Abstract

PACAP (pituitary adenylyl cyclase activating peptide, ADCYAP1) is a neuropeptide that regulates a wide array of functions within the brain and periphery. We and others have previously demonstrated that PACAP and its high-affinity receptor PAC1 are expressed in the embryonic mouse neural tube, suggesting that PACAP plays a role in early brain development. Moreover, we previously showed that PACAP antagonizes the mitotic action of Sonic hedgehog (Shh) in postnatal cerebellar granule precursors. In the present study, we demonstrate that PACAP completely blocked Shh-dependent motor neuron generation from embryonic stem cell cultures and reduced mRNA levels of the Shh target gene Gli-1 and several ventral spinal cord patterning genes. In vivo examination of motor neuron and other patterning markers in embryonic day 12.5 spinal cords of wild type and PACAP-deficient mice by immunofluorescence, on the other hand, revealed no obvious alterations in expressions of Islet1/2, MNR2, Lim1/2, Nkx2.2, and Shh, although Pax6-positive area was slightly expanded in PACAP-deficient spinal cord. Caspase-3 staining revealed low, and similar numbers of cells undergoing apoptosis in embryonic wild type vs. PACAP-deficient spinal cords, whereas a slight, but significant increase in number of mitotic cells was observed in PACAP-deficient mice. Thus, while PACAP has a strong capacity to counteract Shh signaling and motor neuron production in vitro, corresponding patterning defects associated with PACAP loss may be obscured by compensatory mechanisms.

Keywords: embryonic stem cells, motor neuron, mouse, neuropeptide, PACAP, spinal cord

Introduction

PACAP is a neuropeptide closely related to vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) that functions as a neurotransmitter and immunomodulator and has been implicated in a variety of developmental actions (Arimura, 1998; Sherwood et al., 2000; Vaudry et al., 2000; Delgado et al., 2004). With respect to the latter, PACAP has been shown to regulate neural precursor cell proliferation, maturation, and survival during central nervous system (CNS) development (Waschek, 1996; Lu et al., 1998; Waschek et al., 1998; Nicot & DiCicco-Bloom, 2001; Watanabe et al., 2007). We previously showed that PACAP and the PACAP-specific receptor PAC1 genes are expressed in a complementary manner in the hindbrain and spinal cord of embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5) mice; receptor transcripts were more prominently found in the dorsal region and in the floor plate within the ventricular zone, while the transcripts for the ligand were found in the newly differentiating cells just outside the ventricular zone (Waschek et al., 1998). Moreover, PACAP stimulated the production of cAMP in a dose dependent manner in E10.5 hindbrain cell cultures, suggesting that the PACAP/PAC1 system may be important regulators of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A activity in the embryonic CNS. As protein kinase A is known as a common negative regulator of hedgehog signaling in fly embryos (Pan & Rubin, 1995; Li et al., 1995) and in the vertebrate neural tube (Hammerschmidt et al., 1996; Epstein et al., 1996), factors that stimulate cAMP might be expected to antagonize patterning or other actions of Shh. Consistent with this possibility, we found that these hindbrain cultures responded to exogenous PACAP with a decrease expression of the sonic hedgehog (Shh) target gene Gli-1 (Waschek et al., 1998).

A major action of Shh during spinal cord development is to regulate the production of ventral neuronal phenotypes (Roelink et al., 1995; Martí et al., 1995; Dessaud et al., 2008), including motor neurons (Tanabe et al., 1995; Ericson et al., 1996). The fact that PACAP inhibited the expression of the Shh target gene Gli-1 in hindbrain cultures suggested that PACAP might act to modulate the patterning actions of Shh in the neural tube and perhaps motor neuron production. In other work, mRNAs for PACAP and its receptors were shown to be expressed in embryonic stem (ES) cells and ES cell-derived neuronal cells (Cazillis et al., 2004; Hirose et al., 2005). Moreover, PACAP differentiates cultured ES cells towards a neuronal phenotype (Cazillis et al., 2004). However, the ability of PACAP to regulate the production of motor neurons or other specific neuronal phenotypes in ES cultures has not been reported.

Cultures of mouse ES cells can reliably generate spinal motor neurons in the presence of retinoic acid and Shh (Wichterle et al., 2002). We used this assay system to determine if exogenous PACAP could block Shh signaling and induction of motor neurons. Finally, to determine the requirement of endogenous PACAP in spinal cord development, we performed morphometric studies, immunohistochemistry, and mitotic and apoptotic labeling on wild-type (WT) and PACAP-deficient (KO) mouse embryos.

Materials and Methods

Animals

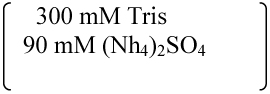

Animals were maintained, housed and fed ad libitum at the UCLA School of Medicine vivarium. In all studies, the recommendations for animal use and welfare, as established by the UCLA Division of Laboratory Animals and the guidelines from the National Institutes of Health, were followed. The generation of mice with targeted mutation in the PACAP genes were previously described (Colwell et al., 2004). All animals used in the present studies were backcrossed for at least twelve generations unto a C57BL/6J genetic background. The day a vaginal plug was observed was designated as embryonic day 0.5 (i.e., E0.5). All embryos were generated from heterozygous parings. Genotyping was performed as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Touchdown PACAP PCR genotyping protocol.

| PCR primers (Invitrogen Cat. # 10336022) | ||||

| omPCPF1+: GTT ATG TCG GTG CGG AGG AGT TTC | ||||

| omPCPD2−: GCT GGA TAG TAA AGG GCG TAA | ||||

| omPCPF2−: TTC AAG CAG CCT GCC CCA GAC TCA | ||||

| RXN | 1X | |||

| DNA | 150 ng/sample | |||

| MgSO4 | (25 mM) | 6 µL | ||

| 5X Buffer, pH 9.15 |  |

10 µL | ||

| 6 mM MgSO4 | ||||

| dNTP’s mix | (2.5 mM each) (Ambion cat #: 8228 G) | 4 µL | ||

| *omPCPF1+ (10 µM) | 3 µL | |||

| *omPCPF2− (10 µM) | 3 µL | |||

| *omPCPD2− (10 µM) | 1.5 µL | |||

| DMSO | 1.0 µL | |||

| Titanium Taq (BDBiosciences Clontech cat #: 639208) | 0.4 µL | |||

| Pfu Native (Stratagene cat #: 600136) | 0.1 µL | |||

| ddH2O | 19 µL | |||

| TOTAL | 50 µL | |||

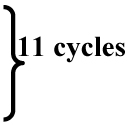

| PCR program: | ||||

| 95 °C - 5 mins | ||||

| 94 °C – 1:00 min |  |

|||

| 70 °C – 30s | ||||

| Decrease temp by 1°C every 1 cycle | ||||

| 72 °C – 4:30 mins | ||||

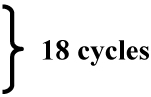

| 94 °C – 1:00 min |  |

|||

| 60 °C – 30s | ||||

| 72 °C – 4:30 mins | ||||

| 72 °C – 7 mins | ||||

| 4 °C – 20 mins | ||||

| 25 °C – ∞ | ||||

| EXPECTED FRAGMENT SIZES:WT 1.3 Kb; mutant 1.7 Kb | ||||

In Situ Hybridization with Digoxigenin-Labeled Riboprobe

E12.5 mouse embryos were immersion-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight at 4°C. After cryoprotection in 30% sucrose in PBS, embryos were frozen in OCT embedding compound (Tissue-Tek) (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA, USA). DIG-labeled riboprobes for PACAP and PAC1 were synthesized from the same templates as described in Waschek et al. (1998) using DIG RNA labeling kit (Roche). Subsequently they were purified using RNAse-free Micro Bio-Spin columns (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and quantified using DIG nucleic acid detection kit (Roche). The PACAP probe was submitted to limited alkaline lysis in carbonate buffer at 60°C for 10 min prior to hybridization. Cryostat sections (20 µm) from E12.5 embryos (fresh-frozen in OCT on dry ice) were fixed onto Superfrost slides (Fisher Scientific), stored at −80°C, then assayed as described by Fuss et al, with minor modifications (Fuss et al., 1993). Briefly, slides were fixed for 5 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with proteinase K, postfixed in paraformaldehyde, treated with 0.1 M triethanolamine (pH 8.0), then with 0.1 M triethanolamine with 0.25% acetic anhydride. Sections were then dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol and hybridized with sense and antisense riboprobes overnight at 55°C (PACAP) or 65°C (PAC1). After hybridization, sections were washed at room temperature for 30 min in 2× SSC, then at 72°C for 1 hour in 2× SSC, then at 72°C for 1 hour in 0.1× SSC. Slides were then probed with anti-digoxigenin-HRP followed by detection using the Renaissance TSA-biotin kit (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and streptavidin-FITC according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For PACAP, a second round of amplification using streptavidin-HRP and biotinyl-tyramide was performed to enhance the signal. When Pax6 immunohistochemistry was performed in parallel to PAC1 ISH, the incubation with anti-Pax6 antibody was carried out overnight after incubation of sections with biotinyl tyramide but before incubation with streptavidin-FITC. The secondary antibody (anti-mouse-Cy3) was added to the sections together with streptavidin-FITC the next day.

Cell culture

HB9::GFP transgenic mouse-derived (HBG3) ES cells (Wichterle et al., 2002) were cultured on mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder layer in ES cell media (Wichterle et al., 2002) for 2 days. ES culture media: DMEM + 15% fetal calf serum (HyClone) + 2 mM L-glutamine + penicillin/streptomycin + non-essential amino acids + nucleosides + 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol + 1000U/mL LIF (ESGRO, Chemicon). DFK10 media: DMEM:F12 + 10% knockout serum replacement (Invitrogen) + penicillin/streptomycin + 2.4% N2 supplement + 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol + 1U/mL heparin. The cells were then detached using TrypLE Express trypsin substitute (Invitrogen) and plated at 50,000 cells/ml on bacterial Petri dishes in DFK10 media (Miles et al., 2004). The media was changed after 1 day and on the second day the forming embryoid bodies (EBs) were plated in DFK10 media supplemented with 1 µM retinoic acid (Sigma) with or without purmorphamine (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) and/or PACAP38 (Calbiochem) at indicated concentrations. At indicated time points after the addition of retinoic acid to the culture media (6h - 5 days) the EBs were collected by gentle centrifugation and mounted on slides in Vectashield anti-fade medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) or submitted to RNA extraction procedure as indicated below. A total of 6–8EB/s from 2–3 independent wells were counted. Each EB was treated as a replicate.

Microscopic evaluation of HB9 expression

Embryoid bodies mounted in Vectashield on glass slides were randomly selected from each sample (6–8 EBs/sample) and photos of GFP fluorescence were taken using the microscope (IX70, OLYMPUS) with the exposure time set to a constant value between samples. The region of the image containing the EB was marked based on DAPI staining, and the mean fluorescence intensity in this region in the green channel was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH).

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

RNA extraction was performed using the TriZol reagent (Invitrogen) or Stat-60 RNA/mRNA isolation reagent (IsoTex Diagnostics, Friendswood, Texas, USA) according to manufacturers’ instructions. Genomic DNA contamination was eliminated using Turbo DNA-free kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) or SuperScript II preamplification system (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR-green iQ kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and the quantification of relative gene expression values was performed using the standard curve method with GAPDH used as the reference housekeeping gene or by normalizing to 18S RNA levels. Each primer pair was validated by cloning and sequencing of the PCR product. Primer sequences were as follows: GAPDH, 5'-GGC CTT CCG TGT TCC TAC-3' (forward); 5'-TGT CAT CAT ACT TGG CAG GTT-3' (reverse), Gli-1, 5'-ATC TCT CTT TCC TCC TCC TCC-3' (forward); 5'-CGA GGC TGG CAT CAG AA-3' (reverse), HB9, 5'-GCT CAT GCT CAC CGA GAC TCA-3' (forward); 5'-GCT CTT TGG CCT TTT TGC TGC-3' (reverse), Pax6, 5'-AAA ATA GCC CAG TAT AAA CGG-3' (forward); 5'-GAC ACA CTG GGT ATG TTA TCG-3' (reverse), Nkx2.2, 5'-ACC TGG CCA GCC TCA TCC GTC-3' (forward); 5'-CTC CGC CCG GGC ACG TT-3' (reverse), Nkx6.1, 5'-GCG CGC CTT GCC TGT AC-3' (forward); 5'-TTG CTG TCC AGA GAA CGT GGG-3' (reverse), Islet2, 5'-GAA AGC ACT CAG CGA GTT TG-3' (forward); 5'-GCT ACC GGA AGA GTT GCC TA-3' (reverse).

Immunohistochemistry

The embryos were collected at E12.5, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in OCT compound, cryostat sectioned at 20 µm, mounted on Superfrost Plus slides and stored at −80°C. The following antibodies were used for immunohistochemistry on embryo sections: Islet1/2, MNR2, Lim1/2, Nkx2.2, Shh (all 1:20), neurofilament (165 kDa) (1:100) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, Iowa, USA), and Pax6 (1:500) (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA). Immunohistochemistry was performed using standard procedures. Briefly, slides were removed from the freezer and put on a slide warmer for approximately 1 hour to dry. After drying, the slides were washed 3× 5 min in PBS and blocked for 1 hour in a humid chamber at room temperature in 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100. The slides were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. The control sections were incubated in blocking solution. Afterwards, the slides were washed 3× 5 min in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 and incubated with secondary antibody (donkey anti-mouse Cy3 1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) in the blocking solution at 4°C overnight. For Pax6 the secondary antibody used was goat anti-rabbit-Cy2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) diluted 1:500 in blocking solution. The slides were then washed 3× 5 min in PBS and coverslipped with 90% glycerol, sealed with nail polish, and stored at 4°C until microscopic analysis. We examined evenly spaced sections from the length of spinal cord encompassing cervical, thoracic and lumber regions. To measure and compare Pax6 domains in WT vs. PACAP KO mice, the dimensions of Pax6-immunoreactive areas were determined as indicated in Fig. 7 using AxioVision 4.6 software (Zeiss). We evaluated Pax6-immunoreactive areas on seven pairs of WT and PACAP KO mice spinal cord.

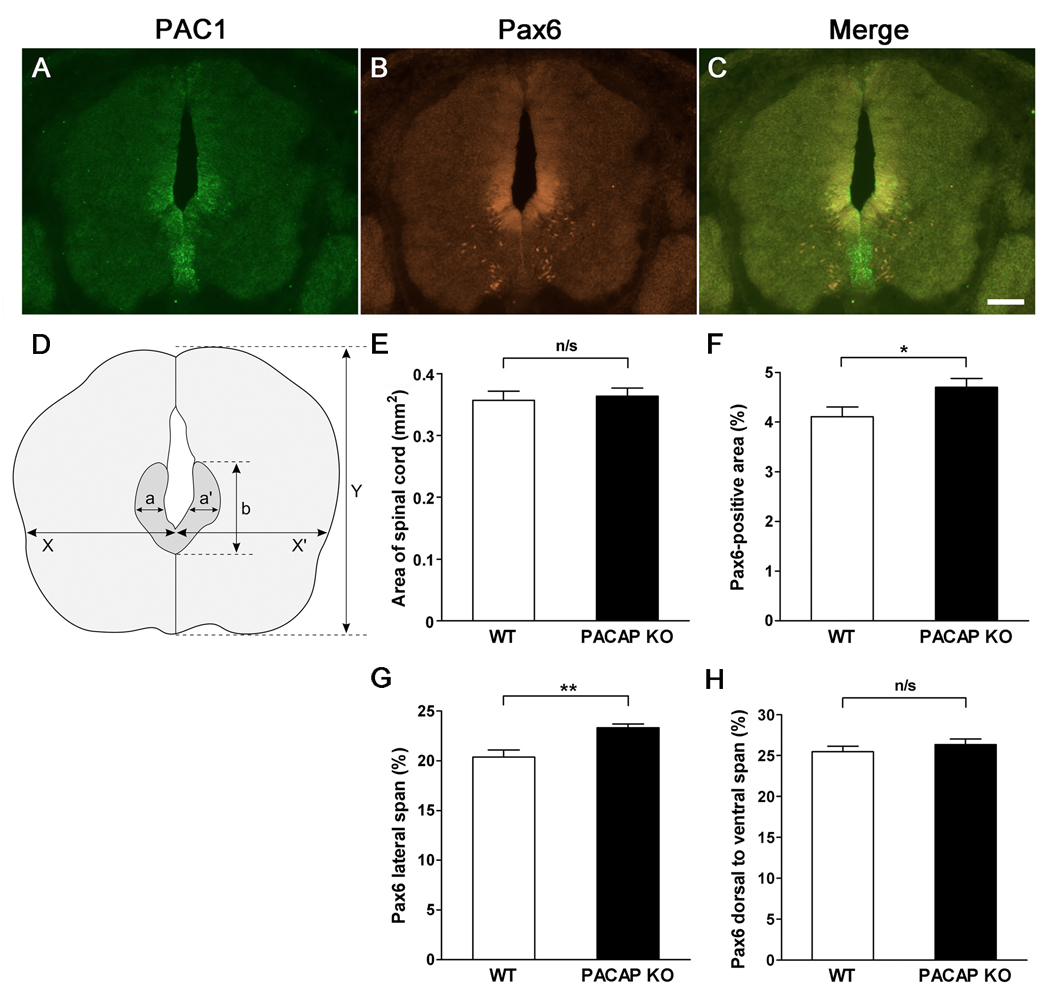

Figure 7. PACAP receptor (PAC1) gene expression in the ventricular zone (VZ) of mouse embryonic day 12.5 spinal cord, and expansion of the Pax6 domain in the dorsal portion of the basal plate VZ of PACAP-deficient mice.

(A) In Situ Hybridization with Digoxigenin-Labeled Riboprobe for PAC1. (B) Pax6 immunohistochemistry. (C) Merged image of PAC1 mRNA and Pax6 immunohistochemistry. Scale bar, 100 µm. (D) Dimensions of Pax6-positive area were measured as indicated. (E) Total spinal cord area in WT vs. PACAP KO mice. (F) Pax6-immnostained area expressed as a percentage of total area of spinal cord. (G) Lateral span of Pax6-immunostained area expressed as percentage of total spinal cord ((a+a’)/(X+X’) (%) in Fig. 7D). (H) Dorsal to ventral span of Pax6-immunostained area in spinal cord expressed as percentage of total spinal cord (b/Y (%) in Fig. 7D). n=7 for each genotype. Results expressed as mean ± SEM. n/s: non-significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Ki67 staining

Cell proliferation was evaluated by means of immunohistochemistry against Ki67 antigen in the ventricular zone of embryonic spinal cord on 20 µm sections. We evaluated Ki67 staining on 7 WT and 5 PACAP KO mice spinal cord. At least 12 evenly spaced sections from the length of spinal cord encompassing cervical, thoracic and lumber region. Sections were rinsed with PBS for 5 min. Sections were blocked for 1 hour in carrier solution (PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100, and 1% BSA) supplemented with 20% goat serum, then incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with 1:250 anti-Ki67 antibody (Vector Laboratories) in carrier solution supplemented with 5% goat serum. Following 3 washes with carrier solution, the slides were incubated with secondary Cy3-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit 1:300 in carrier solution for 40 min at room temperature, washed 3× in carrier solution, mounted and coverslipped.

Caspase-3 staining

Apoptotic cell death was measured by means of immunohistochemistry against activated (cleaved) caspase-3 in the 20 µm spinal cord sections. We evaluated caspase-3 staining on 4 pairs of WT and PACAP KO mice spinal cord. At least 16 evenly spaced sections from the length of spinal cord encompassing cervical, thoracic and lumber region were used for counting. Embryo sections were submitted to antigen retrieval by means of incubation with 10 mM sodium citrate, pH 6, at 95°C for 10 min. The slides were allowed to cool in the sodium citrate solution, then were washed 3× 10 min. with PBS. Sections were blocked for 1 hour in carrier solution supplemented with 20% goat serum, then incubated overnight at 4°C with 1:250 anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) in carrier solution supplemented with 5% goat serum. Following 3 PBS washes, the slides were incubated with secondary Cy3-conjugated goat-anti-mouse 1:300 in carrier solution for 1 hour at room temperature, washed 3× in PBS, mounted and coverslipped.

Statistical analyses

Differences between groups were evaluated by t-tests. Values were considered significantly different if p<0.05. In vitro and in vivo results were analyzed using Excel (Microsoft) and GraphPad Prism4 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) respectively. Results are shown as mean ± SEM.

Results

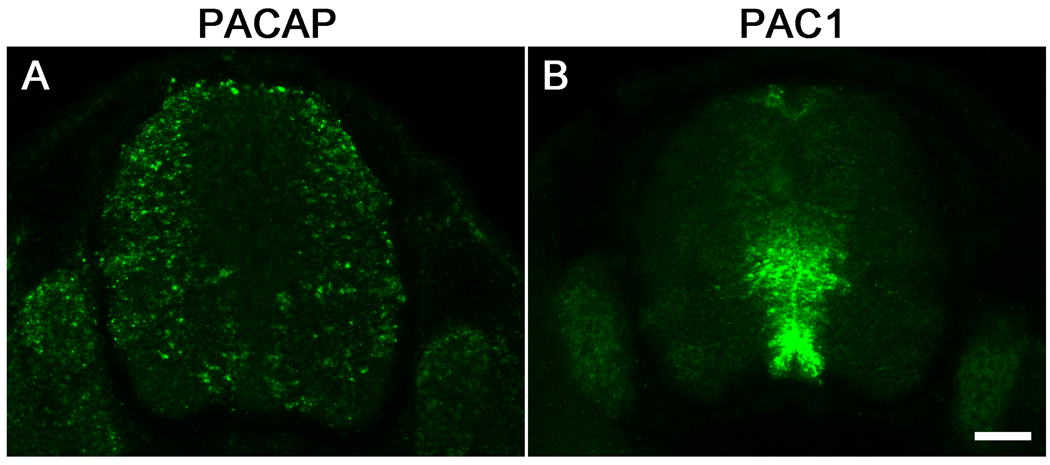

PACAP and PAC1 are expressed in the embryonic neural tube

PACAP and PAC1 mRNAs are first detected in the mouse embryonic neural tube at E9.5 to E10.5 (Waschek et al., 1998; Sheward et al., 1998). We focused our in vivo studies here at E12.5, a time when the patterning effects of PACAP were expected to be evident (2–3 days after the initial appearance of the transcripts). We first examined gene expression patterns of PACAP and the PAC1 receptor in the spinal cords of E12.5 mouse embryos by using non-radioactive in situ hybridization. Like at E10.5 (Waschek et al., 1998), we found that PAC1 receptor gene transcripts in the spinal cord were most concentrated in the ventricular zone. The expression was strongest near the dorsal portion of the basal plate ventricular zone, spreading out into the surrounding mantle area; also there was strong expression in the ventral ventricular zone, overlapping the P3 progenitor domain near the floor plate (Fig. 1B). PACAP gene transcripts were more peripheral, residing in the mantle layer, primarily in the dorsolateral spinal cord and spreading lower and more centrally into the ventral spinal cord (Fig. 1A). The non-overlapping, but complementary expression of PACAP and its receptor in the developing spinal cord at E12.5 was thus similar to what we observed at E10.5 (Waschek et al., 1998).

Figure 1. PACAP and PAC1 receptor gene expression in spinal cords of E12.5 mouse embryos.

(A) Non-radioactive in situ hybridization of PACAP expression. (B) Non-radioactive in situ hybridization of PAC1 receptor expression. Top is dorsal; Scale bar, 100 µm.

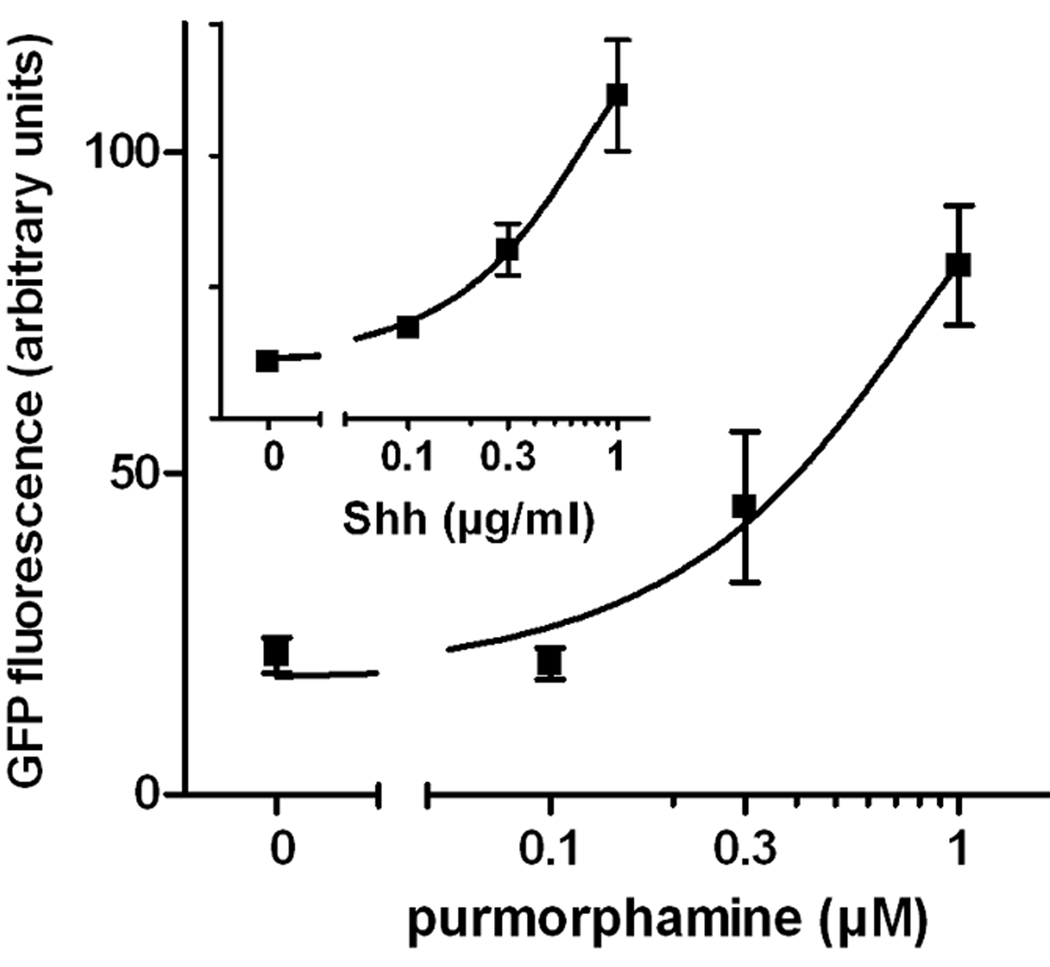

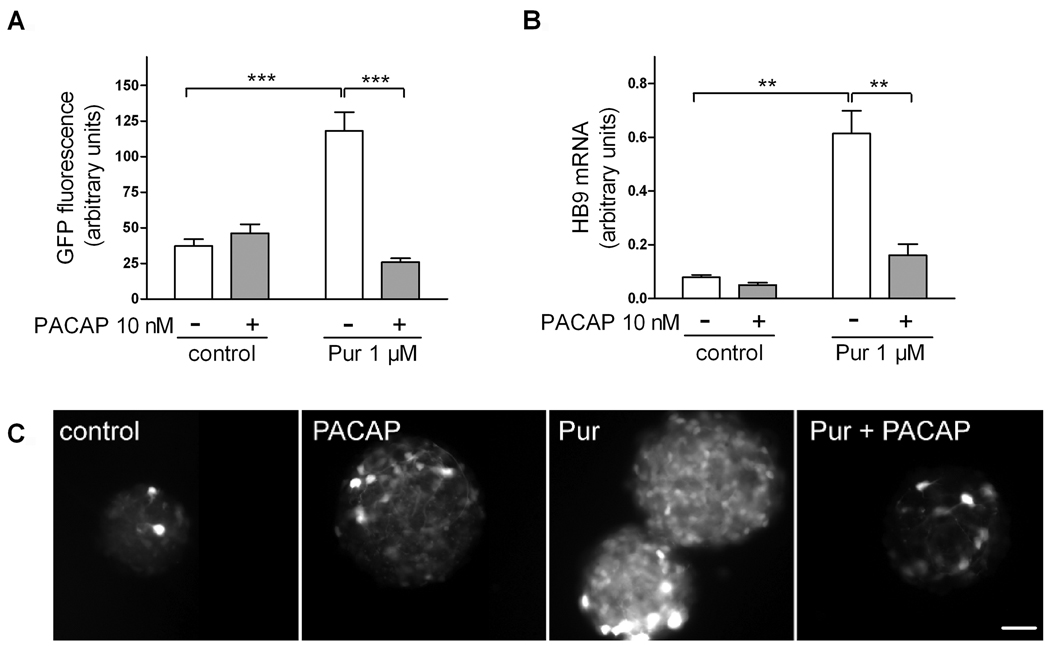

PACAP blocks hedgehog pathway-mediated ventral fate adoption in mouse embryoid body cultures

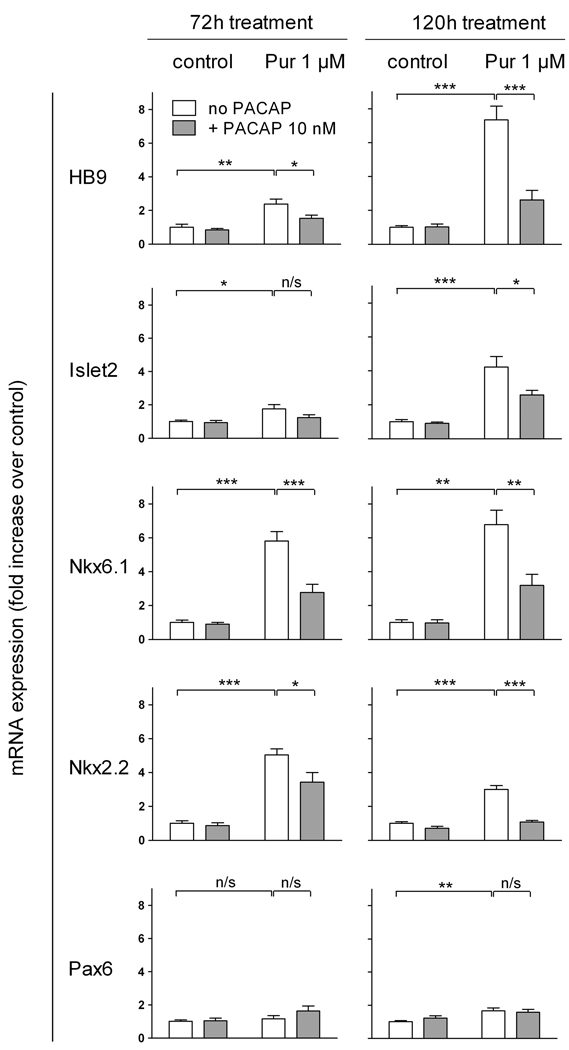

We previously demonstrated that 1) PACAP inhibited the expression of the hedgehog (Hh) target gene Gli-1 in cultured E10.5 embryonic hindbrain precursors (Waschek et al., 1998), 2) PACAP antagonized the actions of Shh on cultured cerebellar granule cell progenitors (Nicot et al., 2002), and 3) targeted deletion of a single copy of the PACAP gene promoted Hh pathway-mediated generation of medulloblastoma tumors (Lelievre et al., 2008). We therefore hypothesized that, in a similar fashion, PACAP might antagonize Shh actions in the spinal cord, in this case blocking Shh-induced specification of motor neurons and other ventral neuronal phenotypes. To study this, we used a transgenic mouse ES cell culture system in which motor neurons can be generated in embryoid bodies (EBs) and visualized by virtue of GFP expression driven by the motor neuron specific gene promoter (HB9). It has been previously shown that a large proportion of cells in ES-derived EBs begin to exhibit GFP fluorescence after approximately 3 days of treatment with retinoic acid and Shh, and strongly express GFP after 5 days (Wichterle et al., 2002). In our experiments, we treated cells for five days with retinoic acid and varying concentrations of purmorphamine, which directly activates the Hh pathway signal transducer smoothened, and with PACAP38. As expected, purmorphamine mimicked the effect of Shh and produced a dose-dependent increase in the expression of GFP in HB9::GFP EBs (Fig. 2). PACAP (10 nM) alone had no significant effect on GFP expression in these retinoic acid-treated cultures, but strongly antagonized the effect of 1 µM purmorphamine on GFP expression (Fig. 3A,C). To assess the induction of motor neurons by another method, we performed real-time RT-PCR mRNA analysis of HB9. Indeed, our results indicate that HB9 mRNA levels were increased by purmorphamine and reduced by co-treatment with PACAP (Fig. 3B). In another set of experiments, we treated cultures with purmorphamine and PACAP for three and five days and the determined mRNA levels of HB9 as well as several phenotypic markers and patterning genes (Fig. 4). These studies showed that purmorphamine-mediated inductions of HB9, as well as Islet2, a marker of motor neurons (Tsuchida et al., 1994), were time-dependent, with significant effects observable only after 5 days of treatment. Like HB9, the induction of Islet2 was significantly inhibited by PACAP. Interestingly, mRNAs for Nkx6.1, a homeobox transcription factor which participates in the differentiation of motor neurons as well as V2 and V3 neurons of the spinal cord (Sander et al., 2000), and for Nkx2.2, a marker specific V3 interneurons (Stone & Rosenthal, 2000) were already upregulated by purmorphamine after 3 days. These inductions persisted at 5 days, and were significantly blocked by PACAP at both time points. Neither purmorphamine nor PACAP induced significant changes in gene expression of Pax6, a transcription factor that acts in part as a mediator of Shh signaling to regulate the specification and/or phenotype of motor neurons and ventral interneurons (Ericson et al., 1997).

Figure 2. Smo agonist purmorphamine dose-dependently stimulates the expression of GFP in HB9::GFP embryoid bodies.

EBs were cultured for 5 days with 1 µM retinoic acid and purmorphamine (main graph) or Shh (inset) at indicated concentrations. Images of GFP fluorescence were taken for 6–9 EBs in each treatment group, and fluorescence was quantified using ImageJ. Error bars are SEM.

Figure 3. PACAP antagonizes the effect of purmorphamine on HB9:GFP expression in HB9::GFP embryoid bodies.

EBs were cultured for 5 days with 1 µM retinoic acid and purmorphamine (1 µM) and/or PACAP38 (10 nM). (A,C) Images of GFP fluorescence of 6–9 randomly chosen EBs were taken and average pixel intensity was calculated. Results are mean fluorescence intensity ± SEM. Representative images are shown in (C); scale bar is 100 µm. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of HB9 gene expression in EB extracts. Results are mean HB9 expression levels from 5–6 individual samples ± SEM. n/s: non-significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 4. PACAP antagonizes the effect of purmorphamine on the expression of ventral spinal cord markers in neuralized embryoid bodies.

EBs were cultured for 3 (72h) or 5 (120h) days with 1 µM retinoic acid and purmorphamine (1 µM) and/or PACAP38 (10 nM). Results are mean gene mRNA levels expressed as fold increase over control from 6–24 individual samples ± SEM. n/s: non-significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

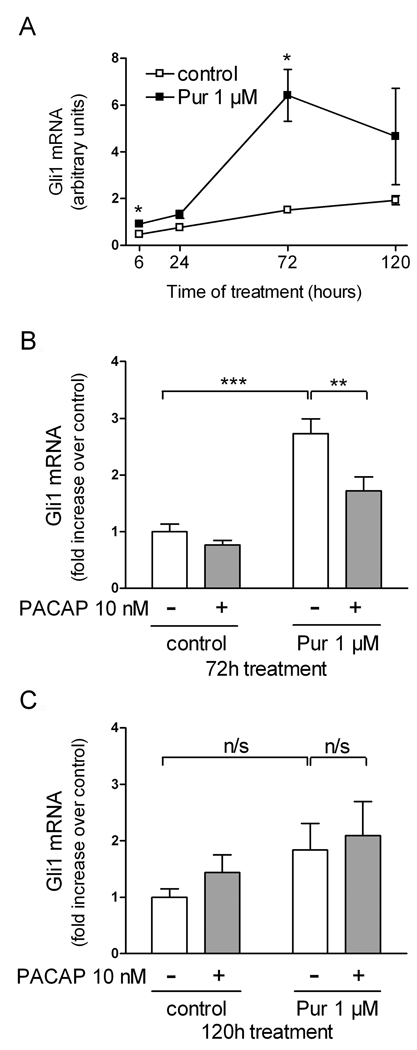

These data indicate that PACAP acts in EBs to inhibit Hh pathway-mediated ventral neuron specification. To determine if PACAP inhibited these actions by interfering with the canonical Hh signal transduction pathway, we measured the levels of Gli-1 mRNA, a direct transcriptional target of Hh. First, we determined at what time points in culture the Hh target gene Gli-1 was induced by purmorphamine. After 6 and 24 hours of treatment, there were borderline significant inductions of Gli-1 mRNA levels (~2-fold; p=0.043 and 0.065, respectively) by purmorphamine. After 3 days of treatment, a highly significant ~4-fold induction was observed. After 5 days, the mean Gli-1 mRNA level was still higher than controls, although not significantly, possibly due to a high variability of values at this time point (Fig. 5A). PACAP produced a significant inhibition of purmorphamine-stimulated Gli-1 gene expression at 3 days (Fig. 5B) and like purmorphamine, no longer had significant effects on Gli-1 mRNA after 5 days of treatment (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. PACAP antagonizes the effect of purmorphamine on Gli1 mRNA in neuralized embryoid bodies.

(A) Time course of Gli1 gene expression. EBs were cultured with 1 µM retinoic acid with or without purmorphamine (1 µM) for the indicated number of hours. Results are mean Gli1 mRNA levels (arbitrary units) from 5–6 individual samples ± SEM. (B,C) EBs cultured for 3 (B) or 5 (C) days with 1 µM retinoic acid and purmorphamine (1 µM) and/or PACAP38 (10 nM). Results are mean Gli1 mRNA levels expressed as fold increase over control from 6–18 individual samples ± SEM. n/s: non-significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Targeted deletion of the PACAP gene results in expansion of the Pax6-positive domain in the embryonic spinal cord

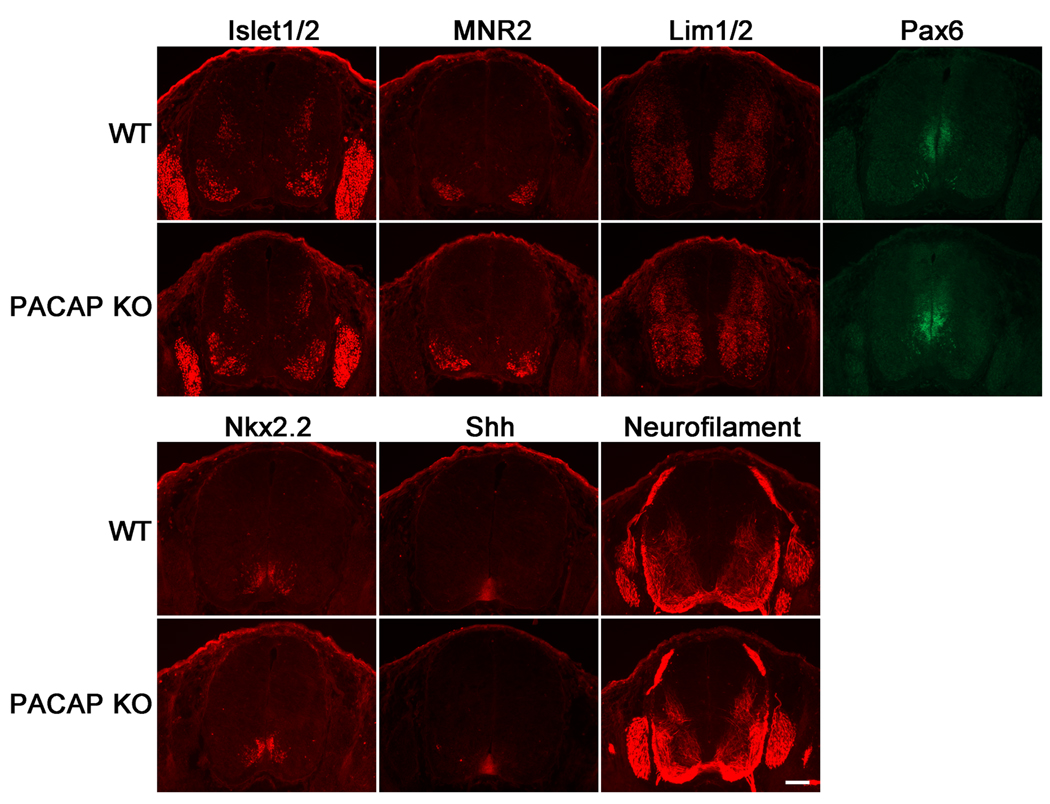

To investigate the effects of PACAP deficiency on spinal cord patterning in vivo we stained WT and PACAP KO E12.5 embryonic spinal cord sections with a panel of antibodies recognizing proteins that either play a role in specifying, or that mark neural fates in the neural tube. Despite the clear actions of exogenous PACAP on motor neuron production of ES cells/EB cultures, we found no obvious effect of PACAP loss at this time point on the distributions of Islet1/2- or MNR2-stained spinal cord motor neurons, or of cells labeled with the motor neuron/interneuron marker Lim1/2 (Tsuchida et al., 1994; Tanabe et al., 1998), or the V3 ventral interneuron Nkx2.2 marker (Fig. 6). Moreover, the pattern of the axon marker neurofilament (165 kDa) did not obviously differ between normal and PACAP KO embryos. On the other hand, the Pax6 domain appeared to be consistently expanded in PACAP KO embryos, and showed substantial spatial overlap with PAC1 gene expression (Fig. 7). Thus, quantitative measurements of the Pax6 domain were conducted in WT and PACAP KO embryos. These studies revealed slight, but significant increases in both total Pax6-positive area and lateral span of Pax6 expression in E12.5 PACAP KO spinal cords compared to WT spinal cords (Fig. 7D,F,G), whereas no differences were found in total area of spinal cord, or in the dorsal to ventral span of Pax6 expression (Fig. 7D,E,H). These results suggest that Pax6-immunostained area is expanded laterally in the E12.5 spinal cord of PACAP KO mice in vivo.

Figure 6. Immunofluorescence analysis of phenotypic markers and pattering molecules in spinal cords of embryonic day 12.5 wild type and PACAP KO mice.

Immunohistochemistry for Islet1/2, MNR2, Lim1/2, Pax6, Nkx2.2, Shh, and Neurofilament (165 kDa) were performed on WT and PACAP KO E12.5 embryonic spinal cords as indicated. Scale bar, 100 µm.

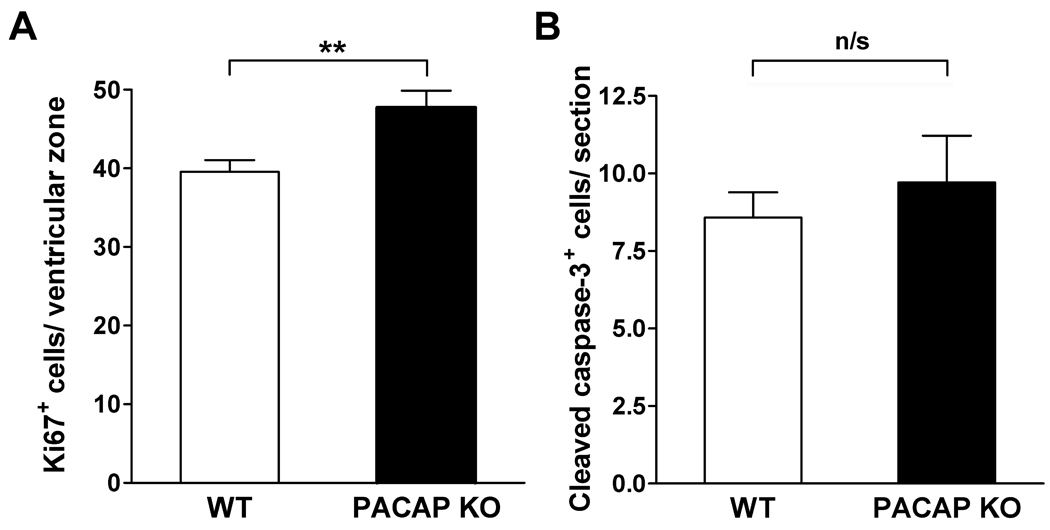

Loss of PACAP results in increased proliferation in the embryonic spinal cord ventricular zone, but has no effect on apoptosis

Our previous studies indicated that PACAP inhibited the proliferation of neural tube precursors cultured in 10% fetal calf serum and/or bFGF, but increased proliferation of these cells in the absence of serum or bFGF (Waschek et al., 1998; Lelievre et al., 2002), indicating that growth factors present in the microenvironment might modulate potential mitotic actions of PACAP on neural precursors in vivo. We therefore compared the numbers of proliferating cells in the spinal cords of WT vs. PACAP KO mice. Using Ki67 as a marker of proliferating cells, we detected a slightly, but significantly, higher numbers of Ki67 cells in PACAP KO embryonic spinal cord sections compared to their WT counterparts (Fig.8A). At the same time, we detected no difference in the number of cleaved caspase-3 positive apoptotic cells between WT and PACAP KO E12.5 spinal cords (Fig. 8B), suggesting that PACAP does not promote survival in the spinal cord at this stage of nervous system development, despite its well-documented anti-apoptotic effects in the postnatal cerebellum (Vaudry et al., 1999; Dejda et al., 2008; and reviewed in Botia et al., 2007), and its survival promoting actions on cultured embryonic rat motor neurons (Tomimatsu & Arakawa, 2008).

Figure 8. Cell proliferation is increased but apoptosis is unaffected in spinal cords of embryonic day 12.5 PACAP KO mice.

(A) Cell proliferation and (B) apoptosis in E12.5 spinal cords was analyzed by immunohistochemistry for Ki67 (WT: n=7, KO: n=5) and cleaved caspase-3 (WT: n=4, KO: n=4), respectively. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. n/s: non-significant, **p<0.01 vs. WT.

Discussion

Considerable evidence indicates that PKA antagonizes hedgehog-driven process, mainly by way of phosphorylation of Gli proteins (vertebrates) or cubitus interruptus (flies) (Milenkovic and Scott, 2010). These studies identify PACAP as a PKA-activating factor that can regulate the hedgehog-induced production of motor neurons in embryonic stem cell cultures via antagonism of the hedgehog signaling pathway. The clinical importance of identifying factors that can affect the production of motor neurons is well recognized. Motor neuron diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and spinal muscular dystrophy are highly debilitating diseases for which a cure has still not been discovered. Moreover, loss of motor neurons and/or motor neuron function severely limits recovery from spinal cord injury. Production of functional motor neurons from stem cells to replace the neurons lost in the course of these diseases has long been one of the primary goals of regenerative medicine, but so far the success of such therapies in animal models has been limited (Nayak et al., 2006). Understanding of the mechanisms involved in motor neuron differentiation from stem cells is considered to be a key to designing better cell replacement strategies for neurodegenerative diseases.

Motor neuron generation in vivo and in vitro

Various factors, including retinoic acid, Shh, fibroblast growth factors, and bone morphogenetic proteins have been implicated in the regulation of ventral spinal cord patterning and motor neuron specification (Briscoe & Ericson, 2001; Briscoe & Novitch, 2008). It has been shown that treatment of ES cell-derived EBs with retinoic acid and Shh induces ventral neural tube-like phenotypic differentiation and is sufficient to produce motor neurons in significant numbers (Wichterle et al., 2002). However, surprisingly little is known about how G-protein coupled receptor signaling can fine-tune the process of specification of various neuronal subtypes in the spinal cord. In this study we present evidence for the modulation by PACAP, a neuropeptide acting through G-protein coupled receptors, of Shh pathway- and retinoic acid-mediated ventral neuron specification in cultured EBs. In particular, we found that PACAP antagonizes the Shh agonist-stimulated emergence of ventral neural phenotypes in this culture system, as assayed by measuring the expression of ventral neural markers Nkx2.2, and Nkx6.1, as well as specific motor neuron markers HB9 and Islet2. We also found that PACAP prevented the direct activation of the Shh target gene Gli-1. Interestingly, it has been shown that both PACAP and its receptors are expressed in EBs generated from mouse ES cells (Cazillis et al., 2004; Hirose et al., 2005). Thus, although not examined here, it seems possible that blocking the action of endogenous PACAP in ES cell cultures systems might result in an even more efficient generation of motor neurons than with the combination of retinoic acid and Shh alone.

Motor neuron production and patterning in spinal cords of PACAP-deficient mice

The above results encouraged us to examine whether or not loss of PACAP would influence the neuronal phenotype and Shh signaling in the spinal cord in vivo. Thus we compared the pattern of ventral neuronal populations and phenotypic markers known influenced by Shh in WT and PACAP KO embryos. Loss of PACAP did not have an obvious effect on the expression patterns of Islet1/2, MNR2, Lim1/2, and Nkx2.2 in spinal cords of E12.5 embryos, but we cannot rule out subtle differences in expression levels between WT and PACAP KO embryos, which would be difficult to quantify using immunohistochemistry. Interestingly, the Pax6 domain was slightly expanded in the embryonic spinal cord, suggesting that PACAP normally restricts the domain of Pax6 expression.

PACAP has also been shown to promote neuronal survival in a variety of settings in vivo and in vitro, and to regulate the rate of proliferation of neural precursors (for review, Waschek, 2002). Interestingly, the effect of PACAP on proliferation can be either positive or negative, depending on the cell type and developmental stage (Lu & DiCicco-Bloom, 1997; Lu et al., 1998; Suh et al., 2001; Lelievre et al., 2002; Nicot et al., 2002). It was thus of interest to investigate if PACAP loss would affect neural proliferation in embryonic spinal cord. We found that there was a slight, but significant increase in the number of Ki67 positive cells in the ventricular zone of PACAP KO spinal cords at E12.5, suggesting either that PACAP promotes the differentiation of proliferating progenitors, or alternatively that it acts more directly to regulate the cell cycle, as demonstrated in the developing cortex by Carey et al. (2002). On the other hand, no differences were observed in the apoptosis in the spinal cord of PACAP KO vs. WT embryos. However, few apoptotic cells were detected in either genotype, suggesting that programmed cell death is quite limited in the spinal cord at this developmental stage.

Potential mechanisms to compensate for PACAP loss

The remarkable robustness of the nervous system development has been demonstrated by numerous gene knockout experiments and other approaches, so it was not altogether surprising that embryonic mice would seem relatively resistant to the loss of PACAP. One explanation for the lack of observable effect of PACAP loss on motor neuron production in vivo is that its loss was counteracted by one or more negative feedback loops within the Shh signaling pathway (Ho & Scott, 2002; Ruiz i Altaba et al., 2002a; Ruiz i Altaba et al., 2002b; Jiang, 2006). Other compensatory mechanisms operating in PACAP KO mice might involve VIP and/or any one of the receptors that bind these peptides: VPAC1, VPAC2, or PAC1. However, in a previous study, no observable increases in the expression of VIP or any of the VIP or PACAP receptors were observed in the developing brain of postnatal PACAP KO mice compared to WT animals (Girard et al., 2006). Thus, increased expression of VIP and/or PACAP or VIP receptors appears not to be a general compensatory mechanism for loss of PACAP. In addition to compensation by overexpression of VIP and/or VIP/PACAP receptors, we also considered an alternative compensatory mechanism involving decreased expression of the Shh ligand in PACAP KO embryos. However, we were not able to detect any differences in the pattern of expression of Shh between WT and PACAP KO embryos, suggesting that this mechanism is also not involved in neutralizing the effect of PACAP loss on spinal cord patterning.

It should be pointed out that PACAP deficiency in knockout animals often fails to produce developmental defects expected based on in vitro and in vivo studies of the effects of exogenous PACAP. For example, PACAP was reported to increase the number of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons in embryonic rat mesencephalic cultures (Takei et al., 1998). However lack of PACAP in the mouse did not change the immunoreactivities of tyrosine hydroxylase in the several embryonic brain regions and ventral spinal cord (Ogawa et al., 2005). Another well characterized developmental action of PACAP is its survival-promoting effects on cerebellar granule neurons and/or their precursors (Vaudry et al., 1999; reviewed in Botia et al., 2007). Interestingly, PACAP-deficiency or exogenously-administered PACAP modifies the early stages of postnatal cerebellar development (Allais et al., 2007; Vaudry et al., 1999), but by P11, the cerebellum of WT and PACAP KO mice is similar (Vaudry et al., 2005). It is therefore possible that at least some effects of endogenous PACAP in vivo are transient and that a more detailed analysis of spinal cord patterning at various developmental time points would reveal more obvious defects in PACAP-deficient animals.

Conclusions

We have used an embryonic stem cell/embryoid body approach to demonstrate a novel and robust action of PACAP to modulate the in vitro production of motor neurons, most likely occurring via direct inhibition of Shh signaling. Analyses of spinal cords of PACAP KO and WT mice at E12.5 on the other hand, showed no obvious differences in numbers or distributions of motor neurons or other ventral phenotypes. A subtle increase in proliferation but not apoptosis, and a slight expansion of Pax6-positive area was observed in mice lacking PACAP. The apparent lack of effect of PACAP deficiency on motor neurons and other phenotypes in the embryonic spinal cords might be explained by specific compensatory mechanisms that operate in these animals or by the general robustness of CNS development.

Acknowledgments

The work was funded by NIH grants HD06576, HD34475, and HD04612. We would like to thank Dr. Hynek Wichterle at Columbia University for providing HBG3 ES cell line.

Abbreviations

- PACAP

pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide

- Shh

Sonic hedgehog

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal peptide

- CNS

central nervous system

- E10.5

embryonic day 10.5

- ES cells

embryonic stem cells

- WT

wild-type

- KO

deficient

- EBs

embryoid bodies

- Hh

hedgehog

References

- Allais A, Burel D, Isaac ER, Gray SL, Basille M, Ravni A, Sherwood NM, Vaudry H, Gonzalez BJ. Altered cerebellar development in mice lacking pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:2604–2618. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura A. Perspectives on pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the neuroendocrine, endocrine, and nervous systems. Jpn J Physiol. 1998;48:301–331. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.48.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botia B, Basille M, Allais A, Raoult E, Falluel-Morel A, Galas L, Jolivel V, Wurtz O, Komuro H, Fournier A, Vaudry H, Burel D, Gonzalez BJ, Vaudry D. Neurotrophic effects of PACAP in the cerebellar cortex. Peptides. 2007;28:1746–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Ericson J. Specification of neuronal fates in the ventral neural tube. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Novitch BG. Regulatory pathways linking progenitor patterning, cell fates and neurogenesis in the ventral neural tube. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:57–70. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RG, Li B, DiCicco-Bloom E. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide anti-mitogenic signaling in cerebral cortical progenitors is regulated by p57Kip2-dependent CDK2 activity. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1583–1591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01583.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazillis M, Gonzalez BJ, Billardon C, Lombet A, Fraichard A, Samarut J, Gressens P, Vaudry H, Rostène W. VIP and PACAP induce selective neuronal differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:798–808. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2004.03138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell CS, Michel S, Itri J, Rodriguez W, Tam J, Lelièvre V, Hu Z, Waschek JA. Selective deficits in the circadian light response in mice lacking PACAP. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1194–R1201. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00268.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejda A, Jolivel V, Bourgault S, Seaborn T, Fournier A, Vaudry H, Vaudry D. Inhibitory effect of PACAP on caspase activity in neuronal apoptosis: a better understanding towards therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. J Mol Neurosci. 2008;36:26–37. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M, Pozo D, Ganea D. The significance of vasoactive intestinal peptide in immunomodulation. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:249–290. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessaud E, McMahon AP, Briscoe J. Pattern formation in the vertebrate neural tube: a sonic hedgehog morphogen-regulated transcriptional network. Development. 2008;135:2489–2503. doi: 10.1242/dev.009324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DJ, Marti E, Scott MP, McMahon AP. Antagonizing cAMP-dependent protein kinase A in the dorsal CNS activates a conserved Sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. Development. 1996;122:2885–2894. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson J, Morton S, Kawakami A, Roelink H, Jessell TM. Two critical periods of Sonic Hedgehog signaling required for the specification of motor neuron identity. Cell. 1996;87:661–673. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson J, Rashbass P, Schedl A, Brenner-Morton S, Kawakami A, van Heyningen V, Jessell TM, Briscoe J. Pax6 controls progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in response to graded Shh signaling. Cell. 1997;90:169–180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuss B, Wintergerst ES, Bartsch U, Schachner M. Molecular characterization and in situ mRNA localization of the neural recognition molecule J1-160/180: a modular structure similar to tenascin. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:1237–1249. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.5.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard BA, Lelievre V, Braas KM, Razinia T, Vizzard MA, Ioffe Y, El Meskini R, Ronnett GV, Waschek JA, May V. Noncompensation in peptide/receptor gene expression and distinct behavioral phenotypes in VIP- and PACAP-deficient mice. J Neurochem. 2006;99:499–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt M, Bitgood MJ, McMahon AP. Protein kinase A is a common negative regulator of Hedgehog signaling in the vertebrate embryo. Genes Dev. 1996;10:647–658. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose M, Hashimoto H, Shintani N, Nakanishi M, Arakawa N, Iga J, Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Baba A. Differential expression of mRNAs for PACAP and its receptors during neural differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Regul Pept. 2005;126:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho KS, Scott MP. Sonic hedgehog in the nervous system: functions, modifications and mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J. Regulation of Hh/Gli signaling by dual ubiquitin pathways. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2457–2463. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.21.3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelievre V, Hu Z, Byun JY, Ioffe Y, Waschek JA. Fibroblast growth factor-2 converts PACAP growth action on embryonic hindbrain precursors from stimulation to inhibition. J Neurosci Res. 2002;67:566–573. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelievre V, Seksenyan A, Nobuta H, Yong WH, Chhith S, Niewiadomski P, Cohen JR, Dong H, Flores A, Liau LM, Kornblum HI, Scott MP, Waschek JA. Disruption of the PACAP gene promotes medulloblastoma in ptc1 mutant mice. Dev Biol. 2008;313:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Ohlmeyer JT, Lane ME, Kalderon D. Function of protein kinase A in hedgehog signal transduction and Drosophila imaginal disc development. Cell. 1995;80:553–562. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90509-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu N, DiCicco-Bloom E. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide is an autocrine inhibitor of mitosis in cultured cortical precursor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3357–3362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu N, Zhou R, DiCicco-Bloom E. Opposing mitogenic regulation by PACAP in sympathetic and cerebral cortical precursors correlates with differential expression of PACAP receptor (PAC1-R) isoforms. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53:651–662. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980915)53:6<651::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martí E, Bumcrot DA, Takada R, McMahon AP. Requirement of 19K form of Sonic hedgehog for induction of distinct ventral cell types in CNS explants. Nature. 1995;375:322–325. doi: 10.1038/375322a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic L, Scott MP. Not lost in space: trafficking in the hedgehog signaling pathway. Science Signaling. 2010;3:pe14. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3117pe14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles GB, Yohn DC, Wichterle H, Jessell TM, Rafuse VF, Brownstone RM. Functional properties of motoneurons derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7848–7858. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1972-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak MS, Kim YS, Goldman M, Keirstead HS, Kerr DA. Cellular therapies in motor neuron diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:1128–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicot A, DiCicco-Bloom E. Regulation of neuroblast mitosis is determined by PACAP receptor isoform expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4758–4763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071465398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicot A, Lelièvre V, Tam J, Waschek JA, DiCicco-Bloom E. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and sonic hedgehog interact to control cerebellar granule precursor cell proliferation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9244–9254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09244.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T, Nakamachi T, Ohtaki H, Hashimoto H, Shintani N, Baba A, Watanabe J, Kikuyama S, Shioda S. Monoaminergic neuronal development is not affected in PACAP-gene-deficient mice. Regul Pept. 2005;126:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D, Rubin GM. cAMP-dependent protein kinase and hedgehog act antagonistically in regulating decapentaplegic transcription in Drosophila imaginal discs. Cell. 1995;80:543–552. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90508-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelink H, Porter JA, Chiang C, Tanabe Y, Chang DT, Beachy PA, Jessell TM. Floor plate and motor neuron induction by different concentrations of the amino-terminal cleavage product of sonic hedgehog autoproteolysis. Cell. 1995;81:445–455. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz i Altaba A, Palma V, Dahmane N. Hedgehog-Gli signalling and the growth of the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002a;3:24–33. doi: 10.1038/nrn704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz i Altaba A, Sánchez P, Dahmane N. Gli and hedgehog in cancer: tumours, embryos and stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002b;2:361–372. doi: 10.1038/nrc796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander M, Paydar S, Ericson J, Briscoe J, Berber E, German M, Jessell TM, Rubenstein JL. Ventral neural patterning by Nkx homeobox genes: Nkx6.1 controls somatic motor neuron and ventral interneuron fates. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2134–2139. doi: 10.1101/gad.820400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood NM, Krueckl SL, McRory JE. The origin and function of the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)/glucagon superfamily. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:619–670. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.6.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheward WJ, Lutz EM, Copp AJ, Harmar AJ. Expression of PACAP, and PACAP type 1 (PAC1) receptor mRNA during development of the mouse embryo. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;109:245–253. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D, Rosenthal A. Achieving neuronal patterning by repression. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:967–969. doi: 10.1038/79894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh J, Lu N, Nicot A, Tatsuno I, DiCicco-Bloom E. PACAP is an anti-mitogenic signal in developing cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:123–124. doi: 10.1038/83936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei N, Skoglösa Y, Lindholm D. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) on mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci Res. 1998;54:698–706. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981201)54:5<698::AID-JNR15>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe Y, Roelink H, Jessell TM. Induction of motor neurons by Sonic hedgehog is independent of floor plate differentiation. Curr Biol. 1995;5:651–658. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe Y, William C, Jessell TM. Specification of motor neuron identity by the MNR2 homeodomain protein. Cell. 1998;95:67–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81783-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomimatsu N, Arakawa Y. Survival-promoting activity of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide in the presence of phosphodiesterase inhibitors on rat motoneurons in culture: cAMP-protein kinase A-mediated survival. J Neurochem. 2008;107:628–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida T, Ensini M, Morton SB, Baldassare M, Edlund T, Jessell TM, Pfaff SL. Topographic organization of embryonic motor neurons defined by expression of LIM homeobox genes. Cell. 1994;79:957–970. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudry D, Gonzalez BJ, Basille M, Fournier A, Vaudry H. Neurotrophic activity of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide on rat cerebellar cortex during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9415–9420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudry D, Gonzalez BJ, Basille M, Yon L, Fournier A, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: from structure to functions. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:269–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudry D, Hamelink C, Damadzic R, Eskay RL, Gonzalez B, Eiden LE. Endogenous PACAP acts as a stress response peptide to protect cerebellar neurons from ethanol or oxidative insult. Peptides. 2005;26:2518–2524. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschek JA. VIP and PACAP receptor-mediated actions on cell proliferation and survival. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;805:290–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb17491.x. discussion 300–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschek JA, Casillas RA, Nguyen TB, DiCicco-Bloom EM, Carpenter EM, Rodriguez WI. Neural tube expression of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) and receptor: potential role in patterning and neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9602–9607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschek JA. Multiple actions of pituitary adenylyl cyclase activating peptide in nervous system development and regeneration. Dev Neurosci. 2002;24:14–23. doi: 10.1159/000064942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe J, Nakamachi T, Matsuno R, Hayashi D, Nakamura M, Kikuyama S, Nakajo S, Shioda S. Localization, characterization and function of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide during brain development. Peptides. 2007;28:1713–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle H, Lieberam I, Porter JA, Jessell TM. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into motor neurons. Cell. 2002;110:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]