Abstract

Treatment with anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) throughout adolescence facilitates offensive aggression in Syrian hamsters. In the anterior hypothalamus (AH), the dopaminergic neural system undergoes alterations after repeated exposure to AAS producing elevated aggression. Previously, systemic administration of selective dopamine receptor antagonists has been shown to reduce aggression in various species and animal models. However, these reductions in aggression occur with concomitant alterations in general arousal and mobility. Therefore, in order to control for these systemic effects, the current studies utilized microinjection techniques to determine the effects of local antagonism of D2 and D5 receptors in the AH on adolescent AAS-induced aggression. Male Syrian hamsters were treated with AAS throughout adolescence and tested for aggression after local infusion of the D2 antagonist eticlopride, or the D5 antagonist SCH-23390, into the AH. Treatment with eticlopride showed dose-dependent suppression of aggressive behavior in the absence of changes in mobility. Conversely, while injection of SCH-23390 suppressed aggressive behavior, these reductions were met with alterations in social interest and locomotor behavior. To elucidate a plausible mechanism for the observed D5 receptor mediation of AAS-induced aggression, brains of AAS and sesame oil-treated animals were processed for double-label immunofluorescence of GAD67 (a marker for GABA production) and D5 receptors in the lateral subdivision of the AH (LAH). Results indicate a sparse distribution of GAD67 neurons colocalized with D5 receptors in the LAH. Together, these results indicate that D5 receptors in the LAH modulate non-GABAergic pathways that indirectly influence aggression control, while D2 receptors have a direct influence on AAS-induced aggression.

Key Terms: lateral anterior hypothalamus, dopamine D2 and D5 receptors, anabolic-androgenic steroids, offensive aggression, adolescence, Syrian hamster

Introduction

Adolescence is a developmental period where neurobiological mechanisms regulating complex behaviors, such as aggression, are particularly sensitive to circulating androgens. For example, an increased incidence of aggressive behavior correlates with elevated levels of endogenous testosterone in mid-to-late adolescent males (Dabbs, Frady, Carr, & Besch, 1987; Dabbs, Jurkovic, & Frady, 1991; Mattsson, Schalling, Olweus, Low, & Svensson, 1980; Scerbo & Kolko, 1994) but not in prepubertal males (Constantino et al., 1993; Schaal, Tremblay, Soussignan, & Susman, 1996; Susman et al., 1987), suggesting a link between circulating androgens and the development of the aggressive phenotype. This notion is concerning given that abuse of synthetic testosterone and its derivatives, collectively termed anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS), has remained high in adolescent populations (NIDACapsules, 2008). This pattern of early use has been associated with continued and frequent abuse later in life despite potential psychiatric, physiological, and behavioral risks, including heightened offensive aggression (Buckley et al., 1988).

For more than a decade, the Syrian hamster has been used as a valid animal model to investigate the neurobiological and behavioral consequences of adolescent AAS-abuse (Melloni, Connor, Hang, Harrison, & Ferris, 1997). This research has led to a plausible model underscoring the major neurochemical alterations produced in various brain loci that contribute to the AAS-induced aggressive phenotype (for review see Melloni & Ricci, 2009). Of particular interest is the anterior hypothalamus (AH), a brain region at the center of aggression control sharing reciprocal connections with other hypothalamic and limbic nuclei (Delville, De Vries, & Ferris, 2000). Within the AH, various neurochemical systems are integrated and altered with adolescent exposure to AAS resulting in changes in aggression response. Recently, attention has been drawn to the role of dopamine in the control of AAS-induced aggression. Specifically, animals treated with AAS throughout adolescence have significantly increased levels of tyrosine hydroxylase (the rate limiting enzyme for the production of dopamine) in the AH (Ricci, Schwartzer, & Melloni, 2009). These increases in dopamine production correlate with increases in aggressive response demonstrating a link between AH-dopamine and the control of aggression (Ricci et al., 2009). Interestingly, the increases in dopamine were localized to two distinct nuclei within the anterior hypothalamus, the nucleus circularis (NC) and the medial supraoptic nucleus (mSON). The NC and mSON innervate a lateral subdivision of the anterior hypothalamus (LAH) suggesting that AAS-induced increases in dopamine within these nuclei alter the aggressive response through modulation of LAH activity. In fact, dopamine receptor expression in the AH appears to be localized to this lateral subregion (i.e. the LAH) (Ricci et al., 2009; Schwartzer, Ricci, & Melloni, 2009b) indicating that dopamine from the NC and mSON modulate AH activity through local innervation to LAH neurons. Taken together, these previous reports suggest a link between the dopamine neural system and the control of AAS-induced aggression.

Dopamine receptors are classified into two families, D1-like receptors (D1, D5) and D2-like receptors (D2, D3, D4) (Sibley, Monsma, & Shen, 1993). While both receptor types are G-protein coupled, activation of D1-like and D2-like receptors produce opposing responses (Bunzow et al., 1988; Monsma, Mahan, McVittie, Gerfen, & Sibley, 1990; Sibley et al., 1993). Specifically, D2-like receptors are negatively linked to adenylyl cyclase such that activation of these receptors results in neuronal inhibition (Bunzow et al., 1988). Conversely, D1-like receptor activation increases adenylyl cyclase producing increased neuronal activity and excitation (Monsma et al., 1990). Both D2-like and D1-like receptors, particularly D2 and D5, are implicated in aggression control in various species and animal models, and localize to the AH (Bondar & Kudryavtseva, 2005; Nikulina & Kapralova, 1992; Rodriguez-Arias, Minarro, Aguilar, Pinazo, & Simon, 1998; Tidey & Miczek, 1992). For example, blockade of D2 receptors using haloperidol and risperidone in preclinical models has demonstrated efficacy for reducing aggression in mice (Miczek, Fish, De Bold, & De Almeida, 2002) and hamsters (L. A. Ricci, D. F. Connor, R. Morrison, & R. H. Melloni, 2007; Schwartzer, Connor, Morrison, Ricci, & Melloni, 2008). Moreover in clinical settings, antagonism of D2 receptors using antipsychotic medication has indication for the control of aggression (Findling et al., 2000; Findling, Steiner, & Weller, 2005; Schur et al., 2003). However, the effectiveness of these drugs for aggression reduction is accompanied by decreases in arousal and motor control (Jerrell, Hwang, & Livingston, 2008). Similarly, systemic administration of selective D1-like receptor antagonists reduce aggression with concomitant alterations in motor behavior (Arregui, Azpiroz, Brain, & Simon, 1993; Bondar & Kudryavtseva, 2005; Gendreau, Gariepy, Petitto, & Lewis, 1997; Miczek, Weerts, Haney, & Tidey, 1994; Nikulina & Kapralova, 1992; Rodriguez-Arias et al., 1998). For example, in the instance of morphine withdrawal, administration of the selective D1/D5 antagonist SCH-23390 significantly reduced the number of aggressive acts while decreasing mobility in mice (Rodriguez-Arias, Pinazo, Minarro, & Stinus, 1999). Additionally, in isolation induced-aggression, similar reductions in aggression and locomotor activity were reported after antagonism of D1-like receptors (Arregui et al., 1993). While these reports demonstrate a role for D2 and D5 receptors in aggression, there is little research to date investigating the link between these receptors and AAS-induced aggression. Interestingly, while several reports have shown that D2 receptor mRNA is androgen sensitive and altered in various brain regions after exposure to AAS (Birgner et al., 2008; Kindlundh, Lindblom, & Nyberg, 2003) less is known about the sensitivity of D5 receptors to androgen levels. Considering (1) that pharmacology targeting D2 and D5 receptors alters aggression in various species and paradigms, (2) the high level of distribution of D5 and D2 receptors in the hypothalamus (Meador-Woodruff, 1994; Meador-Woodruff et al., 1989; Zhou, Apostolakis, & O'Malley, 1999), and (3) the potential sensitivity of these receptors to AAS, it is hypothesized that increased dopamine innervation to the AH after adolescent AAS exposure activates D2 and D5 receptors facilitating the development of the elevated aggressive phenotype. However, the high incidence of extrapyramidal effects associated with the pharmacology used to target these receptors complicates the question of whether drugs targeting D2 and D5 receptors are specific to aggression or whether they exert their anti-aggressive effects through nonspecific mechanisms, such as changes in mobility. To resolve this discrepancy, the current studies utilized microinjection techniques to determine whether local antagonism of D2 or D5 receptors in the AH suppresses adolescent AAS-induced aggression in the absence of changes in motor activity.

Examination of hypothalamic dopamine and the expression of dopaminergic receptors in the AH has led to a less than complete understanding of the potential mechanisms whereby dopamine alters aggression. One plausible mechanism has examined the interactions between dopamine and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) functions within the AH. Both GABA and dopamine neural systems are present in the AH and undergo alterations after repeated exposure to AAS (Grimes, Ricci, & Melloni, 2003; Ricci et al., 2009). Furthermore, inhibitory D2 receptors are localized to the LAH and increase as a result of adolescent treatment with AAS (Ricci et al., 2009). Dopamine neurons often synapse on medium-spiny GABAergic neurons (Guzman et al., 2003; Pickel, Nirenberg, & Milner, 1996), and these GABAergic interneurons commonly express inhibitory D2-like and excitatory D1-like receptors across various brain regions (Gerfen et al., 1990; Santana, Mengod, & Artigas, 2008). Recent research has identified a population of neurons expressing glutamic acid decarboxylase-67 (GAD67; a biosynthetic marker for GABA synthesis) in the LAH labeled with D2 receptors (Schwartzer et al., 2009b). Interestingly, while adolescent AAS exposure increases the number of neurons synthesizing GABA (i.e. GAD67) in the LAH, the number of D2 containing GAD67 neurons remains unaltered. These findings demonstrate the existence of a second population of GABAergic neurons (i.e. non D2-positive) in the AH (Schwartzer et al., 2009b). Identifying this secondary system would resolve previously conflicting reports regarding the excitatory and inhibitory role of GABA in the control of aggression (Depaulis & Vergnes, 1985; Liu et al., 2007; Miczek et al., 2002). It is hypothesized that this secondary GABAergic system in the LAH expresses excitatory D5 receptors such that increases in hypothalamic dopamine both activate and inhibit differential populations of GABA neurons. To explore this potential mechanism and determine if these cells are altered by the presence of AAS throughout adolescent development, we utilized double immunofluorescence to colocalize D5 receptors with GAD67 containing neurons in the LAH.

Methods

Animals

Male Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) (N = 108) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) individually housed in polycarbonate cages, and maintained at ambient room temperature (22-24°C, with 55% relative humidity) on a reverse light-dark cycle (14L:10D; lights off at 08:00) as previously described (Grimes & Melloni, 2002). Food and water were provided ad libitum. For aggression testing, stimulus (intruder) males of equal size and weight to the experimental animals were obtained from Charles River Laboratories one week prior to the behavioral test, group-housed (five animals per cage) in large polycarbonate cages, and maintained as above to acclimate to the animal facility. All studies employing live animals were pre-approved by the Northeastern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and all methods used were consistent with guidelines provided by the National Institutes of Health for the scientific treatment of animals.

Drugs

Testosterone cypionate, nandrolone decanoate, and boldenone undecylenate were purchased from Steraloids Inc. (Newport, RI) and prepared in sesame oil. S(-)-Eticlopride hydrochloride and SCH-23390 were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in 0.9% (wt/vol) normal saline.

Experimental Treatment

Postnatal day (P) 27 hamsters (n = 102) received daily subcutaneous (SC) injections (0.1-0.2 ml) of an AAS mixture consisting of 2 mg/kg testosterone cypionate, 2 mg/kg nandrolone decanoate, and 1 mg/kg boldenone undecylenate dissolved in sesame oil, for 30 consecutive days during adolescent development (P27-P56). This treatment regimen, designed to mimic a chronic use regimen (H. G. Pope, Jr. & Katz, 1994; H. G. Pope, Katz, D.L., Champoux, R., 1988), has been shown repeatedly to produce highly aggressive animals in greater than 85% of the treatment pool (DeLeon, Grimes, & Melloni, 2002; Grimes & Melloni, 2005). As a non-aggressive control, a separate set of animals received SC injections of sesame oil alone (n = 6).

Surgical Procedure

One week prior to aggression testing (P50), animals (n = 96) were anesthetized with isoflurane (1-4%, inhalation) and placed into a stereotaxic device for unilateral implantation of a 26 gauge guide cannula aimed at the AH. An incision was made to expose the dorsal surface of the skull. The skull surface was then wiped clean to reveal the position of lambda and bregma landmarks. A small hole was drilled into the skull at the coordinate position necessary to gain access to the anterior hypothalamus, specifically directed to the lateral subdivision (i.e., 0.7mm anterior to bregma, 0.6mm lateral to the midsagittal suture, 6.8mm ventral from dura). The cannula was placed in the brain angled at 8 degrees and anchored to the skull using dental screws and acrylic. The head-wound was then sutured closed and topical antibiotic ointment applied to the wound area. To verify cannula placement, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane one day following behavioral testing and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed, postfixed for 90 minutes in perfusion fixative, and cryoprotected overnight in 30% sucrose at 4°C. Brains were cut at 40μm on a freezing microtome in serial, coronal section and mounted on gelatin-coated slides. Sections were stained with cresyl violet, dehydrated through a series of alcohols, cleared with xylene, and coverslipped with Cytoseal (Stephens Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Only animals with correctly placed cannula tips into the AH were included in the statistical analysis (Figure 1).

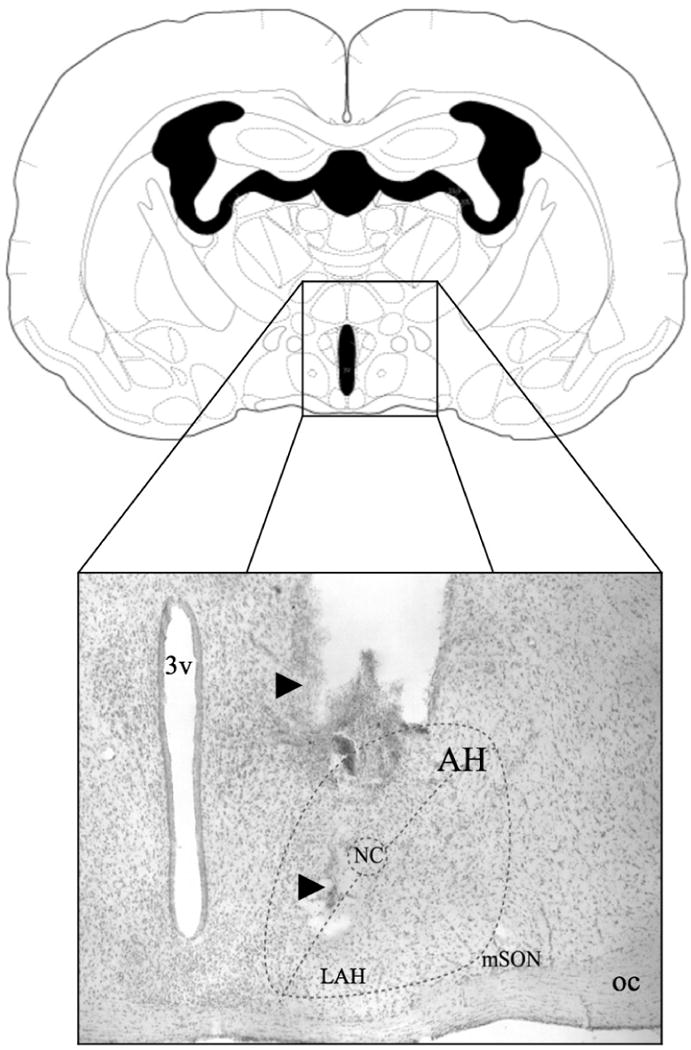

Figure 1.

Schematic (adapted from Morin & Wood, 2001) and representative photomicrograph of a coronal section of the Syrian hamster brain showing the site of central administration of eticlolpride and SCH-23390 into the anterior hypothalamus. Note in the photomicrograph (from the dorsal to ventral axis), the track of the guide-cannula and the track of the injection needle (arrows) aimed toward the lateral subdivision of the anterior hypothalamus (i.e the LAH). 3v: third ventricle; AH: anterior hypothalamus; mSON: medial supraoptic nucleus; NC: nucleus circularis; oc: optic chiasm.

Microinjections

A 2-μl Hamilton syringe was connected to a 33-gauge stainless injection needle via polyethelene tubing. Injection of drugs into the AH was performed by lowering the injection needle through the guide cannula, delivering a final volume of 0.5μl of drug over 3 minutes and left in position for an additional minute to allow for drug diffusion away from the injector tip. The internal-injector cannula protruded 1 mm beyond the guide cannula toward the LAH (Figure 1). Based on the volume selected and the diffusion rate of microinjected substances (Myers, 1966; Routtenberg, 1972), spread of drug beyond the AH of animals with correctly verified cannula placements is limited. Importantly, while it is difficult to restrict the spread of drug to the LAH and limit diffusion dorsal of the injection site (i.e. to the medial dorsal AH), the sparse distribution of dopamine receptors in the dorsal medial regions of the AH (Ricci et al., 2009; Schwartzer et al., 2009b) would suggest that receptor antagonism effects were produced in the LAH.

Behavioral Testing

After the microinjection, animals were returned to their home cage for ten minutes before undergoing behavioral testing. Hamsters were tested for offensive aggression using the resident-intruder paradigm, a well-characterized and ethologically valid model of offensive aggression in Syrian hamsters (Floody & Pfaff, 1974; Lerwill & Makings, 1971). Briefly, a novel intruder of similar size and weight was introduced into the home cage of the experimental animal (resident) and the resident was scored for specific and targeted aggressive responses including upright offensive postures, lateral attacks, and flank/rump bites, as previously described (Grimes et al., 2003; Ricci, Rasakham, Grimes, & Melloni, 2006). An attack was scored each time the resident animal would pursue and then either [1] lunge toward and/or [2] confine the intruder by upright and sideways threat; each generally followed by a direct attempt to bite the intruder's dorsal rump and/or flank target area(s). A composite aggression score, used as a general measure of offensive aggression, was defined as the total number of attacks (i.e. upright offensives and lateral attacks) and bites (i.e. flank/rump bites) during the behavioral test period. The latency to attack was defined as the period of time between the beginning of the behavioral test and the first attack the residents made toward an intruder. In the case of no attacks, latencies to attack were assigned the maximum latency (i.e., 600s). Each aggression test lasted for 10 minutes and was videotaped and scored manually by two observers unaware of the hamsters' experimental treatment. Inter-rater reliability was set at 95%. No intruder was used for more than one behavioral test, and all subjects were tested during the first 4 hours of the dark cycle under dim red illumination to control for circadian influences on behavioral responding. In addition to aggressive behaviors, residents were measured for social interest toward intruders defined as the period of time during which the resident deliberately initiated contact with the intruder (i.e. contact time between resident and intruder) and the frequency of investigatory sniffing (i.e. nose-to-nose and circle, mutual sniff [Johnston, 1985]) to control for nonspecific effects of dopamine receptor agents on behavior. To measure possible changes in motor activity due to dopamine receptor antagonism, animals were measured for changes in locomotor activity (i.e. number of line crosses) during the 10-minute agonistic encounter.

Experimental Design

For pharmacology studies, Syrian hamsters (P27) received daily SC injections of an AAS cocktail for 30 days of adolescence (P27-P56). One day following the last injection (P57), AAS-treated hamsters were randomly assigned to treatment groups (n = 12/group, 8 groups) and tested for offensive aggression following an injection of saline or one of three doses (0.01, 0.1, or 1.0μg in 0.5μl) of eticlopride (i.e. a D2 antagonist) or of SCH-23390 (i.e. a D5 receptor antagonist) into the AH. Eticlopride and SCH-23390 were selected based on their affinities for the D2 receptor [Ki = 0.09nM (Martelle & Nader, 2008; Seeman & Ulpian, 1988)] and the D5 receptor [Ki = 0.28 nM (Millan, Newman-Tancredi, Quentric, & Cussac, 2001), respectively. The dose ranges were selected based on previous effective doses in rats (Bari & Pierce, 2005; Magnusson & Fisher, 2000; Sun & Rebec, 2005).

Immunofluorescence

For histological examination of D5 receptor expression, a subset of hamsters (n = 6/group) were treated with AAS or oil and tested for aggression in the absence of intracranial cannulation. One day following behavioral testing, animals were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (80 mg/kg:12 mg/kg) and the brains fixed by transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed, post-fixed in perfusion fixative for 90 minutes, then cryoprotected by incubation in 30% sucrose in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (0.1 M PBS; 0.001 M KH2 PO4, 0.01 M Na2 HPO4, 0.137 M NaCl, 0.003 M KCl, pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C. Consecutive series of 35μm coronal sections were cut using a freezing microtome and collected as free-floating sections in PBS. Sections were rinsed three times for 10 minutes each in 0.1 M PBS followed by preincubation in antibody buffer containing 2% normal donkey serum in 0.1 M PBS for 60 minutes. Primary antibodies (GAD67, polyclonal, Santa Cruz; Santa Cruz, CA; D5 [D1b], polyclonal, Genway Biotech; San Diego, CA) were diluted to 1:500 and left overnight on a rotating wheel at 4°C. Sections were washed three times for 10 minutes each, incubated in secondary Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated donkey anti-goat and Alexa Fluor 568 conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 60 minutes at a concentration of 1:200. Slides were coverslipped using fluoromount G (Southern biotechnology, Birmingham, Alabama) and imaged for quantitative analysis.

Image Analysis

Double-label immunofluorescence of D5 receptors and GAD67 was quantified using the BIOQUANT NOVA 5.8 computer assisted microscopic image analysis software package. BIOQUANT NOVA 5.8 analysis software running on a Pentium III CSI Open PC computer (R&M Biometrics, Nashville, TN, USA) was utilized to identify the LAH. A standard computer generated parcel was drawn to outline the entire brain region of interest at lower power (4×) using the darkfield settings on an Olympus BX51 microscope fitted with X-cite series 120 mercury lamp unit and Texas Red/FITC interference filters. For immunofluorescence, two images of each tissue section from the LAH were captured, one for each filter set (i.e. Texas Red and FITC), and images were overlaid for double-label analysis. For each of the three images, all positively stained cells were identified and counted using a mouse-driven cursor for quantification. Manual measurements continued at 20× until all cells were counted throughout the LAH. Four to six independent measures were taken from several consecutive sections (2–4) for each animal. All cell counts in the LAH were averaged between hemispheres and used for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

To measure the extent to which AAS-exposure elevated aggressive responding, composite aggression scores of AAS and sesame oil-treated animals used for immunohistochemistry were compared using Student's t-test. Additionally, to determine whether stereotaxic surgery altered aggression responding compared to surgically naïve controls, AAS-treated animals injected with saline on test day were collapsed across experiments and compared to surgically naïve AAS-treated hamsters using Student's t-test. For microinjection studies, behavioral measures were compared between treatment groups using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's protected least significant difference post hoc test (two-tailed) when applicable. Composite Aggression scores of animals with cannulas placed outside the AH were compared to AAS-treated hamsters injected with saline using one-way ANOVA. Immunofluorescence data was compared between AAS and sesame oil-treated controls using a priori planned comparison Student's t-test. Finally, to determine whether changes in expression of D5- and/or GAD67 correlates with aggression intensity, the number of fluorescently labeled D5 and GAD67 cell bodies was correlated with composite aggression scores using Pearson's r correlation coefficient. The alpha level was set at 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

AAS-induced Aggression

As previously reported (Melloni & Ricci, 2009) hamsters exposed to AAS throughout adolescent development displayed significantly increased frequency of aggressive behaviors compared to sesame oil-treated littermates [t(10) = 2.33, p < 0.05]. These aggressive AAS-treated animals displayed a greater than 5-fold increase in the total number of aggressive acts (i.e. composite aggression score) compared to oil-treated controls (AAS: mean = 10.5; Sesame oil: mean = 1.8). Conversely, the frequency of aggressive displays of AAS-treated animals infused with saline into the AH was no different to that of surgically naïve AAS-treated controls [t(25) = 1.30, p < 0.05].

SCH-23390

There were twenty-six animals with correctly placed AH cannula included in the final analysis (0.0μg: n = 9; 0.01μg: n = 5; 0.1μg: n = 6; 1.0μg: n = 6) (Figure 1). Those animals treated with SCH-23390 outside the AH showed no statistically significant difference in AAS-induced aggression, F(3, 14) = 2.3, p > 0.1, and were excluded from behavioral analysis.

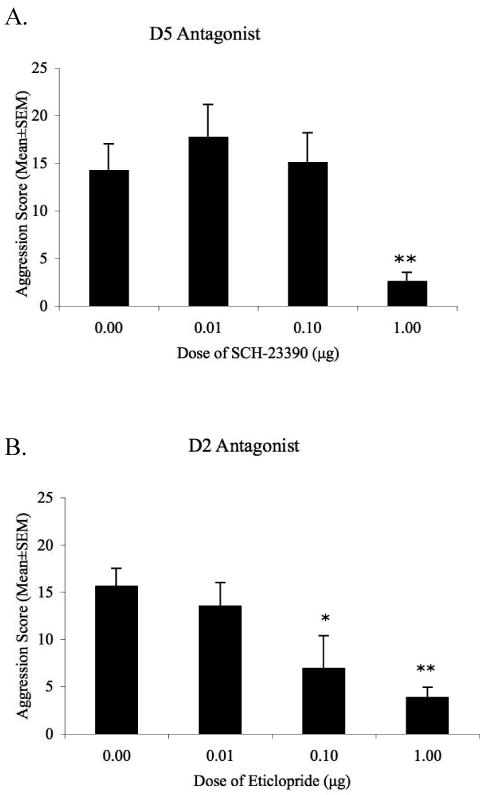

Local infusion of the D5 receptor antagonist SCH-23390 into the AH produced an overall decrease in offensive aggression as measured by composite aggression score, F(3, 22) = 5.48, p < 0.01. Post hoc analysis revealed that both the low (0.01μg) and moderate (0.1μg) doses of SCH-23390 failed to alter aggression compared to AAS-treated animals administered saline on test day [0.01μg, t(12) = -0.89, p > 0.3; 0.1μg, t(13) = -0.23, p > 0.5]. Only the highest dose (1.0μg) of the D5 receptor antagonist reduced aggressive behavior compared to controls [t(13) = 3.19, p < 0.01]. At this high dose, animals displayed a 4-fold reduction in aggression compared to AAS-treated animals administered saline into the AH (Figure 2). Treatment with SCH-23390 also produced a significant increase in the latency to first attack, F(3, 22) = 4.53, p < 0.05. These increases in attack latency occurred when AAS-treated animals were injected with the highest dose [1.0μg: t(13) = 3.08, p < 0.01] but not the moderate or low doses, [0.01μg, t(12) = 0.45, p > 0.6; 0.1μg, t(13) = 0.26, p > 0.7;] of the D5 receptor antagonist when compared to AAS-treated animals injected with saline. Interestingly, these reductions in aggression occurred with concomitant alterations to locomotion and social interest. Indeed, local administration of the D5 receptor antagonist produced a significant main effect on the number of line crosses, F(3, 20) = 3.10, p < 0.05. While the low and moderate doses of SCH-23390 had no effect on locomotor activity, [0.01μg, t(12) = -1.37, p > 0.1; 0.1μg, t(13) = 0.21, p > 0.5], the aggression suppressing high dose resulted in a significant decrease in line crosses [t(13) = 2.11, p < 0.05]. In fact, hamsters treated with 1.0μg of SCH-23390 made fewer than half as many line crosses when compared to saline-treated AAS controls (Table 1). Similarly, AH injection of the D5 receptor antagonist altered social interest with a significant main effect observed in the total contact time spent between resident and intruder, F(3, 20) = 4.37, p < 0.05. Animals administered the highest dose of SCH-23390 spent significantly less time interacting with the intruder during the 10-minute period [t(13) = 3.06, p < 0.01], while the moderate and low doses had no effect on total contact time [0.01μg, t(12) = -0.6, p > 0.5; 0.1μg, t(13) = 0.1, p > 0.5]. Finally no differences were observed in the frequency of investigatory sniffing behavior across all treatment groups, F(3, 20) = 2.51, p > 0.05.

Figure 2.

Composite aggression score of AAS-treated animals after injection of the D2 receptor antagonist eticlopride or the D5 receptor antagonist SCH-23390 (0.1μg -1.0μg/0.5μl) in the anterior hypothalamus. A. Only the highest dose of SCH-23390 suppressed AAS-induced aggression when compared to steroid treated animals administered saline. B. Both moderate (0.1μg) and high (1.0μg) doses of eticloprdie dose-dependently decreased AAS-induced aggression. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared to AAS-treated hamsters injected with saline into the AH on test day.

Table 1.

Effects of microinfusion of SCH-23390 or eticlopride into the AH of adolescent AAS-treated hamsters on locomotor and social interest. Data represents mean values with standard deviation.

| Behavioral Category | Dose (μg/0.5μl) | Probability associated with One-way ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 1.00 | |||

| Contact Time | D5 | 469 (73) | 497 (58) | 466 (26) | 365 (80)* | <0.05 |

| D2 | 464 (94) | 439 (96) | 480 (77) | 450 (88) | n.s. | |

| Sniffing | D5 | 22 (4.8) | 29 (2.5) | 23 (8.8) | 19 (5.6) | n.s. |

| D2 | 18 (12) | 23 (11) | 10 (5) | 11 (5) | n.s. | |

| Line Crosses | D5 | 47 (26) | 54 (13) | 45 (7) | 27 (13)** | <0.05 |

| D2 | 68 (35) | 49 (30) | 35 (25) | 42 (14) | n.s. | |

Differs from AAS-treated controls (0.0μg dose), p < 0.05

Differs from AAS-treated controls (0.0μg dose), p < 0.01

Eticlopride

Thirty-three animals with correct cannula placements in the AH were included in the behavioral analysis (0.0μg: n = 12; 0.01μg: n = 8; 0.1μg: n = 7; 1.0μg: n = 6). Some animals were injected outside the AH (0.01μg: n = 4; 0.1μg: n = 4; 1.0μg: n = 5) with cannulas placed rostral or caudal to the AH. Animals with incorrectly placed cannulas displayed no significant changes in aggressive behaviors and were excluded from the final analysis, F(3, 20) = 2.08, p > 0.1.

Injection of the D2 antagonist eticlopride into the AH produced an overall effect on offensive aggression, F(3, 29) = 4.92, p < 0.01, with an effective dose at 0.1μg. At this dose, eticlopride treatment significantly decreased composite aggression [t(17) = 2.64, p < 0.05], when compared to aggressive AAS-treated hamsters injected with saline into the AH. Specifically, infusion of eticlopride into the AH reduced the frequency of aggressive behaviors by more than half during the 10-minute period (Figure 2). Similarly, eticlopride significantly reduced composite aggression scores for the highest dose tested [1.0μg, t(16) = 3.07, p < 0.05]. However, at the lowest dose of the D2 antagonist, 0.01μg, no changes were observed in AAS-induced aggressive behaviors [t(18) = 0.66, p > 0.5]. Additionally, no differences were observed in the latency to attack the intruder across treatment groups, F(3, 29) = 1.38, p > 0.2. To assess any non-specific effects of eticlopride injections into the AH, animals were scored for social contact time, investigatory sniffing, and locomotor behaviors during the 10-minute resident-intruder test. At all doses tested, administration of eticlopride into the AH had no effect on the time residents spent in contact with the intruder [F(3, 29) = 0.28, p > 0.5], the frequency of sniffing [F(3, 29) = 2.82, p > 0.5] or in locomotor activity [line crosses; F(3, 29) = 2.44, p > 0.1] compared to AAS-treated animals administered saline into the AH (Table 1).

Double-label Immunofluorescence

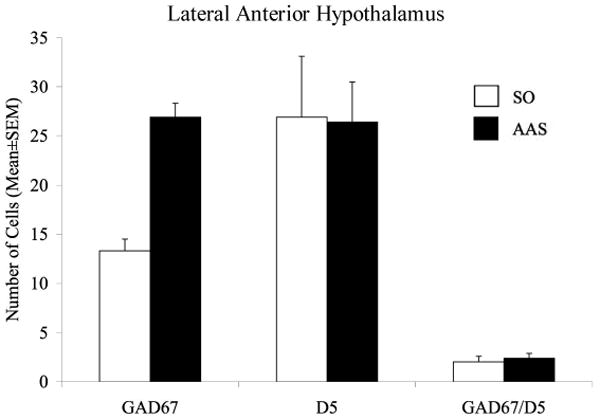

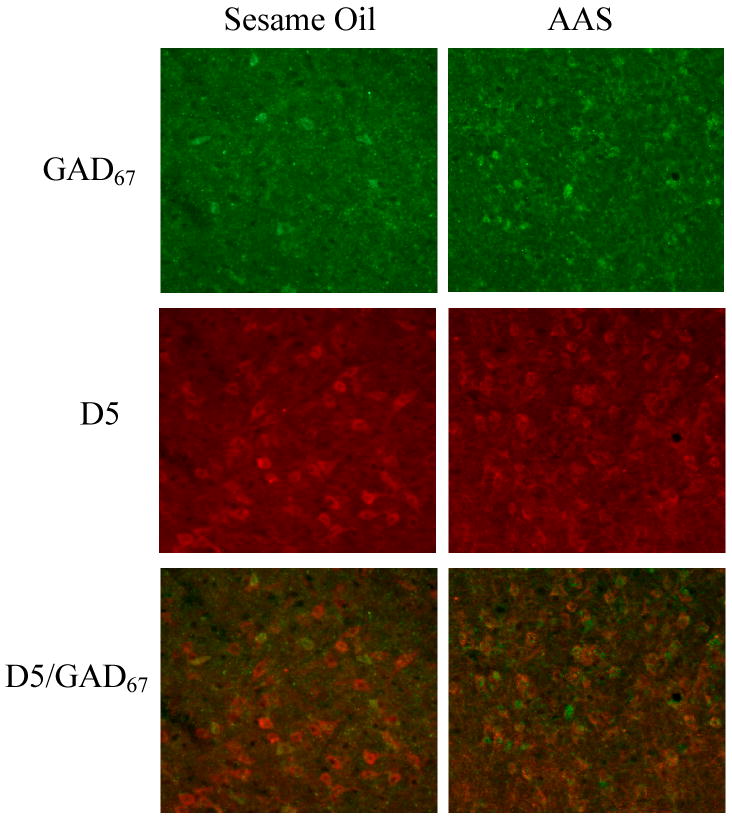

In agreement with previously published findings (Schwatzer et al, 2009), AAS-treated animals exhibited an increased number of cell bodies expressing GAD67 in the LAH compared to sesame oil-treated controls (Figure 3). This increase was statistically significant [t(10) = 2.76, p < 0.05] and correlated with increases in aggressive responding, r = 0.58, p < 0.05. In contrast, AAS treatment had no effect on the number of cells positively labeled for D5 receptors in the LAH [t(10) = 0.95, p > 0.5] (Figure 3), and no correlation was found between D5 receptor expression and aggression intensity, r = -0.02, p > 0.9. Interestingly, few cells were positively labeled for both GAD67 and D5 receptors indicating limited colocalization of these two proteins (Figure 4). This colocalized population showed no changes in the number of cells co-expressing GAD67 and D5 receptors between AAS and oil treated controls, t(10) = -0.51, p > 0.05] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Treatment with AAS throughout adolescence altered GAD67 but not D5 immunofluorescent staining in the LAH. Animals treated with AAS showed a significnat increase in the number of cells positively labeled for GAD67. However no changes were observed in the number of cells expressing D5 receptors between AAS and sesame oil-controls. Interestingly, few neurons were positively labeled with both GAD67 and D5 receptors and were unaltered by AAS-treatment. *p<0.05; Student's t-test, two-tailed (n = 6/group).

Figure 4.

Darkfield photomicrographs of a coronal section through the LAH at 20× magnification. Shown are cells positively labeled with GAD67 (green), D5 receptors (red), and double-labeled GAD67/D5 cells (overlay) of sesame oil and AAS treated hamsters.

Discussion

Previous studies investigating the role of dopamine and various dopaminergic receptors in the control of aggression have resulted in varied and contradictory findings given that many of the pharmacological agents used have limited specificity to individual dopamine receptors (Bourne, 2001; Hardman, Limbird, & Gilman, 2001). Moreover, studies using systemic drug treatments report large variation in aggression-specificity as these agents disrupt normal striatal functions producing a myriad of extrapyramidal and locomotor side effects. To control for these variables, the present studies examined the role of hypothalamic dopamine in adolescent AAS-induced aggression utilizing local infusion techniques to limit drug/receptor interactions. Our findings report that eticlopride, but not SCH-23390, selectively modulated AAS-induced aggression while leaving motor and other social behaviors unaltered. To elucidate a putative mechanism that explains the findings from our pharmacology studies, double-label fluorescent immunohistochemistry was used to investigate whether AH dopamine afferents modulate local GABAergic interneurons resulting in elevated aggression.

Dopaminergic activity in the central nervous system is critical for the control of aggression across vertebrate species (Miczek et al., 2002) as systemic increases in dopamine and non-selective activation of dopaminergic receptors facilitate aggressive behaviors (Maeda, Sato, & Maki, 1985; Sato & Wada, 1974; Sweidan, Edinger, & Siegel, 1990, 1991). In the AH, activation of dopamine receptors using the non-selective agonist apomorphine increases aggressive reactions supporting a local effect of dopamine on aggression control (Sweidan et al., 1991). The hypothalamus is densely innervated by dopaminergic projections and expresses high amount of excitatory D5 and inhibitory D2 receptors (Meador-Woodruff, 1994; Meador-Woodruff et al., 1989; Zhou et al., 1999). In the Syrian hamster, the organization and expression of the hypothalamic neural system appears to be androgen sensitive and is reported to undergo alterations after adolescent exposure to AAS (for review see Melloni & Ricci, 2009). Specifically, treatment with moderate doses of AAS throughout the developmentally sensitive period of adolescence increases both the dopaminergic innervation and the expression of D2 receptors within the AH (Ricci et al., 2009; Schwartzer et al., 2009b). This increase in the density of dopamine afferents correlates with the elevated aggressive response (Ricci et al., 2009). It is hypothesized that this increase in AH dopamine facilitates aggression through stimulation of inhibitory D2 receptors in the LAH. Evidence supporting this notion stems from our finding that local blockade of D2 receptors using the selective antagonist eticlopride dose-dependently decreased AAS-induced aggression. This decrease occurred in the absence of changes in motor activity and overall arousal in social interactions. Reductions in the frequency and intensity of aggressive responding in the absence of changes to non-aggression related behaviors indicates the specificity of D2 receptor activity in the AH to control aggression. Moreover, the aggression suppressing effects of eticlopride were ineffective when injected into nuclei rostral and caudal to the AH, further supporting the notion that this brain region, and specifically dopamine within this region, modulate AAS-induced aggression. These findings notwithstanding, there are multiple dopaminergic receptor subtypes expressed within the AH, so the finding that D2 antagonists suppress AAS-induced aggression may only be one part of a larger dopamine mechanism within the AH.

In addition to D2 receptors, the hypothalamus is densely populated with excitatory D5 receptors (Meador-Woodruff, 1994; Zhou et al., 1999). It was hypothesized that increased dopamine innervation to the LAH after adolescent AAS-exposure may also facilitate aggression by increasing hypothalamic activity through activation of D5 receptors. In previous studies, systemic antagonism of excitatory D1/D5 receptors reduced aggression across species and animal models (Arregui et al., 1993; Bondar & Kudryavtseva, 2005; Gendreau et al., 1997; Miczek et al., 1994; Nikulina & Kapralova, 1992; Rodriguez-Arias et al., 1998). However these studies were limited in clear interpretation as they produced confounded results (i.e., systemic treatment resulted in decreased aggression concomitant with alterations in mobility). Moreover, the inability of current pharmacology to selectively bind either only D1 or D5 receptors further reduces the ability to determine which dopamine receptors are specific to aggression control. Here we suggest that these possible confounds were eliminated with the use of local drug administration techniques. Given that the hypothalamus only expresses high levels of D5 and very low levels of D1, local infusion of the D1/D5 antagonist SCH-23390 site specifically targeted D5 receptors while leaving striatal D1 receptors unaltered (Palermo-Neto, 1997). Interestingly, only the highest dose of SCH-23390 tested suppressed AAS-induced aggression. At this high dose, animals displayed significantly decreased locomotor activity, as measured by the number of line crosses in a 10-minute period, and reductions in the total time spent interacting with a novel intruder. Therefore, the observed reductions in AAS-induced aggressive behavior are more likely explained by non-specific drug effects and suggest that LAH-D5 receptors do not directly modulate AAS-induced aggression. The AH is involved in mediating various hormonal and behavioral responses including thermoregulation, sexual behavior, and neuroendocrine function (Cox & Lee, 1977; Hull et al., 1986; MacKenzie, Hunter, Daly, & Wilson, 1984). Thus, a reduction in aggression after local D5 receptor blockade may reflect a decrease in overall arousal brought about by disruption to other hypothalamic-mediated processes.

Taking together the findings from pharmacological manipulations of AH D2 and D5 receptors, it is hypothesized that D2, but not D5 receptors, modulate AAS-induced aggression. That is, adolescent exposure to AAS increases dopaminergic tone within the AH resulting in increased activation of D2 receptors. This notion is consistent with previous reports investigating hypothalamic control of aggression in felines. Increased aggressive reaction elicited by infusion of apomorphine into the AH can be suppressed by local injection of sulpride, a D2 specific antagonist, but not SCH-23390 (Sweidan et al., 1991). Similarly, cats showed increased aggression when D2, but not D5, receptors were activated by AH administration of selective agonists (Sweidan et al., 1991). While these reports and the findings from our pharmacology studies would suggest that AH D5 receptors are not implicated in the regulation of AAS-induced aggression, it is possible that their function may still be important, albeit difficult to discern. For this reason, it is important to consider the neuroanatomical localization of D2 and D5 receptors within the AH and how they may be altered in adolescent AAS-treated animals to more completely implicate or eliminate these receptors in the control of steroid-induced aggression.

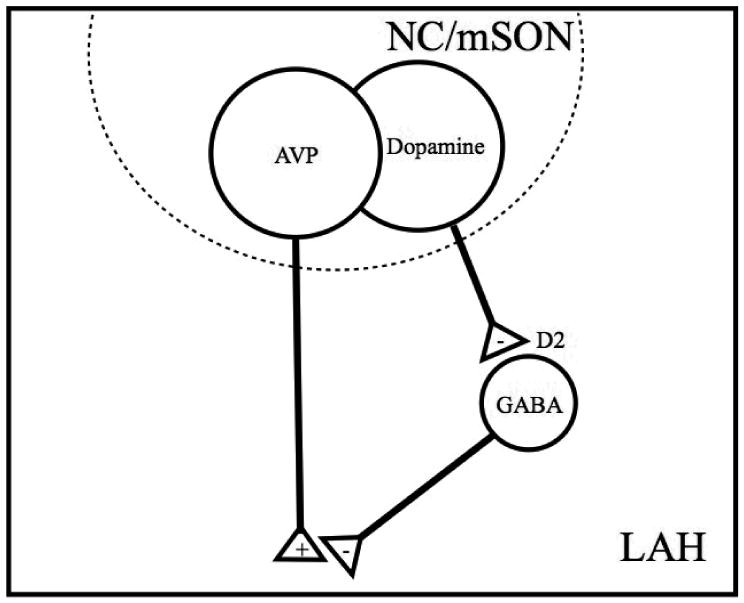

In the Syrian hamster, aggression is modulated, in part, by the interaction between excitatory arginine vasopressin (AVP) and inhibitory serotonin (5HT) (Ferris et al., 1997). When exposed to AAS throughout adolescence, AVP tone is increased and 5HT afferents are diminished producing the elevated aggressive response (Melloni & Ricci, 2009). While dopaminergic innervation to the LAH is postulated to modulate both AVP and 5HT release (Melloni & Ricci, 2009; Schwartzer et al., 2009b), the exact mechanisms remain unknown. One putative mechanism for the role of dopamine is through its differential modulation of GABAergic interneurons. The AH, specifically the LAH, is densely populated with GABAergic neurons and inhibitory GABAA receptors, both of which are altered in the presence of AAS (Schwartzer et al., 2009b). Previous research reports that a subpopulation of these GABA neurons express D2 receptors but remain unaltered after adolescent AAS treatment (Schwartzer et al., 2009b). Thus it is likely that a second GABAergic system, (i.e. a non-D2 containing population) increases in the LAH to produce the elevated aggressive response. It was hypothesized that this second population of GABA neurons express excitatory D5 receptors and also modulate AAS-induced aggression. In this model, AH dopamine release modulates both excitation (i.e. D5) and inhibition (i.e. D2) of discrete GABA populations allowing for differential regulation of inhibitory (i.e. 5HT) and excitatory (i.e. AVP) inputs, respectively. Indeed, activation of GABAA receptors and increased levels of extracellular GABA produce both inhibitory and excitatory effects on aggression (Depaulis & Vergnes, 1985; Liu et al., 2007; Miczek et al., 2002), demonstrating a dual role for GABA. More specifically, dopamine activation of D2 receptors would disinhibit AH activity by suppressing GABA release onto aggression stimulating AVP while activation of D5 receptors would increase GABA inhibition of inhibitory 5HT afferents. If this model were correct, then pharmacological manipulation of AH D5 receptors would likely not effect aggressive behavior given that the development of the 5HT system is attenuated in AAS treated animals, rendering the system non-functional in suppressing the release of AVP (Melloni & Ricci, 2009). Thus, the findings in the current report that local administration of the D5 receptor antagonist SCH-23390 failed to suppress AAS-induced aggression may be indicative of a weakened neural pathway that cannot be restored. To determine whether these LAH GABAergic neurons express D5 receptors, brains from AAS and sesame oil-treated controls were processed for double-label immunofluorescence.

Consistent with previously published results, adolescent exposure to AAS resulted in a significant increase in the number of GABAergic neurons in the LAH (Schwartzer et al., 2009b). However, no changes were reported in the number of cells expressing D5 receptors. Moreover, analysis of the number of colocalized GABA neurons expressing D5 receptors produced results inconsistent with our hypothesis. In fact, few neurons were colocalized with both GAD67 and D5 receptors indicating that LAH GABA neurons rarely express D5 receptors. While this evidence in conjunction with our pharmacology studies would suggest that D5 receptors in the LAH are modulating non-GABAergic neurons that regulate hypothalamic processes indirect to aggression control, we cannot conclude that D5 receptors are altogether unaffected by adolescent AAS exposure. Evidence from studies examining gene expression of dopamine receptors after AAS-exposure would suggest that the number of receptors is unaltered given that only D1, D2 and D4, but not D3 or D5 receptor mRNA are sensitive to circulating androgens (Birgner et al., 2008; Kindlundh et al., 2003). Nevertheless, more sensitive protein assays are necessary to better explore whether D5 receptors in the LAH are steroid sensitive and undergo alterations in expression after AAS exposure throughout adolescent development. Moreover, given that D5 receptors are not expressed on LAH GABA neurons, additional histological and pharmacological studies are necessary to identify what other neural systems regulate the non-D2 expressing GABA population in order to elucidate a more complete understanding of the neural circuit within this key aggression locus. One postulated mechanism modulating this secondary GABA population is through excitatory serotonin type-2A (5-HT2A) receptors. Activation of 5-HT2A receptors increases aggressive responding while antagonism suppresses aggression in various species and animal models (L. A. Ricci, D. F. Connor, R. Morrison, & R. H. Melloni, Jr., 2007; Sakaue et al., 2002; White, Kucharik, & Moyer, 1991). Recently, 5-HT2A receptors have been localized to cell bodies in the LAH and are reported to increase after adolescent exposure to AAS (Schwartzer, Ricci, & Melloni, 2009a). Therefore, serotonin may modulate LAH activity through excitatory 5-HT2A receptors expressed on GABAergic interneurons. The existence of this speculative 5-HT2A and GABA interaction in the LAH and whether these systems work to autoregulate serotonin release must be further investigated to better understand the effects of adolescent AAS exposure on the generation of offensive aggression.

In summary, results from our pharmacology studies, immunohistochemical analysis of dopamine receptor populations in the current study, and previous reports (Schwartzer et al., 2009b), indicate that dopamine D2 receptors in the LAH directly modulate adolescent AAS-induced aggression while the role of D5 receptors most likely influence AAS-induced aggression indirectly. Additionally, we report that these receptor pools exist on two discrete neuronal populations such that AH dopamine release regulates both GABAergic neurons through inhibitory D2 receptors and non-GABAergic cell populations expressing excitatory D5 receptors. Interestingly, the D5 staining pattern observed in the present studies appears similar to the localization patterns of glutamate neurons within the LAH (Fischer, Ricci, & Melloni, 2007). In fact, dopamine modulates glutamatergic neurons across the neuraxis (Seamans, Durstewitz, Christie, Stevens, & Sejnowski, 2001; Seamans & Yang, 2004) and D5 receptors have been colocalized with glutamatergic neurons in the LAH (Schwartzer & Melloni, unpublished data). This possibility notwithstanding, AAS-induced increases in hypothalamic dopamine likely impart their aggression stimulating effects through disinhibiting AH activity. A central hypothesis currently under investigation in our laboratory is that this disinhibition occurs via increasing activation of aggression stimulating magnocellular AVP neurons. Given that 40% of synapses to magnocellular neurons are GABAergic (Gies & Theodosis, 1994), we speculate that AAS-induced increases in D2 activation in the LAH inhibits GABA mediated inhibition of magnocellular AVP resulting in elevated aggression responding (Figure 5). This hypothesis is supported by reports that D2, but not D5, receptor activation depolarize supraoptic magnocellular neurons in the hypothalamus (Yang, Bourque, & Renaud, 1991). Finally, our findings warrant a narrowed approach to investigating dopamine-mediated control of AAS-induced aggression by directing a more focused understanding of hypothalamic D2 activity with less emphasis on D5 receptor function.

Figure 5.

A model showing the hypothetical modulation of magnocellular AVP release through dopamine and GABA interactions. AAS-induced increases in dopamine from the NC and mSON activate inhibitory D2 receptors expressed on GABAergic neurons in the LAH. These local D2-expressing GABAergic neurons are hypothesized to modulate the release of aggression stimulating AVP. Therefore, AAS-induced increases in dopamine would remove GABAergic inhibition of AVP resulting in increased LAH activity and elevated aggression. (+) excitation; (-) inhibition.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend a special thanks to Dr. Lesley Ricci for her thoughtful insight, critical analysis, and technical training necessary to conduct this research. The authors would also like to thank Lauren Reynolds for her technical support in the completion of the experimental procedures. This work was supported by research grant (R01) DA10547 from NIDA to R.H.M. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIDA.

Funding Source: NIH R01-DA10547 to R.H.M.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/bne

References

- Arregui A, Azpiroz A, Brain PF, Simon V. Effects of two selective dopaminergic antagonists on ethologically-assessed encounters in male mice. Gen Pharmacol. 1993;24(2):353–356. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(93)90316-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari AA, Pierce RC. D1-like and D2 dopamine receptor antagonists administered into the shell subregion of the rat nucleus accumbens decrease cocaine, but not food, reinforcement. Neuroscience. 2005;135(3):959–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgner C, Kindlundh-Hogberg AM, Alsio J, Lindblom J, Schioth HB, Bergstrom L. The anabolic androgenic steroid nandrolone decanoate affects mRNA expression of dopaminergic but not serotonergic receptors. Brain Res. 2008;1240:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondar NP, Kudryavtseva NN. The effects of the D1 receptor antagonist SCH-23390 on individual and aggressive behavior in male mice with different experience of aggression. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2005;35(2):221–227. doi: 10.1007/s11055-005-0017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne JA. SCH 23390: the first selective dopamine D1-like receptor antagonist. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7(4):399–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley WE, Yesalis CE, 3rd, Friedl KE, Anderson WA, Streit AL, Wright JE. Estimated prevalence of anabolic steroid use among male high school seniors. JAMA. 1988;260(23):3441–3445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunzow JR, Van Tol HH, Grandy DK, Albert P, Salon J, Christie M, Machida CA, Neve KA, Civelli O. Cloning and expression of a rat D2 dopamine receptor cDNA. Nature. 1988;336(6201):783–787. doi: 10.1038/336783a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Grosz D, Saenger P, Chandler DW, Nandi R, Earls FJ. Testosterone and aggression in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(6):1217–1222. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199311000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox B, Lee TF. Do central dopamine receptors have a physiological role in thermoregulation? Br J Pharmacol. 1977;61(1):83–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1977.tb09742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbs JM, Jr, Frady RL, Carr TS, Besch NF. Saliva testosterone and criminal violence in young adult prison inmates. Psychosom Med. 1987;49(2):174–182. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198703000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbs JM, Jr, Jurkovic GJ, Frady RL. Salivary testosterone and cortisol among late adolescent male offenders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1991;19(4):469–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00919089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon KR, Grimes JM, Melloni RH., Jr Repeated anabolic-androgenic steroid treatment during adolescence increases vasopressin V(1A) receptor binding in Syrian hamsters: correlation with offensive aggression. Horm Behav. 2002;42(2):182–191. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delville Y, De Vries GJ, Ferris CF. Neural connections of the anterior hypothalamus and agonistic behavior in golden hamsters. Brain Behav Evol. 2000;55(2):53–76. doi: 10.1159/000006642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depaulis A, Vergnes M. Elicitation of conspecific attack or defense in the male rat by intraventricular injection of a GABA agonist or antagonist. Physiol Behav. 1985;35(3):447–453. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris CF, Melloni RH, Jr, Koppel G, Perry KW, Fuller RW, Delville Y. Vasopressin/serotonin interactions in the anterior hypothalamus control aggressive behavior in golden hamsters. J Neurosci. 1997;17(11):4331–4340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04331.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL, McNamara NK, Branicky LA, Schluchter MD, Lemon E, Blumer JL. A double-blind pilot study of risperidone in the treatment of conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(4):509–516. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL, Steiner H, Weller EB. Use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SG, Ricci LA, Melloni RH., Jr Repeated anabolic/androgenic steroid exposure during adolescence alters phosphate-activated glutaminase and glutamate receptor 1 (GluR1) subunit immunoreactivity in Hamster brain: correlation with offensive aggression. Behav Brain Res. 2007;180(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floody OR, Pfaff DW. Steroid hormones and aggressive behavior: approaches to the study of hormone-sensitive brain mechanisms for behavior. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1974;52(3):149–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendreau PL, Gariepy JL, Petitto JM, Lewis MH. D1 dopamine receptor mediation of social and nonsocial emotional reactivity in mice: effects of housing and strain difference in motor activity. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111(2):424–434. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Engber TM, Mahan LC, Susel Z, Chase TN, Monsma FJ, Jr, Sibley DR. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-regulated gene expression of striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons. Science. 1990;250(4986):1429–1432. doi: 10.1126/science.2147780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gies U, Theodosis DT. Synaptic plasticity in the rat supraoptic nucleus during lactation involves GABA innervation and oxytocin neurons: a quantitative immunocytochemical analysis. J Neurosci. 1994;14(5 Pt 1):2861–2869. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02861.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes JM, Melloni RH. Serotonin 1B receptor activity and expression modulate the aggression-stimulating effects of adolescent anabolic steroid exposure in hamsters. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119(5):1184–1194. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.5.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes JM, Melloni RH., Jr Serotonin modulates offensive attack in adolescent anabolic steroid-treated hamsters. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73(3):713–721. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00880-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes JM, Ricci LA, Melloni RH., Jr Glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD65) immunoreactivity in brains of aggressive, adolescent anabolic steroid-treated hamsters. Horm Behav. 2003;44(3):271–280. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman JN, Hernandez A, Galarraga E, Tapia D, Laville A, Vergara R, Aceves J, Bargas J. Dopaminergic modulation of axon collaterals interconnecting spiny neurons of the rat striatum. J Neurosci. 2003;23(26):8931–8940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-26-08931.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Gilman AG. Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 10th. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hull EM, Bitran D, Pehek EA, Warner RK, Band LC, Holmes GM. Dopaminergic control of male sex behavior in rats: effects of an intracerebrally-infused agonist. Brain Res. 1986;370(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerrell JM, Hwang TL, Livingston TS. Neurological adverse events associated with antipsychotic treatment in children and adolescents. J Child Neurol. 2008;23(12):1392–1399. doi: 10.1177/0883073808319070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RE. Social Behaviors: Communication. In: Siegel HI, editor. The Hamster: Reproduction and Behavior. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kindlundh AM, Lindblom J, Nyberg F. Chronic administration with nandrolone decanoate induces alterations in the gene-transcript content of dopamine D(1)- and D(2)-receptors in the rat brain. Brain Res. 2003;979(1-2):37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02843-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerwill CJ, Makings P. The agonistic behavior of the golden hamster. Animal Behavior. 1971;19:714–721. [Google Scholar]

- Liu GX, Liu S, Cai GQ, Sheng ZJ, Cai YQ, Jiang J, Sun X, Ma SK, Wang L, Wang ZG, Fei J. Reduced aggression in mice lacking GABA transporter subtype 1. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85(3):649–655. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie FJ, Hunter AJ, Daly C, Wilson CA. Evidence that the dopaminergic incerto-hypothalamic tract has a stimulatory effect on ovulation and gonadotrophin release. Neuroendocrinology. 1984;39(4):289–295. doi: 10.1159/000123995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H, Sato T, Maki S. Effects of dopamine agonists on hypothalamic defensive attack in cats. Physiol Behav. 1985;35(1):89–92. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson JE, Fisher K. The involvement of dopamine in nociception: the role of D(1) and D(2) receptors in the dorsolateral striatum. Brain Res. 2000;855(2):260–266. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02396-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelle JL, Nader MA. A review of the discovery, pharmacological characterization, and behavioral effects of the dopamine D2-like receptor antagonist eticlopride. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(3):248–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson A, Schalling D, Olweus D, Low H, Svensson J. Plasma testosterone, aggressive behavior, and personality dimensions in young male delinquents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1980;19:476–490. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff JH. Update on dopamine receptors. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1994;6(2):79–90. doi: 10.3109/10401239409148986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff JH, Mansour A, Bunzow JR, Van Tol HH, Watson SJ, Jr, Civelli O. Distribution of D2 dopamine receptor mRNA in rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(19):7625–7628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melloni RH, Jr, Connor DF, Hang PT, Harrison RJ, Ferris CF. Anabolic-androgenic steroid exposure during adolescence and aggressive behavior in golden hamsters. Physiol Behav. 1997;61(3):359–364. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melloni RH, Jr, Ricci LA. Adolescent exposure to anabolic/androgenic steroids and the neurobiology of offensive aggression: A hypothalamic neural model based on findings in pubertal Syrian hamsters. Horm Behav. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Fish EW, De Bold JF, De Almeida RM. Social and neural determinants of aggressive behavior: pharmacotherapeutic targets at serotonin, dopamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid systems. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163(3-4):434–458. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Weerts E, Haney M, Tidey J. Neurobiological mechanisms controlling aggression: preclinical developments for pharmacotherapeutic interventions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1994;18(1):97–110. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Newman-Tancredi A, Quentric Y, Cussac D. The “selective” dopamine D1 receptor antagonist, SCH23390, is a potent and high efficacy agonist at cloned human serotonin2C receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156(1):58–62. doi: 10.1007/s002130100742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsma FJ, Jr, Mahan LC, McVittie LD, Gerfen CR, Sibley DR. Molecular cloning and expression of a D1 dopamine receptor linked to adenylyl cyclase activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(17):6723–6727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin LP, Wood RI. A Stereotaxic Atlas of The Golden Hamster Brain. Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Myers RD. Injection of solutions into cerebral tissue: relation between volume and diffusion. Physiol Behav. 1966;1:171–174. [Google Scholar]

- NIDACapsules. 2008 http//www.nida.nih.gov/NIDACapsules/NCIndex.html.

- Nikulina EM, Kapralova NS. Role of dopamine receptors in the regulation of aggression in mice; relationship to genotype. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 1992;22(5):364–369. doi: 10.1007/BF01186627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo-Neto J. Dopaminergic systems. Dopamine receptors. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1997;20(4):705–721. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickel VM, Nirenberg MJ, Milner TA. Ultrastructural view of central catecholaminergic transmission: immunocytochemical localization of synthesizing enzymes, transporters and receptors. J Neurocytol. 1996;25(12):843–856. doi: 10.1007/BF02284846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Katz DL. Psychiatric and medical effects of anabolic-androgenic steroid use. A controlled study of 160 athletes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(5):375–382. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950050035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Katz DL, Champoux R. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use among 1010 college men. Physician Sports Med. 1988;16:75–81. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1988.11709554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci LA, Connor DF, Morrison R, Melloni RH. Risperidone exerts potent anti-aggressive effects in a developmentally-immature animal model of escalated aggression. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.052. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci LA, Connor DF, Morrison R, Melloni RH., Jr Risperidone exerts potent anti-aggressive effects in a developmentally immature animal model of escalated aggression. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(3):218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci LA, Rasakham S, Grimes JM, Melloni RH. Serotonin 1A receptor activity and expression modulate adolescent anabolic/androgenic steroid induced aggression in hamsters. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci LA, Schwartzer JJ, Melloni RH., Jr Alterations in the anterior hypothalamic dopamine system in aggressive adolescent AAS-treated hamsters. Horm Behav. 2009;55(2):348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Arias M, Minarro J, Aguilar MA, Pinazo J, Simon VM. Effects of risperidone and SCH 23390 on isolation-induced aggression in male mice. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1998;8(2):95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(97)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Arias M, Pinazo J, Minarro J, Stinus L. Effects of SCH 23390, raclopride, and haloperidol on morphine withdrawal-induced aggression in male mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64(1):123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routtenberg A. Intracranial chemical injection and behavior: a critical review. Behav Biol. 1972;7(5):601–641. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(72)80073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaue M, Ago Y, Sowa C, Sakamoto Y, Nishihara B, Koyama Y, Baba A, Matsuda T. Modulation by 5-hT2A receptors of aggressive behavior in isolated mice. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2002;89(1):89–92. doi: 10.1254/jjp.89.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana N, Mengod G, Artigas F. Quantitative Analysis of the Expression of Dopamine D1 and D2 Receptors in Pyramidal and GABAergic Neurons of the Rat Prefrontal Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2008 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Wada JA. Hypothalamically induced defensive behavior and various neuroactive agents. Folia Psychiatr Neurol Jpn. 1974;28(2):101–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1974.tb02291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scerbo AS, Kolko DJ. Salivary testosterone and cortisol in disruptive children: relationship to aggressive, hyperactive, and internalizing behaviors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(8):1174–1184. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199410000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal B, Tremblay RE, Soussignan R, Susman EJ. Male testosterone linked to high social dominance but low physical aggression in early adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(10):1322–1330. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schur SB, Sikich L, Findling RL, Malone RP, Crismon ML, Derivan A, et al. Treatment recommendations for the use of antipsychotics for aggressive youth (TRAAY). Part I: A review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:104–112. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzer JJ, Connor DF, Morrison RL, Ricci LA, Melloni RH., Jr Repeated risperidone administration during puberty prevents the generation of the aggressive phenotype in a developmentally immature animal model of escalated aggression. Physiol Behav. 2008;95(1-2):176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzer JJ, Ricci LA, Melloni RH., Jr Adolescent anabolic-androgenic steroid exposure alters lateral anterior hypothalamic serotonin-2A receptors in aggressive male hamsters. Behav Brain Res. 2009a;199(2):257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzer JJ, Ricci LA, Melloni RH., Jr Interactions between the dopaminergic and GABAergic neural systems in the lateral anterior hypothalamus of aggressive AAS-treated hamsters. Behav Brain Res. 2009b;203(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamans JK, Durstewitz D, Christie BR, Stevens CF, Sejnowski TJ. Dopamine D1/D5 receptor modulation of excitatory synaptic inputs to layer V prefrontal cortex neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(1):301–306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011518798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamans JK, Yang CR. The principal features and mechanisms of dopamine modulation in the prefrontal cortex. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74(1):1–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Ulpian C. Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor selectivities of agonists and antagonists. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;235:55–63. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2723-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley DR, Monsma FJ, Jr, Shen Y. Molecular neurobiology of dopaminergic receptors. Int Rev Neurobiol. 1993;35:391–415. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60573-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Rebec GV. The role of prefrontal cortex D1-like and D2-like receptors in cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;177(3):315–323. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1956-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susman EJ, Inoff-Germain G, Nottelmann ED, Loriaux DL, Cutler GB, Jr, Chrousos GP. Hormones, emotional dispositions, and aggressive attributes in young adolescents. Child Dev. 1987;58(4):1114–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweidan S, Edinger H, Siegel A. The role of D1 and D2 receptors in dopamine agonist-induced modulation of affective defense behavior in the cat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;36(3):491–499. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90246-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweidan S, Edinger H, Siegel A. D2 dopamine receptor-mediated mechanisms in the medial preoptic-anterior hypothalamus regulate effective defense behavior in the cat. Brain Res. 1991;549(1):127–137. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidey JW, Miczek KA. Morphine withdrawal aggression: modification with D1 and D2 receptor agonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;108(1-2):177–184. doi: 10.1007/BF02245304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SM, Kucharik RF, Moyer JA. Effects of serotonergic agents on isolation-induced aggression. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;39(3):729–736. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90155-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CR, Bourque CW, Renaud LP. Dopamine D2 receptor activation depolarizes rat supraoptic neurones in hypothalamic explants. J Physiol. 1991;443:405–419. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Apostolakis EM, O'Malley BW. Distribution of D(5) dopamine receptor mRNA in rat ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;266(2):556–559. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]