Abstract

It is well-appreciated that viruses use host effectors for macromolecular synthesis and as regulators of viral gene expression. Viruses can encode their own regulators, but often use host-encoded factors to optimize replication. Here, we show that Drosha, an endoribonuclease best known for its role in the biogenesis of microRNAs (miRNAs), can also function to directly regulate viral gene expression. Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated Herpesvirus (KSHV) is associated with various tumors, and like all herpesviruses, has two modes of infection, latent and lytic, which are characterized by differential expression of viral gene products. Kaposin B (KapB) is a KSHV-encoded protein associated with cytokine production and cytotoxicity. We demonstrate that in addition to previously known transcriptional mechanisms, differences in Drosha levels contribute to low levels of KapB expression in latency and robust increases in expression during lytic replication. Thus, surprisingly, KSHV modulates Drosha activity differentially depending on the mode of replication. This regulation is dependent on Drosha-mediated cleavage, and KapB transcripts lacking the Drosha cleavage sites express higher levels of KapB, resulting in increased cell death. This work increases the known functions of Drosha and implies that tying viral gene expression to Drosha activity is advantageous for viruses.

Keywords: microprocessor, cis-regulation 3' UTR

Understanding how viruses regulate their own gene expression is an active area of research with relevance to numerous diseases. Viruses with RNA genomes typically rely on RNA binding proteins and cis transcript elements to control gene expression (1). For DNA viral gene regulation, host and viral transcription and chromatin-associated factors are best characterized (2, 3), with the role of cis RNA regulatory elements understudied. Recently, some DNA viruses have been shown to encode trans regulatory small RNAs, called microRNAs (miRNAs), that bind to mRNAs and negatively regulate host or viral gene expression. Over 200 miRNAs have been described from viruses with DNA genomes that undergo a nuclear replication cycle (reviewed in refs. 4 to 6). Like host-encoded miRNAs, the functions of the majority of viral miRNAs are unknown. Few viral miRNAs are homologous with host miRNAs, and this implies that most viral miRNAs will either regulate viral transcripts or host transcripts via unique binding sites (7), or possibly that viral miRNAs may have novel, as yet unknown functions.

Viruses use the host machinery for miRNA biogenesis, including the nuclear microprocessor complex containing the double-stranded RNA endonuclease Drosha and its binding partner DGCR8. Drosha cleaves the primary miRNA transcript to liberate a hairpin secondary structure called a pre-miRNA (reviewed in ref. 8). The pre-miRNA is then exported to the cytoplasm and further processed into the functioning miRNA (Fig. 1A). Drosha cleavage also mediates direct cis-regulation of DGCR8 mRNA levels and, thus, serves as a mechanism to autoregulate its own miRNA biogenesis activity (9). In addition, it is likely that some additional mRNAs (containing pre-miRNA-like structures) are also directly regulated by Drosha-mediated cleavage, but these transcripts have not been well-characterized and no functional significance has been attributed to this possible mode of regulation (10, 11). It is unknown whether viral transcripts are regulated via a similar mechanism, but at least five different viruses [Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), murine cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr Virus (EBV), and Marek's disease viruses 1 and 2] encode transcripts containing pre-miRNA structures located within an mRNA (4). This finding suggests Drosha-mediated cis-regulation of gene expression may be a common regulatory strategy among divergent herpesviruses.

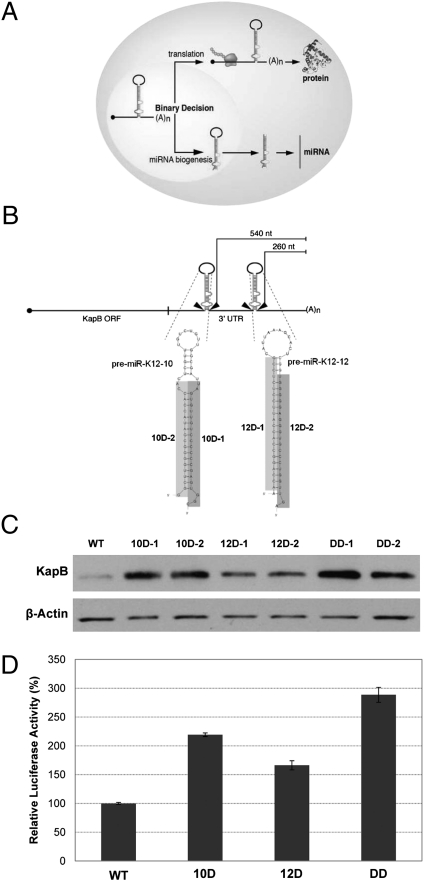

Fig. 1.

Some KSHV pre-miRNAs mediate cis-regulation of KapB transcripts. (A) Diagram of binary decision hypothesis. (B) Diagram of the KapB transcript. The 3′ UTR of KapB contains premiRs K12-10 and K12-12. The distance (in nucleotides) from the polyadenylation cleavage site for each pre-miRNA is indicated for constructs expressing KapB. The shaded regions denote the deleted sequences of each pre-miRNA possessed by the D-1 and D-2 series mutants. Note, the DD-1 mutant refers to a double mutant of the D-1 sequences in both premiRs K12-10 and K12-12, and DD-2 refers to a double mutant of both D-2 sequences in premiRs K12-10 and K12-12. Unless otherwise noted, the “DD” nomenclature refers to the DD-1 double mutant. (C) Immunoblot analysis demonstrates that KapB expression increases when the pre-miRNA structures are mutated. HEK293T cells were transfected with various constructs and immunoblot analysis performed with indicated antibody. β-Actin is shown as a load control. (D) Luciferase assay confirms regulatory roles of pre-miRNA structures. Wild-type or mutant KapB 3′ UTR sequences were cloned downstream of the firefly luciferase ORF, and these vectors were transfected into HEK293T cells along with a Renilla luciferase expression vector. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were harvested and assayed for luciferase activity. The data are shown as firefly normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

KSHV is a lymphotropic virus associated with hyperproliferative B-cell disorders and Kaposi's Sarcoma (KS), a highly vascularized lesion, composed mainly of endothelial cells, which afflicts mostly immunocompromised patients (12). Like all herpesviruses, KSHV has both a “latent” phase of infection, whereby only a few viral transcripts are expressed, and a “lytic” phase, whereby the remaining (of the n = ∼85) viral mRNA transcripts are expressed, culminating in lysis of the infected cell and the release of progeny virions (13). Although most KSHV gene products are classified strictly as either latent or lytic proteins, Kaposin B (KapB) is atypical in that it is constantly transcribed at a low level during latency, but is also dramatically induced upon lytic replication (14). Although a complete understanding of this induction is lacking, part of this results from KapB being driven by two different promoters: one constitutively active in latency and one that is activated during lytic replication by a viral “master lytic switch” transcription factor, RTA (Fig. S1) (14–16). Exogenous expression of KapB has been shown to have cytotoxic effects and also to induce the p38 stress-kinase signaling pathway (14, 17). Thus, proper regulation of the kinetics and abundance of KapB expression are likely important to the fitness of the virus.

Compared with other KSHV transcripts, KapB is unique in that within its 3′ UTR are two pre-miRNAs that give rise to miRs K12-10 and K12-12 (18). In this work, we set out to test whether these pre-miRNAs could play a negative cis-regulatory role on KapB transcripts. We demonstrate that Drosha-mediated cleavage of these pre-miRNAs negatively regulates KapB protein levels in latently infected cells. Furthermore, we show that this mode of regulation is inhibited during lytic replication. Thus, in addition to transcriptional regulation, decreased Drosha activity contributes to the differential levels of KapB that are made during the lytic and latent phases of infection. Therefore, this work expands the known functions of Drosha, and implies that viruses can use the miRNA biogenesis machinery for novel purposes in optimizing gene expression in lytic versus latent replication.

Results

Pre-miRNAs Encoding miRs K12-10 and K12-12 Are Negative cis-Regulatory Elements.

For transcripts that serve the dual role as both mRNA and primary miRNA, cleavage by Drosha is an irreversible action that should prevent nuclear export and subsequent translation of the cleaved mRNA. Thus, such transcripts face a binary decision of whether to become mRNAs or miRNAs (Fig. 1A). We therefore hypothesized that the pre-miRNAs encoding miRs K12-10 and K12-12, within the KapB 3′ UTR, function as negative cis-regulatory elements. Heterologous expression constructs were engineered in which premiRs K12-10, K12-12, or both were mutated to disrupt the characteristic secondary structure of a pre-miRNA. To minimize the chances of artifactual results if one of the mutants caused unintended, pre-miRNA-independent stabilizing effects, two different small internal deletion mutants were engineered for each pre-miRNA hairpin (Fig. 1B). Each mutant strategy (deleting either the sequence corresponding to miRNA strand or the passenger star strand) was used individually or in combination. These constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells and immunoblot analysis was conducted on total protein lysates. All mutant constructs resulted in increased expression of KapB protein, with premiR K12-10 playing a more readily detectable regulatory role than premiR K12–12 (Fig. 1C). Deleting both pre-miRNAs (DD-1 or DD-2) resulted in the greatest increase in KapB levels, suggesting both pre-miRNAs contribute to negatively regulate KapB transcripts. To ensure that the derivative miRNAs from premiRs K12-10 and K12-12 could not regulate coding portions of the KapB transcript in trans, reporter constructs were generated in which the KapB coding region was replaced with Luciferase. Luciferase assays were conducted on protein lysates harvested from cells transfected with these reporters. These results were significant, showing identical trends to what we observed for KapB protein (Fig. 1D). To further rule out the possibility of trans regulation by these miRNAs, cotransfection of plasmids expressing miRs K12-10 and K12-12 had no effect on KapB protein levels (Fig. S2). Combined, these results demonstrate that both premiRs K12-10 and K12-12 are negative cis-regulatory elements for KapB transcripts, with premiR K12-10 playing a greater role than premiR K12-12.

Drosha Mediates cis-Regulation of KapB Transcripts.

Having demonstrated that the pre-miRNAs in the KapB 3′ UTR are negative regulatory elements, we next tested whether Drosha cleavage plays a role in this regulation. Cotransfection of plasmids expressing Drosha and DGCR8 along with the various KapB 3′ UTR mutants resulted in decreased expression of KapB protein from all constructs tested except KapB-DD that has deletions of both the K12-10 and K12-12 pre-miRNAs (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the premiR K12-10 deletion was less susceptible to Drosha-mediated cleavage than the premiR K12-12 mutant, consistent with premiR K12-10 being the preferred substrate for Drosha (Fig. 2A, Right). Next, to directly assay for Drosha-mediated cleavage, RNA was harvested from these experimental treatments and Northern blot analysis was conducted using probes designed to recognize full-length and 3′ cleavage fragments of KapB mRNA. This analysis showed a band migrating at the expected position for full-length KapB mRNA, as well as bands migrating at the expected positions for the two 3′ fragments generated by Drosha-mediated cleavage of either premiRs K12-10 or K12-12 (Figs. 1B and 2B). Importantly, overexpression of Drosha/DGCR8 resulted in enhanced generation of the expected cleavage fragment for each construct, except KapB-DD, the double mutant lacking pre-miRNAs. [Note the mRNA/fragment ratio decreases for all constructs except KapB-DD in the presence of exogenous Drosha/DGCR8 (Fig. 2B)].

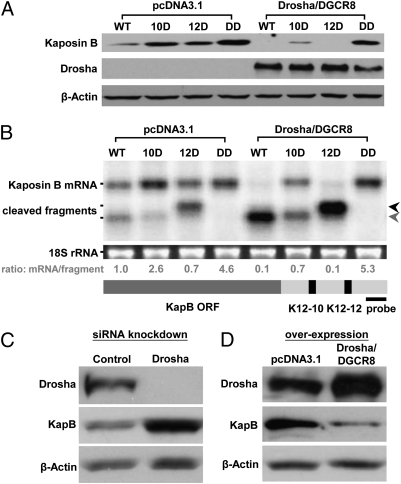

Fig. 2.

Drosha regulates KapB expression through processing of pre-miRNA cis elements. (A) Immunoblot analysis demonstrates that overexpression of Drosha and DGCR8 leads to decreased KapB expression. Various KapB expression vectors were cotransfected into HEK293T cells along with Drosha and DGCR8 expression vectors (see the legend for Fig. 1 B for description of KapB mutant vectors). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested for immunoblot analysis. Note, at this exposure level, only overexpressed and not endogenous Drosha levels are detectable. β-Actin levels are shown as a loading control. (B) Northern blot analysis demonstrates that overexpression of Drosha and DGCR8 leads to accumulation of cleaved fragments from KapB mRNA for those constructs that retain one or more pre-miRNAs in the 3′ UTR. Transfections were conducted as described in A. A ∼220-nt radiolabeled probe complementary to the 3′ end of the KapB transcript (diagrammed at bottom of B) was used to detect full-length KapB mRNA or the cleaved products. The calculated ratio of full-length KapB mRNA to cleavage fragments is shown below each lane. Note that the fastest migrating cleavage fragment band (indicated with gray arrow) could represent the cleavage product of either premiR K12-12 alone, or cleavage of both premiR K12-12 and premiR K12-10. The black arrow indicates the fragment generated by cleavage of premiR K12-10. (C and D) Drosha levels regulate KapB expression in KSHV-infected cells. (C) Decreasing Drosha levels increases KapB expression. Drosha siRNAs were transfected into TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells and immunoblot analysis was performed. (D) Increasing Drosha/DGCR8 levels decreases KapB expression. Drosha and DGCR8 expression vectors were cotransfected into TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells and immunoblot analysis was performed.

We next examined whether Drosha activity can regulate KapB expression in infected cells. BCBLs are primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cells that are predominantly latently infected with KSHV (19). A previously characterized Drosha-specific siRNA (9) was used to knockdown Drosha levels in TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells. Knockdown of Drosha protein was observed along with a concurrent increase in KapB protein levels (Fig. 2C). A reciprocal experiment, in which Drosha and DGCR8 proteins were overexpressed, resulted in the opposite phenotype (Fig. 2D). Importantly, control experiments show that knocking down Drosha levels does not ectopically induce RTA or surface K8.1 expression (hallmarks of lytic replication), thereby ruling out indirect RTA-mediated induction of KapB (Fig. S3). Thus, we conclude that Drosha-mediated cleavage directly regulates KapB transcripts and that this regulation occurs during bona fide infection at physiological levels of Drosha.

Physiological Consequences of Direct Drosha-Mediated Regulation of KapB Transcripts.

Having shown that Drosha can directly regulate the levels of KapB, we next addressed whether Drosha-mediated cis-regulation can affect the functionality of KapB. The original report describing KapB noted that it was difficult to generate cell lines stably expressing KapB, likely because of cytotoxicity associated with high levels of expression of this protein (14). We therefore developed a quantitative short-term cytotoxicity assay. Transfection of increasing amounts of plasmid encoding KapB into TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells resulted in an increasing proportion of dying cells, as evidenced by cells positive for propidium iodide and Annexin V staining (Fig. 3A). Next, we transfected cells with constructs expressing KapB with either the full-length 3′UTR (KapB-FL) or a double-deletion mutant 3′ UTR that is not cleaved by Drosha (KapB-DD). Transfection of control vector induced a baseline toxicity in the cells, and as expected, transfection of KapB-FL increased cytotoxicity (Fig. 3 B and C). Importantly, transfection of KapB-DD induced the highest level of dying cells, consistent with the increased levels of KapB produced from this construct. Notably, the degree of difference in KapB steady-state protein levels observed between the KapB-FL and KapB-DD constructs in these transient transfection assays is comparable to the differences in endogenous KapB levels observed in our Drosha knockdown studies (Fig. 2C), suggesting that Drosha-mediated regulation of KapB during latent infection is important for maintaining cell viability during latent infection.

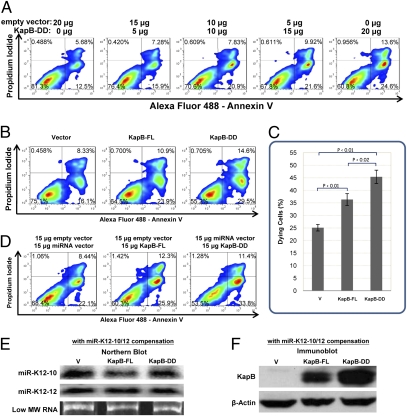

Fig. 3.

Direct Drosha-mediated regulation of KapB transcripts can affect biological activity of KapB protein. (A) KapB triggers cell death in a dose-dependent manner. Increasing amounts of the construct expressing the double-mutant KapB-DD (lacking both premiRs K12-10 and K12-12) were transfected to TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells. The total amount of DNA transfected was held constant by including differing amounts of the empty vector (pCR3.1). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested, and stained with Alexa Fluor 488 labeled Annexin V and propidium iodide. The samples were then analyzed by a FACS. Dying cells score within the lower right and upper left and right quadrants. (B and C) Transfection of the KapB construct lacking pre-miRNA cis elements results in increased cytotoxicity. TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells were transfected as described in A, or with a vector expressing KapB and with an intact full-length 3′ UTR (KapB-FL), or with a control empty vector (Vector). (C) Plotting the data of three independent replicates from the experiments shown in B. (D–F) The differences in cytotoxicity observed are not caused by the derivative miRNAs miRs K12-10 or K12-12. Empty vector, KapB-FL vector, or the KapB-DD vector were transfected into TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells along with vectors expressing miRs K12-10 and miR K12-12 to screen for any trans effects of derivative miRNAs in this cytotoxicity assay. (E) Northern blot analysis demonstrates that miRs K12-10 and K12-12 are expressed to comparable levels, whether derived from KapB-FL or from a separate miRNA-expression construct coexpressed with KapB-DD. RNA was harvested from TREx–RTA BCBL-1 cells transfected as described in D. (F) Immunoblot analysis from samples in D and E demonstrates differences in KapB protein expression levels between cells transfected with KapB-FL or KapB-DD persists even in the presence of trans-expressed miRs K12-10 and K12-12. For both D and E, “V” labels the control lane that was cotransfected with parental vector instead of a KapB expression vector.

To ensure that the increased cytotoxicity we observed in the absence of the KapB 3′ UTR pre-miRNAs was not because of trans targeting via the derivative miRNAs, identical experiments shown in Fig. 3 B and C were conducted, except that a vector expressing miRs K12-10 and K12-12 was also included. Cotransfection of the vector expressing miRs K12-10 and K12-12 along with the Kap-DD construct resulted in levels of miRNA expression approximately equal to those expressed from the KapB-FL vector (Fig. 3E). However, this result did not alter the increased KapB protein levels nor the increased cytotoxicity phenotype associated with the KapB-DD construct (Fig. 3 D and F). Combined, these data demonstrate that the differences in KapB protein levels associated with Drosha-mediated regulation are sufficient to alter the biological activity of KapB.

Drosha-Mediated Regulation Is Inhibited During Lytic Infection.

During the course of this study, we noticed what seemed to be relatively more induction of the KapB protein than the miRNAs miRs K12-10 K12-12 during lytic replication. This led us to hypothesize that Drosha has decreased steady-state levels and/or decreased activity during lytic replication. To test this hypothesis, we first conducted immunoblot analysis comparing Drosha protein levels during latency to several times postlytic induction. This analysis showed a decrease in Drosha steady-state levels beginning as early as 12 h postinduction, with the effect being dramatically enhanced during the course of RTA-responsive lytic infection (Fig. 4A). Concurrently, an increasing amount of KapB protein is observed, which was expected because of the increased transcription of the lytic promoter.

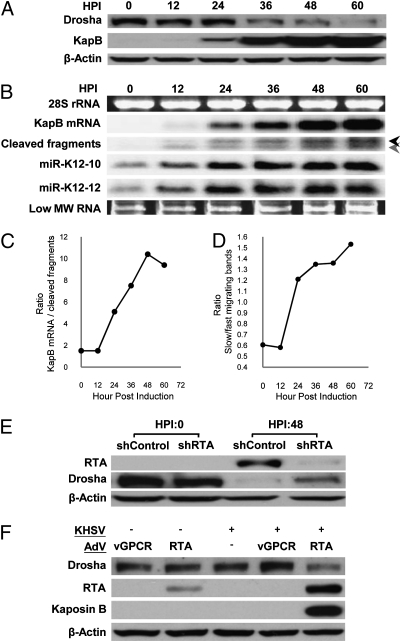

Fig. 4.

Lytic infection induces decreases in Drosha levels resulting in decreased cis-regulation of KapB transcripts. (A) KSHV lytic infection leads to down-regulation of Drosha protein levels in TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells. HPI, hours post induction of lytic replication. (B and C) Northern blot analysis demonstrates differences in the kinetics of accumulation of Drosha substrates and products in TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells at various times postinduction of lytic replication. (B) Full-length KapB mRNA shows robust increases starting at 24 HPI, whereas Drosha substrates (cleaved fragments and miRs K12-10 and K12-12) start accumulating as early as 12 HPI, but the degree of increase slows as Drosha levels diminish. The black arrow indicates the fragment generated by cleavage of premiR K12-10. The gray arrow indicates the products of transcripts cleaved at either premiR K12-12 alone, or at both premiR K12-12 and premiR K12-10 (see Fig. S1 for a detailed diagram). (C) The ratio of full-length KapB mRNA:KapB mRNA cleavage fragments changes during the course of lytic infection, demonstrating Drosha-mediated cleavage plays a greater regulatory role of KapB expression levels during latent infection. Shown is a representative plot of multiple independent experiments (similar to B) showing the ratio of full-length KapB mRNA:KapB mRNA cleavage fragments. (D) The ratio of fast:slow migrating cleavage fragments inverts during the course of lytic infection demonstrating decreased Drosha activity and that premiR K12-10 is a preferred Drosha substrate over premiR K12-12. Shown is a representative plot of multiple independent experiments (similar to B). (E and F) Independent models of KSHV lytic replication decrease Drosha levels. (E) To ensure lytic replication (and not the drug regimen used to induce PEL B cells into lytic replication) is responsible for the decreases in Drosha levels, lytic-inducing drugs were added to TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells transfected with an shRNA that knocks down RTA (the lytic switch protein whose expression is necessary and sufficient for lytic induction). Immunoblot analysis shows that partial knockdown of RTA results in increased Drosha levels. β-Actin levels are shown as a loading control. (F) KSHV de novo lytic infection of primary endothelial cells (HUVECs) results in decreased Drosha levels. “+” Indicates KSHV virus was added. Superinfection with an RTA-expressing adenoviral vector was used to induce lytic replication. An adenoviral vector expressing the viral protein vGPCR (which is not sufficient to induce lytic replication) was included as a negative control. Only coinfection with KSHV and the Ad-RTA vector negatively regulates Drosha levels. We note that double infection with Ad-RTA and KSHV results in increased levels of RTA over Ad-RTA infection alone. This finding is consistent with the previously characterized RTA autoregulation of its own promoter (31).

These results also suggest that increased KapB is partly attributable to decreased Drosha-mediated cleavage. To test whether the lytic-induced decrease in Drosha levels results in differential cleavage of the KapB mRNA, we conducted Northern blot analysis for the KapB full-length mRNA, as well as the KapB mRNA 3′ fragments that result from Drosha-mediated cleavage. This analysis showed that, as expected from increased lytic transcription, both the full-length mRNA and Drosha cleavage fragments increased during the course of lytic infection. However, the kinetics of accumulation of these Drosha substrates and products were different. During latency and at early times postlytic induction (up to 12 h) the ratio of full-length KapB mRNA:cleaved KapB fragment RNAs remains constant. Then, starting at ∼24 h postlytic induction, the ratio dramatically increases until the late times of lytic replication (greater than 48 h postinduction) (Fig. 4 B and C). The kinetics of induction of miRs K12-10 and K12-12 more closely match the KapB mRNA cleavage fragments, which might be expected because all are derivatives of Drosha cleavage products. Interestingly, the ratio of the faster-migrating KapB mRNA cleavage fragment (corresponding to cleavage of premiR-K12 or both premiR K12-12 and premiR K12-10) to the slower-migrating cleavage fragment (corresponding to cleavage of premiR K12-10 alone) inverts during the course of infection, consistent with limiting Drosha activity and premiR K12-10 being the preferred Drosha substrate (Fig. 4 B and D). Combined, these data support a greater role for Drosha in regulating KapB mRNA levels during latent infection and at early times postlytic induction. Therefore, several lines of evidence strongly suggest that Drosha activity becomes limiting during the course of lytic replication, including: (i) decreasing Drosha protein levels, (ii) altered ratios of Drosha substrate and products, and (iii) increasing proportions of products from Drosha-favored substrates over less-efficiently cleaved substrates. Thus, Drosha-mediated cleavage differentially regulates KapB expression in latent versus lytic infection.

Next, we tested whether the differences in Drosha levels we observe are indeed caused by viral gene products and lytic replication. To control for possible off-target effects from the drug regimen used to induce lytic replication in the latently infected PEL B cells, we measured Drosha protein levels in the presence of an shRNA specific to RTA (the master lytic switch transcription factor). Transfection of TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells with the RTA shRNA (but not an irrelevant control shRNA) before induction of lytic replication resulted in decreased levels of RTA (Fig. 4E). In these cells, there was a marked increase in Drosha levels, implying that viral gene products and lytic replication are responsible for the reduced Drosha levels observed. The magnitude of these results is likely an underestimate, because even with shRNA-mediated knockdown of RTA, a noticeable, albeit less robust increase in RTA levels is still observed. To determine if lytic replication decreases Drosha levels in a different model of infection (20), primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were used. Although B cells are a prominent reservoir of latent infection for KSHV, KS lesions are predominantly composed of endothelial cells. De novo latent infection of HUVECs did not alter Drosha levels (Fig. 4F). However, coinfection of KSHV with an adenovirus RTA expression vector (adRTA), resulted in induction of lytic replication and a decrease in Drosha levels (Fig. 4F). Importantly, infection with adRTA alone, or coinfection of KSHV and control adenovirus expressing the irrelevant viral protein vGPCR, had little effect on Drosha levels. These results clearly show that KSHV lytic infection of PEL B cells or endothelial cells results in decreased Drosha levels.

Discussion

Determining how viruses control their own gene expression is key to understanding the pathogenesis associated with infection. Previously, the only known biological activities of Drosha involved the biogenesis of miRNAs (either directly converting pre-miRNAs to miRNAs, or indirectly by Drosha regulating the mRNA levels of DGCR8). Our work extends the biological activities of Drosha to regulation of viral gene expression. At the same time, our results suggest previously unanticipated cis-regulatory functions are likely for some of the over 200 viral pre-miRNAs that have been discovered. Deciphering the functions of viral miRNAs is currently an area of intense interest from multiple laboratories. There is an increasing appreciation that the functions of some viral miRNAs include the trans targeting of host or viral mRNAs (7). However, other functions remain possible, especially given that the majority of viral miRNAs have no known function. Here we demonstrate that KSHV pre-miRNAs, premiRs K12-10 and K12-12, are negative regulatory elements that function in cis within the KapB mRNAs. We stress that our results in no way rule out additional functions for the derivative miRNAs miRs K12-10 and K12-12. [In fact, miR K12-10 has recently been shown to target the host transcript TWEAKR (21)]. We show that Drosha directly cleaves KapB transcripts, resulting in decreased KapB protein levels in latently infected cells. Interestingly, this regulation decreases during the course of lytic infection concomitant with a decrease in Drosha protein steady-state levels.

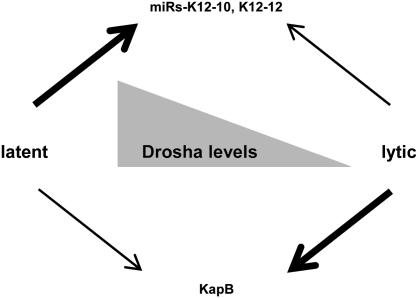

What mechanism accounts for the decreased Drosha levels that are observed during lytic infection? We have shown that the mRNA steady-state levels of Drosha decrease during lytic replication and we have determined that the half-life of Drosha protein is ∼4 h in latently or lytically infected cells (Fig. S4). Given that KSHV is known to induce host shut-off by causing degradation of host mRNAs (22), we hypothesized that viral-mediated global turnover of mRNAs combined with the relatively short half-life of Drosha protein accounts for at least some of the turnover observed. In support of this, we show that knockdown of SOX, a key effector of KSHV-mediated host shut-off, results in increased levels of Drosha and decreased levels of KapB mRNA during lytic infection (Fig. S4B). The most parsimonious interpretation of these combined observations is that lytic infection triggers a decrease in Drosha protein levels, resulting in decreased Drosha-mediated cleavage of KapB mRNA (Fig. 5). Thus, in addition to differences in transcription, differential mRNA cis-regulation contributes to the robust differences in KapB protein present in cells undergoing latent versus lytic infection.

Fig. 5.

Model for Drosha-mediated regulation of viral gene expression. Efficient miRNA production is favored over KapB expression during latency, but the opposite occurs during lytic infection. Drosha activity is highest during latent infection and low during lytic infection. Along with previously established changes in transcriptional activity, Drosha-mediated cis-regulation of the KapB mRNA transcripts contributes to the low levels of KapB protein that are observed during latency. During lytic infection, the degree of Drosha-mediated regulation of KapB levels diminishes.

What advantage is there in tying the biogenesis of KapB inversely to Drosha activity? KS, perhaps even more so than many other cancers, is a disease of cytokine deregulation. Although the advantage of increased cytokine signaling to the virus replication cycle is not fully understood, it is clear that KSHV encodes multiple gene products that either are themselves cytokines or have the ability to induce various host cytokines. KapB induces p38 Map kinase signaling that can result in increased cytokine production (17). However, others have suggested (14), and we have confirmed, that prolonged high expression of KapB is cytotoxic (Fig. 3). It is possible that high cytokine levels are beneficial during lytic replication when the cells are destined to die anyway, but that high expression of KapB during latency would reduce viral fitness. Clearly, low-level expression of KapB has been selected for during latent infection and must be advantageous to the virus. Thus, the virus has evolved multiple mechanisms, including differential transcriptional regulation and mRNA cis-regulatory elements (dependent on Drosha-mediated cleavage), to ensure consistently low expression of KapB in latency and yet allow robust expression during lytic replication.

These findings raise the question of whether viral utilization of Drosha activity serves an added advantage over other possible mRNA-negative regulatory proteins. For example, Drosha activity may serve as a sentinel for cellular states in which the virus would benefit from increased KapB levels during latent infection. In this regard, it is interesting to note that another viral protein, EBV BHRF-1, is known to have pre-miRNAs embedded within the 3′ UTR of its mRNA (23). BHRF-1 is expressed during some forms of latent infection and has a well-defined mechanism of preventing cell death in the presence of proapoptotic stressors (24). Our results predict that, like KapB, BHRF1 would be expressed at higher levels when Drosha activity is low. Thus, presumably there are cellular physiological states during latency when both viruses benefit from increased expression of these stress-responsive proteins. To better understand why divergent herpesviruses apparently use cis-regulatory elements that are dependent on Drosha activity, it will be imperative to determine what host signaling pathways regulate Drosha activity, and what functions are associated with host transcripts directly regulated by Drosha.

In summary, we have shown that a viral mRNA transcript is directly regulated by Drosha cleavage, and that the degree of this regulation is variable during lytic or latent infection. This finding expands the known functions of Drosha to regulation of viral gene expression and sets the stage for uncovering other novel functions of Drosha in addition to its established role in miRNA biogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Viral Infection.

Near global lytic replication in TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells (25) was induced by the addition of Doxycyline and TPA (26). Preparations of KSHV viral stocks (27) and de novo KSHV infections and adenoviral RTA expression vector superinfections (22) were performed as previously described (22).

Vector Construction and Transfection.

The KapB expression vectors used in this article were made by cloning the wild-type KapB 3′ UTR (accession: NC_009333.1) or the miRNA-deleted versions of the KapB 3′ UTR (without miR K12-10/12 5p and 3p sequences) into the pCR3.1- HA-KapB vector. The luciferase reporters were made by cloning the KapB 3′ UTR into the pMSCV-Luc2CP vector (28). To express miR K12-10 and miR K12-12, the full-length KapB 3′ UTR was cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector. Previously characterized Drosha, DGCR8, or SOX-specific siRNAs were used to knockdown Drosha, DGCR8, and SOX levels (9, 22).

Luciferase Assay.

HEK293T cells were cotransfected with pMSCV-Luc2CP-KapB 3′ UTR reporters and pcDNA3.1- RLuc (Renilla) vector (28). Firefly luciferase activity is normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

Immunoblot Analysis.

Cells were lysed and analyzed via SDS PAGE/immunoblot analysis as described (29).

Northern Blot Analysis.

Small RNA Northern blot analysis was performed as described (30). Radioactive probes for analysis of longer RNAs were generated by random prime labeling and small RNA blots were probed with radioactive antisense nucleotides.

Flow Cytometry and Annexin V Dying Cell Assay.

To identify dying cells, TREx-RTA BCBL-1 cells were collected 48 h after transfection. Cells were washed with PBS buffer and resuspended in buffer containing labeled Annexin V and propidium iodide and assayed via flow cytometry. Dead cells and subcellular debris, as determined from aberrant forward/side scatter profiles, were eliminated from further analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Britt Glaunsinger, Craig McCormick, Don Ganem, V. Narry Kim, Jae Jung, and Ren Sun for reagents, and the members of the C.S.S. laboratory for comments regarding this manuscript. This work was supported by Grants R01AI077746 from the National Institutes of Health and RP110098 from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, and a University of Texas at Austin Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1105799108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Liu Y, Wimmer E, Paul AV. Cis-acting RNA elements in human and animal plus-strand RNA viruses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:495–517. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman PM. Chromatin organization and virus gene expression. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216:295–302. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaniv M. Small DNA tumour viruses and their contributions to our understanding of transcription control. Virology. 2009;384:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boss IW, Renne R. Viral miRNAs: Tools for immune evasion. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skalsky RL, Cullen BR. Viruses, microRNAs, and host interactions. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:123–141. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan CS. New roles for large and small viral RNAs in evading host defences. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:503–507. doi: 10.1038/nrg2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grundhoff A, Sullivan CS. Virus-encoded microRNAs. Virology. 2011;411:325–343. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim VN. MicroRNA biogenesis: Coordinated cropping and dicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:376–385. doi: 10.1038/nrm1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han J, et al. Posttranscriptional crossregulation between Drosha and DGCR8. Cell. 2009;1361:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chong MM, et al. Canonical and alternate functions of the microRNA biogenesis machinery. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1951–1960. doi: 10.1101/gad.1953310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shenoy A, Blelloch R. Genomic analysis suggests that mRNA destabilization by the microprocessor is specialized for the auto-regulation of Dgcr8. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganem D. Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated Herpesvirus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. 5th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Speck SH, Ganem D. Viral latency and its regulation: Lessons from the gamma-herpesviruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;81:100–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadler R, et al. A complex translational program generates multiple novel proteins from the latently expressed kaposin (K12) locus of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol. 1999;73:5722–5730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5722-5730.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang PJ, et al. Open reading frame 50 protein of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus directly activates the viral PAN and K12 genes by binding to related response elements. J Virol. 2002;76:3168–3178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3168-3178.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Komatsu T, Dezube BJ, Kaye KM. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K12 transcript from a primary effusion lymphoma contains complex repeat elements, is spliced, and initiates from a novel promoter. J Virol. 2002;76:11880–11888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.11880-11888.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCormick C, Ganem D. The kaposin B protein of KSHV activates the p38/MK2 pathway and stabilizes cytokine mRNAs. Science. 2005;307:739–741. doi: 10.1126/science.1105779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan CS, Cullen BR. Non-coding Regulatory RNAs of the DNA Tumor Viruses. In: Damania B, Pipas JM, editors. DNA Tumor viruses. New York: Springer Science; 2009. pp. 645–682. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renne R, et al. Lytic growth of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat Med. 1996;2:342–346. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grossmann C, Podgrabinska S, Skobe M, Ganem D. Activation of NF-kappaB by the latent vFLIP gene of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is required for the spindle shape of virus-infected endothelial cells and contributes to their proinflammatory phenotype. J Virol. 2006;80:7179–7185. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01603-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abend JR, Uldrick T, Ziegelbauer JM. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis receptor protein (TWEAKR) expression by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNA prevents TWEAK-induced apoptosis and inflammatory cytokine expression. J Virol. 2010;84:12139–12151. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00884-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glaunsinger B, Ganem D. Lytic KSHV infection inhibits host gene expression by accelerating global mRNA turnover. Mol Cell. 2004;13:713–723. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeffer S, et al. Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science. 2004;304:734–736. doi: 10.1126/science.1096781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly GL, et al. An Epstein-Barr virus anti-apoptotic protein constitutively expressed in transformed cells and implicated in burkitt lymphomagenesis: The Wp/BHRF1 link. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000341. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura H, et al. Global changes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated virus gene expression patterns following expression of a tetracycline-inducible Rta transactivator. J Virol. 2003;77:4205–4220. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4205-4220.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arias C, Walsh D, Harbell J, Wilson AC, Mohr I. Activation of host translational control pathways by a viral developmental switch. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000334. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bechtel JT, Liang Y, Hvidding J, Ganem D. Host range of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in cultured cells. J Virol. 2003;77:6474–6481. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6474-6481.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seo GJ, Fink LH, O'Hara B, Atwood WJ, Sullivan CS. Evolutionarily conserved function of a viral microRNA. J Virol. 2008;82:9823–9828. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01144-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin YT, et al. Small RNA profiling reveals antisense transcription throughout the KSHV genome and novel small RNAs. RNA. 2010;16:1540–1558. doi: 10.1261/rna.1967910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McClure LV, Lin YT, Sullivan CS. Detection of viral microRNAs by Northern blot analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;721:153–171. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-037-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakakibara S, Ueda K, Chen J, Okuno T, Yamanishi K. Octamer-binding sequence is a key element for the autoregulation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF50/Lyta gene expression. J Virol. 2001;75:6894–6900. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6894-6900.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.