Abstract

Recombinant proteins typically include one or more affinity tags to facilitate purification and/or detection. Expression constructs with affinity tags often include an engineered protease site for tag removal. Like other enzymes, the activities of proteases can be affected by buffer conditions. The buffers used for integral membrane proteins contain detergents, which are required to maintain protein solubility. We examined the detergent sensitivity of six commonly-used proteases (Enterokinase, Factor Xa, Human Rhinovirus 3C Protease, SUMOstar, Tobacco Etch Virus Protease, and Thrombin) by use of a panel of ninety-four individual detergents. Thrombin activity was insensitive to the entire panel of detergents, thus suggesting it as the optimal choice for use with membrane proteins. Enterokinase and Factor Xa were only affected by a small number of detergents, making them good choices as well.

Keywords: Proteases, detergent stability, membrane proteins

Introduction

Modern recombinant protein expression constructs include one or more affinity tags to aid in purification and/or detection. After serving its requisite function(s), the tag is often removed so as not to (potentially) interfere with “downstream” protein applications such as functional or structural studies. Three-dimensional crystallization, for structure determination by x-ray crystallography, is often deleteriously affected by inclusion of the disordered or flexible affinity tag. An engineered site for a specific protease in the linker region between tag(s) and native protein is thus included to facilitate tag removal. Common proteases include Enterokinase [1], Factor Xa [2], Human Rhinovirus 3C Protease (1 HRV 3C) [3], SUMO Protease [4], Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) Protease [5], and Thrombin [6, 7].Table 1 lists the canonical recognition sequences, and specific cut-sites, for each of these proteases. For constructs containing an N-terminal tag with a protease site in the linker, Enterokinase, Factor Xa, and SUMOstar will return the original (parent) protein, while HRV3C, Thrombin, and TEV leave several residues of the protease site. TEV is the most widely-used of these proteases [8–11]. In addition to its high specificity, TEV maintains activity in a wide range of buffer and solution conditions, and is readily capable of being produced in-house.

Table 1.

Proteases used in this study.

| Protease | Cleavage Site |

|---|---|

| Enterokinase | Asp-Asp-Asp-Lys▾ |

| Factor Xa | Ile-Glu/Asp-Gly-Arg▾ |

| HRV3C | Leu-Glu-Val-Leu-Phe-Gln▾ Gly-Pro |

| SUMOstar | Recognizes tertiary structure of SUMOstar tag (10kDa) |

| TEV | Glu-Asn-Leu-Tyr-Phe-Gln▾ Gly/Ser |

| Thrombin | Leu-Val-Pro-Arg▾ Gly-Ser |

The amino acid recognition site for each protease is provided with the site of cleavage indicated by the

All protease recognize short, linear sequences while SUMOstar recognizes the tertiary structure of the SUMOstar tag.

Several other considerations can influence the choice of protease for removal of affinity tags. Protease specificity can vary widely. Digestive and coagulation proteases can (and do) cleave proteins at sites other than the engineered “cut-site”; examples of this include non-specific proteolysis of recombinant proteins by enterokinase [12], thrombin [13] and factor Xa [13]. To quote, “It is necessary to characterize the protein of interest after cleavage from the affinity label to assure that there are no changes in the covalent structure of the protein of interest [13].” Typically, this characterization method would be mass spectrometry, and reliable methods of sample preparation have been developed for integral membrane proteins [14]. In contrast, viral proteases (e.g. HRV3C and TEV) are very highly specific [15, 16]. However, viral proteases typically possess turnover rates that are very much lower, as much as 104 lower, than those of non-viral proteases [17]. The much lower activity of viral proteases is reflected, empirically, in the observation that those labs which utilize it for “large-scale” protein production (for x-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy) commonly make their own HRV3C and/or TEV for use. Therefore, the selection of non-viral vs. viral proteases, for removal of affinity tags from recombinant fusion proteins, is, essentially, a trade-off between specificity and activity.

Maintaining the solubility of integral membrane proteins in aqueous solution requires the presence of detergents or other surfactants [18]. These detergents, present at concentrations above the critical micelle concentration (CMC), form a protein-detergent complex (PDC) with the membrane protein [19]. Detergents can have inhibitory effects upon proteases; in one example, we previously demonstrated that several detergents inhibit TEV [20]. The inability of TEV to efficiently remove an affinity tag in a particular detergent is troublesome and unfortunately precludes the universal use of TEV for membrane proteins. Many detergents and detergent mixtures are, in principle, possible candidates for use with membrane proteins. Also, as mentioned, multiple proteases besides TEV are commonly used. In practice, when a protease does not remove the affinity tag of a membrane protein, two possibilities (that are not mutually exclusive) for this failure exist. The tag could be sterically inaccessible to the protease because of the protein, the detergent, or both. Or, the protease could be inhibited by the detergent. In order to eliminate this situation of “one equation with two unknowns”, we characterized the sensitivities of a set of proteases (Enterokinase, Factor Xa, HRV 3C, SUMOstar, TEV, and Thrombin) to a large number (ninety-four) of individual detergents. This detergent panel was recently compiled in conjunction with our recent development of a high-throughput assay for screening the stability and size of a PDC in multiple detergents[21].

Materials and Methods

Materials

Enterokinase, Factor Xa, HRV 3C, and Thrombin along with their respective cleavage control proteins were purchased from EMD Biosciences; SUMOstar and its cleavage control protein were obtained from LifeSensors, Inc. We made TEV “in-house” using published methods [22]; the cleavage control protein is a protein domain on which we work[23], and its affinity tag is quantitatively removed by TEV[24]. Detergents were from Anatrace, Avanti Polar Lipids, EMD Biosciences, or Bachem. Electrophoresis and blotting was performed with E-PAGE 48-well 8% gels and iBLOT nitrocellulose transfer stacks (Invitrogen), and visualized with colloidal gold total protein stain (Bio-Rad).

Protease Digestion

Enterokinase (1:50dilution, 4hr digest, 1μg control protein/well); Factor Xa (1:50dilution, 4hr digest, 2μg control protein/well); HRV 3C (1:50dilution, 4hr digest, 1μg control protein/well); SUMOstar (1:50dilution, 4hr digest, 2μg control protein/well); TEV (36ng/μl, overnight digest, 5μg control protein/well); Thrombin (1:35dilution, 4hr digest, 1μg control protein/well). The reaction and dilution buffers were made from the concentrated commercial stocks accompanying the proteases except for TEV where the buffer (100mM Tris pH 8, 1mM EDTA, 2mM DDT) was prepared. Two samples were made in 96 well PCR plates based on the above conditions. Plate1 contained control protein and the detergent while Plate2 consisted of the control protein, detergent, and 1μl of the diluted protease. The final volume of each well was 15μl. Plates were gently shaken at 25°C/300rpm in an Eppendorf Thermomixer. After the digestion was complete, 5μl of 4X E-PAGE loading dye was added to each plate. Samples were then loaded on a 48-well E-PAGE gel, blotted to a nitrocellulose membrane using the iBLOT apparatus, and visualized with colloidal gold stain.

Results and Discussion

In order to assess the activity of commonly used proteases in our detergent panel, we digested soluble proteins containing the appropriate protease cleavage site. The experimental design presented here is similar to our previous study of the detergent sensitivity of TEV [20].We note that a report from another laboratory utilized three different membrane proteins as test proteins [25]. We have chosen to use soluble proteins for several reasons: 1) a test membrane protein would have to be stable in every detergent in the panel to be a reliable test protein, and 2) a protease site on a membrane protein might be occluded by the detergent of the PDC, while a soluble protein should not interact with detergent and is thus much less likely to have its protease site occluded by detergent. Moreover, in this present study, the use of vendor-supplied positive control proteins obviates the possibility of the protein occluding the cleavage site.

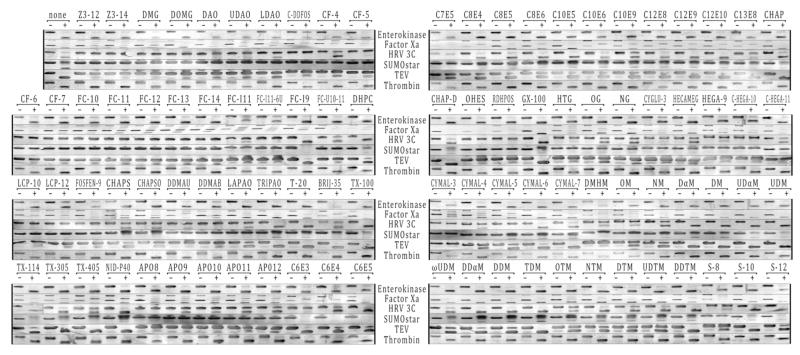

Figure 1 shows a composite of the protein gels used to evaluate the protease activity in the detergent panel. The relative activities of each protease were estimated from the amount of cleavage product observed on the protein gels and is summarized in Table 2. The best protease was Thrombin which has maximum activity in all of the detergents tested, followed closely by Enterokinase and Factor Xa while HRV 3C and SUMOstar were drastically affected by detergent. TEV possessed activity in most detergents, but at low levels in a large percentage of these detergents. Since TEV is typically made as a reagent in-house, more can be added to a cleavage reaction to possibly overcome the inhibitory effect of a particular detergent. The poor performance of SUMOstar was somewhat surprising, since this protease recognizes the tertiary structure of the large SUMOstar tag [4] compared to the short recognition sequences of the other proteases tested. The SUMOstar tag may be partially unfolded in detergent micelle solutions or may possibly insert into the micelle, making it unavailable for binding the SUMOstar protease.

Figure 1.

Gel lanes for each protease experiment are shown above labeled “–” for no protease and “+” for protease present. The abbreviations for the detergents are given in Table 2. The rows were cut out from scanned images of the 48-well blots and their contrast was adjusted automatically within Adobe Photoshop CS2. All control protease control proteins showed a simple gel shift after digestion with the exception of the Factor Xa control protein which formed SDS-resistant oligomers. These oligomers did not prevent analysis of the results. The amount of digestion was estimated from the amount of digested protein formed in the protease “+” lane compared to the protease “–” lane and assigned a value of “+++, ++, +, or –”. The image for TX-114 for HRV3C was repeated from another blot due to a bubble in the original transfer.

Table 2.

Summary of detergent sensitivity of proteases.

| Name | [Det] mM | Abbrev. | Enterokinase | Factor Xa | HRV 3C | SUMOstar | TEV | Thrombin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZWITTERGENT®3–12 | 8.4 (2.8) | Z3–12 | ||||||

| ZWITTERGENT®3–14 | 10 (0.2) | Z3–14 | ||||||

| n-Decyl-N,N-dimethylglycine | 38 (19) | DMG | ||||||

| n-Dodecyl-N,N-dimethylglycine | 4.5(1.5) | DOMG | ||||||

| n-Decyl-N,N-dimethylamine-N-oxide | 21 (10.5) | DAO | ||||||

| n-Undecyl-N,N,-dimethylamine-N-oxide | 9.6 (3.2) | UDAO | ||||||

| n-Dodecyl-N,N-dimethylamine-N-oxide | 3 (1) | LDAO | ||||||

| C-DODECAFOS™ | 44 (22) | C-DDFOS | ||||||

| CYCL0F0S™-4 | 28 (14) | CF-4 | ||||||

| CYCL0F0S™-5 | 13.5 (4.5) | CF-5 | ||||||

| CYCL0F0S™-6 | 8.04 (2.68) | CF-6 | ||||||

| CYCL0F0S™-7 | 6.2 (0.62) | CF-7 | ||||||

| FOS-CHOLINE®-10 | 22 (11) | FC-10 | ||||||

| F0S-CH0LINE®-11 | 5.55 (1.85) | FC-11 | ||||||

| F0S-CH0LINE®-12 | 4.5 (1.5) | FC-12 | ||||||

| F0S-CH0LINE®-13 | 7.5 (0.75) | FC-13 | ||||||

| F0S-CH0LINE®-14 | 6 (0.12) | FC-14 | ||||||

| F0S-CH0LINE®-IS0-11 | 53.2 (26.6) | FC-I11 | ||||||

| F0S-CH0LINE®-IS0-11-6U | 51.6 (25.8) | FC-I11-6U | ||||||

| F0S-CH0LINE®-IS0-9 | 64 (32) | FC-I9 | ||||||

| FOS-CHOLINE®-UNSAT-11-10 | 15.5 (6.2) | FC-U10-11 | ||||||

| 1,2-Diheptanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine | 4.2 (1.4) | DHPC | ||||||

| LysoPC-10 | 20 (8) | LPC-10 | ||||||

| LysoPC-12 | 7 (0.7) | LPC-12 | ||||||

| F0SFEN™-9 | 4.05 (1.35) | FOSFEN-9 | ||||||

| CHAPS | 20 (8) | CHAPS | ||||||

| CHAPSO | 20 (8) | CHAPSO | ||||||

| n-Dodecvl-N,N-(dimethylammonio)undecanoate | 6.5 (0.13) | DDMAU | ||||||

| n-Dodecyl-N,N-(dimethylammonio)butyrate | 12.9 (4.3) | DDMAB | ||||||

| LAPAO | 4.8 (1.6) | LAPAO | ||||||

| TRIPAO | 13.5 (4.5) | TRIPAO | ||||||

| TWEEN®20 | 5.9 (0.059) | T-20 | ||||||

| BRIJ®35 | 9.1 (0.091) | BRIJ-35 | ||||||

| TRITON®X-10 | 11.5 (0.23) | TX-10 | ||||||

| TRITON®X-114 | 10 (0.2) | TX-114 | ||||||

| TRITON®X-305 | 6.5 (0.65) | TX-305 | ||||||

| TRITON®X-405 | 8.1 (0.81) | TX-405 | ||||||

| [Octylphenoxy] polyethoxyethanol | 15 (0.3) | NID-P40 | ||||||

| Dimethyloctylphosphine oxide | 80 (40) | AP08 | ||||||

| Dimethylnonylphosphine oxide | 20 (10) | AP09 | ||||||

| Dimethyldecylphosphine oxide | 14.0 (4.7) | APO10 | ||||||

| Dimethylundecylphosphine oxide | 3.6 (1.2) | AP011 | ||||||

| Dimethyldodecylphosphine oxide | 5.7 (0.57) | AP012 | ||||||

| Triethylene glycol monohexyl ether | 46 (23) | C6E3 | ||||||

| Tetraethylene glycol monohexyl ether | 60 (30) | C6E4 | ||||||

| Pentaethylene glycol monohexyl ether | 74 (37) | C6E5 | ||||||

| Pentaethylene glycol monoheptyl ether | 42 (21) | C7E5 | ||||||

| Tetraethylene glycol monooctyl ether | 20 (8) | C8E4 | ||||||

| Pentaethylene glycol monooctyl ether | 17.75 (7.1) | C8E5 | ||||||

| Hexaethylene glycol monooctyl ether | 25 (10) | C8E6 | ||||||

| Pentaethylene glycol monodecyl ether | 8.1 (0.81) | C10E5 | ||||||

| Hexaethylene glycol monodecyl ether | 9 (0.9) | C10E6 | ||||||

| Polyoxyethylene(9)decyl ether | 3.9 (1.3) | C10E9 | ||||||

| Octaethylene glycol monododecyl ether | 9 (0.09) | C12E8 | ||||||

| Polyoxyethylene(9)dodecyl ether | 5 (0.05) | C12E9 | ||||||

| Polyoxyethylene(10)dodecyl ether | 10 (0.2) | C12E10 | ||||||

| Polyoxyethylene(8)tridecyl ether | 10 (0.1) | C13E8 | ||||||

| Big CHAP | 8.7 (2.9) | CHAP | ||||||

| Big CHAP, deoxy | 4.2 (1.4) | CHAP-D | ||||||

| Octyl-2-hydroxyethyl-sulfoxide | 48.4 (24.2) | OHES | ||||||

| Rac-2,3-dihydroxypropyloctylsulfoxide | 48.4 (24.2) | RDHPOS | ||||||

| Genapol®X-100 | 7.5 (0.15) | GX-100 | ||||||

| n-Heptyl-β-D-thioglucopyranoside | 58 (29) | HTG | ||||||

| n-Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | 36 (18) | OG | ||||||

| n-Nonyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | 16.25 (6.5) | NG | ||||||

| CYGLU®-3 | 56 (28) | CYGLU-3 | ||||||

| HECAMEG | 39 (19.5) | HECAMEG | ||||||

| Hega®-9 | 78 (39) | HEGA-9 | ||||||

| C-Hega®-10 | 70 (35) | C-HEGA-10 | ||||||

| C-Hega®-11 | 23 (11.5) | C-HEGA-11 | ||||||

| CYMAL®-3 | 60 (30) | CYMAL-3 | ||||||

| CYMAL®-4 | 19 (7.6) | CYMAL-4 | ||||||

| CYMAL®-5 | 7.2 (2.4) | CYMAL-5 | ||||||

| CYMAL®-6 | 5.6 (0.56) | CYMAL-6 | ||||||

| CYMAL®-7 | 9.5 (0.19) | CYMAL-7 | ||||||

| 2,6-Dimethyl-4-heptyl-β-D-maltoside | 55 (27.5) | DMHM | ||||||

| n-Octyl-β-D-maltopyranoside | 39 (19.5) | OM | ||||||

| n-Nonyl-β-D-maltopyranoside | 15 (6) | NM | ||||||

| n-Decyl-α-D-maltopyranoside | 4.8 (1.6) | DαM | ||||||

| n-Decyl-β-D-maltopyranoside | 5.4 (1.8) | DM | ||||||

| n-Undecyl-α-D-maltopyranoside | 5.8 (0.58) | UDαM | ||||||

| n-Undecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside | 5.9 (0.59) | UDM | ||||||

| ω-Undecylenyl-β-D-maltopyranoside | 3.6 (1.2) | ωUDM | ||||||

| n-Dodecyl-α-D-maltopyranoside | 7.5 (0.15) | DDαM | ||||||

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside | 8.5 (0.17) | DDM | ||||||

| n-Tridecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside | 1.5 (0.03) | TDM | ||||||

| n-Octyl-β-D-thiomaltopyranoside | 21.25 (8.5) | OTM | ||||||

| n-Nonyl-β-D-thiomaltopyranoside | 9.6 (3.2) | NTM | ||||||

| n-Decyl-β-D-thiomaltopyranoside | 9 (0.9) | DTM | ||||||

| n-Undecyl-β-D-thiomaltopyranoside | 10.5 (0.21) | UDTM | ||||||

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-thiomaltopyranoside | 5 (0.05) | DDTM | ||||||

| Sucrose8 | 48.8 (24.4) | S-8 | ||||||

| Sucrose10 | 7.5 (2.5) | S-10 | ||||||

| Sucrose12 | 15 (0.3) | S-12 |

The membrane protein detergent panel is shown above. The values in parenthesis in the [Det] column are the CMC values for each detergent. Detergents in bold were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, italics from Bachem, underlined from EMD Biosciences, and all others from Anatrace. The legend shows the relative protease activity in each detergent based on the amount of cleavage product observed on the protein gel.

Conclusion

Based upon our data, the activity of Thrombin is not significantly affected by any of the ninety-four detergents of our panel [21]. This panel encompasses, as single detergents in individual solutions, nearly all of the detergents utilized in membrane protein biochemistry, biophysics and structural biology (at present). Therefore, we recommend the design and utilization of a thrombin cleavage site for protein expression constructs; this will provide for the most detergent-invariant affinity tag removal. Moreover, Enterokinase and Factor Xa were only affected by a small number of detergents, making them good choices as well. Additionally, removal of an N-terminal affinity-binding site by Enterokinase or Factor Xa produces the wildtype (or parent) construct protein free from any extraneous residues derived from the protease recognition site. This attribute may be (very) advantageous; for example, a crystal contact mediated through the N-terminus could be disrupted by the presence of these extra residues.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by NIH Roadmap Grant 5R01 GM075931 (to M.C.W.).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: CMC, critical micelle concentration; DTT, Dithiothreitol; EDTA, Ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid; HRV 3C, Human Rhinovirus 3C Protease; PAGE; Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; PDC, protein-detergent complex; SUMO, Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier; TEV, Tobacco Etch Virus Protease.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Choi SI, Song HW, Moon JW, Seong BL. Recombinant enterokinase light chain with affinity tag: expression from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its utilities in fusion protein technology. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001;75:718–724. doi: 10.1002/bit.10082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith DB, Johnson KS. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene. 1988;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr S, Miller J, Leary SE, Bennett AM, Ho A, Williamson ED. Expression of a recombinant form of the V antigen of Yersinia pestis, using three different expression systems. Vaccine. 1999;18:153–159. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malakhov MP, Mattern MR, Malakhova OA, Drinker M, Weeks SD, Butt TR. SUMO fusions and SUMO-specific protease for efficient expression and purification of proteins. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2004;5:75–86. doi: 10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029237.70316.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parks TD, Leuther KK, Howard ED, Johnston SA, Dougherty WG. Release of proteins and peptides from fusion proteins using a recombinant plant virus proteinase. Anal Biochem. 1994;216:413–417. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sticha KR, Sieg CA, Bergstrom CP, Hanna PE, Wagner CR. Overexpression and large-scale purification of recombinant hamster polymorphic arylamine N-acetyltransferase as a dihydrofolate reductase fusion protein. Protein Expr Purif. 1997;10:141–153. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vothknecht UC, Kannangara CG, von Wettstein D. Expression of catalytically active barley glutamyl tRNAGlu reductase in Escherichia coli as a fusion protein with glutathione S-transferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9287–9291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabrita LD, Gilis D, Robertson AL, Dehouck Y, Rooman M, Bottomley SP. Enhancing the stability and solubility of TEV protease using in silico design. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2360–2367. doi: 10.1110/ps.072822507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapust RB, Routzahn KM, Waugh DS. Processive degradation of nascent polypeptides, triggered by tandem AGA codons, limits the accumulation of recombinant tobacco etch virus protease in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) Protein Expr Purif. 2002;24:61–70. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nallamsetty S, Kapust RB, Tozser J, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. Efficient site-specific processing of fusion proteins by tobacco vein mottling virus protease in vivo and in vitro. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;38:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Berg S, Lofdahl PA, Hard T, Berglund H. Improved solubility of TEV protease by directed evolution. J Biotechnol. 2006;121:291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liew OW, Ching Chong JP, Yandle TG, Brennan SO. Preparation of recombinant thioredoxin fused N-terminal proCNP: Analysis of enterokinase cleavage products reveals new enterokinase cleavage sites. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenny RJ, Mann KG, Lundblad RL. A critical review of the methods for cleavage of fusion proteins with thrombin and factor Xa. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;31:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(03)00168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cadene M, Chait BT. A robust, detergent-friendly method for mass spectrometric analysis of integral membrane proteins. Anal Chem. 2000;72:5655–5658. doi: 10.1021/ac000811l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cordingley MG, Callahan PL, Sardana VV, Garsky VM, Colonno RJ. Substrate requirements of human rhinovirus 3C protease for peptide cleavage in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9062–9065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapust RB, Tozser J, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. The P1′ specificity of tobacco etch virus protease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:949–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babe LM, Craik CS. Viral proteases: evolution of diverse structural motifs to optimize function. Cell. 1997;91:427–430. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiener MC. Existing and emergent roles for surfactants in the three-dimensional crystallizatio of integral membrane proteins. Curr. Opin. Colloid & Interface Sci. 2001;6:412–419. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiener MC. A pedestrian guide to membrane protein crystallization. Methods. 2004;34:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohanty AK, Simmons CR, Wiener MC. Inhibition of tobacco etch virus protease activity by detergents. Protein Expression & Purification. 2003;27:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00589-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vergis JM, Purdy MD, Wiener MC. A high-throughput differential filtration assay to screen and select detergents for membrane proteins. Anal Biochem. 2010;407:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tropea JE, Cherry S, Waugh DS. Expression and purification of soluble His(6)-tagged TEV protease. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;498:297–307. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shultis DD, Purdy MD, Banchs CN, Wiener MC. Outer membrane active transport: structure of the BtuB:TonB complex. Science. 2006;312:1396–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1127694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shultis DD, Purdy MD, Banchs CN, Wiener MC. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of the Escherichia coli outer membrane cobalamin transporter BtuB in complex with the carboxy-terminal domain of TonB. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2006;62:638–641. doi: 10.1107/S1744309106018240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundback AK, van den Berg S, Hebert H, Berglund H, Eshaghi S. Exploring the activity of tobacco etch virus protease in detergent solutions. Anal Biochem. 2008;382:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]