Abstract

The environmental bacterium Burkholderia cenocepacia causes opportunistic lung infections in immunocompromised individuals, particularly in patients with cystic fibrosis. Infections in these patients are associated with exacerbated inflammation leading to rapid decay of lung function and in some cases resulting in cepacia syndrome, which is characterized by a fatal acute necrotizing pneumonia and sepsis. B. cenocepacia can survive intracellularly in macrophages by altering the maturation of the phagosome, but very little is known on macrophage responses to the intracellular infection. Here, we have examined the role of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in B. cenocepacia-infected monocytes and macrophages. We show that PI3K/Akt activity was required for NF-κB activity and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines during infection with B. cenocepacia. In contrast to previous observations in epithelial cells infected with other Gram-negative bacteria, Akt did not enhance IKK or NF-κB p65 phosphorylation but rather inhibited GSK3β, a negative regulator of NF-κB transcriptional activity. This novel mechanism of modulation of NF-κB activity may provide a unique therapeutic target for controlling excessive inflammation upon B. cenocepacia infection.

Introduction

Bukholderia cenocepacia is one of the members of the Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc). This is a Gram-negative opportunistic respiratory pathogen that represents a threat to immunocompromised individuals, especially patients with cystic fibrosis (1–3). What is particularly troublesome is that these bacteria are also highly resistant to many antibiotics, making treatment difficult (4,5). Because of this, it is critical to gain an understanding of host immune responses to this organism, as this may provide alternative means to overcoming the current limitations for treatment.

One major contributing factor to the morbidity and mortality caused by B. cenocepacia infection is an exacerbated inflammatory response, which causes collateral tissue damage (6,7). Accordingly, administration of anti-inflammatory corticosteroids has been associated with favorable patient outcome during B. cepacia infection (8). It has also been demonstrated in vivo that TLR/MyD88 driven inflammation is detrimental to the host, as MyD88−/− mice show a survival advantage over wild-type mice after challenge with B. cencoepacia (9). Indeed, TLR5 plays a key role in promoting exacerbated inflammation in susceptible individuals (10,11).

One of the key downstream effects of TLR/MyD88 pathway activation is TNFα production. This cytokine has been shown to be a major mediator of mortality in an in vivo mouse model of B. cenocepacia infection, as TNFα−/− mice were protected against a challenge lethal to wild-type mice (9). Hence, an understanding of how infection leads to TNFα production may lead to newer, more effective treatments designed to regulate TNFα production and other deleterious pro-inflammatory responses.

Numerous studies have highlighted the importance of macrophages during B. cenocepacia infection, as they are a site of bacterial replication much like lung epithelial cells (12,13). It is interesting to note that CFTR-defective or CFTR-inhibitor-treated wild-type murine macrophages show delayed phagolysosomal fusion compared to control (14). This helps to explain the persistence of B. cenocepacia in individuals with cystic fibrosis, as their macrophages would be less able to control the bacteria. Monocytes/macrophages are also major producers of inflammatory mediators such as TNFα and IL-8 (7,15–17), which contribute to the hyperinflammatory state following B. cenocepacia infection.

PI3K/Akt signaling is known to regulate various biological functions, including the pro-inflammatory response to TLR signaling. However, its effect on inflammatory response differs, depending upon several factors that remain to be fully understood (18). Here, we have investigated the role of PI3K/Akt signaling on IKK/NF-κB activation and the ensuing pro-inflammatory response from mononuclear phagocytes infected with B. cenocepacia. We demonstrate that PI3K and Akt promote NF-κB activity and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, but not through IKK nor NF-κB p65 phosphorylation. Instead, PI3K/Akt serves to inactivate GSK3β, a downstream repressor of NF-κB. These findings suggest that targeting PI3K/Akt/GSK3β signaling may be of therapeutic value within the context of B. cenocepacia infection.

Materials and Methods

Cells and reagents

RAW 264.7 cells obtained from ATCC were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT), L-glutamine, penicillin (10,000 U/ml) and streptomycin (10,000 μg/ml) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The BAY 11-7085 (5μM) IKK inhibitor was a generous gift from Dr. Denis Guttridge (The Ohio State University). LY294002 (20μM) PI3K inhibitor was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). SB-216763 (2μM) GSK3β inhibitor was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). DMSO vehicle control (0.2%) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Akt Inhibitor X (10μM) was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA) and dissolved in water. Antibodies against phospho-Akt-serine-473, phospho-IKKα-serine-180/β-serine-181, phospho-NF-κBp65-serine-536, phospho-GSK3α-serine-21/β-serine-9, phospho-GSK3β-serine-9, and GSK3β were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, Massachusetts). Antibodies against Akt and actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Bone marrow-derived macrophages

Wild-type and MyrAkt expressing mice were sacrificed according to institution-approved animal care and use protocols. Bone marrow cells were collected and differentiated as previously described with MCSF (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) and polymyxin-B (CalBiochem, San Diego, CA) (19–21).

Peripheral blood monocyte isolation

Human peripheral blood monocytes (PBM) were isolated by centrifugation through a Ficoll gradient followed by CD14-positive selection by Magnet-Assisted Cell Sorting (MACS, Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) according to manufacturer instructions as previously described (22).

Bacterial infections

All monocyte/macrophage infections were conducted in 5% or 10% heat-inactivated FBS-containing RPMI-1640 without antibiotic. Burkholderia cenocepacia K56-2 isolate was grown in L.B. broth (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 12–14 hours to post-logarithmic phase. Optical density at 600 nm was taken to assess the density of cultures and calculate the multiplicities of infection. Serial dilutions of cultures and plating on L.B. agar to count colony forming units was done to verify accuracy of the MOI calculations. Prior to infection, cultures were centrifuged, washed, and resuspended in macrophage culture media.

ELISA cytokine measurements

Cell-free supernatants were assayed by sandwich ELISA. Human TNFα, mouse TNFα, mouse IL-6, and mouse RANTES ELISA kits were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and human IL-6 and human IL-8 ELISA kits were obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). The manufacture’s instructions were followed as previously described (19,20).

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in TN1 buffer (50mM Tris [pH 8.0], 10 nm EDTA, 10M Na4P2O7, 10 nM NaF, 1% Triton-X 100, 125nM NaCl, 10nM Na3VO4, 10 μg/ml of both aprotinin and leupeptin. Whole cell lysates were electrophoretically separated on 10% acrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and then probed with antibody of interest. Detections were performed using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies followed by development with enhanced chemiluminescence western blotting substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) as previously described (19,20).

CFU assays

Assays using the aminoglycoside-sensitive strain of K56-2 were conducted as done by Hamad et al. (13). Primary macrophages were infected with B. cenocepacia then placed on a rocker at room temperature for 5 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 400 × g for 4 min. After 1 hour of infection the media was removed and cells washed with PBS. Media containing 50μg/ml of gentamicin was added for 30 minutes. We found that under these conditions >98% of the aminoglycoside sensitive K56-2 strain was killed, though less than 12% of the parental K56-2 strain was killed under the same conditions. After treatment, cells were again washed in PBS to remove antibiotic, then either lysed in 0.1% Triton-X (1-hour infection time) or resuspended in culture media for later lysis at 8- and 24-hour time points. Lysed samples were immediately serially diluted ten-fold and plated on L.B. agar plates. At 24–36 hour post-plating, CFUs were counted. The dual-antibiotic CFU assays were conducted as above, with the exception that parental strain K56-2 was used and extracellular bacteria were killed with gentamicin (500μg/ml) plus ceftazidime (250μg/ml) for one hour (12,23). We found that this killed >98% of K56-2 B. cenocepacia.

Luciferase assays

Transfected macrophages were uninfected or were infected for 5 hours (time of robust NF-κB-luciferase activity, Supplemental Fig. 1) with B. cenocepacia. At the end of the infection period cells were washed with PBS and then lysed in 200 μl of Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin). Luciferase activity was then measured using Luciferase Assay Reagent (Promega), as previously described (20). Data are expressed as percent increase over matched uninfected control samples.

Transfection

5 μg of pcDNA vector with or without wild-type human GSK3β, Addgene plasmid 14753 (24), (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) was used for each transfection with 10×106 RAW 264.7 cells. Amaxa solution V was used for electroporation using program U-14 as previously described (20). Infections were performed 14 hours post-transfection. Overexpression was confirmed by western blotting of GSK3β. For NF-κB activity assays 2 μg of NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid was transfected into RAW 264.7 cells as described above. Transfection efficiency is routinely tested by Flow cytometry analysis of EGFP-transfected cells. We are able to achieve up to 80% transfection efficiency in Raw 264.7 cells with minimal effect on cell viability.

Results

PI3K signaling is required for the pro-inflammatory response to B. cenocepacia

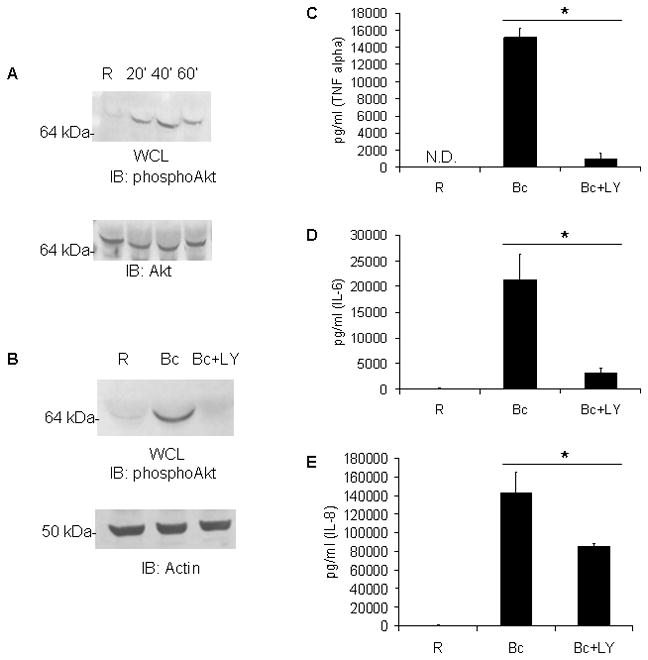

PI3K signaling leads to generation of phosphatidylinositol-(3,4)-bisphosphate and phosphatidylinositol-(3,4,5)-trisphosphate, which result in phosphorylation and activation Akt at the plasma membrane. This drives numerous cellular process, including the production and release of pro-inflammatory mediators (18,25). Here we examined PI3K/Akt signaling in primary human monocytes infected with B. cenocepacia. Peripheral blood monocytes (PBM) were isolated and infected with B. cenocepacia at an MOI of 5 for time points of 20, 40 or 60 minutes. Whole cell lysates were then probed for phospho-Akt levels by western blotting followed by re-probing for total Akt. It is apparent that Akt is robustly activated within 20 minutes of infection and is sustained through the first hour (Figure 1A). We also tested the ability of killed B. cenocepacia to activate Akt and found that both live and dead bacteria induced this response within one hour (data not shown). Therefore, this signaling event is not dependent upon bacterial viability.

Figure 1. The PI3K/Akt pathway is activated by B. cenocepacia and PI3K is required for inflammatory cytokine production.

A Primary human peripheral blood monocytes (PBM) were infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 20, 40, or 60 minutes. ‘R’ represents resting or uninfected samples. Western blots on cell lysates were done to measure pSer473-Akt, followed by reprobes for total Akt as a loading control. B PBM were pre-treated with DMSO vehicle control or the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (20μM) for 30 minutes, then infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 8 hours. To ensure inhibitor effectiveness, cells were lysed and pSer473-Akt measured by western blotting, with actin reprobe as loading control. C–E Pro-inflammatory cytokine production of PBM from Figure 1B was measured by performing sandwich ELISAs on cell-free supernatants for C TNFα, D IL-6, or E IL-8. 3 independent experiments were done. * denotes a p value < 0.05 from Student’s t-test.

To then investigate the function of PI3K on host-inflammatory response PBM were pretreated with vehicle control or the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (26) and infected with B. cencoepacia at an MOI of 5 for 8 hours. The effectiveness of the inhibitor under these conditions was verified by western-blotting of phospho-Akt. PBM pretreated with vehicle showed high levels of Akt activation upon infection, while PBM given the PI3K inhibitor and infected did not (Figure 1B).

Next we examined the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the presence or absence of the PI3K inhibitor in PBM infected with B. cenocepacia. Matched supernatant from the samples in Figure 1B was collected and pro-inflammatory cytokine production assayed by ELISA. Infected PBM showed strong induction of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 compared to uninfected cells. However, PBM pretreated with LY294002 produced significantly less after infection (Figures 1C, 1D, and 1E). Similar results were obtained with bone marrow-derived murine macrophages (data not shown). Therefore, the inflammatory response to B. cenocepacia by monocytes/macrophages requires PI3K signaling.

Akt promotes the pro-inflammatory response to B. cenocepacia

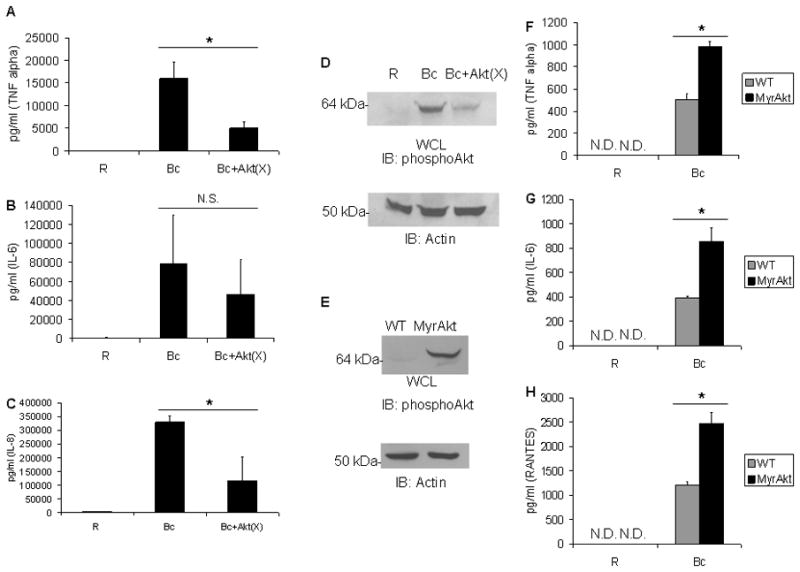

Given that class I PI3K activate Akt (25) and we find that PI3K is required for the monocyte/macrophage pro-inflammatory response to B. cenocepacia, we next examined whether Akt activation could be linked to the pro-inflammatory response in infected PBMs. Therefore, PBM were pre-treated with the Akt inhibitor Akt(X) (27) or vehicle control and infected with B. cenocepacia for 8 hours. Inhibition of Akt led to reduced production of TNFα, IL-6 and IL-8 compared to cells pretreated with vehicle control (Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C). The reduction in IL-6 did not reach statistical significance, however, and this may be due to residual Akt activation even in the presence of Akt(X) following infection (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Akt promotes the pro-inflammatory cytokine production elicited by B. cenocepacia.

A–C PBM were pre-treated with H2O vehicle control or the Akt inhibitor Akt(X) (10μM) for 30 minutes, and then infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 8 hours. Sandwich ELISAs were done to measure ATNFα, BIL-6, or CIL-8 in cell-free supernatants. 3 independent experiments were done. * denotes a p value < 0.05 by Student’s t-test. D Matched PBM samples run in parallel to that of figure 2A were lysed and pSer-Akt measured by western blotting, followed by reprobe for actin as a loading control. E Bone marrow-derived macrophages from wild-type mice and transgenic mice expressing a macrophage-specific myristoylated Akt were lysed and pSer-Akt measured by western blotting. F–H Bone marrow-derived macrophages from wild-type or MyrAkt-expressing mice were infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 8 hours. Sandwich ELISAs were done to measure FTNFα, GIL-6, and HRANTES. This represents a triplicate of biological samples and * denotes a p value < 0.05 from Student’s t-test.

The above findings suggest that Akt activation is required for cytokine production following B. cenocepacia infection. To test whether Akt could drive production of these cytokines, we infected bone marrow-derived macrophages from wild-type mice or from mice expressing a macrophage-specific myristoylated Akt (MyrAkt) (28). We verified the constitutive activation of Akt in unstimulated macrophages by phospho-Akt western blot (Figure 2E). Following 8-hour infection of wild-type and MyrAkt macrophages with B. cenocepacia, we performed ELISAs and found significantly enhanced production of TNFα, IL-6 and RANTES in the MyrAkt expressing cells (Figure 2F, 2G and 2H).

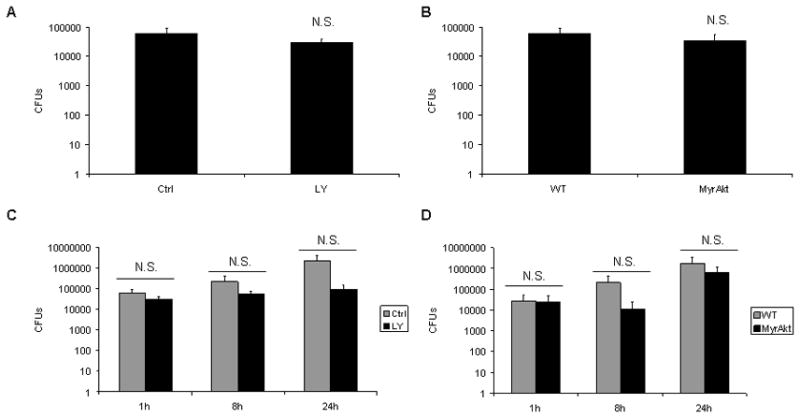

PI3K/Akt do not regulate uptake nor intramacrophage replication of B. cenocepacia

PI3K signaling has been reported to influence both phagocytosis (29,30) and intra-macrophage survival (21) of other Gram-negative bacteria. To evaluate its role in macrophages infected with B. cenocepacia, we investigated bacterial uptake and replication in PBM after inhibition of PI3K. To overcome the natural antibiotic resistance of B. cenocepacia and to facilitate these experiments we used an aminoglycoside-sensitive strain of B. cenocepacia (strain MH1K) that can be killed with a low concentration of gentamicin but does not differ with the parental isolate in terms of intracellular survival and phagosomal trafficking (13). We pretreated primary murine macrophages with LY294002 and infected with B. cenocepacia MH1K. In parallel, we also infected MyrAkt-expressing macrophages. Colony-forming-units were determined at 1 hour of infection to estimate bacterial uptake (Figure 3A and 3B) and at 8 and 24 hours post-infection to estimate intracellular replication (Figures 3C and 3D). We found no influence of PI3K/Akt activity on internalization or bacterial replication. We also performed these experiments with the parental B. cenocepacia strain plus the dual antibiotic treatment of gentamicin (500μg/ml) and ceftazidime (250μg/ml) as done by Sajjan et al. (12), and the results also indicated no effect of PI3K/Akt on phagocytosis or intracellular replication of B. cenocepacia in mononuclear phagocytes (data not shown). These findings suggest that PI3K/Akt can be targeted to limit inflammation without altering the intra-macrophage lifecycle of B. cenocepacia.

Figure 3. PI3K/Akt does not regulate phagocytosis or intracellular replication of B. cenocepacia within macropahges.

A 4×105 BMM were pretreated with DMSO or LY294002 for 30 minutes and then infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 1 hour. At the end of the infection period washed treated with gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria for 30 minutes. Cells were washed, lysed, serially diluted, and plated on L.B. agar. Graphs represent the average and standard deviation of recovered CFUs for 3 independently infected samples. A student’s t test was done to determine significance. N.S. designates non-significant, p value >0.05 B Wild-type or MyrAkt BMM were infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 1 hour as done in figure 3A. C 4×105 BMM were pretreated with DMSO or LY294002 for 30 minutes and then infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 1 hour. Samples were lysed at 1 hour or cultured in fresh macrophage culture medium for 8 or 24 hours, then lysed. Graphs represent the average and standard deviation of recovered CFUs for 3 independently infected samples. A student’s t test was done to determine significance. N.S. designates non-significant, p value >0.05 D 4×105 wild-type or MyrAkt BMMs were infected and treated as in Figure 3C.

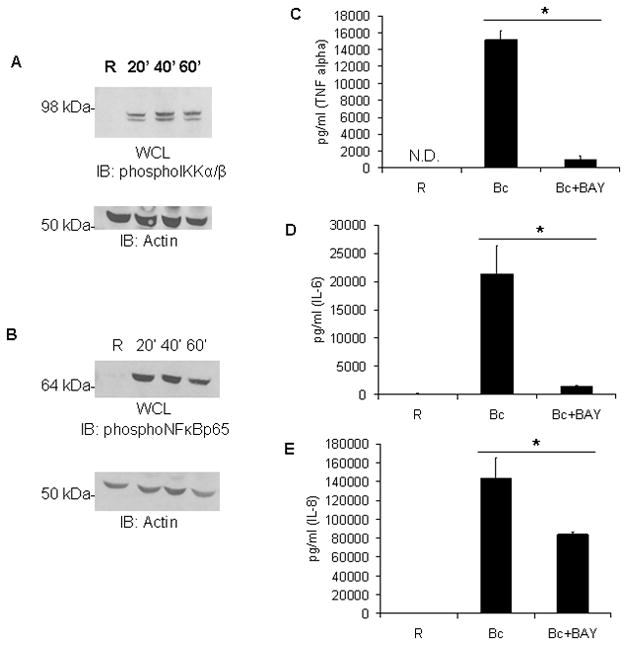

IKK/NF-κB are activated by B. cenocepacia and required for inflammatory responses

We have shown that PI3K/Akt promotes inflammatory responses to B. cenocepacia without influencing uptake or replication in macrophages. Next, to understand how PI3K and Akt promote this inflammatory response we examined activation of the IKK/NF-κB pathway. NF-κB drives production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and has been shown to be responsive to PI3K/Akt signaling (20). We infected PBM with B. cenocepacia for 20, 40 and 60 minutes, and measured IKK phosphorylation by western blotting. Results show that there was phosphorylation of IKKα and β within the first 20 minutes of infection (Figure 4A). Phosphorylation of the IKK complex triggers a number of events that lead to NF-κB nuclear translocation and gene transcription (31). The NF-κBp65 subunit itself can also be phosphorylated, which enhances its transcriptional activity (32). We examined the status of serine-536 phosphorylation on NF-κBp65 and found that it was also rapidly phosphorylated in response to B. cenocepacia infection (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. The IKK/NF-κB pathway is activated by B. cenocepacia and is required for pro-inflammatory cytokine production.

A PBM were infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 20, 40, or 60 minutes. ‘R’ represents resting or uninfected samples. Cells were lysed and proteins analyzed by western blotting for phospho-IKKα/β, followed by anti-Actin as a loading control. B pSer536 of NF-κB p65 was measured in matched samples from Figure 3A by western blotting and reprobed with anti-Actin as a loading control. C–E PBM were pretreated with DMSO vehicle control or an IKK/NF-κB inhibitor, BAY7085 (5μM), for 30 minutes and then infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 8 hours. Sandwich ELISAs were done to measure levels of C TNFα, D IL-6, or E IL-8 in cell-free media samples. Graphs represent 3 biological samples and * denotes a p value < 0.05 from Student’s t-test.

To test the requirement of NF-κB for mediating pro-inflammatory responses to B. cenocepacia we pre-treated PBM with an IKK inhibitor, BAY 11-7085 (33), before infection. In the presence of this inhibitor, B. cenocepacia-driven production of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 was greatly diminished compared to control following infection (Figures 4C, 4D, 4E). These results indicate that IKK signaling to NF-κB is a major mediator of pro-inflammatory responses to B. cenocepacia. In light of our finding that PI3K/Akt promoted cytokine production after infection, the possibility arose that PI3K/Akt drove IKK/NF-κB activation.

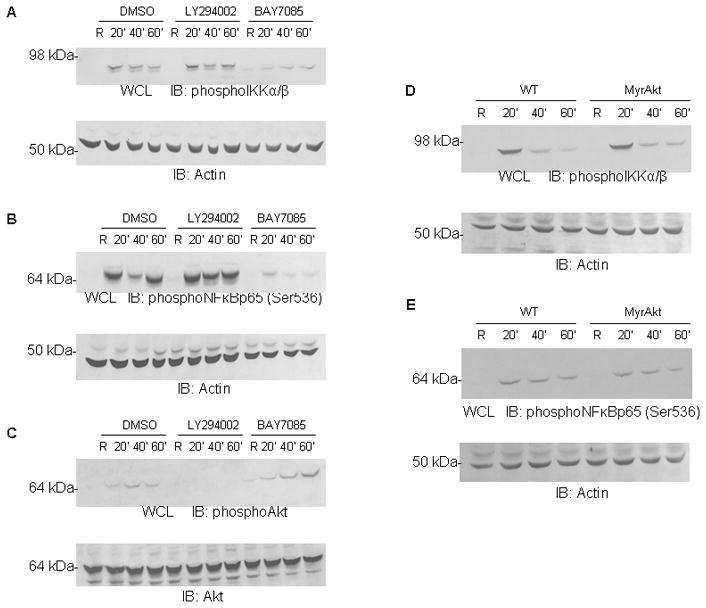

Activation of IKK/NF-κB and PI3K/Akt are independent of each other

Our data indicate that both PI3K/Akt and IKK/NF-κB are required for the monocyte/macrophage inflammatory response to B. cenocepacia. To determine whether the two pathways were linked, we examined their activation in the presence or absence of specific inhibitors. PBM were pretreated with vehicle control, PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) or IKK inhibitor (BAY 11-7085), then infected with B. cenocepacia for the indicated time points. Surprisingly, the PI3K inhibitor did not impair IKKα/β phosphorylation (Figure 5A) nor NF-κBp65-Ser536 phosphorylation (Figure 5B) despite blocking Akt phosphorylation. Conversely, the IKK inhibitor blocked IKKα/β and NF-κBp65-Ser536 phosphorylation but not Akt phosphorylation (Figure 5C). These results show that each pathway is activated independently of the other following B. cenocepacia infection.

Figure 5. PI3K/Akt do not influence IKK/NF-κB phosphorylation.

A–C PBM were pretreated with DMSO vehicle control LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor) or BAY 11-7085 (IKK/NF-κB inhibitor) for 30 minutes and then infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 20, 40, or 60 minutes. ‘R’ represents resting or uninfected samples. Cells were lysed and western blotting done to measure Aphospho-IKKα/β, Bphospho-NF-κBp65 (Ser536), and Cphosphor-serine Akt. Actin and total Akt were probed as loading controls. D–E Bone marrow-derived macrophages from wild-type or myrAkt-expressing mice were infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 20, 40, or 60 minutes. ‘R’ represents resting or uninfected samples. Cells were lysed and western blotting done to measure Dphospho-IKKα/β and Ephospho-NF-κBp65 (Ser536). Actin and was used a loading control.

Because our earlier results (Figure 2) showed that MyrAkt-expressing macrophages produced more pro-inflammatory cytokines than wild-type upon infection, we also examined IKK/NF-κB phosphorylation in the MyrAkt-expressing macrophages. Wild-type and MyrAkt macrophages were infected with B. cenocepacia for the indicated time points. Consistent with results in Figure 1A, Akt activation did not enhance phosphorylation of IKK nor NF-κB (Figures 5D and 5E). We have shown that PI3K/Akt are required for cytokine production (Figures 1 and 2), but these results suggest that either PI3K/Akt signaling is required in parallel to NF-κB for cytokine production, or alternatively that any effect of PI3K/Akt on NF-κB would be downstream of NF-κB activation itself.

To directly test whether PI3K/Akt influenced NF-κB-driven gene transcription, we transiently transfected RAW 264.7 cells with the NF-κB luciferase reporter and pretreated with PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) or IKK inhibitor (BAY 11-7085). Cells were then infected and NF-κB activity measured by luciferase assay. NF-κB activity markedly increased upon infection, and as expected the IKK inhibitor (BAY 11-7085) blocked this response. Strikingly, the PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) also strongly impaired NF-κB activity (Figure 6A). These results confirm that PI3K signaling is required for NF-κB-driven gene trasncription following B. cenocepacia infection. Hence, we concluded from all of the results that in infected mononuclear phagocytes, PI3K influences NF-κB activity, but does so downstream of IKK.

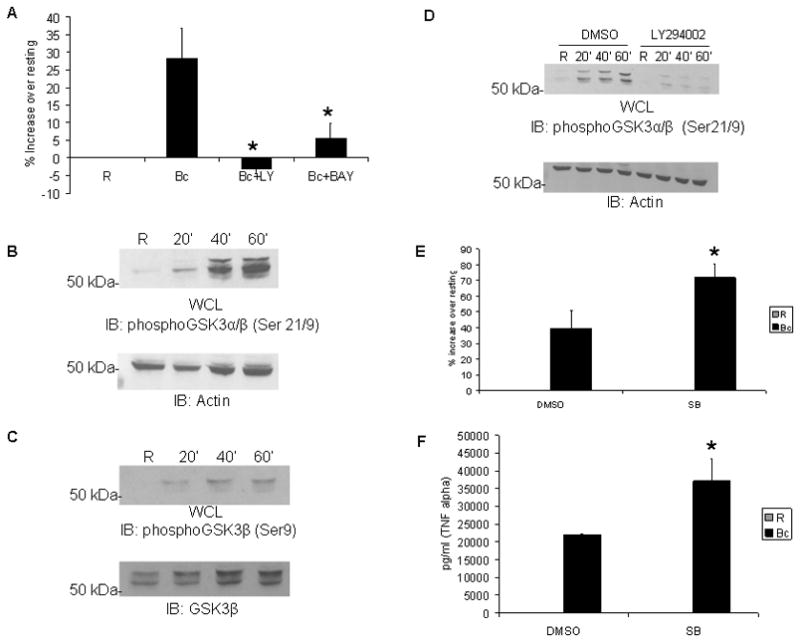

Figure 6. The PI3K/Akt pathway regulates NF-κB activity through GSK3β.

A RAW264.7 cells were transfected with an NF-κB luciferase reporter. 14 hours post-transfection these cells were infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 5 hours, the infection time yielding robust NF-κB-luciferase activity (Supplemental Fig. 1). Luciferase activity was measured by a luminometer and values converted into percent increase over matched resting/uninfected samples. B PBM were infected with B. cenocepacia for 20, 40, or 60 minutes. ‘R’ represents uninfected cells. Western blotting was done on cell lysates to measure phospho-GSK3α/β, then reprobed with anti-actin as a loading control. C Matched cell lysates from Figure 5B were tested by western blotting for phospho-GSK3β, then reprobed for total GSK3β as a loading control. D PBM were treated with DMSO vehicle control or the LY294002 for 30 minutes, and then infected with B. cenocepacia for 20, 40, or 60 minutes. ‘R’ represents uninfected cells. Western blots were done on cell lysates for phospho-GSK3α/β, followed by reprobing for actin as a loading control. E RAW264.7 cells were transfected with an NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid. Transfected cells were pretreated with DMSO vehicle control or SB-216763 GSK3β inhibitor for 30 minutes, then infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 5 hours. Cells were lysed and luciferase activity measured by a luminometer. Data are expressed as percent increase in activity over matched uninfected control. F RAW 264.7 cells were pre-treated with DMSO vehicle control or SB-216763, and then infected with B. cenocepacia (B.c.) at an MOI of 5 for 8 hours. Cleared cell lysates were assayed for TNFα production by ELISA. Data represent the average of 3 samples and error bars denote standard deviation. * denotes a p value < 0.05 from Student’s t-test.

PI3K/Akt regulates NF-κB activity through GSK3β

One strong candidate downstream target of Akt is GSK3β. This molecule has been reported to both promote (34) and repress (35–37) NF-κB activity. This molecule is normally active until phosphorylation occurs on serine-21 of GSK3α (38) or serine-9 of GSK3β (39). We infected PBM with B. cenocepacia and examined both GSK3α and GSK3β phosphorylation by western blotting. As shown in Figure 6B, infection induces strong phosphorylation of GSK3α/β at Serine 21 and 9. Specific examination of Serine 9 on GSK3β confirmed its phosphorylation following infection (Figure 6C).

It is reported that Akt controls this inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK3β (40), so we tested whether PI3K activity during B. cenocepacia infection was required for GSK3α/β phosphorylation. PBM were pretreated with either the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or vehicle control, followed by infection. Western blotting shows rapid phosphorylation of GSK3α/β with vehicle control. However, PI3K inhibition strongly attenuated this infection-mediated phosphorylation (Figure 6D). This suggests that inhibition of GSK3β following B. cenocepacia infection is PI3K-dependent. To determine whether GSK3β modulated phosphorylation of NF-κB, PBM were pretreated with either DMSO or the GSK3β inhibitor SB-21673 (41), then infected for 20, 40 or 60 minutes. Western blots showed that inhibition of GSK3β did not lead to increases in NF-κB phosphorylation (Supplemental Fig. 2). This suggests that any effect of GSK3β would be at the functional level, downstream of NF-κB phosphorylation.

To test this, we examined the effect of GSK3β on NF-κB and inflammatory response during B. cenocepacia infection, using the NF-κB luciferase reporter as in Figure 6A. Reporter-transfected cells were treated with vehicle control or with the GSK3β-specific inhibitor SB-216763. Following this, cells were infected with B. cenocepacia for 5 hours. Results showed that inhibition of GSK3β led to increased NF-κB reporter activity compared to vehicle control (Figure 6E). Inhibitor treatment alone led to a modest yet measurable increase in basal NF-κB activity (Supplementary Fig. 3), which also supports the findings (35–37) that GSK3β can repress NF-κB activity. Collectively, these results suggest that, within the context of B. cenocepacia-infected macrophages, GSK3β represses NF-κB activity but not NF-κB phosphorylation. This is also in agreement with the findings that both PI3K and Akt promote NF-κB activity, because these signaling molecules inactivate GSK3β. To test the functional outcome of this, we collected supernatants from infected macrophages and measured TNFα production by ELISA. Results showed a significant increase in TNFα with the GSK3β inhibitor (Figure 6F).

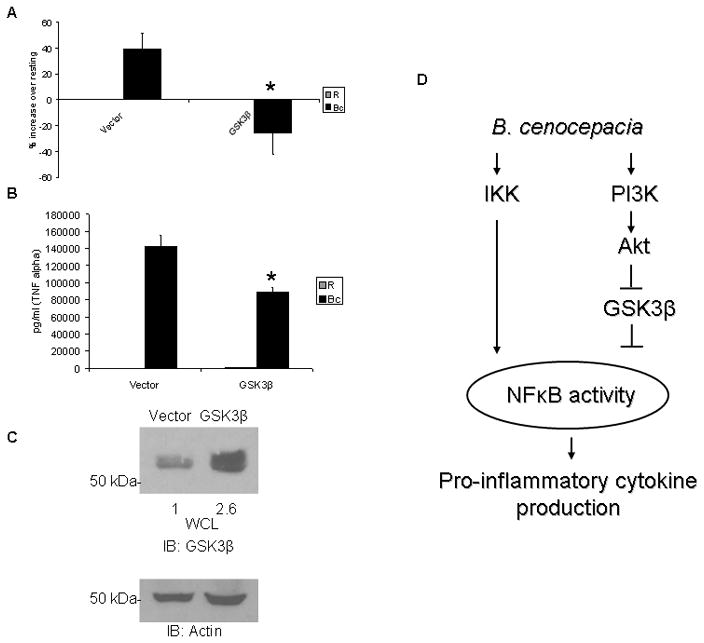

Overexpression of GSK3β represses NF-κB and the pro-inflammatory response

To confirm the function of GSK3β as a repressor of NF-κB and inflammatory response to B. cenocepacia, we co-transfected RAW264.7 macrophages with an NF-κB luciferase reporter and either vector control or wild-type GSK3β (24). Macrophages overexpressing GSK3β showed reduced NF-κB activity compared to vector control in response to B. cenocepacia infection (Figure 7A). Consistent with our earlier results showing that GSK3β represses NF-κB activity in infected macrophages, GSK3β overexpression decreased basal NF-κB activity by 50%. We also found reduced production of TNFα in overexpressing macrophages (Figure 7B). Verification of GSK3β over-expression was done by Western blotting (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. GSK3β overexpression inhibits B. cenocepacia-induced NF-κB activation and inflammatory response.

A RAW264.7 macrophages were transfected with an NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid and either vector control or wild-type GSK3β plasmid. 14 hours post-transfection, macrophages were infected with B. cenocepacia at an MOI of 5 for 5 hours. Cells were lysed and luciferase activity measured by a luminometer. Data are expressed as percent increase over matched uninfected control. B RAW264.7 macrophages were transfected with vector control or wild-type GSK3β plasmid. 14 hours post-transfection the macrophages were infected with B. cenocepacia at an MOI of 5 for 24 hours. Cleared cell lysates were collected and assayed for TNFα production by ELISA. Data represent the average of 3 samples and error bars denote standard deviation. * denotes a p value < 0.05 from Student’s t-test. C Western blots to measure GSK3β were done with cell lysates from uninfected macrophages transfected with either vector or GSK3β plasmid, followed by reprobes for actin as loading control. Densitometry quantification of GSK3β is over-expression is shown and normalized by Actin. D Model of interactions between IKK, PI3K/Akt, and GSK3β pathways for regulating NF-κB and inflammatory response to B. cenocepacia.

In summary, our results show that PI3K/Akt and NF-κB activation are required for pro-inflammatory responses to B. ceoncepacia. However, rather than driving NF-κB activation through IKK phosphorylation, PI3K/Akt signaling serves to inactivate the inhibitory GSK3β.

Discussion

We have found that PI3K/Akt signaling inactivates GSK3β to permit enhanced NF-κB activity and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines following B. cenocepacia infection. Akt has been shown to regulate NF-κB activity through its influence on IKK (42). Akt can directly phosphorylate IKKα to mediate NF-κB nuclear translocation and gene transcription (43) depending on the ratio of IKKα to IKKβ within the cell (44). PI3K can also lead to phosphorylation and activation of NF-κBp65 through Akt, independently of IκB degradation (45). Within the context of B. cenocepacia infection, however, it appears that the inactivation of GSK3β is the major mechanism by which PI3K/Akt modulated NF-κB activity. Of note, the PI3K pathway did not regulate expression of other negative regulators such as IRAK-M (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Studies of inflammatory responses to Gram-negative bacteria in intestinal epithelial cells showed that PI3K/Akt inhibition resulted in decreased NF-κBp65 phosphorylation (46,47), which we did not observe. Both the species of bacteria and the type of host cell (epithelial cells versus monocytes/macrophages) may be responsible for these disparities. Inhibition of PI3K/Akt in vivo using gp91phox−/− mice (48) or vinblastine-immunosuppressed mice (9) may be required to determine the in vivo consequences of manipulating PI3K/Akt/GSK3β on bacterial growth, cytokine production, and overall host-resistance to infection.

Our results are in agreement with Hii et al., who found PI3K to be critical for pro-inflammatory responses of HEK293T cells infected with Burkholderia pseudomallei (49). However, it remains to be tested whether the mechanism of GSK3β inhibition by PI3K/Akt is also similar, as the nature of B. cenocepacia versus B. pseudomallei infection is quite different (50). Indeed, there is tight regulation of PI3K/Akt activity by factors such as phosphatases (19) and microRNAs (51); the possibility that B. cenocepacia differentially affects these regulators requires examination.

As well as differences in PI3K/Akt-mediated regulation of NF-κB, the role of GSK3β is also variable, depending upon a number of factors such as TLR activation and cell type (52). GSK3β has been shown to inhibit NF-κB activity (35–37), yet has also been shown to be required for NF-κB activation (34). Hence, it is conceivable that factors specific to B. cenocepacia influence not only the mode of PI3K/Akt-mediated NF-κB activation but also the role of GSK3β.

In this study we find that PI3K/Akt does not influence the uptake or replication of B. cenocepacia within macrophages. PI3K inhibition by wortmannin has been reported to inhibit intracellular replication of B. cenocepacia within epithelial cells (23), presumably through an effect on autophagy. The difference between these findings may be reflective of macrophage versus epithelial cell or even LY294002 versus wortmannin pan-PI3K inhibition. However, we also find through genetic means that Akt does not influence macrophage phagocytosis or intra-macrophage replication of B. cenocepacia. Thus PI3K and Akt both strongly influence the macrophage inflammatory response without affecting B. cenocepacia uptake or survival.

One critical aspect related to this finding is that B. cenocepacia BC7, representing the virulent ET12 lineage that is associated with cepacia syndrome-related deaths, directly binds to the TNF receptor (TNFR1) to induce MAPK activation and IL-8 production (53). Importantly, one of the major effects of TNFR1 activation is activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB (54). This current study was done with the K56-2 isolate which too represents the highly virulent ET12 lineage (12). This strongly suggests that inhibition of PI3K/Akt may be an ideal therapeutic strategy to combat cepacia syndrome, as it regulates NF-κB at a point downstream of initial IKK activation. As such, it would be effective even against this TNFR-driven inflammatory response.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Steven Justiniano and Payal Mehta for the isolation of human monocytes, as well as Oliver Knoell for assistance with experiments. We acknowledge Jim Woodgett (Ontario Cancer Institute, Toronto, Ontario) for providing the GSK3β plasmid through Addgene, Philip Tsichlis (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA) for providing the NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid, and Amal Amer (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) for kindly providing stocks of Burkholderia cenocepacia.

This work was sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research (RCE) Program. The authors wish to acknowledge membership within and support from the Region V ‘Great Lakes’ RCE (NIH award 1-U54-AI-057153). This work was also sponsored by NIH/NIAID award # 1-T32-AI-065411, a NRSA training grant administered by the Center for Microbial Interface Biology (CMIB), at The Ohio State University, supporting T.J.C. J.P.B. is supported by the American Cancer Society Ohio Division Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Reference List

- 1.Valvano MA. Infections by Burkholderia spp.: the psychodramatic life of an opportunistic pathogen. Future Microbiol. 2006;1:145–149. doi: 10.2217/17460913.1.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sajjan U, Corey M, Humar A, Tullis E, Cutz E, Ackerley C, Forstner J. Immunolocalisation of Burkholderia cepacia in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. J Med Microbiol. 2001;50:535–546. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-6-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones AM, Dodd ME, Webb AK. Burkholderia cepacia: current clinical issues, environmental controversies and ethical dilemmas. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:295–301. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17202950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGowan JE., Jr Resistance in nonfermenting gram-negative bacteria: multidrug resistance to the maximum. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:S29–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.05.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson RL, Burns JL, Ramsey BW. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:918–951. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-505SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Govan JR, Hughes JE, Vandamme P. Burkholderia cepacia: medical, taxonomic and ecological issues. J Med Microbiol. 1996;45:395–407. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-6-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zughaier SM, Ryley HC, Jackson SK. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Burkholderia cepacia is more active than LPS from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in stimulating tumor necrosis factor alpha from human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1505–1507. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1505-1507.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazachkov M, Lager J, LiPuma J, Barker PM. Survival following Burkholderia cepacia sepsis in a patient with cystic fibrosis treated with corticosteroids. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;32:338–340. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ventura GM, Balloy V, Ramphal R, Khun H, Huerre M, Ryffel B, Plotkowski MC, Chignard M, Si-Tahar M. Lack of MyD88 protects the immunodeficient host against fatal lung inflammation triggered by the opportunistic bacteria Burkholderia cenocepacia. J Immunol. 2009;183:670–676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de CV, Le Goffic R, Balloy V, Plotkowski MC, Chignard M, Si-Tahar M. TLR 5, but neither TLR2 nor TLR4, is involved in lung epithelial cell response to Burkholderia cenocepacia. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;54:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blohmke CJ, Victor RE, Hirschfeld AF, Elias IM, Hancock DG, Lane CR, Davidson AG, Wilcox PG, Smith KD, Overhage J, Hancock RE, Turvey SE. Innate immunity mediated by TLR5 as a novel antiinflammatory target for cystic fibrosis lung disease. J Immunol. 2008;180:7764–7773. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sajjan SU, Carmody LA, Gonzalez CF, LiPuma JJ. A type IV secretion system contributes to intracellular survival and replication of Burkholderia cenocepacia. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5447–5455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00451-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamad MA, Skeldon AM, Valvano MA. Construction of aminoglycoside-sensitive Burkholderia cenocepacia strains for use in studies of intracellular bacteria with the gentamicin protection assay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3170–3176. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03024-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamothe J, Valvano MA. Burkholderia cenocepacia-induced delay of acidification and phagolysosomal fusion in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-defective macrophages. Microbiology. 2008;154:3825–3834. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/023200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saini LS, Galsworthy SB, John MA, Valvano MA. Intracellular survival of Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates in the presence of macrophage cell activation. Microbiology. 1999;145(Pt 12):3465–3475. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-12-3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Soyza A, Ellis CD, Khan CM, Corris PA, Demarco dH. Burkholderia cenocepacia lipopolysaccharide, lipid A, and proinflammatory activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:70–77. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-592OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palfreyman RW, Watson ML, Eden C, Smith AW. Induction of biologically active interleukin-8 from lung epithelial cells by Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia products. Infect Immun. 1997;65:617–622. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.617-622.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hazeki K, Nigorikawa K, Hazeki O. Role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in innate immunity. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:1617–1623. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsa KV, Ganesan LP, Rajaram MV, Gavrilin MA, Balagopal A, Mohapatra NP, Wewers MD, Schlesinger LS, Gunn JS, Tridandapani S. Macrophage pro-inflammatory response to Francisella novicida infection is regulated by SHIP. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e71. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajaram MV, Ganesan LP, Parsa KV, Butchar JP, Gunn JS, Tridandapani S. Akt/Protein kinase B modulates macrophage inflammatory response to Francisella infection and confers a survival advantage in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:6317–6324. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajaram MV, Butchar JP, Parsa KV, Cremer TJ, Amer A, Schlesinger LS, Tridandapani S. Akt and SHIP modulate Francisella escape from the phagosome and induction of the Fas-mediated death pathway. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butchar JP, Cremer TJ, Clay CD, Gavrilin MA, Wewers MD, Marsh CB, Schlesinger LS, Tridandapani S. Microarray analysis of human monocytes infected with Francisella tularensis identifies new targets of host response subversion. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sajjan US, Yang JH, Hershenson MB, LiPuma JJ. Intracellular trafficking and replication of Burkholderia cenocepacia in human cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1456–1466. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He X, Saint-Jeannet JP, Woodgett JR, Varmus HE, Dawid IB. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 and dorsoventral patterning in Xenopus embryos. Nature. 1995;374:617–622. doi: 10.1038/374617a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katso R, Okkenhaug K, Ahmadi K, White S, Timms J, Waterfield MD. Cellular function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases: implications for development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:615–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thimmaiah KN, Easton JB, Germain GS, Morton CL, Kamath S, Buolamwini JK, Houghton PJ. Identification of N10-substituted phenoxazines as potent and specific inhibitors of Akt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31924–31935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507057200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganesan LP, Wei G, Pengal RA, Moldovan L, Moldovan N, Ostrowski MC, Tridandapani S. The serine/threonine kinase Akt Promotes Fc gamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis in murine macrophages through the activation of p70S6 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54416–54425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408188200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khelef N, Shuman HA, Maxfield FR. Phagocytosis of wild-type Legionella pneumophila occurs through a wortmannin-insensitive pathway. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5157–5161. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.5157-5161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tachado SD, Samrakandi MM, Cirillo JD. Non-opsonic phagocytosis of Legionella pneumophila by macrophages is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karin M, Yamamoto Y, Wang QM. The IKK NF-kappa B system: a treasure trove for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:17–26. doi: 10.1038/nrd1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakurai H, Chiba H, Miyoshi H, Sugita T, Toriumi W. IkappaB kinases phosphorylate NF-kappaB p65 subunit on serine 536 in the transactivation domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30353–30356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gross S, Piwnica-Worms D. Real-time imaging of ligand-induced IKK activation in intact cells and in living mice. Nat Methods. 2005;2:607–614. doi: 10.1038/nmeth779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoeflich KP, Luo J, Rubie EA, Tsao MS, Jin O, Woodgett JR. Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in cell survival and NF-kappaB activation. Nature. 2000;406:86–90. doi: 10.1038/35017574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saijo K, Winner B, Carson CT, Collier JG, Boyer L, Rosenfeld MG, Gage FH, Glass CK. A Nurr1/CoREST pathway in microglia and astrocytes protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation-induced death. Cell. 2009;137:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Escribano C, Delgado-Martin C, Rodriguez-Fernandez JL. CCR7-dependent stimulation of survival in dendritic cells involves inhibition of GSK3beta. J Immunol. 2009;183:6282–6295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vines A, Cahoon S, Goldberg I, Saxena U, Pillarisetti S. Novel anti-inflammatory role for glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in the inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha- and interleukin-1beta-induced inflammatory gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16985–16990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutherland C, Cohen P. The alpha-isoform of glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle is inactivated by p70 S6 kinase or MAP kinase-activated protein kinase-1 in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1994;338:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutherland C, Leighton IA, Cohen P. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta by phosphorylation: new kinase connections in insulin and growth-factor signalling. Biochem J. 1993;296(Pt 1):15–19. doi: 10.1042/bj2960015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coghlan MP, Culbert AA, Cross DA, Corcoran SL, Yates JW, Pearce NJ, Rausch OL, Murphy GJ, Carter PS, Roxbee CL, Mills D, Brown MJ, Haigh D, Ward RW, Smith DG, Murray KJ, Reith AD, Holder JC. Selective small molecule inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 modulate glycogen metabolism and gene transcription. Chem Biol. 2000;7:793–803. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madrid LV, Wang CY, Guttridge DC, Schottelius AJ, Baldwin AS, Jr, Mayo MW. Akt suppresses apoptosis by stimulating the transactivation potential of the RelA/p65 subunit of NF-kappaB. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1626–1638. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1626-1638.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozes ON, Mayo LD, Gustin JA, Pfeffer SR, Pfeffer LM, Donner DB. NF-kappaB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gustin JA, Ozes ON, Akca H, Pincheira R, Mayo LD, Li Q, Guzman JR, Korgaonkar CK, Donner DB. Cell type-specific expression of the IkappaB kinases determines the significance of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling to NF-kappa B activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1615–1620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sizemore N, Leung S, Stark GR. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in response to interleukin-1 leads to phosphorylation and activation of the NF-kappaB p65/RelA subunit. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4798–4805. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandyopadhaya A, Bhowmick S, Chaudhuri K. Activation of proinflammatory response in human intestinal epithelial cells following Vibrio cholerae infection through PI3K/Akt pathway. Can J Microbiol. 2009;55:1310–1318. doi: 10.1139/w09-093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haller D, Russo MP, Sartor RB, Jobin C. IKK beta and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt participate in non-pathogenic Gram-negative enteric bacteria-induced RelA phosphorylation and NF-kappa B activation in both primary and intestinal epithelial cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38168–38178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sousa SA, Ulrich M, Bragonzi A, Burke M, Worlitzsch D, Leitao JH, Meisner C, Eberl L, Sa-Correia I, Doring G. Virulence of Burkholderia cepacia complex strains in gp91phox−/− mice. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2817–2825. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hii CS, Sun GW, Goh JW, Lu J, Stevens MP, Gan YH. Interleukin-8 induction by Burkholderia pseudomallei can occur without Toll-like receptor signaling but requires a functional type III secretion system. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1537–1547. doi: 10.1086/587905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wiersinga WJ, van der PT, White NJ, Day NP, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis: insights into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:272–282. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cremer TJ, Ravneberg DH, Clay CD, Piper-Hunter MG, Marsh CB, Elton TS, Gunn JS, Amer A, Kanneganti TD, Schlesinger LS, Butchar JP, Tridandapani S. MiR-155 induction by F. novicida but not the virulent F. tularensis results in SHIP down-regulation and enhanced pro-inflammatory cytokine response. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beurel E, Michalek SM, Jope RS. Innate and adaptive immune responses regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) Trends Immunol. 2010;31:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sajjan US, Hershenson MB, Forstner JF, LiPuma JJ. Burkholderia cenocepacia ET12 strain activates TNFR1 signalling in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:188–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen G, Goeddel DV. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science. 2002;296:1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.