Abstract

Yersinia pestis, the causative organism of plague, is a zoonotic organism with a worldwide distribution. Although the last plague epidemic occurred in early 1900s, human cases continue to occur due to contact with infected wild animals. In this study, we have developed a reservoir-targeted vaccine against Y. pestis, to interrupt transmission of disease in wild animals as a potential strategy for decreasing human disease. A vaccinia virus delivery system was used to express the F1 capsular protein and the LcrV type III secretion component of Y. pestis as a fusion protein. Here we show that a single dose of this vaccine administered orally, generates a dose-dependent antibody response in mice. Antibody titers peak by 3 weeks after administration and remain elevated for a minimum of 45 weeks. Vaccination provided up to 100% protection against challenge with Y. pestis administered by intranasal challenge at 10 times the lethal dose with protection lasting a minimum of 45 weeks. An orally available, vaccinia virus expressed vaccine against Y. pestis may be a suitable vaccine for a reservoir targeted strategy for the prevention of enzootic plague.

1. INTRODUCTION

Yersinia pestis, the etiological agent of plague, is a gram negative cocco-bacillus that is maintained in wild reservoirs. Maintenance of the organism in the wild is primarily through a cycle of infection between small mammals such as rodents and hemaphagous fleas, although it may also be transmitted by direct contact or ingestion of infected animals [1, 2]. While in the past, Y. pestis has caused large pandemics that have altered the course of human history, at present, there are approximately 1000–5000 cases of human plague reported worldwide annually [3]. Human cases of plague have mostly been identified as sylvatic plague that is caused as a result of direct contact with wild animals [4–8]. Pockets of plague continue to exist world-wide, including southwestern U.S., parts of Africa and Asia [3].

Efforts to develop an effective vaccine against plague have been attempted for over a century. Killed whole cell vaccines were used since late 19th century and did have some efficacy in preventing bubonic plague but were ineffective against pneumonic form of plague [9, 10]. A number of live-attenuated forms of vaccine have been shown to protect various animal models against certain forms of plague [10–14]. Unfortunately, some of these strains are not fully attenuated, limiting their ability to use for human vaccination. A more promising approach involves using sub-unit proteins of Yersinia with immunogenic and protective properties to be used as potential vaccine candidates [15–18]. Currently, among the most promising vaccine candidates include two virulence factors of Yersinia, F1 and LcrV (or V), which have been studied individually and in combination and generate strong immunogenic responses in mice as well as humans [15, 19–26]. F1 is a 15.5 kDa proteinaceous capsule which protects Yersinia from phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils [27]. LcrV forms the tip of Yersinia type III secretion system (TTSS) apparatus and is involved in secretion and translocation of effectors into eukaryotic cells [28]. Passive immunization with anti F1-antibodies or anti-LcrV antibodies protects against Y. pestis [29–31], suggesting that the mechanism of protection by active vaccination is largely provided by the humoral immune response.

Because the numbers of human cases are sporadic and small, diagnosis and treatment are frequently delayed leading to an increased chance of morbidity and mortality. Strategies for mass vaccination or prophylaxis of people in endemic areas are not practical or cost effective due to the small numbers of cases that would be prevented. Also, since humans are a “dead-end” host in that they would not participate in maintenance of the enzootic cycle, vaccination of humans would not affect the maintenance of the reservoir and endemicity of the bacteria.

One attractive strategy for management of zoonotic diseases is the interruption of the infectious cycle in the reservoir or (where applicable) the vector. Vector interruption strategies have been used with great success against several pathogens including eradication of malaria from North America [32]. Previous works have shown that vaccination of wild reservoirs has been successful in the eradication of rabies virus from endemic regions around the world [33–40]. There, a recombinant vaccinia virus (VV) was constructed to express the rabies virus glycoprotein and distributed to foxes, skunks and raccoons through oral baits [33, 34]. VV is an attractive vehicle to introduce antigens for several reasons. Due to its use as an environmentally released rabies vaccine, a large body of information about VV’s infectivity and safety for multiple animal species has been accumulated. Importantly, it is not known to be spread from animal to animal, which minimizes its risk in an environmental release.

Here, we report our studies on the development of a vaccinia virus based reservoir-targeted vaccine against Y. pestis.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Viral, bacterial and mouse strains

VV strain vRB12, which is a mouse adapted WR strain of VV with a deletion of vp37 gene, was a kind gift of Dr. Bernard Moss (National Institute of Health)[41]. VV was maintained by growing in HeLa cells as described [42].

Y. pestis strain KIM D27 (Y. pestis Δpgm) was used for challenge experiments of vaccinated and control vaccinated mice. This is a pigmentation negative strain that has a 102-Kb deletion in the pigmentation (pgm) locus resulting in attenuation of Y. pestis when administered via subcutaneous route [7]. Plasmid pCD1 of Y. pestis was used for amplification of LcrV (or V) [43]. C57BL/6 male mice, 6–8 weeks old, were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Boston, MA).

2.2. Construction of VV-F1-V

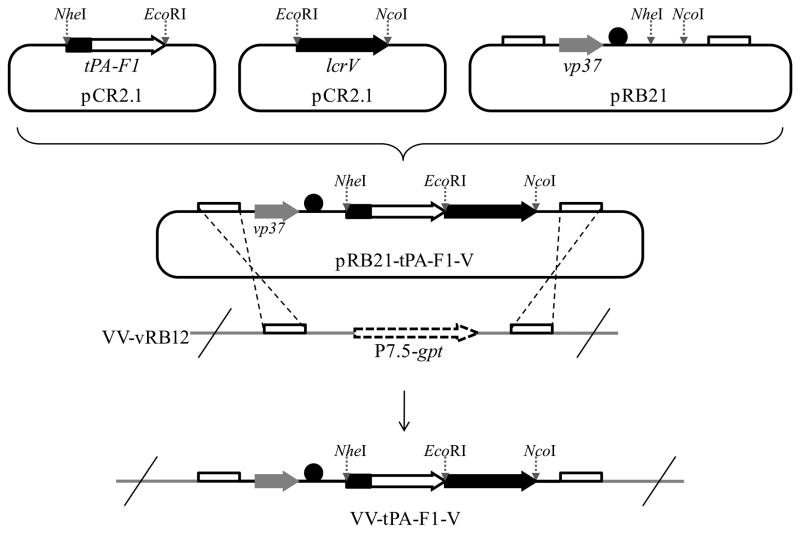

The F1 gene was amplified from DNA purified from Y. pestis Δpgm using primers caf1-F and caf1-R (Table 1). The V gene was amplified from plasmid pCD1 of Y. pestis using primers LcrV-F and LcrV-R (Table 1). A tissue plasminogen signal sequence was added upstream of F1 fragment by series of PCRs using specific overlapping primers, namely caf1 TPAovrlp and caf1 TPAovrlp2 (Table 1). The TPA-F1 and V products were cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Figure 1). Clones containing appropriate insert were selected and confirmed by sequencing at the Tufts University Sequencing Facility. TPA-F1 and V DNA were purified from the selected clones using QiaPrep Spin Column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The TPA-F1 DNA was digested using NheI and EcoRI, while V DNA was digested with EcoRI and NcoI. The TPA-F1 and V restricted fragments were gel purified using Qiaquick column (Qiagen) and fused by PCR using specific overlapping primers (Table 1). The two fragments were separated by an EcoRI restriction site. The fused TPA-F1-V DNA was cloned into pCR2.1 and appropriate clones with the insert were selected and sequenced to verify that the sequence was correct. The TPA-F1-V DNA was digested with NheI and NcoI. The restricted fragment was ligated to NheI and NcoI digested viral vector pRB21 (kind gift of Dr. Bernard Moss) to form pRB21-TPA-F1-V. The plasmid was transfected into E. coli TOP10 cells [44]. Appropriate clones containing the correct insert were selected by restriction mapping and DNA sequencing.

Table 1.

Primers used in generation and characterization of VV-F1-V

| Primer name | Sequence (5′ – 3′) | Function |

|---|---|---|

| caf1-F | ATGAAAAAAATCAGTTCCGTTATC | Forward primer for F1 |

| caf1-R | GTAGGCTCTAATCATGAATTCTTGGTTAGATACGGTTAC | Reverse primer for F1 with LcrV overhang and EcoR1 in between |

| caf1 TPAovrlp | GCTTTCCCATTGCCTGACCAGGGAATACATGGGAGGTTCAGAAGAATGAAAAAAATCAGTTCCGTTATC | Partial addition of TPA signal sequence |

| caf1 TPAovrlp2 | GCTAGCATGAAGAGAGAGCTGCTGTGTGTACTGCTGCTTTGTGGACTGGCTTTCCCATTGCCTGACCAG | Partial addition of TPA signal sequence |

| LcrV-F | ACCGTATCTAACCAAGAATTCATGATTAGAGCCTACGAACAA | Forward primer for LcrV with F1 overhang and EcoR1 in between |

| LcrV-R | CCATGGTCATTTACCAGACGTGTCAT | Reverse primer for LcrV |

| cafLcrVInt-F | TCAGGATGGAAATAACCACCA | Internal forward primer for F1-V detection in rVV |

| cafLcrVInt-R | ATGCATTACTGCCATGAACG | Internal reverse primer for F1-V detection in rVV |

| vRB12Int-F | TTTTAGCGATATAGCCGATGA | Forward primer to detect presence of vRB12 |

| vRB12Int-R | GATGAAGCCTTCGCCATC | Reverse primer to detect presence of vRB12 |

Figure 1.

Strategy to construct VV-F1-V. F1 (white arrow) and LcrV (black arrow) were amplified and cloned into pCR2.1 at specific restriction sites (marked by dotted gray arrows). A tPA signal sequence (black rectangle) was added to the 5′-end of F1 fragment. The tPA-F1 and LcrV fragments were fused by overlap PCR and ligated into vaccinia virus cloning vector, pRB21. Plasmid pRB21 has a vaccinia virus promoter (black circle), vp37 gene (gray arrow) for selection of recombinants, and VV homologous sites (white box) for recombination with VV-vRB12. pRB21 carrying tPA-F1-V was transfected into VV-vRB12 infected CV-1 cells. Double homologous cross over results in formation of recombinant virus, VV-tPA-F1-V (or VV-F1-V). The recombinant virus gains a copy of vp37 gene during crossing-over event which is essential for plague formation, the feature used for recombinant selection. The purity of recombinants was tested by amplifying gpt sequence (dotted white arrow) (PCR data not shown), which is present only in VV-vRB12 and is lost during recombinant formation.

The recombinant vaccinia virus was generated by transfecting pRB21-TPA-F1-V into infected cells as described [41], with the exception that Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used for transfection as per the manufacturer’s instructions in place of CaCl2. Briefly, confluent CV-1 cells (American Tissue Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were infected with VV vRB12 for 2 h at 37°C. 10 μl of Lipofectamine reagent was added to 500 μl of serum-free MEM. 5 μg of pRB21-TPA-F1-V DNA was added to prediluted Lipofectamine reagent and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. After removing the viral inoculum from CV-1 cells, the DNA-Lipofectamine mix was added to the monolayer and incubated at 37°C for 30min. After 30 min, MEM supplemented with 2.5% FBS (MEM-2.5) was added and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. After 3 h, the media was replaced with fresh MEM-2.5 and incubated overnight at 37°C. The cells were then collected and prepared for neutral red plaque selection.

Recombinant virus was selected using neutral red plaque selection assay as described previously [41]. Four rounds of plaque selection assay were performed to ensure isolation of purified recombinant virus.

The recombinant virus was maintained and amplified by infecting HeLa cells. The virus titer was determined using crystal violet staining as described previously [45].

The presence of TPA-F1-V insert in recombinant VV was analyzed by PCR at an annealing temperature of 55°C using primers specific to F1-V insert, namely cafLcrVInt-F and cafLcrVInt-R (Table 1). To determine presence of any unrecombined vRB12 contaminating the final selection, a PCR was performed using primers specific to E. coli gpt segment (vRB12Int-F and vRB12Int-R, Table 1) at an annealing temperature of 54°C. The E. coli gpt segment present in vRB12 is lost during the recombination event to form virus containing the insert.

2.3. Western Blotting

The expression of F1-V fusion protein by recombinant VV was analyzed by western blotting. Briefly, a whole cell lysate of infected HeLa cells was obtained as previously described [45]. After lysis, the cell debris was removed by spinning cells at slow speed (300 X g). The supernatant samples were collected and separated on 10% SDS-PAGE followed by transfer of separated proteins on to a polyvinyldifluoride (Immobilon-P) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Western blotting was performed as previously described [45], with the exception of an anti-LcrV primary antibody used at a dilution of 1:15,000.

2.4. Mouse vaccination and Determination of antibody response

Cohorts of C57BL/6 male mice were infected by gavage with a dose of 107 or 108 plaque-forming units (pfu) of VV-F1-V. Cohorts of control C57BL/6 male mice were infected with 108 pfu of VV carrying a non-specific insert (VV-ospA) [45]. The antibody response in all mice was analyzed by western blotting and ELISA of mouse serum, carried out at weekly time intervals. Mouse sera were collected by tail-vein bleeding and antibody response was determined against purified GST-LcrV protein.

2.5. ELISA

Hi-bind 96-well plates (Costar, Corning, NY) were coated with 3μg/ml of GST-LcrV diluted in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. The GST-LcrV was removed and the plates were blocked with 1% BSA dissolved in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Serum samples were diluted in PBS. After removing the blocking reagent, the top well of each lane was loaded in duplicate with diluted serum. The samples were serially diluted in equal volume of PBS. Following overnight incubation at 4°C, the samples were aspirated and the plates were washed three times with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS. The plates were incubated with anti-mouse HRP-linked IgG secondary antibody (1:2000 dilution in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature. The secondary antibody was removed and plates were again washed as described above. Plates were incubated with SureBlue TMB peroxidase substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) for 5 min followed by addition of equal volume of TMB stop solution (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). Absorbance was measured at 450nm. Serum from unvaccinated mice were used as the negative control. The mean of absorbance values of unvaccinated mouse serum was set as cut-off. The reciprocal of highest dilution above the cut-off was defined as endpoint antibody titer of each serum sample. To minimize variability between plates, a standard sample consisting of a mixture of serum from 5 different VV-F1-V vaccinated mice that was aliquotted and frozen, was used to normalize readings. For quality control, any plates that showed variations of more than ±20% from the standards were discarded. The serum mix control was serially diluted as described above in each plate.

2.6. Mouse infections and challenge

The LD50 of Y. pestis KIM D27 in C57BL/6 mice given by intranasal route was determined. Three groups of 12 mice each were infected with doses of 2X103, 2X104 and 2X105 cfu bacteria diluted in PBS. Briefly, Y. pestis KIM D27 (Y. pestis Δpgm) was grown overnight in Heart Infusion medium (Difco) at 26°C with constant shaking. The overnight culture was diluted in the same medium to an absorbance of 0.2 at 600 nm. The diluted culture was grown as described above to an OD600 of approximately 0.8. The bacteria were diluted to selected doses in 30 μl PBS. Mice were anesthetized by isofluorane and infected intranasally with 30 μl dose of bacterial suspension. The mice were observed until moribund or 14 days post challenge, whatever comes first. The LD50 was calculated using Reed and Münch method [46, 47].

To determine protective efficacy of the vaccine, VV-F1-V- and control-vaccinated mice were challenged with a dose of 10 times LD50 of Y. pestis KIM D27 as described above. Dilutions of the bacterial inocula were plated on Heart Infusion agar to determine the actual dose administered. Three independent experiments were performed to determine the vaccine efficacy. All the procedures were reviewed and approved by the Tufts University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Kaplan and Meier survival estimates were used for data analyses of mice survival experiments. Log rank test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to calculate statistical significance between groups wherever applicable.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Expression of recombinant F1-Vprotein

vRB12, a strain of VV which has a deletion in the vp37 gene, was used for the construction of recombinant virus. vp37 encodes a 37-KDa outer envelope protein which is essential for virus packaging, egress, and plaque formation [44]. The recombinant virus gains a copy of vp37 gene during crossing over with pRB21-tPA-F1-V, thus permitting selection of recombinants by plaque formation (Figure 1). A TPA signal sequence was added to the vaccine construct to target the recombinant protein for export and improve antibody production [48].

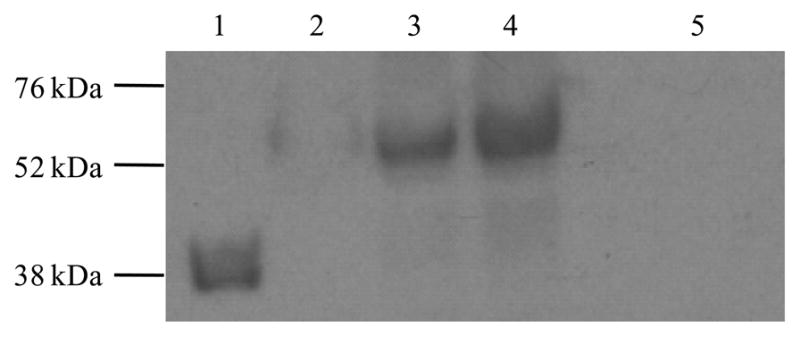

After construction and selection, confirmation that the selected viral clone contained the insert and expressed the F1-V fusion protein was performed by PCR (data not shown) and by western blotting (Figure 2). PCR was also performed using primers specific for the irrelevant gpt insert that is lost during recombination to determine purity of the final virus (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Expression of F1-V fusion protein by recombinant virus in vitro. Confluent Hela cells were infected with VV-F1-V. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and probed with an antibody to LcrV to test for expression of F1-V fusion protein. Lane 1: Positive control, Yersinia lysate (expressing only LcrV); Lanes 2, 3 and 4 were loaded with VV-F1-V infected cell lysate in increasing 5-fold increments; Lane 5: Negative control, cell lysate infected by a non-specific strain of VV (VV-CD56) which lacks F1-V insert. The predicted sizes of LcrV and F1-V are 37 kDa and 53 kDa respectively.

3.2. Antibody response to VV-F1-V

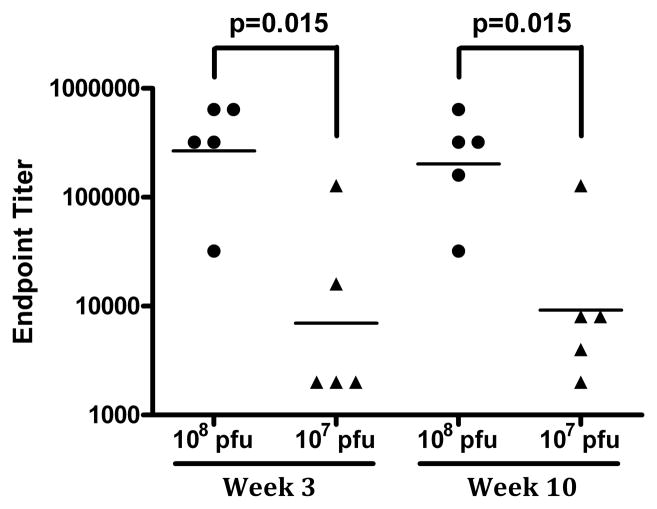

We next determined whether vaccination of miceVV-F1-V virus resulted in antibody responses to LcrV. C57BL/6 mice were infected with 107 or 108 pfu of VV-F1-V by oral gavage. These doses were selected based on our experience with a previous VV-based vaccine [45]. Collected blood samples were analyzed at week 3 and week 10 post-inoculation and antibody titer to LcrV was determined by endpoint ELISA. We observed a dose-dependent antibody response to the vaccine (Figure 3). Mice immunized with 108 pfu vaccine had antibody responses that were more than 10 fold higher than mice vaccinated with 107 pfu of the vaccine (Figure 3). The difference in antibody response between the two doses was maintained throughout the course of observation and the levels of antibody remained constant over this period.

Figure 3.

Dose-dependent antibody response in VV-F1-V vaccinated mice. C57BL/6 mice were administered either 107 (triangle) or 108 (circle) pfu of VV-F1-V by oral gavage. Antibody response in serum obtained at weeks 3 and 10 post-vaccination are shown. Each data point represents antibody titer for one mouse. Black bars represent the geometric mean of antibody response for each group. The difference in antibody titers between the two dosage groups was significant (p<0.05) by Mann-Whitney U test.

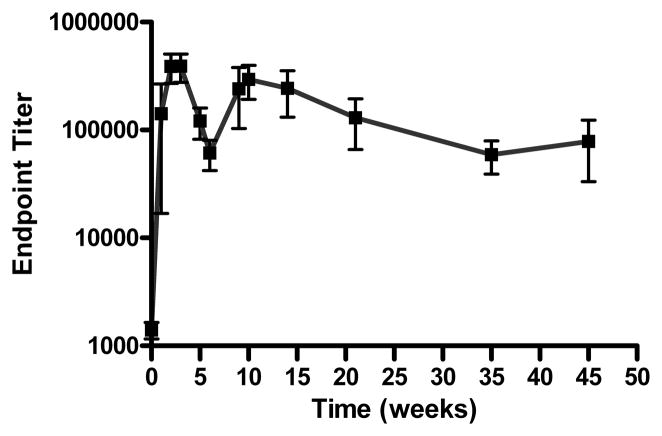

3.3. Kinetics of antibody development

We next assessed the timing of development and the stability of the antibody response after vaccination withVV-F1-V. Mice immunized with 108 pfu of VV-F1-V developed an antibody response within 7 days post-vaccination and reached a peak titer by week 3 (Figure 4). The antibody titers peaked at dilution of approximately 1:256,000. The antibody response generated with a single dose of 108 pfu of recombinant virus was stable for at least 45 weeks (the end of the observation period).

Figure 4.

Kinetics of antibody response against VV-F1-V. C57BL/6 mice were vaccinated with 108 pfu of VV-F1-V. Serum antibody response against LcrV was measured at various time points by endpoint dilutional titering. Each square represents the mean antibody titer for at least 3 mice. Error bars represent standard deviation.

The kinetics of the antibody response in mice administered 107 pfu of vaccine appeared to be similar, but a lower titer was attained. Antibody titers remained stable for the 10 weeks these mice were followed (Figure 3).

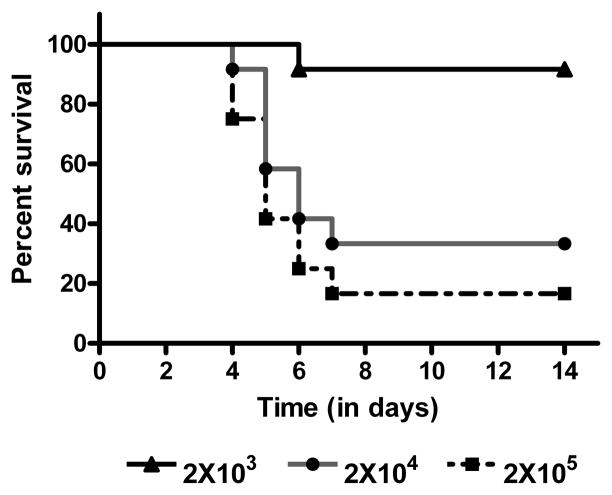

3.4. Efficacy of VV-F1-V vaccine

To determine the protective efficacy of the vaccine, we utilized a mouse intranasal infection model [49]. Y. pestis strain KIM D27 is an attenuated strain that is lacking the pgm gene. Administered intranasally, it has been shown to result in lethality to mice. The LD50 of Y. pestis KIM D27 in C57BL/6 males by intranasal route of inoculation was determined as 1.6 X 104 cfu (Figure 5). A dose of 2X105 cfu was used in all subsequent challenge experiments.

Figure 5.

Determination of LD50 of Y. pestis KIM D27 in C57BL/6 mice by intranasal route of inoculation. Three groups of mice (n=12 in each group) were given 2X103, 2X104, or 2X105 cfu of Y. pestis KIM D27 by intranasal inoculation. Survival rate of the groups of mice was determined over a period of 14 days. The method of Reed and Münch was used to calculate the LD50 dose [47].

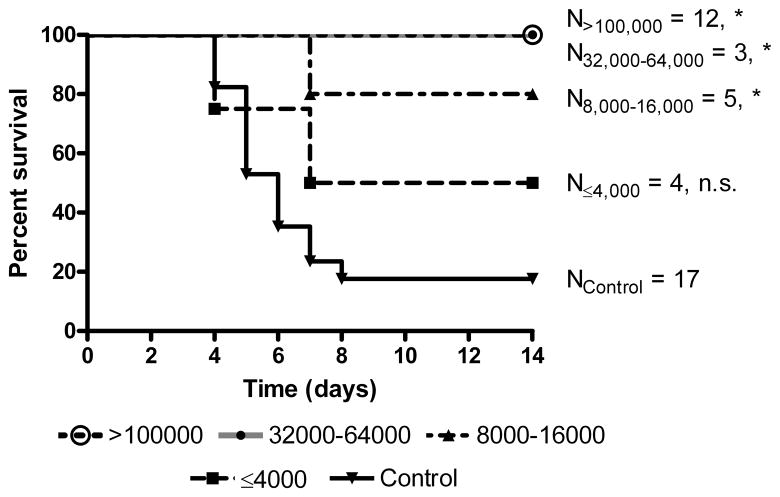

To determine the efficacy of VV-F1-V vaccine, groups of mice were immunized with various doses of the vaccine to generate a range of antibody responses. A control cohort of mice was immunized with 108 pfu of a VV expressing an irrelevant protein, the outer surface protein A of Borrelia burgdorferi (VV-ospA) [45]. Antibody titers in mice were determined by ELISA four weeks post-vaccination. At week 5 post-vaccination, mice were challenged by intranasal administration of Y. pestis KIM D27. We observed titer-dependent protection against challenge of Y. pestis KIM D27 (Figure 6). Our data show that mice with titers >100,000 (n=12) were fully protected as compared to the control vaccinated mice (n=17) which had a percentage survival of less than 20%. Despite our efforts to generate a diversity of antibody titers, there were fewer mice with antibody titers between 8,000–64,000. Although both groups (N8,000–16,000 and N32,000–64,000) were statistically significantly different from control, the smaller numbers of mice in these groups does not allow us to precisely determine the efficacy of protection at these titers.

Figure 6.

Protective efficacy of VV-F1-V vaccine in mice. C57BL/6 mice were vaccinated with differing amounts of VV-F1-V to generate a diversity of antibody titers. VV-F1-V or control vaccinated mice were administered with a dose of 10XLD50 of Y. pestis KIM D27 by intranasal inoculation at 5 weeks post-vaccination. Three independent experiments were performed (n=3). The survival rates of mice with differing antibody titers from the three experiments are shown. Log-rank test was performed to determine the significance by comparing survival percentage of each titer group to the control vaccinated mice. ‘N’ represents number of mice in each titer group, and asterisks indicate statistical significance obtained by log rank test. The ‘p’ values obtained by log rank test are as follows: For titers>100000 vs. control, p<0.0001; for titers between 32000–64000 vs. control, p=0.02; for titers between 8000–16000 vs. control, p=0.01; for titers less than ≤ 4000 vs. control the difference was not significant (n.s).

3.5. Durability of protection by VV-F1-V

We next sought to determine window of protection conferred by a single dose of VV-F1-V. For this purpose, two groups of mice were vaccinated with 108 pfu of VV-F1-V. One group was challenged on week 5 post-vaccination as earlier described. The other group was challenged 45 weeks post-vaccination. One hundred percent of vaccinated mice challenged either 5 weeks or 45 after vaccination survived (data not shown). This was not unexpected given that all mice in both groups had antibody titers that were greater than 1:32,000, the level at which 100% protection is seen in mice challenged earlier after vaccination.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we have developed an oral vaccine that would be suitable for deployment targeting the zoonotic reservoir of Y. pestis. Expression of the Y. pestis F1 and V antigens as a fusion protein from vaccinia virus administered orally generates long lasting antibody responses after a single dose and protects mice against lethal Y. pestis infection after intranasal challenge up to 100%. Based on studies with F1-V showing good correlation between the intranasal models and subcutaneous models using wild-type Y. pestis [49], it is likely that this vaccine would also protect against subcutaneous challenge with Y. pestis. The long term stability of the antigenic response observed with our vaccine appears to be a characteristic of the F1-V fusion antigen as antibody responses to other vaccinia virus expressed proteins in mice has not been as long-lived [45]. In studies of intramuscular vaccination, administration of the F1-V fusion protein produced strong antibody response in black-footed ferrets for up to 2 years after two doses [50].

Although our data are promising, there are some caveats to our results. Although intranasal inoculation is an effective delivery mechanism, it does not faithfully reproduce infection introduced by the feeding of infected fleas. Other studies comparing protection arising from F1-V antigens after flea infection have shown a good correlation with intranasal challenge, so we anticipate that protection will be good with the vaccinia virus based oral vaccine [51]. Nonetheless this clearly will require further testing with a fully virulent strain and natural delivery through infected fleas. Second, although we have shown excellent protection with the vaccinia virus expressed F1-V fusion protein, we have not tested the relative contributions of the two components. Theoretically, the combination of both antigens would provide protection against naturally occurring variants at these two loci. Capsule (F1) deficient Y. pestis do occur in the wild as small minority of wild isolates and has potential to cause disease [52]. Others have shown that the F1-V fusion protein protects against F1− strain of Y. pestis to the same extent as observed with vaccination by LcrV alone [49]. Similarly, there have been reports of two variant populations of Y. pestis based on variations in LcrV sequence, designated as V-O:3 and V-Yp [53, 54]. While V-O:3 is expressed by Y. pestis serotype O:3 as well as by few non-pestis strains of Yersinia, V-Yp is primarily expressed by Y. pestis alone [53, 54]. Protection by V-antisera is possible only if the immunizing V-Ag sequence is same as carried by the challenge strain of Y. pestis [53, 54]. The prevalence of LcrV variants in wild populations of Y. pestis is not known and whether antibodies to F1 will provide sufficient protection for strains that express variant LcrV is also not known.

There are multiple hurdles to be considered in the development of a reservoir targeted vaccine. Although the use of a live, replicating viral vector allows for oral administration that results in high antibody titers, primary consideration must be for the concern for human contact with the vaccine and the potential for accidental infection. The current experience with vaccinia virus based reservoir targeted vaccines has been excellent to date. Over 75 million doses of the Raboral vaccine for rabies prevention that targets raccoons and foxes have been distributed in Europe and the U.S. [55, 56]. To date, there have been two reports of human infection resulting from contact with the vaccine [57, 58]. In both cases, inoculation of the virus resulted from removal of the vaccine-laden bait from a pet dog. Both case patients had some degree of immunosuppression (pregnancy in one case and immunosuppressive medications for inflammatory bowel disease in the other). Both cases resulted in the development of skin lesions of vaccinia infection with one patient undergoing excision and drainage of a suspected abscess.

Other concerns about a reservoir targeted strategy include its effects on non-target species and the potential for recombination with other circulating pox viruses. As part of the approval process for the vaccinia virus based rabies vaccine, vaccinia virus has been tested in multiple “non-target” species [56]. Although vaccinia virus is capable of infecting a wide range of species, no long-term detrimental effects were seen on any of the tested species [56]. The occurrence of horizontal gene transfer between vaccinia virus and other Orthopox viruses has been documented in the laboratory. Genetic recombination occurs between viruses of the same genus but not between separate genera [59]. No evidence of recombination with endogenous viruses has been shown with distribution of Raboral. There is no known wild reservoir of orthopox viruses of the same genus as vaccinia virus circulating in the U.S. although in various parts of Europe, related cowpox viruses are found in bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) and wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) [60–63].

A similar vaccine for reservoir targeted vaccination against Y. pestis using raccoonpox as a delivery system has previously been reported [64]. The F1-V antigen delivered using a raccoonpox viral vector is protective against infection with Y. pestis delivered by intramuscular injections [64]. The use of raccoonpox as a delivery vector has some potential advantages and disadvantages compared with the use of vaccinia virus. One potential advantage to raccoonpox is that it may be less infectious for humans, although this has not been studied in a systematic way. There has been a single report of a laboratory worker that was accidentally inoculated with raccoonpox that had a very mild, self-limited disease [65]. Among the disadvantages are that, in contrast to vaccinia virus, there is no experience with raccoonpox in environmental releases to determine its safety profile both for target and non-target animals. Raccoonpox is endemic in North America. Although originally isolated from raccoons, the true reservoir remains uncertain and the rates of infection in animals that would be target species for a Y. pestis vaccine (e.g. prairie dogs, other small rodents) is unknown. The prevalence of prior infection could affect safety and efficacy of the vaccine in several ways. First, the presence of a circulating wild virus increases the risk of recombination and loss of control of the vaccine. Although a replicating vaccine that could be passed between animals would be advantageous for penetration of a vaccine into a susceptible population, the ability of the vaccine to replicate, spread and potentially recombine would pose risks to our ability to control damage should the vaccine have unanticipated adverse effects. Vaccinia virus does not transmit from animal to animal and is reportedly shed for only 48 hrs after ingestion of Raboral vaccine by raccoons and foxes [66]. Thus, cessation of bait deployment of a vaccinia virus vaccine should be sufficient to halt wild transmission.

The second issue is that prior infection with raccoonpox may inhibit the development of a protective response to a raccoonpox based vaccine. This disadvantage may not be limited to raccoonpox as prior infection with raccoonpox may affect responses to the vaccinia virus based rabies vaccine [67]. However, this is likely to be less of an issue with poxviruses from different genera and we have found that re-infection can occur with mice administered vaccinia virus vaccine [45].

Despite the small incidence of human disease, targeting of Y. pestis is valuable because of the severity of the infection. However, the relative paucity of human cases suggests that antigens targeting Y. pestis may be best included as part of a vaccine “cocktail” that targets multiple human diseases that utilize the same reservoir to improve the cost/benefit ratio of vaccine deployment. Because vaccinia virus is relatively large and can accommodate multiple inserts, it is an ideal vector for which to pursue a multi-target reservoir vaccine strategy. Raccoons and foxes that are targeted by the vaccinia virus based rabies vaccine are relatively rarely infected with Y. pestis and prairie dogs and woodchucks are only rarely infected by rabies. However, antigens that would protect against Hantavirus, Babesia, Anaplasma/Ehrlichia, Borrelia or their vectors would be ideal for inclusion in a combined vaccine. Future studies will be needed to determine the efficacy of such combination vaccines and design of strategies to deploy reservoir targeted vaccines.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Mekki Bensaci, Dr. Tanja Petnicki-Ocwieja, Dr. Elizabeth Tenorio and Meghan Marre for their helpful discussions. This project was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases R41AI078631 (L.T.H.) and R01AI068799 (L.T.H.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gage KL, editor. Plague. 9. London: Arnold; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gage KL, Kosoy MY. Natural history of plague: perspectives from more than a century of research. Annu Rev Entomol. 2005;50:505–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stenseth NC, Atshabar BB, Begon M, Belmain SR, Bertherat E, Carniel E, et al. Plague: past, present, and future. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christie AB. Plague: review of ecology. Ecol Dis. 1982;1(2–3):111–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craven RB, Maupin GO, Beard ML, Quan TJ, Barnes AM. Reported cases of human plague infections in the United States, 1970–1991. J Med Entomol. 1993;30(4):758–61. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/30.4.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gage KL, SEL, Dennis DT, Montenieri JA. Human plague in the United States: a review of cases from 1988–1992 with comments on the likelihood of increased plague. Border Epidemiol Bull. 1992;19:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry RD, Fetherston JD. Yersinia pestis--etiologic agent of plague. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10(1):35–66. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velimirovic B. Plague and Glasnost. First information about human cases in the USSR in 1989 and 1990. Infection. 1990;18(6):388–93. doi: 10.1007/BF01646417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavanaugh DC, Elisberg BL, Llewellyn CH, Marshall JD, Jr, Rust JH, Jr, Williams JE, et al. Plague immunization. V. Indirect evidence for the efficacy of plague vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1974;129(Suppl):S37–40. doi: 10.1093/infdis/129.supplement_1.s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Titball RW, Williamson ED. Vaccination against bubonic and pneumonic plague. Vaccine. 2001;19(30):4175–84. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oyston PC, Russell P, Williamson ED, Titball RW. An aroA mutant of Yersinia pestis is attenuated in guinea-pigs, but virulent in mice. Microbiology. 1996;142 ( Pt 7):1847–53. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson VL, Oyston PC, Titball RW. A dam mutant of Yersinia pestis is attenuated and induces protection against plague. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;252(2):251–6. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell P, Eley SM, Hibbs SE, Manchee RJ, Stagg AJ, Titball RW. A comparison of Plague vaccine, USP and EV76 vaccine induced protection against Yersinia pestis in a murine model. Vaccine. 1995;13(16):1551–6. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00090-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor VL, Titball RW, Oyston PC. Oral immunization with a dam mutant of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis protects against plague. Microbiology. 2005;151(Pt 6):1919–26. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27959-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrews GP, Heath DG, Anderson GW, Jr, Welkos SL, Friedlander AM. Fraction 1 capsular antigen (F1) purification from Yersinia pestis CO92 and from an Escherichia coli recombinant strain and efficacy against lethal plague challenge. Infect Immun. 1996;64(6):2180–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2180-2187.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews GP, Strachan ST, Benner GE, Sample AK, Anderson GW, Jr, Adamovicz JJ, et al. Protective efficacy of recombinant Yersinia outer proteins against bubonic plague caused by encapsulated and nonencapsulated Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 1999;67(3):1533–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1533-1537.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matson JS, Durick KA, Bradley DS, Nilles ML. Immunization of mice with YscF provides protection from Yersinia pestis infections. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson ED, Eley SM, Griffin KF, Green M, Russell P, Leary SE, et al. A new improved sub-unit vaccine for plague: the basis of protection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995;12(3–4):223–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson GW, Jr, Leary SE, Williamson ED, Titball RW, Welkos SL, Worsham PL, et al. Recombinant V antigen protects mice against pneumonic and bubonic plague caused by F1-capsule-positive and -negative strains of Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 1996;64(11):4580–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4580-4585.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu WT, Hsu HL, Liang CC, Chuang CC, Lin HC, Liu YT. A comparison of immunogenicity and protective immunity against experimental plague by intranasal and/or combined with oral immunization of mice with attenuated Salmonella serovar Typhimurium expressing secreted Yersinia pestis F1 and V antigen. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;51(1):58–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller J, Williamson ED, Lakey JH, Pearce MJ, Jones SM, Titball RW. Macromolecular organisation of recombinant Yersinia pestis F1 antigen and the effect of structure on immunogenicity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;21(3):213–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Titball RW, Howells AM, Oyston PC, Williamson ED. Expression of the Yersinia pestis capsular antigen (F1 antigen) on the surface of an aroA mutant of Salmonella typhimurium induces high levels of protection against plague. Infect Immun. 1997;65(5):1926–30. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1926-1930.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williamson ED. Plague vaccine research and development. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;91(4):606–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williamson ED, Eley SM, Stagg AJ, Green M, Russell P, Titball RW. A single dose sub-unit vaccine protects against pneumonic plague. Vaccine. 2000;19(4–5):566–71. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williamson ED, Flick-Smith HC, Lebutt C, Rowland CA, Jones SM, Waters EL, et al. Human immune response to a plague vaccine comprising recombinant F1 and V antigens. Infect Immun. 2005;73(6):3598–608. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3598-3608.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williamson ED, Vesey PM, Gillhespy KJ, Eley SM, Green M, Titball RW. An IgG1 titre to the F1 and V antigens correlates with protection against plague in the mouse model. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;116(1):107–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du Y, Rosqvist R, Forsberg A. Role of fraction 1 antigen of Yersinia pestis in inhibition of phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 2002;70(3):1453–60. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1453-1460.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller CA, Broz P, Cornelis GR. The type III secretion system tip complex and translocon. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68(5):1085–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson GW, Jr, Worsham PL, Bolt CR, Andrews GP, Welkos SL, Friedlander AM, et al. Protection of mice from fatal bubonic and pneumonic plague by passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies against the F1 protein of Yersinia pestis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56(4):471–3. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motin VL, Nakajima R, Smirnov GB, Brubaker RR. Passive immunity to yersiniae mediated by anti-recombinant V antigen and protein A-V antigen fusion peptide. Infect Immun. 1994;62(10):4192–201. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4192-4201.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato K, Nakajima R, Hara F, Une T, Osada Y. Preparation of monoclonal antibody to V antigen from Yersinia pestis. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1991;12:225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klempner MS, Unnasch TR, Hu LT. Taking a bite out of vector-transmitted infectious diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(25):2567–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brochier B, Blancou J, Thomas I, Languet B, Artois M, Kieny MP, et al. Use of recombinant vaccinia-rabies glycoprotein virus for oral vaccination of wildlife against rabies: innocuity to several non-target bait consuming species. J Wildl Dis. 1989;25(4):540–7. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-25.4.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brochier B, Kieny MP, Costy F, Coppens P, Bauduin B, Lecocq JP, et al. Large-scale eradication of rabies using recombinant vaccinia-rabies vaccine. Nature. 1991;354(6354):520–2. doi: 10.1038/354520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laine M, Niin E, Partel A. The rabies elimination programme in Estonia using oral rabies vaccination of wildlife: preliminary results. Dev Biol (Basel) 2008;131:239–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matouch O, Vitasek J, Semerad Z, Malena M. Rabies-free status of the Czech Republic after 15 years of oral vaccination. Rev Sci Tech. 2007;26(3):577–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosatte RC, Donovan D, Davies JC, Allan M, Bachmann P, Stevenson B, et al. Aerial distribution of ONRAB baits as a tactic to control rabies in raccoons and striped skunks in Ontario, Canada. J Wildl Dis. 2009;45(2):363–74. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-45.2.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosatte R, Allan M, Bachmann P, Sobey K, Donovan D, Davies JC, et al. Prevalence of tetracycline and rabies virus antibody in raccoons, skunks, and foxes following aerial distribution of V-RG baits to control raccoon rabies in Ontario, Canada. J Wildl Dis. 2008;44(4):946–64. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-44.4.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hostnik P, Toplak I, Barlic-Maganja D, Grom J, Bidovec A. Control of rabies in Slovenia. J Wildl Dis. 2006;42(2):459–65. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-42.2.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sidwa TJ, Wilson PJ, Moore GM, Oertli EH, Hicks BN, Rohde RE, et al. Evaluation of oral rabies vaccination programs for control of rabies epizootics in coyotes and gray foxes: 1995–2003. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227(5):785–92. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.227.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moss B, editor. Expression of proteins in mammalian cells using vaccinia viral vectors. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lahteenmaki K, Virkola R, Saren A, Emody L, Korhonen TK. Expression of plasminogen activator pla of Yersinia pestis enhances bacterial attachment to the mammalian extracellular matrix. Infect Immun. 1998;66(12):5755–62. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5755-5762.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perry RD, Straley SC, Fetherston JD, Rose DJ, Gregor J, Blattner FR. DNA sequencing and analysis of the low-Ca2+-response plasmid pCD1 of Yersinia pestis KIM5. Infect Immun. 1998;66(10):4611–23. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4611-4623.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blasco R, Moss B. Selection of recombinant vaccinia viruses on the basis of plaque formation. Gene. 1995;158(2):157–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00149-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scheckelhoff MR, Telford SR, Hu LT. Protective efficacy of an oral vaccine to reduce carriage of Borrelia burgdorferi (strain N40) in mouse and tick reservoirs. Vaccine. 2006;24(11):1949–57. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Welkos S, O’Brien A. Determination of median lethal and infectious doses in animal model systems. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:29–39. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reed LJ, Münch H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. The American Journal of Hygiene. 1938;27(3):5. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gipson CL, Davis NL, Johnston RE, de Silva AM. Evaluation of Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis (VEE) replicon-based Outer surface protein A (OspA) vaccines in a tick challenge mouse model of Lyme disease. Vaccine. 2003;21(25–26):3875–84. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heath DG, Anderson GW, Jr, Mauro JM, Welkos SL, Andrews GP, Adamovicz J, et al. Protection against experimental bubonic and pneumonic plague by a recombinant capsular F1-V antigen fusion protein vaccine. Vaccine. 1998;16(11–12):1131–7. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)80110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rocke TE, Smith S, Marinari P, Kreeger J, Enama JT, Powell BS. Vaccination with F1-V fusion protein protects black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes) against plague upon oral challenge with Yersinia pestis. J Wildl Dis. 2008;44(1):1–7. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-44.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jarrett CO, Sebbane F, Adamovicz JJ, Andrews GP, Hinnebusch BJ. Flea-borne transmission model to evaluate vaccine efficacy against naturally acquired bubonic plague. Infect Immun. 2004;72(4):2052–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2052-2056.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friedlander AM, Welkos SL, Worsham PL, Andrews GP, Heath DG, Anderson GW, Jr, et al. Relationship between virulence and immunity as revealed in recent studies of the F1 capsule of Yersinia pestis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21 (Suppl 2):S178–81. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.supplement_2.s178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roggenkamp A, Geiger AM, Leitritz L, Kessler A, Heesemann J. Passive immunity to infection with Yersinia spp. mediated by anti-recombinant V antigen is dependent on polymorphism of V antigen. Infect Immun. 1997;65(2):446–51. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.446-451.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anisimov AP, Lindler LE, Pier GB. Intraspecific diversity of Yersinia pestis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(2):434–64. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.2.434-464.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matouch O, Vitasek J, Semerad Z, Malena M. Elimination of rabies in the Czech Republic. Dev Biol (Basel) 2006;125:141–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rupprecht CE, Hanlon CA, Slate D. Oral vaccination of wildlife against rabies: opportunities and challenges in prevention and control. Dev Biol (Basel) 2004;119:173–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Human vaccinia infection after contact with a raccoon rabies vaccine bait - Pennsylvania, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(43):1204–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rupprecht CE, Blass L, Smith K, Orciari LA, Niezgoda M, Whitfield SG, et al. Human infection due to recombinant vaccinia-rabies glycoprotein virus. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):582–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moss B. Molecular biology of poxviruses. In: Binns MM, Smith GL, editors. Recombinant Poxviruses. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1992. pp. 45–80. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Emerson GL, Li Y, Frace MA, Olsen-Rasmussen MA, Khristova ML, Govil D, et al. The phylogenetics and ecology of the orthopoxviruses endemic to North America. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Begon M, Hazel SM, Baxby D, Bown K, Cavanagh R, Chantrey J, et al. Transmission dynamics of a zoonotic pathogen within and between wildlife host species. Proc Biol Sci. 1999;266(1432):1939–45. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chantrey J, Meyer H, Baxby D, Begon M, Bown KJ, Hazel SM, et al. Cowpox: reservoir hosts and geographic range. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122(3):455–60. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899002423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hazel SM, Bennett M, Chantrey J, Bown K, Cavanagh R, Jones TR, et al. A longitudinal study of an endemic disease in its wildlife reservoir: cowpox and wild rodents. Epidemiol Infect. 2000;124(3):551–62. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899003799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rocke TE, Iams KP, Dawe S, Smith SR, Williamson JL, Heisey DM, et al. Further development of raccoon poxvirus-vectored vaccines against plague (Yersinia pestis) Vaccine. 2009;28(2):338–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rocke TE, Dein FJ, Fuchsberger M, Fox BC, Stinchcomb DT, Osorio JE. Limited infection upon human exposure to a recombinant raccoon pox vaccine vector. Vaccine. 2004;22(21–22):2757–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Omlin D. Tools for safety assessment - vaccinia-derived recombinant rabies vaccine. Swiss National Science Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Root JJ, McLean RG, Slate D, MacCarthy KA, Osorio JE. Potential effect of prior raccoonpox virus infection in raccoons on vaccinia-based rabies immunization. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]