Abstract

Purpose

Increased expression of FGFR-4 and its ligands have been linked to lethal prostate cancer (PCa). Furthermore, a germline polymorphism in the FGFR-4 gene, resulting in arginine at codon 388 (Arg388) instead of glycine (Gly388), is associated with aggressive disease. The FGFR-4 Arg388 variant results in increased receptor stability, sustained receptor activation and increased motility and invasion compared to Gly388. However, the impact of sustained signaling on cellular signal transduction pathways is unknown.

Experimental Design

Expression microarray analysis of immortalized prostatic epithelial cells lines expressing FGFR-4 Arg388 or Gly388 was used to establish a gene signature associated with FGFR-4 Arg388 expression. Transient transfection of reporters and inhibitors were used to establish the pathways activated by FGFR-4 Arg388 expression. The impact of pathway knockdown in vitro and in an orthotopic model was assessed using inhibitors and/or shRNA.

Results

Expression of the FGFR-4 Arg388 protein leads to increased activity of the extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) pathway, increased activity of serum response factor (SRF) and AP1 and transcription of multiple genes which are correlated with aggressive clinical behavior in PCa. Increased expression of SRF is associated with biochemical recurrence in men undergoing radical prostatectomy. Consistent with these observations, knockdown of FGFR-4 Arg388 in PCa cells decreases proliferation and invasion in vitro and primary tumor growth and metastasis in vivo.

Conclusions

These studies define a signal transduction pathway downstream of FGFR-4 Arg388 that acts via ERK and SRF to promote prostate cancer progression.

Keywords: prostate cancer, fibroblast growth factor receptor, serum response factor, MAP kinase, invasion

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common visceral malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men in the United States. An extensive body of evidence links fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and FGF receptors (FGFRs) to PCa initiation and progression (1). FGFs are a family of more than 20 different polypeptide ligands involved in a variety of biological and pathological processes. FGFRs are transmembrane proteins tyrosine kinase receptors and there are four distinct FGF receptors (FGFR 1–4) which have variable affinities for the different FGFs. Upon binding to FGFs activation of various downstream signaling pathways including phospholipase c-γ (PLC-γ), PI3K/Akt, extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) and STATs are activated (1–2). A wide range of cellular phenotypic responses have been observed following activation of FGFRs which can be receptor-type dependent, although the basis of these differences is not well understood.

There is strong evidence for the involvement of FGFR-4 in PCa initiation and progression. There is increased expression of several FGFs that preferentially bind to FGFR-4 in PCa and in many cases this expression is correlated with poor clinical outcome (1, 3–6). There is increased expression of FGFR-4 in PCa (7) by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and strong expression of FGFR-4 is significantly associated with poor clinical outcome (6, 8). Furthermore, our group has shown that a germline polymorphism in the FGFR-4 gene, resulting in expression of FGFR-4 containing arginine at codon 388 (Arg388), instead of a more common glycine (Gly388), is associated with PCa initiation and progression (7). The Arg388 polymorphism is quite frequent in the Caucasian population since approximately 45% of individuals are hetero- or homozygous for this allele. A recent meta-analysis of multiple studies has confirmed the association of prostate cancer risk and the presence of the FGFR-4 Arg388 polymorphism (9). Correlation of the presence of the Arg388 allele with poor prognosis has been observed in a wide variety of malignancies (10–15). Recent genetic studies using a knock-in mouse with the analogous polymorphism have confirmed that this polymorphism can accelerate breast cancer progression in mouse models (16).

Consistent with these clinical observations, expression of the FGFR-4 Arg388 in immortalized prostate epithelial cells results in increased cell motility and invasion (7). It has been shown that achondroplasia is caused by a similar mutation in FGFR-3 (Gly380 to Arg380) and increased FGFR-3 signaling due to this mutation inhibits proliferation in chondrocytes (17–18). This mutation leads to decreased receptor turnover due to increased receptor recycling and decreased targeting of receptors to lysosomes (17–18). We have shown that the FGFR-4 Arg388 variant also shows increased receptor stability and sustained receptor activation following ligand binding when compared to the Gly388 variant (19). However, the impact of this sustained signaling on cellular signal transduction pathways is unknown. We therefore analyzed the effect of FGFR-4 Arg388 expression on signal transduction in prostatic epithelial cells. We have found that expression of the FGFR-4 Arg388 allele leads to increased activity of the extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) pathway, increased activity of serum response factor and AP1 and transcription of multiple genes which are correlated with aggressive clinical behavior in prostate cancer. Consistent with these observations, knockdown of FGFR-4 Arg388 in PCa cells decreases proliferation and invasion in vitro and primary tumor growth and metastasis in vivo.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Cell lines and reagents

PNT1a, PC3 and DU145 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). U0126, U73122, and SP600125 were from EMD Chemicals Inc.

Generation of stable cell lines

PNT1a FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 cell lines have been described previously (19) and DU145 overexpressing FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 cells were generated in a similar manner. There was no significant difference in expression of FGFR-4 in the DU145 cell lines by quantitative RT-PCR carried out as described previously (19). The shFGFR-4 lentivirus and establishment of stable cell lines were as described previously (19). A human GIPZ lentiviral shRNAmir individual clone (V2LHS_153469) targeting SRF was obtained from Open Biosystems and used to obtain stable cell lines.

Expression microarray analysis

The expression microarray labeling, hybridization and scanning were performed as described previously (20). Expression arrays were processed and loess-normalized using BioConductor. Array data has been deposited in the public Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) data base, accession GSE20906. To define differentially expressed genes between FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 samples, we used a criterion of a minimum fold change of 1.4 between each Arg388 sample and each Gly388 sample. Java TreeView (21) represented expression patterns as color maps. To score each of the Glinsky et al. (22) prostate tumors for similarity to our Arg388 gene signature, we derived a “t-score” for each Glinsky tumor in relation to the Arg388 signature as previously described (23). The mapping of transcripts or genes between array datasets was made on the Entrez Gene identifier; where multiple human array probe sets referenced the same gene, the probe set with the highest variation represented the gene.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

RT-PCR assays were performed as described previously (19). Primers used are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The PCR conditions were 30-s denaturation, 30-s annealing at the 60°, and 30-s extension at 72°C for 40 cycles. The relative copy number of transcript for each gene was normalized by transcript level of the β-actin gene. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate.

Transfection and luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter assays were carried out as previously described (24). The SRE, AP1 and NFAT reporter constructs were obtained from Stratagene (Pathdetect). The androgen responsive ARE reporter construct was obtained from Dr Carolyn Smith, Baylor College of Medicine, and has been described previously (25). The data presented are the mean of three individually transfected wells and the experiments are performed at least three times.

Matrigel® invasion assay

The Matrigel invasion assays were performed in triplicate as described previously except that the cells were seeded in RP1640 medium supplemented with 0.1% FBS (PNT1a) or 0.5% FBS (DU145) and 50 ng/ml FGF2 (7). For PC3 cells, 5% FBS without added FGF was used. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed as described previously (26). Antigen retrieval was performed using Tris HCl, pH 9.0. Arrays were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with anti-SRF antibody (sc-335, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:500) and staining developed using an Envision+ Kit (Dako). The anti-SRF antibody has been previously validated for IHC (27). Sections incubated with secondary antibody only showed no staining.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer containing Tris 50 mM, NaCl 150 mM, Triton X-100 1%, SDS 0.1%, deoxycholate 0.5%, sodium orthovanadate 2 mM, sodium pyrophosphate 1mM, NaF 50mM, EDTA 5 mM, PMSF 1 mM and 1x protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and clarified by centrifugation. Protein concentration of the lysates was determined using BCA protein assay kit (Thermo). The extracted proteins (25μg) were loaded on 10% SDS PAGE gels. Proteins were transferred onto Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Invitrogen), and the membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk powder in TBS-Tween 20 (0.1%) for 1h at room temperature. The antibodies from Cell Signaling, e.g., Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (p-Erk1/2) rabbit mAb (#4370), p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) rabbit mAb (#4695), and β-Tubulin(#2128) rabbit mAb were used at 1:1000 dilution. A mouse anti-V5 mAb (Invitrogen R960–25) was used at 1:5000. After incubation with primary antibodies for overnight at 4°C, horseradish peroxidase labeled secondary antibodies were then applied to the membranes for 1 h at room temperature. Signals were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection reagents (Thermo).

PC3 orthotopic mouse model

PC3 prostate cancer cells expressing a shRNA targeting FGFR-4 or scramble shRNA controls, established as described previously (19), were injected orthotopically into the prostates of eight- to ten-week-old nude mice using 1×106 cells in a volume of 20 μL. Mice were sacrificed at 7 weeks after injection and the primary tumors were harvested and weighed. A full necropsy including pelvic and abdominal lymph nodes was performed to identify metastasis. All primary tumors and metastases were confirmed by pathological examination by a pathologist (MI). All procedures were approved by the Baylor College of Medicine IACUC.

RESULTS

Expression of FGFR4 Arg388 induces a gene expression signature associated with aggressive disease

PNT1a are immortalized prostatic epithelial cells and we have shown that in PNT1a cells expressing exogenous FGFR4 Arg388 or Gly388 under the control of the EF1 promoter almost all FGFR signaling can be attributed to the transfected receptor, and the two FGFR-4 isoforms are expressed at equivalent levels in the two cell lines (19). We have also shown that serum contains FGF ligands capable of activating FGFR-4 (19) and in such conditions the Arg388 expressing PNT1a cells display increased invasiveness and motility compared to Gly388 expressing cells (7, 19). To further understand the underlying molecular mechanisms of increased cell motility and invasiveness in Arg388 expressing cells, microarray studies of biological duplicates were performed on FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 expressing PNT1a cells using Agilent 44k whole genome expression microarrays to identify the effector genes that may be responsible for phenotypic differences between the two variants. A total of 229 genes that were upregulated by at least 1.4 fold in FGFR-4 Arg388 cells compared to Gly388 cells and 212 genes that showed a similar downregulation (Figure 1A). Selected genes that were upregulated or down-regulated are shown and the full gene list is shown in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. Of note was the upregulation of cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-1α and CXCL1. Other genes included MMP1, which is associated with invasion; lysyl oxidase (LOX) and several collagen genes, which indicate a more mesenchymal phenotype; transcription factors (ZNF19, ZNF22) and genes involved in signal transduction (GRB1, CRKL and RelA). IL-18, which is associated with anti-tumor immunity (28) was downregulated as were several genes known to be downregulated during the transition from prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cancer (ITGB2 (29), CD40(30)). We confirmed the upregulation of 7 genes in PNT1a cells expressing Arg388 versus Gly388 cells using quantitative RT-PCR (see below). Thus the expression microarrays accurately reflect changes in gene expression induced by FGFR-4 Arg388 and a number of genes with altered expression have relevant biological activities.

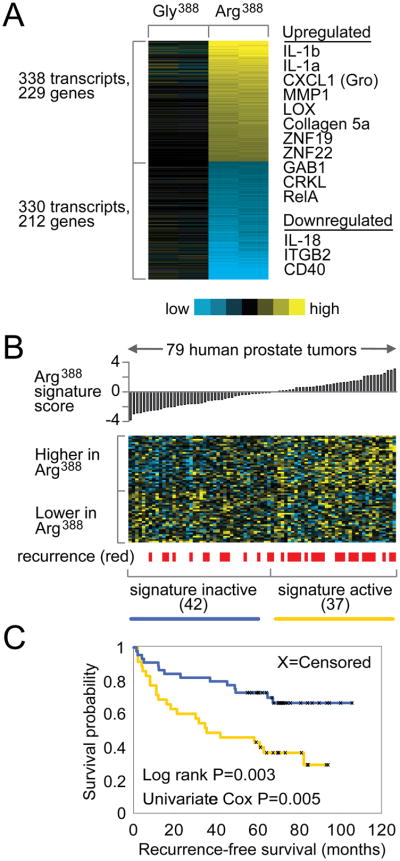

Figure 1. Gene transcription signature of FGFR-4 Arg388 versus FGFR-4 Gly388 cells.

(A) Heat map of genes differentially expressed between FGFR-4 Arg388 and FGFR-4 Gly388 PNT1a cells (yellow: high expression; blue: low expression). (B) The expression patterns of the Arg388 gene signature in a panel of 79 PCa tumors from Glinsky et al. Tumors are ordered by the “Arg388 signature t-score” which measures the similarity of the tumor profile with the Arg388 versus Gly388 patterns. (C) Kaplan-Meier analysis comparing the differences in risk of disease relapse between human tumors showing activation (yellow line, t-score>0) of the Arg388 signature and tumors showing deactivation (blue line, t-score<0) of the signature. Log rank test evaluates whether there are significant differences between the two arms. Univariate Cox test evaluates the association of the Arg388 signature t-score with patient outcome, treating the coefficient as a continuous variable.

Given the association of the FGFR-4 Arg388 isoform with aggressive disease we compared our FGFR-4 Arg388 gene signature with the gene expression data of Glinsky et al (22) and examined whether the FGFR-4 Arg388 signature was associated with aggressive clinical behavior. As can be seen in Figures 1B and 1C, patients with the FGFR-4 Arg388 gene signature were significantly more likely to develop recurrence following radical prostatectomy than men with cancers without the Arg388 gene signature (log rank test, p=0.003).

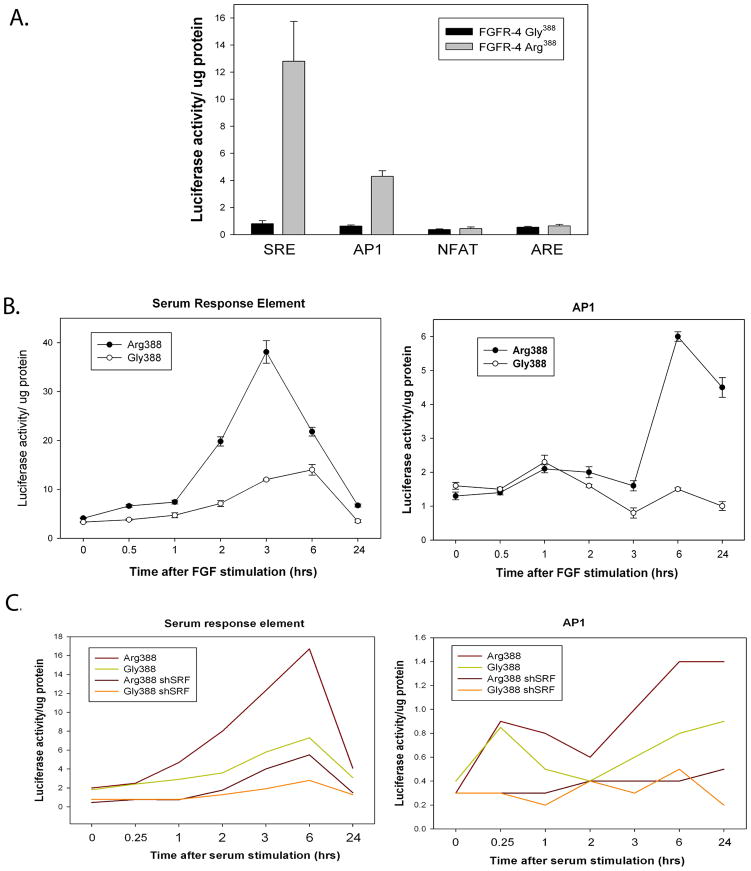

Enhanced induction of serum response factor and AP1 activities by the FGFR4 Arg388 allele

To characterize the signaling pathways that account of the observed differences in phenotype and gene expression changes between FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 variants, we transfected a set of luciferase promoter reporter constructs into PNT1a cells expressing either the Arg388 or Gly388 FGFR-4 allele. We found that luciferase reporter constructs containing serum response elements (SRE), which bind serum response factor (SRF), showed a 13-fold increase in luciferase expression in Arg388 expressing PNT1a cells when compared to the Gly388 expressing cells (Fig 2A). A 7-fold increase was seen for reporter constructs with AP1 binding sites in the promoter. There were no significant differences in NFAT or ARE promoter activities (Fig 2A). It should be noted that PNT1a cells, like all non-transformed prostatic epithelial cells in culture, do not express androgen receptor (AR) so the ARE is a negative control. To further characterize these differences we carried out a detailed time course study of these cell lines in both serum free medium with FGF2 as the only growth factor and serum containing medium. Cells were plated, and the next day transfected with SRE or AP1 reporter constructs and then placed in serum-free media without FGF2 overnight. Cells were then stimulated with FGF2 and luciferase activity measured in cell extracts collected at intervals over 24 hours. FGF2 was chosen as the ligand since it stimulates FGFR-4 and has repeatedly been shown to be elevated in prostate cancer (31). SRE expression constructs showed an almost 10-fold increase in luciferase activity in FGFR-4 Arg388 expressing cells, peaking at 3 hours after FGF2 addition (Fig 2B). The AP1 reporter constructs exhibited an approximately 4-fold increase in activity (Fig 2B) and had a more sustained increase in activity. The Gly388 expressing cells showed a more modest (4-fold) induction of luciferase activity with SRE constructs and no significant induction with the AP1 constructs. Similar experiments were carried out using serum stimulation and including PNT1a Arg388 and Gly388 cells lines in which SRF was knocked down using shRNA. As shown in Figure 2C, the FGFR-4 Arg388 expressing cells showed an 8-fold increase SRE promoter activity by 6 hours as compared to less than 3-fold for the Gly388 cells in response to serum stimulation. This response was significantly decreased in shSRF expressing cells. The AP1 reporter construct showed a 3.5-fold increase the Arg388 expressing cells by 6 hrs after serum stimulation and the Gly388 expressing cells showed a 2-fold increase. This response was completely abolished in shSRF expressing cell lines, indicating that the induction of AP1 is downstream of SRF. Interestingly, the Arg388 and Gly388 expressing cell lines both displayed a transient 2-fold increase in AP1 reporter activity at 15 minutes after stimulation in serum that was not seen in FGF2 serum free medium. This transient response was not seen in the shSRF expressing cells and is presumably due to other growth factors in serum that activate SRF via a more transient signal. Thus both FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 activate SRF and AP1 signaling but the response in FGFR-4 Arg388 expressing cells is more robust.

Figure 2. FGFR-4 Arg388 activates SRE and AP1 transcription.

(A) PNT1a cells expressing FGFR-4 Arg388 or Gly388 were transfected with luciferase reporter constructs under the control of SRE, AP1, NFAT and ARE regulated promoters. 24 hours after transfection protein lysates were prepared and normalized luciferase activity determined. Mean +/− standard deviation (SD) of triplicates. (B) The cell lines used above were plated, and the next day transfected with SRE or AP1 reporter constructs and then placed in serum-free media without FGF2 overnight. Cells were then stimulated with FGF2 and normalized luciferase activity measured in cell extracts collected at intervals over 24 hours. (C) PNT1 a cells expressing Arg388 or Gly388 with stable expression of shRNA knocking down SRF or vector controls were transfected and placed in serum free medium as above. FBS was added (final 10%) after 24 hrs and normalized luciferase activity measured in cell extracts collected at intervals over 24 hours.

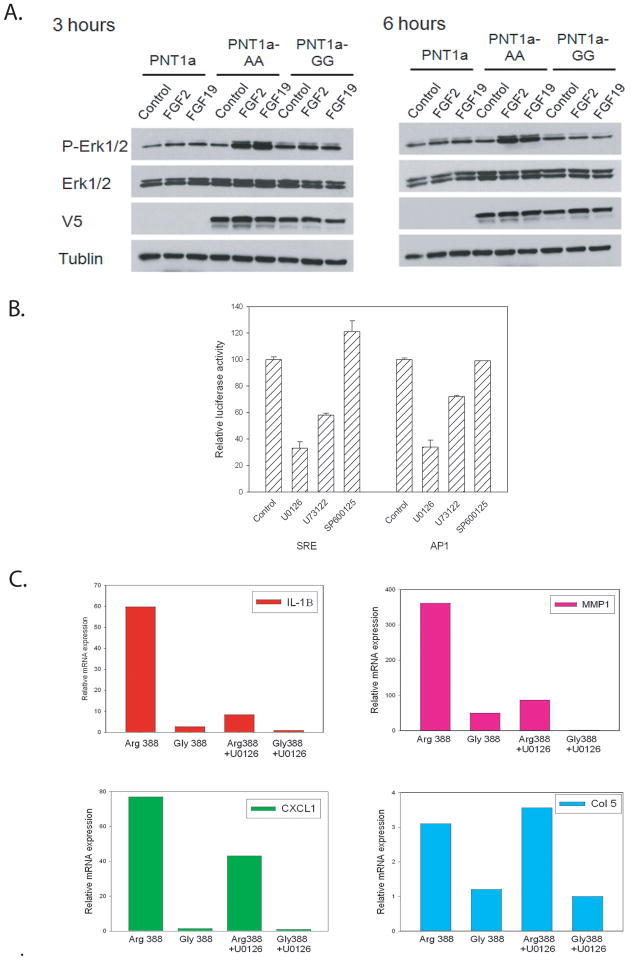

FGFR-4 Arg388 activates ERK signaling

It is known that SRF and AP1 transcription can be activated by ERK signaling in response to growth factor stimulation (32). To determine if FGFR-4 Arg388 increases ERK signaling when compared to Gly388 we serum starved parental PNT1a cells and PNT1a expressing FGFR-4 Arg388 or Gly388 overnight and stimulated them with FGF2 or FGF19 or vehicle only. FGF19 activates FGFR-4 in the presence of Klotho co-receptors (33) and PNT1a express α-Klotho (unpublished data). FGF2 binds multiple FGF receptors with high affinity including FGFR-4. Protein lysates were collected at 3 or 6 hours and analyzed by Western blotting. As can be seen in Fig 3A, at 3 hours the FGFR-4 Arg388 expressing cells had significantly increased ERK phosphorylation compared to FGFR-4 Gly388 expressing cells and both were higher than PNT1a. At 6 hours, the FGFR-4 Arg388 expressing cells maintained high levels of ERK phosphorylation, consistent with the sustained FGFR-4 phosphorylation after FGF stimulation of this isoform as we have demonstrated previously (19). The FGFR-4 Gly388 cells had low levels of ERK phosphorylation at this time point, similar to control PNT1a. Thus FGFR-4 Arg388 cells have higher and more sustained ERK phosphorylation than Gly388 expressing cells.

Figure 3. ERK regulation of the FGFR-4 Arg388 enhanced transcription.

(A) FGFR-4 Arg388 (AA) and Gly388 (GG) expressing PNT1a or control PNT1a cells were serum starved overnight were stimulated with FGF2 (25 ng/ml) or FGF19 (50ng/mL) for 3 h and 6 h. Cell lysates were prepared and Western blot analyses were conducted using antibodies against phospho-p44/42 ERK (p-Erk1/2), p44/42 ERK (Erk1/2), V5-epitope, and β-tubulin. (B) FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 expressing PNT1a cells were treated with U0126 (10 μM), U73122 (10 μM) and SP600125 (10 μM) or vehicle only for 24 hrs and transfected with SRE or AP1 reporter plasmids and normalized luciferase activity determined at 24 hrs. Mean +/− SD of triplicates. (C) FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 expressing PNT1a were treated with U0126 (10 μM) for 24 hrs or with vehicle only, RNAs collected and expression of IL-1β, MMP1, CXCL1 and Collagen 5a determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Values are relative to the lowest expressing sample (Gly388 treated with U0126 in all cases)

To determine whether the increased luciferase activity of SRE and AP1 reporter constructs in FGFR-4 Arg388 expressing PNT1a cells was due to enhanced ERK activation, we carried out inhibitor studies with U0126, an inhibitor of MKK, which activates ERK signaling. As shown in Figure 3B, U0126 inhibited luciferase activity driven by either of these promoters by approximately 70%. U73122, a phospholipase-C γ (PLC-γ) inhibitor decreased activity of the SRE and AP1 reporters by 40% and 25% respectively. It has been shown previously that PLC-γ can enhance ERK kinase signaling by FGF receptors (34). The JNK inhibitor SP600125 did not inhibit reporter activity from either of these promoters. These findings indicate that FGFR-4 Arg388 activates SRF and AP1 signaling through increased ERK signaling.

To determine the extent to which ERK can activate the gene expression changes in the FGFR-4 Arg388 cells we examined expression of a 7 genes that were identified as being upregulated by FGFR-4 Arg388 by microarrays using quantitative RT-PCR with RNAs from Arg388 and Gly388 PNT1a cells treated with U0126 and control (vehicle only). The results of 4 such studies are shown in Figure 3C. All genes showed increased expression in Arg388 cells relative to Gly388 cells in the vehicle controls. For 6 of 7 genes tested U0126 significantly decreased gene expression from 40–90% in Arg388 cells, with variable decreases in Gly388 cells (0 to >90%). One gene (collagen 5a) showed no decrease in response to U0126 although it was increased in the Arg388 expressing cells. Thus the majority of genes upregulated in Arg388 PNT1a cells are significantly regulated by ERK activity but some are upregulated by other pathways.

We also compared expression in FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 cells to control PNT1a cells for four genes. In all cases gene expression in the FGFR-4 Arg388 PNT1a cells was statistically significantly higher than PNT1a cells while 3 of 4 genes tested were significantly higher in the FGFR-4 Gly388 cells (p<0.01, t-test) than control PNT1a (Supplementary Fig 1). Interestingly the only gene not higher in the FGFR-4 Gly388 cells was collagen 5a, which is not ERK regulated, and collagen 5a expression was actually lower (p=0.02, t test) in the FGFR-4 Gly388 cells compared to control PNT1a, suggesting the possibility that FGFR-4 Gly388 may negatively regulate activity of a non-ERK pathway. Our data indicates that FGFR-4 Gly388 increases ERK activity, but to a lesser extent than Arg388.

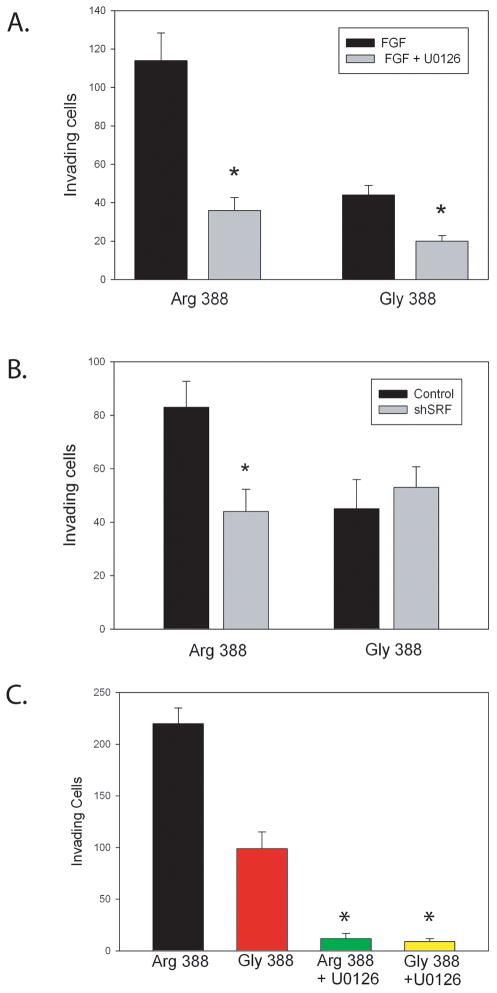

ERK enhances invasion via upregulation of SRF activity

We have shown that FGFR-4 Arg388 enhances tumor invasion and motility and that it can activate a series gene expression changes that are associated with aggressive behavior in PCa by activation of ERK and SRF activity. We therefore examined whether inhibition of ERK with U0126 could inhibit invasion in FGFR-4 Arg388 expressing PNT1a cells (Fig 4A). U0126 markedly inhibited invasion of Arg388 expressing cells and to a lesser extent Gly388 expressing PNT1a cells. To determine if this inhibition involves SRF we compared invasion of Arg388 and Gly388 PNT1a expressing a shRNA targeting SRF. The shSRF expressing Arg388 cells were markedly less invasive and were similar to the Gly388 cells (Fig 4B). To confirm these results in a second system we expressed FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 at equal levels (by quantitative RT-PCR) in DU145 PCa cells and evaluated invasiveness in FGF defined medium with or without U0126. As can be seen in Figure 4C, the FGFR-4 Arg388 expressing cells were more highly invasive than the Gly388 expressing cells and U0126 markedly inhibited invasion for both cell lines.

Figure 4. ERK and SRF signaling enhance invasion of prostate and prostate cancer cells expressing FGFR-4 Arg388.

(A) PNT1a cells expressing FGFR-4 Arg388 or Gly388 were plated in the upper chamber of Matrigel Transwell chambers in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 0.1% serum and 50 ng/ml FGF2 with or without U0126 (10 μM) and incubated for 48 hours. Cells invading through the membrane were counted. (B) PNT1 a cells expressing Arg388 or Gly388 with or without a shRNA knocking down SRF were plated as above. After 48 hours cells invading through the membrane were counted. (C) DU145 cells expressing FGFR-4 Arg388 or Gly388 were plated in Transwell chambers in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 0.5% serum and 50 ng/ml FGF2 with or without U0126 (10 μM) and incubated for 36 hours. Cells invading through the membrane were counted. Means of triplicates +/− SD are shown. Significant differences by t-test between treated or shSRF and controls are indicated by asterisks.

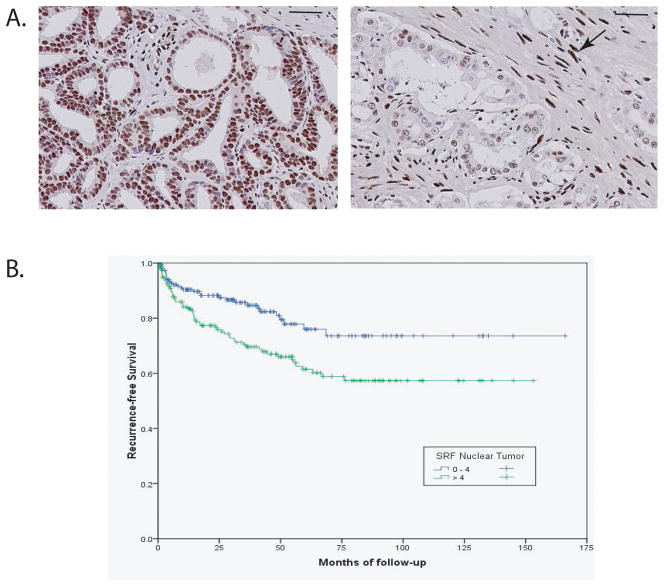

SRF expression in prostate cancer tissues

The data above implicates SRF as a key target of FGFR-4 Arg388. To confirm that SRF is expressed in PCa and determine the clinical relevance of such expression, we analyzed the expression of SRF by IHC using a large PCa tissue microarray with more than 400 PCas from radical prostatectomies. Expression was quantitated as described previously (26, 35) based on a multiplicative index of the average staining intensity (0–3) and extent of staining (1–3) in the cores yielding a 10 point staining index (0–9). Examples of strong (index 9) and weak tumor (index 2) staining are shown in Figure 5A. Staining was exclusively nuclear. Overall, 80% of cancers had detectable SRF expression. Almost half (48%) of all men had moderate to strong expression of SRF (index >4). Strong staining of stromal nuclei was noted (Fig 5A). This is consistent with ongoing growth factor stimulation of stromal cells by growth factors including FGFs. Expression of SRF was significantly correlated with both extracapsular extension (0.138, p=0.007) and Gleason score (0.218, p<.0001). Consistent with this, men with cancers with moderate to strong SRF staining index (>4) had a significantly increased risk of biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy (log rank 0.004; Fig 5B). In addition, SRF expression was significantly correlated with proliferation (35) as assessed by Ki67 IHC (correlation coefficient 0.156, p=0.03) and negatively correlated with apoptosis (36), as assessed by TUNEL staining (−0.183, p=.016). There was also a strong correlation with the percentage reactive stroma in the tumor (0.221, p<.0001). Our group has previously shown that cancers with increased reactive stroma are more aggressive than those with only minimal stromal response (37). Finally, we also found a strong correlation with perineural tumor diameter (0.3, p<.0001). Maru et al (38) has shown that large diameter perineural invasion is a very strong predictor of biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy. Thus SRF is expressed at moderate to high levels in half of PCas and higher SRF expression is associated with poor outcome following radical prostatectomy, perhaps in part by altering interactions between cancer cells and their microenvironment.

Figure 5. Serum response factor is expressed in prostate cancer and increased expression is associated with biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy.

Tissue microarrays containing prostate cancers (n=387) were analyzed by immunohistochemistry with anti-SRF antibody and staining quantitated. (A) Examples of SRF expression in prostate cancer. Left: strong uniform staining, index 9. Right: weak staining, index 2. Strong staining of stromal cell nuclei was noted (arrow). Bar: 100 microns. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot of biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy for men with weak staining (4 or less; blue) or moderate to strong staining (>4, green)

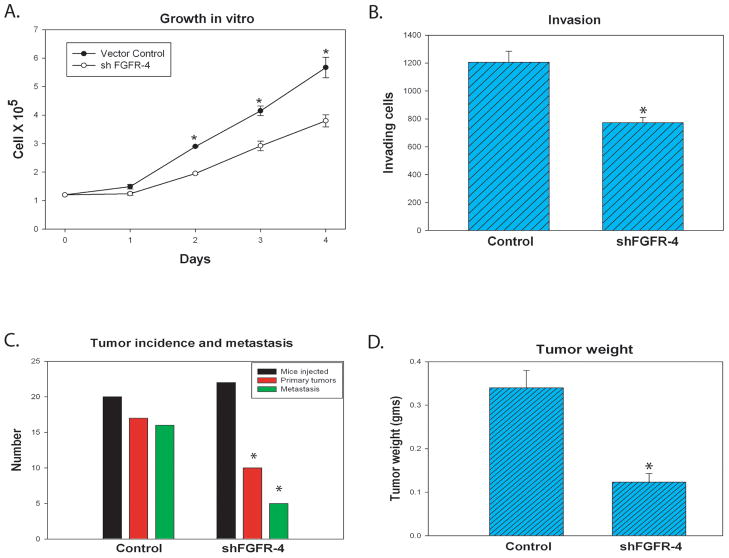

The FGFR-4 Arg388 promotes prostate cancer growth and metastasis

To determine if FGFR-4 impacts tumor growth and metastasis of PCa cells in vivo we derived PC3 prostate cancer cells expressing a shRNA targeting FGFR-4 cells using a lentivirus vector. FGFR-4 mRNA was decreased by 72% in these cells compared to PC3 scramble shRNA control cells. We found a significant inhibition of proliferation (Fig 6A) and invasion (Fig 6B) in vitro in the shFGFR-4 PC3 cells compared to vector controls. We then evaluated primary tumor growth and metastatic potential in an orthotopic model in which shFGFR-4 or scramble shRNA control cells are injected directly into the prostates of nude mice for each group. In this model cancer cells grow initially in a native prostatic environment and metastasize to pelvic and abdominal lymph nodes. We sacrificed mice 7 weeks after injection, weighed all tumors and submitted primary tumors and lymph nodes for histopathological analysis. FGFR-4 knockdown significantly inhibited tumorigenicity in this model (p=.01, Fisher exact test). As shown in Fig 6D, in mice with pathologically confirmed primary tumors, primary tumor weight was decreased 63% in shFRGR-4 tumors (p=.02, t-test) and the proportion of mice with lymph node metastasis was decreased from 16 of 17 to 5 of 10 (Fig 6C; p=.02, Fisher).Thus, in PC3 cells decreased expression of FGFR-4 mRNA is associated with impaired progression both at the primary and metastatic sites.

Figure 6. Knockdown of FGFR-4 in PC3 cells decreases proliferation, invasion, tumor growth and metastasis.

PC3 cells were established expressing a shRNA targeting FGFR-4 or control scramble shRNA. (A) Proliferation assays. Cells were plated at 1.2 ×105 cells/60 mm dish in 10% serum and growth monitored using a Coulter counter each day for 4 days. (B) Matrigel invasion assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods using PC3 shFGFR-4 and control cells. Mean and SD of triplicates shown. Statistically significant differences by t-test are indicated by an asterisk. (C and D) PC3 shFGFR-4 and control cells were injected orthotopically into the prostate of nude mice and necropsy performed 7 weeks after injection. Numbers of mice injected, number with primary tumors and number with confirmed metastatic lesions are shown in (C); D shows the mean weight of primary tumors (+/−SEM). Significant differences by Fisher exact test (C) or t-test (D) are indicated by an asterisk.

It should be noted that the mean size of primary tumors in mice without metastasis was smaller than that of primary tumors in mice with metastasis in the group injected with shFGFR-4 cells (74 Vs 172 mg) but this difference was not statistically significant (p=.08, t-test). Thus it is difficult to conclusively disentangle effects of FGFR-4 on primary tumor growth and metastasis. This experiment was repeated in a second, independent set of PC3 shFRGR-4 cells and controls with similar results (data not shown). It should be noted that PC3 cells are homozygous for the Arg388 allele, so that this effect is mediated by downregulation of this variant.

DISCUSSION

Increased expression of FGFR-4 and its ligands such as FGF8 and FGF17 in human PCa specimens have been correlated with aggressive clinical behavior (4–6, 39) including bone metastasis (4) and PCa specific mortality (6). In addition, the presence of the FGFR-4 Arg388 polymorphism has been associated with more aggressive disease in PCa (7, 40) and other malignancies (10–12, 14–15). We have now shown that expression of FGFR-4 Arg388 leads to activation of SRF and AP1 mediated transcription, primarily via ERK signaling. The transcriptional program induced by FGFR-4 Arg388 signaling is associated with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. In vitro, SRF and ERK activation by FGFR-4 Arg388 are associated with increased invasion. In vivo, knockdown of FGFR-4 Arg388 in PC3 cells results in decreased tumorigenicity, primary tumor growth and metastasis. It should be noted that while the FGFR-4 Arg388 variant is more potent at promoting invasion, knockdown of FGFR-4 in DU145 cells (which are homozygous Gly388) markedly inhibits invasion (39) and our data indicates that FGFR-4 Gly388 activates ERK, although to a lesser extent than the Arg388 isoform. Thus both variants probably contribute to the observed correlation of FGFR-4 expression with aggressive clinical behavior in PCa.

There have been few studies of the role of SRF in PCa. Our data indicates that SRF is expressed in 80% of human PCas. Moderate to high levels are present about half of human PCas and elevated expression is associated with aggressive clinical features. It is not clear how SRF protein levels are regulated in PCa cells. It is known that the miR-133 microRNA can target SRF (41) and we have shown that miR-133 is downregulated in human PCa tissues (42) so that it is possible that miR-133 downregulation can increase SRF protein levels in some PCas. Increased levels of SRF protein can potentially enhance cellular response to growth factor activation of the SRF cofactor ELK1 by ERK by increasing total transcription factor complex formation. It is well known that SRF promotes both proliferation and cell migration (reviewed in (43)), consistent with our observations that SRF promotes invasion in vitro. The Tindall laboratory has shown that the androgen receptor (AR) coactivator FHL2 is an SRF target gene (44). Knockdown of SRF inhibits androgen induction of FHL2, transcription of AR target genes and proliferation in LNCaP cells. Thus SRF can promote AR activity in prostate cancer, which may be important in its activity in promoting PCa progression.

The role of the ERK pathway in prostate cancer has not been examined to the same extent as other pathways such as the PI3K pathway. Studies in mouse models have provided evidence that the ERK and PI3K pathways can cooperate in prostate carcinogenesis (45). Sprouty proteins, which negatively regulate ERK signaling in response to FGFR activation, are down regulated in PCa (26), suggesting there is pressure to enhance FGFR mediated ERK activation in PCa. The extent to which ERK activity in PCa cells is dependent on FGFR signaling in general and FGFR-4 signaling in particular is unclear. In breast cancer cells, knockdown of FGFR-4 lead to decreased ERK activation (46). Further studies are needed to define the relative importance of FGFRs in comparison to other growth factor receptors in activating ERK in prostate cancer. However, given our finding that knockdown of FGFR-4 in prostate cancer cells significantly decreases proliferation, invasion, tumorigenicity, primary tumor growth and metastasis, it seems likely that that this contribution is substantial. It should be noted ERK signaling can also enhance AR signaling (47), making it a particularly attractive therapeutic target in prostate cancer.

It is established that FGF receptor signaling leads to activation of PLC-γ signaling. The NFAT transcription factor can potentially be activated via PLC-γ mediated increase in intracellular calcium. However, we did not observe any difference in NFAT transcriptional activity between FGFR-4 Arg388 and Gly388 expressing PNT1a cells in our luciferase reporter studies. There are two potential explanations. One is that there is no difference between the two receptor isoforms in PLC-γ signaling. Alternatively, FGFR-4 mediated PLC-γ signaling may not activate NFAT signaling. Studies by Thebault et al (48) in prostate epithelial cells indicate that while different ligands can both activate PLC-γ signaling, some do not activate NFAT signaling due to differences in activation in TRPC calcium channels. Further studies are needed to understand the impact of FGFR-4 signaling on NFAT transcriptional activity.

Immunohistochemical studies in human PCa linking FGFR-4 expression to lethal prostate cancer and the studies reported here indicate that inhibition of FGFR-4 is an important potential therapeutic target in prostate cancer. A number of approaches to inhibiting FGFR activity (49), including FGFR-4 specific approaches (46) are currently under development. Several studies have shown that FGFR-4 activation can enhance resistance to chemotherapy (46, 50), so combination therapeutic approaches with either classic chemotherapy or other targeted agents are most likely to be successful.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by grants from the Dept of Veterans Affairs Merit Review (MI), the DOD Prostate Cancer Research program (W81XWH-09-1-0172; WY), the NCI to the Tumor Microenvironment Network (1U54CA126568), the Baylor Prostate Cancer SPORE (P50CA058204) and the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center (P30CA125123) and by the use of the facilities of the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC.

The assistance of Yiqun Zhang with analysis of microarray expression data is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Kwabi-Addo B, Ozen M, Ittmann M. The role of fibroblast growth factors and their receptors in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:709–24. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:139–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ropiquet F, Giri D, Kwabi-Addo B, Mansukhani A, Ittmann M. Increased expression of fibroblast growth factor 6 in human prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4245–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valta MP, Tuomela J, Bjartell A, Valve E, Vaananen HK, Harkonen P. FGF-8 is involved in bone metastasis of prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:22–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heer R, Douglas D, Mathers ME, Robson CN, Leung HY. Fibroblast growth factor 17 is over-expressed in human prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2004;204:578–86. doi: 10.1002/path.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy T, Darby S, Mathers ME, Gnanapragasam VJ. Evidence for distinct alterations in the FGF axis in prostate cancer progression to an aggressive clinical phenotype. J Pathol. 2010;220:452–60. doi: 10.1002/path.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J, Stockton DW, Ittmann M. The fibroblast growth factor receptor-4 Arg388 allele is associated with prostate cancer initiation and progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6169–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gowardhan B, Douglas DA, Mathers ME, McKie AB, McCracken SR, Robson CN, et al. Evaluation of the fibroblast growth factor system as a potential target for therapy in human prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:320–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu B, Tong N, Chen SQ, Hua LX, Wang ZJ, Zhang ZD, et al. FGFR4 Gly388Arg polymorphism contributes to prostate cancer development and progression: A meta-analysis of 2618 cases and 2305 controls. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bange J, Prechtl D, Cheburkin Y, Specht K, Harbeck N, Schmitt M, et al. Cancer progression and tumor cell motility are associated with the FGFR4 Arg(388) allele. Cancer Res. 2002;62:840–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spinola M, Leoni V, Pignatiello C, Conti B, Ravagnani F, Pastorino U, et al. Functional FGFR4 Gly388Arg polymorphism predicts prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma patients. JClin Oncol. 2005;23:7307–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.17.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Streit S, Bange J, Fichtner A, Ihrler S, Issing W, Ullrich A. Involvement of the FGFR4 Arg388 allele in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:213–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.da Costa Andrade VC, Parise O, Jr, Hors CP, de Melo Martins PC, Silva AP, Garicochea B. The fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 (FGFR4) Arg388 allele correlates with survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;82:53–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Streit S, Mestel DS, Schmidt M, Ullrich A, Berking C. FGFR4 Arg388 allele correlates with tumour thickness and FGFR4 protein expression with survival of melanoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1879–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morimoto Y, Ozaki T, Ouchida M, Umehara N, Ohata N, Yoshida A, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism in fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 at codon 388 is associated with prognosis in high-grade soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2245–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seitzer N, Mayr T, Streit S, Ullrich A. A single nucleotide change in the mouse genome accelerates breast cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2010;70:802–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monsonego-Ornan E, Adar R, Feferman T, Segev O, Yayon A. The transmembrane mutation G380R in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 uncouples ligand-mediated receptor activation from down-regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:516–22. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.516-522.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho JY, Guo C, Torello M, Lunstrum GP, Iwata T, Deng C, et al. Defective lysosomal targeting of activated fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 in achondroplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:609–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237184100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Yu W, Cai Y, Ren C, Ittmann MM. Altered fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 stability promotes prostate cancer progression. Neoplasia. 2008;10:847–56. doi: 10.1593/neo.08450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dakhova O, Ozen M, Creighton CJ, Li R, Ayala G, Rowley D, et al. Global gene expression analysis of reactive stroma in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3979–89. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saldanha AJ. Java Treeview--extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3246–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glinsky GV, Glinskii AB, Stephenson AJ, Hoffman RM, Gerald WL. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:913–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI20032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creighton CJ, Casa A, Lazard Z, Huang S, Tsimelzon A, Hilsenbeck SG, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I activates gene transcription programs strongly associated with poor breast cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4078–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai Y, Wang J, Li R, Ayala G, Ittmann M, Liu M. GGAP2/PIKE-a directly activates both the Akt and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways and promotes prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2009;69:819–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murthy S, Marcelli M, Weigel NL. Stable expression of full length human androgen receptor in PC-3 prostate cancer cells enhances sensitivity to retinoic acid but not to 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Prostate. 2003;56:293–304. doi: 10.1002/pros.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwabi-Addo B, Wang J, Erdem H, Vaid A, Castro P, Ayala G, et al. The expression of Sprouty1, an inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor signal transduction, is decreased in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4728–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gary-Bobo G, Parlakian A, Escoubet B, Franco CA, Clement S, Bruneval P, et al. Mosaic inactivation of the serum response factor gene in the myocardium induces focal lesions and heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:635–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall DJ, Rudnick KA, McCarthy SG, Mateo LR, Harris MC, McCauley C, et al. Interleukin-18 enhances Th1 immunity and tumor protection of a DNA vaccine. Vaccine. 2006;24:244–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashida S, Nakagawa H, Katagiri T, Furihata M, Iiizumi M, Anazawa Y, et al. Molecular features of the transition from prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) to prostate cancer: genome-wide gene-expression profiles of prostate cancers and PINs. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5963–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer DH, Hussain SA, Ganesan R, Cooke PW, Wallace DM, Young LS, et al. CD40 expression in prostate cancer: a potential diagnostic and therapeutic molecule. Oncol Rep. 2004;12:679–82. doi: 10.3892/or.12.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giri D, Ropiquet F, Ittmann M. Alterations in expression of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 2 and its receptor FGFR-1 in human prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1063–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miano JM. Role of serum response factor in the pathogenesis of disease. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1274–84. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X, Ge H, Gupte J, Weiszmann J, Shimamoto G, Stevens J, et al. Co-receptor requirements for fibroblast growth factor-19 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29069–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang J, Mohammadi M, Rodrigues GA, Schlessinger J. Reduced activation of RAF-1 and MAP kinase by a fibroblast growth factor receptor mutant deficient in stimulation of phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5065–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li R, Wheeler T, Dai H, Frolov A, Thompson T, Ayala G. High level of androgen receptor is associated with aggressive clinicopathologic features and decreased biochemical recurrence-free survival in prostate: cancer patients treated with radical prostatectomy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:928–34. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200407000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dai H, Li R, Wheeler T, Diaz de Vivar A, Frolov A, Tahir S, et al. Pim-2 upregulation: biological implications associated with disease progression and perinueral invasion in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2005;65:276–86. doi: 10.1002/pros.20294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayala G, Tuxhorn JA, Wheeler TM, Frolov A, Scardino PT, Ohori M, et al. Reactive stroma as a predictor of biochemical-free recurrence in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4792–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maru N, Ohori M, Kattan MW, Scardino PT, Wheeler TM. Prognostic significance of the diameter of perineural invasion in radical prostatectomy specimens. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:828–33. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.26456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahadevan K, Darby S, Leung HY, Mathers ME, Robson CN, Gnanapragasam VJ. Selective over-expression of fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 4 in clinical prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2007;213:82–90. doi: 10.1002/path.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma Z, Tsuchiya N, Yuasa T, Inoue T, Kumazawa T, Narita S, et al. Polymorphisms of fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 have association with the development of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia and the progression of prostate cancer in a Japanese population. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2574–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, et al. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2006;38:228–33. doi: 10.1038/ng1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozen M, Creighton CJ, Ozdemir M, Ittmann M. Widespread deregulation of microRNA expression in human prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:1788–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miano JM, Long X, Fujiwara K. Serum response factor: master regulator of the actin cytoskeleton and contractile apparatus. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C70–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00386.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heemers HV, Regan KM, Dehm SM, Tindall DJ. Androgen induction of the androgen receptor coactivator four and a half LIM domain protein-2: evidence for a role for serum response factor in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10592–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao H, Ouyang X, Banach-Petrosky WA, Gerald WL, Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Combinatorial activities of Akt and B-Raf/Erk signaling in a mouse model of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14477–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606836103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roidl A, Berger HJ, Kumar S, Bange J, Knyazev P, Ullrich A. Resistance to chemotherapy is associated with fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 up-regulation. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2058–66. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agoulnik IU, Bingman WE, 3rd, Nakka M, Li W, Wang Q, Liu XS, et al. Target gene-specific regulation of androgen receptor activity by p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2420–32. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thebault S, Flourakis M, Vanoverberghe K, Vandermoere F, Roudbaraki M, Lehen’kyi V, et al. Differential role of transient receptor potential channels in Ca2+ entry and proliferation of prostate cancer epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2038–47. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turner N, Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:116–29. doi: 10.1038/nrc2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thussbas C, Nahrig J, Streit S, Bange J, Kriner M, Kates R, et al. FGFR4 Arg388 allele is associated with resistance to adjuvant therapy in primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3747–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.