Abstract

Rifaximin is a nonabsorbable rifamycin derivative with an excellent safety profile and a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity against a variety of enteropathogens causing acute infectious diarrhea. After oral ingestion, its bioavailability is known to be less than 0.4%, and it has a low potential for significant drug interactions. In the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea caused by noninvasive diarrheagenic Escherichia coli, it has been demonstrated that rifaximin significantly shortens the duration of diarrhea and has an efficacy similar to that of ciprofloxacin. Moreover, according to two randomized placebo-controlled trials, prophylactic treatment with rifaximin reduced the risk of developing travelers’ diarrhea by more than 50% compared with the placebo group. For the treatment of acute diarrhea unrelated to travel, a short course of rifaximin significantly reduced the duration of diarrhea, and its overall efficacy was comparable to that of ciprofloxacin. The discrepancy between the in vitro and in vivoantimicrobial activities of rifaximin, however, and the clinical implication of the rapid appearance of bacterial resistance, must be further elucidated. In conclusion, this gut-selective antibiotic seems to be a promising option for the treatment of acute infectious diarrhea secondary to noninvasive E. coli and also appears to be effective in chemoprophylaxis for travelers’ diarrhea.

Keywords: acute infectious diarrhea, rifaximin, travelers’ diarrhea

Introduction

The duration of the symptoms of acute diarrhea may be said to be less than 2 weeks. More than 90% of acute-diarrhea cases are caused by infectious agents. Diarrhea-producing Escherichia coliis the most frequently identified bacterial pathogen in acute infectious diarrhea, including travelers’ diarrhea [Steffen et al. 1999]. The remaining 10% or so of acute-diarrhea cases are caused by medications, toxic ingestions, ischemia, and other conditions. The pathophysiology underlying acute infectious diarrhea produces specific clinical features that may also be helpful in its diagnosis. Profuse watery diarrhea secondary to small-bowel hypersecretion occurs with the ingestion of enterotoxin-producing bacteria and enteroadherent pathogens. In contrast, cytotoxin-producing and invasive microorganisms cause fever, abdominal pain, and/or bloody diarrhea as well as watery diarrhea. The latter mechanism of diarrhea frequently occurs due to infectious agents acting on the distal small intestine and the large bowel [Camilleri and Murray, 2008].

Rifaximin is a rifamycin-based, nearly nonabsorbable antibiotic with an excellent safety profile [Ojetti et al. 2009]. It was first approved in Italy in 1987 and has been licensed in over 30 countries for the treatment of several gastrointestinal diseases, particularly acute infectious diarrhea such as travelers’ diarrhea [Koo and Dupont, 2010]. Rifaximin was approved in the United States in 2004 for the treatment of uncomplicated travelers’ diarrhea secondary to noninvasive E. coli [Salix Pharmaceuticals, 2008]. In this review, the effectiveness of rifaximin as a therapeutic agent for acute infectious diarrhea is evaluated, and some unsettled issues in relation to rifaximin are addressed.

Antibiotic treatment in acute infectious diarrhea

According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s guidelines for the management of acute infectious diarrhea, empirical antibiotics are commonly recommended without obtaining a fecal specimen in patients with travelers’ diarrhea or febrile dysenteric illness, especially those believed to have moderate-to-severe invasive diseases. Fluoroquinolones are recommended as the first drugs of choice for the empirical treatment of adult patients [Guerrant et al. 2001]. In daily practice, although it is not recommended, the prescription of empirical antibiotics for the treatment of acute-diarrheal patients who do not fall under either of the two situations mentioned in the guidelines sometimes cannot be avoided.

Ciprofloxacin is commonly prescribed for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acute infectious diarrhea, including travelers’ diarrhea. A rapid increase in the rate of fluoroquinolone resistance has emerged since the 1990s, however, in concordance with the widespread use of fluoroquinolones, limiting the usefulness of these agents in Campylobacter infections [Yang et al. 2008; Smith et al. 1999]. Susceptibility tests of enteroaggregative E. coli(EAEC) associated with travelers’ diarrhea showed the emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance [Vila et al. 2001], and a nationwide surveillance over antimicrobial resistance revealed that the prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli steadily increased to 34% of the clinical isolates from 39 hospitals in South Korea [Lee et al. 2004; Chong et al. 1998] and that such fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli made up 15% of the diarrhea-producing E. coliisolated from the acute-diarrheal patients who visited primary care clinics in South Korea [Cho et al. 2008]. In addition, fluoroquinolones are not recommended as the first drugs of choice for children because of concerns regarding the possible emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant pathogens such as Pneumococcus [Murray and Baltimore, 2007].

If accompanied with significant fever (over 38.3°C), bloody diarrhea, or a history of recent antibiotic treatment, infectious gastroenteritis may be attributed to invasive diarrheal pathogens or Clostridium difficile. In these cases, a diagnostic approach to identifying a pathogen should be considered before antibiotic treatment. Although the role of antibiotics is still controversial [Panos et al. 2006], it appears safer not to prescribe antibiotics under conditions where antibiotic treatment may be harmful to the patients, such as in enterohemorrhagic E. coli infection [Dundas et al. 2001; Carter et al. 1987].

Rifaximin pharmacology

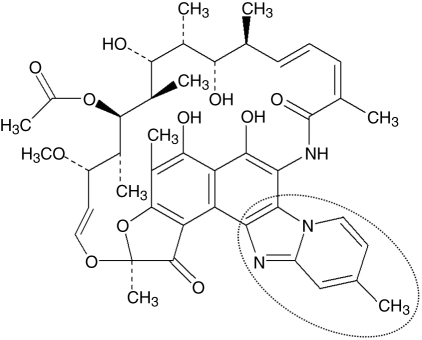

In contrast to the other rifamycins, rifaximin is known to show a stacking self-association behavior in a solution, which pertains to the aggregating tendency of the rifaximin molecule that enables it to form a high-molecular-weighted compound, resulting in the reduction of systemic absorption through passive diffusion [Ojetti et al. 2009]. This process is mediated by an additional pyridoimidazole ring of rifaximin [Huang and Dupont, 2005] (Figure 1). When radiolabeled rifaximin was administered orally, the bioavailability of rifaximin was less than 0.4% in the blood and urine, and 97% was recovered unchanged in stool [Descombe et al. 1994]. After the oral administration of 400 mg rifaximin twice a day for three days to travelers with diarrhea, its fecal level reached extremely high concentrations up to the range of 4000–8000 µg/g [Jiang et al. 2000].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of rifaximin, highlighting the pyridoimidazole ring, which makes rifaximin nonabsorbable.

In vitro studies have shown that rifaximin does not inhibit cytochrome P450 isoenzymes but is capable of inducing the cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) isoenzyme. Based on the results of in vivo rifaximin–midazolam drug interaction studies in patients with normal liver function, however, rifaximin at the recommended dosing regimen is not expected to significantly induce CYP3A4 [Pentikis et al. 2007; Trapnell et al. 2007].

Rifaximin’s in vitromicrobiology

Rifaximin acts by binding to the beta subunit of bacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, resulting in the inhibition of bacterial RNA synthesis, the same mechanism as that of structural analogues such as rifampin [Gillis and Brodgen, 1995]. An extensive microbiological survey demonstrated that the minimum inhibitory concentration for 90% of microorganism growth (MIC90) ranged from 4 to 64 µg/ml for enteric pathogens isolated from stool specimens from travelers’ diarrhea patients spanning three continents, including the enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and EAEC, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Plesiomonas, and Aeromonas species [Gomi et al. 2001; Jiang et al. 2000]. Other studies have confirmed similar bacterial-susceptibility patterns showing the broad spectrum of antimicrobial action, covering Gram-positive and Gram-negative and both aerobes and anaerobes [Ruiz et al. 2007; Sierra et al. 2001a, 2001b].

Travelers’ diarrhea

Travelers’ diarrhea is defined as a condition where there are three or more unformed stools within a 24-h period, together with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or cramps, fecal urgency, tenesmus, or the passage of bloody or mucoid stools. It is usually a self-limited illness that typically lasts 2 weeks, and is rarely life-threatening even without treatment [Dupont and Ericsson, 1993]. It can cause complications such as dehydration, however, and needs antibiotic treatment to reduce the duration of the diarrhea [Ericsson, 2003]. Although a variety of bacterial, viral, and parasitic organisms can cause travelers’ diarrhea, diarrhea-producing E. coli predominates. There have been four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that demonstrated the efficacy of rifaximin for the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea [Taylor et al. 2006; Steffen et al. 2003; Dupont et al. 2001, 1998] (Table 1). The primary endpoint in these trials was the time to the last unformed stool (TLUS), defined as the time from the first dose of medication to the passage of the last unformed stool, after which the patient already feels well.

Table 1.

Efficacy of rifaximin for the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea.

| Dupont et al.[1998] | Dupont et al.[2001] | Steffen et al.[2003] | Taylor et al.[2006] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 72 | 187 | 380 | 399 |

| Duration | 5 days | 3 days | 3 days | 3 days |

| Treatments (Median TLUS) | Rif 200 t.i.d. (26.3 h) | Rif 400 b.i.d. (25.7 h) | Rif 200 t.i.d. (32.5 h) | Rif 200 t.i.d. (32.0 h) |

| Rif 400 t.i.d. (40.5 h) | Cip 500 b.i.d. (25.0 h) | Rif 400 t.i.d. (32.9 h) | Cip 500 b.i.d. (28.8 h) | |

| Rif 600 t.i.d. (35.0 h) | Placebo (60.0 h) | Placebo (65.5 h) | ||

| TMP-SMX b.i.d. (47.0 h) |

TLUS, time to the last unformed stool.

Rif 200 t.i.d., 200 mg rifaximin three times a day.

Cip 500 b.i.d., 500 mg ciprofloxacin twice a day.

TMP-SMX b.i.d., 160/800 mg trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole twice a day.

An earlier dose-finding RCT with four treatment arms was performed in 72 travelers to Mexico; no significant differences in TLUS were shown among the 5-day courses of rifaximin (200, 400, and 600 mg three times a day) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX; 160/800 mg twice a day) [Dupont et al. 1998]. Unexpectedly, a trend of a shorter TLUS with the administration of 200 mg rifaximin three times a day was shown. One RCT compared the effectiveness of 3-day courses of 400 mg rifaximin twice a day with that of 3-day courses of 500 mg ciprofloxacin twice a day for diarrheal treatment in 187 travelers to Mexico or Jamaica [Dupont et al. 2001]. The median TLUS (rifaximin 25.7 h vs. ciprofloxacin 25.0 h, p = 0.47), clinical-cure rates (87% vs. 88%, respectively; p = 0.80), and microbiological-cure rates (74% vs. 88%, respectively; p = 0.22) of the two antibiotics were similar.

The efficacy of rifaximin orally taken at a dose of 200 mg three times a day for 3 days, the currently recommended dose for acute diarrhea, was evaluated in two RCTs in adult patients with travelers’ diarrhea [Taylor et al. 2006; Steffen et al. 2003]. One study with three treatment arms was conducted in 380 patients at clinical sites in Mexico, Guatemala, and Kenya (study 1) [Steffen et al. 2003]. The study participants were randomized to receive either 3-day courses of rifaximin (200/400 mg three times a day) or placebo. Stool specimens were collected before and after treatment. For both rifaximin dosages, the median TLUS was significantly shorter compared with the placebo (32.5 and 32.9 h vs. 60.0 h, respectively; p = 0.001). Moreover, the participants in the rifaximin groups showed better clinical responses than the placebo group (79.2% and 81.0% vs. 60.5%, p = 0.001). Nevertheless, the microbiologic-eradication rates based on the posttreatment fecal cultures in the participants with at least one pathogen before treatment were not significantly different across the treatment groups, and it was the same in the subgroup with ETEC identified from the stool specimens [Steffen et al. 2003].

The other study that evaluated the efficacy of rifaximin orally taken at a dose of 200 mg three times a day for 3 days was conducted in 399 patients in Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, and India (study 2) [Taylor et al. 2006]. The study participants were randomized to receive either 3-day courses of rifaximin, ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice a day), or placebo. Stool specimens were collected before treatment and 1–3 days after the end of treatment, to identify the enteric pathogens. The median TLUS was shorter in the rifaximin group than in the placebo group (32.0 h vs. 65.5 h, p = 0.001) and was similar to that of the ciprofloxacin group (28.8 h, p = 0.35). The percentage of patients in the rifaximin group who experienced clinical cure (77%) was higher than that in the placebo group (61%, p = 0.004), but was the same as that in the ciprofloxacin group (78%) [Taylor et al. 2006]. The results of study 2 supported the results presented for study 1. In addition, study 2 showed that rifaximin treatment for patients who experienced fever and/or blood in their stool at baseline had a prolonged TLUS [Taylor et al. 2006]. Many patients with fever and/or bloody diarrhea were proven to have invasive pathogens, such as Campylobacter jejuni, Shigella species, and Salmonella species, isolated in the baseline stool. Rifaximin treatment for patients who had C. jejuni isolated as a sole pathogen at baseline failed and resulted in a poor clinical cure rate of 23.5%, the same as that for placebo. Moreover, the microbiologic-eradication rate for patients with C. jejuni isolated at baseline was much lower than the eradication rates seen for E. coli (33% vs. 79%, respectively). Therefore, based on the results of this study, other antibiotics should be chosen in regions where invasive pathogens are expected to be responsible for the significant number of travelers’ diarrhea cases, such as in Goa, India [Taylor et al. 2006].

Overall, rifaximin is more effective than placebo and has a similar efficacy to the traditional antibiotics for travelers’ diarrhea treatment, such as TMP-SMX and ciprofloxacin, in shortening the duration of diarrhea. Moreover, in all four RCTs on the use of rifaximin for the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea, the rates of adverse events in the rifaximin-treated patients were not different from those in the ciprofloxacin- or placebo-treated patients [Taylor et al. 2006; Steffen et al. 2003; Dupont et al. 2001, 1998].

Prevention of travelers’ diarrhea

Owing to the emergence of antimicrobial resistance and to the self-limited nature of travelers’ diarrhea, the antibiotic chemoprophylaxis for travelers’ diarrhea is still controversial. Persistent and chronic complications, however, such as postinfectious irritable-bowel syndrome (IBS), which is known to occur in 5–10% of the patients experiencing travelers’ diarrhea, and symptom aggravations in patients with established functional bowel disorder [Dupont et al. 2010; Okhuysen et al. 2004], have led to the need for travelers’ diarrhea chemoprophylaxis. Nevertheless, there are still no data supporting the role of antibiotics in the prevention of postinfectious IBS. There have been two RCTs, however, that showed the efficacy of rifaximin as a chemoprophylactic agent for travelers’ diarrhea [Martinez-Sandoval et al. 2010; Dupont et al. 2005].

In the first trial with four treatment arms, 210 travelers to Mexico were randomized to receive 200 mg rifaximin once a day, 200 mg twice a day, or 200 mg three times a day, for 2 weeks, or placebo [Dupont et al. 2005]. As a result, 15% of the participants in the three rifaximin dosage groups developed travelers’ diarrhea as opposed to 54% in the placebo group (p = 0.0001). The protection rate of rifaximin against travelers’ diarrhea was 72%. Regardless of the dose regimens, rifaximin was shown to be superior to placebo for the prevention of travelers’ diarrhea. There was no significant difference, however, in the median log counts of the fecal coliform bacteria among the treatment groups after receiving 2 weeks of rifaximin or placebo [Dupont et al. 2005].

In the second trial with two treatment arms, 210 travelers to Mexico were randomized to either 200 mg rifaximin three times a day for 2 weeks or to placebo [Martinez-Sandoval et al. 2010]. The participants in the rifaximin group were less likely to develop travelers’ diarrhea compared with those in the placebo group (20% vs. 48%, respectively; p < 0.0001), and rifaximin showed a travelers’ diarrhea protection rate of 58% [Martinez-Sandoval et al. 2010].

Acute diarrhea unrelated to travel

Although rifaximin was approved only for the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea in the United States, it is indicated for infectious diarrhea independent of the travel history in most other countries where rifaximin is marketed, including South Korea [Koo and Dupont, 2010]. There are a number of clinical trials suggesting that rifaximin is effective for the treatment of infectious diarrhea in nontravelers [Della Marchina et al. 1988; Luttichau et al. 1985]. In an open-label study, 20 hospitalized adults with acute enterocolitis were successfully treated with rifaximin and experienced clinical improvement [Luttichau et al. 1985]. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 121 elderly patients, a 7-day course of 200 mg rifaximin three times a day was more effective than placebo in reducing the frequency of unformed stools and the duration of symptoms, associated with a better pathogen eradication rate (79% vs. 53%, respectively) [Della Marchina et al. 1988].

Recently, a double-blind, multicenter RCT was performed with 143 moderate-to-severe acute-diarrheal patients who visited the gastroenterology clinics in nine hospitals in South Korea [Hong et al. 2010]. More than 85% of the patients in the rifaximin and ciprofloxacin groups had no travel history for a 6-month period before their enrollment. The intent-to-treat analysis showed no significant difference between the 3-day courses of 400 mg rifaximin twice a day and 500 mg ciprofloxacin twice a day in the median TLUS (34.0 h vs. 35.0 h, respectively; p = 0.163), general wellness (67% vs. 78%, respectively; p = 0.189), and treatment failure (9% vs. 12%, respectively; p = 0.841). These results suggest that a 3-day course of 400 mg rifaximin twice a day is as effective as the same course of 500 mg ciprofloxacin twice a day for the treatment of acute infectious diarrhea in nontravelers [Hong et al. 2010].

Clostridium difficile infection

Although rifaximin has shown excellent in vitro activity against C. difficile[Hoover et al. 1993; Ripa et al. 1987; Lamanna and Orsi, 1984], the clinical studies evaluating the efficacy of rifaximin for the treatment of C. difficileinfection (CDI) are limited to case reports and one small randomized nonblind trial with 20 CDI patients, in which rifaximin showed a good response rate even though the clinical resolution of CDI was somewhat slower than that of vancomycin [Boero et al. 1990]. There were few case series evaluating rifaximin use for recurrent CDI. Rifaximin was shown to be effective for both the treatment and prevention of recurrent CDI, with response rates of 83% and 88% [Garey et al. 2009; Johnson et al. 2007], respectively. In one case report, the extended co-administration of rifaximin and oral vancomycin for 7 weeks successfully treated refractory CDI [Berman, 2007].

Through a bacterial-susceptibility test to rifampin, which is being used as a surrogate assay because the E-test strip for rifaximin is not available, significant resistance to rifampin was shown among the C. difficile isolates, particularly in epidemic BI/NAP1 strains [O'Connor et al. 2008]. In one institution, approximately 81% of the C. difficile isolates were found to be resistant to rifampin [Curry et al. 2009]. In addition, the paucity of double-blind RCTs still makes physicians hesitate to prescribe rifaximin for the treatment of patients with CDI.

Unsettled issues related to the use of rifaximin for the treatment of acute infectious diarrhea

Discrepancies between the in vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activities of rifaximin

Rifaximin is known to have in vitro antimicrobial activity against a broad spectrum of enteric pathogens, including invasive pathogens such as C. jejuni, Salmonella species, and Shigella species [Gomi et al. 2001]. In addition, a pharmacokinetic study reported an extremely high fecal concentration of rifaximin after oral ingestion [Jiang et al. 2000]. Nevertheless, the in vivo effect of rifaximin was disappointing in patients in whom invasive pathogen(s) were isolated [Taylor et al. 2006]. Moreover, rifaximin has an insignificant effect on colonic bacterial flora or ETEC, according to prior culture studies of the stool specimens from travelers’ diarrhea patients [Dupont et al. 2005; Dupont and Jiang, 2004; Steffen et al. 2003].

As rifaximin is a largely nonabsorbable antibiotic, it seems reasonable that a low tissue concentration of it will result in a poor in vivo response in patients with invasive pathogen(s). The minimal effect of rifaximin on colonic flora and fecal pathogens, including ETEC, can at least be partly attributed to rifaximin’s water insolubility [Darkoh et al. 2010; Huang and Dupont, 2005]. Many compounds can exist as polymorphs (crystalline forms with different arrangements of the same molecule in the solid state), between which chemical and physical properties such as solubility may differ [Henwood et al. 2000]. This is particularly important for pharmaceutical products as the drug efficacy and safety may be altered. Five distinct crystal forms of rifaximin (α, β, γ, δ, and ε) have been identified and characterized. Rifaximin in any form can be defined as practically water-insoluble, but at a concentration of less than 0.1 mg/ml water [Viscomi et al. 2008]. Reportedly, an extremely high fecal concentration of rifaximin after oral ingestion was determined after the no physiologic dissolution of rifaximin from stool specimens using an organic solvent [Jiang et al. 2000]. Therefore, such a high fecal concentration of rifaximin may not necessarily result in the eradication of colonic flora or diarrhea-producing E. colicontained in feces.

ETEC and EAEC are both prevalent pathogens identified in more than half of the Travelers’ diarrhea cases [Taylor et al. 2006; Infante et al. 2004], and are small-bowel pathogens. Bile acid absorption occurs mostly in the distal small bowel via diffusion and active transport mechanisms, which returns the bile acid to the liver via the portal vein and completes the enterohepatic circulation. This process is so efficient that the reabsorption rate reaches more than 95% [Dowling, 1973]. The higher bile concentration in the small intestine than in the colon is a possible explanation of rifaximin’s differential effects in the treatment of small-bowel infections. Recently, an in vitro study where the antimicrobial effect and solubility of rifaximin in an aqueous solution was evaluated in the presence and absence of bile acids showed rifaximin to be 70- to 120-fold more soluble in physiologic concentrations of bile acids than in an aqueous solution. As a result, the addition of bile acids to rifaximin at a subinhibitory concentration significantly improved the drug’s anti-ETEC effect by 71% [Darkoh et al. 2010]. The exact in vivo action mechanism of rifaximin, however, including its possible interaction with bile acids, must be further elucidated.

Resistance issues of rifaximin

It is a general concern that bacterial resistance emerges in proportion to the use of antibacterial agents. Rifampin, a rifamycin derivative related to rifaximin, is known as a major stimulant for the selection of a resistant strain during its administration. The bacterial resistance to rifampin appears to be related to a chromosomal point mutation in the rpoB gene, which encodes for the drug-binding domain of the beta subunit of the bacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerase [O'Connor et al. 2008; Williams et al. 1998]. Significant resistance to rifampin has been demonstrated by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and epidemic BI/NAP1 C. difficile strains [Curry et al. 2009; Soro et al. 1997; Musser, 1995]. A recent in vitro study showed discordance, however, between the susceptibility of C. difficile isolates to rifaximin and rifampin, although different methodologies were applied (i.e., agar dilution for rifaximin and E strips for rifampin), and there was only a slight absolute difference in the resistance rate between rifaximin and rifampin (2% vs. 8%, respectively) [Johnson et al. 2009]. Therefore, C. difficile resistance to rifaximin itself, the correlation between rifampin and rifaximin, and potential association with clinical failure must be further studied [Koo and Dupont, 2010].

Several studies have shown rifaximin resistance in the fecal flora of individuals who received rifaximin at a dose of 600–1200 mg/day for 3–5 days [Dupont and Jiang, 2004; De Leo et al. 1986; Eftimiadi et al. 1984]. No significant increases in the numbers of rifaximin-resistant coliforms were found in the immediate or 2-day posttreatment samples [Dupont and Jiang, 2004], however, and the resistance rates decreased to less than 20% of the fecal flora 1–2 weeks after the end of rifaximin treatment [De Leo et al. 1986]. Jiang and Dupont reported that the development of resistance to rifaximin is primarily due to a chromosomal one-step alteration in the drug target, DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, which differs from the plasmid-mediated resistance commonly acquired by bacteria against aminoglycoside antibiotics. They reported that the resistant strains appeared unstable and unable to persistently colonize the intestinal tract [Jiang and Dupont, 2005]. Nevertheless, only in vitro resistance data are available, and there has been no clinical study that compared the treatment failure rate of rifaximin in patients with susceptible pathogens to that in patients with resistant pathogens. Despite such limitations, the currently available data seem to suggest that bacterial resistance is not a major concern of the short-term rifaximin therapy for the treatment of acute infectious diarrhea, except CDI.

Conclusions

Rifaximin is a nonabsorbable rifamycin derivative that has an excellent safety profile, lacks significant drug interactions, and has a minor effect on colonic flora. This gut-selective antibiotic seems to be a promising option for the treatment of acute infectious diarrhea, including travelers’ diarrhea secondary to noninvasive E. coli, and also appears to be effective in the chemoprophylaxis for travelers’ diarrhea.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- Berman A.L. (2007) Efficacy of rifaximin and vancomycin combination therapy in a patient with refractory Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Gastroenterol 41: 932–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boero M., Berti E., Morgando A. (1990) Treatment of colitis caused by Clostridium difficile: results of an open random study between rifaximin and vancomycin. Microbiol Med 5: 74–77 [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M., Murray J.A. Diarrhea and constipation. In: Fauci A.S., Braunwald E., Kasper D.L., Hauser S.L., Longo D.L., Jameson J.L., et al. (eds). (2008) Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine McGraw-Hill: New York [Google Scholar]

- Carter A.O., Borczyk A.A., Carlson J.A., Harvey B., Hockin J.C., Karmali M.A., et al. (1987) A Severe outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7-associated hemorrhagic colitis in a nursing home. N Engl J Med 317: 1496–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S.H., Shin H.H., Choi Y.H., Park M.S., Lee B.K. (2008) Enteric bacteria isolated from acute diarrheal patients in the Republic of Korea between the year 2004 and 2006. J Microbiol 46: 325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong Y., Lee K., Park Y.J., Jeon D.S., Lee M.H., Kim M.Y., et al. (1998) Korean nationwide surveillance of antimicrobial resistance of bacteria in 1997. Yonsei Med J 39: 569–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry S.R., Marsh J.W., Shutt K.A., Muto C.A., O'leary M.M., Saul M.I., et al. (2009) High frequency of rifampin resistance identified in an epidemic Clostridium difficile clone from a large teaching hospital. Clin Infect Dis 48: 425–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkoh C., Lichtenberger L.M., Ajami N., Dial E.J., Jiang Z.D., Dupont H.L. (2010) Bile acids improve the antimicrobial effect of rifaximin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54: 3618–3624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo C., Eftimiadi C., Schito G.C. (1986) Rapid disappearance from the intestinal tract of bacteria resistant to rifaximin. Drugs Exp Clin Res 12: 979–981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Marchina M., Renzi G., Palazzini E. (1988) Infectious diarrhea in the aged: controlled clinical trial of rifaximin. Chemioterapia 7: 336–340 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descombe J.J., Dubourg D., Picard M., Palazzini E. (1994) Pharmacokinetic study of rifaximin after oral administration in healthy volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 14: 51–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling R.H. (1973) The enterohepatic circulation of bile acids as they relate to lipid disorders. J Clin Pathol Suppl (Assoc Clin Pathol) 5: 59–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundas S., Todd W.T., Stewart A.I., Murdoch P.S., Chaudhuri A.K., Hutchinson S.J. (2001) The Central Scotland Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreak: risk factors for the hemolytic uremic syndrome and death among hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis 33: 923–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont H.L., Ericsson C.D. (1993) Prevention and treatment of traveler’s diarrhea. N Engl J Med 328: 1821–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont H.L., Ericsson C.D., Mathewson J.J., Palazzini E., Dupont M.W., Jiang Z.D., et al. (1998) Rifaximin: a nonabsorbed antimicrobial in the therapy of travelers' diarrhea. Digestion 59: 708–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont H.L., Galler G., Garcia-Torres F., Dupont A.W., Greisinger A., Jiang Z.D. (2010) Travel and travelers' diarrhea in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg 82: 301–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont H.L., Jiang Z.D. (2004) Influence of rifaximin treatment on the susceptibility of intestinal Gram-negative flora and Enterococci. Clin Microbiol Infect 10: 1009–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont H.L., Jiang Z.D., Ericsson C.D., Adachi J.A., Mathewson J.J., Dupont M.W., et al. (2001) Rifaximin versus ciprofloxacin for the treatment of traveler's diarrhea: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis 33: 1807–1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont H.L., Jiang Z.D., Okhuysen P.C., Ericsson C.D., De La Cabada F.J., Ke S., et al. (2005) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin to prevent travelers' diarrhea. Ann Intern Med 142: 805–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eftimiadi C., Deleo C., Schito G. (1984) Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with L/105, a new non-absorbable rifamycin. Drugs Exp Clin Res 10: 691–696 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson C.D. (2003) Travellers' diarrhoea. Int J Antimicrob Agents 21: 116–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey K.W., Jiang Z.D., Bellard A., Dupont H.L. (2009) Rifaximin in treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: an uncontrolled pilot study. J Clin Gastroenterol 43: 91–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis J.C., Brogden R.N. (1995) Rifaximin. a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in conditions mediated by gastrointestinal bacteria. Drugs 49: 467–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomi H., Jiang Z.D., Adachi J.A., Ashley D., Lowe B., Verenkar M.P., et al. (2001) In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacterial enteropathogens causing traveler's diarrhea in four geographic regions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45: 212–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrant R.L., Van Gilder T., Steiner T.S., Thielman N.M., Slutsker L., Tauxe R.V., et al. (2001) Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 32: 331–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood S.Q., De Villiers M.M., Liebenberg W., Lotter A.P. (2000) Solubility and dissolution properties of generic rifampicin raw materials. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 26: 403–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover W.W., Gerlach E.H., Hoban D.J., Eliopoulos G.M., Pfaller M.A., Jones R.N. (1993) Antimicrobial activity and spectrum of rifaximin, a new topical rifamycin derivative. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 16: 111–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K., Kim Y., Han D., Choi C., Jang B., Park Y., et al. (2010) Efficacy of rifaximin compared with ciprofloxacin for the treatment of acute infectious diarrhea: a randomized controlled multicenter study. Gut Liver 4: 357–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D.B., Dupont H.L. (2005) Rifaximin—a novel antimicrobial for enteric infections. J Infect 50: 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante R.M., Ericsson C.D., Jiang Z.D., Ke S., Steffen R., Riopel L., et al. (2004) Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli diarrhea in travelers: response to rifaximin therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2: 135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z.D., Dupont H.L. (2005) Rifaximin: in vitro and in vivo antibacterial activity—a review. Chemotherapy 51: 67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z.D., Ke S., Palazzini E., Riopel L., Dupont H. (2000) In vitro activity and fecal concentration of rifaximin after oral administration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44: 2205–2206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S., Schriever C., Galang M., Kelly C.P., Gerding D.N. (2007) Interruption of recurrent clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea episodes by serial therapy with vancomycin and rifaximin. Clin Infect Dis 44: 846–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S., Schriever C., Patel U., Patel T., Hecht D.W., Gerding D.N. (2009) Rifaximin redux: treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infections with rifaximin immediately post-vancomycin treatment. Anaerobe 15: 290–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo H.L., Dupont H.L. (2010) Rifaximin: a unique gastrointestinal-selective antibiotic for enteric diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 26: 17–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamanna A., Orsi A. (1984) In vitro activity of rifaximin and rifampicin against some anaerobic bacteria. Chemioterapia 3: 365–367 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Kim Y.A., Park Y.J., Lee H.S., Kim M.Y., Kim E.C., et al. (2004) Increasing prevalence of vancomycin-resistant Enterococci, and cefoxitin-, imipenem- and fluoroquinolone-resistant gram-negative bacilli: a Konsar study in 2002. Yonsei Med J 45: 598–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttichau U., Arcangeli P., Sinapi S. (1985) The use of rifaximin in the treatment of acute diarrhoeal enteritis: open study. Panminerva Med 27: 129–132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Sandoval F., Ericsson C.D., Jiang Z.D., Okhuysen P.C., Romero J.H., Hernandez N., et al. (2010) Prevention of travelers' diarrhea with rifaximin in US travelers to Mexico. J Travel Med 17: 111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray T.S., Baltimore R.S. (2007) Pediatric uses of fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Pediatr Ann 36: 336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser J.M. (1995) Antimicrobial agent resistance in mycobacteria: molecular genetic insights. Clin Microbiol Rev 8: 496–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor J.R., Galang M.A., Sambol S.P., Hecht D.W., Vedantam G., Gerding D.N., et al. (2008) Rifampin and rifaximin resistance in clinical isolates of Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52: 2813–2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojetti V., Lauritano E.C., Barbaro F., Migneco A., Ainora M.E., Fontana L., et al. (2009) Rifaximin pharmacology and clinical implications. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 5: 675–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okhuysen P.C., Jiang Z.D., Carlin L., Forbes C., Dupont H.L. (2004) Post-diarrhea chronic intestinal symptoms and irritable bowel syndrome in North American travelers to Mexico. Am J Gastroenterol 99: 1774–1778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panos G.Z., Betsi G.I., Falagas M.E. (2006) Systematic review: are antibiotics detrimental of beneficial for the treatment of patients with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 24: 731–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentikis H.S., Connolly M., Trapnell C.B., Forbes W.P., Bettenhausen D.K. (2007) The effect of multiple-dose, oral rifaximin on the pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral midazolam in healthy volunteers. Pharmacotherapy 27: 1361–1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripa S., Mignini F., Prenna M., Falcioni E. (1987) In vitro antibacterial activity of rifaximin against Clostridium difficile, Campylobacter jejuni and Yersinia spp. Drugs Exp Clin Res 13: 483–488 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz J., Mensa L., O'callaghan C., Pons M.J., Gonzalez A., Vila J., et al. (2007) In vitro antimicrobial activity of rifaximin against enteropathogens causing traveler's diarrhea. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 59: 473–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salix Pharmaceuticals Xifaxan (rifaximin) tablet [prescribing information] 2008Salix Pharmaceuticals: Palo Alto, CA [Google Scholar]

- Sierra J.M., Navia M.M., Vargas M., Urassa H., Schellemberg D., Gascon J., et al. (2001a) In vitro activity of rifaximin against bacterial enteropathogens causing diarrhoea in children under 5 years of age in Ifakara, Tanzania. J Antimicrob Chemother 47: 904–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra J.M., Ruiz J., Navia M.M., Vargas M., Vila J. (2001b) In vitro activity of rifaximin against enteropathogens producing traveler's diarrhea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45: 643–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K.E., Besser J.M., Hedberg C.W., Leano F.T., Bender J.B., Wicklund J.H., et al. (1999) Quinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni infections in Minnesota, 1992–1998. Investigation Team. N Engl J Med 340: 1525–1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soro O., Pesce A., Raggi M., Debbia E.A., Schito G.C. (1997) Selection of rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis does not occur in the presence of low concentrations of rifaximin. Clin Microbiol Infect 3: 147–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen R., Collard F., Tornieporth N., Campbell-Forrester S., Ashley D., Thompson S., et al. (1999) Epidemiology, etiology, and impact of traveler's diarrhea in Jamaica. JAMA 281: 811–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen R., Sack D.A., Riopel L., Jiang Z.D., Sturchler M., Ericsson C.D., et al. (2003) Therapy of travelers' diarrhea with rifaximin on various continents. Am J Gastroenterol 98: 1073–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D.N., Bourgeois A.L., Ericsson C.D., Steffen R., Jiang Z.D., Halpern J., et al. (2006) A randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of rifaximin compared with placebo and with ciprofloxacin in the treatment of travelers' diarrhea. Am J Trop Med Hyg 74: 1060–1066 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C.B., Connolly M., Pentikis H., Forbes W.P., Bettenhausen D.K. (2007) Absence of effect of oral rifaximin on the pharmacokinetics of ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate in healthy females. Ann Pharmacother 41: 222–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila J., Vargas M., Ruiz J., Espasa M., Pujol M., Corachan M., et al. (2001) Susceptibility patterns of enteroaggregative Escherichia coliassociated with traveller's diarrhoea: emergence of quinolone resistance. J Med Microbiol 50: 996–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viscomi G., Campana M., Barbanti M., Grepioni F., Polito M., Confortini D., et al. (2008) Crystal forms of rifaximin and their effect on pharmaceutical properties. Cryst Eng Comm 10: 1074–1081 [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.L., Spring L., Collins L., Miller L.P., Heifets L.B., Gangadharam P.R., et al. (1998) Contribution of rpoB mutations to development of rifamycin cross-resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42: 1853–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.R., Wu H.S., Chiang C.S., Mu J.J. (2008) Pediatric Campylobacteriosis in Northern Taiwan from 2003 to 2005. BMC Infect Dis 8: 151–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]