Abstract

Introduction

HIV incidence is the rate of new infections in a population over time. HIV incidence is a critical indicator needed to assess the status and trends of the HIV epidemic in populations and guide and assess the impact of prevention interventions.

Methods

Several methods exist for estimating population-level HIV incidence: direct observation of HIV incidence through longitudinal follow-up of persons at risk for new HIV infection, indirect measurement of HIV incidence using data on HIV prevalence and mortality in a population, and direct measurement of HIV incidence through use of tests for recent infection (TRIs) that can differentiate “recent” from “non-recent” infections based on biomarkers in cross-sectional specimens. Given the limitations in measuring directly observed incidence and the assumptions needed for indirect measurements of incidence, there is an increasing demand for TRIs for HIV incidence surveillance and program monitoring and evaluation purposes.

Results

Over ten years since the introduction of the first TRI, a number of low-, middle-, and high-income countries have integrated this method into their HIV surveillance systems to monitor HIV incidence in the population. However, the accuracy of these assays for measuring HIV incidence has been unsatisfactory to date, mainly due to misclassification of chronic infections as recent infection on the assay. To improve the accuracy of TRIs for measuring incidence, countries are recommended to apply case-based adjustments, formula-based adjustments using local correction factors, or laboratory-based adjustment to minimize error related to assay misclassification. Multiple tests may be used in a recent infection testing algorithm (RITA) to obtain more accurate HIV incidence estimates.

Conclusion

There continues to be a high demand for improved TRIs and RITAs to monitor HIV incidence, determine prevention priorities, and assess impact of interventions. Current TRIs have noted limitations, but with appropriate adjustments, interpreted in parallel with other epidemiologic data, may still provide useful information on new infections in a population. New TRIs and RITAs with improved accuracy and performance are needed and development of these tools should be supported.

Introduction

At a population-level, HIV incidence or the rate of new infections is the most important quantity to measure to assess the current state of the HIV epidemic. Determining where HIV transmission is currently occurring provides important information on particular population sub-groups and geographic areas at highest risk that prevention interventions should target. Temporal trends in HIV incidence can be used to assess the effectiveness of these interventions and monitor changes in transmission patterns.

There are three main approaches to determine HIV incidence in populations: direct measurement in cohort studies, inference from prevalence measurements, or estimation using tests for recent infection (TRI) in cross-sectional surveys; multiple tests may be used in a recent infection testing algorithm (RITA).

In cohort studies, persons are tested for HIV infection in a baseline survey, the HIV-uninfected persons are then followed over time, and re-tested during the follow-up period to determine the observed incidence rate in the cohort. HIV incidence estimated from cohort studies have historically been considered the gold-standard estimate for HIV incidence; however, since HIV infection is a relatively rare event, large sample sizes (up to thousands) and long follow-up periods (>2 years) are required, which presents logistical difficulties and is not sustainable even in resource-rich settings. Estimates of directly observed incidence are prone to biases due to the sampling frame of the cohort under observation [1], differential loss to follow-up among those at most risk of infection, or by the process of repeated testing and counseling in the cohort population leading to changes in behavior [2, 3] and potentially lower observed HIV incidence than in the broader population of interest. Furthermore, the observed HIV incidence estimates only directly relate to the community studied. For example, a rural cohort cannot be used to estimate national incidence or incidence in urban areas.

Because HIV incidence is a component of HIV prevalence, it is possible to estimate HIV incidence rates, indirectly, in a population using HIV prevalence data. One approach, used widely in low-income countries, is to fit a mathematical model to HIV prevalence time-series data [4-14]. Another approach is to make a forward projection of incidence rates using information on prevalence in different sub-populations at high risk for infection, types of behavior and corresponding probabilities of HIV transmission [15]. These model-based calculations provide a reasonable way of estimating incidence, particularly in concentrated epidemics, since assumptions about the variation in risk in the population and patterns of transitioning to high-risk behavior can be readily incorporated. A new model for indirect measurement of HIV incidence uses two cross-sectional age distributions of prevalence measured in general population surveys to infer population-level HIV incidence [16-18]. This method has been validated against directly observed incidence from prospective cohort studies and has shown accuracy in the modelled estimates, overall and across sex and age groups. This approach, however, is not without its challenges. The prevalence data needed are derived from national surveys that are logistically challenging to implement, take years to conduct, and are difficult to standardize over time. In addition, the analysis of cross-sectional age distributions is not reliable if individuals' chances of inclusion in surveys vary by age (as it may within certain sub-populations at risk for HIV infection). Furthermore, incidence will be under-estimated if the household surveys tend to under-represent mobile groups [19]. Internal migration, unless explicitly measured and incorporated in the incidence calculation, would tend to bias sub-national estimates of incidence [16].

The third approach for estimating HIV incidence is the use of TRIs, a laboratory-based method that can distinguish recent from long-term infection in blood specimens from HIV-infected persons [20-32]. The advantage of the TRI approach over directly observed incidence and indirect measurements of incidence is that TRIs do not require following participants longitudinally nor collecting serial blood samples, but are applied to blood samples collected at a single point in time. In addition, estimating incidence using data from TRIs does not require assumptions about prevalence and mortality. Though TRIs have been used for the past decade to estimate population-level HIV incidence, they are prone to substantial assay misclassification, limiting its widespread use as a tool to routinely measure HIV incidence in a population.

This paper reviews the current status and limitation of using TRIs for estimating population-level incidence and what is needed in this field to develop, evaluate and implement improved TRIs and incidence estimation methods.

Tests for Recent Infection (TRI)

Researchers have developed TRIs based on the principle that the HIV antibody response matures over time and that specimens from people with recently acquired infection will test below a defined level on these antibody-based TRIs during a defined post-seroconversion “window period” (Figure 1) [20]. These tests can then be used to estimate the number of recently infected persons in a sample of HIV-seropositive persons drawn from a population, and the resulting number is used to estimate HIV incidence. The underlying principles of the various HIV incidence assays, including status of availability, are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Tests for recent HIV infection (TRI) – diagram of the principle of a post-seroconversion window period based on the maturation of the antibody response to HIV infection. Specimens that are reactive on a sensitive assay at the detection limit are then tested on the TRI. Specimens that are non-reactive or negative on the TRI are considered “recent,” reactive or positive specimens are considered long-standing.

Table 1. Tests for recent HIV infection: underlying principles and availability.

| Factor | Detuned (Abbott 3A11 HIVAb) |

Detuned (bioMérieux Vironostika-LS EIA) |

BED (Calypte® HIV- 1 BED Incidence EIA) |

Avidity (Abbott AxSYM HIV 1/2/gO) |

Avidity (Ortho Vitros assay) |

IDE/V3 | Anti p24 IgG3 | Innolia | Particle agglutination assay |

Uni-Gold Recombigen |

rIDR-M avidity index EIA |

rIDR-M limiting antigen avidity EIA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of antibody measured | Anti-HIV quantity | Anti-HIV quantity | Anti-HIV gp41 quantity (as proportion of total IgG) | Anti-HIV quality (antibody avidity) | Anti-HIV quality | Anti-HIV gp41 and V3 quantity | Anti-HIV p24 IgG3 | Presence/absence and quantity of antibody | Anti-HIV quantity | Anti-HIV quantity | Anti-HIV quality (antibody avidity) | Anti-HIV quality (antibody avidity) |

| Primary reference | Janssen et al (24) | Kothe et al. (25) | Parekh et al (27) | Suligoi et al. (28) | Chawla et al (22) | Barin et al (21) | Wilson et al (30) | Schupbach et al (32) | Li et al (26) | Constantine et al (23) | Wei et al 2010 (29) | Wei et al 2010 (29) |

| Commercially available | Yesa (Modified procedure from product insert) | Yesa (Modified procedure from product insert) | Yes | Yes (Modified procedure from product insert) | Yes (modified procedure from kit insert) | No (in-house assay–reagents may be sourced commercially) | No | Yes (modified procedure from kit insert) | Yes Modified commercial assay | Yes Modified commercial assay | Liscensed, will be available | Liscensed, will be available |

| Assay availability | No Longer Available | Limited | World-wide | Europe, some non-European countries | Europe – some non European countries | Reagents generally available – some components may have limited availability | “In house” assay. All reagents available commercially | World-wide | Assay particles widely available-some import restrictions | World-wide but some local import restrictions | Will be available world-wide | Will be available world-wide |

| Assay generation | 1st generation viral lysate from subtype B, spiked with purified gp41. Assay detects IgG (HIV-1 group M) | 1st generation viral lysate from subtype B. Assay detects IgG (HIV-1 group M) | 2nd generation, branched chain peptide from gp41 HIV-1 subtypes B, E and D. Assay detects IgG (HIV-1 group M) | 3rd generation, Mixture of recombinant and peptide antigens. Detects IgG and IgM (HIV-1 groups M, O & HIV-2) | 3rd generation, Mixture of recombinant and peptide antigens. Detects IgG and IgM (HIV-1 groups M, O & HIV-2) | 2nd generation indirect assay | Direct ELISA. Recombinant p24 (HIV-1 group M). Assay detects IgG3. | Not applicable | 1st generation | 3rd generation | 2nd generation multi-type gp41 recombinant proteína HIV-1 group M | 2nd generation multi-type gp41 recombinant proteína HIV-1 group M |

| Special equipment required | Yes | No | No | Yes (AxSYM Analyser) | Yes – vitros analyser | No | No | No (if using automated reading then special reader required) | No | No | No | No |

| Working dilution | 1:20,000 | 1:20,000 | 1:101 | 1:10 | 1:10 | 1:100 | 1:10 | 1:100 | 1:40,000 | 1:115 | 1:100 | 1:100 |

| Reagent storage requirements | 4°C | 4°C | -20°C; 4°C (depending on reagent) | 4°C | 4°C | 4°C/-20°C | -20°C | 4°C | 4°C | 4°C | 4°C/-20°C | 4°C/-20°C |

| Automated | Yes | Partial automation possible | Partial automation possible | Yes | Yes | No | No | No (Partial automation of reading step possible) | No | No | No | No |

| Assay duration | 90 minutes | 90 minutes per plate | 245 minutes per plate | Minimum of 60 minutes; 2-3 minutes for each additional specimen above 10 | Minimum of 60 minutes; 2-3 minutes for each additional specimen above 10 | 2 hours | 350 minutes | 18 hours including 16 hours overnight incubation | 6-24 hours | 10 minutes | 2-3 hours | 2-3 hours |

| Specimens per run | 48 in screening mode 16 in confirmatory mode | 84 in screening mode 28 in confirmatory mode | 85 in screening mode 28 in confirmatory mode | Minimum of 1. Can be continually loaded on to the machine | Minimum of 1. Can be continually loaded on to the machine | 44 specimens per run | 80 specimens per microplate | Minimum of one | Approx 90 per plate | 1 per test device | 42 (two-well) | 84 (one-well) |

| Confirmatory algorithm utilized to confirm initial results | Yes Triplicate retests, each from individual dilutions | Yes Triplicate retests, each from individual dilutions | Yes Triplicate retests, each from individual dilutions | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes Triplicate retestes, each from individual dilutions | Yes Triplicate retestes, each from individual dilutions |

| Mean window period (WP) estimated | Yes (For some subtypes) | Yes (For some subtypes) | Yes | No | Yes - 142 | No – estimated to be 6 months, some work suggests shorter WP | Yes (For subtype B) | No – sensitivity/specificity on determining recent infection within 12 months | 190 days | No - assay calibrated against detuned to give WP of 133 days | Under development | Under developement |

| WP variations by subtype | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Under development | Under developement |

| Percent of AIDS cases misclassified as recent HIV infection | 5% | 2.4% | 2-3% | Unknown | % unpublished but decline in reactivity noted | Yes (9%) | Unknown | Unknown | 4% | Unknown | Under development | Under developement |

| Assay specificity affected by antiretroviral therapy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Under development | Under developement |

No longer commercially available

Over a decade ago, scientists at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and collaborators reported on the use of the first such antibody-based assay in a method known as the serologic testing algorithm for recent seroconversion (STARHS) [24]. This algorithm employed a sensitive commercial HIV-1 enzyme immunoassay (3A11, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois)) and a less-sensitive (LS or “detuned”) version of this assay; the specimen from a recently infected person was reactive on the sensitive assay, but non-reactive on the LS assay. A similar approach was used with another commercial HIV-1 assay (Vironstika, BioMerieux Inc., Durham, NC)[25, 31]. However, it was subsequently found that these assays (both based on HIV-1 subtype B, most common in the United States and Europe) had significantly different window periods for non-B subtypes, which predominate in other regions of the world [33-35]. Consequently, without accounting for HIV-1 subtype distributions in the sample, use of these assays would yield inaccurate estimates of HIV incidence. An additional practical problem was that both of these commercial assays that formed the basis for the algorithm were removed from the market by their manufacturers, as they became outdated.

Subsequently, other immune-response-maturation approaches to identifying recent HIV-1 infection were developed, most notably the “BED capture enzyme immunoassay” (i.e. the BED assay) that was commercialized in 2002 [27]. To date, the BED assay has become the most widely used TRI in the world. It is currently used in the U.S. to estimate new HIV infection in the CDC national HIV/AIDS case reporting system [36] and in some middle- to low-income countries for the purposes of HIV incidence surveillance in settings such as antenatal clinic surveillance, most-at-risk-population surveillance, and general population-based surveys with HIV testing [36-43].

All TRIs are challenged by the diversity of the evolving individual immune responses among HIV-infected individuals. The performance of the assays is affected by several factors, including the predominant HIV subtype in the survey setting and low anti-HIV antibody titers found in late stage HIV infection, persons on antiretroviral therapy (ART), among long-term non-progressors / “elite controllers” [20] and among some persons not in these categories for reasons that are not well understood. These factors can lead to substantial misclassification at the individual level, and for that reason, the currently existing TRIs should not be used for individual diagnosis of recent HIV infection. The key application for TRIs is to monitor the HIV epidemic in populations and measure the impact of HIV prevention programs at the community and country level. However, population-level incidence can be substantially impacted by misclassification, producing overestimates of true population-level incidence [38, 44-47]. To minimize this error, the use of case-based adjustments using individual level data that measures or infers duration of infection, formula-based adjustments or application of additional laboratory methods to correct for misclassification of long-term infections as recent infections on the assays may be required [45, 46, 48-54]. Application of these adjustments [39, 42, 45, 46, 55] and analysis of TRI data with other sources of data, such as behavioral and other biologic markers to confirm HIV incidence trends [43, 56] have supported the careful and qualified use of incidence data from TRI in HIV surveillance settings in spite of the limitations.

Estimation of Assay-based HIV Incidence: Mathematical Challenges

When estimating assay-based HIV incidence, one must consider the following theoretical framework to understand the challenges and complexities inherent in estimation of HIV incidence from TRIs. While all TRIs produce ‘recent’ and ‘non-recent’ test results, an ideal TRI is one that obeys the requirement that all HIV-infected persons eventually, and then in perpetuity, produce a ‘non-recent’ result after some time post-infection [57]. Substantial inter-subject variability in how long this takes to happen is acceptable for the purposes of incidence inference provided that the average time it takes individuals to progress is known. A useful mean window period is not so short that very few individuals can be found in the ‘recently infected’ state at any point in time, as this reduces statistical power. Straightforward epidemiological and statistical models deduce a simple incidence ‘estimator’ which expresses the inferred incidence (I) as a function of a survey proportion of ‘recently infected’ individuals (R), uninfected individuals (U), and the mean window period (W): I = R/(UW).

In characterizing a TRI in the context of estimating incidence, one needs to estimate the mean window period and the extent to which the test obeys the ideal condition. Deviation from this ideal is essentially due to two factors: For currently available TRIs, there appear to be subpopulations of HIV-infected persons who fail ever to develop the ‘non-recent’ biomarker. Additionally, there appears to be HIV-infected persons who ‘regress’ to the ‘recent’ biomarker some time after having initially developed the ‘non recent’ biomarker, typically as a result of severe immunosuppression or the effects of ART. This effect can be summarized by attributing a ‘false-recent rate’ to the test among persons with at least one year of HIV infection. The ideal assay has a zero false-recent rate, and in the worst case there is a finite false-recent rate which varies across numerous population strata.

Heuristic post-hoc adjustment factors have been developed to correct misclassification of long-term infection as recent infection on the BED assay by applying an expected false-recent rate to the mathematical formula for calculating HIV incidence [45, 46, 48, 49]. Consistent estimators can be constructed if the false-recent rate is assumed to be known and constant in a given population. Once these values are determined for a given population, the false-recent rate can be incorporated into the mathematical formula used to for calculating incidence, resulting in a significant improvement in the estimated incidence. The inherent uncertainty in estimating the false-recent rate, as well as the way it is used in an unbiased estimator, lead to considerable loss of statistical power and exposure to bias, as compared to the idealized case of a zero false-recent rate [58]. The key challenge facing the development of new TRIs that will improve the accuracy of cross-sectional incidence estimates, is to identify and consistently track one or several biomarkers to obtain a reasonably long mean window period (preferably at least six months) and a very low false-recent rate (preferably below 2%). The latter presents the greatest challenge to date, as current TRIs have documented false-recent rates, based on substantial sample sizes, from as low as 2% to as high as 15% in various populations of HIV-infected persons who had been infected for at least one year [43, 45, 46, 58-63].

Use of Recent Infection Testing Algorithms (RITAs) to Improve Accuracy of HIV Incidence Estimates

A possible solution to improve the accuracy of HIV incidence assays to detect recent infection and estimate population-level HIV incidence is the use of multiple tests in a recent infection testing algorithm (RITA). The use of additional biomarkers associated with the chronic stage of HIV infection could improve specificity. CD4+ cell count in HIV-positive persons is one such biomarker. Individuals who are severely immune compromised may have low levels of anti-HIV antibodies and may produce a ‘recent’ result on a TRI [64, 65]. CD4+ testing has become more widely available in developing countries due to their utility in identifying individuals who need ART and for monitoring treatment [66]. Consequently, CD4+ tests can be a functional component of HIV incidence surveillance [67]. However, there are logistical challenges that may prevent widespread application of CD4+ testing in surveillance systems in resource-constrained settings: CD4+ tests do require the samples to be tested shortly after blood collection (within 1-2 weeks), cannot be performed on stored samples, and cannot be performed on dried blood spots which are collected in many surveillance settings.

Additional indicators of chronic infection include the lack of detectable HIV RNA and the presence of ART in a sample. Samples from subjects with low viral levels, either naturally suppressed or suppressed by ART, tend to have low anti-HIV antibody levels [68, 69]. Since individuals with low viral levels have a survival advantage they will form an increasing proportion of HIV-infected persons in a population as time progresses within an epidemic. Large-scale ART programs rapidly increase the proportion of HIV-infected individuals with low viral levels in a population. With appropriate infrastructure and resources, stored samples can be tested for the presence of HIV RNA and for the presence of drugs used in ART. The exclusion of samples from individuals on ART and with undetectable viral levels from the incidence analysis will substantially increase the accuracy of TRIs when used in cross-sectional surveys [61, 64].

The combination of multiple HIV incidence assays, particularly those that measure different characteristics of the antibody response (e.g. antibody titer and avidity or the strength of the bonding of the antibody to antigen) that evolve over time [20, 61] can also be used to increase specificity and predictive value for detecting recent infection. However, such multi-test algorithms have not yet been rigorously evaluated. Many functional properties of using a combination of assays, such as the window period for both assays in conjunction, are still unknown, but needed for calculation of population-level incidence estimates.

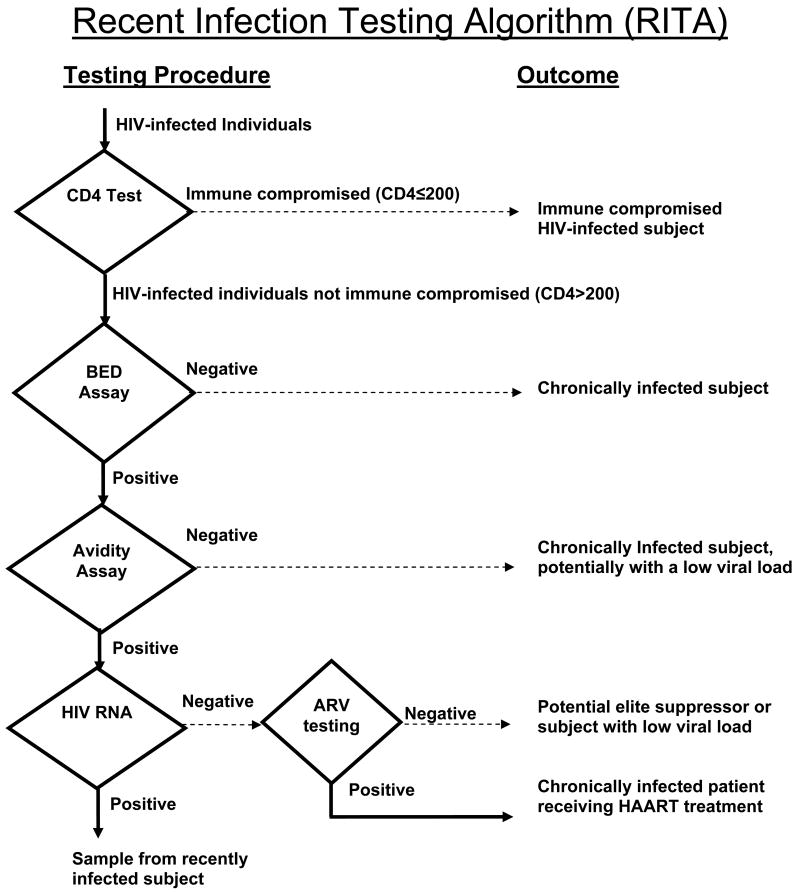

It is possible to include all of these parameters in a RITA for HIV incidence determination by more accurately identifying recently infected persons (Figure 2). First, all persons with a low CD4+ cell count (e.g., <200 or <100 cells/μL) would be excluded. Then a well-characterized assay such as the BED assay could be used as an initial screening tool to identify samples from potentially recently infected individuals. These would then be confirmed by a more specific assay which uses a different biologic principle than the initial assay (e.g. an avidity assay). HIV RNA could then be performed on all samples that initially appear recently infected; specimens with undetectable RNA would be excluded. Ideally, the presence of ART should be determined for specimens found to be recent. The impact of each of these components of on the overall effectiveness of the algorithm is currently being evaluated. It also will be important to assess the cost and logistical feasibility of such an algorithm.

Figure 2.

A recent infection testing algorithm (RITA) for HIV.

Discussion

There is a pressing need to be able to accurately measure HIV incidence in populations in order to assess the status of the epidemic. Moreover, it is critically important to be able to measure the effectiveness of ongoing HIV prevention programs, to better guide future prevention efforts. The United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS), in 2001, set a goal to reduce the number of HIV-infected youth (aged 15-24 years) by 25% in most-affected countries by 2005 [70]. Temporal trends in HIV prevalence among youth aged 15-24 years have been used as a proxy measure for trends in HIV incidence in the general population [71]. Since 2001, considerable efforts have been made in measuring this required U.N. indicator, but very few countries are currently reporting it. Alternative measures of HIV incidence are therefore needed, but as demonstrated are not without major biases.

Most resource-constrained countries rely on mathematical models to infer population-level incidence from cross-sectional surveys of HIV prevalence [6, 14]. The approach proposed by Hallett and colleagues [16, 18, 72] is promising, although it requires inputting HIV prevalence data from at least two national population-based surveys with HIV testing (e.g. Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), AIDS Indicator Surveys (AIS), or similar type of surveys [73]) and assumptions on survival of HIV-infected persons, effect of ART on survival, and in- and out- migration patterns, to model national incidence estimates. Since 2000 there have been at least 25 countries in sub-Saharan Africa that have incorporated HIV testing into population-based surveys [74]. Though only a handful of countries have conducted two surveys of this kind (at the time of writing - South Africa, Zambia, Botswana, Tanzania, and Kenya, Mali, Niger, the Dominican Republic), many countries are in the process of planning for or conducting their second survey and would be eligible to apply this approach as part of a national incidence analysis, granted that appropriate sample sizes for incidence analysis are available. As with all models, there are fundamental assumptions required to produce reliable estimates, including assumptions on stable, low incidence in the population, accurate accounting for international migration, accurate HIV prevalence data, and valid mortality. Violation of any of these assumptions, even to a small degree, would, to a greater or lesser extent, reduce the accuracy of the incidence estimates. Countries should also note that this model is limited to age-specific and gender-specific incidence estimates; further stratification in sub-populations of interest is therefore not possible. As more countries acquire high quality data from national population-based surveys with HIV testing and the accuracy for mortality rate data can be guaranteed, this method should work well as an indirect method for producing national estimates of incidence in a country.

More than a decade after the first antibody-based TRI was introduced, there continues to be high demand from countries for an accurate incidence assay to directly measure recent infection and monitor trends in incidence in cross-sectional surveys. Since 2004, at least 15 countries have used the BED assay for HIV incidence surveillance by applying the assay to HIV-positive specimens from sentinel surveillance, national population-based surveys, or HIV case-surveillance systems [36-43]. While the BED assay has been found to perform reasonable well in longitudinal cohorts following only HIV-uninfected persons over time to the end-point of seroconversion [27, 45], evidence from application of the assay in cross-sectional settings has shown that the assay consistently over-estimates true population-level incidence due to misclassification of a proportion of long-term infection as recent on the assay [38, 44-47]. To account for this countries are advised to correct their assay-based incidence estimates for misclassification based on expected false-recent rates among known chronic infections (infection greater than one year) in a given population [45, 46, 48-53]. In addition, the large sample sizes that are required for reliable TRI incidence estimation probably make it unfeasible to power surveys for sub-national comparisons unless there are large differences among the regions being compared [55, 57]. For optimal performance, quantification of false-recent rates should be locally derived to address expected site and HIV-1 subtype variability in the false-recent rate. Further, surveys should be powered appropriately for monitoring HIV incidence in the general population.

It is evident that ART use, low viral levels, and low CD4+ cell counts in chronically infected persons are associated with error in the incidence estimates from TRIs, due to low levels of antibody response from low viral levels and compromised immune systems, leading to a very high proportion of false-recent classifications [62, 63]. The error associated with these variables does not appear to be constant but varies widely by time and population [58] and will be exacerbated by the (differential) scale-up of ART programs. Surveillance scientists are therefore advised to use timely local measurements of misclassification, and additionally, identify persons on ART, with low HIV RNA levels and with low CD4+ cell counts in surveillance settings and exclude them from the incidence analysis. It is recognized that this requirement poses challenges to surveillance systems that do not currently have the ability to collect information on ART use, viral levels, and CD4+ cell counts directly from respondents and may at best be only indirectly assessed by the survey team. Additionally, collecting data on ART use would require disclosure of persons' HIV-positive status which may be problematic and pose ethical challenges for surveillance officials. A more desirable alternative is post-hoc testing for the presence of ART, CD4 cell count, and viral levels in BED-positive specimens to identify cases to be excluded based on these findings. This option is feasible in settings with appropriate laboratory support and resources for testing.

While the limitations of the current TRIs have hindered expanded implementation of incidence surveillance in most countries, several positive applications of this technology in the past 5 years have been reported. These included critical capacity-building exercises through regional and in-country trainings for laboratory and surveillance personnel [74], successful use of BED adjustment factors to obtain plausible estimates of population-level incidence in some countries [38, 39], triangulation of BED incidence data with behavioural and clinical outcomes to cooroborate observed incidence trends [43, 56] and use of the BED assay with exclusionary conditions such as ART use, low CD4+ cell counts (using a conservative cut-off) [55, 65] and duration of infection to evaluate risk factors for recent infection compared to chronic infection.

Nonetheless, without an ideal assay in hand there is an immediate priority to develop new HIV incidence assays with improved specificity for more accurate estimates of recent infection and population-level incidence. If future assays demonstrate higher specificity compared to the BED assay, they could potentially be used independently or in a recent infection testing algorithm (RITA) with the BED assay, to improve the predictive value for detecting recent infection [61]. Though this algorithmic approach is attractive, it will add complexity and costs. Several new avidity-based assays are currently under development and require formal calibration studies to determine the duration of the assay's window period, validation against directly observed incidence measures from longitudinal cohort studies, and quantification of false-recent rates on chronic infections before they can be recommended for population-level incidence estimation.

Nearly three decades into the HIV/AIDS epidemic, we do not have suitable methods for measuring the most fundamental epidemiologic parameter, the number of new infections per year, i.e., the incidence. Clearly, market forces have not driven the development of HIV incidence assays, as the market demand for this niche assay is perceived to be small [75]. Additionally, the development, calibration, evaluation and validation of an incidence assay require large collections of well-characterized specimens from HIV seroconvertors and persons with long-standing infection with a variety of HIV-1 subtypes, from diverse geographic regions and with important co-morbidities. To date, there has not been a concerted effort to assemble these specimen panels and make them available to assay developers.

Over the past few years we have learned a great deal about HIV incidence estimation, especially with the use of incidence assays. More than ever before, we know what needs to be done to develop these important tools. It is critical that we now make the investment in developing the infrastructure, tools and methods required to yield reliable HIV incidence estimates. Failure to do this will hinder our efforts to decide how best to invest the future billions of dollars needed to limit the global HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored in part by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (for OL). Additional support provided by the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) sponsored by NIAID, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and Office of AIDS Research, of the NIH, DHHS (U01-AI-068613) (for OL and TDM), The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (for TDM), and The Wellcome Trust (for TBH). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Mishra V, Barrere B, Hong R, Khan S. Evaluation of bias in HIV seroprevalence estimates from national household surveys. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84 1:i63–i70. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reniers G, Eaton J. Refusal bias in HIV prevalence estimates from nationally representative seroprevalence surveys. AIDS. 2009;23:621–629. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283269e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherr L, Lopman B, Kakowa M, Dube S, Chawira G, Nyamukapa C, et al. Voluntary counselling and testing: uptake, impact on sexual behaviour, and HIV incidence in a rural Zimbabwean cohort. AIDS. 2007;21:851–860. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32805e8711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ades AE. Serial HIV seroprevalence surveys: interpretation, design, and role in HIV/AIDS prediction. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;9:490–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ades AE, Medley GF. Estimates of disease incidence in women based on antenatal or neonatal seroprevalence data: HIV in New York City. Stat Med. 1994;13:1881–1894. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown T, Salomon JA, Alkema L, Raftery AE, Gouws E. Progress and challenges in modelling country-level HIV/AIDS epidemics: the UNAIDS Estimation and Projection Package 2007. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84 1:i5–i10. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregson S, Donnelly CA, Parker CG, Anderson RM. Demographic approaches to the estimation of incidence of HIV-1 infection among adults from age-specific prevalence data in stable endemic conditions. AIDS. 1996;10:1689–1697. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199612000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Podgor MJ, Leske MC. Estimating incidence from age-specific prevalence for irreversible diseases with differential mortality. Stat Med. 1986;5:573–578. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780050604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saidel T, Sokal D, Rice J, Buzingo T, Hassig S. Validation of a method to estimate age-specific human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) incidence rates in developing countries using population-based seroprevalence data. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:214–223. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakarovitch C, Alioum A, Ekouevi DK, Msellati P, Leroy V, Dabis F. Estimating incidence of HIV infection in childbearing age African women using serial prevalence data from antenatal clinics. Stat Med. 2007;26:320–335. doi: 10.1002/sim.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNAIDS. Improved methods and assumptions for estimation of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and its impact: Recommendations of the UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates, Modelling and Projections. AIDS. 2002;16:W1–14. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200206140-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White RG, Vynnycky E, Glynn JR, Crampin AC, Jahn A, Mwaungulu F, et al. HIV epidemic trend and antiretroviral treatment need in Karonga District, Malawi. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:922–932. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams B, Gouws E, Wilkinson D, Karim SA. Estimating HIV incidence rates from age prevalence data in epidemic situations. Stat Med. 2001;20:2003–2016. doi: 10.1002/sim.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stover J, Walker N, Grassly NC, Marston M. Projecting the demographic impact of AIDS and the number of people in need of treatment: updates to the Spectrum projection package. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82 3:iii45–50. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gouws E, White PJ, Stover J, Brown T. Short term estimates of adult HIV incidence by mode of transmission: Kenya and Thailand as examples. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82 3:iii51–55. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallett TB, Zaba B, Todd J, Lopman B, Mwita W, Biraro S, et al. Estimating incidence from prevalence in generalised HIV epidemics: methods and validation. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e80. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hallett T. Estimating incidence from prevalence surveys: method, validation and application (PowerPoint presentation). The 2nd Global HIV/AIDS Surveillance Meeting; Bangkok, Thailand. March 2, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallett TB, Stover J, Mishra V, Ghys PD, Gregson S, Boerma T. Estimates of HIV incidence from household-based prevalence surveys. AIDS. 2010;24:147–152. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833062dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marston M, Harriss K, Slaymaker E. Non-response bias in estimates of HIV prevalence due to the mobility of absentees in national population-based surveys: a study of nine national surveys. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84 1:i71–i77. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy G, Parry JV. Assays for the detection of recent infections with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Euro Surveill. 2008;13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barin F, Nardone A. Monitoring HIV epidemiology using assays for recent infection: where are we? Euro Surveill. 2008;13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chawla A, Murphy G, Donnelly C, Booth CL, Johnson M, Parry JV, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody avidity testing to identify recent infection in newly diagnosed HIV type 1 (HIV-1)-seropositive persons infected with diverse HIV-1 subtypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:415–420. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01879-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Constantine NT, Sill AM, Jack N, Kreisel K, Edwards J, Cafarella T, et al. Improved classification of recent HIV-1 infection by employing a two-stage sensitive/less-sensitive test strategy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:94–103. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200301010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssen RS, Satten GA, Stramer SL, Rawal BD, O'Brien TR, Weiblen BJ, et al. New testing strategy to detect early HIV-1 infection for use in incidence estimates and for clinical and prevention purposes. JAMA. 1998;280:42–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kothe D, Byers RH, Caudill SP, Satten GA, Janssen RS, Hannon WH, Mei JV. Performance characteristics of a new less sensitive HIV-1 enzyme immunoassay for use in estimating HIV seroincidence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:625–634. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Ketema F, Sill AM, Kreisel KM, Cleghorn FR, Constantine NT. A simple and inexpensive particle agglutination test to distinguish recent from established HIV-1 infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parekh BS, Kennedy MS, Dobbs T, Pau CP, Byers R, Green T, et al. Quantitative detection of increasing HIV type 1 antibodies after seroconversion: a simple assay for detecting recent HIV infection and estimating incidence. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2002;18:295–307. doi: 10.1089/088922202753472874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suligoi B, Butto S, Galli C, Bernasconi D, Salata RA, Tavoschi L, et al. Detection of recent HIV infections in African individuals infected by HIV-1 non-B subtypes using HIV antibody avidity. J Clin Virol. 2008;41:288–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei X, Liu X, Dobbs T, Kuehl D, Nkengasong JN, Hu DJ, Parekh BS. Development of Two Avidity-Based Assays to Detect Recent HIV Type 1 Seroconversion Using a Multisubtype gp41 Recombinant Protein. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2010 doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson KM, Johnson EI, Croom HA, Richards KM, Doughty L, Cunningham PH, et al. Incidence immunoassay for distinguishing recent from established HIV-1 infection in therapy-naive populations. AIDS. 2004;18:2253–2259. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rawal BD, Degula A, Lebedeva L, Janssen RS, Hecht FM, Sheppard HW, Busch MP. Development of a new less-sensitive enzyme immunoassay for detection of early HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:349–355. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200307010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schupbach J, Gebhardt MD, Tomasik Z, Niederhauser C, Yerly S, Burgisser P, et al. Assessment of recent HIV-1 infection by a line immunoassay for HIV-1/2 confirmation. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parekh BS, Hu DJ, Vanichseni S, Satten GA, Candal D, Young NL, et al. Evaluation of a sensitive/less-sensitive testing algorithm using the 3A11-LS assay for detecting recent HIV seroconversion among individuals with HIV-1 subtype B or E infection in Thailand. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:453–458. doi: 10.1089/088922201750102562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Vu S, Pillonel J, Semaille C, Bernillon P, Le Strat Y, Meyer L, Desenclos JC. Principles and uses of HIV incidence estimation from recent infection testing--a review. Euro Surveill. 2008;13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young CL, Hu DJ, Byers R, Vanichseni S, Young NL, Nelson R, et al. Evaluation of a sensitive/less sensitive testing algorithm using the bioMerieux Vironostika-LS assay for detecting recent HIV-1 subtype B′ or E infection in Thailand. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:481–486. doi: 10.1089/088922203766774522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang Y, Wang M, Ni M, Duan S, Wang Y, Feng J, et al. HIV-1 incidence estimates using IgG-capture BED-enzyme immunoassay from surveillance sites of injection drug users in three cities of China. AIDS. 2007;21 8:S47–51. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304696.62508.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim A, McDougal S, Hargrove J, et al. Toward more plausible estimates of HIV-1 incidence in cross-sectional serologic surveys in Africa: Application of a HIV-1 incidence assay with post-assay adjustments. Paper presented at: 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 25-28, 2007; Los Angeles, California. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rehle T, Shisana O, Pillay V, Zuma K, Puren A, Parker W. National HIV incidence measures--new insights into the South African epidemic. S Afr Med J. 2007;97:194–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saphonn V, Parekh BS, Dobbs T, Mean C, Bun LH, Ly SP, et al. Trends of HIV-1 seroincidence among HIV-1 sentinel surveillance groups in Cambodia, 1999-2002. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:587–592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolday D, Meles H, Hailu E, Messele T, Mengistu Y, Fekadu M, et al. Temporal trends in the incidence of HIV infection in antenatal clinic attendees in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1995-2003. J Intern Med. 2007;261:132–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mermin J, Musinguzi J, Opio A, Kirungi W, Ekwaru JP, Hladik W, et al. Risk factors for recent HIV infection in Uganda. JAMA. 2008;300:540–549. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao Y, Jiang Y, Feng J, Xu W, Wang M, Funkhouser E, et al. Seroincidence of recent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections in China. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:1384–1386. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00356-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karita E, Price M, Hunter E, Chomba E, Allen S, Fei L, et al. Investigating the utility of the HIV-1 BED capture enzyme immunoassay using cross-sectional and longitudinal seroconverter specimens from Africa. AIDS. 2007;21:403–408. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801481b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDougal JS, Parekh BS, Peterson ML, Branson BM, Dobbs T, Ackers M, Gurwith M. Comparison of HIV type 1 incidence observed during longitudinal follow-up with incidence estimated by cross-sectional analysis using the BED capture enzyme immunoassay. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:945–952. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hargrove JW, Humphrey JH, Mutasa K, Parekh BS, McDougal JS, Ntozini R, et al. Improved HIV-1 incidence estimates using the BED capture enzyme immunoassay. AIDS. 2008;22:511–518. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2a960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.UNAIDS. Statement on the use of the BED-assay for the estimation of HIV-1 incidence for surveillance or epidemic monitoring. Edited by Meeting of the UNAIDS/WHO Reference Group on Estimates MaP; Athens, Greece. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McWalter TA, Welte A. Relating recent infection prevalence to incidence with a sub-population of assay non-progressors. J Math Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00285-009-0282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welte A, McWalter TA, Barnighausen T. A Simplified Formula for Inferring HIV Incidence from Cross-Sectional Surveys Using a Test for Recent Infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:125–126. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brookmeyer R. Should biomarker estimates of HIV incidence be adjusted? AIDS. 2009;23:485–491. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283269e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hargrove JW. BED estimates of HIV incidence must be adjusted. AIDS. 2009;23:2061–2062. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832f3d8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McDougal JS. BED estimates of HIV incidence must be adjusted. AIDS. 2009;23:2064–2065. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832eff6e. author reply 2066-2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Welte A, M TA, Barnighausen T. Reply to ‘Should biomarker estiamtes of HIV incidence be adjusted?’. AIDS. 2009;23:2062–2063. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832eff59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Office of Global AIDS Coordinator (OGAC) Interim Recommendations for the Use of the ED Capture Enzyme Immunoassay for Incidence Estimatino and Surveillance - Statement from the Surveillance and Survey and the Laboratory Working Groups to the Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator. Washington, DC: OGAC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oluoch T. Preliminary analysis of recent HIV infection in Kenya, KAIS 2007 (PowerPoint presentation). The 2nd Global HIV/AIDS Surveillance Meeting; Bangkok, Thailand. March 2, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akarasewi P. Overview of the HIV epidemic and the National AIDS Surveillance (PowerPoint presentation). The 2nd Global HIV/AIDS Surveillance Meeting; Bangkok, Thailand. March 2, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Welte A, M T. Methodological Progress in Estimating Incidence with a Test for Recent Infection. Paper presented at the 2nd Global HIV/AIDS Surveillance Meeting; Bangkok, Thailand. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hallett TB, Ghys P, Barnighausen T, Yan P, Garnett GP. Errors in ‘BED’-derived estimates of HIV incidence will vary by place, time and age. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hladik W, Olara D, Were W, Mermin J, Downing R. The effect of antiretroviral treatment on the specificity of the serological BED HIV-1 incidence assay. HIV Implementers Meeting; Kigali, Rwanda. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barnighausen T, Wallrauch C, Welte A, McWalter TA, Mbizana N, Viljoen J, et al. HIV incidence in rural South Africa: comparison of estimates from longitudinal surveillance and cross-sectional cBED assay testing. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Laeyendecker O. BED+ avidity testing algorithm for incidence estimates in Uganda (PowerPoint presentation). The 2nd Global HIV/AIDS Surveillance Meeting; Bangkok, Thailand. March 2, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marinda ET, Hargrove J, Preiser W, Slabbert H, van Zyl G, Levin J, et al. Significantly Diminished Long-Term Specificity of the BED Capture Enzyme Immunoassay Among Patients with HIV-1 With Very Low CD4 Counts and Those on Antiretroviral Therapy. JAIDS. 2009 September; doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181b61938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hladik W, Olara D, Were W, Mermin J, Downing R. The effect of antiretroviral treatment on the specificity of the serological BED HIV-1 incidence assay. 2007 HIV/AIDS Implementers Meeting; Kigali, Rwanda. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laeyendecker O, O A, Neal J, Gamiel J, Kraus C, Eshleman SH, Owen SM, Shahan J, Kelen G, Quinn TC. Decreasing HIV incidence and prevalence at the Johns Hopkins Emergency Department with a concurrent increase of virally-suppressed HIV-infected individuals. CROI; Montreal, Canada. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martro E, Suligoi B, Gonzalez V, Bossi V, Esteve A, Mei J, Ausina V. Comparison of the avidity index method and the serologic testing algorithm for recent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) seroconversion, two methods using a single serum sample for identification of recent HIV infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:6197–6199. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.6197-6199.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gilks CF, Crowley S, Ekpini R, Gove S, Perriens J, Souteyrand Y, et al. The WHO public-health approach to antiretroviral treatment against HIV in resource-limited settings. Lancet. 2006;368:505–510. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Romero A, Gonzalez V, Granell M, Matas L, Esteve A, Martro E, et al. Recently acquired HIV infection in Spain (2003-2005): introduction of the serological testing algorithm for recent HIV seroconversion. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:106–110. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Laeyendecker O, Rothman RE, Henson C, Horne BJ, Ketlogetswe KS, Kraus CK, et al. The effect of viral suppression on cross-sectional incidence testing in the johns hopkins hospital emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48:211–215. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181743980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Novitsky V, Wang R, Kebaabetswe L, Greenwald J, Rossenkhan R, Moyo S, et al. Better Control of Early Viral Replication Is Associated With Slower Rate of Elicited Antiviral Antibodies in the Detuned Enzyme Immunoassay During Primary HIV-1C Infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab6ef0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS. Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; Jun 25-27, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ghys PD, Kufa E, George MV. Measuring trends in prevalence and incidence of HIV infection in countries with generalised epidemics. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82 1:i52–56. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.016428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hallett T. Estimating incidence from prevalence surveys: method, validation and application (PowerPoint presentation). The 2nd Global HIV/AIDS Surveillance Meeting; Bangkok, Thailand. March 2, 2009; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Macro International Inc. HIV Prevalence Estimates from the Demographic and Health Surveys. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Diaz T, Garcia-Calleja JM, Ghys PD, Sabin K. Advances and future directions in HIV surveillance in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4:253–259. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832c1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mastro TD. HIV incidence determination update from the WHO Working Group (PowerPoint presentation). The 2nd Global HIV/AIDS Surveillance Meeting; Bangkok, Thailand. March 2, 2009. [Google Scholar]