Abstract

The Pd-catalyzed cross coupling of racemic tertiary allylic carbonates and allyl boronates is described. This reaction generates all-carbon quaternary centers in a highly regioselective and enantioselective fashion. The outcome of these reactions is consistent with a process that proceeds by way of 3,3’-reductive elimination of bis(η1-allyl)palladium intermediates. Strategies for distinguishing the product alkenes and application to the synthesis of cuparenone are also described.

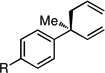

The catalytic enantioselective construction of all-carbon quaternary centers remains a challenging task in organic synthesis.1 Relative to reactions that establish tertiary centers, efficient and selective reactions that form quaternary centers are often much more difficult to develop due to barriers imposed by establishing highly congested carbon centers and due to diminished steric bias between the enantiotopic faces of substrates/intermediates. In terms of catalytic C-C bond-forming quaternary center constructions, enantioselective cycloadditions, Heck reactions,2 enolate α-arylations,3 and enolate α-allylations4 have proven to be valuable strategies. Conjugate addition5 and allylic substitution6 reactions have also proven to be of significant value. Under the purview of Cu-catalysis, SN2’ allylic substitutions can offer high levels of enantiocontrol in the construction of quaternary centers.7 However, these reactions generally require construction of isomerically pure trisubstituted alkene substrates (i.e. A or B, eq. 1). While Ru, W, and Ir complexes undergo branch-selective allylic substitution with either internal or terminal allylic electrophiles, π-σ-π isomerization with these complexes is generally slower than nucleophilic addition such that, similar to copper complexes, the use of isomerically pure substrates is required.8 In contrast, Pd and Mo allyl complexes undergo rapid π-σ-π isomerization and, under appropriate conditions, can favor the branched addition product. This feature allows these complexes to process stereoisomer and regioisomer mixtures of allyl electrophiles (i.e. A–D, eq. 1).9 With these catalysts, remarkable progress has been made in the enantioselective substitution of allylic electrophiles to generate tertiary centers; however, only three examples have appeared that offer a protocol for the asymmetric construction of all-carbon quaternary centers by branch-selective substitution reactions. Trost has described Pd-catalyzed enantioselective substitutions of isoprene monoepoxide, and more recently developed a substrate-specific linalylation reaction.10 Additionally, Hou described the Pd-catalyzed addition of malonates to tertiary allylic acetates where a key requirement for high selectivity is the use of hindered substrates (eg. 1-napthyl derivatives).11 In this manuscript, we detail an effective protocol for Pd-catalyzed enantioselective construction of quaternary centers by allylic substitution. Notably, this reaction employs readily available racemic tertiary allylic carbonates and provides high levels of regio- and enantioselectivity across a range of substrates.

Recently, we described a Pd-catalyzed regio- and enantioselective allyl-allyl cross-coupling that enables the asymmetric assembly of tertiary stereocenters (Scheme 1, R1 = aryl, alkyl; R2 = H).12 Mechanistic experiments suggested that this transformation likely proceeds by way of π-allyl complex 1a/1b, and that a critical feature of the mechanism is the likely intermediacy of bis(η1-allyl)palladium intermediates. These compounds undergo inner-sphere 3,3’-reductive elimination13 (2a/2b, Scheme 1) thereby delivering the branched allylation products selectively. In light of the discussion above, it was of interest to determine whether this reaction could extend to the much more demanding case of quaternary center assembly. A primary concern in developing such a process arises from the fact that with tertiary allylic carbonates, mixtures of syn and anti π-allyl complexes (1a and 1b) would likely be generated and their interconversion, necessary for a stereoconvergent reaction, would require access to hindered η1 tertiary allyl palladium intermediates.

Scheme 1.

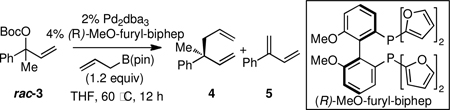

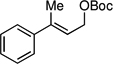

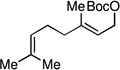

To initiate studies, racemic allyl carbonate 3 was subjected to cross-coupling with allylB(pin), 5 mol % Pd2(dba)3, and 10 mol % MeO-furyl-biphep.14 As depicted in Table 1 (entry 1) this reaction indeed delivered the allyl-allyl coupling product 4 in very high levels of enantiomeric purity; however, a significant amount of 1,3-diene 5 was generated and the reaction proceeded in very low efficiency. While 5 might be produced from an intermediate bis(η1-allyl)Pd complex by intramolecular H-atom abstraction (to generate propene),15 it might also be produced prior to transmetallation by elimination from the allyl intermediate (i.e. 1 or related, Scheme 1).16 That the latter process may operate was verified by treating rac-3 with the catalyst in the absence of allylB(pin); this experiment provided complete conversion to 5 in 12 hours. To minimize this side-reaction during the coupling process, additives thought to accelerate transmetallation were examined. Both Cs2CO317 and CsF18 proved beneficial (entries 2, 3), and in a concentration-dependent manner enhanced the ratio of 4:5. Given that addition of water has also been shown to facilitate transmetallation,19 aqueous solvent systems were examined and were also found to minimize production of the 1,3-diene (entry 6). Optimal conditions were found to involve CsF (3 equiv) and employed 10:1 THF/H2O as the solvent system. In this case, the allyl-allyl coupling product was obtained in excellent yield, enantioselectivity, and as a single (>20:1) regioisomer (entry 7).

Table 1.

Optimization of the Allyl-Allyl Cross Coupling of 3.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | variation to conditions | 4:5a | yield 4b | er 4c |

| 1 | 10% catalyst | 1:1 | 38 | 96:4 |

| 2 | 10% catalyst, Cs2CO3 (1.2 equiv) | 2:1 | 90 | 96:4 |

| 3 | 10% catalyst, CsF (1.2 equiv) | 5:1 | 79 | 96:4 |

| 4 | CsF (3 equiv) | 9:1 | 82 | 95:5 |

| 5 | CsF (10 equiv) | 20:1 | 77 | 95:5 |

| 6 | THF/H2O (10:1) | 14:1 | 88 | 96:4 |

| 7 | CsF (3 equiv), THF/H2O (10:1) | >20:1 | 90 | 96:4 |

Determined by 1H NMR.

Isolated yield of purified product. Compounds 4 and 5 are inseparable by chromatography and the yield refers to the mixture.

Determined by chiral GC chromatography.

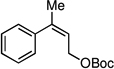

The scope of the catalytic allyl-allyl coupling was examined with a panel of substrates. As depicted in Table 2, a range of aromatic tertiary allylic carbonates participate in the reaction and a good level of substitution is tolerated. Notably, oxygen and halogen-substituted substrates are processed with good yield, and with good chemo- and enantioselectivity. Importantly, ortho substitution is also tolerated in the substrate as the example in entry 8 indicates. In addition to the methyl-ketone-derived electrophiles in entries 1–10, longer alkyl chains and those bearing protected oxygenation are also converted to the chiral 1,5-diene with excellent selectivity. Lastly, the aliphatic substrates in entries 14 and 15 suggest that excellent enantio-discrimination does not require an aromatic substituent. As long as the two enantiotopic groups on the substrate bear a significant difference in size high levels of selectivity can be observed. For example, cyclohexyl and methyl (entry 14) are well distinguished and afford product in 92:8 er whereas the similar size of the alkyl chain and the methyl group in entry 15 results in diminished stereoselection. The example in entry 14 also highlights the fact that allylic halides may serve as coupling partners in this process.

Table 2.

Substrate Scope for the Allyl-Allyl Cross-Coupling.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | product | % yield (pdt:elim)a |

erb |

|

|

|||

| 1 | R=H | 90 (>20:1) | 96:4 | |

| 2 | R=Br | 90 (20:1) | 94:6 | |

| 3 | R=Me | 76 (17:1) | 96:4 | |

| 4c | R=Cl | 70 (>20:1) | 95:5 | |

| 5 |  |

|

86 (>20:1) | 96:4 |

| 6d |  |

|

83 (12:1) | 95:5 |

| 7e |  |

|

80 (11:1) | 96:4 |

| 8f |  |

|

97 (4:1) | 92:8 |

| 9g |  |

|

81 (>20:1) | 95:5 |

| 10c,d |  |

|

94 (6:1) | 96:4 |

| 11d |  |

|

97 (6:1) | 94:6 |

| 12d |  |

|

78 (6:1) | 94:6 |

| 13g |  |

|

58 (>20:1) | 90:10 |

| 14h |  |

|

45 (8:1) | 93:7 |

| 15f |  |

|

96 (4:1) | 76:24 |

Isolated yield of purified product. Ratio of product:1,3-diene (elimination product) determined by 1H NMR analysis. In general, the product and the 1,3-diene are inseparable by chromatography and the yield refers to the mixture.

Determined by chiral GC, SFC or HPLC analysis and is an average of two or more experiments.

Substrate is a mixture of branched and linear allylic carbonates.

Reaction at 80 °C.

Reaction for 36 h.

Reaction employed 10 equiv CsF, 3 equiv allylB(pin), in 5:1 THF:H2O.

Reaction in anhydrous THF.

Reaction employed a mixture of linear and branched allylic chloride substrates.

An important feature of the allyl-allyl cross-coupling reaction is that it can employ racemic tertiary allylic alcohol derivatives, which are readily prepared by addition of vinylmagnesium bromide to the corresponding ketone. However, in some cases the regioisomeric primary allylic electrophile might be more readily available and it is important to know whether these substrates can be employed. As depicted in entries 5–7, both the E and Z terminal allylic carbonates are converted to the same quaternary-center-containing coupling product with similar levels of efficiency and selectivity. One noteworthy difference between the E and Z substrates is that the Z substrate reacts substantially slower (36 h vs. 12 h). It is tenable that in the Z configuration, the aryl group is oriented orthogonal to the alkene σ-framework to avoid an A(1,3) interaction; in this orientation the aryl group may shield the alkene from attack thereby slowing the oxidative addition step.

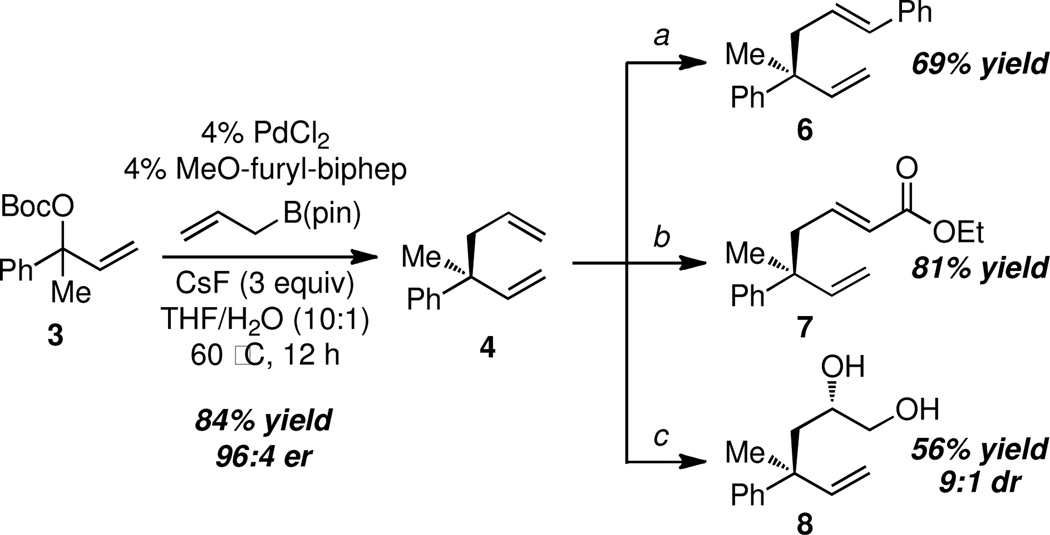

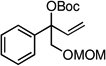

To examine features associated with practicality, the experiments in Scheme 2 were undertaken. First, it was shown that a more economical Pd source, PdCl2, can be employed and that the reaction can be conducted without the aid of a glovebox. Second, it was found that the alkenes in the cross-coupling products could be effectively differentiated, an important pre-requisite for target-directed synthesis. As depicted in Scheme 2, this objective may be accomplished in a number of ways. The reaction in equation 1 shows that a regioselective Heck reaction20 can be accomplished wherein the less hindered alkene is selectively transformed. Ostensibly, the high regioselection in this reaction results from incipient torsional strain should the other olefin undergo migratory insertion with an aryl palladium complex. Likely for similar reasons, olefin cross-metathesis21 converts 4 to unsaturated ester 7 in a highly regio- and stereoselective fashion. Lastly, regio- and diastereoselective dihydroxylation can be accomplished by way of Pt-catalyzed diboration in the presence of a chiral phosphonite catalyst.22 In this case diastereocontrol results from the enantiofacial selectivity that occurs in the diboration step.

Scheme 2.

(a) PhI, 10 mol % Pd(OAc)2, Bu4NCl, DMF, 80 °C, 16 h. (b) 5 mol % HG2 catalyst, ethyl acrylate, CH2Cl2, 40 °C, 20 h. (c) B2(pin)2, 3 mol % Pt(dba)3, 3.6 mol % 3,5-Ph2-taddol-PPh, THF; then NaOH, H2O2.

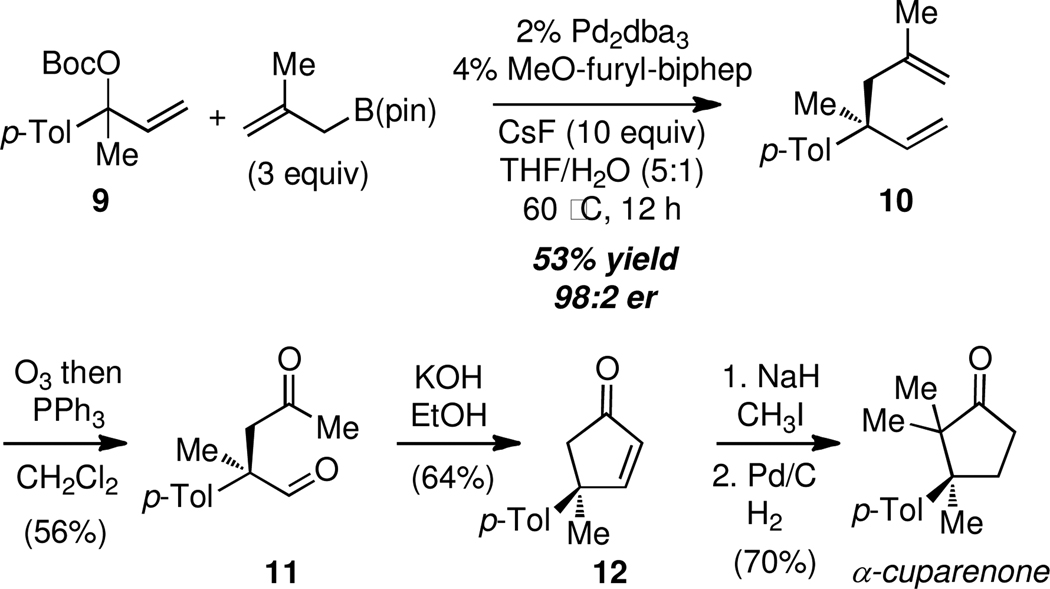

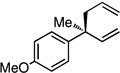

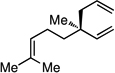

As the preceding data suggests, allylB(pin) can be employed with a broad range of substituted allyl electrophiles. As depicted in Scheme 3, substitution on the allyl boronate is also tolerated. Coupling of carbonate 9 and methallylB(pin) occurs with excellent levels of asymmetric induction. Importantly, reaction product 10 is well suited for construction of cyclopentenones. As depicted, ozonolysis delivers ketoaldehyde 11, which was converted to cyclopentenone 12 by intramolecular aldol condensation. In analogy to a study by Meyers,23 12 was converted to α-cuparenone.24 This five-tep route from 9 represents the shortest catalytic asymmetric synthesis of this target structure.25

Scheme 3.

In conclusion, the 3,3’-reductive elimination reaction that operates in the course of allyl-allyl cross-couplings allows for contrasteric C–C bond constructions between allylic electrophiles and allylboronates. Importantly, these reactions can be used for the asymmetric construction of hindered quaternary carbon centers. Further studies on the utility of these processes are in progress.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Substrate Classes for Allylic Substitution.

Acknowledgment

Support by the NIGMS (GM-64451) and the NSF (DBI-0619576, BC Mass. Spec. Center) is gratefully acknowledged. PZ is grateful for a LaMattina Fellowship. We thank Frontier Scientific for a generous donation of allylB(pin).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Characterization and procedures. This information is available free of charge through the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Das JP, Marek I. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:4593. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05222a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cozzi PG, Hilgraf R, Zimmermann N. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007;5969 [Google Scholar]; (c) Trost BM, Jiang C. Synthesis. 2006;369 [Google Scholar]; (d) Christoffers J, Baro A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005;447:1473. [Google Scholar]; (e) Douglas CJ, Overman LE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307113101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Corey EJ, Guzman-Perez A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:388. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980302)37:4<388::AID-ANIE388>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Overman LE. Pure & Appl. Chem. 1994;66:1423. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shibasaki M, Boden C, Kojima A. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:7371. [Google Scholar]; (c) Shibasaki M, Erasmus MV, Ohshima T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1533. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Review: Bellina F, Rossi R. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1082. doi: 10.1021/cr9000836. Selected references: Liao X, Weng Z, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:195. doi: 10.1021/ja074453g. Chen G, Kwong FY, Chan HO, Yu W, Chan ASC. Chem. Commun. 2006;1413 doi: 10.1039/b601691j. Hamada T, Chieffi A, Åhman J, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:1261. doi: 10.1021/ja011122+. Spielvogel DJ, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3500. doi: 10.1021/ja017545t. Lee S, Hartwig JF. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:3402. doi: 10.1021/jo005761z. Åhman J, Wolfe JP, Troutman MV, Palucki M, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:1918.

- 4.Review: Mohr JT, Stoltz BM. Chem. Asian J. 2007;1476 doi: 10.1002/asia.200700183. Braun M, Meier T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:6952. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602169. Selected references: Mohr JT, Behenna DC, Harned AM, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:6924. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502018. Trost BM, Schroeder GM. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:174. Trost BM, Xu J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2846. doi: 10.1021/ja043472c. Behenna DC, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15044. doi: 10.1021/ja044812x. You S, Hou X, Dai L, Zhu X. Org. Lett. 2001;3:149. doi: 10.1021/ol0067033. Trost BM, Schroeder GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:6759.

- 5.(a) Alexakis A, Bäckvall JE, Krause N, Pàmies O, Diéguez M. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2796. doi: 10.1021/cr0683515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Harutyunyan SR, Hartog T, Geurts K, Minnaard AJ, Feringa BL. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2824. doi: 10.1021/cr068424k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gutnov A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008;27:4547. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hawner C, Alexakis A. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:7295. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02309d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Hoveyda AH, Hird AW, Kacprzynski MA. Chem. Commun. 2004;1779 doi: 10.1039/b401123f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Helmchen G, Ernst M, Paradies G. Pure & Appl. Chem. 2004;76:495. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hartwig JF, Stanley LM. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43:1461. doi: 10.1021/ar100047x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bruneau C, Renaud JL, Demerseman B. Pure & Appl. Chem. 2008;80:861. [Google Scholar]; (e) Lu Z, Ma S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:258. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Review: Falciola CA, Alexakis A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008;3765 Gao F, Lee Y, Mandai K, Hoveyda AH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:8370. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005124. Lee Y, Li B, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11625. doi: 10.1021/ja904654j. Kacprzynski MA, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10676. doi: 10.1021/ja0478779. Luchaco-Cullis CA, Mizutani H, Murphy KE, Hoveyda AH. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:1456. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010417)40:8<1456::AID-ANIE1456>3.0.CO;2-T.

- 8.References pertaining to isomerization of allyl-metal complexes: Iridium: Takeuchi R, Shiga N. Org. Lett. 1999;1:265. Ohmura T, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:15164. doi: 10.1021/ja028614m. Bartels B, García-Yebra C, Rominger F, Helmchen G. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002;2569 Polet D, Alexakis A, Tissot-Croset K, Corminboeuf C, Ditrich K. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:3596. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501180. Stanley LM, Bai C, Ueda M, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8918. doi: 10.1021/ja103779e. Takeuchi R, Ue N, Tanabe K, Yamashita K, Shiga N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:9525. doi: 10.1021/ja0112036. Under appropriate conditions, π-σ-π isomerization with Ir can be rapid, see: Bartels B, Helmchen G. Chem. Commun. 1999;741 Ruthenium: Trost BM, Fraisse PL, Ball ZT. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:1059. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020315)41:6<1059::aid-anie1059>3.0.co;2-5. Tungsten: Lloyd-Jones GC, Pfaltz A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34:462. Prétôt R, Lloyd-Jones GC, Pfaltz A. Pure & Appl. Chem. 1998;70:1035.

- 9.Molybdenum: Selected references: Trost BM, Hachiya I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:1104. Malkov AV, Gouriou L, Lloyd-Jones GC, Starý I, Langer V, Spoor P, Vinader V, Kočovský P. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:6910. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501574. Trost BM, Zhang Y. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:296. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902770. Palladium: Reviews: Trost BM, Van Vranken DL. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:395. doi: 10.1021/cr9409804. Pregosin PS, Salzmann R. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1996;155:35.

- 10.(a) Jiand C, Trost BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12907. doi: 10.1021/ja012104v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM, Malhotra S, Chan WH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:7328. doi: 10.1021/ja2020873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng WH, Sun N, Hou XL. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5151. doi: 10.1021/ol051882f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang P, Brozek LA, Morken JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10686. doi: 10.1021/ja105161f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Méndez M, Cuerva JM, Gómez-Bengoa E, Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. Chem. Eur. J. 2002;8:3620. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020816)8:16<3620::AID-CHEM3620>3.0.CO;2-P. Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. New J. Chem. 2004;28:338. Perez-Rodrguez M, Braga AAC, de Lera AR, Maseras F, Alvarez R, Espinet P. Organometallics. 2010;29:4983. For a related experimentally observable η1-allyl-η1-carboxylate, see: Sherden NH, Behenna DC, Virgil SC, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:6840. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902575.

- 14. Broger EA, Foricher J, Heiser B, Schmid R. 5, 274, 125 U.S. Patent. 1993 For reviews of furyl phosphines, see: Farina V. Pure & Appl. Chem. 1996;68:73. Anderson NG, Keay BA. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:997. doi: 10.1021/cr000024o.

- 15.Keinan E, Kumar S, Dangur V, Vaya J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:11151. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Tsuji J, Yamakawa T, Kaito M, Mandai T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;2075 [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM, Verhoeven TR, Fortunak JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;20:2301. [Google Scholar]; (c) Takacs JM, Lawson EC, Clement F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;119:5956. [Google Scholar]

- 17.For representative examples of the use of Cs2CO3 in Pd-catalyzed cross-couplings: Littke AF, Fu GC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:3387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981231)37:24<3387::AID-ANIE3387>3.0.CO;2-P. Haddach M, McCarthy JR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:3109. Johnson CR, Braun MP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:11014. Molander GA, Ito T. Org. Let. 2001;3:393. doi: 10.1021/ol006896u.

- 18.Wright SW, Hageman DL, McClure LD. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:6095. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Amatore C, Jutand A, Le Duc G. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:2492. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Carrow B, Hartwig J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2116. doi: 10.1021/ja1108326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Suzaki Y, Osakada K. Organometallics. 2006;25:3251. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jeffery T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:2667. Jeffery T. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:10113. For a review of the Heck reaction, see: Beletskaya IP, Cheprakov AV. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:3009. doi: 10.1021/cr9903048.

- 21.(a) BouzBouz S, Simmons R, Cossy J. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3465. doi: 10.1021/ol049079t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Garber SB, Kingsbury JS, Gray BL, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8168. [Google Scholar]; (c) Blackwell HE, O’Leary DJ, Chatterjee AK, Washenfelder RA, Bussman DA, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:58. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kliman LT, Mlynarski SN, Morken JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13210. doi: 10.1021/ja9047762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyers AI, Lefker BA. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:1541. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chetty GL, Dev S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1964;3 [Google Scholar]

- 25.For a comprehensive summary of syntheses of α-cuparenone, see: Natarajan A, Ng D, Yang Z, Garcia-Garibay MA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:6485. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700679.. For catalytic enantioselective synthesis of a similar natural product, enokipodin B, see: Yoshida M, Shoji Y, Shishido K. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1441. doi: 10.1021/ol9001637.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.