Abstract

Plasmodium spp. parasites cause malaria in 300 to 500 million individuals each year. Disease occurs during the blood-stage of the parasite's life cycle, where the parasite is thought to replicate exclusively within erythrocytes. Infected individuals can also suffer relapses after several years, from Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale surviving in hepatocytes. Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium malariae can also persist after the original bout of infection has apparently cleared in the blood, suggesting that host cells other than erythrocytes (but not hepatocytes) may harbor these blood-stage parasites, thereby assisting their escape from host immunity. Using blood stage transgenic Plasmodium berghei-expressing GFP (PbGFP) to track parasites in host cells, we found that the parasite had a tropism for CD317+ dendritic cells. Other studies using confocal microscopy, in vitro cultures, and cell transfer studies showed that blood-stage parasites could infect, survive, and replicate within CD317+ dendritic cells, and that small numbers of these cells released parasites infectious for erythrocytes in vivo. These data have identified a unique survival strategy for blood-stage Plasmodium, which has significant implications for understanding the escape of Plasmodium spp. from immune-surveillance and for vaccine development.

Keywords: immune evasion, rodent malaria

Malaria commences when an infected female anopheline mosquito bites and deposits, up to 125 Plasmodium sporozoites under the skin of the host (1). Studies using Plasmodium berghei sporozoites, showed that a proportion will remain in the skin and infect keratinocytes (2), others are drained by the lymphatic system and are trapped in lymph nodes, and a fraction of the deposited sporozoites enter blood vessels to migrate to the liver (3). In the liver, typically between 1 and 10 sporozoites invade hepatocytes. Other studies have shown that sporozoites can invade and migrate through other cell types, including macrophages (4), Kupffer cells (5, 6), epithelial cells, and fibroblasts (7).

The sporozoites within hepatocytes develop by a process of schizogony into merozoite forms, which escape from an infected liver cell into the sinusoid lumen (8) to invade RBC. Within RBC, the merozoites then develop into “ring” trophozoites, then mature trophozoites, and finally a schizont containing up to 32 new merozoites. These schizont-infected RBC then rupture to release merozoites that are able to invade new RBCs, resulting in an increase of parasite biomass. The Plasmodium life cycle continues when some merozoites develop into the sexual parasite stages, the male and female gametocytes, which can be taken up by mosquitoes during blood meals (9).

Some Plasmodium infections, such as Plasmodium malariae (10) and Plasmodium inui (11), persist for years and sometimes for the life of the host (12), and the reasons for this are not understood. To date, the blood-stage parasites of mammalian Plasmodium spp. are thought to survive and replicate only within RBC, but it has long been suspected that they may also have another survival strategy. The blood-stage-parasite of rodent Plasmodium spp. have been observed as sacks of merozoites within macrophages and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (13). The merozoites were associated with pigment that suggests that cells ingested parasitized RBC (pRBC) as opposed to invasion of the cells by merozoites. These merozoite-associated cells were principally in the spleen, thought to be formed by either pitting or phagocytosis of parasites by macrophages (13). It is thus possible that this is a site of latency, but proof that the transfer of infection with these cells was not contaminated with infected RBC is lacking. Furthermore, blood-stage parasites have also been found inside platelets (14) but the intrathrombocytic environment did not support parasite growth or replication (15) and infectious studies were not undertaken. Finally, avian Plasmodium also has two stages in which the parasite invades nonerythrocytes: during the initial pre-erythrocytic stages of infection and later in the blood-stage (16). The infection starts when the sporozoites from the mosquito invade skin mononuclear cells where schizonts develop and release merozoites, which have three phases. These merozoites first invade mononuclear cells throughout the body, develop through schizogony, and are released to invade erythrocytes as part of the second phase. In the final phase, merozoites from erythrocytes invade many different endothelia where the parasite grows (second exo-erythrocytic stage) (16).

We originally suspected that blood stage Plasmodium spp. might reside within an unidentified cell type and be protected from immunity, when passive transfer of Plasmodia-specific antibodies into immunocompromised mice could significantly reduce but not eliminate parasites in the blood (17). We then found that CD11c+ dendritic cells (DCs) from mice infected with Plasmodium yoelii transferred an infection to naive mice unless the donor mice were treated with antimalarial drugs, suggesting that some parasites might reside within the DCs. Here we demonstrate, predominantly using a transgenic blood-stage P. berghei-expressing GFP (PbGFP) (18), that the rodent malaria parasite P. berghei can survive and replicate within CD317+ DCs and that a small percentage of these DCs release parasites that are infectious for erythrocytes on transfer to naive mice.

Results

Blood-Stage Plasmodium Has a Tropism for CD317+ DCs.

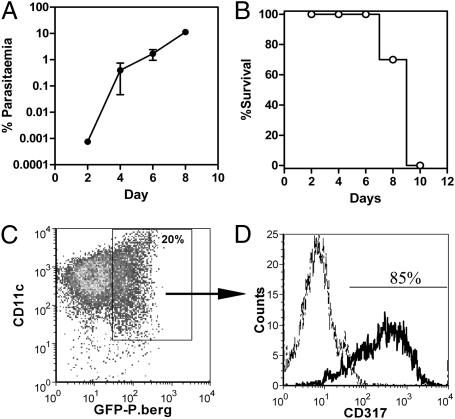

To determine if DCs could harbor P. berghei, we infected C57/B6 mice with 104 blood-stage, transgenic PbGFP (18, 19). Patent infection (first day of parasites visible on a blood smear) occurs around days 4 to 6 after inoculation (Fig. 1A), and the infection is usually lethal for mice by day 10 (Fig. 1B). Because mouse DCs are characterized by expression of CD11c (20), total CD11c+ DCs were isolated from the spleen and from blood of infected mice, following depletion of most major cell types, for studies by flow cytometry. After 7 d in multiple experiments, >20% of spleen CD11c+ DCs contained GFP (Fig. 1C) and >85% of CD11c+GFP+ DCs also expressed CD317 (Fig. 1D), labeled by monoclonal antibodies PDCA-1 and 120G8 (21). Further characterization of the GFP+CD317+CD11c+ DCs found variable expression of other DC-associated markers (B220, Ly6G, Siglec-H, F4/80, Dec205, and CD8) (Fig. S1A). Data for DCs from naive mice are provided for contrast (Fig. S1B). Approximately 40% (range of 20–70%) of CD317+ DCs of the spleen contained GFP compared with <10% of CD317− DC subpopulations by day 7 postinfection (Fig. S1C). Absolute numbers of CD317+ DCs were also significantly increased by day 7 (Fig. S1D). All GFP+CD11c+ DCs were “hypermature,” as defined by high-level expression of MHC Class II, CD80, and CD86 (Fig. S1E). In contrast with the >20% of CD11c+ splenic cells, only ∼1% of CD11c+ DC in the peripheral blood contained GFP (Fig. S1F).

Fig. 1.

Plasmodium has a tropism for CD317+ DCs. Groups of mice were infected with P. berghei that expresses the reporter protein GFP (PbGFP) and monitored for (A) parasitemia (Mean ± SEM, n = 11) and (B) survival (n = 11) in multiple experiments. DCs were isolated from the spleens of infected mice after 7 d and labeled to show expression of (C) CD11c and (D) CD317 by flow cytometry. The density plot shows uptake of PbGFP by CD11c+ DCs and the histogram shows CD317 (thick line) expression on GFP+CD11c+ DCs compared with labeling by isotype control antibody (dotted line). Data are representative of multiple independent experiments that had similar results.

Blood-Stage Plasmodium Replicates Within CD317+ DCs.

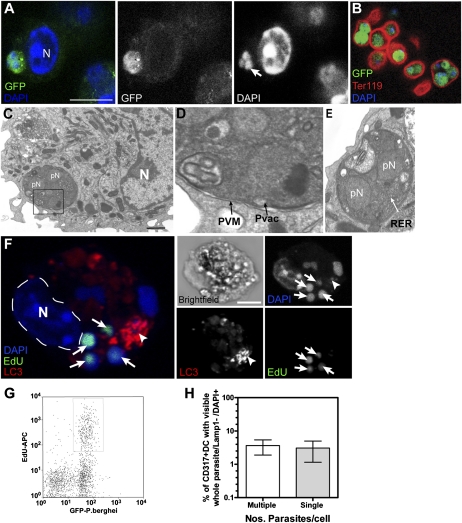

To determine if the GFP seen in DCs represented pRBC, CD317+ DCs were isolated from PbGFP-infected mice, stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, which binds DNA), and analyzed by microscopy (Fig. 2). Multinucleated, DAPI+GFP+ parasites were seen within CD317+ DCs (Fig. 2A, arrow), and parasites of similar appearance were also visible within Ter119+ pRBC (Fig. 2B, red). Studies by transmission electron microscopy also showed multinucleated parasites within DCs (Fig. 2 C–E). Fig. 2D is a magnified image of the inset box shown on Fig. 2C to highlight the parasite has as a parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM). Fig. 2E is another higher magnification example of a parasite with multinuclear profiles.

Fig. 2.

Microscopy of Plasmodium within DC. Cohorts of naive mice were infected with PbGFP and DC isolated after 7 d for assessment by confocal microscopy. Representative confocal z-stack examples show (A) GFP+ (green) parasites with three small DAPI+ (blue) nuclei (arrow on gray-scale DAPI image) adjacent to a large DC nucleus (N). (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (B) GFP+ parasites in Ter-119+ RBC (marker for RBC). (C–E) Transmission electron micrographs. (C) DC with multinucleated (pN) parasite within DC, adjacent to the DC nucleus (N). (Scale bar, 1 μm.) (D) Magnified image of parasite in C Inset, to show PVM and Parasitophorous vacuole (PVac). (E) Another magnified example of a parasite in DC with two pN and rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) highlighted. (F) Confocal z-stack of DCs with EdU+ parasites (green), immunolabeled for the autophagosomal marker LC3 (red) and DAPI (blue). The DC shown has its own DAPI stained nucleus (N) as well as multiple EdU+DAPI+ PbGFP nuclei (arrows). Of note, actively dividing, EdU+ parasites did not usually colocalize with LC3 (arrowhead). (Scale bars, 5 μm.) (G) Flow cytometry profile of CD317+ DCs with parasite-associated GFP and uptake of EdU by replicating parasites. (H) Percentage of total DCs with visible whole GFP+ trophozoites/schizonts with their own DAPI+ nuclei not associated with LAMP1.

To determine if the multinucleated GFP+ parasites seen within DCs were derived from replication within CD317+ DC, these DCs were isolated from spleens of PbGFP-infected mice and cultured for 15 to 18 h in the presence of 5 ethynyl-2′deoxyuridine (EdU) that is incorporated into replicating DNA. The cells were then processed to detect EdU, labeled for CD11c expression and DAPI, and then CD11c+EdU+DAPI+ DCs were cell-sorted for confocal microscopy. Multiple EdU+DAPI+ small parasite nuclei (arrows) were found inside these DCs (Fig. 2F), indicating that some parasites were proliferating within the DCs as they had incorporated EdU into their DNA during replication within cultured DCs. These EdU+DAPI+ small parasite nuclei did not, however, colocalize with the autophagosome marker LC3 in the same cell (Fig. 2F, arrowhead). Dividing EdU+DAPI+ parasites were never associated with lysosomal or autophagocytic membranes. Other studies found that ∼25% (range of 14–40%) of GFP+CD317+ DCs had replicating parasites at the time of culture, seen by incorporated EdU (Fig. 2G). This finding was supported by microscopic analysis of ex vivo CD317+ DCs containing GFP+ parasites, which found equivalent numbers of DCs had single or multiple green parasites, suggesting many of the infected DCs had probably supported proliferation in vivo (Fig. 2H).

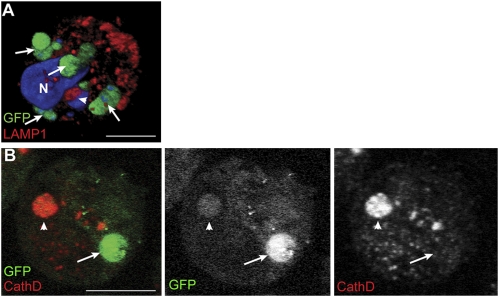

Additional labeling of CD317+ DCs was undertaken as DCs, by nature, degrade all proteins taken up by endocytosis/pinocytosis except those maintained for transfer to naive B cells (22). These studies found that when GFP+ parasites were adjacent to or colocalized with the late endosome/lysosome markers, LAMP1 (early lysosome associated membrane protein-1) (Fig. 3A, arrowhead) and cathepsin D (Fig. 3B, arrowhead), GFP labeling was reduced, suggestive of parasite degradation. However, there were also GFP+ parasites that did not colocalize with these markers (Fig. 3 A and B, arrows; and Movie S1, which is a 3D reconstruction of a PbGFP-infected CD317+ DCs).

Fig. 3.

P. berghei and lysosomal markers within CD317+ DCs. Cohorts of naive mice were infected with PbGFP and CD317+ DC isolated after 7 d for assessment by confocal microscopy. Representative confocal z-stack examples show (A) CD137+ DCs with whole (arrows) and degrading (arrowhead) PbGFP, immunostained with LAMP1 (red) and DAPI (blue), reconstructed to give a 3D view. Most Plasmodia are GFP+ but one, adjacent to a late endosome (red), has lost its GFP (arrowhead). (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (B) Cathepsin D-labeled sections show an inverse staining of a weak GFP+ schizont in cathepsin D+ lysosomes (arrowhead) and one with strong GFP that is not in a labeled lysosome (arrow). (Scale bar, 5 μm.)

CD317+ DCs Are Infected in Vitro by P. berghei Schizont-Infected RBC in Culture.

In vitro culture followed by adoptive-transfer studies were undertaken to determine if CD317+ DC could be infected in vitro and transfer infection. Total CD11c+ DC or CD317+ DC were isolated from naive mice and multiple samples cultured with PbGFP schizont-infected RBC. In parallel, similar numbers of schizont-infected RBC were cultured alone without DCs under similar conditions for 42 to 48 h.

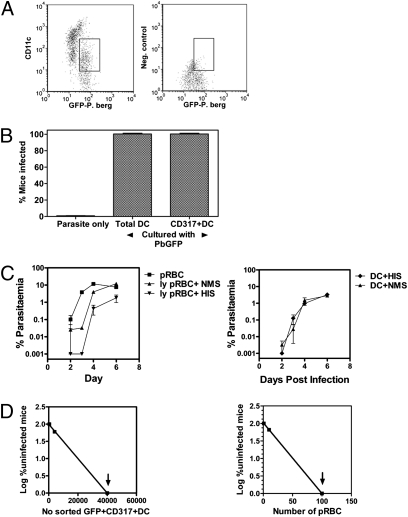

After 24 h, a sample of the CD11c+ DCs cultured with parasites was examined by flow cytometry and GFP was found to be predominantly associated with the CD11clo population of DCs (Fig. 4A). After 42 to 48 h, aliquots of all parasite cultures with or without DCs were injected intravenously into naive mice (106 DC per mouse), which were monitored for infection (Fig. 4B). All mice given CD11c+ DC or CD317+ DC cultured with schizont-infected RBC developed an infection. In contrast, after the 42 to 48 h in culture, no infection was detected in mice given schizont-infected RBC cultured alone. This series of studies showed that the culture conditions used did not support survival of PbGFP schizont-infected RBC, but that CD317+ DCs could support the survival of PbGFP schizont-infected RBC in vitro and infect naive mice on transfer of the DCs. Furthermore, despite extensive attempts, we have never seen red cell membranes surrounding parasites within DCs, suggesting that merozoites may be released by PbGFP schizont-infected RBC in culture and invade DCs.

Fig. 4.

CD317+ DCs harbor infectious Plasmodia. To infect DC in vitro, total CD11c+ DCs or CD317+ DCs were isolated from naive mice and cultured with PbGFP schizonts for 42 to 48 h. Schizonts were cultured alone in parallel. All cultures were then transferred to multiple cohorts of naive mice (n = 4–5 per group), which were then smeared every 2 to 3 d to detect infection. (A) CD11clo DC show uptake of PbGFP after 24-h culture compared with cells labeled with isotype control antibody. Parallel samples of cultures with schizonts only were used to define infected red cells based on GFP, size, and granularity. Gate highlights that DCs with low CD11c expression take up the parasite. (B) Total CD11c+ DCs or CD317+ DCs from naive mice support PbGFP schizont survival in vitro as seen by the transfer of infectious Plasmodium to naive mice. Data represent four independent experiments with similar results. (C) Extracellular merozoites are not the source infection in DC preparations. Ter119+GFP+ RBC (pRBC) or GFP+CD11c+Ter119− DCs were from blood or spleen of PbGFP-infected mice were treated with Gey's solution (to free merozoites) and an equal volume of either hyperimmune serum specific for P. berghei (HIS) or serum from naive mice (NMS) was added immediately. Cohorts of naive mice were transfused with either 104 intact pRBC per mouse, lysed-equivalent per mouse (ly pRBC; Left) or 104 DCs and all mice monitored daily for infection (Right). The data represent one of two experiments with groups of four mice, which had similar results. Error bars shown are Mean parasitemia ± SEM. (D) To calculate the frequency of CD317+ DC that support parasites in vivo, cohorts of mice were infected with PbGFP and GFP+CD317+ DC isolated after 8 d for transfer to naive recipients. Plots of the percentage of uninfected mice versus numbers of GFP+CD317+ DCs or pRBC from PbGFP-infected mice were used to calculate the frequency of infected DC or pRBC. (y = mx + c was used to calculate the frequency of infectious DCs). The arrows indicate that all mice were infected.

Demonstration That Infected RBC Were Not the Source of Infection in DC Preparations.

Although we could not detect contaminating pRBC by Ter119 labeling of our DC preparations, it could be argued that the infection was transferred as a result of a small number of contaminating infected RBC in the DC preparations. To analyze this further, we isolated CD317+ DCs from mice at day 7 after infection with PbGFP. These DCs were then labeled with CD11c and Ter119 for FACS sorting of Ter119−CD11c+CD317+GPF+ DCs or Ter119−CD11c+CD317+GPF− DCs, which were transferred to groups of naive mice. Although GFP+ DCs transferred the infection, no mouse given GFP− DCs developed infection (Table 1). This result demonstrated that our sorting method was highly sensitive in discriminating between infectious and noninfectious cells.

Table 1.

Frequency of CD317+ DC that transfer infectious Plasmodium to naive mice

| Cell transferred | Frequency of infectious cells |

| GFP+ RBCs | 1/22 Infectious |

| GFP+ CD317+ DC | 1/8,631 Infectious (360 DC/spleen) |

| GFP−CD317+ DC (104) | No transfer of infection |

| GPF+ CD317− DC (104) | No transfer of infection |

| GFP+ CD8+ DC (104) | No transfer of infection |

| P. yoelii pRBC | 1/22 Infectious |

| P. yoelii CD317+ DC | 1/2,193 Infectious (4,559 DC/spleen) |

Naive mice were infected with PbGFP or P. yoelii 17XNL and CD317+ DCs isolated after 7 d. Titrating numbers (106,105, 104, 103, 102, 101) of sorted GFP+CD317+ DCs, GFP−CD317+ DCs, GFP+CD317− DCs, GFP+CD8+ DCs, GFP+ red cells (pRBC) from PbGFP infections or P. yoelii 17XNL pRBC and CD317+ DCs from P. yoelii 17XNL infections were transferred to multiple cohorts of naive mice (n = 5–10 per group), which were then smeared every 2 to 5 d to detect infection for up to 30 d. A plot of the log-percent uninfected mice versus number of transferred cells (Fig. 4D and Fig. S2) was used to calculate the frequency CD317+ DCs required to transfer infection. Data are representative of two to three independent experiments with similar results.

To further demonstrate that contaminating pRBC were not responsible for transferring the infection, CD317+ DCs were isolated from naive mice and mixed with infected RBC in a DC:pRBC ratio of 1:20 or 1:80. One-half of the sample was immediately treated with Gey's solution to lyse RBC, CD317+ DCs reisolated by MACS (magnetic-activated cell sorting) columns and then labeled with antibody specific for CD11c. The CD11c+ DCs were cell-sorted and 106 DCs per mouse transferred to naive mice. The other half of the sample was not treated with Gey's solution and adjusted to transfer an equal number of DCs (106 per mouse) to naive mice. In duplicate experiments, untreated DC transferred the infection but all DC preparations treated with Gey's solution and isolated failed to transfer infection, confirming our standard DC isolation procedure removed infected RBC.

To demonstrate that cell surface-associated merozoites, released following Gey's lysis of pRBC, were not responsible for the transfer of infection by GFP+CD11c+ DCs, blocking studies were undertaken (Fig. 4C). For these studies, Ter119+GFP+ RBC and GFP+CD11c+Ter119− DCs were isolated from PbGFP-infected mice, treated with Gey's solution (to free merozoites), followed by incubation with an equal volume of either hyperimmune serum specific for PbGFP (HIS) or naive mouse serum (NMS) before transfusion into naive mice. The treatment of lysed pRBC with HIS delayed the detection of parasitemia in recipient mice by 1 d, with nearly 10-fold lower parasitemia, compared with freed merozoites treated with NMS (Fig. 4C; Left). In contrast, HIS did not affect the infectivity of DCs (Fig. 4C; Right). These studies showed that the parasites were internalized into DCs and were protected from antibodies capable of neutralizing free merozoites.

Plasmacytoid DCs from PbGFP, P. yoelii 17XNL, and Pladmodium chabaudi-infected Mice Are Infectious to Naive Mice.

To demonstrate whether CD317+ DCs also supported parasite survival in vivo, GFP+CD317+CD11c+Ter119− DCs were isolated from spleens of mice infected with PbGFP. In particular, RBC in the spleen cell preparation were lysed by Gey's solution and cell preparations were passed through a MACS magnet to deplete hemozoin, residual schizonts, or any other cell containing hemozoin, before positive selection of GFP+CD317+CD11c+Ter119− DCs. Titrating numbers of these DCs (10–106) or infected RBC (10–104) were transferred to groups of naive mice (n = 10) and monitored for the development of blood-stage infections. Using a limiting dilution analysis, it was estimated that ∼1 in 8,631 GFP+CD317+CD11c+Ter119− DCs taken from infected mice were infectious (Fig. 4D and Table 1), which equates to ∼360 to 580 infectious DCs per spleen, as the spleens of infected mice have 3 to 5 × 106 CD317+ DCs during a PbGFP infection (Fig S1D). Equivalent numbers (104) of GFP−CD317+CD11c+ DCs, GPF+CD317−CD11c+, or GFP+CD8+ DCs from infected mice did not transfer the infection (Table 1). In comparison, 1 in 22 PbGFP-infected RBC were infectious (Table 1). Similarly, when CD11c+CD317+ DCs isolated from mice infected with P. yoelii 17XNL and transferred to naive mice, 1 in 2,193 DCs was infectious (Table 1 and Fig. S2) which, based on numbers of DCs per spleen, equates to 4,559 infectious DC per spleen (Table 1).

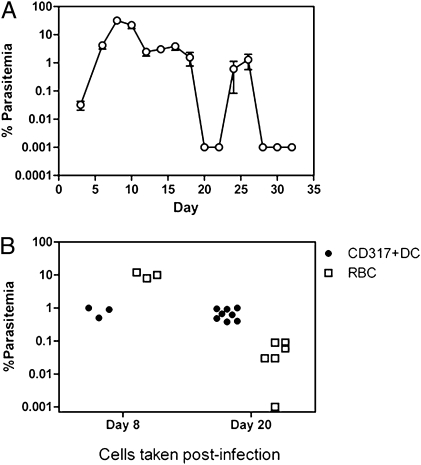

To determine if CD317+ DCs harbored Plasmodium after the apparent clearance of infection, cohorts of mice were infected with nonlethal P. chabaudi, which clears patent parasitemia within 20 d followed by recurrent bouts of low-level recrudescent parasitemia (Fig. 5A). Purified CD317+ DCs and infected RBC were taken after 8 d during peak parasitemia and after 20 d, when no parasitized RBC were observed by microscopy, and equal cell numbers (105 on day 8 and 106 on day 20) transferred to naive recipients. Recipient mice were smeared daily to detect the first appearance of parasites. All mice given RBC or CD317+ DCs taken from mice during peak parasitemia (day 8) developed infections, although the mice given RBC generated higher parasitemia on day 6 posttransfer compared with mice given DC (Fig. 5B). However, when RBC or CD317+ DCs were taken from mice after the apparent clearance of blood-stage infection (day 20), eight of eight mice given 106 CD317+ DCs developed ∼0.67% parasitemia by day 6, compared with five of six mice that received RBC and only developed ∼0.05% (P < 0.0007) parasitemia by the same day (Fig. 5B). These data show that during the subpatent stage of infection as measured by blood smears, CD317+ DC can harbor parasites and transfer infection more efficiently than the lower level of infection by RBC.

Fig. 5.

CD317+ DCs harbor P. chabaudi during subpatent parasitemia. To determine if CD317+ DC could harbor parasite during subpatent parasitemia, multiple cohorts of mice were infected with nonlethal P. chabaudi AS. (A) The percentage of parasitemia monitored for one round of infection (Mean ± SEM; n = 5). (B) DCs or RBC were taken after 8 d during peak parasitemia and after 20 d when no patent parasite was observed by blood-smear microscopy (<0.001%). On day 8, 105 CD317+ DCs or pRBC and on day 20, 106 CD317+ DCs or RBC were transferred to naive mice and blood smears made daily for first sign of infection. Data represents two independent experiments with similar results.

Discussion

This study shows that rodent-infecting blood-stage Plasmodium spp. have a tropism for splenic CD317+ DCs, which can promote their survival and replication and that ∼360 to 4,559 DCs per spleen will sustain infectious parasites. Furthermore, in studies of nonlethal infections with P. chabaudi, these parasitized DCs can release infectious parasites even during subpatent infections. Confocal microscopy studies established that multinucleated parasites were within DCs and not associated with the extracellular membrane folds, as described for the Toxoplasma tachyzoites (23) or associated with extracellular infected RBC. Additional experiments also excluded extraneous RBC or merozoites as being the source of the infection in transfer studies. Furthermore, the observation that only GFP+CD317+CD11c+Ter119− DCs but not GFP+CD317−CD11c+Ter119− DCs or GFP+CD8+ DCs could transfer infections to naive mice, highlighted that only CD317+ DC supported Plasmodium and transferred infectious parasites.

CD317 is a marker of Plasmacytoid DC (PDC) in naive mice but unique DC populations, termed “inflammatory DCs,” which are not found in the steady state can appear as a consequence of infection or inflammation (24) and may express this molecule following IFN stimulation (21). Our data show that the GFP+ DCs are heterogeneous in surface expression, but consistent with the infected CD317+ DC being predominantly PDCs because GFP+ DCs secreted more IFN-α than GFP− DCs in infected mice (Fig. S3); >50% consistently expressed B220 and Ly6G which are markers of PDC, and <30% were DEC205+ (25). Furthermore, PDC are long-lived (14-d limit of testing) compared with conventional DCs (<3 d) (25), and thus we hypothesize would be better able to harbor infectious parasites even after peak parasitemia has cleared. Finally, we were able to show CD317+ DC from naive mice could take up PbGFP from schizont-infected RBC, possibly through invasion as opposed to phagocytosis. These parasites within DCs survived for up to 48 h in vitro and transferred infection to naive mice. Unfortunately, because of the very low numbers of infectious DCs in the spleen and following in vitro infection, we were unable to reliable quantify cell cycle characteristics and determine if the parasites had: (i) a very prolonged cell cycle with a slow development of trophozoites/schizonts; (ii) “arrested forms” that can survive for prolonged periods after which a small percentage develop into infective merozoites; or (iii) a normal cell cycle of 22 to 24 h comparable to asexual blood stages in host RBC which constantly reinfect DC. Based on the low infectivity of DCs on transfer to naive mice and the observation that CD317+ DC can harbor parasites and transfer infection at similar levels during peak and subpatent infections, we hypothesize that these DCs may hold arrested forms of parasites that survive for extended periods. If DCs were constantly reinfected, then like RBC, their infectivity would have been higher during peak parasitemia. Finally, we also suggest that arrested forms would have a survival advantage over just having a prolonged cycle.

Based on our data, we hypothesize that the survival of Plasmodium within immuno-privileged DCs may facilitate evasion from immune surveillance. The observation of blood-stage parasites surviving and replicating only within spleen DCs is consistent with observations of malaria in primates, where it has been shown that primate malaria P. inui persists for the life of the host and infection is only cleared if the spleen is removed after infection (12). Although some monkeys died from high parasitemia after splenectomy, those that survived were able to clear the infection within 6 mo (12). One explanation for the effect of splenectomy on radical cure of the infection is the possible survival of parasites within DCs in the spleen. This observation also has implications for human malaria. It is known that in patients with a previous history of malaria, often with no new infections for many years, following splenectomy suffer an abrupt onset of Pladmodium falciparum (26), P. malariae (27), and Plasmodium vivax (28) malarias. These splenectomies usually follow splenic trauma. We thus hypothesize that trauma to the spleen may disturb CD317+ DCs to release parasites and trigger these relapses with malaria.

In conclusion, we have found that CD317+ DCs can support the survival of the blood-stage of rodent malaria parasites, P. berghei, P. chabaudi, and P. yoelii 17XNL. Whether DCs are a reservoir for human Plasmodium spp. remains to be determined. Such findings could have important implications for the development of vaccine strategies and potentially new antimalarial therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Please refer to the SI Materials and Methods for details, materials, and experimental rationale.

Animals.

Specific pathogen-free, 6- to 8-wk-old female C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the Animal Resources Centre. All animal procedures were approved and monitored by the Queensland Institute of Medical Research Animal Ethics Committee. This work was conducted under Queensland Institute of Medical Research animal ethics approval number A0209-623M, in strict accordance with the “Australian code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes” (Australian National Health and Medical Research Council).

Preparation of Spleen Cells Depleted of RBC.

Cohorts of 3 to 20 mice were infected intravenously with 104 PbGFP or 105 P. yoelii 17XNL, or P.chabaudi AS-infected RBC. The PbGFP line, as described by Franke-Fayard et al., was shown to express GFP at all previously known blood stages and successfully used to identify infected RBC by FACS (18). Spleens from naive or infected C57BL/6J mice were digested with Collagenase D (Roche Diagnostics) and DNase (Boehringer), as previously described (22). Approximately 1 × 108 pelleted spleen cells were resuspended in 1 to 2 mL of Gey's solution and incubated on ice for 1 to 3 min, shaking occasionally. The lysis was stopped with Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Media (IMDM; Invitrogen) containing 5% FCS. The digested spleen cell suspension was then incubated with 100 μg/mL Rat IgG, to block FcR binding of subsequently used labeling antibodies.

Isolation of Spleen DCs.

Total DC populations were enriched from digested spleen cells with Dynabeads Mouse DC enrichment kit (Dynal) and additional Dynal anti-IgM beads. These cell preparations were then passed through MACS columns on a magnet without any prior labeling to deplete hemozoin, residual schizonts, or any other cells containing hemozoin. The DC-enriched cells were then labeled with anti-CD11c or anti-PDCA (CD317) MACS microbeads to isolate total CD11c+ DC or CD317+ DC, respectively (Miltenyi Biotec Gmb).

To isolate GFP+CD317+ DCs, the CD317+ DCs were labeled with anti–CD11c-APC and Ter119-PE, and using a narrow gate on the pulse-width settings (to exclude doublets), large GFP+CD317+CD11c+Ter119− DCs were sorted on a MoFlo (Beckman Coulter) or FACSAria III cell sorter (BD Bioscience).

PbGFP Cell Transfer Studies.

Titrating numbers of sorted GFP+Ter119 RBC (10–104) or GFP+CD317+CD11c+Ter119− DCs (10–106) per mouse were injected intravenously into cohorts of 5 or 10 naive mice per group. The development of blood-stage infections in these mice was monitored by analysis of Giemsa stained blood films made from tail blood every 1 to 2 d until infection was patent in control groups or up to 3 wk.

P. yoelii 17XNL and P. chabaudi Cell Transfer Studies.

To isolate CD317+CD11c+Ter119− DCs, CD317+ DCs were isolated from spleens of infected mice using the method described in the previous sections and CD317+CD11c+Ter119− DC were then cell-sorted.

Confocal Microscopy.

GFP+CD11c+CD317+ DCs (day 7) from PbGFP-infected mice were immobilized on poly-l-lysine–coated slides (Sigma) and labeled to detect LAMP1 (BD Bioscience), LC3 (ubiquitin-like protein Atg8, which is a marker of autophagy; clone 5F10; Alexis Biochemicals), Cathepsin D, and nuclear DNA with DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Invitrogen), as indicated in the text using immuno-fluorescent–labeling techniques described previously (29). Microscopy was performed on a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Electron Microscopy.

DCs were isolated as for light microscopy and then processed for standard EM by fixation in glutarahdehyde, postfixation in potassium ferricyanide-reduced osmium tetroxide and uranyl acetate, and embedding in Epon resin following standard protocols.

Preparation of Schizonts.

Mature schizonts were isolated from in vitro culture of synchronized ring forms as described by Janse et al. (19) using Nyodenz density-gradient centrifugation (Nycodenz 1.077A; NycoMed) or Optiprep (Axis Shield).

In Vitro Infections of DCs.

Total CD11c+ DCs or CD317+ DCs were isolated from naive mice (PDC) using MACS and cultured (1–2 × 106 per tube) with isolated schizonts in IMDM with 10% FCS in poly styrene tubes, at an approximate ratio of one-to-two schizonts per DC. As controls, equivalent numbers of schizonts were cultured in parallel. After 40 to 48 h, PBS was added to all cultures, cell spun down at 200 × g, resuspended in PBS, transferred to naive mice (5 × 105 PDC per mouse) by intravenous injection, and all mice monitored daily for infection.

Experiment to Exclude Red Cell Contamination.

For these studies, ∼2 × 106 CD317+ DCs were isolated from naive mice and mixed with 1.6 × 108 infected RBC (80-fold; 1.15 × 109 total RBC). The sample was divided into two halves and one stored on ice. The other half was treated with Gey's solution, DCs reisolated by MACS, and cell-sorted for CD11c cells. Five naive mice per group were each transfused with 1 × 105 sorted CD11c+CD317+ DCs or unsorted 1 × 105 CD11c+CD317+ DCs with 8 × 106 infected red cells from the untreated preparations. In the duplicate experiment, 4 × 106 DCs was mixed with 8 × 107 infected red cells (20-fold) and treated as described above.

Experiment to Exclude Extracellular Merozoites as a Source Infection in DC Preparations.

Ter119+GFP+ RBC and GFP+CD11c+Ter119− DCs were isolated by cell sorting from the blood and spleens of PbGFP-infected mice, respectively. All cell preparations were treated with Gey's solution (to free merozoites) for 1 to 2 min. One-half of the preparation was then incubated with hyperimmune serum specific for P. berghei (diluted 1/2 in culture media), produced by repeated infection of mice followed by drug cure with pyrimethamine. The other half was incubated with mouse serum from naive mice (diluted 1/2 in culture media). After 30 min, cohorts of four naive mice were transfused with 104 intact pRBC per mouse, lysed-equivalent per mouse or 104 DC, and all mice monitored daily for infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Denise Doolan, Christian Engwerda, and James McCarthy for their critical reading of the manuscript; Drs. Alan Sher and Leanne Tilley for their discussion of the data; Ms. Grace Chojnowski and Paula Hall for their excellent cell sorting skills; and Ms. Virginia McPhun for her technical assistance with some of the earlier developmental assays. This study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1108579108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Medica DL, Sinnis P. Quantitative dynamics of Plasmodium yoelii sporozoite transmission by infected anopheline mosquitoes. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4363–4369. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4363-4369.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gueirard P, et al. Development of the malaria parasite in the skin of the mammalian host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18640–18645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009346107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amino R, Thiberge S, Shorte S, Frischknecht F, Ménard R. Quantitative imaging of Plasmodium sporozoites in the mammalian host. C R Biol. 2006;329:858–862. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanderberg JP, Chew S, Stewart MJ. Plasmodium sporozoite interactions with macrophages in vitro: A videomicroscopic analysis. J Protozool. 1990;37:528–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1990.tb01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pradel G, Frevert U. Malaria sporozoites actively enter and pass through rat Kupffer cells prior to hepatocyte invasion. Hepatology. 2001;33:1154–1165. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishino T, Yano K, Chinzei Y, Yuda M. Cell-passage activity is required for the malarial parasite to cross the liver sinusoidal cell layer. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(1):E4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mota MM, et al. Migration of Plasmodium sporozoites through cells before infection. Science. 2001;291(5509):141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5501.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sturm A, et al. Manipulation of host hepatocytes by the malaria parasite for delivery into liver sinusoids. Science. 2006;313:1287–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1129720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prudêncio M, Rodriguez A, Mota MM. The silent path to thousands of merozoites: The Plasmodium liver stage. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:849–856. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiburskaja NA, Vrublevskaja OS. Clinical and experimental studies on quartan malaria following blood transfusion and methods for preventing its occurrence. Bull World Health Organ. 1965;33:843–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt LH, Fradkin R, Harrison J, Rossan RN, Squires W. The course of untreated Plasmodium inui infections in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29(2):158–169. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyler DJ, Miller LH, Schmidt LH. Spleen function in quartan malaria (due to Plasmodium inui): Evidence for both protective and suppressive roles in host defense. J Infect Dis. 1977;135(1):86–93. doi: 10.1093/infdis/135.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landau I, et al. Survival of rodent malaria merozoites in the lymphatic network: Potential role in chronicity of the infection. Parasite. 1999;6:311–322. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1999064311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fajardo LF. Letter: Malarial parasites in mammalian platelets. Nature. 1973;243:298–299. doi: 10.1038/243298a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkash A, Kelly NI, Fajardo LF. Enhanced parasitization of platelets by Plasmodium berghei yoelii. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78:451–455. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(84)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huff CG. Organ and tissue distribution of the exoerythrocytic stages of various avian malarial parasites. Exp Parasitol. 1957;6(2):143–162. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(57)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirunpetcharat C, et al. Absolute requirement for an active immune response involving B cells and Th cells in immunity to Plasmodium yoelii passively acquired with antibodies to the 19-kDa carboxyl-terminal fragment of merozoite surface protein-1. J Immunol. 1999;162:7309–7314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franke-Fayard B, et al. A Plasmodium berghei reference line that constitutively expresses GFP at a high level throughout the complete life cycle. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;137(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janse CJ, Ramesar J, Waters AP. High-efficiency transfection and drug selection of genetically transformed blood stages of the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:346–356. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inaba K, et al. High levels of a major histocompatibility complex II-self peptide complex on dendritic cells from the T cell areas of lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 1997;186:665–672. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blasius AL, et al. Bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 is a specific marker of type I IFN-producing cells in the naive mouse, but a promiscuous cell surface antigen following IFN stimulation. J Immunol. 2006;177:3260–3265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wykes M, Pombo A, Jenkins C, MacPherson GG. Dendritic cells interact directly with naive B lymphocytes to transfer antigen and initiate class switching in a primary T-dependent response. J Immunol. 1998a;161:1313–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Courret N, et al. CD11c- and CD11b-expressing mouse leukocytes transport single Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites to the brain. Blood. 2006;107:309–316. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shortman K, Naik SH. Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(1):19–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Keeffe M, et al. Mouse plasmacytoid cells: Long-lived cells, heterogeneous in surface phenotype and function, that differentiate into CD8(+) dendritic cells only after microbial stimulus. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1307–1319. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Looareesuwan S, Suntharasamai P, Webster HK, Ho M. Malaria in splenectomized patients: report of four cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:361–366. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuchida H, Yamaguchi K, Yamamoto S, Ebisawa I. Quartan malaria following splenectomy 36 years after infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31(1):163–165. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garnham PC. The role of the spleen in protozoal infections with special reference to splenectomy. Acta Trop. 1970;27(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manderson AP, Kay JG, Hammond LA, Brown DL, Stow JL. Subcompartments of the macrophage recycling endosome direct the differential secretion of IL-6 and TNFalpha. J Cell Biol. 2007;178(1):57–69. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.