mental illness beds in the NHS decreased by 62%, from 166.1 to 63.2 per 100 000 adults (total numbers decreased from 63 012 to 26 430; fig 1). During the same period the rate of involuntary admissions increased by 64%, from 40.2 to 65.7 per 100 000 adults per annum and exceeded bed provision by the end of the study period (total number of involuntary admissions increased from 15 234 to 27 468; fig 1). The decline in number of beds was accounted for by the reduction in the provision of non-secure beds (164.0 to 55.4; −66%). In contrast, the provision of secure beds increased during this time (2.2 to 7.9; 263%). The rise in involuntary admissions was due to an increase in the rate of civil involuntary admissions (36.3 to 62.5 per annum; 72%). Forensic involuntary admissions fluctuated and were lower at the end of the study period by 15% (from 3.9 to 3.3 per 100 000 adults).

Fig 1 Annual number of mental illness beds and involuntary admissions in National Health Service in England between 1998 and 2008 (smoothed data)

The rate of involuntary admissions increased throughout England. The rate of civil involuntary admissions in England in 1989/90 was 36.2 and this varied by more than twofold between the 14 regional health authorities (mean 34.7 (SD 8.3), range 21.3-51.8). By 2003/4 this rate had increased to 60.7 and varied by greater than fourfold between the 28 strategic health authorities (mean 61.2 (SD 18.6), range 25.8-115.9). The rate of civil involuntary admissions increased in all parts of the country, with the greatest increase in the South East and more modest increases in the North and East Midlands (table 1).

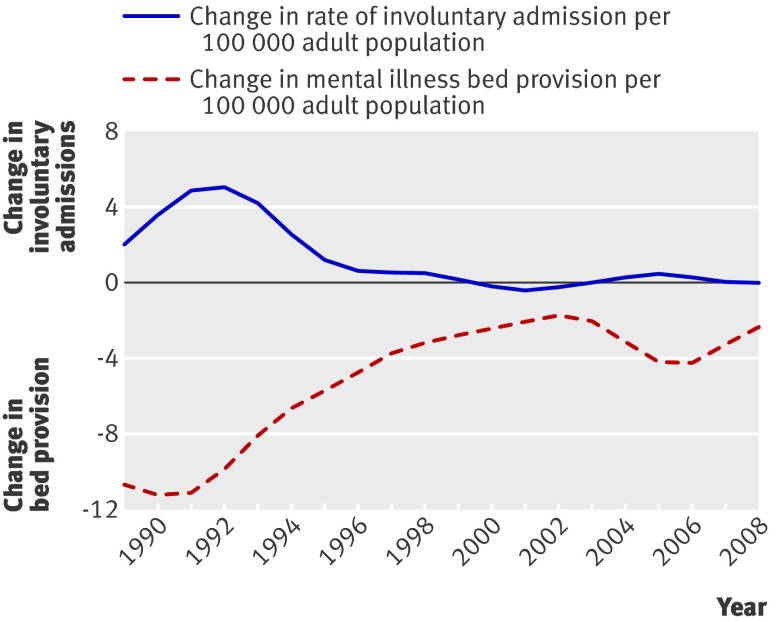

The annual changes in provision of mental illness beds and involuntary admission rates in England during the study period mirrored each other (fig 2), with two periods of accelerated change (1989 to 1994 and 2003 to 2007). Cross correlation of annual changes in provision of beds and involuntary admissions was strongest when a time lag of one year was introduced, with the annual change in the provision of mental illness beds significantly negatively correlated with the annual change in the rate of involuntary admissions in the subsequent year (r=−0.60, 95% confidence interval −1.06 to −0.15; fig 3).

Fig 2 Annual change in rates of involuntary admission and mental illness bed provision in National Health Service in England between 1988 and 2008 (smoothed data)

Fig 3 Cross correlation (95% confidence intervals) with time lags (7 years either way) between annual change in mental illness bed provision and annual change in rate of involuntary admission in National Health Service in England between 1988 and 2008. Positive lag relates changes in bed provision with subsequent changes in admission rates. Negative lag relates changes in bed provision with earlier changes in admission rates

Partial correlation between annual change in bed provision and rate of involuntary admissions a year later was statistically significant (r=−0.58; P=0.02) after controlling for autocorrelation (change in involuntary admission rate in the previous year) and synchronous correlation (change in bed provision in the same year). This correlation increased when only civil involuntary admissions were included in the analysis (r=−0.63; P=0.01), and was further strengthened when only non-secure beds were included (r=−0.69; P<0.01).

Regression analyses revealed that only changes in mental illness bed provision at a given and subsequent year, but not changes in the rate of involuntary admission in a given year, were associated with changes in the involuntary admission rate in the subsequent year to a statistically significantly extent. This applied particularly to civil involuntary admissions and non-secure beds. Regression coefficients for change in the provision of non-secure beds remained statistically significant after adjusting for changes in bed provision in the subsequent year and for the rate of involuntary admissions in a given year (table 2).

Table 2.

Regression analysis with annual change in rate of NHS civil involuntary admissions between 1988 and 2008 in England at subsequent year as dependent variable, and annual changes in non-secure mental illness bed provision, before and after adjusting for other variables in table

| Annual change in | Annual change in civil involuntary admissions in subsequent year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||

| B (SE) | P value | B (SE) | P value | |

| Non-secure beds in given year | −0.55 (0.10) | <0.001 | −0.49 (0.14) | 0.005 |

| Non-secure beds in subsequent year | −0.32 (0.14) | 0.039 | −0.08 (0.15) | 0.610 |

| Civil involuntary admissions in given year | 0.42 (0.24) | 0.100 | −0.01 (0.18) | 0.960 |

Outlier caused by change in method of recording involuntary admissions between 1995 and 1996 was excluded.

*Overall: F=8.5, r²=0.66, P=0.002.

Discussion

Since the 1980s the reduction in provision of beds for people with mental illness in the National Health Service in England has been closely associated with an increasing rate of involuntary admissions. Although year on year changes varied, an ineluctable reduction in mental illness beds occurred between 1988 and 2008, amounting to more than 60% of all bed provision. During the same period a greater than 60% increase took place in the rate of involuntary admissions each year. To our knowledge this is the first study to show that these processes are associated in a more than coincidental fashion.

The increase in involuntary admissions was mainly accounted for by a rapid rise in civil involuntary admissions between 1988 and 1992, followed by a more gradual increase from1996 to 2008. Interestingly, forensic admissions remained almost static across the study period and made up a progressively lower proportion of all involuntary admissions. Cross lagged correlation showed that the reduction in provision of mental illness beds in a given year (in particular, non-secure beds) was most strongly associated with increases in the rate of involuntary admission one year later. Regression analysis indicated that the closure of two mental illness beds was associated with one additional civil involuntary admission in the subsequent year.

Limitations of the study

Although the number of beds and involuntary admissions was large, the number of annual data points included in the analyses was relatively small (20 for cross lagged analyses). This limited the extent to which autocorrelations could be controlled for (we used only the rate of involuntary admissions in the preceding year), and may have increased the risk of false positive findings. Nevertheless, the conservative nature of our correlational and regression analyses in which we controlled for both autocorrelations and synchronous correlations—and the relative invariance of the resulting coefficients on doing so—would argue against significant over-estimation of effect sizes. Other limitations include the retrospective nature of the data and that they apply only to NHS admissions. We have previously shown that increases in admissions under the Mental Health Act to private facilities are also likely to be related to the reduction in NHS beds19; this may have led us to underestimate the impact of NHS bed closures on the total number of involuntary admissions in subsequent years.

Our findings on regional changes show that increases in the rate of involuntary admission have been countrywide. They also are in keeping with findings of significant variations between places,9 20 with the largest increase in the South East of England. Despite the great success and popularity of home treatment for acute mental health crises,10 it is clear that these services are hard to provide in places with high levels of socioeconomic deprivation and where family and other sources of community support are difficult to secure and sustain. These are also the areas with the largest ethnic minority populations and where services are most likely to be perceived as coercive and unsatisfactory.20 The present findings cannot tell us whether confounding (or reverse confounding) existed at the regional, trust, or hospital level. It is possible that the trends in beds and involuntary admissions are variable at these smaller spatial levels and also that the association between these might vary with local circumstances and context. In other words, although the ecological findings are valid and hold true, it is possible that some of the places with the most rapid reductions in bed numbers are not the same places where patients are increasingly likely to be admitted involuntarily.

Conclusions

Our findings support the hypothesis that changes in provision of mental illness beds in the NHS are associated with subsequent changes in the rate of involuntary admission over the short to medium term. This association particularly applied to civil involuntary admissions and the provision of non-secure beds, where there seems to be a dose-response relation. The nature of the dataset used for this analysis does not allow us to establish an empirical explanation for our findings. However, as it is unlikely that the 60% increase in involuntary admissions reflects an otherwise unreported dramatic increase in the prevalence of severe mental disorders in England, other hypotheses require future examination.

It is plausible that fewer available beds have led to more patients being detained in hospital. Delays in planned admissions or the non-availability of such admissions may lead to crises requiring involuntary admission. Similarly, delays in admitting patients may mean a worsening of their mental state and that when admission does occur it is more likely to be under the Mental Health Act rather than on a voluntary basis. It is possible that the rise in involuntary admissions may be due to relapses or deteriorations becoming more frequent as shorter admissions become the norm and patients are discharged home when their condition has partially remitted. And as home treatment is so widely available, psychiatric wards have become a destination for those unable to be cared for in community settings. As a result these environments have become more disturbed and even more stigmatised, thereby reducing patients’ willingness to be admitted on a voluntary basis. Both professionals and patients may have changed their attitude to the use of involuntary admission during the study period. Although it is unlikely that these would have been sufficient to explain changes in the detention rate of the magnitude observed, the Mental Health Act might have been used more often when consent to admission was ambiguous since it provides important safeguards for patients.

Finally, this paper does not suggest that bed closures intrinsically are inappropriate. This strategy may well be a reasonable course of action; but the bed mix needs to be examined more closely and the rate of bed closures may need to be considered more carefully. The model we present, if refined and shown to be reliable and valid, predicts one additional involuntary civil admission for every two non-secure inpatient beds that are closed in the preceding year. Whereas the resource released in closing a bed is continuous and recurrent, these may not be so for additional admissions. And if lengths of stay decrease with more intensive management of the available beds, the additional resources might best be directed towards early supported discharge and home treatment. Ultimately this study provides important evidence for the need to anticipate the effects of bed closures. Further studies highlighting the underlying predictors within the model are now required.

What is already known on this topic

In England the overall rate of admission for mental disorders has fallen as alternatives to admission and community services have been further developed

Rates of detention under the Mental Health Act have, however, increased in recent decades in England and some other European countries

What this study adds

Since the 1980s the reduction in mental illness bed provision has been closely associated with an increasing rate of involuntary admission in the NHS

This association was strongest when a time lag of one year was introduced between changes (reduction) in mental illness bed provision and subsequent change (increase) in the annual rate of involuntary admissions

Contributors: All authors conceived and designed the study. PK gathered the data and analysed it with SW, with help from JS. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the data. PK wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors were involved in editing consecutive drafts and interpreting the findings. The final draft was approved by all authors. PK and SW are the guarantors.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years. All authors are applicants for an SDO grant pending review to build on these analyses.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d3736

References

- 1.Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007;370:878-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priebe S, Badesconyi A, Fioritti A, Hansson L, Kilian R, Torres-Gonzales F, et al. Reinstitutionalisation in mental health care: comparison of data on service provision from six European countries. BMJ 2005;330:123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wall S, Hotopf M, Wessely S, Churchill R. Trends in the use of the Mental Health Act: England, 1984-96. BMJ 1999;318:1520-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean C, Phillips J, Gadd E, Joseph M, England S. Comparison of a community based service with a hospital based service for people with acute, severe psychiatric illness. BMJ 1993;307:642-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glover G, Arts G, Babu KS. Crisis resolution/home treatment teams and psychiatric admission rates in England. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig TKJ, Garety P, Power P, Rahaman N, Colbert S, Fornelis-Ambojo M, et al. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. BMJ 2004;329:1067-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson S, Nolan F, Pilling S, Sandor A, Hoult J, McKenzie N, et al. Randomised controlled trial of acute mental health care by a crisis resolution team: the north Islington crisis study. BMJ 2005;331:599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhui K, Stansfeld S, Hull S, Priebe S, Mole F, Feder G. Ethnic variations in pathways to and use of specialist mental health services in the UK. Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:105-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weich S. Availability of inpatient beds for psychiatric admissions in the NHS. BMJ 2008;337:970-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weich S, Griffith L, Commander M, Bradby H, Sashidharan SP, Pemberton S, et al. Experiences of acute mental health care in an ethnically diverse inner city: qualitative interview study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemio l 2010: published online 3 November. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Healthcare Commission. The pathway to recovery: a review of NHS acute inpatient mental health services. Healthcare Commission, 2008.

- 12.Rethink. Future perfect? Outlining an alternative to the pain of psychiatric in-patient care. Rethink, 2005.

- 13.Davidge M, Elias S, Jayes B, Wood K, Yates J. Survey of English mental illness hospitals. Health Service Management Centre, 1993.

- 14.Bindman J, Tighe J, Thornicroft G, Leese M. Poverty, poor services, and compulsory psychiatric admission in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2002;37:341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Information Centre. Inpatients formally detained in hospitals under the Mental Health Act 1983 and other legislation. Government Statistical Service, 2009.

- 16.Department of Health. Bed availability and occupancy. DH, 2009.

- 17.Velleman P. Definition and comparison of robust nonlinear data smoothing algorithms. J Am Stat Assoc 1980;75:609-15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health. In-patients formally detained in hospital under the Mental Health Act 1983 and other legislation, England: 1991-92 to 1996-97. DH, 1988.

- 19.Keown P, Mercer G, Scott J. A retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics, involuntary admissions under the Mental Health Act 1983, and the number of psychiatric beds in England 1996-2006. BMJ 2008;337:1837-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennewith O, Amos T, Lewis G, Katsakou C, Wykes T, Morriss R, et al. Ethnicity and coercion among involuntarily detained psychiatric in-patients. Br J Psychiatry 2010;196:75-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]