Abstract

Ranolazine is an FDA-approved anti-anginal agent. Experimental and clinical studies have shown that ranolazine has anti-arrhythmic effects in both ventricles and atria. In the ventricles, ranolazine can suppress arrhythmias associated with acute coronary syndrome, long QT, heart failure, ischemia, and reperfusion. In atria, ranolazine effectively suppresses atrial tachyarrhythmias and fibrillation (AF). Recent studies have shown that the drug may be effective and safe in suppressing AF when used as a pill-in-the pocket approach, even in patients with structurally compromised hearts, warranting further study. The principal mechanism underlying ranolazine’s antiarrhythmic actions is thought to be primarily via inhibition of late INa in the ventricles, and via use-dependent inhibition of peak INa and IKr in the atria. Short and long term safety of ranolazine has been demonstrated in the clinic, even in patients with structural heart disease. This review summarizes the available data regarding the electrophysiological actions, and anti-arrhythmic properties of ranolazine in preclinical and clinical studies.

Keywords: Antiarrhythmic drugs, pharmacology, electrophysiology, atrial fibrillation, ventricular arrhythmias, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, Bradyarrhythmias

A. Ion Channel Currents

Ranolazine is known to inhibit a number of ion currents (e.g., INa, IK, ICa, L) that are important for the genesis of the transmembrane cardiac action potential.1–5 Table 1 summarizes the concentrations of ranolazine that cause 50% inhibition (IC50 values) of the various ion currents. In ventricular myocytes, the two ion currents most sensitive to ranolazine are the late/sustained/persistent sodium current (late INa) and the rapidly activating delayed-rectifier potassium current (IKr). In atrial myocytes, in addition to block of IKr and late INa, ranolazine inhibits the early or peak sodium channel current (peak INa).4, 5

Table 1.

Summary of the potency of ranolazine to inhibit cardiac ion channel currents in canine left ventricular myocytes

| Ion Currents | IC50 values (μM) |

|---|---|

| A. Inward | |

| Peak INa | 294a |

| Late INa | 5.9 |

| Peak ICa,L | 296 |

| INa-Ca (reverse mode) | 91 |

| B. Outward | |

| IKr | 11.5 |

| IKs | 17% at 30 μM |

| IK1 | No effect |

| ITo | No effect |

A.1 Peak and Late Sodium Current (INa)

The inhibition by ranolazine of INa, peak and late, is voltage- and frequency-dependent, tissue-specific (atria vs. ventricles), and possibly species-specific. The differential potencies of ranolazine to inhibit peak and late INa have been characterized in canine ventricular myocytes isolated from non-failing and failing hearts3 and in human embryonic kidney cell line HEK-293 expressing the human NaV1.5 gene.6 Ranolazine inhibits peak INa (tonic block) in ventricular myocytes from non-failing hearts and failing hearts with similar IC50 values (potencies) of 294 and 244 μM, respectively. In comparison, the potency of ranolazine to inhibit late INa (tonic block) in myocytes from failing hearts is approximately 6.5 μM,3 a value similar (5.85 μM) to that reported by Antzelevitch et al.1 in canine ventricular myocytes isolated from normal hearts (Table 1). Thus, in canine ventricular myocytes, tonic block of late INa is observed at concentrations of ranolazine that are about 30 to 38-fold lower than required to cause tonic inhibition of peak INa. In ventricular myocytes of mice expressing the ÄKPQ mutation (LQT-3), ranolazine was found to inhibit peak and late INa with potencies of 135 μM and 15 μM, respectively, resulting in a differential potency of approximately 9-fold.7 Whether species and/or experimental conditions account for the differential potency ratio of ranolazine to inhibit peak vs. late INa (30 to 38-fold in canine vs. 9-fold in the LQT3 mouse) is not known. Whereas ranolazine inhibition of late INa is well within the the therapeutic range of concentrations of 2 to 8 μM, inhibition of peak INa in the ventricles occurs well beyond the therapeutic range.1, 8

In contrast to the lower potency of ranolazine to block peak INa in ventricular cells, the drug potently inhibits peak INa in atrial cells.4, 6 Ranolazine blocks late INa in atrial myocytes as well.5

A comprehensive study of the concentration and frequency-dependent inhibition (or use-dependent block; UDB) of peak and late INa by ranolazine in human wild type (WT) and LQT3 mutant (R1623Q) NaV1.5 channels stably expressed in HEK-293 cells has been carried out.9, 10 The potencies of ranolazine to block peak INa and late INa increase with the stimulating frequency, but the selectivity of ranolazine for inhibiting late relative to peak INa is maintained at both low (0.1 Hz, tonic block) and high frequencies (5.0 Hz, UDB). In WT, the IC50 values of ranolazine to reduce peak INa, at stimulating frequencies of 0.1 and 5.0 Hz are 427±35.21 μM and 154.01±17.81 μM respectively, whereas in the R1623Q mutant, they are reported to be 95.32±2.25 μM and 24.60±2.46 μM, respectively.10 The endogenous late INa of the R1623Q mutant, which is 2- to 3-fold greater than in the WT, was inhibited by ranolazine with IC50 values of 7.45±0.11 μM and 1.94±0.01 μM at 0.1 Hz and 5.0 Hz, respectively.10 These findings suggest that inhibition of late INa by ranolazine will be greater at faster (i.e., tachycardia) than at normal heart rates in pathological conditions in which this current is augmented. The inhibition of peak INa by ranolazine is also dependent on membrane potential. In HEK-293 cells expressing NaV1.5, the IC50 values for ranolazine to reduce the amplitude of peak INa were 428±35 μM, 209±9 μM and 35±5 μM at holding potentials −120 mV, −100 mV and −80 mV, respectively.9 Hence, inhibition of peak INa by ranolazine is expected to be greater in depolarized myocytes.

Ranolazine is structurally similar to some local anesthetics (LA) and appears to interact with the same binding site in the inner pore of the cardiac sodium channel (NaCh).7 This is supported by the finding that the effects of ranolazine to inhibit peak and late INa are significantly reduced by mutation of residue F1760 in the LA binding site in the S6 helical transmembrane segment of domain IV of the NaCh.7

A.2 Rapidly Activating Delayed Rectifying K+ Current (IKr)

IKr encoded by the human Ether-à-go-go-Related Gene (hERG) plays a major role in cardiac repolarization. Inhibition of this current is associated with prolongation of the cardiac action potential and QT interval. In canine left ventricular (LV) myocytes, ranolazine causes a concentration-dependent inhibition of IKr with an IC50 of 11.5 μM (Table 1). Inhibition of IKr by ranolazine explains the effect of the drug to prolong ventricular and atrial action potential (AP) duration (APD) and the small QTc interval prolongation observed in clinical trials.11 In HEK-293 cells stably expressing hERG K+ channels (IhERG), ranolazine causes a time- and voltage-dependent, but frequency independent block of peak tail IhERG at −20 mV with an IC50 of 12 μM,12 nearly identical to that of IKr in canine ventricular myocytes.1 The development and recovery from IhERG block by ranolazine has rapid kinetics.12 IhERG block develops within milliseconds (<80 msec), depending on the concentration of ranolazine, and recovery from block is complete within 200 msec at −80 or −100 mV.12 In comparison, other IKr blockers (e.g., E-4031, dofetilide) have slow kinetics for the development of inhibition (hundreds of milliseconds), which is frequency-dependent, and recovery from block, is slow or irreversible.13

A.3 L-Type Calcium Current (ICa,L)

Ranolazine is a weak inhibitor of ICa,L. In canine ventricular myocytes, ranolazine inhibits peak and late ICa, L with and IC50 of 296 and 50 μM, respectively (Table 1). Within the therapeutic concentration range of 2 to 8 μM, ranolazine reduces late ICa, L by 25 to 30%.1 In guinea pig ventricular myocytes, ranolazine at concentrations of 3 and 30 μM reduced the amplitude of ICa, L by 8±2% and 13±3% respectively.14 In another study in guinea pig myocytes 10 and 100 μM ranolazine caused a small 2.4% and 17.3% inhibition of the basal ICa, L.15 In the same study, 10 μM ranolazine inhibited isoproterenol-stimulated ICa, L by 47.6%,15 likely due to a β-adrenergic receptor blocking activity of ranolazine.16 Consistent with these relatively weak effects on ICa-L, the effects of ranolazine on Ca2+-dependent cardiac, vascular and smooth muscle functions, such as contractility, atrioventricular (AV) nodal conduction, heart rate and direct vasodilation are small or not observed at concentrations ≤ 10 μM.14

A.4 Other Ion Currents

In canine and guinea pig ventricular myocytes, ranolazine at concentrations as high as 100 μM has no effect on IK1,1, 14 which explains the lack of effect of ranolazine on the resting membrane potential of ventricular and atrial myocytes.1, 4, 14 Likewise, ranolazine has a minimal effect on the transient outward potassium current (Ito), causing approximately a 10±2% reduction in the amplitude of Ito at a concentration of 50 μM1 and has no significant effect on IKur in canine atrial cells (Zygmunt and Antzelevitch, unpublished observation).

The Na-Ca exchange current (INCX) of canine ventricular myocytes is weakly inhibited by ranolazine with a potency of 91 μM (Table 1). In a recent abstract Soliman et al.17 reported that in intact neonatal rat cardiac myocytes, ranolazine directly inhibits the reverse mode of NCX1.1. In the same study, the IC50 of ranolazine to inhibit the reverse mode of recombinant NCX1.1 was 40.8±3.9 μM. To our knowledge, the effects of ranolazine on If, ICa-T and IK-ATP have not been determined. However, based on the known effects of ranolazine on cardiac action potentials and heart function (e.g., APD duration, normal automaticity), it is unlikely that ranolazine will have a major effect on these currents.

In summary, considering that the mean peak plasma concentration of ranolazine achieved at the two FDA approved doses, 500 and 1,000 mg bid, are 1,126 ng/mL (2.6 μM) and 2,477 ng/mL (5.8 μM), late INa, and IKr are the currents most likely to be significantly inhibited by ranolazine in ventricular myocytes, although inhibition of late ICa-L may also contribute to ranolazine’s electrophysiological actions. In atrial cells, the electrophysiological effects of ranolazine are likely to be mediated primarily via inhibition of peak INa and IKr, but inhibition of late INa is also likely to contribute.

B. Transmembrane Ventricular and Atrial Action Potential

B.1 Resting Membrane Potential (RMP)

Ranolazine has no effect on the RMPs of canine and guinea pig ventricular myocytes, guinea pig papillary muscles, canine Purkinje fibers or canine atrial preparations,1, 4, 14 which is consistent with the lack of effect of the drug on inward rectifier potassium channel current (IK1).

B.2 Action Potential Amplitude, Overshoot, and Rate of Rise of Upstroke (Vmax)

In canine epicardial (Epi) and M cells as well as in Purkinje fibers, ranolazine at concentrations ≤50 μM has minimal or no effect in AP amplitude and overshoot,1 but does depress AP amplitude and Vmax at higher concentrations in ventricular and Purkinje preparations.1 In contrast, ranolazine significantly depresses Vmax in atria at concentrations within the therapeutic range, particularly at rapid activation rates (Figure 1).4, 18

Figure 1.

Ranolazine produces a much greater rate-dependent inhibition of the maximal action potential upstroke velocity (Vmax) in atria than in ventricles. Shown are Vmax and action potential (AP) recordings obtained from coronary-perfused canine right atrium and left ventricle before (C) and after ranolazine (10 μM). Ranolazine prolongs late repolarization in atria, but not ventricles (due to IKr inhibition 23) and acceleration of rate leads to elimination of the diastolic interval in the atrium. Reprinted from J Electrocardiol, Vol 42, Antzelevitch C, Burashnikov A, Atrial-selective sodium channel block as a novel strategy for the management of atrial fibrillation, 543–548, 2009, with permission from Elsevier.

B.3 Action Potential Duration (APD)

The effect of ranolazine on APD of ventricular myocytes is mediated by its effect to inhibit late INa (IC50 = 6 μM) and IKr (IC50 = 12 μM). Because these two currents have opposing effects on APD, the net effect of ranolazine on APD depends on their relative contribution to repolarization at any given time/condition, and on the cell type (e.g., ventricular Epi-, M cell, Purkinje fiber, atrial crista terminalis, pectinate muscle, or pulmonary vein (PV)).1, 4, 18 In M cells and Purkinje fibers, where late INa and APD are relatively large and long, respectively, ranolazine causes a concentration-dependent abbreviation of APD at slow pacing rates. When late INa is increased and APD is prolonged, as in myocytes isolated from the LV of ÄKPQ-LQT3, failing or hypertrophic hearts (HF and LVH), or cells exposed to ATX-II, veratridine, or angiotensin II,19 ranolazine abbreviates APD. Similarly, when IKr is inhibited (e.g., by drugs, hERG mutations) and APD is prolonged, the physiologic late INa, although small, contributes significantly to ventricular repolarization, so that its inhibition by ranolazine results in abbreviation of APD.20 Under these conditions, the effects of ranolazine to inhibit late INa are not only important for regulation of APD, but also for dispersion of ventricular repolarization and beat-to-beat variability of APD. The effect of ranolazine to prolong epicardial but abbreviate M cell APD results in a reduction of transmural dispersion of repolarization (TDR).1 This effect of ranolazine is particularly pronounced when TDR is augmented following exposure to IKr blockers such as E-4031 or late INa agonists such as ATX-II.20

Reduced repolarization reserve due to an enhanced late INa, reduced IKr or both, accompanying pathological conditions (e.g., HF, LVH) is associated with a marked increase in beat-to-beat variability of APD in isolated ventricular myocytes, isolated perfused hearts and whole heart in situ. Ranolazine has been shown to reduce the beat-to-beat variability of APD under these conditions.21 At heart rates equivalent to resting sinus rhythm (in canine CL ~ 500 ms), ranolazine causes no significant changes in APD50–90 in canine LV M cell and epicardial preparations, while still causing significant abbreviation of APD50–90 in Purkinje fibers.4

Ranolazine significantly prolongs atrial but not ventricular APD90 at a CL of 500 ms (Figure 1).4 It is noteworthy that IKr inhibition with E-4031 also produces atrial-selective prolongation of APD and effective refractory period at normal and rapid activation rates.22, 23

C. Refractoriness and Excitability

C.1 Effective refractory period (ERP), post-repolarization refractoriness (PRR), diastolic threshold of excitation (DTE), and Conduction time (CT)

Ranolazine prolongs ERP, increases DTE, and slows conduction velocity exclusively or predominantly in atria.4, 18 The ranolazine-induced prolongation of atrial ERP is due both to prolongation of APD and development of PRR. In the ventricles, ranolazine does not induce PRR. Atrial-selective prolongation of ERP and increased DTE as well as slowing of conduction velocity have also been demonstrated in in vivo pigs.24, 25 These changes in DTE, CT, PRR, and Vmax are all due to ranolazine-mediated depression of peak INa. A number of factors are thought to contribute to the atrial selectivity of ranolazine to suppress sodium channel (NaCh)-mediated parameters, including a more depolarized RMP in atria, a more negative half-inactivation voltage (V0.5), and a more gradual phase 3 of the atrial action potential that leads to reduction or elimination of the diastolic interval in atria, particularly at rapid activation rates (Figure 1, for review see 26).

D. Antiarrhythmic Properties and Antiarrhythmic Mechanisms

D.1 Ventricles

Arrhythmogenesis associated with reduced repolarization reserve caused by an increased late INa, reduced IKr or a combination of both, is effectively suppressed by ranolazine (Figure 2; see above Section B.3). Besides prolonging APD and destabilizing repolarization, enhanced late INa increases Na+ influx and, and via NCX, increases intracellular Ca2+ (Ca i2+) resulting in calcium overload. Abnormal Ca i2+ handling and Cai2+-transients lead to spontaneous release of Ca2+ from SR, transient inward current (ITi), delayed after depolarizations (DADs), and triggered activity. These arrhythmogenic changes occur when late INa is increased by congenital or acquired pathophysiological conditions and are reversed or prevented by ranolazine.27 In ventricular myocytes from canine failing hearts, prolonged Ca i2+-transients are abbreviated and spontaneous Ca i2+ release are suppressed by ranolazine and tetrodotoxin.28, 29 These results suggest that inhibition of late INa-induced dysregulation of Cai2+ homeostasis, manifested by spontaneous release of Ca++ from SR, ITi, and DADs are likely to contribute to the antiarrhythmic effects of ranolazine. 27–29

Figure 2.

Ranolazine (200 μg/kg/min) abbreviates ventricular repolarization and suppresses Torsade de Pointes (TdP) arrhythmias in anesthetized rabbit. Shown are representative ECG and left ventricular endocardial monophonic action potential (MAP) tracings. Repolarization was prolonged and TdP was induced by the combination of methoxamine (15 μg/kg/min) and clofilium (100 ng/kg/min). Modified with permission from Wang WQ, Robertson C, Dhalla AK, Belardinelli L. Antitorsadogenic effects of ({+/−})-N-(2,6-dimethyl-phenyl)-(4[2-hydroxy-3-(2-methoxyphenoxy)propyl]-1-piperazine (ranolazine) in anesthetized rabbits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 325(3):875–881.

Results of studies conducted in both in vitro and in vivo models of arrhythmia have confirmed the antiarrhythmic properties of ranolazine. In guinea pig and rabbit isolated perfused hearts,30, 31 ranolazine has been shown to suppress beat-to-beat variability of APD, dispersion of ventricular repolarization, EADs, and ventricular tachycardia (VT) induced by drugs that block IKr. In the rabbit model of Torsade de Pointes (TdP) described by Carlsson et al.,32 ranolazine was found to terminate and prevent recurrence of TdP induced by clofilium, an IKr blocker (Figure 2).33 Antoons et al.21 reported that in the canine chronic AV block model, TdP-induced by dofetilide, was suppressed, and short-term beat-to-beat variability of ventricular repolarization was reduced by ranolazine. Indeed, ranolazine has been reported to suppress TdP in LQT1, LQT2 and LQT3 experimental models of the long QT syndrome (LQTS) via its actions to reduce TDR.1, 34–38 The observed “anti-torsadogenic” effect of ranolazine can be explained by inhibition of the physiologic late INa that albeit small, becomes a major contributor of ventricular repolarization when IKr is inhibited.20 Additional evidence for the antiarrhythmic activity of ranolazine are the findings that in closed-chest anesthetized pigs instrumented for programmed electrophysiological testing, ranolazine at concentrations of ~9 μM significantly prolonged right ventricular effective refractory period, increased the threshold for induction of repetitive ventricular extrasystoles (RE) and ventricular fibrillation (VF) but not the threshold for defibrillation (DFT).39 In the same study, ranolazine also significantly reduced, by ~40%, the ventricular vulnerable period width for induction of extrasystoles. These data raise the possibility that ranolazine may be effective in suppressing ventricular arrhythmias observed in the setting of myocardial ischemia. Indeed, ranolazine has been reported to reduce ischemia-reperfusion induced ventricular premature beats, VT, and VF in an anesthetized rat model of transient (5 min) ligation of left coronary artery, followed by reperfusion.40 Whether inhibitions of late INa, IKr, and/or peak INa alone or combined contribute to the anti-arrhythmic effects of ranolazine on ventricular vulnerability for REs and VF in the intact porcine heart, and ischemia-reperfusion induced VT and VF in rats is not clear. However, recently Morita et al.41 reported that, in isolated-perfused hearts from aged rats, ranolazine effectively suppresses pacing-induced re-entrant AF and EAD-mediated multifocal VF, and provided strong evidence that this effect was due to inhibition of late I Na. Another recent study demonstrated a potent antifibrillatory effect of ranolazine during severe coronary stenosis in the intact porcine model.42 This action appears to be due primarily to block of late INa and independent of coronary flow changes. There is now substantial literature describing the antiarrhythmic properties of ranolazine in various ventricular preparations, experimental conditions, and models of ventricular arrhythmia, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of pathological conditions, pharmacological agents, toxins known to elicit ventricular arrhythmias* that are suppressed by ranolazine

| Reactive Oxygen Species41, 70, 71 |

| Class III antiarrhythmic agents (e.g., dofetilide, sotalol, amiodarone)1, 21, 30, 33, 72–75 |

| Non-cardiovascular drugs that cause TdP (moxifloxacin, cisapride, etc.)31, 35 |

| Late INa agonists (toxins and pharmacological agents2, 29, 30, 72, 75, 76 |

| Pharmacological agents (e.g., bayK 8644, Ouabain, Angiotensin II19, 77, 78 |

| High Co2 (e.g., acidosis)79 |

| LQT2 iPS cell80 |

| Ventricular myocytes from failing hearts (ischemia- or tachycardia-induced HF)3, 28, 81 |

| Ischemic hearts (pre-clinical) 40 |

| Ischemic and non-ischemic hearts (clinical)58, 82–84 |

| Severe acute coronary artery stenosis (pre-clinical)42 |

Includes ventricular ectopic beats and tachycardia, beat-to-beat variability of ventricular repolarization, abnormal automaticity, and triggered activity caused by early and delayed afterdepolarizations.

In summary, it is becoming increasingly clear that a pathologic increase in late INa contributes to development of arrhythmias via three major mechanisms: a) enhanced abnormal automaticity, b) triggered activity (due to after depolarizations), and c) re-entry. Observed suppression of ventricular arrhythmias by ranolazine, within the therapeutic concentrations of 2 to 8 μM, could be primarily ascribed to its effect to inhibit late INa and to reduce Na+-dependent intracellular calcium overload in the ventricle. Inhibitions of IKr, and under special circumstances (short cycle-lengths and depolarized cells as during VF) peak INa, may contribute as well.

D.2 Atria

Ranolazine has been shown to terminate atrial arrhythmias and prevents their initiation in several experimental models.4, 18, 24 Ranolazine (10 μM) has been shown to be very effective in suppressing persistent vagally-mediated AF and preventing its induction in canine isolated coronary-perfused atria (Figure 3).4 Ranolazine also prevents the induction of β-adrenergically-mediated AF in coronary-perfused canine atria exposed to ischemia and reperfusion (Figure 3).4 In canine isolated pulmonary vein preparations, ranolazine (5–10 μM) suppresses the common triggers of AF initiation (i.e., DAD and late phase 3 EAD activity) (Fig. 4).18, 43 In isolated atrial guinea pig myocytes, DADs and EADs induced by an increase of late INa and automaticity induced by hydrogen peroxide (H202) are effectively suppressed by ranolazine.27, 44 Ranolazine (~9 μM) significantly shortens vagally-mediated AF in porcine hearts in vivo.24 Table 3 summarizes studies demonstrating an effect to ranolazine to suppress atrial arrhythmias in both experimental and clinical settings.

Figure 3.

Ranolazine suppresses AF and/or prevents its induction in two experimental models involving isolated canine arterially-perfused right atria. A: Persistent ACh (0.5 μM)-mediated AF is suppressed by ranolazine (10 μM). AF initially converts to flutter and then to sinus rhythm. B: ERP measured at a CL of 500 ms is 140 ms. Attempts to re-induce AF fail because ranolazine-induced depression of excitability leads to 1:1 activation failure soon after CL is reduced from 500 to 200 ms (right panel). C: Rapid-pacing induces non-sustained AF (48 sec duration) following ischemia/reperfusion plus isoproterenol (Iso, 0.2 μmol/L) (left panel). Ranolazine (5 μM) prevents pacing-induced AF due to 1:1 activation failure (right panel). In both models, ranolazine causes prominent use-dependent induction of PRR.

Reproduced with permission from Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Zygmunt AC, Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C. Atrium-selective sodium channel block as a strategy for suppression of atrial fibrillation: differences in sodium channel inactivation between atria and ventricles and the role of ranolazine. Circulation,116(13):1449–1457.

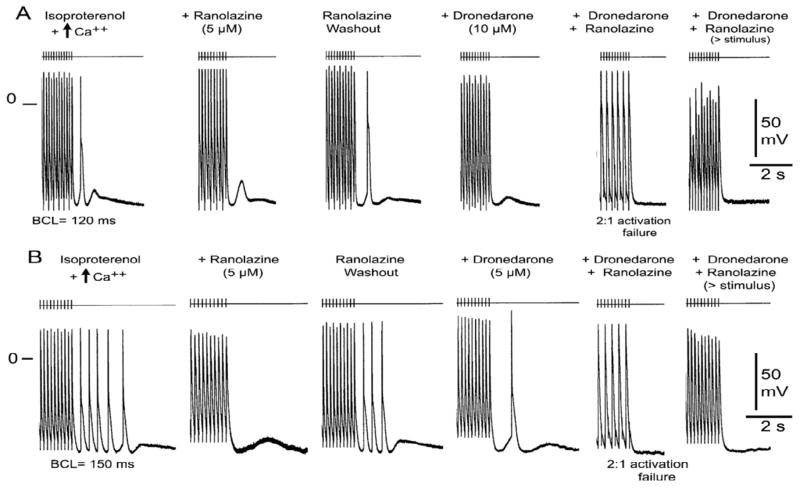

Figure 4.

Combination of ranolazine (5 μM) and dronedarone (10 μM) eliminates delayed afterdepolarization (DAD)-induced triggered activity in canine PV sleeve preparations. A: Isoproterenol (1 μM) and high calcium (5.4 mM) induce DAD and DAD-induced triggered activity. Ranolazine (5 μM) eliminates the triggered activity, but not the DAD. Washout of ranolazine restores the triggered response followed by a DAD. Dronedarone (10 μM) eliminates the triggered response, but the DAD persists. The combination of ranolazine and dronedarone eliminates all DAD activity and induces 2:1 activation failure; an increase of stimulus intensity restores 1:1 activation, but not the DAD. B: In another preparation, the same protocol yielded multiple triggered beats. Ranolazine is seen to abolish all of ectopic activity, but not the DAD, whereas dronedarone (5 uM) reduces the number of triggered responses. A single triggered beat followed by a DAD persists. The combination of ranolazine and dronedarone eliminates all DAD activity and induces 2:1 activation failure; an increase of stimulus intensity restores 1:1 activation, but not the DAD. Basic cycle length (BCL) = 120 ms (A) and 150 ms (B). Modified from J Am Coll Cardiol, Vol 56, Burashnikov A, Sicouri S, Di Diego JM, Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, Synergistic effect of the combination of dronedarone and ranolazine to suppress atrial fibrillation, 1216–1224, 2010 with permission from Elsevier.

Table 3.

Summary of atrial tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias suppressed by ranolazine.

| Vagally-mediated AF in isolated canine atria and in pig in vivo4, 24 |

| β-adrenergically-mediated AF in canine atria exposed to ischemia/reperfusion4 |

| DAD- and EAD-induced triggered activity in canine isolated PV18 and human RA trabeculae5 |

| DAD and EAD activity as well as automaticity in isolated atrial guinea pig myocytes27, 44 |

| EAD-induced atrial arrhythmias in LQT3 mouse85 |

| Bradyarrhythmia in LQT3 mouse76 |

| Bradyarrhythmias (clinical)58 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia (clinical)58 |

| New onset of AF (clinical)58 |

| Paroxysmal AF (clinical)59–61 |

| Post-operative AF (clinical)62 |

The antiarrhythmic mechanism underlying the effect of ranolazine to suppress AF includes several factors. The principal factor entails block of peak INa, which reduces excitability, thus leading to use-dependent prolongation of ERP, due to development of PRR. The net result is failure of rapid activation of the atria (Figure 3). The effect of ranolazine to prolong APD90 in atria, secondary to its action to block IKr, serves to synergize the effect of the drug to block peak INa by reducing the diastolic interval, during which the NaCh recovers from drug block (Figure 1). As a result of its action to block peak and late INa, ranolazine reduces intracellular calcium activity (Cai), thus suppressing DAD-and EAD-mediated triggers of AF (Figure 4).18

Recent studies conducted in canine coronary-perfused atrial and ventricular preparations have shown a remarkable synergism when a relatively low concentration of ranolazine (5 μM) is combined with either chronic amiodarone or acute dronedarone, leading to atrial-selective depression of INa-dependent parameters and effective suppression of AF (Figs.4 and 5).43, 45 Individually, dronedarone or a low concentration of ranolazine prevented the induction of AF in 17% and 29% of preparations, respectively. In combination, the 2 drugs suppressed AF and triggered activity and prevented the induction of AF in 9 of 10 preparations (90%). Thus, low concentrations of ranolazine and dronedarone produce relatively weak electrophysiological effects and weak suppression of AF when used separately but when combined exert potent synergistic effects, resulting in atrial-selective depression of sodium channel–dependent parameters and effective suppression of AF.

Figure 5.

Atrial-selective induction of post-repolarization refractoriness (PRR) by ranolazine (Ran), dronedarone (Dron) alone and in combination (PRR was approximated by the difference between effective refractory period (ERP) and action potential duration measured at 70% repolarization (APD70) in atria and between ERP and APD measured at 90% repolarization (APD90) in ventricles; ERP corresponds to APD70–75 in atria and to APD90 in ventricles.

A: Shown are superimposed action potentials demonstrating relatively small changes with dronedarone and ranolazine and their combination. B: Summary data of atrial-selective induction of PRR. Ventricular data were obtained from epicardium and atrial data from endocardial pectinate muscle (PM). n=7–8. * p<0.05 vs. respective control (C). † p<0.05 vs. washout. ‡ p<0.05 vs. Dron 10. # p<0.05 vs. respective ERP. ** - p<0.05 - change in ERP induced by combination of Ran and Dron (from washout) vs. the sum of changes caused by Ran and Dron independently (both from washout). CL = 500 ms. Reprinted from J Am Coll Cardiol, Vol 56, Burashnikov A, Sicouri S, Di Diego JM, Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, Synergistic effect of the combination of dronedarone and ranolazine to suppress atrial fibrillation, 1216–1224, 2010 with permission from Elsevier.

The role of late INa inhibition by ranolazine in the management of AF is less well understood. Normalization of repolarization by block of late INa under conditions of prolonged repolarization in ventricles (such as LQTS and HF) can be readily understood (as discussed above; see Figure 2). AF occurrence is commonly associated with a significant abbreviation of atrial repolarization. Under these conditions, a specific block of late INa is expected to further abbreviate APD, thus promoting AF. However, enhanced late INa has been reported in atrial myocytes from patients with chronic AF5, and prolonged atrial APD has been reported in a number of diseases associated with AF occurrence such as congestive HF,46 atrial dilatation47, 48 and LQTS.49 Furthermore, in murine hearts from ΔKPQ-SCN5A mice, prolonged atrial AP and repolarization is associated with atrial tachyarrhythmias and AF that can be reversed by flecainide via, most likely, inhibition of late INa.50, 51 AF initiation in these conditions may be prevented by abbreviation of APD by block of late INa. Thus, inhibition of late INa may contribute to suppression of AF triggers by reducing Cai, secondary to the decrease in intracellular sodium activity (Nai).46–49

D.3 Atrial–selective sodium channel block as a strategy for AF suppression

A property of antiarrhythmic agents to specifically or selectively inhibit ion channels in atria is desirable in the management of AF in order to minimize the risk of ventricular pro-arrhythmia. The discovery in 2007 of important distinctions between atrial and ventricular sodium channels4 led to the identification of atrial-selective sodium channel blockers, including ranolazine and amiodarone.43, 52, 53 In canine coronary-perfused atrial and ventricular preparations as well as superfused PV preparations, ranolazine depresses sodium channel-mediated parameters, including Vmax, DTE, CT, and induces PRR selectively in atria.4, 18 At concentrations causing little to no electrophysiological changes in ventricles (10 μM), ranolazine effectively suppresses AF in canine atria and DAD/EAD in PV preparations.4, 18 Available data indicate that agents that block INa with relatively rapid kinetics tend to be atrial-selective and with slow kinetics are not (for review see26). Current understanding of the those that block INa mechanisms of atrial selectivity of INa blockers as well as potential applications of atrial-selective INa block for AF rhythm control are discussed in detail in recent reviews.26, 53, 54

E. Clinical Studies

E.1 Safety of Ranolazine

In multiple clinical studies ranolazine has demonstrated a relatively good clinical safety profile.11, 55, 56 Despite its effect to block IKr and prolong the QT interval, ranolazine does not induce TdP arrhythmias and, in fact, suppresses long QT-related ventricular arrhythmias in all long QT experimental models tested, including LQT1, LQT2 and LQT3.21, 30, 33, 35 The principal protective mechanism of ranolazine against TdP is its potent inhibition of late INa, which opposes the APD- and TDR-prolonging effects of IKr block.35

Both acute and long-term treatment with ranolazine has been shown to be safe in patients, even in those with cardiac structural abnormalities, including severe acute coronary syndrome, history of myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure.55, 56 Ranolazine’s safety is due in large part to the atrial selectivity of its action to block peak INa.26, 54 Thus, the available data suggest that ranolazine can be safe and effective in suppressing a wide variety of cardiac arrhythmia syndromes.

E.2 Ventricular arrhythmias

Consistent with its action to block late INa in the ventricle, ranolazine has been shown to cause a dose-dependent abbreviation of the QTc interval in patients with the LQT3 type of the LQTS, a monogenic disorder in which the electrophysiologic phenotype is due to an increase in late INa 57 Ranolazine, at a plasma concentration of 2,074 ng/mL (~4 μM), caused a mean abbreviation of QTc ranging from 22 to 40 ms from time-matched baseline QTc values.57 Each 1,000 ng/mL of ranolazine (i.e., ~2 μM) was associated with a 24 ms QTc abbreviation, with no change in PR interval or QRS duration.57 The lack of effect of ranolazine on PR interval and QRS duration are in keeping with the findings that ranolazine, at therapeutic concentrations, does not significantly inhibit peak INa in the ventricle.

Although data from the MERLIN-TIMI 36 study failed to demonstrate efficacy in patients with non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE ACS), data from 6 days of continuous ECG monitoring showed that ranolazine significantly suppressed episodes of non-sustained VT of ≥ 8 beats (p<0.001).58 These findings are supportive of further studies specifically designed to address this hypothesis that ranolazine has antiarrhythmic effects in the ventricle.

E.3 Atrial arrhythmias

To date, no well controlled, large randomized studies have been conducted evaluating the effect of ranolazine to suppress atrial arrhythmias. In a secondary analysis from the MERLIN-TIMI 36 trial, ranolazine treatment was associated with a significant reductions of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias (p<0.001) as well as a 30% reduction in new onset AF (p=0.08). Subsequently, results of a number of small exploratory clinical studies have shown an anti-AF efficacy of ranolazine in termination of paroxysmal AF as well as in prevention of postoperative AF.59–62 In an exploratory (not placebo-randomized control) clinical study, ranolazine was found to be more effective than amiodarone in preventing post-operative AF (AF incidence was 15 vs. 25%, respectively).62

The “pill-in-the-pocket” method has long been utilized for the acute termination of paroxysmal AF on an out-of-hospital basis, using agents such as propafenone and flecainide.63 The “pill-in-the-pocket” approach has proved to be an effective (approx. 80% AF suppression), convenient, and a patient-friendly approach, but it has a limited application because agents like flecainide and propafenone are contraindicated in patients with structurally-compromised hearts, which comprise the majority of AF patients. Recent exploratory clinical studies suggest that a single dose of 2000 mg ranolazine may be effective as a “pill-in-the-pocket” approach, converting 77% of AF patients, including patients with structural cardiac abnormalities, with no significant adverse reactions.60, 61 Considering the safety of ranolazine in patients with structural heart disease,55, 56 the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach utilizing ranolazine may have a much wider applicability than previously used Class Ic antiarrhythmic agents (i.e., propafenone and flecainide). The results of these studies are encouraging, but larger and multicenter clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ranolazine in the management of patients with AF are needed.

Future Directions

Despite growing experimental and clinical evidence that ranolazine possesses antiarrhythmic activity, no randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial has specifically tested this hypothesis. Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials examining the efficacy of ranolazine against atrial and ventricular arrhythmias are warranted. One such clinical trial planned to start in the first half of 2011, is a study designed to determine the effect of ranolazine to reduce implantable cardiovascular-defibrillator shocks in high-risk patients for VT and VF. This is an NIH funded study sponsored by the University of Rochester: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01215253; Wojciech Zareba, Principal Investigator.

Recent trends in the management of patients with AF and cardiovascular co-morbidities (e.g. HF) indicate a shift from electrically-derived objectives, such as rate or rhythm control, to reductions in morbidity and mortality.64 The majority of patients with AF have a number of coexisting diseases such as hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery diseases, myocardial ischemia, diabetes, etc, which can be more serious than AF itself. These diseases often develop independently of AF, but may promote AF, and be aggravated by AF. Comprehensive treatment of AF and AF-associated diseases or consequences as well as co-existing morbidities would be preferable. In this respect, our recent experimental results showing synergistic electrophysiologic and anti-AF effects of the combination of ranolazine and dronedarone (described in D2) may be of particular interest. Dronedarone, a derivative of amiodarone, was approved by the FDA for the treatment of AF (for reduction of hospitalization). The anti-AF efficacy of dronedarone appears to be low,65, 66 clearly inferior to that of amiodarone,67 but its safety, as of this writing, appears to be superior to that of amiodarone.65, 67 During clinical development (e.g. ATHENA Trial), dronedarone was associated with a number of positive electrical and non-electrical effects in patients with AF, including reduction in hospitalizations, stroke, blood pressure, acute coronary syndrome, AF occurrence, and ventricular rate during AF.68, 69 Ranolazine, in addition to its antiarrhythmic actions, reduces ischemia.11, 56 Considering these non-electrical beneficial effects of dronedarone and ranolazine, their clinical safety profiles, and the synergistic anti-AF efficacy of their combination (demonstrated in experimental models43), the use of a fixed dose combination of these two drugs holds promise to not only be a safe and efficacious therapy for AF but may also prove to be clinically beneficial beyond suppression of AF.

Future research using new chemicals that are more potent, efficacious, specific (for NaChs) and selective (for late INa vs. peak INa) than ranolazine, are likely to further our understanding of the role of late INa in the genesis of AF and other cardiac arrhythmias.

Abbreviations

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- late INa

late sodium channel current

- IKr

rapidly activating delayed-rectifier potassium current

- peak INa

peak sodium channel current

- UDB

use-dependent block

- WT

wild type

- LA

local anesthetics

- hERG

ether-à-go-go-related gene

- AP

action potential

- APD

action potential duration

- IhERG

hERG K+ channel current

- LV

left ventricle

- ICa,L

L-Type calcium channel current

- AV

atrioventricular

- Ito

transient outward potassium current

- INCX

Na-Ca exchange current

- RMP

resting membrane potential

- IK1

inward rectifier K+ channel current

- Epi

epicardial

- PV

pulmonary vein

- HF

heart failure

- LVH

left ventricular hypertrophy

- TDR

transmural dispersion of repolarization

- ERP

effective refractory period

- PRR

post-repolarization refractoriness

- DTE

diastolic threshold of excitation

- CT

conduction time

- NaCh

sodium channel

- ITi

transient inward current

- DADs

delayed after depolarizations

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

- TdP

Torsade de Pointes

- LQTS

long QT syndrome

- RE

repetitive ventricular extrasystoles

- VF

ventricular fibrillation

- DFT

threshold for defibrillation

- Cai

intracellular calcium activity

- Nai

intracellular sodium activity

- AADs

antiarrhythmic drugs

- NSTE ACS

non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

- If

funny pacemaker current

- ICa-T

T-type calcium channel current

- IK-ATP

ATP-sensitive potassium channel current.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Antzelevitch received a research grant and serves as a consultant to Gilead Sciences and Dr. Belardinelli is employed by Gilead Sciences.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Zygmunt AC, et al. Electrophysiologic effects of ranolazine: a novel anti-anginal agent with antiarrhythmic properties. Circulation. 2004;110:904–10. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139333.83620.5D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song Y, Shryock JC, Wu L, et al. Antagonism by ranolazine of the pro-arrhythmic effects of increasing late INa in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44:192–9. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200408000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Undrovinas AI, Belardinelli L, Undrovinas NA, et al. Ranolazine improves abnormal repolarization and contraction in left ventricular myocytes of dogs with heart failure by inhibiting late sodium current. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:S161–S177. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Zygmunt AC, et al. Atrium-selective sodium channel block as a strategy for suppression of atrial fibrillation: differences in sodium channel inactivation between atria and ventricles and the role of ranolazine. Circulation. 2007;116:1449–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sossalla S, Kallmeyer B, Wagner S, et al. Altered Na+ currents in atrial fibrillation: effects of ranolazine on arrhythmias and contractility in human atrial myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2330–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zygmunt AC, Nesterenko VV, Rajamani S, et al. Mechanism of the preferential block of the atrial sodium current by ranolazine. Biophys J. 2009;96:250a. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fredj S, Sampson KJ, Liu H, et al. Molecular basis of ranolazine block of LQT-3 mutant sodium channels: evidence for site of action. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:16–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belardinelli L, Shryock JC, Fraser H. Inhibition of the late sodium current as a potential cardioprotective principle: effects of the late sodium current inhibitor ranolazine. Heart. 2006;92(Suppl 4):iv6–iv14. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.078790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajamani S, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Mechanism of ranolazine block of cardiac sodium channels. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2007;28:400. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajamani S, El-Bizri N, Shryock JC, et al. Use-dependent block of cardiac late Na+ current by ranolazine. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1625–31. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaitman BR. Ranolazine for the treatment of chronic angina and potential use in other cardiovascular conditions. Circulation. 2006;113:2462–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.597500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajamani S, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Rapid kinetic interactions of ranolazine with HERG K+ current. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;51:581–9. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181799690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davie C, Pierre-Valentin J, Pollard C, et al. Comparative pharmacology of guinea pig cardiac myocyte and cloned hERG IKr channel. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:1302–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.04099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilead Sciences I. Ranexa (Ranolazine) FDA Review Documents. NDA. 2003:21–256. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen TJ, Chapman RA. Effects of ranolazine on L-type calcium channel currents in guinea-pig single ventricular myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:249–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letienne R, Vie B, Puech A, et al. Evidence that ranolazine behaves as a weak beta1- and beta2-adrenoceptor antagonist in the cat cardiovascular system. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;363:464–71. doi: 10.1007/s002100000378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soliman D, Wang L, Hamming KSC, et al. Inhibition of reverse-mode sodium-calcium exchange by the anti-anginal agent ranolazine. FASEB J. 2010;24:961.1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sicouri S, Glass A, Belardinelli L, et al. Antiarrhythmic effects of ranolazine in canine pulmonary vein sleeve preparations. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1019–26. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Z, Fefelova N, Shanmugam M, et al. Angiotensin II induces afterdepolarizations via reactive oxygen species and calmodulin kinase II signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:128–36. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu L, Rajamani S, Li H, et al. Reduction of repolarization researve unmasks the pro-arrhythmic role of endogenous late sodium current in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1048–H1057. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00467.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antoons G, Oros A, Beekman JDM, et al. Late Na+ current inhibition by ranolazine reduces torsades de pointes in the chronic atrioventricular block dog model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:801–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spinelli W, Parsons RW, Colatsky TJ. Effects of WAY-123,398, a new class III antiarrhythmic agent, on cardiac refractoriness and ventricular fibrillation threshold in anesthetized dogs: a comparison with UK-68798, E-4031, and dl-sotalol. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;20:913–22. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Sicouri S, et al. Atrial-selective effects of chronic amiodarone in the management of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1735–42. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar K, Nearing BD, Carvas M, et al. Ranolazine exerts potent effects on atrial electrical properties and abbreviates atrial fibrillation duration in the intact porcine heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:796–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carvas M, Nascimento BC, Acar M, et al. Intrapericardial ranolazine prolongs atrial refractory period and markedly reduces atrial fibrillation inducibility in the intact porcine heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;55:286–91. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181d26416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. Atrial-selective sodium channel block for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2009;14:233–49. doi: 10.1517/14728210902997939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song Y, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. An increase of late sodium current induces delayed afterdepolarizations and sustained triggered activity in atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2031–H2039. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01357.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Undrovinas NA, Maltsev VA, Belardinelli L, et al. Late sodium current contributes to diastolic cell Ca2+ accumulation in chronic heart failure. J Physiol Sci. 2010;60:245–57. doi: 10.1007/s12576-010-0092-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasserstrom JA, Sharma R, O’Toole MJ, et al. Ranolazine Antagonizes the Effects of Increased Late Sodium Current on Intracellular Calcium Cycling in Rat Isolated Intact Heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:382–91. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu L, Shryock JC, Song Y, et al. Antiarrhythmic effects of ranolazine in a guinea pig in vitro model of long-QT syndrome. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:599–605. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu L, Shryock JC, Song Y, et al. An Increase in Late Sodium Current Potentiates the Proarrhythmic Activities of Low-risk QT-Prolonging Drugs in Female Rabbit Hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:718–26. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.094862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlsson L, Almgren O, Duker GD. Qtu-Prolongation and Torsades-de-Pointes Induced by Putative Class-III Antiarrhythmic Agents in the Rabbit - Etiology and Interventions. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1990;16:276–85. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199008000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang WQ, Robertson C, Dhalla AK, et al. Antitorsadogenic effects of (+/−)-N-(2,6-dimethyl-phenyl)-(4[2-hydroxy-3-(2-methoxyphenoxy)propyl]-1-piperazine (ranolazine) in anesthetized rabbits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:875–81. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindegger N, Hagen BM, Marks AR, et al. Diastolic transient inward current in long QT syndrome type 3 is caused by Ca2+ overload and inhibited by ranolazine. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:326–34. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Wu L, et al. Electrophysiologic properties and antiarrhythmic actions of a novel anti-anginal agent. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Therapeut. 2004;9 (Suppl 1):S65–S83. doi: 10.1177/107424840400900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antzelevitch C. Ranolazine: a new antiarrhythmic agent for patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes? Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:248–9. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, Vos MA. Assessing predictors of drug-induced torsade de pointes. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:619–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, Fraser H. Inhibition of late (sustained/persistent) sodium current: a potential drug target to reduce intracellular sodium-dependent calcium overload and its detrimental effects on cardiomyocyte function. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2004;6:i3–i7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar K, Nearing BD, Bartoli CR, et al. Effect of ranolazine on ventricular vulnerability and defibrillation threshold in the intact porcine heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:1073–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dhalla AK, Wang WQ, Dow J, et al. Ranolazine, an antianginal agent, markedly reduces ventricular arrhythmias induced by ischemia and iscehmia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1923–H1929. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00173.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morita N, Lee JH, Xie Y, et al. Suppression of re-entrant and multifocal ventricular fibrillation by the late sodium current blocker ranolazine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;52:366–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nieminen T, Nanbu DY, Datti IP, et al. Antifibrillatory effect of ranolazine during severe coronary stenosis in the intact porcine model. Heart Rhythm. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.11.029. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burashnikov A, Sicouri S, Di Diego JM, et al. Synergistic effect of the combination of dronedarone and ranolazine to suppress atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1216–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song Y, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. A slowly inactivating sodium current contributes to spontaneous diastolic depolarization of atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1254–H1262. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00444.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sicouri S, Burashnikov A, Belardinelli L, et al. Synergistic electrophysiologic and antiarrhythmic effects of the combination of ranolazine and chronic amiodarone in canine atria. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:88–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.886275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li D, Melnyk P, Feng J, et al. Effects of experimental heart failure on atrial cellular and ionic electrophysiology. Circulation. 2000;101:2631–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verheule S, Wilson E, Everett T, et al. Alterations in atrial electrophysiology and tissue structure in a canine model of chronic atrial dilatation due to mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2003;107:2615–22. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066915.15187.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roberts-Thomson KC, Stevenson I, Kistler PM, et al. The role of chronic atrial stretch and atrial fibrillation on posterior left atrial wall conduction. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1109–17. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirchhof P, Eckardt L, Franz MR, et al. Prolonged atrial action potential durations and polymorphic atrial tachyarrhythmias in patients with long QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:1027–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fabritz L, Damke D, Emmerich M, et al. Autonomic modulation and antiarrhythmic therapy in a model of long QT syndrome type 3. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:60–72. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blana A, Kaese S, Fortmuller L, et al. Knock-in gain-of-function sodium channel mutation prolongs atrial action potentials and alters atrial vulnerability. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1862–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antzelevitch C, Burashnikov A. Atrial-selective sodium channel block as a novel strategy for the management of atrial fibrillation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1188:78–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. Atrial-selective sodium channel blockers: do they exist? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;52:121–8. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31817618eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. New development in atrial antiarrhythmic drug therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:139–48. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koren MJ, Crager MR, Sweeney M. Long-term safety of a novel antianginal agent in patients with severe chronic stable angina: the Ranolazine Open Label Experience (ROLE) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1027–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson SR, Scirica BM, Braunwald E, et al. Efficacy of ranolazine in patients with chronic angina observations from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled MERLIN-TIMI (Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes) 36 Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1510–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Schwarz KQ, et al. Ranolazine shortens repolarization in patients with sustained inward sodium current due to type-3 long-QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:1289–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scirica BM, Morrow DA, Hod H, et al. Effect of ranolazine, an antianginal agent with novel electrophysiological properties, on the incidence of arrhythmias in patients with non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: results from the Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 36 (MERLIN-TIMI 36) randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2007;116:1647–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.724880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murdock DK, Overton N, Kersten M, et al. The effect of ranolazine on maintaining sinus rhythm in patients with resistant atrial fibrillation. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2008;8:175–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murdock DK, Kersten M, Kaliebe J, et al. The use of oral ranolazine to convert new or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a reveiw of experience with implications for possible “pill in the pocket” approach to atrial fibrillation. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2009;9:260–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murdock DK, Reiffel JA, Kaliebe JW, et al. The conversion of paroxysmal of initial onset of atrial fibrillation with oral ranolazine: implications for “pill in the pocket” approach in structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:A6.E58. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miles RH, Murdock DK. Ranolazine verses amiodarone for prophylaxis against atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass surgery. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:S258. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alboni P, Botto GL, Baldi N, et al. Outpatient treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation with the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2384–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prystowsky EN, Camm J, Lip GY, et al. The impact of new and emerging clinical data on treatment strategies for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:946–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Piccini JP, Hasselblad V, Peterson ED, et al. Comparative efficacy of dronedarone and amiodarone for the maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1089–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burashnikov A, Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C. Acute dronedarone is inferior to amiodarone in terminating and preventing atrial fibrillation in canine atria. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1273–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Le Heuzey JY, De Ferrari GM, Radzik D, et al. A short-term, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of dronedarone versus amiodarone in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: the DIONYSOS study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:597–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hohnloser SH, Crijns HJ, van EM, et al. Effect of dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:668–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Connolly SJ, Crijns HJ, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. Analysis of stroke in ATHENA: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-arm trial to assess the efficacy of dronedarone 400 mg BID for the prevention of cardiovascular hospitalization or death from any cause in patients with atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter. Circulation. 2009;120:1174–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.875252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Song Y, Shryock J, Wagner S, et al. Blocking late sodium current reduces hydrogen peroxide-induced arrhythmogenic activity and contractile dysfunction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:214–22. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wagner S, Ruff HM, Weber SL, et al. Reactive Oxygen Species-Activated Ca/Calmodulin Kinase II{delta} Is Required for Late INa Augmentation Leading to Cellular Na and Ca Overload. Circ Res. 2011 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221911. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L. The role of sodium channel current in modulating transmural dispersion of repolarization and arrhythmogenesis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17(Suppl 1):S79–S85. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu L, Guo D, Li H, et al. Role of late sodium current in modulating the proarrhythmic and antiarrhythmic effects of quinidine. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1726–34. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu L, Rajamani S, Shryock JC, et al. Augmentation of late sodium current unmasks the proarrhythmic effects of amiodarone. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:481–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jia S, Lian J, Guo D, et al. Modulation of the late sodium current by the toxin, ATX-II, and ranolazine affects the reverse use-dependence and proarrhythmic liability of I(Kr) blockade. Br J Pharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu J, Cheng L, Lammers WJ, et al. Sinus node dysfunction in ATX-II-induced in-vitro murine model of long QT3 syndrome and rescue effect of ranolazine. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;98:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sicouri S, Timothy KW, Zygmunt AC, et al. Cellular basis for the electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestations of Timothy syndrome: effects of ranolazine. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:638–47. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hoyer K, Song Y, Wang D, et al. Reducing the late sodium current improves cardiac fuction during sodium pump inhibition by ouabain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011 doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.176776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ma J, Wu L, Li H, et al. Increased CO2 levels augment late sodium current and cause Torsade de Pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(Suppl A):A102. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I, et al. Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature09747. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aiba T, Hashambhoy YL, Barth AS, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy augments myofilament Ca2+ responsiveness in failing myocardium via altered phosphorylation. Circulation. 2009;120:S627. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Murdock DK, Kaliebe J, Overton N. Ranolozine-induced suppression of ventricular tachycardia in a patient with nonischemic cardiomyopathy: a case report. PACE. 2008;31:765–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scirica BM, Braunwald E, Belardinelli L, et al. Relationship between nonsustained ventricular tachycardia after non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome and sudden cardiac death: observations from the metabolic efficiency with ranolazine for less ischemia in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 36 (MERLIN-TIMI 36) randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2010;122:455–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.937136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nanda S, Martinez MW, Dey T. Ranolazine is effective for acute or chronic ischemic dysfunction with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:822. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lemoine MD, Gi XY, Chartier D, et al. Electrophysiological basis for atrial arrhyhtmia in Long QT syndrome mouse model. Circulation. 2010;122:A11401. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Antzelevitch C, Burashnikov A. Atrial-selective sodium channel block as a novel strategy for the management of atrial fibrillation. J Electrocardiol. 2009;42:543–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]