Abstract

Background

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is associated with major cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Abnormalities in nitric oxide metabolism due to excess of the NO synthase inhibitor asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) may be pathogenic in PAD. We explored the association between ADMA levels and markers of atherosclerosis, function, and prognosis.

Methods and Results

133 patients with symptomatic PAD were enrolled. Ankle brachial index (ABI), walking time, vascular function measures (arterial compliance and flow-mediated vasodilatation) and plasma ADMA level were assessed for each patient at baseline. ADMA correlated inversely with ABI (r = −0.238, p=0.003) and walking time (r = −0.255, p = 0.001), independent of other vascular risk factors. We followed up 125 (94%) of our 133 initial subjects with baseline measurements (mean 35 months). Subjects with ADMA levels in the highest quartile (>0.84 μmol/L) showed significantly greater occurrence of MACE compared to those with ADMA levels in the lower 3 quartiles (p = 0.001). Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis revealed that ADMA was a significant predictor of MACE, independent of other risk factors including age, gender, blood pressure, smoking history, diabetes and ABI (Hazard ratio = 5.1, p<0.001). Measures of vascular function, such as compliance, FMVD and blood pressure, as well as markers of PAD severity, including ABI and walking time, were not predictive.

Conclusion

Circulating levels of ADMA correlate independently with measures of disease severity and major adverse cardiovascular events. Agents that target this pathway may be useful for this patient population.

Keywords: peripheral arterial disease, asymmetric dimethylarginine, nitric oxide, prognosis, atherosclerosis

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) of the lower extremities affects 8 to 12 million individuals in the United States1, 2. PAD is an arterial occlusive disease that is typically secondary to atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis begins with a loss of endothelial homeostasis, and persistent endothelial dysfunction contributes to the progression of vascular disease. Endothelial dysfunction is reflected by a reduction in bioactive endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO)3,4. By virtue of its ability to suppress platelet adhesion, immune cell infiltration and vascular smooth muscle proliferation, endothelial NO is vasoprotective5,6,7,8. Individuals with an impairment of this pathway are at increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events9,10. Endothelial vasodilator dysfunction, as assessed by brachial artery flow-mediated dilation in PAD patients referred for vascular surgery, is an independent predictor of cardiovascular events11. One cause of this endothelial dysfunction may be an elevation in plasma levels of the endogenous inhibitor of NO synthase, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA)12. Endogenous ADMA is derived largely from the degradation of proteins containing methylated arginine residues. Approximately 20% of ADMA is cleared by the kidney, whereas the remainder is metabolized by the enzyme dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH). Accordingly, in mice overexpressing DDAH, plasma ADMA levels are reduced, NO synthesis is enhanced, and vascular resistance is reduced13. Notably, these animals have enhanced endothelial regeneration and resistance to vascular lesion formation14, 15. By contrast, in DDAH deficient mice, plasma ADMA levels are increased, NO synthesis is reduced, and vascular resistance is increased16. These studies indicate that by suppressing NO synthesis, increased plasma ADMA levels may increase the susceptibility to vascular disease. An intriguing link between cardiovascular risk factors and endothelial dysfunction is suggested by evidence that elevated levels of glucose, homocysteine, or oxidized LDL cholesterol impair endothelial DDAH activity and thereby increase ADMA levels17–19.

Plasma levels of ADMA are increased in individuals with cardiovascular risk factors18, 20. Because of the link between plasma ADMA, vascular function and cardiovascular disease, we hypothesized that elevated plasma ADMA levels may adversely effect vascular patency and function, functional capacity and/or event-free survival in patients with PAD.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 133 patients with symptomatic PAD were enrolled as part of the Nitric Oxide in Peripheral Arterial Insufficiency (NO-PAIN) study21. In the NO-PAIN study, subjects were recruited by advertisements targeting individuals with leg pain that limited their ability to walk21. After informed consent, subjects underwent a physical examination, ankle and brachial systolic blood pressure measurements. Venipuncture was performed in a fasting state, and serum and plasma samples were stored at −75°C.

Exercise treadmill testing (ETT) employed the Skinner-Gardner protocol22. The baseline values for initial claudication distance (ICD) and absolute claudication distance (ACD) were the average of values obtained from two consecutive treadmill tests. Subjects underwent two to four ETTs in the run-in period to obtain two consecutive ETTs where the lower of the two ACD values was within 25% of the higher value. Subjects with persistent variability in ACD greater than the acceptable range were excluded after four ETTs. Other exclusion criteria are as published previously21. The NO-PAIN study was funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and approved and monitored by the Stanford University Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Ankle-brachial index (ABI)

ABI is defined as the ratio of systolic blood pressure (SBP) at the ankle to that in the brachial artery, and an ABI<0.90 is an established criterion for PAD23. The limb pressures were obtained using a hand-held Doppler and blood pressure cuff as previously described and ABI calculated for each leg by dividing the highest ankle SBP (posterior tibial or dorsalis pedis) by the higher of the two brachial pressures24.

Exercise performance and walking ability

Subjects performed an ETT using the Skinner-Gardner protocol, which consists of a graded workload with a constant speed of 2 mph (3.2 km/hr) and an increase in grade of 2% every 2 minutes15. During the ETT, standardized verbal encouragement was given, and all subjects were continuously monitored for hemodynamic responses to exercise (heart rate, rhythm and blood pressure).

Initial claudication distance (ICD) was measured as the distance in meters walked on the ETT at the onset of claudication, regardless of whether this was manifested as muscle pain, ache, cramps, numbness or fatigue. The peak walking time (PWT) for this study was defined as the time walked on the ETT before having to stop due to claudication.

Vascular Function

Vascular function was assessed by measurement of vascular compliance and flow-mediated vasodilatation (FMVD). These studies were carried out with the subject in a supine position in a quiet room with low illumination. All studies were conducted in the morning, after a 12-hour fast and with medications withheld for 12 hours. Additionally, all participants were placed on a low nitrate diet for 24 hours preceding the endothelial function tests.

Vascular compliance was measured as previously described25 using the HDI Cardiovascular Profilor® (model DO 2020; Hypertension Diagnostics, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), which combines noninvasive pulse waveform compliance. A modified Windkessel formula is used to determine capacitive compliance (C1), which reflects a large vessel (i.e. proximal aorta and major branches) compliance, and oscillatory compliance (C2), which is a measure of small vessel (i.e. distal arteries) compliance that can be used as a marker of endothelial function. The results are expressed in ml/mmHg × 10 (C1) and ml/mmHg × 100 (C2). C2 has been shown to correlate moderately with FMVD in patients with type 2 diabetes and healthy controls26. FMVD of the brachial artery was measured using a Siemens Acuson Sequoia C256 high-resolution ultrasound machine (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Malvern, PA) using a 14 mHz probe and established techniques8. The diameter of the brachial artery was assessed at rest and after reactive hyperemia. A blood pressure cuff was placed on the forearm below the transducer and inflated to a pressure of 50mmHg above the patient's systolic pressure for a period of 5 minutes. Measurements of brachial artery diameter were performed 30, 45 and 60 seconds after cuff deflation. Prior studies have shown that the peak blood flow occurs within 60 seconds after cuff deflation27. Arterial diameter was measured using electronic calipers. FMVD is expressed as a percentage change in vessel diameter from rest to post-reactive hyperemia.

Laboratory studies

Prior to testing, patients ingested a low-nitrate diet for 24 hours and fasted overnight. They were also given low-nitrite water to consume for 12 hours before blood and urine samples were collected for safety laboratory studies, urinary and plasma nitrogen oxide levels, amino acid analysis and plasma ADMA levels. Venous blood was collected into EDTA coated tubes on ice. The samples were centrifuged immediately and stored at −80°C. Nitrogen oxide measurements were performed by Greiss reaction using a colorimetric assay28; plasma arginine, ornithine and citrulline were measured using an amino acid analyzer; and plasma ADMA was measured by immunoassay29.

Follow-up

Using a standardized questionnaire, two trained interviewers conducted follow-up phone interviews on the subjects. The patients were reminded of the time of their baseline measurements and asked when they were hospitalized for the following events since that time: heart attack, stroke, heart surgery, balloon angioplasty or stenting. If subjects had died, their next of kin was contacted to obtain the date of death. Major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) was predefined as one of the following: myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary, cerebral, or peripheral revascularization procedure and all-cause mortality.

Statistical considerations

Data was examined for normality of distribution, and log transformation and/or non-parametric tests were used where appropriate. ADMA levels were skewed and so log transformed. The levels are reported as median and interquartile range. Outcome from subject recruitment to the end of the study was then compared between subjects with the highest quartile of ADMA versus the lower three quartiles of plasma ADMA. Censoring was defined by time to MACE or time to death. The proportional hazards assumption was tested as part of the analysis. Correlations between variables were assessed on transformed data and multivariate regression was used for assessments of independence of correlations. Multivariate models were predefined and variables such as CVD risk factors which are known or suspected to be associated with changes in ABI, walking time and/or MACE were included in models. Predefined variables for the analysis included ADMA level, age, gender, blood pressure, renal function, smoking history, diabetes and ABI. A p value of <0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance. Cox regression was performed on the patient cohort. Data was analyzed using SPSS software. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study (MDRD) method30.

Results

Subject demographics, medications and biochemistry are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The median level of ADMA in this cohort was 0.78 μmol/l and the interquartile range was 0.68 to 0.84. Risk factor modifying therapies are not optimally employed in patients with PAD31,32 and this is true of the subjects at the time of entry into this study. Consistent with their advanced vascular disease, subjects manifested severe endothelial vasodilator dysfunction as assessed by FMVD (Table 3). One-third of subjects showed no flow-mediated vasodilation or even a paradoxical vasocontriction. Subjects had elevated pulse pressure and reduced C2 (oscillatory arterial compliance), each of which indicate reduced arterial compliance.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics and Medications

| AD MA Quartile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.68 μmol/l | 0.68–0.78 μmol/l | 0.78–0.84 μmol/l | >0.84 μmol/l | p value | |

| Age (yrs) | 71 ± 7 | 73 ± 9 | 74 ± 7 | 72 ± 10 | 0.68 |

| Gender (%male) | 72 | 73 | 84 | 76 | 0.64 |

| Any smoking (%) | 81 | 94 | 78 | 76 | 0.22 |

| Hypertension (%) | 62 | 73 | 59 | 67 | 0.70 |

| Diabetes (%) | 34 | 24 | 22 | 33 | 0.60 |

| Coronary Artery Disease (%) | 31 | 55 | 41 | 39 | 0.35 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 88 | 76 | 66 | 73 | 0.24 |

| Medication | |||||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/ ARB | 40 | 53 | 50 | 57 | 0.93 |

| Beta Blocker | 38 | 42 | 41 | 55 | 0.14 |

| HMG CoA Reductase Inhibitor | 66 | 64 | 62 | 67 | 0.99 |

| Antiplatelet agent | 66 | 70 | 50 | 48 | 0.20 |

Table 2.

Biochemistry

| ADMA Quartile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.68 μmol/l | 0.68–0.78 μmol/l | 0.78–0.84 μmol/l | >0.84 μmol/l | p value | |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 182.4 ± 54.9 | 188.3 ± 43.7 | 182.2 ± 39.2 | 177.7 ± 36.3 | 0.82 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 101.9 ± 44.8 | 98.3 ± 28.2 | 104.9 ± 34.7 | 102.2 ± 33.2 | 0.91 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 47.9 ± 11.1 | 53.9 ± 22.5 | 47.4 ± 10.7 | 48.5 ± 15.7 | 0.32 |

| Triglycerides(mg/dl) | 169.3 ± 140.3 | 180.5 ± 167.4 | 165.5 ± 119.4 | 135.1 ± 76.3 | 0.54 |

| Insulin (IU/ml) | 10.5 ± 4.6 | 12.4 ± 7.9 | 15.7 ± 12.8 | 21.2 ± 37.3 | 0.18 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 122.4 ± 48.8 | 124.7 ± 59.9 | 103.2 ± 22.4 | 109.2 ± 26.6 | 0.13 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.10 |

Abbreviations: LDL = low density lipoprotein, HDL = high density lipoprotein, ADMA = asymmetric dimethylarginine

Table 3.

Vascular Function Measures and ADMA

| ADMA Quartile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.68 μmol/l | 0.68–0.78 μmol/l | 0.78–0.84 μmol/l | >0.84 μmol/l | p value | |

| FMD (%) | 3.2 ± 6.3 | 3.8 ± 5.0 | 2.5 ± 5.9 | 4.0 ± 7.5 | 0.79 |

| C2 (ml/mmHg × 100) | 3.2 ± 1.8 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 3.0 ± 1.8 | 0.98 |

| ABI | 0.55 ± 0.19 | 0.59 ± 0.16 | 0.60 ± 0.19 | 0.56 ± 0.21 | 0.68 |

| PWT (sec) | 363.3 ± 160.8 | 328.6 ± 149.1 | 335.2 ± 179.2 | 319.5 ± 158.1 | 0.72 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 155.8 ± 22.7 | 155.1 ± 20.9 | 142.6 ± 20.1 | 151.0 ± 20.6 | 0.06 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 78.0 ± 10.2 | 79.3 ± 12.6 | 75.2 ± 10.8 | 75.6 ± 10.0 | 0.39 |

Abbreviations: FMD = flow mediated dilatation, C2 = oscillatory compliance, ABI = ankle brachial index, PWT = peak walking time, SBP = systolic blood pressure, DBP = diastolic BP

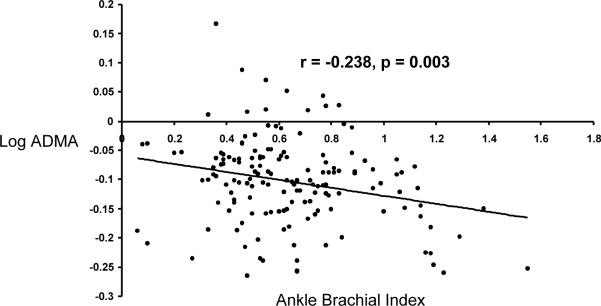

Plasma ADMA levels correlated inversely with ABI (r = −0.238, p =0.003; Fig. 1) and with PWT (r = −0.255, p = 0.001). These relationships were independent of other vascular risk factors in a multivariate model (Tables 4), however the relationship with PWT was attenuated by including ABI in the model. Other significant correlates of reduced ABI included current or any history of smoking and elevated pulse pressure, while correlates of reduced PWT included age, high fasting glucose and current or any smoking history. In terms of other vascular function measures, C2 related weakly to ADMA (r = −0.166, p = 0.041) by univariate correlation, while FMVD did not show any association with ADMA in this study (r = 0.023, p = 0.780).

Figure 1.

Relationship Between Plasma ADMA and Index Ankle Brachial Index

Table 4.

Multivariate Correlates of Ankle Brachial Index

| Coefficient | SE coefficient | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −0.001956 | 0.003183 | 0.540 |

| Gender | −0.0003726 | 0.0006859 | 0.588 |

| Current Smoking | −0.0026891 | 0.0008483 | 0.002 |

| Ever Smoked | −0.0023992 | 0.0006396 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | −0.0006783 | 0.0007614 | 0.375 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | −0.12721 | 0.09324 | 0.175 |

| LDL – Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 0.0009141 | 0.0006242 | 0.145 |

| Log ADMA | −0.7928 | 0.2750 | 0.005 |

| HDL – Cholesterol (mg/dl) | −0.09303 | 0.09508 | 0.330 |

| Trigylcerides (mg/dl) | −0.2774 | 0.1866 | 0.139 |

| Glomerular Filtration Rate (ml/min/1.73m2) | −0.000187 | 0.001120 | 0.868 |

| Pulse Pressure (mmHg) | −0.003785 | 0.001131 | 0.001 |

Significant values bolded

Abbreviations: SE = standard error, LDL = low density lipoprotein, HDL = high density lipoprotein, ADMA = asymmetric dimethylarginine

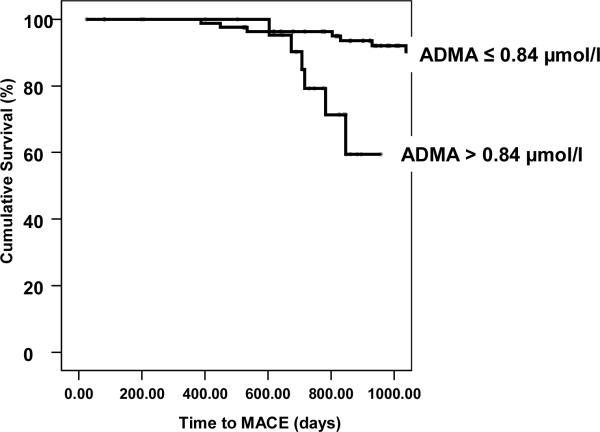

We obtained follow-up on 125 (94%) of 133 subjects who underwent the baseline measurements, with mean follow-up duration of 35 months. At least 1 MACE was incurred by 49 (39%) of 125 patients during the follow-up period. Subjects with ADMA levels in the highest quartile (>0.84 μmol/L) showed significantly greater occurrence of MACE compared to those with ADMA levels in the lower 3 quartiles (Figure 2; p = 0.001). The hazard ratio for incidence of MACE for those with elevated ADMA in the highest quartile was 5.1 (95% confidence interval 2.1 – 12.1, p<0.001) (Table 5). There was no significant difference in terms of predicting outcome between the lower three quartiles of ADMA level. Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis revealed that ADMA was a significant predictor of death, independent of other risk factors including age, gender, blood pressure, smoking history, diabetes and ABI (p = 0.001) (Table 6). In contrast, measures of vascular function such as FMVD, C2 and blood pressure as well as markers of PAD severity (ABI and PWT) were not predictive of subsequent cardiovascular events or death when cardiovascular risk factors and ADMA were included in the model (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Highest Quartile of ADMA and MACE

Highest quartile of ADMA versus lower 3 quartiles MACE pre defined as myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary, cerebral, or peripheral revascularization procedure and all-cause mortality (p = 0.001, Cox regression, adjusted for age and gender)

Table 5.

MACE and ADMA Quartile

| ADMA Quartile (μmol/l) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| <0.68 | 0.4 (0.2,1.0) | 0.042 |

| 0.68 – 0.78 | 0.7 (0.3, 1.4) | 0.261 |

| 0.78 – 0.84 | 1.2 (0.6,2.6) | 0.641 |

| >0.84 | 5.2 (2.3, 11.7) | <0.001 |

Table 6.

Predictors of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in the No- Pain Study Cox Proportional Hazards Regression

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.5 (0.6,3.5) | 0.366 |

| Age (years) | 1.0 (1.0,1.0) | 0.794 |

| Smoker | 0.6(0.2,1.6) | 0.320 |

| Diabetes | 0.9 (0.4,1.9) | 0.812 |

| ABI | 0.8 (0.2, 3.8) | 0.733 |

| PWT (secs) | 1.0 (1.0,1.0) | 0.168 |

| GFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 1.1 (0.5, 2.3) | 0.870 |

| LDL-Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 1.0 (1.0,1.0) | 0.966 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 1.0 (1.0,1.0) | 0.655 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 1.0 (1.0,1.0) | 0.964 |

| ADMA (highest quartile) | 5.1 (2.1, 12.1) | <0.001 |

ADMA = asymmetric dimethylarginine, SBP = systolic blood pressure, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, PWT = peak walking time, GFR = glomerular filtration rate, LDL = low density lipoprotein, ABI = ankle brachial index.

(Overall Model X2 = 19.8, p < 0.05)

Discussion

In a cohort of subjects with symptomatic PAD and a high cardiovascular risk factor burden, we find that plasma ADMA is an independent prognosticator of major adverse cardiovascular events. In this high risk population, plasma ADMA is a better predictor than the traditional cardiovascular risk factors, other measures of vascular function or PAD severity. Plasma ADMA level also correlates with the degree of arterial disease, as measured by ABI, and with exercise capacity, as measured by PWT. Our study confirms and extends previous work suggesting that ADMA influences vascular function and the progression of vascular disease in humans.

Evidence that ADMA influences vascular reactivity and disease

In animals overexpressing DDAH, plasma ADMA levels may be reduced by 0.4–1.0 uM. These small changes in plasma ADMA levels are vasoprotective, and are associated with a substantive increase in NO synthesis, improved endothelial regeneration, and resistance to vascular lesion formation13–15. Increased plasma levels of ADMA appear to suppress NO synthesis, and impair vascular functions. In healthy humans, ADMA infusion causes increased arterial stiffness, reduced cerebral blood flow, increased systemic vascular resistance and reduced renal blood flow33,34. In healthy subjects with cardiovascular risk factors, plasma ADMA is elevated and correlates with endothelial vasodilator dysfunction18,20. These studies suggest that plasma ADMA may mediate the endothelial vasodilator dysfunction induced by cardiovascular risk factors. Indeed, administration of methionine to healthy young subjects increases plasma homocysteine levels, which is associated with an increase in plasma ADMA and a decline in flow-mediated vasodilation. Finally, plasma ADMA levels are elevated in a spectrum of disease states characterized by impaired vascular reactivity, such as pre-eclampsia and idiopathic pulmonary hypertension35,36. These findings are consistent with the effect of ADMA to inhibit synthesis of the endothelium-derived vasodilator NO.

Because endothelium derived NO has vasoprotective effects, one might anticipate that long-term elevation of plasma ADMA and inhibition of NO synthesis could contribute to progression of vascular disease. Indeed, plasma ADMA levels independently predict the degree of coronary artery calcification in young adults. In a nested case-control study within the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) cohort, young adults in the highest tertile of plasma ADMA levels had twice the risk of coronary artery calcification, after adjustment for all of the traditional cardiovascular risk factors, renal function and C-reactive protein37. In asymptomatic middle-aged individuals without a history of vascular disease, plasma ADMA level is an independent predictor of carotid intima-media thickness (IMT)38. Plasma ADMA is associated with macrovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus39.

ADMA predicts vascular morbidity and mortality

Plasma ADMA levels are increased in PAD subjects compared to age and gender matched controls, in association with a reduction in urinary nitrogen oxides40. Furthermore, plasma ADMA appears to be a predictor of cardiovascular morbidity. Mittermayer and colleagues prospectively assessed the occurrence of MACE (myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft, stroke, carotid revascularization, death) in 496 patients with PAD over a median of 19 months41. MACE occurred in 39% of the patients in the highest quartile versus 26% of those in the lowest quartile of plasma ADMA, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.70 for those in the highest quartile. Our investigation confirms the association of plasma ADMA with cardiovascular morbidity in PAD patients and extends this by showing a relationship with measures of disease severity and morrtality. We did not find any significant difference among the lower three quartiles of ADMA in terms of prognostic information, suggesting that the relationship between ADMA and future cardiovascular risk may not be linear. This type of non-linearity between circulating risk factors and prognosis is not uncommon, such as in the case of hsCRP. Furthermore, in our longer term study, we were able to observe that ADMA is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality. Finally, we show that plasma ADMA is superior to measurements of vascular function (vascular compliance and flow-mediated vasodilation) as a prognosticator.

ADMA, Vascular Function and Prognosis

One of the strengths of our study is that all subjects were highly characterized with respect to endothelial function and PAD severity markers. We were able to show that plasma ADMA was a superior prognosticator by comparison to vascular function measures such as FMVD and arterial compliance. Our cohort consisted of relatively elderly patients with significantly impaired vascular function measures. As a group, our subjects had evidence of severely impaired FMVD with many exhibiting constrictor responses. Thus, it is possible that the expected relationship between ADMA and FMVD, and the relationship between FMVD and MACE, are lost at such extremes of endothelial dysfunction. Of note, plasma ADMA was also a superior prognosticator by comparison to the standard measures of PAD severity, ABI and PWT.

Correlates of Maximal Claudication Time in Patients with PAD

Plasma ADMA, age, fasting glucose and smoking history were inversely correlated with PWT, whereas there was a modest positive correlation between ABI and PWT. The strong association observed with smoking history underscores the importance of cigarette smoking as a risk factor in PAD. Our analysis suggests that a remote history of smoking is a risk factor for reduced PWT, even independent of current smoking. While smoking cessation improves outcome in PAD with respect to its complications42, it does not in itself significantly improve walking distance30,43. Such finding highlights the importance of inquiring about prior, as well as present, exposure to cigarette smoking when risk-stratifying patients with PAD.

Significance for Therapy

ADMA is a competitive inhibitor of the metabolism of L-arginine by NO synthase. Thus, it seems logical to reverse the inhibition by administration of the NO precursor. Indeed, short-term administration of L-arginine restores endothelial vasodilator function in subjects with cardiovascular risk factors or disease44,45. Unfortunately, this short-term benefit does not seem to persist. Indeed, long-term administration of supplemental L-arginine may even impair endothelial vasodilator function and increase cardiovascular events25,46.

By contrast, treatment with thiazolidinediones, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists reduce plasma ADMA levels47. Plasma ADMA levels are elevated in patients admitted with acute coronary syndrome and falls rapidly with therapy to modify CVD risk factors48. In patients with PAD and critical limb ischemia, therapy with iloprost was associated with reduction in ADMA and clinical improvement in a small observational study49. It is not known if a reduction in plasma ADMA contributes to the established benefit of these therapies. This question may be answered by the development of new pharmacotherapies to specifically reduce plasma ADMA levels, such as agonists of DDAH expression or activity.

Study limitations

The study was not powered to assess differences between ADMA quartiles however this relationship between highest levels and risk has been seen with other biomarkers as discussed above, including in the limited number of studies of ADMA in this field. Such associations do not imply causation nor is the direction of the association determined by this study. We were not able to correct for the influence of all medications and this is an important consideration.

Conclusion

Circulating levels of the NO synthase inhibitor, ADMA, correlate independently with measures of disease severity; with major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with PAD. Elevations in plasma ADMA may provide a pathophysiological link between cardiovascular risk factors and their effect on endothelial function and on progression of disease. Therapeutic strategies that specifically target and/or influence the NO synthase pathway may enhance functional capacity and survival of patients with PAD.

Trial registration: NHLBI; NCT00284076; http://clinicaltrials.gov

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 HL75774, R21 HL085743, and K12 HL087746), and by the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award

Footnotes

Disclosures Dr. Cooke is the inventor of patents owned by Stanford University for diagnostic and therapeutic applications of the NOS pathway from which he receives royalties.

References

- 1.Brevetti G, Oliva G, Silvestro A, Scopacasa F, Chiariello M. Prevalence, risk factors and cardiovascular comorbidity of symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in Italy. Atherosclerosis. 2004;175(1):131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Criqui MH, Vargas V, Denenberg JO, Ho E, Allison M, Langer RD, Gamst A, Bundens WP, Fronek A. Ethnicity and peripheral arterial disease: the San Diego Population Study. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2703–2707. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.546507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludmer PL, Selwyn AP, Shook TL, Wayne RR, Mudge GH, Alexander RW, Ganz P. Paradoxical vasoconstriction induced by acetylcholine in atherosclerotic coronary arteries. The New England journal of medicine. 1986;315(17):1046–1051. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198610233151702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oemar BS, Tschudi MR, Godoy N, Brovkovich V, Malinski T, Luscher TF. Reduced endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and production in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1998;97(25):2494–2498. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.25.2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooke JP, Singer AH, Tsao P, Zera P, Rowan RA, Billingham ME. Antiatherogenic effects of L-arginine in the hypercholesterolemic rabbit. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1992;90(3):1168–1172. doi: 10.1172/JCI115937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke JP. NO and angiogenesis. Atheroscler Suppl. 2003;4(4):53–60. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5688(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhlencordt PJ, Chen J, Han F, Astern J, Huang PL. Genetic deficiency of inducible nitric oxide synthase reduces atherosclerosis and lowers plasma lipid peroxides in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Circulation. 2001;103(25):3099–3104. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.25.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooke JP, Dzau VJ. Nitric oxide synthase: role in the genesis of vascular disease. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:489–509. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schachinger V, Zeiher AM. Atherosclerosis-associated endothelial dysfunction. Zeitschrift fur Kardiologie. 2000;89(Suppl 9):IX, 70–74. doi: 10.1007/s003920070033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeboah J, Crouse JR, Hsu FC, Burke GL, Herrington DM. Brachial flow-mediated dilation predicts incident cardiovascular events in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2007;115(18):2390–2397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang AL, Silver AE, Shvenke E, Schopfer DW, Jahangir E, Titas MA, Shpilman A, Menzoian JO, Watkins MT, Raffetto JD, Gibbons G, Woodson J, Shaw PM, Dhadly M, Eberhardt RT, Keaney JF, Jr., Gokce N, Vita JA. Predictive value of reactive hyperemia for cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral arterial disease undergoing vascular surgery. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2007;27(10):2113–2119. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.147322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooke JP. Asymmetrical dimethylarginine: the Uber marker? Circulation. 2004;109(15):1813–1818. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126823.07732.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dayoub H, Achan V, Adimoolam S, Jacobi J, Stuehlinger MC, Wang BY, Tsao PS, Kimoto M, Vallance P, Patterson AJ, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase regulates nitric oxide synthesis: genetic and physiological evidence. Circulation. 2003;108(24):3042–3047. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000101924.04515.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka M, Sydow K, Gunawan F, Jacobi J, Tsao PS, Robbins RC, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase overexpression suppresses graft coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;112(11):1549–1556. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konishi HWJ, Sydow K, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) promotes endothelial repair after vascular injury. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.068. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leiper J, Nandi M, Torondel B, Murray-Rust J, Malaki M, O'Hara B, Rossiter S, Anthony S, Madhani M, Selwood D, Smith C, Wojciak-Stothard B, Rudiger A, Stidwill R, McDonald NQ, Vallance P. Disruption of methylarginine metabolism impairs vascular homeostasis. Nature medicine. 2007;13(2):198–203. doi: 10.1038/nm1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito A, Tsao PS, Adimoolam S, Kimoto M, Ogawa T, Cooke JP. Novel mechanism for endothelial dysfunction: dysregulation of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circulation. 1999;99(24):3092–3095. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stuhlinger MC, Abbasi F, Chu JW, Lamendola C, McLaughlin TL, Cooke JP, Reaven GM, Tsao PS. Relationship between insulin resistance and an endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. Jama. 2002;287(11):1420–1426. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin KY, Ito A, Asagami T, Tsao PS, Adimoolam S, Kimoto M, Tsuji H, Reaven GM, Cooke JP. Impaired nitric oxide synthase pathway in diabetes mellitus: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine and dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circulation. 2002;106(8):987–992. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027109.14149.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boger RH, Bode-Boger SM, Szuba A, Tsao PS, Chan JR, Tangphao O, Blaschke TF, Cooke JP. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA): a novel risk factor for endothelial dysfunction: its role in hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1998;98(18):1842–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.18.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oka RK, Szuba A, Giacomini JC, Cooke JP. A pilot study of L-arginine supplementation on functional capacity in peripheral arterial disease. Vascular medicine (London, England) 2005;10(4):265–274. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm637oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiatt WR, Hirsch AT, Regensteiner JG, Brass EP. Clinical trials for claudication. Assessment of exercise performance, functional status, and clinical end points. Vascular Clinical Trialists. Circulation. 1995;92(3):614–621. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fowkes FG. The measurement of atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease in epidemiological surveys. Int J Epidemiol. 1988;17(2):248–254. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDermott MM, Feinglass J, Slavensky R, Pearce WH. The ankle-brachial index as a predictor of survival in patients with peripheral vascular disease. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(8):445–449. doi: 10.1007/BF02599061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson AM, Harada R, Nair N, Balasubramanian N, Cooke JP. L-arginine supplementation in peripheral arterial disease: no benefit and possible harm. Circulation. 2007;116(2):188–195. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson AM, O'Neal D, Nelson CL, Prior DL, Best JD, Jenkins AJ. Comparison of arterial assessments in low and high vascular disease risk groups. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(4):285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, Celermajer D, Charbonneau F, Creager MA, Deanfield J, Drexler H, Gerhard-Herman M, Herrington D, Vallance P, Vita J, Vogel R. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39(2):257–265. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01746-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marzinzig M, Nussler AK, Stadler J, Marzinzig E, Barthlen W, Nussler NC, Beger HG, Morris SM, Jr., Bruckner UB. Improved methods to measure end products of nitric oxide in biological fluids: nitrite, nitrate, and S-nitrosothiols. Nitric Oxide. 1997;1(2):177–189. doi: 10.1006/niox.1997.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulze F, Wesemann R, Schwedhelm E, Sydow K, Albsmeier J, Cooke JP, Boger RH. Determination of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) using a novel ELISA assay. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42(12):1377–1383. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2004.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Annals of internal medicine. 1999;130(6):461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okaa RK, Umoh E, Szuba A, Giacomini JC, Cooke JP. Suboptimal intensity of risk factor modification in PAD. Vascular medicine (London, England) 2005;10(2):91–96. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm611oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, Regensteiner JG, Creager MA, Olin JW, Krook SH, Hunninghake DB, Comerota AJ, Walsh ME, McDermott MM, Hiatt WR. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. Jama. 2001;286(11):1317–1324. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kielstein JT, Impraim B, Simmel S, Bode-Boger SM, Tsikas D, Frolich JC, Hoeper MM, Haller H, Fliser D. Cardiovascular effects of systemic nitric oxide synthase inhibition with asymmetrical dimethylarginine in humans. Circulation. 2004;109(2):172–177. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105764.22626.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kielstein JT, Donnerstag F, Gasper S, Menne J, Kielstein A, Martens-Lobenhoffer J, Scalera F, Cooke JP, Fliser D, Bode-Boger SM. ADMA increases arterial stiffness and decreases cerebral blood flow in humans. Stroke. 2006;37(8):2024–2029. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000231640.32543.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savvidou MD, Hingorani AD, Tsikas D, Frolich JC, Vallance P, Nicolaides KH. Endothelial dysfunction and raised plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine in pregnant women who subsequently develop pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1511–1517. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kielstein JT, Bode-Boger SM, Hesse G, Martens-Lobenhoffer J, Takacs A, Fliser D, Hoeper MM. Asymmetrical dimethylarginine in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2005;25(7):1414–1418. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000168414.06853.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iribarren C, Husson G, Sydow K, Wang BY, Sidney S, Cooke JP. Asymmetric dimethyl-arginine and coronary artery calcification in young adults entering middle age: the CARDIA Study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(2):222–229. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000230108.86147.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyazaki H, Matsuoka H, Cooke JP, Usui M, Ueda S, Okuda S, Imaizumi T. Endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor: a novel marker of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1999;99(9):1141–1146. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krzyzanowska K, Mittermayer F, Krugluger W, Schnack C, Hofer M, Wolzt M, Schernthaner G. Asymmetric dimethylarginine is associated with macrovascular disease and total homocysteine in patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189(1):236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boger RH, Bode-Boger SM, Thiele W, Junker W, Alexander K, Frolich JC. Biochemical evidence for impaired nitric oxide synthesis in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Circulation. 1997;95(8):2068–2074. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.8.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mittermayer F, Krzyzanowska K, Exner M, Mlekusch W, Amighi J, Sabeti S, Minar E, Muller M, Wolzt M, Schillinger M. Asymmetric dimethylarginine predicts major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with advanced peripheral artery disease. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2006;26(11):2536–2540. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000242801.38419.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hiatt WR. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;344(21):1608–1621. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith I, Franks PJ, Greenhalgh RM, Poulter NR, Powell JT. The influence of smoking cessation and hypertriglyceridaemia on the progression of peripheral arterial disease and the onset of critical ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11(4):402–408. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(96)80170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Creager MA, Gallagher SJ, Girerd XJ, Coleman SM, Dzau VJ, Cooke JP. L-arginine improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in hypercholesterolemic humans. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1992;90(4):1248–1253. doi: 10.1172/JCI115987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drexler H, Fischell TA, Pinto FJ, Chenzbraun A, Botas J, Cooke JP, Alderman EL. Effect of L-arginine on coronary endothelial function in cardiac transplant recipients. Relation to vessel wall morphology. Circulation. 1994;89(4):1615–1623. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulman SP, Becker LC, Kass DA, Champion HC, Terrin ML, Forman S, Ernst KV, Kelemen MD, Townsend SN, Capriotti A, Hare JM, Gerstenblith G. L-arginine therapy in acute myocardial infarction: the Vascular Interaction With Age in Myocardial Infarction (VINTAGE MI) randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2006;295(1):58–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maas R. Pharmacotherapies and their influence on asymmetric dimethylargine (ADMA) Vascular medicine (London, England) 2005;10(Suppl 1):S49–57. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm605oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bae SW, Stuhlinger MC, Yoo HS, Yu KH, Park HK, Choi BY, Lee YS, Pachinger O, Choi YH, Lee SH, Park JE. Plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine concentrations in newly diagnosed patients with acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris during two weeks of medical treatment. The American journal of cardiology. 2005;95(6):729–733. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blardi P, de Lalla A, Pieragalli D, De Franco V, Meini S, Ceccatelli L, Auteri A. Effect of iloprost on plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine and plasma and platelet serotonin in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2006;80(3–4):175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]