Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to quantify the relation between elder self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilization in a community-dwelling population.

Methods

A prospective population-based study is conducted in a geographically-defined community in Chicago of community-dwelling older adults who participated in the Chicago Health and Aging Project. Of the 6,864 participants in the Chicago Health and Aging Project, 1,165 participants were reported to social services agency for suspected elder self-neglect. The primary predictor was elder self-neglect reported to social services agency. The outcome of interest was the annual rate of emergency department utilization obtained from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Poisson regression models were used to assess these longitudinal relationships.

Results

The average annual rate of emergency department visits for those without elder self-neglect was 0.6 (1.3) and for those with reported elder self-neglect was 1.9 (3.4). After adjusting for sociodemographics, socioeconomic variables, medical conditions, cognitive and physical function, elders who self-neglect had significantly higher rates of emergency department utilization (RR, 1.42, 95% CI, 1.29–1.58). Greater self-neglect severity (Mild: PE=0.27, SE=0.04, p<0.001; Moderate: PE=0.41, SE=0.03, p<0.001; Severe: PE=0.55, SE=0.09, p<0.001) was associated with increased rates of emergency department utilization, after considering the same confounders.

Conclusion

Elder self-neglect was associated with increased rates of emergency department utilization in this community population. Greater self-neglect severity was associated with a greater increase in the rate of emergency department utilization.

Keywords: elder self-neglect, emergency department utilization, population-based study

INTRODUCTION

Elder self-neglect is an important public health issue. Evidence suggests that reports of elder self-neglect to social services agencies are rising (1). In addition, elder self-neglect is associated with increased risk of mortality, and there is a gradient relationship between higher self-neglect severity and greater risk for mortality (2). Moreover, elder self-neglect has great relevance not only to health care professionals and social services agencies, but also to public health professionals, community organizations and other relevant disciplines. As our aging population increases, elder self-neglect will likely become an even more pervasive issue across all sociodemographic and socioeconomic strata.

The National Centers on Elder Abuse defines elder self-neglect as “…as the behavior of an elderly person that threatens his/her own health and safety. Self-neglect generally manifests itself in an older person as a refusal or failure to provide himself/herself with adequate food, water, clothing, shelter, personal hygiene, medication (when indicated), and safety precautions” (3). Despite recent advances in our knowledge of elder self-neglect, there remain gaps in our understanding in the health services utilization among those who self-neglect. Prior case reports suggest frequent health services utilization among those identified as self-neglectors (4;5). Recent epidemiological studies have provided conflicting results in health services utilization among self-neglectors after identification by the social services agency (6;7).

Emergency department utilization is a significant contributor to the rapidly increasing cost in our health care system. Recent biomedical and technological advances have significantly increased our ability to develop preventive services and disease prevention strategies. Older adults who self-neglect often manifest in behaviors that threaten their health and safety, which further predisposes their likelihood to have more frequent emergency department utilization. Despite contribution of recent work, we are not aware of any epidemiological study that has systematically examined the longitudinal association between elder self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilization in a community-dwelling population. Improved understanding of important factors that predict emergency department utilization could inform strategies for social services practice, public policy as well as clinical practice.

Furthermore, most prior research has categorized self-neglect dichotomously as “self-neglect” or “no self-neglect”. However, self-neglect, like many other geriatric syndromes, occurs along a continuum, rather than in two discrete categories. Our recent work suggests that improved understanding of the continuum of self-neglect is of critical importance, and that there is a gradient association between the continuum of elder self-neglect severity and adverse health outcomes (2;8;9). To-date, we are not aware of any epidemiological study that has quantified the relations between the continuum of elder self-neglect severity and emergency department utilization in the general population.

In this prospective population-based study, we aim to quantify: 1) the relationship between elder self-neglect and the rate of emergency department utilization within a prospective population-based cohort; and 2) the relationship between greater self-neglect severity and emergency department utilization in the same cohort. We hypothesized that older adults who self-neglect have increased rates of emergency department utilization, and that there is a gradient relationship between greater self-neglect severity and higher rate of emergency department utilization.

METHODS

Setting

Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP), a study begun in 1993, examines risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Its participants include residents of three adjacent neighborhoods on the south side of Chicago. More in depth details of the study design of CHAP have been previously published (10;11). Data collection occurred in cycles, each lasting three years, with each cycle ending as the succeeding cycle began. Each cycle consisted of in-person interviews in the participants’ homes.

Participants

In the current study, participants include those who were enrolled between 1993 and 2005 and had valid data on emergency department utilization history (N=6,864, 93.5%) obtained from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). There were total 476 participants did not have valid emergency department utilization data. From this cohort, we identified a subset of participants (N=1,165) who were reported to social services agencies for suspected elder self-neglect from 1993 to 2005. Suspected cases of elder self-neglect were reported by friends, neighbors, family, social workers, city workers, health care professionals, and others. The reports were usually triggered by concerns for the health and safety of the older adult in their home environment, which would initiate a number of different services to help the affected person. CHAP and social services data were matched using variables of date of birth, sex, race, home telephone number and exact home address. All CHAP participants received structured, standardized in-person interviews that included assessment of health history. Written informed consent was obtained, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Rush University Medical Center.

Reporting and Assessment of Self-Neglect

Elder self-neglect in this study was based on all suspected cases reported to social services agencies. When a case was reported, case worker performed a home assessment, which assessed the deficits in the domains of personal hygiene, household and environmental hazards, health needs and overall home safety concerns. The details of this measure has been previously described (9;12–18). In brief, there are a total of 15 items that rate the degree of unmet needs in multiple domains, and each item is scored from 0–3. The level of severity was rated by case workers based on their concerns for the client’s personal health and safety issues, with the maximum cumulative score of 45. Confirmed elder self-neglect in this study was defined as anyone with a score of 1 or greater (N=913). Elder self-neglect severity refers to the scores 1 to 45, with higher scores within this range indicating greater levels of elder self-neglect severity. Sometimes, caseworkers could not gain access to client’s home to make the assessment or a client may refuse the complete assessment. It is possible that these cases would denote as un-confirmed cases of self-neglect Available information from the social services agency internal report (19) showed that this measure was tested using the Kappa Statistic Algorithm (20), and all variables had inter-rater reliability coefficients great than 0.70. In addition, the internal consistencies of the items were high with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95(12). Both face and content validity were evaluated using qualitative data from case managers and agency administrators. In addition, predictive validity of the measure was assessed and shown to predict increased risk of premature mortality (2).

Emergency Department Utilization

Emergency department utilization records were abstracted from the Medicare Standard Analytic Files (SAFs) obtained from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS has approved the Study Protocol and Data Use Agreement with the CHAP study to obtain CMS data. CHAP study has successfully linked participants and their CMS claims data for the Medical Denominator Files and the SAF files which contains the record of emergency department utilization. For each participant, we have abstracted and summarized SAF files on their number of emergency department visits and amount of time between initial enrollment in the CHAP study to the identification of self-neglect as well as after the identification of self-neglect to the last available CMS data in December 2007.

Covariates

Demographic variables include age (in years), sex (men or women), race (self-reported: non-Hispanic black versus non-Hispanic white), and education (years of education completed). The parent CHAP study also collected self-reported medical conditions of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke, coronary artery disease, hip fracture, and cancer.

Physical function was assessed using the Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living (Katz ADL), which measured limitations in an individual’s ability to perform basic self-care tasks (21). Physical function was also assessed by direct performance testing, which provided a comprehensive objective and detailed assessment of certain abilities (22). Lower-extremity performance tests consisted of measures of tandem stand, timed walk, tandem walk, and ability to rise to a standing position from a chair. The tests requiring walking performance were quantified in terms of both the number of seconds to complete the task. Other tests were measured in terms of the number of trials completed within a specified time period. Most of these performance tests were used in the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (EPESE) project (22) and in other large-scale studies of disability. Summary measures of these above tests were created as physical performance test scores (range 0–15). Lower score indicate impairment in these above activities and tasks which are often needed for independent living and may contribute toward physical disability.

A battery of four cognitive function tests was administered: the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (23), immediate and delayed recall of brief stories in the East Boston Memory Test (24) and the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (25). To assess global cognitive function with minimal floor and ceiling artifacts, we constructed a summary measure for global cognition based on all 4 tests. Individual test scores were summarized by first transforming a person’s score on each individual test to a z-score, which was based on the mean and standard deviation of the distribution of the scores of all participants on that test, and then averaging z scores across tests to yield a composite score for global cognitive function. This procedure has the advantage of increasing power by reducing random variability present within tests, as well as reducing floor and ceiling effects of particular tests. In addition, it produces a composite score that is approximately normally distributed.

Analytic Approach

Descriptive characteristics were provided for the reported, confirmed, un-confirmed and un-reported elder self-neglect groups across the sociodemographic variables, socioeconomic variables, medical conditions, cognitive status and physical function status. Our independent variables of interest were reported self-neglect, confirmed self-neglect, and self-neglect severity. Our outcome of interest was annual rate of emergency department utilization, which was summarized for those with and without self-neglect. In addition, we calculated the annual rate of emergency department use for the different severities of elder self-neglect (Mild = score of 1–15; Moderate = score of 16–30; and Severe = score of 31–45). We used t-test or F-test to compare differences in the rate of emergency department utilizations between groups.

Poisson regression models were used to quantify the relation between elder self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilization. We used a series of models to consider these relationships, taking into consideration the potential confounders. In our core model (Model A), we included age, sex, race, education, and income to quantify the association of elder self-neglect and emergency department utilization outcomes. In addition, we added to the prior model common medical comorbidities of hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, hip fracture, cancer, and diabetes (Model B). Next we added to the prior model the levels of cognitive function (Model C). Finally, models were repeated controlling for additional physical function measures (Model D). We also repeated the prior models A-D to examine the association between confirmed elder self-neglect and non-reported groups (N=5,699) and rate of emergency department utilization.

In addition, we examined the association between elder self-neglect severity as a continuous variable and rate of emergency department utilization by repeating Models A-D. Moreover, we repeated these models for levels of self-neglect severity (Mild = 1–15; Moderate = 16–30; and Severe = 31–45) and rate of emergency department utilization. Lastly, we conducted analyses comparing those confirmed self-neglect to the un-confirmed cases of self-neglect adjusting for the same confounding factors. Rate Ratio (RR), 95% Confidence Interval (CI), Standardized-Parameter Estimates (PE), Standard Error (SE) and P values were reported for the regression models. Analyses were carried out using SAS®, Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

There were a total of 6,864 CHAP participants in this study and 1,165 participants were identified by social services agencies for suspected elder self-neglect from 1993 to 2005. The mean age of those with reported self-neglect was 78.3 years (standard deviation [SD] = 7.9 years), confirmed self-neglect was 76.9 (7.6), and those without self-neglect was 72.8 (6.7). Those with reported and confirmed self-neglect were more likely to be women, black older adults, and have lower levels of education and income (Table 1). In addition, those with reported and confirmed self-neglect compared to those without self-neglect were more likely to have coronary artery disease (22.3%, 23.1% vs. 13.1%), stroke (19.8%, 20.3% vs. 8.5%), cancer (23.8% vs. 18.7%), hypertension (69.1%, 69.2% vs. 47.6%) and diabetes (15.6%, 16.3% vs. 6.3%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Elders with Reported Self-Neglect and without Reported Self-Neglect in a Community-Dwelling Population

| Reported Self-Neglect (N=1165) | No Reported Self-Neglect (N=5699) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported (N=1165) | Confirmed (N=913) | Non-Confirmed (N=252) | ||

| Age, years, mean, (SD) | 78.3 (7.9) | 78.6 (8.1) | 76.9 (7.6) | 72.8 (6.7) |

| Women, number (%) | 765 (65.7) | 616 (67.5) | 149 (59.1) | 3278 (57.5) |

| Blacks, number (%) | 1005 (86.2) | 783 (85.7) | 222 (88.1) | 3194 (56.0) |

| Education, years, mean, (SD) | 11.3 (3.3) | 11.3 (3.3) | 11.2 (3.4) | 12.5 (3.6) |

| Income Categories, mean (SD) | 4.1 (2.1) | 4.0 (2.1) | 4.4 (2.2) | 5.4 (2.5) |

| Medical Conditions | ||||

| Coronary Artery Disease, number (%) | 259 (22.3) | 211 (23.1) | 48 (18.3) | 745 (13.1) |

| Stroke, number (%) | 231 (19.8) | 185 (20.3) | 46 (18.3) | 482 (8.5) |

| Cancer, number (%) | 277 (23.8) | 216 (23.7) | 61 (24.2) | 1063 (18.7) |

| Hypertension, number (%) | 803 (69.1) | 630 (69.2) | 173 (68.7) | 2695 (47.6) |

| Diabetes, number (%) | 182 (15.6) | 149 (16.3) | 33 (13.1) | 360 (6.3) |

| Hip Fracture, number (%) | 62 (5.3) | 51 (5.6) | 11 (4.4) | 188 (3.3) |

| Global Cognitive Function, mean (SD) | −0.24 (0.97) | −0.26 (0.97) | −0.13 (0.95) | 0.24 (0.79) |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 23.5 (6.9) | 23.3 (7.0) | 24.2 (6.4) | 26.4 (4.9) |

| Katz, mean (SD) | 1.0 (1.8) | 1.1 (1.8) | 0.7 (1.5) | 0.3 (1.0) |

| Physical Performance Testing, mean (SD) | 6.8 (4.5) | 6.5 (4.5) | 8.2 (4.3) | 10.7 (3.5) |

The annual rate of emergency department utilization for those no reported for self-neglect was 0.60 (1.33) and for those with reported elder self-neglect was 1.97 (3.36) (t-test, 23.06, p<0.001) (Table 2). Similar results were found for confirmed self-neglect. In addition, the study found a gradient increase in the levels of self-neglect severity and emergency department utilizations. The annual rate of emergency department utilization for mild self-neglect was 1.78 (3.04), for moderate self-neglect was 2.08 (3.29) and for severe self-neglect was 3.41 (5.72) (F-test, 5.66, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Elder Self-Neglect and Rate of Emergency Room Utilization

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | t-test | F-test | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Reported Self Neglect | 0.60 | 1.33 | 0.21 | 0.62 | |||

| Reported Self Neglect | 1.97 | 3.36 | 0.72 | 2.39 | 23.06 | <0.001 | |

| Un-Confirmed Self Neglect | 1.52 | 2.92 | 0.46 | 1.59 | 9.88 | <0.001 | |

| Confirmed Self Neglect | 2.09 | 3.46 | 0.77 | 2.67 | 23.41 | <0.001 | |

| Self Neglect Severity | |||||||

| Mild | 1.78 | 3.04 | 0.62 | 2.09 | |||

| Moderate | 2.08 | 3.29 | 0.92 | 2.73 | |||

| Severe | 3.41 | 5.72 | 1.08 | 4.03 | 5.66 | <0.001 | |

Elder Self-Neglect and Rate of Emergency Department Utilization

In the initial Poisson regression model adjusting for age, sex, race, education and income, we found that reported elder self-neglect independently predicted the increased rate of emergency department utilization (RR, 1.75, 95%CI, 1.68–1.83) (Table 3, Model A). After adding common chronic medical conditions of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cancer, thyroid disease, and myocardial infarction to the model (Model B), the association diminished slightly (RR, 1.52, 95%CI, 1.46–1.59). Next, we added cognitive function to the prior model and the association did not change (Model C). In the last model (Model D), after adjusting for physical function measures, reported elder self-neglect remained an independent predictor of increased rate of emergency department utilization (RR, 1.41, 95%CI, 1.34–1.48). For confirmed elder self-neglect, the associations were similar (Table 3)

Table 3.

Reported and Confirmed Elder Self-Neglect and the Risk of Emergency Room Utilization

| Reported Self-Neglect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Ratio (RR), 95% Confidence Intervals | ||||

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | |

| Age | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | 1.02 (1.01–1.02) |

| Men | 1.09 (1.06–1.13) | 1.11 (1.07–1.15) | 1.07 (1.03–1.10) | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) |

| Black | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) | 1.09 (1.06–1.14) | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.96 (0.92–0.99) |

| Education | 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) |

| Income | 0.93 (0.93–0.94) | 0.94 (0.93–0.94) | 0.94 (0.94–0.95) | 0.95 (0.94–0.96) |

| Medical Conditions | 1.29 (1.27–1.31) | 1.28 (1.26–1.30) | 1.25 (1.23–1.26) | |

| Cognitive Function | 0.79 (0.77–0.81) | 0.85 (0.83–0.87) | ||

| Physical Function | 0.95 (0.94–0.95) | |||

| ED Utilization for Reported Self-Neglect | 1.75 (1.68–1.83) + | 1.52 (1.46–1.59) + | 1.52 (1.45–1.59) + | 1.41 (1.34–1.48) + |

| Confirmed Elder Self-Neglect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Ratio (RR), 95% Confidence Intervals | ||||

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | |

| Age | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | 1.02 (1.02–1.02) |

| Men | 1.09 (1.06–1.13) | 1.10 (1.07–1.15) | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) |

| Black | 1.14 (1.09–1.18) | 1.11 (1.07–1.15) | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.97 (0.93–1.00) |

| Education | 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) |

| Income | 0.93 (0.93–0.94) | 0.94 (0.93–0.94) | 0.94 (0.94–0.95) | 0.95 (0.95–0.96) |

| Medical Conditions | 1.29 (1.28–1.32) | 1.29 (1.27–1.31) | 1.25 (1.23–1.27) | |

| Cognitive Function | 0.79 (0.77–0.81) | 0.85 (0.83–0.87) | ||

| Physical Function | 0.95 (0.94–1.51) | |||

| ED Utilization for Confirmed Self-Neglect | 1.81 (1.73–1.89) + | 1.58 (1.50–1.65) + | 1.57 (1.49–1.65) + | 1.43 (1.36–1.51) + |

Note:

p<0.001

Note: Comparison were between reported and confirmed self-neglect compared to the 5699 older adults in the non-reported group

Elder Self-Neglect Severity and Emergency Department Utilization

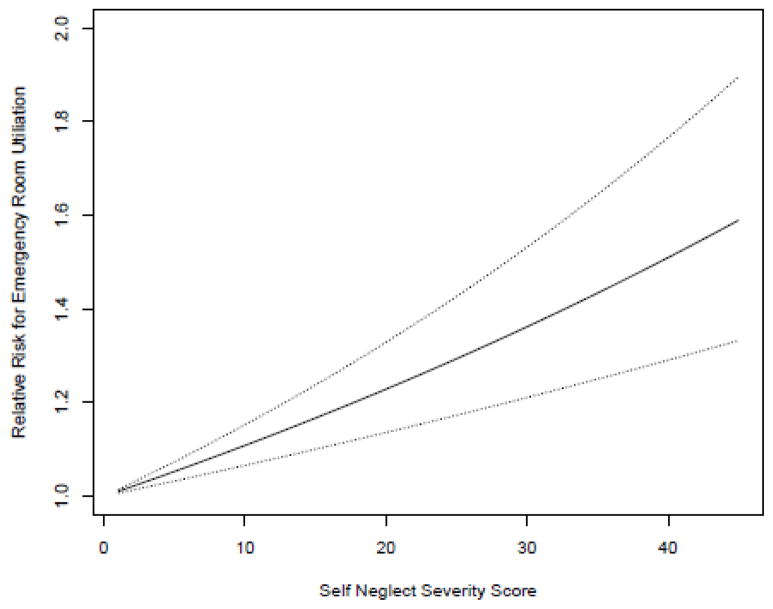

To quantify the relation between elder self-neglect severity from confirmed cases of self-neglect and emergency department utilization, an initial Poisson regression model adjusting for age, sex, race, education and income was created with emergency department utilization as the outcome (Model A). The coefficient representing the association of continuous self-neglect severity and emergency department utilization was 0.02 (SE, 0.01, p<0.001), suggesting a statistically significant gradient association between greater severities of elder self-neglect and increased rates of emergency department utilization. After adding chronic medical conditions of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cancer, thyroid disease, and coronary artery disease to the model (Model B), the association remained statistically significant. In the next model (Model C), addition of cognitive function did not change the prior associations. In the last model (Model D), after adding physical function measures to prior model, the coefficient changed minimally and remained statistically significant (PE = 0.01, SE, 0.01, p<0.001). Figure 1 graphically represents greater self-neglect severity and rate of emergency department utilization in the fully-adjusted model.

Figure 1. Elder Self-Neglect Severity and Rate of Emergency Department Utilization.

Figure 1 suggest that there is a gradient association between greater elder self-neglect severity score and rate for emergency department utilization

X-axis: represent the elder self-neglect severity score from 1 – 45

Y-axis: represent the increase in the rate of emergency department utilization

Note: The thin-dotted represent the 95% confidence interval for the association between greater self-neglect severity and risk ratio of emergency department utilization.

Moreover, we quantified the relation between categorically defined levels of self-neglect severity and rate of emergency department utilization (Table 4). In the core model (Model A), mild self-neglect (PE, 0.42, SE, 0.04, p<0.001), moderate self-neglect (PE, 0.68, SE, 0.03, p<0.001) and severe self-neglect (PE, 0.83, SE, 0.09, p<0.001) were all independent associated with the increased rate of emergency department utilization. In models B and C, addition of chronic medical conditions and cognitive function did not significantly change the associations between self-neglect severity and rate of emergency department utilization. In the fully-adjusted model (Model D), mild self-neglect (PE, 0.27, SE, 0.04, p<0.001), moderate self-neglect (PE, 0.41, SE, 0.03, p<0.001) and severe self-neglect (PE, 0.55, SE, 0.09, p<0.001) were all independent associated with the increased rate of emergency department utilization. Lastly, we conducted similar analyses within the reported self-neglect groups, comparing confirmed self-neglect with the non-confirmed self-neglect group. We found that confirmed self-neglect remain independently associated with increased rate of emergency department utilization (RR, 1.30, 95% CI, 1.19–1.43, p<0.001).

Table 4.

Elder Self-Neglect Severity and Emergency Room Utilization

| Models | Parameter Estimates | Standard Errors | Risk Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | A | 0.42 | 0.04 | 1.52 | 1.39–1.66 | <0.001 |

| B | 0.32 | 0.04 | 1.37 | 1.26–1.49 | <0.001 | |

| C | 0.32 | 0.04 | 1.37 | 1.26–1.50 | <0.001 | |

| D | 0.27 | 0.04 | 1.30 | 1.19–1.42 | <0.001 | |

| Moderate | A | 0.68 | 0.03 | 1.98 | 1.88–2.09 | <0.001 |

| B | 0.53 | 0.03 | 1.69 | 1.60–1.79 | <0.001 | |

| C | 0.52 | 0.03 | 1.67 | 1.58–1.77 | <0.001 | |

| D | 0.41 | 0.03 | 1.51 | 1.42–1.59 | <0.001 | |

| Severe | A | 0.83 | 0.09 | 2.28 | 1.89–2.76 | <0.001 |

| B | 0.61 | 0.09 | 1.84 | 1.53–2.22 | <0.001 | |

| C | 0.64 | 0.09 | 1.91 | 1.58–2.29 | <0.001 | |

| D | 0.55 | 0.09 | 1.73 | 1.42–2.09 | <0.001 |

Note: Self-Neglect Severity represents every one-point increase on the scale of 1–45 from the confirmed self-neglect group.

Models: A: Adjusted for age, sex, race, education and income

B: Adjusted for A + hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cancer, hip fracture, coronary artery disease

C: Adjusted for B + MMSE, East Boston Memory Test, East Boston Delayed Recall, and Symbol Digit Modality Test

D: Adjusted for C + physical function

DISCUSSION

In this prospective population-based study of 6,864 older adults from an urban geographically-defined community, we found that reported and confirmed elder self-neglect was independently associated with the increased risk of emergency department utilization. Moreover, higher level of elder self-neglect severity was associated with the greater risk of emergency department utilization.

Our findings expand the results of prior work of elder self-neglect and health services utilization. Prior study has matched the Connecticut Social Services Agency data to the Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Studies in the Elderly (EPESE) to identify the 120 cases of elder self-neglect. In this study (7), confirmed elder self-neglect was associated with increased risk of nursing home placement, after consideration of potential confounding factors. Other studies have indicated that older adults who have encounters with Adult Protective Services agencies have higher rate of health services utilizations (26;27). However, a recent retrospective case-control study of 131 self-neglect cases found no significant differences in health care utilizations compared the matched controls (6).

Our findings expand on the results of prior studies of elder self-neglect and health services utilization. First, our study is the largest population-based study to systematically examine the prospective association between elder self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilization; demonstrating a significant association between elder self-neglect increased rate of emergency department utilization. The study population is racially/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse and has been well characterized for more than 15 years, which contribute to the potential generalizability of our study findings.

Second, our study considered a wide range of potential confounders in the association between elder self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilization. Older adults who visit emergency department tend to be older, lower levels of socioeconomic status, more medical commorbidities, and have lower levels of cognitive and physical health. However, adjusting for these factors did not ameliorate the significant association between elder self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilization.

Third, the present study is the first population-based study able to examine the elder self-neglect as a continuum of severity with respect to rate of emergency department utilizations. Improved understanding of the potential gradient associations would contribute to our understanding to the potential causal association between elder self-neglect and health services utilization. This information could be useful in future prevention and intervention strategies for elders who self-neglect.

Lastly, emergency department utilization is enormously expensive and in-part responsible for the soaring health care cost. With recent biomedical and technological advances, it is critical for health care professionals, social services agencies and other relevant disciplines to identify older adults at risk for self-neglect and intervene before the deterioration occurs in extremes to warrant emergency department care. As we enter the era of health care reform, improved understanding of factors that increases emergency department utilization could also have significant implications for public policy and clinical practice.

The causal mechanisms between elder self-neglect and emergency department utilization remain incomplete. We considered a series of sociodemographic, socioeconomic characteristic, medical commorbidities, cognitive function, and physical function. However, adjustments for these factors did not change the relationship between elder self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilization. Metabolic abnormalities, nutritional deficiencies, infections, injuries or trauma may be other factors that could interact with self-neglecting behaviors which could account for the association between self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilization. However, we do have information on these factors to explore the mechanisms

Severity of chronic medical conditions (i.e., ejection fraction of patient with congestive heart failure, or Force Expiratory Volume of a patient with emphysema, etc) could another important factor in determining the causal mechanisms between self-neglect and emergency department utilization. In addition, it is conceivable that self-neglect could exacerbate the existing medical conditions (i.e., congestive heart failure or emphysema exacerbation, etc) which could predispose a higher rate of emergency department utilization. However, we do not have measures in our existing data to further elucidate these relations. Future studies are needed to explore the interactions of these variables with self-neglect with respect to emergency department utilization.

Our study also has a number of limitations. First, our study focused on the reporting of self-neglect as the primary predictor. Elder self-neglect was not ascertained uniformly for all members of the population, but only for participants referred to the social services agency because someone suspected problems. Self-neglect is under-reported, although the precise rate of under-reporting is unknown. At the same time, an un-confirmed case of self-neglect does not exclusively mean there is no evidence of self-neglect, as sometimes caseworker are refused entry or unable to complete assessments. Future studies are needed to uniformly collect self-neglect indicators in a representative population to rigorously examine these associations.

Second, ascertainment of emergency department utilization may not be complete. A limitation of using CMS data is selective under-detection of some services including use of Veterans Administration facilities and some managed care episodes. This under-detection of our outcomes of interest tends to underestimate the strength of association between self-neglect and emergency department utilization. Third, this study could not examine the relation between specific indicators/behaviors of elder self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilization. Improved understandings are needed to explore the adverse health outcomes associated with self-neglect phenotypes. Future studies are needed to elucidate the relation between specific phenotypes of elder self-neglect and emergency department utilizations.

Fourth, our study does not have available data on other relevant health services utilization measures (i.e., rate of outpatient physician visit, home health visit, hospitalization, duration of hospitalization, utilization of intensive care services. or nursing home placement, etc). This information could help to explain the causal mechanisms between elder self-neglect and emergency department utilization. Future studies of these relations deserve further exploration.

Fifth, there are likely to be additional factors that may account for the increased emergency department utilization (substance abuse, infection, injury/trauma, and etc). In addition, improved understanding of the interaction between elder self-neglect and the severities of medical conditions and other health-related factors could contribute toward the causal mechanisms between self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilization. More specifically, future studies are needed to elucidate the interactions among severity of medical conditions and its exacerbations, impairment in specific cognitive domains (episodic memory, executive function, etc), impairment in specific activities and instrumental activities in daily living and mobility, with respect to the relationship between self-neglect and health services utilizations. Regrettably, we do not have data to consider these additional confounders in our analyses, which may in-part account for the findings in this report. However, this study sets the foundation for future study of elder self-neglect to fully examine these issues.

Our findings have clinical implications for health care professionals in prevention, detection, and management of elder self-neglect. In the health care setting, health care professionals focus on preventive care and rigorous management of chronic medical conditions in order to avoid unnecessary utilization of emergency department. Health care professionals should consider screening for elder self-neglect among older patients who may have frequent encounters with emergency departments. In addition, health care professionals should be educated on the importance of screening elder self-neglect and could be integrated into the routine history taking for older patients in clinical settings. Vigilant monitoring of older adults who self-neglect could help clinicians to more closely monitor the patients and devise strategies to prevent unnecessary utilization of emergency department.

Moreover, our findings could have important implications for other disciplines that work with older adults with self-neglect. In addition to geriatricians, other relevant medical disciplines, nursing, social workers, and social services agencies who work with elders who self-neglect or who are at risk for self-neglect could be in unique positions to further monitor factors that may exacerbate the unnecessary use of the emergency department. In addition, it is important for all relevant disciplines to monitor the severity or the progression of self-neglecting behaviors in older adults. Early identification of milder forms of self-neglect and devising targeted prevention and intervention strategies could prevent deterioration of self-neglect into more severe forms, which in turn could potentially decrease the unnecessary utilization of emergency department services. Close monitoring and improved understanding of factors that may exacerbate self-neglect severity could also help clinicians leverage family members, social workers, health professionals, and public health and community organizations to create an interdisciplinary approach to comprehensively care for those with elder self-neglect.

Our findings also have direct implication for future research, by providing the first longitudinal evidence on elder self-neglect and rate of emergency department utilizations in a representative population. Future research is needed to explore temporal associations of targeted risk/protective factors associated with elder self-neglect in community-dwelling populations. Future studies are needed to explore the longitudinal association of elder self-neglect to the rate as well as the intensity of other forms of health services utilization. Also needed are studies examining the role of interventions to prevent elder self-neglect and/or reduce elder self-neglect severity with respect to health services utilization outcomes in community populations

Conclusion

We conclude that elder self-neglect is independently associated with an increased rate of emergency department utilization in a community-dwelling population. In addition, there is a gradient association between greater self-neglect severity and higher rates of emergency department utilization. Future longitudinal investigations are needed to explore the potential causal mechanisms between specific phenotypes of elder self-neglect and health services utilization. Future studies will also be necessary to adequately determine the specific causal mechanisms of the racial/ethnic and gender differences between elder self-neglect and health services utilizations in the general population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging grant (R01 AG11101), Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging (K23 AG030944), The Starr Foundation, American Federation for Aging Research, John A. Hartford Foundation and The Atlantic Philanthropies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Teaster PB. A response to abuse of vulnerable adults: The 2000 survey of state adult protective service. 2002 Jan 16; http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/ncearoot/Main_Site/pdf/research/apsreport030703.pdf.

- 2.Dong XinQi, Simon Melissa, Mendes de Leon Carlos, Fulmer Terry, Beck Todd, Hebert Liesi, Dyer Carmel, Paveza Gregory, Evans Denis. Elder Self-Neglect and Abuse and Mortality Risk in a Community-Dwelling Population. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009 Aug 5;302(5):517–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center on ELder Abuse Website. NCEA: the basics. 2006 Jun 20; http://elderabusecenter.org/pdf/research/apsreport030703.pdf.

- 4.Cybulska E, Rucinski J. Gross Self-Neglect in Old Age. Br J Hosp Med. 1986;36(1):21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roe PF. Self-Neglect. Age Ageing. 1977;6(3):192–4. doi: 10.1093/ageing/6.3.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franzini L, Dyer CB. Healthcare Costs and Utilization of Vulnerable Elderly People Reported to Adult Protective Services for Self-Neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Apr 1;56(4):667–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA. Adult Protective Service Use and Nursing Home Placement. Gerontologist. 2002;42(6):734–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong X, Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF, Evans DA. Self-Neglect and Cognitive Function Among Community-Dwelling Older Persons. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1002/gps.2420. In-Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong XinQi, Simon Melissa, Fulmer Terry, Mendes de Leon Carlos F, Rajan Bharat, Evans Denis A. Physical Function Decline and the Risk of Elder Self-Neglect in a Community-Dwelling Population. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(3):316–26. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bienias JL, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Design of the Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP) J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5(5):349–55. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans DA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Morris MC, Scherr PA, Hebert LE, Aggarwal N, Beckett LA, Joglekar R, Berry-Kravis E, Schneider J. Incidence of Alzheimer Disease in a Biracial Urban Community: Relation to Apolipoprotein E Allele Status. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(2):185–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong X, Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF, Evans DA. Self-Neglect and Cognitive Function Among Community-Dwelling Older Persons. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;25(8):798–806. doi: 10.1002/gps.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong X, Simon MA, Beck TT, Evans DA. A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study of Elder Self Neglect and Psychological, Health, and Social Factors in a Biracial Community. Aging and Mental Health. 2010;14(1):74–84. doi: 10.1080/13607860903421037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong X, Wilson RS, Simon MA, Rajan Bharat, Evans DA. Cognitive Decline and Risk of Elder Self-Neglect: The Findings From the Chicago Health and Aging Project. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2010;58(12):2292–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong X, Simon MA, Wilson RS, Beck TT, McKinnell K, Evans DA. Association of Personality Traits With Elder Self-Neglect in a Community-Dwelling Population. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182006a53. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong X, Simon MA, Evans DA. Characteristics of Elder Self-Neglect in a Biracial Population: Findings From a Population-Based Cohort. Gerontology. 2010;56(3):325–34. doi: 10.1159/000243164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong X, Beck TT, Evans DA. A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study of Self-Neglect and Psychosocial Factors in a Biracial Community. Aging and Mental Health. 2010;14(1):74–84. doi: 10.1080/13607860903421037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong XinQi, Mendes de Leon Carlos F, Evans Denis A. Is Greater Self-Neglect Severity Associated With Lower Levels of Physical Function? Journal of Aging and Health. 2009 Jun 1;21(4):596–610. doi: 10.1177/0898264309333323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Illinois Department on Aging. Determination of Need Revision Final Report. I. Illinois Department on Aging; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleiss JL. Measuring Nominal Scale Agreement Among Many Raters. Psychological Bulletin. 1971;76:378–82. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz S, Akpom CA. A Measure of Primary Sociobiological Functions. Int J Health Serv. 1976;6(3):493–508. doi: 10.2190/UURL-2RYU-WRYD-EY3K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB. A Short Physical Performance Battery Assessing Lower Extremity Function: Association With Self-Reported Disability and Prediction of Mortality and Nursing Home Admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert M, Smith LA, Scherr PA, Taylor JO, Evans DA, Funkenstein HH. Use of Brief Cognitive Tests to Identify Individuals in the Community With Clinically Diagnosed Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Neurosci. 1991;57(3–4):167–78. doi: 10.3109/00207459109150691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test Manual-RevisedLos Angeles: Western Psychological. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schonfeld Lawrence, Larsen Rebecca G, Stiles Paul G. Behavioral Health Services Utilization Among Older Adults Identified Within a State Abuse Hotline Database. The Gerontologist. 2006 Apr 1;46(2):193–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Hurst L, Kossack A, Siegal A, Tinetti ME. ED Use by Older Victims of Family Violence. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30(4):448–54. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]