Abstract

An ethanolic extract of Artemisia dracunculus L. (PMI-5011) was shown to be hypoglycemic in animal models for Type 2 diabetes and contain at least 6 bioactive compounds responsible for its anti-diabetic properties. To evaluate the bioavailability of the active compounds, high fat dietary induced obese C57BL/6J male mice were gavaged with PMI-5011 at 500 mg/kg body weight, after 4 h of food restriction. Blood plasma samples (200 uL) were obtained after ingestion, and the concentrations of the active compound in the blood sera were measured by electrospray LC-MS and determined to be maximal 4–6 h after gavage. Formulations of the extract with bioenhancers/solubilizers were evaluated in vivo for hypoglycemic activity and their effect on the abundance of active compounds in blood sera. At doses of 50–500 mg/kg/day, the hypoglycemic activity of the extract was enhanced 3–5 fold with the bioenhancer Labrasol, making it comparable to the activity of the anti-diabetic drug metformin. When combined with Labrasol, one of the active compounds, 2′, 4′-dihydroxy-4-methoxydihydrochalcone, was at least as effective as metformin at doses of 200–300 mg/kg/day. Therefore, bioenhancing agents like Labrasol can be used with multi-component botanical therapeutics such as PMI-5011 to increase their efficacy and/or to reduce the effective dose.

1. Introduction

PMI-5011 is a botanical extract prepared from Artemisia dracunculus L. (Russian tarragon), a culinary herb with anti diabetic properties. PMI-5011 treatment decreases blood glucose concentrations in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and genetically diabetic KK.Cg-Ay/+ (KK-Ay) mice but does not effect blood glucose concentrations in non-diabetic mice or rats (Ribnicky et al., 2006). The historical use of the plant, together with recent chronic toxicology studies and AMES testing suggest that the extract is safe (Ribnicky et al., 2004). Biological activities associated with the anti-diabetic effects of PMI-5011 include the stimulation of insulin-mediated glucose uptake into cultured skeletal muscle cells (Cefalu et al., 2008), inhibition of PEPCK (regulator of hepatic glucose output) expression in cultured hepatocytes and in the liver tissue of diabetic animals (Cefalu et al., 2008; Ribnicky et al., 2006) and enhancement of insulin sensitivity via a reduction of phosphastase activities such as PTP1-B (Wang et al., 2006). Therefore, several modes of action may contribute to the anti-diabetic activity of PMI-5011 observed in vivo, suggesting that it contains multiple bioactive compounds.

Extensive bioactivity guided fractionation of PMI-5011 using in vitro assays, led to the isolation of 6 compounds which may contribute to the anti-hyperglycemic activity observed in vivo (Schmidt et al., 2008b). The availability of the functional in vitro assays used for the characterization and standardization of the extract was also essential for.the identification of the active components. Bioactivity observed in vitro, however, does not ensure a corresponding activity in vivo. Obtaining sufficient quantities of pure compounds from botanical mixtures for in vivo testing, however, can be difficult especially when the putative bioactives are present at low concentrations, thus complicating in vivo validation of bioactivity (Ribnicky et al., 2008). However, analysis of the active compounds in the blood plasma of treated animals helps to establish a correlation between the in vitro and in vivo activities. In addition, the relationship between plasma concentrations of active compounds and their associated bioactivity can be used to evaluate bioavailability.

Many bioactive compounds from plants, including compounds contained in food, are poorly bioavailable because of weak absorption and/or rapid elimination (Scalbert and Williamson, 2000). For example, the anthocyanins from blackberry, one of the richest sources of anthocyanins that serve as natural antioxidants, are less than 1% bioavailable in rats (Felgines et al., 2002). In fact, the role of dietary antioxidants as defense against free radical damage is currently being questioned since they are found at only micro and nano molar concentrations in vivo (Holst and Williamson, 2008). Polyphenols, including anthocyanins, are a large class of phytochemicals that are the focus of research in many areas of disease prevention and treatment. A number of factors are noted to impact the bioavailability of polyphenols, such as growing conditions of the plants, cooking and processing conditions, the matrix in which they are presented and solubility (Manach et al., 2004). Botanical preparations containing active phytochemicals are similar to food in this respect. The administration of a pure bioactive compound, a compound contained within its original plant matrix, or a concentrated formulation of a compound in a modified matrix, may have distinct effects on the levels of active compounds in the blood.

Poorly water-soluble bioactive compounds are often noted for low bioavailability because of inefficient dissolution, dispersion, absorption and circulatory retention and are often formulated with lipid-based vehicles. The beneficial effects of dietary fats on the bioavailability of hydrophobic drugs has guided the development of lipid-based formulation vehicles (Humberstone and Charman, 1997). A wide range of commercial products that improve solubility and bioavailability of pharmaceuticals and related products is currently available and designed for a variety chemical classes with a wide range of dissolution characteristics. Many bioenhancing agents consist of an oil and a surfactant (or some combinations of each) that, when formulated with a bioactive agent, form an emulsion on contact with water. These combination products are often called self emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) and yield emulsion droplets that range in size, membrane permeability and thermostability. Labrasol is a commercial bioenhancer consisting of a mixture of glyceride esters of polyethylene glycol and fatty acids. Labrasol enhances both membrane permeability and intestinal absorption of cephalexin, a widely used β lactam antibiotic (Koga et al., 2002) and significantly improves the efficacy of Vancomycin, a water soluble glycopeptide antibiotic with poor absorption characteristics (Prasad et al., 2003). In addition to enhancing solubility, permeability and absorption, bioenhancers, such as Labrasol that contain certain types of surfactants, are also know to further improve the bioavailability of absorbed compounds by acting as p-glycoprotein inhibitors and thereby decreasing intestinal efflux (Yu et al., 1999). In this study we develop methods to determine the bioavailability of the active compounds from a complex botanical therapeutic used for diabetes and identify a formulation with improved solubility, bioavailability and bioactivity in a murine model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The seeds of Artemisia dracunculus L. were purchased from Sheffield’s Seed Co., Inc. (Locke, New York). The plants were grown in hydroponics and their shoots harvested when plants were beginning to flower after about 4 months. The harvested plants were frozen and stored at −20°C prior to extraction. The chalcone, 2′, 4′–dihydroxy-4-methoxydihydrochalcone (DMC-2), was produced by custom synthesis by Gateway Biochemical Technology, Inc. to 99% purity. Labrasol, Labrafil M 1944 CS and Capryol 90 were obtained from Gattefosse Corp., Westwood, NJ. Capmul MCM was obtained from ABITEC Corp., Paris Il and cyclodextrin from Sigma, St Louis MO.

2.2. Preparation of extract

To produce PMI-5011, 4 kilograms of the harvested shoots was heated to 80°C, with 12 L of 80% ethanol (v/v) for 2 h. The extraction continued for an additional 10 h at 20°C. The extract was then filtered through cheesecloth and evaporated with a rotary evaporator to 1L. The aqueous extract was freeze dried for 48 h and the dried extract was homogenized with a motor and pestle. PMI-5011C was prepared in a similar fashion using 95% ethanol as the initial extraction solvent.

2.2. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis

Extracts were fractionated and analyzed with the Waters (Milford, MA) LC-MS Integrity™ system consisting of a W616 pump and W600S controller, W717plus auto-sampler, W996 PDA detector and a Varian 1200L (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA) triple quadrupole mass detector with electrospray ionization interface (ESI), operated in either positive, or negative ionization mode. The electrospray voltage was −4.5 kV, heated capillary temperature was 240 ° C, sheath gas air for the negative mode, and electrospray voltage 5 kV and sheath gas nitrogen for the positive ionization mode; mass detector scanning from 110 to 1400 atomic mass units. Data from the Varian 1200L mass detector was collected and compiled using Varian’s MS Workstation, v. 6.41, SP2. Substances were separated on a Phenomenex® Luna C-8 reverse phase column, size 150 × 2 mm, particle size 3 µm, pore size 100 Å, equipped with a Phenomenex® SecurityGuard™ pre-column. The mobile phase consisted of 2 components: Solvent A (0.5% ACS grade acetic acid in double distilled de-ionized water, pH 3–3.5), and Solvent B (100% Acetonitrile). The mobile phase flow was adjusted at 0.25 ml/min with a gradient from 5% B to 95%B over 35 min.

2.3. Formulation of the extract

PMI-5011, PMI-5011C, and metformin were dissolved in 10% DMSO for the initial evaluation of bioactivity. For the study comparing the effect of excipients on bioactivity, PMI-5011 was formulated with 100% DMSO, Labrasol, Labrafil M 1944 CS, Capryol 90, Capmul MCM or 10% cyclodextrin. PMI-5011, PMI-5011C and DMC-2 were formulated with 66% Labrasol for the remaining studies. Compounds or extracts were dissolved into the delivery vehicle at 10 to 100 mg/ml in order to provide a dose to the animals of 50 mg/kg B.W. to 500 mg/ kg B.W. in a gavage volume of 200–250 uL.

2.4. Plasma analysis of the blood from the treated mice

Trunk plasma was prepared from blood that was collected after carbon dioxide inhalation and decapitation of treated animals. The plasma from treated mice (200 uL, stored at −20°C prior to analysis) was mixed with 200 uL phosphate buffer, Ph 5.5, and 500 uL water and 20 uL enzyme solution (glucuronidase/sulfatase β glucuronidase, TypeHP-2, from Helix pomatis 101400 units/mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 15 h for hydrolysis of bound forms (Richelle et al., 2002). The samples were then cooled and diluted with 1 mL water and defatted with 2 mL hexane in a glass screw top test tube and partitioned with 3 × 2mL ethyl acetate. The pooled ethyl acetate partitions were dried by speed vac and resuspended in 125 uL, transferred to an insert lined HPLC sample vial and analyzed as described above.

2.5. Methods for evaluating antidiabetic activity in mice

The experimental protocols were approved by Rutgers University Institutional Care and Use Committee and followed federal, and state laws. Five-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) and were acclimatized for 1 week before being randomly assigned into the experimental groups. The animals were housed four to a cage with free access to water in a room with a 12:12 h light–dark cycle (7:00 am–7:00 pm), a temperature of 24±1 °C and the animals were weighed weekly. During the acclimatization period, each animal was fed a regular Chow diet (Company and diet needed) ad libitum. At 6-weeks old, the mice were randomly divided into two groups; low fat or very high fat fed groups. The mice continued to receive either a low fat diet (LFD; 10%kcal from fat, Diet ID)) or very high-fat diet (VHFD; 60% kcal from fat; diet ID) for a 12-week period. Body weights were measured weekly, and at every other week blood was collected for blood glucose analysis at designated times after a 4 h food restriction using a glucometer. Animals fed with VHFD were food restricted for 4 hours (from 7 A.M. to 11 A.M.) and gavaged with plant extracts (500 mg/kg) or vehicle to test efficacy of plant extracts. Animals fed with LFD were also food restricted for 4 h. Blood glucose readings were made 0, 3, and 6 hours after treatment (animals were fasted during the testing period). As a positive control, metformin was administered instead of plant extract at a dose of 300 mg/kg (MET300).

3. Results

Previous investigations examining the in vivo hypoglycemic activity of Artemisia dracunculus were conducted with extract produced from fresh plants and called PMI-5011 (extract produced with 80% ethanol) (Ribnicky et al., 2006). The in vitro studies that were subsequently used for bioactivity-guided fractionation and isolation of bioactive compounds were also conducted with PMI-5011 (Govorko et al., 2007; Logendra et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006). Since the newly identified compounds were relatively non-polar, the extraction efficiency of the identified bioactives could be increased to favor higher concentrations of these compounds in the extract. As predicted, 95% ethanol increased the concentrations of active compounds (approximately 65% average increase, data not shown). Based on the average abundance of the ions measured in the extracts and from a standard curve produced from DMC-2, the concentration of DMC-2 was calculated to be 0.95 mg/g in PMI-5011 and 1.70 mg/g in PMI-5011C. The other compounds were at a similar concentration but could not be more precisely quantified with a standard curve. Surprisingly, however, the more concentrated extract, PMI-5011C, had lower hypoglycemic activity as measured in vivo using insulin resistant C57Bl/6 mice as shown in Fig. 1. We hypothesized that the reduction of the activity was based on the poor solubility of the less polar extract, apparent from its tar-like physical properties.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the hypoglycemic activity of different preparations of Artemisia dracunculus L extracted with either 80% ethanol (PMI-5011) or 95% ethanol (PMI-5011C) and metformin. Blood glucose was measured at different times (0–8 h) following the administration of the extract by gavage.

Since diminished bioavailability of the compounds from PMI-5011C could result in the loss of activity, methods were developed to measure the compounds in the plasma of treated animals. Plasma measurements of the compounds could be used to evaluate both the bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of the active compounds and to relate this bioavialability to the observed pharmacological effect. The chromatographic analysis of bioactives from PMI-5011 are shown in Fig. 2. The plasma was enzymatically hydrolyzed, as previously described, in order to release the compounds from possible bound forms (Richelle et al., 2002). This hydrolysis procedure is commonly used with the plasma analysis of botanical compounds because many active compounds are modified in the plasma for transport, it is often uncertain which form is associated with the activity and because animals and humans may modify the same compound in a different way, such as with the glucuronidation vesus the sulfation of epicatechin from green tea (Vaidyanathan and Walle, 2002). LC-MS-SIM was utilized to selectively measure the masses of the bioactive compounds of interest that were present in greatest abundance (Fig. 2A.). Masses and retention times of the plant and plasma-derived compounds corresponded to those of pure compounds as shown in Fig. 2B–C. The peaks corresponding to each of the compounds from the extract is shown in Fig. 2A. The peaks from the analysis of the compounds in the plasma are shown in Fig. 2D. The ratio of 2′, 4–dihydroxy-4′-methoxydihydrochalcone (DMC-2) and sakuranetin was maintained in the plasma compared to the plant extract while the ratio of davidigenin and 6-demethoxycapillarison was reversed, however, any differences in the relative adundance of the compounds would be the result of differences in absorption or metabolism. Additional active chalcone that was previously identified (2′, 4′–dihydroxy-4-methoxydihydrochalcone) (Wang et al., 2006) was detected in some of the analyses (data not shown) but was not a focus in this study because it was present in lower concentrations, and likely to be less active.

Fig. 2.

LC-MS analysis of bioactive compounds in the plasma of C57 mice gavaged with PMI-5011 at 500 mg/kg BW using selected ion monitoring (SIM) for the identification of specific compounds. Panel A SIM chromatogram for PMI-5011, Panel B SIM chromatogram for standards of 6-demethoxycapillarisin and davidigenin, Panel C SIM chromatogram for standards of sakuranetin and 2′,4′-dihydroxy-4-methoxydihydrochalcone (DMC-2), Panel D SIM chromatogram for plasma from animals treated with PMI-5011.

To improve the bioavailability of the bioactives from PMI-5011, commercially available products with a range of solubility/bioenhancing characteristics were then formulated with PMI-5011 and evaluated for hypoglycemic activity in the same acute animal model utilizing the C57 BL/6J mice (Fig. 3). While not all excipients were able to completely dissolve the extract into a clear solution, each of the animals received the same amount of extract as either a solution or suspension. Labrasol was able to dissolve the extract completely and was associated with the greatest bioactivity (Fig. 3). Based on its high hydrophilic-lipophilic balance value and previously reported studies, Labrasol was the most effective excipient tested (Kommuru et al., 2001).

Fig. 3.

The effect of PMI-5011 (500 mg/kg) in combination with different bioenhancers/solubilizers on blood glucose concentrations of C57B mice. Blood glucose was measured at different times (0, 2 and 4 h) following the administration of the extract by gavage. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Since Labrasol is miscible with water, polar compounds can also be solubilized/emulsified with it, including metformin. Metformin was used in all experiments as a positive control and is insoluble in 100% Labrasol. When the Labrasol concentration was decreased below 66%, however, the activity of PMI-5011 was decreased as well (Fig. 4.). The 66% Labrasol vehicle did not have any hypoglycemic effects without the extract (Fig 4) nor did 100% Labrasol (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

The effect of Labrasol concentration as a delivery formulation on the hypoglycemic activity of PMI-5011 (500 mg/kg). Blood glucose was measured at 0, 3 and 6 h following the administration of the extract by gavage. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

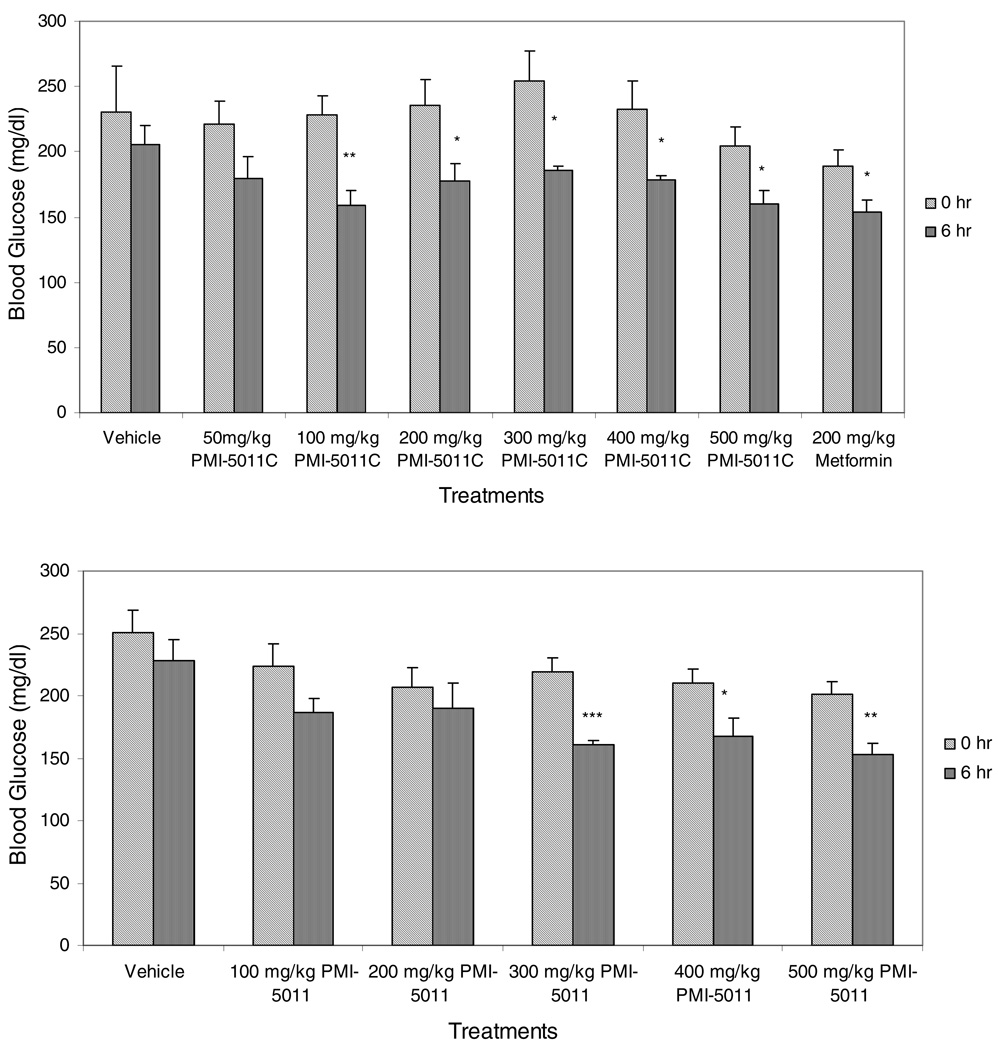

Both PMI-5011 and PMI-5011C were retested for their hypoglycemic activity over a range of doses using 66% Labrasol as the gavage vehicle (Fig. 5). PMI-5011 was significantly active in the acute assay over the dose range of 300mg/kg to 500 mg/kg. The more concentrated PMI-5011C was significantly active at lower doses as low as 100 mg/kg. At the dose of 200 mg/kg, PMI-5011C appears to have greater hypoglycemic activity than metformin at the same dose.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the hypoglycemic activity of extracts of Artemisia dracunculus that were extracted with either 80% ethanol (PMI-5011) or 95% ethanol (PMI-5011C) and formulated with 66% Labrasol. Blood glucose was measured at 0 and 6 h following the administration of the extract by gavage. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

The 5 components of the extract associated with the hypoglycemic activity were measured after the plasma was treated with an enzyme digestion to release the compounds from bound forms present in the plasma. Analysis of the plasma from the treated mice showed that all of the active compounds were detected 1 h after gavage (Fig. 6.). The data are provided as abundance which is the sum of the free and bound forms of compounds in plasma. Since chemical standards of each were not available, precise conversion of abundance to concentration was not performed for each of the compounds, although abundance and concentration are directly related. At 4 h after treatment, the plasma concentration for DMC-2 was calculated to be 1.73 µg/ml for the mice treated with DMC-2 and was 20 times lower in the mice treated with the extract. The abundances for the other compounds shown in Fig.6 correspond to low picomolar concentrations.

Figure 6.

Relative abundance of the active compounds of PMI-5011 as measured by LC-MS in the blood plasma of C57 mice treated with Pure DMC-2 (2′, 4′–dihydroxy-4-methoxydihydrochalcone) formulated with 66% Labrasol or PMI-501l formulated with 66% Labrasol over a 6 h period. DMC-2, Demethcap (6-demethoxycapillarison), DMC-1 (2′, 4–dihydroxy-4′-methoxydihydrochalcone) and sakuranetin are components of PMI-5011.

The abundance of the compounds in the plasma peaked between 4 and 6 h following treatment by gavage. A longer time course was not performed because the animals were food restricted during the treatment period and because the concentrations were declining. The abundance of the DMC-2 in the plasma of mice treated with the pure compound was 10–20 fold higher than in the plasma of the mice treated with the extract even at 1 h after gavage (Fig.6.) The pure DMC-2 had equal or greater hypoglycemic activity as metformin when administered at 300 mg/kg with 66% Labrasol to the C57/Bl6J mice and was significantly active at a dose as low 50 mg/kg (Fig. 7.).

Fig. 7.

Hypoglycemic activity of 2′, 4′–dihydroxy-4-methoxydihydrochalcone (DMC-2) over a range of concentrations compared to metformin in C57 Bl/6J mice after 6 h treatment by gavage with 66% Labrasol vehicle. Blood glucose was measured at 0 and 6 h following the administration of the extract by gavage. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Discussion

Hypoglycemic activity of Artemisia dracunculus was previously documented in two different animal models of diabetes but only in instances where the mice were treated by gavage for 7 days as shorter treatment periods were not effective (Ribnicky et al., 2006). In contrast, a single treatment of 5011 when formulated in labrasol led to a significant decrease in circulating glucose concentrations. The bioactivity guided fractionation of the extract, using in vitro assays related to diabetes, lead to the identification of 6 active compounds that may contribute to the hypoglycemic activity observed in vivo (Schmidt et al., 2008a). The identification of these compounds and their activities reinforce the multicomponent and multimechanistic advantage that botanical preparations may provide over single chemical entities (Raskin et al., 2002). Their potential role as active compounds in vivo, however, is only indirectly supported by in vitro results and can only be validated with in vivo studies using the combinations of purified compounds. Since obtaining sufficient quantities of each of the purified compounds for in vivo testing is challenging, correlating their relative concentrations within the extract to in vivo activity may support their role in the observed pharmacological effect. Attempts to create a more concentrated and more active extract, were not successful as demonstrated in Fig. 1. While the lower activity observed with PMI-5011C compared to PMI-5011 could be due to the loss of an active compound that was not yet identified, the reduction in solubility/bioavailability seemed a more logical explanation, based on visual observations.

The evaluation of select solubilizing/bioenhancing agents showed that formulation significantly impacted the bioactivity of PMI-5011 (Fig. 3.). Labrasol promoted the greatest hypoglycemic activity of the agents tested. Labrasol is the commercial name for caprylocaproyl macrogol-8 glyceride produced by Gattefosse Corporation by alcoholysis/esterification reaction of triglycerides from coconut oil and PEG400. It is a well defined mixture of glyceride esters of polyethylene glycol with caprylic and capric fatty acids. Labrasol was originally designed to increase the solubility of water-insoluble drugs by emulsification but has also been shown to enhance oral bioavailability of water soluble drugs and amphiphilic drugs (Koga et al., 2006).

Formulation with Labrasol (66% with water) also increased the bioactivity of concentrated extract, PMI-5011C, relative to the less concentrated version, PMI-5011. Water was used with the Labrasol because metformin, used as a positive control, was not soluble in 100% Labrasol. The extract of Artemisia dracunculus produced with the more polar extraction solvent, PMI-5011, was also not completely soluble in 100% Labrasol. Therefore, a preparation containing 66% Labrasol worked best with all preparations used in this study. The activity of the concentrated extract, PMI-5011C, was tested over a range of doses and found to be effective even at the 50–100 mg/kg range (Fig. 3.). The relative content of the compounds believed to be active by in vitro testing, therefore, do correlate with in vivo activity. The decrease in activity observed during attempts to make the extract more potent were the result of decreased solubility and bioavailability.

The chalcone, DMC-2, was identified as active in vitro with activity guided fractionation based on three independent bioassays and was also the most abundant of the active compounds identified (Schmidt et al., 2008a). DMC-2 was available in sufficient quantity for in vivo testing because it was chemically synthesized (Logendra et al., 2006). As a pure compound formulated with 66% Labrasol, the DMC-2 had comparable activity to metformin at the dose of 300 mg/kg and was significantly active at doses as low as 50 mg/kg (Fig. 7.). The activity of metformin did decrease significantly at doses lower than 300 mg/kg as shown by Fig. 5, where a metformin dose of 200 mg/kg was less active than the extract at that dose and less active than DMC-2 at a dose of 150 mg/kg (Fig. 7.). The other compounds identified in vitro were not validated in vivo.

PMI-5011C was active at similar doses to pure DMC-2 while the plasma concentrations of DMC-2 were 10–20 times lower in the animals treated with the extract compared to the animals treated with DMC-2. The discrepancy between the actual dosage (pure compound versus extract with small amounts of actives) and plasma abundance that results, confirms the earlier hypothesis that at least 5 other components in the extract contribute to the overall hypoglycemic activity of the extract.

The data from this study demonstrates the utility of bioenhancing agents such as Labrasol in the formulation of multicomponent botanical preparations such as PMI-5011. The practical use of such formulating agents relies on knowledge of the components that contribute to the in vivo bioactivity of the preparation and methods to relate their blood plasma concentration to a biological activity. Even though the true potential of botanical preparations may rely on the synergistic effects of multiple compounds with distinct activities and unique chemical characteristics, broad spectrum bioenhancing agents that consist of a variety of fatty acid esters and other well defined ingredients can significantly improve their bioavailability. The use of Labrasol with PMI-5011/PMI-5011C increased the activity of the botanical preparation from mildly antidiabetic to a dosage form with drug-like activity comparable to metformin. The use of appropriate formulations can also provide drugs or botanicals with biological activity that might not otherwise occur, which is an important research consideration. The precise mechanism by which bioenhancers act remains to be elucidated for each bioactive compound, however, since they have a variety of influences on absorption, secretion, transport and metabolism.

Acknowledgments

Support: Research supported by the NIH Center for Dietary Supplements Research on Botanicals and Metabolic Syndrome, grant # 1-P50 AT002776-01; Fogarty International Center of the NIH under U01 TW006674 for the International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups; Rutgers University and Phytomedics Inc. (Jamesburg NJ, USA);

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Cefalu WT, Ye J, Zuberi A, Ribnicky DM, Raskin I, Liu Z, Wang ZQ, Brantley PJ, Howard L, Lefevre M. Botanicals and metabolic syndrome. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87:481. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.2.481S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felgines C, Texier O, Besson C, Fraisse D, Lamaison JL, Remesy C. Blackberry anthocyanins are slightly bioavailable in rats. J Nutr. 2002;132:1249. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.6.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govorko D, Logendra S, Wang Y, Esposito D, Komarnytsky S, Ribnicky DM, Poulev A, Wang ZQ, Cefalu WT, Raskin I. Polyphenolic Compounds from Artemisia dracunculus L. Inhibit PEPCK Gene Expression and Gluconeogenesis in an H4IIE Hepatoma Cell Line. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00420.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst B, Williamson G. Nutrients and phytochemicals: from bioavailability to bioefficacy beyond antioxidants. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:73. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humberstone AJ, Charman WN. Lipid based vehicles for the oral delivery of poorly water soluble drugs. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1997;25:103. [Google Scholar]

- Koga K, Kawashima S, Murakami M. In vitro and in situ evidence for the contribution of Labrasol and Gelucire 44/14 on transport of cephalexin and cefoperazone by rat intestine. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2002;54:311. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(02)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga K, Kusawake Y, Ito Y, Sugioka N, Shibata N, Takada K. Enhancing mechanism of Labrasol on intestinal membrane permeability of the hydrophilic drug gentamicin sulfate. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2006;64:82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kommuru TR, Gurley B, Khan MA, Reddy IK. Self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) of coenzyme Q10: formulation development and bioavailability assessment. Int J Pharm. 2001;212:233. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00614-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logendra S, Ribnicky DM, Yang H, Poulev A, Ma J, Kennelly EJ, Raskin I. Bioassay-guided isolation of aldose reductase inhibitors from Artemisia dracunculus. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1539. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Remesy C, Jimenez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:727. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad YV, Puthli SP, Eaimtrakarn S, Ishida M, Yoshikawa Y, Shibata N, Takada K. Enhanced intestinal absorption of vancomycin with Labrasol and D-alpha-tocopheryl PEG 1000 succinate in rats. Int J Pharm. 2003;250:181. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00544-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin I, Ribnicky DM, Komarnytsky S, Ilic N, Poulev A, Borisjuk N, Brinker A, Moreno DA, Ripoll C, Yakoby N, O'Neal JM, Cornwell T, Pastor I, Fridlender B. Plants and human health in the twenty-first century. Trends in Biotechnology. 2002;20:522. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)02080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribnicky DM, Poulev A, O'Neal J, Wnorowski G, Malek DE, Jager R, Raskin I. Toxicological evaluation of the ethanolic extract of Artemisia dracunculus L. for use as a dietary supplement and in functional foods. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004;42:585. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribnicky DM, Poulev A, Schmidt B, Cefalu WT, Raskin I. Evaluation of botanicals for improving human health. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87:472S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.2.472S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribnicky DM, Poulev A, Watford M, Cefalu WT, Raskin I. Antihyperglycemic activity of Tarralin, an ethanolic extract of Artemisia dracunculus L. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:550. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richelle M, Pridmore-Merten S, Bodenstab S, Enslen M, Offord EA. Hydrolysis of isoflavone glycosides to aglycones by beta-glycosidase does not alter plasma and urine isoflavone pharmacokinetics in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2002;132:2587. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.9.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalbert A, Williamson G. Dietary intake and bioavailability of polyphenols. J Nutr. 2000;130:2073S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.8.2073S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt B, Ribnicky DM, Poulev A, Logendra S, Cefalu WT, Raskin I. A Natural History of Botanical Therapeutics. Metabolism. 2008a doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt BM, Ribnicky DM, Poulev A, Logendra S, Cefalu WT, Raskin I. A Natural History of Botanical Therapeutics, Metabolism. Clinical and Experimental in press. 2008b doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan JB, Walle T. Glucuronidation and sulfation of the tea flavonoid (−)-epicatechin by the human and rat enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:897. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.8.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Ribnicky DM, Logendra S, Poulev A, Ma J, Yang H, Kennelly E, Liu X, Raskin I, Cefalu WT. 66th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association. Washington D.C.: 2006. Jun 9–13, Bioactives from an extract of Artemisia dracunculus L. exhibit potent inhibitory activities for PTB1B in human skeletal muscle culture. [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Bridgers A, Polli J, Vickers A, Long S, Roy A, Winnike R, Coffin M. Vitamin E-TPGS increases absorption flux of an HIV protease inhibitor by enhancing its solubility and permeability. Pharm Res. 1999;16:1812. doi: 10.1023/a:1018939006780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]