Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease characterized by infiltration of pathogenic immune cells in the central nervous system resulting in destruction of the myelin sheath and surrounding axons. We and others have previously measured the frequency of human myelin reactive T cells in peripheral blood was observed. Using T cell cloning techniques, a modest increase in the frequency of myelin reactive T cells in patients as compared to control subjects. Here, we investigated whether MOG-specific T cells could be detected and their frequency measured using DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramers in MS subjects and healthy controls expressing HLA Class II DRB1*0401. We defined the optimal culture conditions for expansion of MOG reactive T cells upon MOG peptide stimulation of PMBC. MOG97–109 reactive CD4+ T cells, isolated with DRB1*0401/MOG97–109 tetramers, after a short-term culture of PMBC with MOG97–109 peptides were detected more frequently from patients with MS as compared to healthy controls. T cell clones from single cell cloning of DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer positive cells confirmed that these T cell clones were responsive to both the native and the substituted MOG peptide. These data indicate that autoantigen-specific T cells can be detected and enumerated from the blood of subjects utilizing Class II tetramers and the frequency of MOG97–109 reactive T cells is greater in patients with MS as compared to healthy controls.

Keywords: Human, Class II tetramers, myelin, autoimmunity, T lymphocytes

Introduction

MS is a genetically mediated autoimmune disease of the central nervous system with loss of neurologic function (1–3). Specifically, focal T cell and macrophage infiltrates result in demyelination and loss of surrounding axons (4). It is postulated that T cell recognition of peptides derived from myelin proteins in the context of MHC presented by microglia is involved in the disease’s pathogenesis. Autoreactive T cells are found at approximately the same frequency in normal individuals and patients with MS (5–8), though in subjects with the disease, autoreactive T cells are in a more activated state as compared to T cells from normal individuals (9–11). While the underlying etiology for the dysregulated immune system in MS is not known, fully replicated genome wide association scans have identified a number of allelic variants in immune related genes including IL2RA, IL7R, CD58, CD226, CD6, IRF8 and MHC class II that are associated with MS susceptibility (12, 13).

We first identified T cell epitopes of myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein in both patients with MS and healthy controls over two decades ago and have demonstrated minor differences in the frequency of antigen reactive cells in patients as compared to controls (6–8, 11, 14, 15); these autoreactive T cells can persist over long periods of time in patients (16, 17). Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) is another potentially important autoreactive T cell target in MS patients with epitopes identified that are restricted in the context of HLA DRB1*0401 and HLA DRB1*1501 (18–22).

Detecting myelin reactive T cells and monitoring their frequency in the peripheral blood has been a difficult task for a number of reasons. First, there is non-specific proliferation due to bystander activation of antigen non-reactive T cells. Second, perhaps a more difficult issue is the rarity of circulating autoreactive T cells and the need to first stimulate with myelin antigens (23–25) to detect their presence followed by non-specific readouts of function such as 3H-thymidine incorporation or cytokine secretion. This need for primary stimulation is not seen with HLA class I tetramers which have been a useful tool to detect and characterize antigen specific CD8 cells at the single cell level in a variety of studies including infectious diseases, cancers and type 1 diabetes (26–29). Finally, another hindrance to the use of MHC class II tetramers is the low T-cell receptor-MHC avidity particularly for self-antigen. In this regard, hemagglutinin A peptide reactive-, proinsulin reactive-, or GAD65-peptide reactive T cells with specific peptide loaded HLA DRB1*0401 tetramers and other Class II tetramers have been detected (30–42), though because of low autoreactive T cell frequency, expansion with autoantigen was necessary prior to T cell detection with tetramer.

In this study, we used HLA-DRB1*0401 MHC class II tetramers loaded with an epitope of MOG and optimized culture conditions to detect these antigen reactive CD4+ T cells in patients with MS and control subjects. Similar to previous experience with peptides derived from the sequence of glutamic acid decarboxylase in the investigation of antigen reactive CD4 cells in patients with type 1 diabetes (36), we utilized a MOG peptide (MOG97–109(107E-S)) which has a greater binding affinity to DRB1*0401 than the native peptide in order to maximize detection of MOG-reactive CD4+ T cells with the DRB1*0401 tetramer. First, we demonstrated our ability to detect MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide reactive T cells after a short-term culture of PMBC obtained from patients with MS and healthy control subjects carrying the HLA DRB1*0401 allele. We found that CD4+ DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide tetramer positive cells were detected more frequently in cultures of PBMC from subjects with MS than from cultures from healthy control subjects. We also replicated this finding in a subset of subjects using the native MOG97–109 peptide loaded on DRB1*0401 tetramers. Finally, reactivity and specificity of CD4+CD25+ DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) peptidetetramer positive cells were confirmed by single cell sorting cells of this phenotype followed by in vitro expansion and interrogation for responses to the MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide, the native MOG peptide, and control peptides in the context of DRB1*0401. These data suggest that the DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide tetramer can be used to differentiate MS and healthy control subjects by measuring the frequency of autoreactivity of MOG97–109 peptide reactive T cells and that this reagent is useful in isolating specific MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide and MOG97–109 peptide reactive T cells. Clinical investigations using these MHC class II tetramers in significantly larger cohorts of patients in relationship to MRI scanning are indicated.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents

HL-1 media was supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 5 mM HEPES, and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.1 mM each non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (all from Lonza, Walkersville, MD), and 5% heat-inactivated human male AB serum (ITN, San Francisco, CA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Atlanta Biologics. Lonza (Walkersville, MD), All antibodies (anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD25), 7AAD, GolgiStop© and Vacutainer tubes were from BD (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Phytohemagglutinin (PHA-P) was obtained from Remel (Lenexa, KS). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), ionomycin, Trypan blue, DMSO (dimethylsulfoxide) and neuraminidase were obtained from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO). Human recombinant IL-2 (Tecin) was obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). Ficoll-Paque and [3H]thymidine from Amersham (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Viacount reagent was from Guava technologies (Guava tech Inc., Hayward, CA). CD4 negative selection kit was from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA). Peptides were synthesized and purified by New England Peptide (Gardner, MA), or provided by the Immune Tolerance Network. Antibodies to human Vβ chains were purchased from Beckman Coulter (Miami, FL).

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)

Consenting volunteers, either healthy subjects or multiple sclerosis patients (MS) (all from the MS Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), expressing HLA Class II DRB1*0401 were selected and blood from these donors was collected by venipuncture in 10 ml lithium heparin Vacutainer® tubes according to the guidelines and recommendations of Brigham and Women’s Hospital IRB. The average age of the patients with MS was 54±10 years (12 female/2 male) and for controls 41±13years (10 female/4 male), the two groups were matched except for two subjects (MS patients that were 73 and 76 years old). All patients were in the relapsing remitting phase of disease. For this phase I study, patients were on different treatments including sIFN, Glatiramer Acetate, and Daclizamab, though later analysis demonstrated no relationship between therapy and tetramer binding frequency. All tissue typing was performed at the Histocompatibility Laboratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. PMBC were isolated by standard Ficoll-Hypaque methods and were used either fresh or after cryopreservation in 10%DMSO/90% human AB serum and storage in liquid nitrogen.

Cell preparation

CD4+ T cells were purified from PMBC by negative selection using the Miltenyi Biotec CD4+ T cell isolation kit. The non-CD4 cells were incubated in 24-well plates at a density of 2.5 × 106/well for 2 h. Adherent cells were collected and used as antigen presenting cells (APC) and were loaded with the peptides for 2 hours with before plating CD4+ T cells (2.5 × 106/well) in flat bottom 12 well plates. The cells were cultured for 14 days in HL-1 medium containing 5% human serum. IL-2 (20 U/ml) was added on days 4, 7 and 10. The cultures were split in two wells and supplemented with fresh medium on day 7.

Tetramer preparation

The generation of DRB1*0401 soluble class II molecules has been described (43). The peptide MOG97–109 was used to load the DRB1*0401 molecule to generate the DRB1*0401/MOG97–109 tetramer. MOG97–109 peptide used here for tetramer construction (FFRDHSYQEEA-native sequence) has a mutation at position 107 (E-S) to stabilize binding to the DRB1*0401/DRA*0101 chains. The procedure for HA306–318 (PRYVKQNTLKLAT) and GAD65555–567 immunodominant epitope (NFFRMVISNPAAT, native sequence, the peptide used to load the DRB1*0401 tetramer has a substitution at position 555, F-I, to stabilize binding) peptide loading was identical to those described earlier (43), and were used to generate DRB1*0401/HA306–318 and DRB1*0401/GAD65555–567(557F-I) tetramers as control tetramers for staining. Streptavidin-phycoerythrin (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA) was used for cross-linking. All of the tetramers used for direct staining were filtered through a Sephadex G-50 size exclusion column before use.

Stimulation and tetramer staining

Cells were treated with or without 0.5 U/ml of neuraminidase (type X from C. perfringens) for 30 min at 37°C in HL-1 medium. The cells were washed with PBS, then stained with 10 μg/ml phycoerythrin-labeled tetramer (DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide or DRB1*0401/GAD65555–567(557F-I) at 37°C for 3 hours in HL-1 medium with 2% human serum. Cells were stained for the last 30 min with allophycocyanin-labeled anti-CD25 and FITC-anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies; dead cells were discriminated using 7AAD. After washing, the percentage of CD4+CD25intermediate tetramer positive cells was determined within the live cell gate (7AAD negative) by flow cytometry. The data was acquired on an LSR II (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Single cell cloning and specificity testing

CD4+CD25+DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer+7AAD- cells were single-cell sorted into 96 well plates using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Immunocytometry Systems). Clones thus obtained were expanded for 28 days by stimulation with irradiated unmatched PMBC in the presence of PHA-P (3 μg/ml) and IL-2 (20 units/ml) for two rounds. Clones were generated from 2 healthy control subjects and 1 MS subject, all bearing HLA DRB1*0401.

Proliferation assays

T-cell clones were washed twice and added to U-bottom 96-well plates at 25,000 cells/well. The Epstein Barr virus (EBV)-transformed B-cell line Priess, which is homozygous for DRB1*0401, was used as APC. Irradiated (5000 rads) APC were incubated with the peptides at 3×105 cells/ml for 2 h at 37°C. After washing, and resuspending the cells in the original volume, 100 μl were added to each well in duplicates. After 72 h, plates were pulsed with 1 μCi/well of [3H]thymidine to measure proliferation. Plates were harvested 16 h later to count the incorporated radioactivity (Wallac).

Statistical analysis of data

Statistical differences were calculated using Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) using an unpaired Student’s t-test.

Results

Detection of MOG97–109(107E-S) reactive T cells ex vivo and after in vitro culture

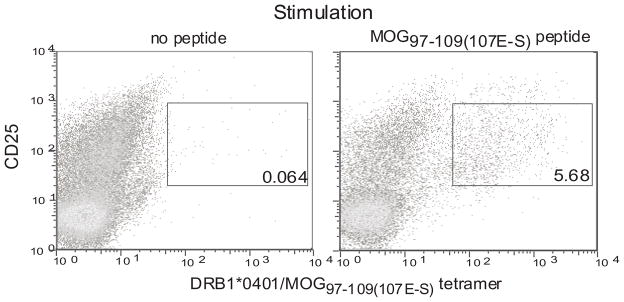

It has been previously shown that class II tetramers with modified glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD) peptide and modified proinsulin peptide can be used to detect GAD and proinsulin reactive T cells respectively in the peripheral blood of human subjects (32, 35, 41, 43, 44). Utilizing a similar strategy, we utilized a modified MOG peptide MOG97–109(107E-S). This peptide was designed with a 107E-S substitution at the P9 anchoring position such that it bound to DRB1*0401/DRA1*0101 MHC molecules with an affinity that was 50 fold higher compared to the wild type MOG97–109 peptide (Supplementary Fig. 1). We cultured PBMC from MS patients who expressed DRB1*0401 with the MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide for 14 days and examined whether the DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer could detect CD4+CD25intermediate T cells (activated CD4+ T cells) in the cultures (Fig. 1). Approximately 5% of the CD4+CD25intermediate T cells in culture bound the tetramer.

Figure 1. Detection of MOG97–109(107E-S) reactive T cells using DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer in a MOG peptide expanded culture.

Cryopreserved PMBC from a DRB1*0401 MS subject were thawed. CD4+ cells were isolated by negative selection and incubated with autologous adherent APC from the same donor loaded with or without 10μg/ml of MOG97–109(107E-S). The co-cultures were carried for 14 days in presence of recombinant human IL-2 (10 U/ml) on days 4, 7 and 10. The cells were stained with the DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer, anti-CD4, anti-CD25 and 7AAD and analyzed using an LSR II flow cytometer. Live (7-AAD negative) and CD4+ cells were gated upon and used to enumerate the percentage of CD25intermediateDRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer+ cells. This is a representative sample from four subjects examined.

Defining the optimal conditions for MOG specific cell detection in the peripheral blood

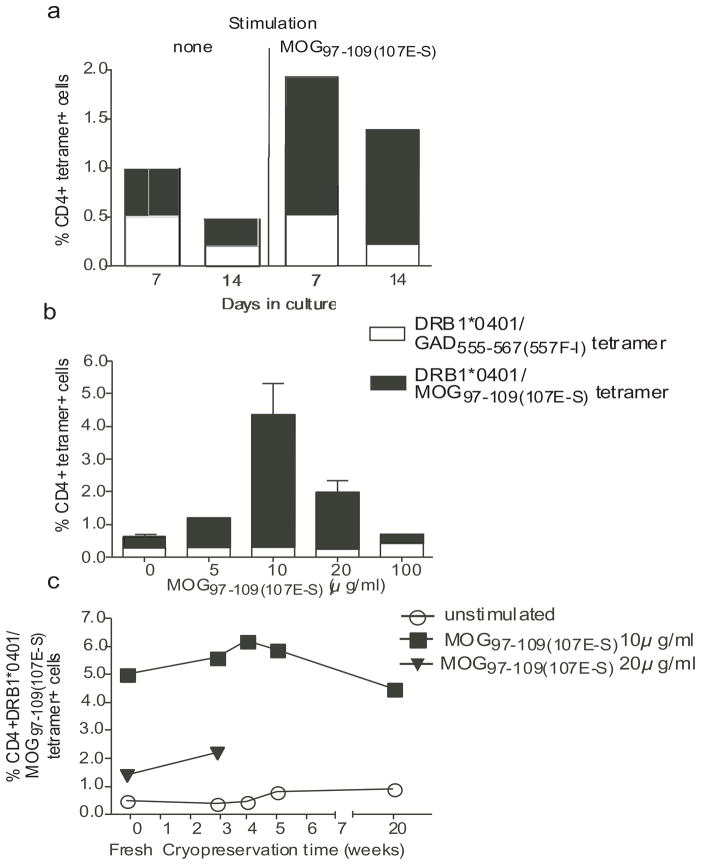

We performed a series of experiments to determine the optimal conditions for detecting MOG97–109(107E-S) reactive T cells. We examined parameters including the length of culture after stimulation, dose-response to the MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide, comparison of fresh versus cryopreserved samples, and finally reproducibility of the assay. We compared the culture of CD4+ cells with MOG peptide and irradiated autologous adherent cells from the PBMC for seven as compared to 14 days in the presence of IL-2. We observed that 14 days of culture resulted in amplifying the number of MOG tetramer positive CD4 while decreasing the background staining (Fig. 2a). This culture period resulted in a better signal to noise ratio of specific tetramer binding to irrelevant tetramer (DRB1*0401/GAD65555–567(557F-I) binding (9.7 as compared to 4.0, respectively). We then examined a range of concentrations of MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide to determine optimal dose responses of MOG specific CD4 T cell expansion. As shown in Figure 2b, 10 μg/ml induced maximal MOG tetramer binding as compared to binding to irrelevant GAD tetramer.

Figure 2. Optimum conditions for DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer staining.

The conditions for optimal tetramer staining was determined using PMBC from two DRB1*0401 MS patients with respect to in vitro culture duration, concentration of MOG97–109(107E-S) in a 14 day in vitro assay, and evaluation of fresh versus frozen PMBC for various periods of time. Triple color FACS staining was conducted to include DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer-PE, CD4-APC, and 7-AAD. The percentage of tetramer positive cells was determined in the CD4 population by eliminating the 7-AAD-stained cells. The averages (+/− SD) from two samples are shown. In (a), the signal to noise ratio for cells stained with the specific tetramer (loaded with substituted MOG peptide) versus the irrelevant tetramer (loaded with the GAD peptide) was best at Day 14 of culture (ratio: 9.7) as compared to those at Day 7 of culture (ratio: 4.0). In 14 day cultures (b), the maximal number of DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer+ cells was detected with an initial peptide stimulation concentration of 10 μg/ml. In (c), the number of DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer+ cells was similar from fresh as compared to PBMC cryopreserved for various lengths of time in 14 day assays with the initial peptide stimulation of 10 μg/ml MOG97–109(107E-S).

The use of fresh blood samples in clinical investigations is cumbersome in multi-center studies involving different participating centers; moreover, in most studies there is a need for immune monitoring over time. For these reasons, samples are collected and cryopreserved for a determined time before testing. We examined whether the detection of DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer positive cells was affected in cryopreserved PBMC samples as compared to fresh sample. Using an optimal cryopreservation protocol for PMBC developed by the Immune Tolerance Network (http://www.immunetolerance.org/professionals/research/lab-protocols) that allowed for 95% viability and over 85% recovery, we did not find any significant decrease of the staining between fresh and cryopreserved PMBC that were kept in liquid nitrogen for 3, 4, 5 and 20 weeks prior to use (Fig. 2c).

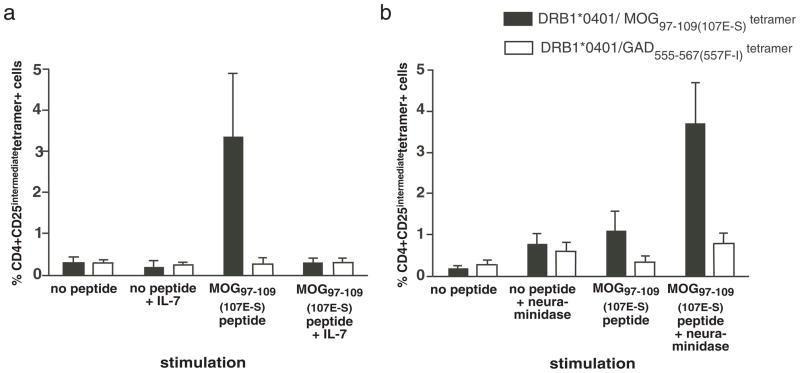

Effect of adding cytokines during the culture and treating with neuraminidase before tetramer staining

Since in vitro culture of PBMC with antigen and IL-2 expands antigen reactive T cells for detection, we examined whether IL-7, a T cell growth factor for memory T cells improved the detection of CD4+ DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer positive cells; surprisingly, we found that adding IL-7 to the cultures resulted in a decrease of the intensity of staining and the percentage of MOG tetramer positive cells (Fig. 3a). Neuraminidase treatment has been described to enhance CD4 tetramer staining of myelin specific T cells in a mouse model of MS (45) and tetramer staining of CD8+ T cells (46). We examined whether neuraminidase treatment increased DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer staining of human cells cultured with MOG97–109(107E-S). We observed an increase in tetramer staining after treating the cells with neuraminidase, though T cell staining of both the DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer and the irrelevant DRB1*0401/GAD65555–567(557F-I) tetramer was increased (signal to noise ratios 3.9 and 4.4, respectively (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Addition of IL-7 or treatment with neuraminidase decreases specific binding of the DRB1*0401 MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer to MOG97–109(107E-S) stimulated PBMC.

Cryopreserved PMBC from DRB1*0401 MS subjects were thawed. CD4+ cells were isolated by negative selection and incubated with autologous adherent APC from the same donor loaded with 10μg/ml of MOG97–109(107E-S). The co-cultures were carried for 14 days in presence of added IL-2 on day 4, 7 and 10. (a) IL-7 (5ng/ml) was added in the culture on the first day. (b) Cells were incubated with or without 0.5 U/ml of neuraminidase for 30 minutes at 37°C before staining with the tetramer and antibodies on Day 14. The cells were counterstained with anti-CD4, anti-CD25, and 7AAD. Data shown is the average (+/− standard error) of samples (n=4 for a, IL-7 addition, and n=5 for b, neuraminidase treatment).

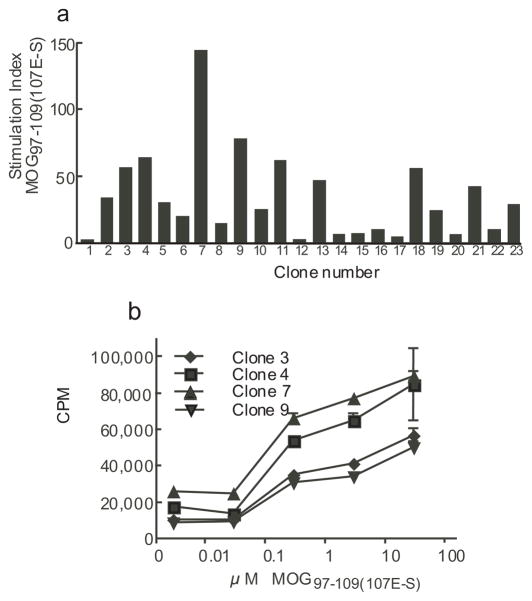

Cloning of MOG reactive CD4 cells and specificity testing

In order to demonstrate that cells binding to the DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer were specific, we cultured CD4+ cells from a MS patient with autologous APC loaded with MOG97–109(107E-S) (Fig. 1). After 14 days of stimulation we single cell cloned CD4+CD25intermediate DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer binding cells and expanded them with PHA and IL-2. After expanding clones in vitro, they were rested and then examined for antigen specificity by using irradiated Priess B cells (DRB1*0401+/+) pulsed with MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide. Twenty-three randomly chosen clones from 60 clones were examined for antigen reactivity as measured by tritiated thymidine incorporation. We found that 20/23 clones proliferated in response to the MOG97–109 (107E-S) peptide-loaded antigen presenting cells as defined by a stimulation index of ≥5 and a ΔCPM > 10,000 (Fig. 4a). We then examined the dose responses of four representative clones to MOG97–109(107E-S) generated by single cell cloning. These clones responded to the MOG peptide with an approximate EC50 dose (half-maximal effective concentration) of 1–10 μM (Fig. 4b). As these clones were derived using the MOG97–109(107E-S) substituted peptide, it was important to show that these clones proliferated in response to the native MOG97–109 peptide. The response of representative clones is shown in Table I. These clones responded to both the native and substituted MOG peptide with equivalent EC50 doses, but not to an irrelevant GAD65555–567(557F-I) peptide. The magnitude of the response to the substituted MOG peptide was greater than the response to the native peptide for the clones that were tested (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 4. Reactivity of T cell clones generated with the DRB1*0401/MOG97–109 tetramer.

T cell clones were generated by single cell cloning of CD4+CD25intermediateDRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer+ cells as described in methods. Irradiated Priess (DRB1*0401 +/+) B cells were pulsed with MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide for two hours, washed and plated at 10,000/well. T cell clones were added at 25,000 cells/well and incubated for 48 hours. Wells were then pulsed with 1 μCi/well of tritiated thymidine and harvested 28 hours later. The stimulation index (antigen pulsed culture CPM/no antigen pulsed culture CPM) of representative 23 clones is shown in (a); concentration of MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide in this experiment was 10 μM. A clone was considered to be positive to the peptide SI>5 (horizontal line) and ΔCPM>10,000. The dose response of 4 representative clones to the native MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide is shown in (b).

Table I. CD4+ T cell clones isolated with DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer responded to substituted and native MOG peptide.

T cell clones were assayed for reactivity to MOG97–108 (native), MOG97–109(107E-S), peptides, and GAD65555–567(557F-I) peptide as an irrelevant peptide with Priess cells (DRB1*0401+/+) as APC over a range of peptide concentrations, 0.1 to 100 μM. The EC50 for each clone responding to peptides was determined. Each clone responded to each MOG peptide with approximately the same EC50 while the magnitude of the response was greater to the substituted peptide and as compared to the response to the native peptide for 8/9 clones tested.

| EC50 μM | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clone number | MOG97–109(native) | MOG97–109(107E-S) | GAD65555–567(557F-I) |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | >100 |

| 4 | 10 | 10–30 | >100 |

| 7 | 5 | 5 | >100 |

| 6 | 10 | 10 | >100 |

| 9 | 5 | 8 | >100 |

| 11 | 5 | 5–10 | >100 |

| 18 | 10 | 5 | >100 |

| 21 | 5 | 5 | >100 |

| 23 | 7 | 10 | >100 |

Detection of CD4+DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer positive T cells after peptide-culture with PBMC from healthy controls and patients with multiple sclerosis

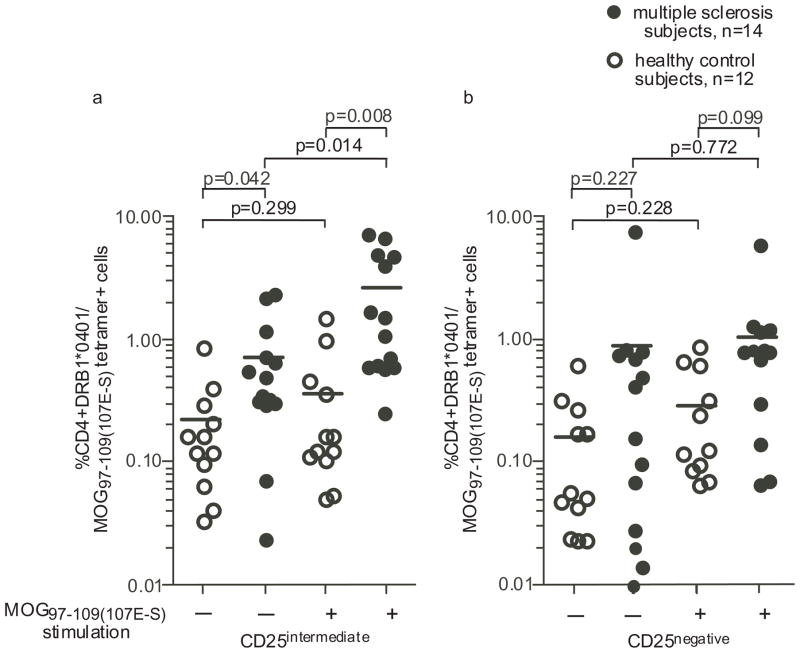

Finally, using the optimal conditions defined above, we examined whether there were differences in the frequency of autoreactive T cells after 14 days of culture with the MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide between 12 healthy control subjects and 14 patients with multiple sclerosis, all matched for expression of the DRB1*0401 allele. For these experiments, CD4+ cells were isolated by negative selection and cultured with autologous antigen presenting cells loaded with MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide in the presence of IL-2 added on day 4, 7 and 10. After 14 days of stimulation, the percentage of CD4+CD25intermediate DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer positive T cells were significantly higher in patients with multiple sclerosis as compared to healthy control subjects (Fig. 5a; p=0.008). We also examined the frequency of CD4+CD25intermediate DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer binding CD4 cells in the absence of antigen stimulation. Surprisingly, we observed a significant difference between healthy controls and patients with multiple sclerosis (p=0.042) after expansion for 14 days in the presence of IL-2 (Fig. 5a). The difference in the frequency of CD4+CD25− DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer binding CD4 cells between healthy control subjects and MS patients did not reach significance (Fig. 5b). These experiments were also conducted with HA306–318 peptide stimulation of PBMC, culture, and subsequent reactive T cell detection with DRB1*0401/HA306–318 tetramer; there was no difference in the frequencies of HA reactive T cells between multiple sclerosis and healthy control subjects (data not shown).

Figure 5. MOG97–109(107E-S) reactive T cells are more frequent after culture with MOG97–109(107E-S) from multiple sclerosis subjects than from healthy subjects.

Frequency of CD4+CD25intermediate DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) reactive T cells (a) was determined by flow cytometry after 14 days of culture with MOG97–109(107E-S) as described in methods. CD4+CD25negative DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer+ T cells were enumerated as a comparison (b). CD4+CD25intermediate DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) reactive T cells were more frequently detected from the MS patients after 14 day culture with or without MOG97–109(107E-S) stimulation. P values comparing data between groups are shown in the figure.

In order to demonstrate that CD4+ T cells detected with the DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer reacted with the native peptide, we examined PBMC from DRB1*0401+ healthy controls and MS subjects cultured with no peptide, native MOG peptide, or substituted MOG peptide and then enumerated the frequency of CD4+ T cells with the DRB1*0401 tetramer loaded with either the native or substituted peptide (Supplementary Fig. 3). Culture of PBMC from MS subjects with no peptide or culture of PBMC from healthy controls in any of these condition resulted in no detection of CD4+ T cell expansion with either tetramer (loaded with either the native or substituted peptide). However, culture of PBMC from MS subjects with either native or substituted peptide resulted in expansion of CD4+ T cells binding the tetramer loaded with either the native or substituted peptide. This detection was greatest when PBMC were cultured with substituted MOG peptide and detected with the DRB1*0401/MOG97–109(107E-S) tetramer. To verify that the difference observed between MS and healthy using the substituted MOG was relevant to MOG and not just due to an altered peptide ligand effect, we examined the frequency of CD4+CD25intermediate DRB1*0401/MOG97–109 tetramer positive T cells in healthy subjects and patients with MS using the native MOG97–109 to stimulate the cells and the DRB1*0401/MOG97–109 loaded tetramer to detect reactive cells. We were able to confirm that the frequency of DRB1*0401/MOG97–109 was significantly higher in patients with multiple sclerosis as compared to healthy control subjects (Supplementary Fig. 4).

We analyzed the Vβ chain of a panel of CD4 clones by flow cytometry and found that each clone expressed a single Vβ chain type suggesting their clonality. Among the different clones we found a normal distribution of expressed Vβ chains, indicating that there is no preference for one type of Vβ chains for reactivity to hemagglutinin or MOG (data not shown).

Discussion

Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory disease of the central nervous system. It fits into the group of autoimmune diseases that share allelic variations in common gene regions including the MHC locus, IL-2RA, IL-7R, and CD226 (12, 13). However, it has been difficult to demonstrate differences in the frequency of myelin specific T cells in the circulation of patients with the disease. An early study showed higher frequency of anti-MOGIgd in the serum of MS patients, but no difference in the T cell proliferative response between healthy subjects and patients with MS (50). A more recent report by Bahbouhi et al. has shown using a sensitive detection method, increased frequencies of anti-myelin T cells in MS patients (51). Soluble MHC-peptide complexes allow the detection and isolation of antigen-specific T cells (26) and these recombinant MHC class II tetramers have been successfully used to detect antigen-specific CD4+ T cells for viral, bacterial and self-antigens (30–42). Here we successfully applied this approach to demonstrate increases in the frequency of myelin specific T cells in patients with MS as compared to healthy controls using HLA-DRB1*0401 class II tetramers loaded with MOG peptide.

Several staining conditions were also evaluated to provide optimal tetramer staining. One factor shown to influence tetramer detection of autoreactive T cells is the presence of moieties of sialic acid on cell surface proteins (45). It has been suggested that removal of sialic acid by neuraminidase treatment results in reduction of net cell charge in the interacting populations with increased membrane fluidity leading to enhanced cell-tetramer adhesiveness (45, 46). In contrast to previous reports, we observed that neuraminidase treatment increased the percentage of tetramer binding cells, however, it also increased non-specific binding of irrelevant tetramers to CD4+ cells. This may indicate that the modifications to proteins on the cell surface differ between species or for this particular binding interaction.

As IL-7 has been shown by our group (unpublished data) and others to increase the proliferation and cytokine production of antigen reactive T cells (47, 52, 53), we examined whether this growth factor improved the expansion of MOG reactive cells. Instead, we found that the addition of IL-7 to the culture decreased tetramer staining which may be due to a decreased affinity of the TCR or a down-regulation of the TCR. We also observed that tetramer staining was best observed in cells corresponding to the CD4+CD25intermediate subset that includes memory CD4 cells.

MOG97–109 has been identified as a major target of T cells in subjects with the DRB1*0401 allele (18–21). We utilized the higher affinity binding of the substituted MOG peptide for DRB1*0401 in order to promote and stabilize binding of the peptide-MHC tetramer to the T cells as quantitative enumeration of antigen-specific T cells by tetramer staining, particularly at low frequencies, critically depends on the quality of the tetramers and on the staining procedures. Specifically, suboptimal class II tetramer staining can be due to the low binding affinity of the MOG peptide to the class II molecule. As discussed above, we designed a modified MOG97–109(107E-S) peptide with an E-S substitution which provided an optimal P9 anchoring position for DRB1*0401/DRA1*0101 binding. This peptide bound to DRB1*0401 with a significantly higher affinity compared to the wild type peptide.

To confirm that the CD4 cells binding to MOG tetramer produced with this modified peptide were indeed antigen specific T cells, we directly examined the reactivity and specificity of the tetramer binding cells by single cell sorting and cloning of tetramer positive populations followed by in vitro expansion of clones and testing reactivity with peptides in the context of DRB1*0401. The MOG97–109(107E-S) reactive T cell clones derived in this manner had approximate EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration for reactivity) values of 1–10 μM of peptide. The MOG97–109 peptide used here for tetramer construction (FFRDHSYQEEA-native sequence) has a mutation at position 107 (E-S) to stabilize binding to the DRB1*0401/DRA*0101 molecules. Thus, it was important to demonstrate that the T cells clones also had reactivity to the native peptide sequence (Table 1). As can be seen, the EC50 for each clone’s reactivity to the native or substituted peptide is approximately equivalent though the proliferative responses were less. The native peptide loaded in tetramer resulted in binding of CD4+ cells to the tetramer after culture with either native or the higher affinity peptide; however, in all the MS samples examined, the frequency of tetramer binding cells detected was increased when PBMC were cultured with the substituted peptide and detected with the tetramer loaded with substituted peptide. Most importantly, we detected little tetramer staining in the PBMC from the healthy controls and the MOG clones generated responded to both the substituted and the native MOG.

Limiting dilution frequency analysis has suggested that autoreactive T cells are found at approximately the same frequency in normal individuals as compare to patients with MS (5–8, 17). However, in subjects with MS, autoreactive T cells are in a more activated state as compared to T cells from normal individuals (9–11). Recently, the relative frequency and avidity of autoreactive CD4+ T cells to GAD65 from PBMC samples from subjects at risk to type 1 diabetes and then after diagnosis for type 1 diabetes was followed using in vitro culture of PBMC and detection of autoreactive T cells with DRB1*0401/GAD65555–567(557F-I) tetramer (48). In addition, the recurrence of T cell autoimmunity in Type 1 diabetes patients who underwent pancreas-kidney transplants with immunosuppression was detected with DRB1*0401/GAD65555–567(557F-I) tetramer reagents (49). These data indicate that self-peptide loaded tetramer reagents are useful in following disease course and for generating information on the frequency and avidity of the T cell response to that antigen. We used the optimal tetramer conditions defined in this investigation and were able to detect MOG reactive T cells in the peripheral blood after 14 days in vitro expansion in the presence of IL-2. As expected, MOG reactive T cells were present in both healthy control and patients with MS; however, their frequency after culture with the peptide was higher in the MS population. We speculate that these culture conditions selectively allowed detection of MOG reactive T cells that were either more activated or resistant to apoptosis. The ability to detect a difference in the frequency of MOG reactive T cells in patients as compared to controls will allow future investigations to better elucidate the biologic characteristics of autoreactive T cells in the disease.

In summary, we have defined an MHC II tetramer system using a mutated MOG peptide (MOG97–109(107E-S)) that allowsus to detect MOG97–109(107E-S) reactive T cells from subjects bearing the DRB1*0401 allele. Even though the detection was better using the substituted MOG97–109(107E-S), we were able to detect a higher frequency of tetramer reactive cells from patients with MS as compared to healthy control using either the substituted or the native MOG. The parameters of culture are especially important when detecting rare antigen-specific T cells in the naive repertoire or in detecting low-avidity autoreactive T cells. MOG97–109 reactive T cells are present in the peripheral blood of both healthy control and MS subjects, but the frequency in patients was higher after 14 day of culture even without MOG peptide stimulation. The clones generated from MS subjects showed reactivity with the native and substituted MOG97–109 peptide and showed specificity to that peptide. These strategies may be adapted for the detection of rare antigen-specific low-avidity autoreactive T cells in vivo for detecting the evolution of the autoreactive repertoire and following the phenotype of autoreactive T cells in the course of the autoimmune disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Deneen Kozoriz for assisting in cell sorting experiments and the personnel of the MS clinic for providing us with the blood samples.

These studies were supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health to D.A.H. (P01 AI045757, U19 AI046130, U19 AI070352, P01 AI039671), S.C.K. and E.M.B. are supported by grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International. K.R. was supported by a grant from the Immune Tolerance Network. D.A.H. is also supported by a Jacob Javits Merit Award (NS2427) from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Abbreviations

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- GAD65

glutamic acid decarboxylase 65

Literature cited

- 1.Agrawal SM, V, Yong W. Immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. International Review of Neurobiology. 2007;79:99–126. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)79005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minagar A, Carpenter A, Alexander JS. The destructive alliance: interactions of leukocytes, cerebral endothelial cells, and the immune cascade in pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. International Review of Neurobiology. 2007;79:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)79001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterson JW, Trapp BD. Neuropathobiology of multiple sclerosis. Neurologic Clinics. 2005;23:107–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hafler DA, Slavik JM, Anderson DE, O’Connor KC, De Jager P, Baecher-Allan C. Multiple sclerosis. Immunological Reviews. 2005;204:208–231. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin R, Howell MD, Jaraquemada D, Flerlage M, Richert J, Brostoff S, Long EO, McFarlin DE, McFarland HF. A myelin basic protein peptide is recognized by cytotoxic T cells in the context of four HLA-DR types associated with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 1991;173:19–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ota K, Matsui M, Milford EL, Mackin GA, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. T-cell recognition of an immunodominant myelin basic protein epitope in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 1990;346:183–187. doi: 10.1038/346183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pette M, Fujita K, Kitze B, Whitaker JN, Albert E, Kappos L, Wekerle H. Myelin basic protein-specific T lymphocyte lines from MS patients and healthy individuals. Neurology. 1990;40:1770–1776. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.11.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wucherpfennig K, Zhang J, Witek C, Matsui M, Modabber Y, Ota K, Hafler D. Clonal expansion and persistence of human T cells specific for an immunodominant myelin basic protein peptide. Journal of Immunology. 1994;152:5581–5592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovett-Racke AE, Trotter JL, Lauber J, Perrin PJ, June CH, Racke MK. Decreased dependence of myelin basic protein-reactive T cells on CD28-mediated costimulation in multiple sclerosis patients. A marker of activated/memory T cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101:725–730. doi: 10.1172/JCI1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholz C, Patton KT, Anderson DE, Freeman GJ, Hafler DA. Expansion of autoreactive T cells in multiple sclerosis is independent of exogenous B7 costimulation. Journal of Immunology. 1998;160:1532–1538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, Markovic-Plese S, Lacet B, Raus J, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Increased frequency of interleukin 2-responsive T cells specific for myelin basic protein and protolipid protein in peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;179:973–984. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Jager PL, Jia X, Wang J, de Bakker PI, Ottoboni L, Aggarwal NT, Piccio L, Raychaudhuri S, Tran D, Aubin C, Briskin R, Romano S, Baranzini SE, McCauley JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL, Gibson RA, Naeglin Y, Uitdehaag B, Matthews PM, Kappos L, Polman C, McArdle WL, Strachan DP, Evans D, Cross AH, Daly MJ, Compston A, Sawcer SJ, Weiner HL, Hauser SL, Hafler DA, Oksenberg JR Consortium., I. M. G. Meta-analysis of genome scans and replication identify CD6, IRF8 and TNFRSF1A as new multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:776–782. doi: 10.1038/ng.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Consortium., I. M. S. G. Hafler DA, Compston A, Sawcer S, Lander ES, Daly MJ, De Jager PL, de Bakker PI, Gabriel SB, Mirel DB, Ivinson AJ, Pericak-Vance MA, Gregory SG, Rioux JD, McCauley JL, Haines JL, Barcellos LF, Cree B, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL. Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genomewide study. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:851–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaraquemada D, Martin R, Rosen-Bronson S, Flerlage M, McFarland HF, Long EO. HLA-DR2a is the dominant restriction molecule for the cytotoxic T cell response to myelin basic protein in DR2Dw2 individuals. Journal of Immunology. 1990;145:2880–2885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wucherpfennig KW, Sette A, Southwood S, Oseroff C, Matsui M, Strominger JL, Hafler DA. Structural requirements for binding of an immunodominant myelin basic protein peptide to DR2 isotypes and for its recognition by human T cell clones. J Exp Med. 1994;179:279–290. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bieganowska KD, Ausubel LJ, Modabber Y, Slovik E, Messersmith W, Hafler DA. Direct ex vivo analysis of activated, Fas-sensitive autoreactive T cells in human autoimmune disease. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1997;185:1585–1594. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong J, Zang YC, Li S, Rivera VM, Zhang JZ. Ex vivo detection of myelin basic protein-reactive T cells in multiple sclerosis and controls using specific TCR oligonucleotide probes. European Journal of Immunology. 2004;34:870–881. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forsthuber TG, Shive CL, Wienhold W, de Graaf K, Spack EG, Sublett R, Melms A, Kort J, Racke MK, Weissert R. T cell epitopes of human myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein identified in HLA-DR4 (DRB1*0401) transgenic mice are encephalitogenic and are presented by human B cells. Journal of Immunology. 2001;167:7119–7129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerlero de Rosbo N, Hoffman M, Mendel I, Yust I, Kaye J, Bakimer R, Flechter S, Abramsky O, Milo R, Karni A, Ben-Nun A. Predominance of the autoimmune response to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) in multiple sclerosis: reactivity to the extracellular domain of MOG is directed against three main regions. European Journal of Immunology. 1997;27:3059–3069. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koehler NK, Genain CP, Giesser B, Hauser SL. The human T cell response to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein: a multiple sclerosis family-based study. Journal of Immunology. 2002;168:5920–5927. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linington C, Berger T, Perry L, Weerth S, Hinze-Selch D, Zhang Y, Lu HC, Lassmann H, Wekerle H. T cells specific for the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein mediate an unusual autoimmune inflammatory response in the central nervous system. European Journal of Immunology. 1993;23:1364–1372. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallström E, Khademi M, Andersson M, Weissert R, Linington C, Olsson T. Increased reactivity to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptides and epitope mapping in HLA DR2(15)+ multiple sclerosis. European Journal of Immunology. 1998;28:3329–3335. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199810)28:10<3329::AID-IMMU3329>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hafler DA, Benjamin DS, Burks J, Weiner HL. Myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein reactivity of brain- and cerebrospinal fluid-derived T cell clones in multiple sclerosis and postinfectious encephalomyelitis. Journal of Immunology. 1987;139:68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCutcheon M, Wehner N, Wensky A, Kushner M, Doan S, Hsiao L, Calabresi P, Ha T, Tran TV, Tate KM, Winkelhake J, Spack EG. A sensitive ELISPOT assay to detect low-frequency human T lymphocytes. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1997;210:149–166. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Söderström M, Link H, Sun JB, Fredrikson S, Kostulas V, Höjeberg B, Li BL, Olsson T. T cells recognizing multiple peptides of myelin basic protein are found in blood and enriched in cerebrospinal fluid in optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis. Scandinavian Journla of Immunology. 1993;37:355–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1993.tb02565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altman JD, Moss PA, Goulder PJ, Barouch DH, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Bell JI, McMichael AJ, Davis MM. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274:94–96. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Vries IJ, Bernsen MR, van Geloof WL, Scharenborg NM, Lesterhuis WJ, Rombout PD, Van Muijen GN, Figdor CG, Punt CJ, Ruiter DJ, Adema GJ. In situ detection of antigen-specific T cells in cryo-sections using MHC class I tetramers after dendritic cell vaccination of melanoma patients. Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy. 2007;56:1667–1676. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0304-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SK, Devine L, Angevine M, DeMars R, Kavathas PB. Direct detection and magnetic isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein-specific CD8+ CTLs with HLA class I tetramers. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165:7285–7292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skowera A, Ellis RJ, Varela-Calviño R, Arif S, Huang GC, Van-Krinks C, Zaremba A, Rackham C, Allen JS, Tree TI, Zhao M, Dayan CM, Sewell AK, Unger WW, Drijfhout JW, Ossendorp F, Roep BO, Peakman M. CTLs are targeted to kill beta cells in patients with type 1 diabetes through recognition of a glucose-regulated preproinsulin epitope. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118:3390–3402. doi: 10.1172/JCI35449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gebe JA, Falk BA, Rock KA, Kochik SA, Heninger AK, Reijonen H, Kwok WW, Nepom GT. Low-avidity recognition by CD4+ T cells directed to self-antigens. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1409–1417. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laughlin E, Burke G, Pugliese A, Falk B, Nepom G. Recurrence of autoreactive antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in autoimmune diabetes after pancreas transplantation. Clinical Immunology. 2008;128:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.03.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mallone R, Kochik SA, Reijonen H, Carson B, Ziegler SF, Kwok WW, Nepom GT. Functional avidity directs T-cell fate in autoreactive CD4+ T cells. Blood. 2005;106:2798–2805. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang J, Danke N, Roti M, Huston L, Greenbaum C, Pihoker C, James E, Kwok WW. CD4+ T cells from type 1 diabetic and healthy subjects exhibit different thresholds of activation to a naturally processed proinsulin epitope. J Autoimmun. 2008;31:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mallone R, Nepom GT. Targeting T lymphocytes for immune monitoring and intervention in autoimmune diabetes. Am J Ther. 2005;12:534–550. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000178772.54396.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nepom GT. Tetramer Analysis of Human Autoreactive CD4-Positive T Cells. Adv Immunol. 2005;88:51–71. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)88002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Novak EJ, Liu AW, Gebe JA, Falk BA, Nepom GT, Koelle DM, Kwok WW. Tetramer-guided epitope mapping: rapid identification and characterization of immunodominant CD4+ T cell epitopes from complex antigens. Journal of Immunology. 2001;166:6665–6670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novak EJ, Liu AW, Nepom GT, Kwok WW. MHC class II tetramers identify peptide-specific human CD4(+) T cells proliferating in response to influenza A antigen. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:R63–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI8476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novak EJ, Masewicz SA, Liu AW, Lernmark A, Kwok WW, Nepom GT. Activated human epitope-specific T cells identified by class II tetramers reside within a CD4high, proliferating subset. Int Immunol. 2001;13:799–806. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.6.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oling V, Marttila J, Ilonen J, Kwok WW, Nepom G, Knip M, Simell O, Reijonen H. GAD65- and proinsulin-specific CD4+ T-cells detected by MHC class II tetramers in peripheral blood of type 1 diabetes patients and at-risk subjects. J Autoimmun. 2005;25:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reichstetter S, Ettinger RA, Liu AW, Gebe JA, Nepom GT, Kwok WW. Distinct T cell interactions with HLA class II tetramers characterize a spectrum of TCR affinities in the human antigen-specific T cell response. J Immunol. 2000;165:6994–6998. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reijonen H, Mallone R, Heninger AK, Laughlin EM, Kochik SA, Falk BA, Kwok WW, Greenbaum C, Nepom GT. GAD65-specific CD4+ T-cells with high antigen avidity are prevalent in peripheral blood of patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53:1987–1994. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reijonen H, Novak E, Kochik S, Heninger A, Liu A, Kwok W, Nepom G. Detection of GAD65-specific T-cells by major histocompatibility complex class II tetramers in type 1 diabetic patients and at-risk subjects. Diabetes. 2002;51:1375–1382. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mallone R, Kochik SA, Laughlin EM, Gersuk VH, Reijonen H, Kwok WW, Nepom GT. Differential recognition and activation thresholds in human autoreactive GAD-specific T-cells. Diabetes. 2004;53:971–977. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Danke NA, Yang J, Greenbaum C, Kwok WW. Comparative study of GAD65-specific CD4+ T cells in healthy and type 1 diabetic subjects. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2005;25:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reddy J, Bettelli E, Nicholson L, Waldner H, Jang MH, Wucherpfennig KW, Kuchroo VK. Detection of autoreactive myelin proteolipid protein 139–151-specific T cells by using MHC II (IAs) tetramers. Journal of Immunology. 2003;170:870–877. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daniels MA, Devine L, Miller JD, Moser JM, Lukacher AE, Altman JD, Kavathas PB, Hogquist KA, Jameson SC. CD8 binding to MHC class I molecules is influenced by T cell maturation and glycosylation. Immunity. 2001;15:1051–1061. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jennes W, Kestens L, Nixon DF, Shacklett BL. Enhanced ELISPOT detection of antigen-specific T cell responses from cryopreserved specimens with addition of both IL-7 and IL-15--the Amplispot assay. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2002;270:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Standifer NE, Burwell EA, Gersuk VH, Greenbaum CJ, Nepom GT. Changes in autoreactive T cell avidity during type 1 diabetes development. Clinical Immunology. 2009;132:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vendrame F, Pileggi A, Laughlin E, Allende G, Martin-Pagola A, Molano RD, Diamantopoulos S, Standifer N, Geubtner K, Falk BA, Ichii H, Takahashi H, Snowhite I, Chen Z, Mendez A, Chen L, Sageshima J, Ruiz P, CG, Ricordi C, Reijonen H, Nepom GT, Burke GWr, Pugliese A. Recurrence of Type 1 Diabetes after Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation, despite Immunosuppression, Associated with Autoantibodies and Pathogenic Autoreactive CD4 T-cells. Diabetes. 2010 doi: 10.2337/db09-0498. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindert RB, Haase CG, Brehm U, Linington C, Wekerle H, Hohlfeld R. Multiple sclerosis: B- and T-cell responses to the extracellular domain of the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Brain. 1999;122:2089–2100. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.11.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bahbouhi B, Pettré S, Berthelot L, Garcia A, Elong Ngono A, Degauque N, Michel L, Wiertlewski S, Lefrère F, Meyniel C, Delcroix C, Brouard S, Laplaud DA, Soulillou JP. T cell recognition of self-antigen presenting cells by protein transfer assay reveals a high frequency of anti-myelin T cells in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2010;133:1622–1636. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bielekova B, Muraro PA, Golestaneh L, Pascal J, McFarland HF, Martin R. Preferential expansion of autoreactive T lymphocytes from the memory T-cell pool by IL-7. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;100:115–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chou YK, Bourdette DN, Barnes D, Finn TP, Murray S, Unsicker L, Robey I, Whitham RH, Buenafe AC, Allegretta M, Offner H, Vandenbark AA. IL-7 enhances Ag-specific human T cell response by increasing expression of IL-2R alpha and gamma chains. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;96:101–111. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.