Abstract

Cisplatin is a potent anti-cancer drug, which functions by cross-linking adjacent DNA guanine residues. However within one day of injection, 65~98% of the platinum in the blood plasma is protein-bound. It is generally accepted that cisplatin binds to methionine and histidine residues, but what is often underappreciated is that platinum from cisplatin has a 2+ charge and can form up to four bonds. Thus, it has the potential to function as a cross-linker. In this report, the cross-linking ability of cisplatin is demonstrated by Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FTICR) mass spectrometry (MS) with the use of standard peptides, the 16.8 kDa protein calmodulin (CaM), but was unsuccessful for the 64 kDa protein hemoglobin. The high resolution and mass accuracy of FTICR MS along with the high degree of fragmentation of large peptides afforded by collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) and electron capture dissociation (ECD) are shown to be a valuable means of characterizing cross-linking sites. Cisplatin is different from current cross-linking reagents by targeting new functional groups, thioethers, and imidazoles groups, which provides complementarity with existing cross-linkers. In addition, platinum(II) inherently has two positive charges which enhance the detection of cross-linked products. Higher charge states not only promote the detection of cross-linking products with less purification, but result in more comprehensive MS/MS fragmentation and can assist the assignment of modification sites. Moreover, the unique isotopic pattern of platinum flags cross-linking products and modification sites by mass spectrometry.

INTRODUCTION

High-throughput proteomics now enables the assignment of hundreds to thousands of proteins in a single experiment; however, the physiological function of many newly discovered proteins remains unclear. It has become evident that proteins often carry out their function as part of large complexes, and their interaction is the core of cellular function.1 Therefore, the determination of a protein’s three dimensional structure and the identification of its interaction partners are critical next steps in understanding protein action. Many techniques have been developed to probe protein-protein interactions, such as X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, which provide high resolution structural information, but these methods require a relatively large amount of pure protein; alternatively, the chemical cross-linking approach allows low resolution structural data to be generated by covalently joining pairs of functional groups within a protein or a protein complex. The covalent bonds formed by cross-linking can stabilize or freeze labile interactions. Thus the distance constraints created between the reactive groups can help define 3-D structures of proteins or protein complexes.2 Moreover, the combination of cross-linking with mass spectrometry (MS) has facilitated the investigation of protein-protein interactions due to its high sensitivity, fast speed of analysis, reliable sequence identification, and theoretically unlimited mass range.2–7 Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FTICR) mass spectrometry has been proved to be an potent tool for analyzing cross-linking reaction mixtures. The high mass accuracy of FTICR MS can greatly reduce the number of candidates for cross-linking products, and in addition, its high resolution, the ability of allowing a “gas phase” purification to accumulate low intensity cross-linking product ions, and the ability to fragment large proteins or peptides extensively are critical for the unambiguous assignment of the cross-linking products and localization of the cross-linking sites. However, the identification of the cross-linked products can be still quite difficult due to the complexity of reaction mixtures. The cross-linking chemistry inevitably produces a variety of products, including unmodified peptides, multiply modified peptides, dead-end, intra- and inter-peptide cross-linking products all present in the same sample, which makes the detection and identification of low-abundance cross-linked products challenging. To overcome these challenges, significant effort has been dedicated to design new cross-linkers which can enrich cross-linked products via affinity tags,8–10 or facilitate the identification of cross-linked products by introducing mass spectrometry-cleavable bonds6–7 or specific signature patterns,10–13 such as PIR (protein interaction reporter),7 isotope-labeled cross-linkers11–12 or isotope-labeled proteins.13

Although there is a broad range of cross-linking reagents available, they all target a few particular functional groups, generally primary amines, carboxylates, sulfhydryls, and free carbonyls (aldehyde groups generated via protein oxidation).14 The limited choices of reactive groups have limited the application of cross-linking; moreover, some of the inherent chemical problems of existing functional groups also hinder the interpretation of cross-linking data. For example, the complexity of the reaction mixtures makes assignment difficult, and low charge states but high mass-to-charge (m/z) ions are often formed upon electrospray ionization when the cross-linking reagent reacts with primary amine groups of lysines and the amino terminus, which could otherwise carry a charge. Therefore, the development of MS identifiable cross-linkers which target new functional groups will be of benefit in the mapping of protein-protein interactions.

Cisplatin, cis-[Pt(NH3)2Cl2], is a widely used anticancer drug which exerts its cytotoxic effect by reacting with DNA and forms 1,2- intrastrand cross-links between adjacent guanines.15 The DNA cross-linking ability of cisplatin and its analogs have been well documented.15–18 In addition, a new class of anticancer drugs with multinuclear platinum molecules linked by flexible arms is capable of forming long range inter- or intrastand cross-links.19–21 A few studies have demonstrated the ability of platinum compounds to cross-link DNA with proteins.22–24 However, up to 98% of the platinum in the blood plasma is protein-bound within one day of injection.25 The binding of cisplatin to proteins is likely to be a primary cause of the side effects of such chemotherapies. However, the interactions of proteins with platinum compounds have not been extensively explored compared to DNA-Pt research.

The ability of a platinum complex to cross-link proteins has been unexpectedly observed by Guo et al., and their result shows that cisplatin can stabilize a multimeric complex of the human Ctr1 copper transporter by cross-linking adjacent proteins via methinone binding.26 Recently, Hu et al. also found that cisplatin cross-links domains of albumin.27 However, whether cisplatin can function as a cross-linking reagent has not been fully explored. Platinum(II) has a strong affinity for sulfur and nitrogen containing ligands, and the coordination sites are the side chains of methionine (Met), cysteine (Cys) and histidine (His), namely, thioether, sulfhydryl, and imidazole.28 Thus, cross-linkers targeting these functional groups will broaden the application of cross-linking and contribute to the understanding of protein action. Here, the ability of cisplatin as a potential cross-linker is explored and demonstrated using standard peptides and the 16.8 kDa protein calmodulin (CaM), but was unsuccessfully tested with the 64 kDa protein hemoglobin. In addition, the features of cisplatin as a potential cross-linking reagent are discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Materials

Angiotensin II, bombesin, bovine calmodulin (CaM), trypsin, ammonium acetate (CH3COONH4), and ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). HPLC grade methanol, acetic acid (HAc), and acetonitrile (ACN) were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Cisplatin was synthesized and characterized by standard methods.29

Reaction of peptides with Cisplatin

Aqueous solutions of 1000 μM angiotensin II, 1000 μM bombesin, and 500 μM cisplatin were prepared and mixed to give 200 μL of an angiotensin II:bombesin:platinum complex solution at a molar concentration of 20 μM and a molar ratio of 1:1:3. The sample was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, the pH value was determined before and after the reaction, both were 6. The sample was diluted to 0.4 μM with 50% MeOH-1% CH3COOH buffer immediately before mass spectrometry analysis.

Reaction of Proteins with Cisplatin and Digestion of CaM-cisplatin Adducts

Five hundred micromolar aqueous solutions of CaM and 500 μM cisplatin were mixed and diluted with water to give a 200 μL (40 μM) solution of protein:platinum complex at a molar ratio of 1:1. The sample was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and then centrifuged using Amicon filters (MW cut off = 3 kDa, Millipore, Watford, UK) at 13000 rpm (14857×g) for 30 min at room temperature, to remove unbound platinum complex, and washed twice with 200 μL water. Samples were then diluted to 0.4 μM immediately before for MS analysis. Aqueous solutions of hemoglobin (500 μM) and cisplatin were reacted at a molar ratio of 1:5 and treated in the same manner as above.

The CaM-platinum adducts in the 1:1 CaM-cisplatin mixture were diluted to 20 μM with 50 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 7.8) and then subjected to trypsin digestion at a protein to enzyme ratio of 40:1 (w/w) at 37 °C for 4 h. As a control, 20 μM free CaM was digested under the same conditions. Immediately before ESI-MS analysis, the digest solution was diluted to 0.4 μM with 50% MeOH-1% CH3COOH buffer.

FT ICR Mass Spectrometry

ESI-MS was performed on a Bruker SolariX FT ICR mass spectrometer with an ESI source and a 12T actively shielded magnet. Samples are electrosprayed at 0.4 μM concentration in 50:50 MeOH:H2O with 1% acetic acid. For collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) experiments, the parent ions were isolated using the first quadrupole (Q1), and were fragmented in the collision cell (q, typical collision energies ~10–25 eV), and then transmitted into the ICR cell for detection. For electron capture dissociation (ECD) experiments, the parent ions were isolated in Q1 and externally accumulated in collision cell for 3–10 s. After being transferred and trapped in the Infinity ICR cell,30 ions were irradiated with 1.5 eV electrons from a 1.7 A heated hollow cathode dispenser for 50 to 80 ms. Full spectra were internally calibrated using peptide (bombesin or digested CaM) peaks, CAD spectra were internally calibrated using known b ion masses of bombesin or y ion masses of CaM(37–74), ECD spectra were internally calibrated using known c ion masses of bombesin or c ion masses of CaM(107–126). The assigned mass tables for each spectrum are provided as supplementary information (Tables S2~S8).

RESULTS

Intermolecular cross-linking of peptides

Angiotensin II and bombesin are small peptides both with potential histidine or methionine platinum binding sites; their amino acid sequences are shown in Table S-1. Initial experiments showed that His12 of bombesin and His6 of angiotensin II are the binding sites for platinum (Figure S-1); in addition, platinum was also found to bind to the carboxyl group of N-terminal aspartic acid (Asp) residue in angiotensin II (a1+Pt ion in Figure S-1a).31–32 We therefore chose these two peptides for the cross-linking studies.

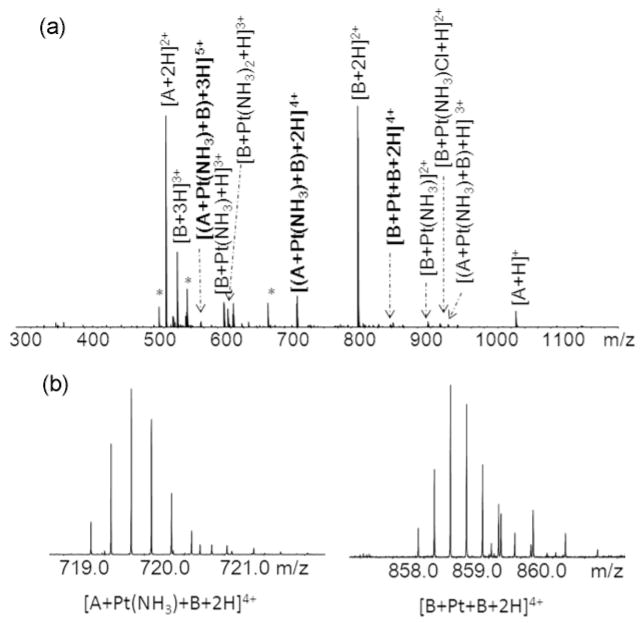

Platinum(II) is normally square planar with four covalent bonds. Depending on the type and number of nucleophiles available and steric accessibility of peptides or proteins, all the ligands of cisplatin can also be substituted by nucleophilic species.33–35 As shown in Figure 1a, in additional to the various peptide-Pt adducts, two multiply charged ions at m/z 719.8 (4+) and m/z 858.9 (4+) were detected (Figure 1b). The m/z 719.8 (4+) value matches the mass of angiotensin II plus the mass of bombesin and plus Pt(NH3) (m/z 719.83924, −0.10 ppm), the m/z 858.9 (4+) value is consistent with the masses of two molecular bombesin plus a Pt (m/z 858.90300, 0.17 ppm). To simplify the labeling of the mass spectrum of angiotensin- bombesin-cisplatin mixture, angiotensin and bombesin are abbreviated by their initials as A and B, respectively. The ions at m/z 719.8 and m/z 858.9 have isotopic distributions of that both match their theoretical isotopic distributions of [A+ Pt(NH3)+B+2H]4+ and [B+Pt+B+2H]4+ ions with mean absolute deviation 0.37 ppm (Table S-2), which implies that platinum(II) can cross-link peptides intermolecularly.

Figure 1.

(a) Mass spectrum of angiotensin II-bombesin-cisplatin (1:1:3) mixture. (b) Isotopic distributions of the cross-linking products [A+Pt(NH3)+B+2H]4+ and [B+Pt+B+2H]4+ ions. Peaks labeled with * are chemical noise. Peak results are listed in Table S-2.

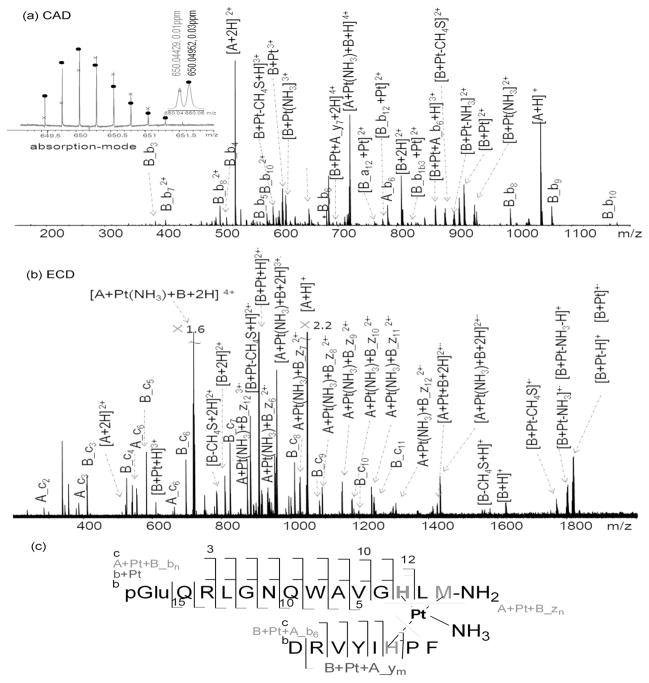

Collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) and electron capture dissociation (ECD) experiments were both performed to locate the cross-linking sites. To label the sources of b/y and c/z ions, b/y and c/z ions from bombesin (B) are labeled as B_bn, B_ym, B_cn, and B_zm; similarly, b/y and c/z ions from angiotensin II (A) are labeled as A_bn, A_ym, A_cn, and A_zm. Figure 2a shows the CAD spectrum of the [A+ Pt(NH3)+B+2H]4+ ion at m/z 719.8. Table S-3 shows the assignments of each product ion peak of [A+ Pt(NH3)+B+2H]4+ ion with mean absolute deviation 0.29 ppm, which yields high confidence in each product peak assignment. The detection of B_b3 to B_b10 ions, B_b7 2+ to B_b11 2+ ions without platinum, and (B_b12+Pt)2+ to (B_b13+Pt)2+ ions indicates that platinum binds to His12. Also, ions at m/z 649.8 were found to have overlapping isotopic distributions of [A+ Pt+B_b12+2H]4+ ion and [B+Pt+A_b6+2H]4+ ion (insert of Figure 2a), indicating that platinum cross-links His6 of angiotensin II and His12 of bombesin. The observation of [B+Pt(NH3)+A_y7+2H]4+ also indicates that His6 rather than of Asp1 of angiotensin II is primarily involved in the cross-linking. The mass spectrometry (MS) data ranging from m/z 649 to m/z 652 were processed with phase correction to yield the Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) absorption mode spectrum which improves the peak shape and resolution as shown in the insert of Figure 2a.36 Platinum(II) has a total of four coordination sites; one amine (NH3), His6 of angiotensin II and His12 of bombesin occupy three of the binding sites. Therefore, one more binding site needs to be assigned. The [B+Pt-CH4S]2+ ion peak was found with a deviation of −0.18 ppm (−0.16 mDa) from the calculated mass, suggesting that platinum binds to the sulfur of the Met14 of bombesin. Literature would suggest that loss of CH4S directly from MS/MS cleavage of the side chain of methinone is a minor fragmentation chanel,37 but it is possible that the presence of cisplatin has changed the local chemical environment to promote the reaction. In order to test whether the loss of CH4S arises from the coordination of Met to platinum rather than direct loss of CH4S from bombesin, different charge states of bombesin ions, the [B+2H]2+ ions and [B+3H]3+ ions were dissociated. No [B+2H-CH4S]2+ ion was detected in either of the CAD spectra of the [B+2H]2+ ions or [B+3H]3+ ions (Figure S-2), which agrees with the hypothesis that platinum coordinates to the sulfur of the Met14 of bombesin (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

(a) CAD-MS2 spectrum of the cross-linking product [A+Pt(NH3)+B+2H] 4+ ion at m/z 719.34. Insert is the overlapping isotopic distributions of [A+Pt+B_b12+2H]4+ (cross) and B+Pt+A_b6+2H]4+ (circle) ions in absorption mode. (b) ECD-MS2 spectrum [A+Pt(NH3)+B+2H] 4+ ion at m/z 719.34. Peak results are listed in Table S-3 (CAD) and Table S-4 (ECD). (c) Fragmentation diagram of the cross-linking product A+Pt(NH3)+B.

Although ECD has been reported to be problematic on Pt-bound proteins,38 an ECD experiment was still tested in an effort to further localize the cross-linking sites. The observation of B_c3 to B_c11 ions, A_c2 to A_c5 ions, A+Pt+B_z5 2+· to A+Pt+B_z15 2+· ions, and the [B-CH4S+H]+ ion were all consistent with the CAD results, that is, Pt not only cross-links His6 of angiotensin II and His12 of bombesin, but also macrochelates His12 and Met14 of bombesin (Figure 2c). The macrochelation of Pt with methionine (S) and histidine (N) (κ2SM, NH) coordination result agrees with Gibson’s and Hohage’s results,31, 39 in which they showed that the macrochelates with κ2SM, NH coordination modes are favorable in weakly acidic solutions (3≤pH≤6).

In the same sample, bombesin was also detected to cross-link with another bombesin molecule. Figure S-3a shows the CAD spectrum of the [B+Pt+B+2H]4+ ion at m/z 858.9. Similar diagnostic ions, like [B_b12+Pt]2+, [B+Pt+B_b12]2+, [B+Pt+B_b13]2+, and [B+Pt-CH4S]2+ ions, were detected, indicating that platinum cross-links two bombesin molecules by binding to the His and Met residues of bombesin. The ECD results are also in agreement with the CAD data, as shown in Figure S-3b; the observation of B_c3 ions to B_c11 ions indicates that His12 and/or Met14 are the binding sites. As platinum cross-links two peptides with the same sequence, B_c3 ions to B_c11 ions can be generated from either chain, namely, the cross-linking sites are localized at His12 and Met14 sites of each chain. Compared to the CAD and ECD spectra of the [A+ Pt(NH3)+B+2H]4+ ion, many fewer peaks were observed in the CAD and ECD spectra of the [B+Pt+B+2H]4+ ion (peak lists are available in Table S-5 and Table S-6), which is likely to be due to the symmetric structure after platinum binding, as shown in Figure S-3c.

Intramolecular cross-linking of Calmodulin

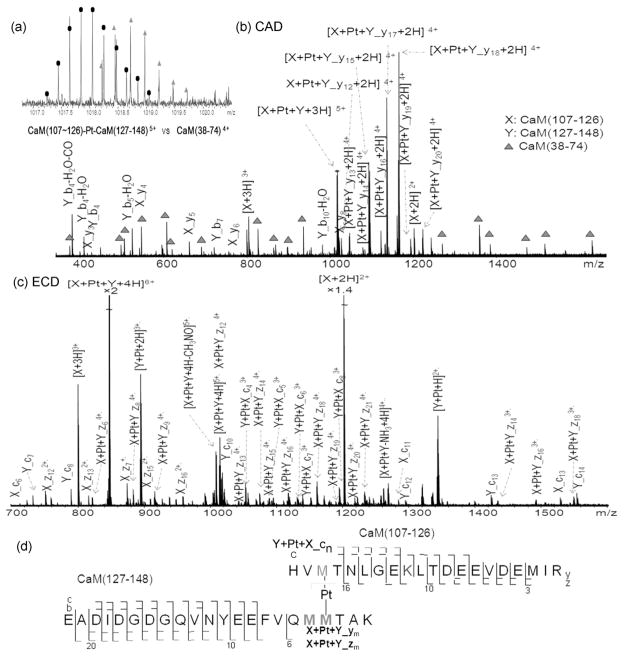

Calmodulin (CaM) is a small 16.8 kDa acidic protein, containing 9 Met residues out of 148 amino acid residues (Table S-1). The Met residues in CaM play an important role in its versatility, and contribute as much as 46% of the exposed surface area of the hydrophobic patches on the calmodulin surface,40 which makes CaM an interesting target for this cross-linking study. CaM and cisplatin were incubated in a 1:1 mixture at 37 °C in water for 24 hours, and then subjected to trypsin digestion at a CaM-cisplatin to enzyme ratio of 40:1 (w/w) at 37 °C for 4 h followed by ESI-FTMS analysis. In addition to the peaks which correlate with Pt binding to the tryptic digested peptides, a peak corresponding to the platinum cross-linked tryptic digest peptides CaM(107–126) and CaM(127–148) was observed at m/z 1018 (5+) with a mass error of −0.08 ppm, as shown in Figure 3a, which is overlapped with the 4+ charge state CaM(38–74) ion.

Figure 3.

(a) Cross-linking product spectrum from the digested CaM-cisplatin (1:1) mixture. The theoretical isotopic distribution of the cross-linking product CaM(107–126)-Pt-CaM(127–148)5+ ion (circles)which is overlapped with the digested peptide CaM(38–74)4+ ion (triangles). (b) CAD-MS2 spectrum of the cross-linking product CaM(107~126)+Pt+CaM(127–148)5+ ion at m/z 1018. (c) ECD-MS2 spectrum of the cross-linking product CaM(107~126)+Pt+CaM(127–148)6+ ion at m/z 848. (d) (c) Fragmentation diagram of the cross-linking product CaM(107~126)+Pt+CaM(127–148). For the full peak list, see Table S-7 (CAD) and Table S-8 (ECD).

Figure 3a shows the two overlapped experimental isotopic distributions and the theoretical isotopic distributions (see figure legend), clearly demonstrating the resolving power of the FTICR MS instrument used. Despite the fact that CaM(107–126) and CaM(127–148) are contiguous tryptic peptides within native calmodulin, these are not missed tryptic cleavages as shown in the MS/MS experiment discussed below. The [CaM(107–126)+Pt+CaM(127–148)+3H]5+ ion was isolated by the front-end quadrupole (Q) with an isolation window of ±5 Da and then fragmented in the collision cell (q). Therefore, because of the overlap, the [CaM(38–74)+2H]4+ ion was also isolated and fragmented at the same time. To simplify the labeling of the product ion spectrum of the [CaM(107–126)+Pt+CaM(127–148)+3H]5+ ion (Figure 3), CaM(107–126), CaM(127–148) and CaM(38–74) are assigned as X, Y, and Z, respectively. The observation of X_y3 to X-y6 ions from CaM(107–126) and Y_b3-H2O to Y_b7-H2O ions from CaM(127–148) show that the linkage between CaM126 and CaM127 has been cleaved during trypsin digestion, which proves the existence of cross-linking rather than platinum binding to a missed cleavage peptide and a dehydrated CaM(107–148) species. A series of [X+Pt+Y_y12+2H]4+ to [X+Pt+Y_y20+2H]4+ ions, further confirms that these two peptides are cross-linked by platinum, and also suggests that platinum binds to the C-terminal Met144 or Met145 residue of CaM(127–148). In addition, the detection of a series of X_y3 to X_y8 ions indicates that platinum coordinates to the N-terminal Met109 site (Figure 3d). ECD experiments were performed on both the [CaM(107–126)+Pt+CaM(127–148)+3H]5+ ion and the [CaM(107–126)+Pt+CaM(127–148)+4H]6+ ion, the ECD spectrum of the [CaM(107–126)+Pt+CaM(127–148)+4H]6+ ion at m/z 848 were chosen and shown in Figure 3c. The observation of Y_c3 to Y_c14 ions, X+Pt+Y_z6 ion, and X+Pt+Y_z8 to X+Pt+Y_z21 ions all indicates that platinum coordinates to either/both Met144 and Met145 sites, rather than carboxyl groups (D or E) in the CaM(127–148) chain. Similarly, the detection of the Y+Pt+X_c4 to Y+Pt+X_c8 ion series correlates with the CAD result, that platinum binds to the Met109 site of CaM(107–126). It is generally accepted that ECD fragmentation preserves labile modification sites;41 however, the observation of single chain ions like [X+2H]2+ and [X+3H]3+ ions (Figure 3c), [A+H]+ and [B+2H]2+ ions (Figure 2b & Figure S-3b) implies that ECD may fragment the labile modification sites (Pt-N or Pt-S) in this specific Pt-bound peptide. Therefore, the origin of X_c4 to X_c13 ions can either be from the cross-linked precursor ions or it can, more likely, originate from the [X+2H]2+ or [X+3H]3+ ions by secondary electron capture rather than from the precursor ions. As shown in Figure 3c, for the X (CaM(107–126)) chain, intense [X+2H]2+ and [X+3H]3+ peaks were observed; for the Y (CaM(127–148)) chain, platinum-bound peaks [Y+Pt+2H]3+· and [Y+Pt+H]2+· were detected, and no single Y chain ions or Y_c/z ions at the platinum bound region appeared, all these results support the hypothesis that the X_c4 to X_c13 ions were generated by secondary electron capture. Furthermore, the detection of [X+2H]2+, [X+3H]3+, [Y+Pt+2H]3+·, and [Y+Pt+H]2+· ions indicates that the Pt-Y chain is more strongly bound than the X-Pt chain under ECD conditions. Therefore, it is likely that platinum coordinates to the Met109 of CaM(107–126) and Met144 or Met145 of CaM(127–148) by forming stable six-membered κ2SM, NM chelates on the respective residues.42–43

An interesting phenomenon of cisplatin cross-links in calmodulin is that all the ligands of cisplatin are displaced, which rarely happens in cisplatin-DNA adducts.44–45 Similar results have also been observed in other Met-rich peptides or proteins upon reaction with cisplatin due to the trans-labilization effect.33–35 In other words, once the displacement of chlorine by sulfur of at Met or Cys residue has occurred, the Pt-NH3 bond trans to the sulfur is significantly labilized and thus the amine group is readily substituted.

Intermolecular cross-linking of protein

Hemoglobin is a tetrameric heme-protein in the red cells of the blood in mammals and other animals; it contains two alpha and two beta subunits non-covalently bound, designated as α2β2. Each subunit has multiple potential platinum binding sites, as listed in Table S-1, the α unit has two Met, ten His, and one Cys residue; the β unit has one Met, nine His and two Cys residues. Since hemoglobin is a well understood and easy to obtain protein, it was therefore of interest to investigate whether cisplatin can cross-link α and β subunits. Although the study of cisplatin-hemoglobin has been reported,46 whether cisplain can cross-link hemoglobin complex subunits has not been explored.

Abundant α and β peaks along with peaks corresponding to platinum bound to either α or β subunits were detected (Figure S-4); however, no peaks corresponding to cisplatin cross-linking between the α and β subunits were detected.

DISCUSSION

The cross-linking sites were identified and localized by FTICR MS because of its unsurpassed resolution and mass accuracy, and also its ability to extensively fragment large peptides by CAD and ECD fragmentation techniques. Sub-ppm mass accuracy is routinely achieved by SolariX FTICR MS (Table S-2 to Table S-9) which is critical for the assignment of all the peaks as the number of peptides with the same nominal mass but different amino acid sequence increases dramatically with the number of amino acid residues in the peptides.5 In the case of the overlapping peaks [A+Pt+B_b12+2H]4+ at m/z 650.04429 and [B+Pt+A_b6+2H]4+ at m/z 650.04952 (the insert of Figure 2a), the mass difference between these two peaks is only 5.2 mDa; therefore, the high resolution (R=200,000) and mass accuracy (0.03 ppm) of this spectrum greatly aid the assignments of these two peaks. More importantly, the assignment of these two peaks is critical for localizing the cross-linking sites.

Although the above experiments and CAD and ECD data all show that cisplatin has the potential to be a peptide and protein cross-linker, in the development of a cross-linker, there are multiple characteristics that should be considered, such as chemical specificity, arm length, water solubility and cell membrane permeability, homobifunctional or heterobifunctional reactive groups, and cleavability.14 In light of these considerations, the potential for cisplatin as a cross-linker is discussed below.

Chemical specificity

Although there are 20 different amino acids in protein structures, only a small number of protein functional groups comprise selectable targets for practical cross-linking studies. In practice, only four protein functional groups (primary amines, carboxylates, sulfhydryls, and carbonyls) account for the vast majority of cross-linking and chemical modification sites. However, there are up to nine amino acids in proteins that are readily derivatizable at their side chains, including aspartic acid, glutamic acid, lysine, arginine, cysteine, histidine, tyrosine, methionine, and tryptophan. These nine residues contain eight principal functional groups, in addition to primary amines, carboxylates, and sulfhydryls (or disulfides), thioethers, imidazoles, guanidinyl groups, phenolic and indolyl rings also have sufficient reactivity for modification reactions.14

Platinum(II) has a strong affinity for sulfur and nitrogen containing ligands, such as methionine, cysteine, and histidine. As shown by the data obtained here, platinum can coordinate to both histidine and methionine, providing new functional groups for cross-linking. The discovery of new cross-linkers targeting new reactive groups will facilitate the analysis of the three-dimensional structures of proteins and the identification of interaction partners. Moreover, new cross-linkers can help to overcome the inherent problems of existing reactive groups, such as primary amines.2 Although the primary amine is by far the most commonly targeted functional group, there are several limitations. First, cross-linkers react with primary amine groups of lysine residues and the N-terminal of proteins, and trypsin cannot normally cleave C-terminal to a modified lysine residue; therefore, larger peptides are generated from such cross-linked proteins during enzymatic proteolysis due to missed cleavages. Platinum reacts with histidine, methionine, and cysteine, which can easily overcome this problem. Second, the modification of the amine group of lysine leads to a loss of a positively-charged site. Thus, digested cross-linked peptide ions with lower charge states are created during electrospray ionization, reducing sensitivity and MS/MS performance.

Compatibility with Mass Spectrometry

(1) Inherent two positive charges of Pt(II)

On one hand, platinum does not result in charge loss; on the other hand, platinum inherently has two positive charges, e.g. when the fragment {Pt(NH3)2}2+ binds, the cross-linking products observed often have higher charge states than the peptides or proteins alone. Higher charge states not only promote the detection of cross-linking products without purification, but also result in a more comprehensive MS/MS fragmentation pattern and therefore assist in the identification of modification sites.

(2) Unique isotopic pattern

Challenges to identify cross-linked products by mass spectrometry have arisen due to the complexity of the cross-linking reaction mixtures and low abundance of the cross-linked species. As presented in Figure 1, predominantly unmodified peptides, dead-end modified peptides, and a low abundance of inter-cross-linked peptides were detected. To overcome the challenges, significant effort has been made to develop new cross-linkers to facilitate the identification of cross-linked species by introducing a signature pattern in the data via isotope-labeling, such as isotope labeling the cross-linking reagents or proteins,11–13 proteolytic digestion in 18O labeling water,10 or by enriching cross-linked products, such as affinity tags.7–10 In many cross-linking applications, isotope labeling has greatly facilitated the identification of cross-linked products. However, frequently, isotope labeling complicates the mass spectra of products, increases the possibility of peak overlap, and lowers the possibility of cross-linked products being detected by mass spectrometry due to ion suppression effects. In addition, incomplete labeling, for example due to partial label 18O exchange in proteolytic digestion samples, distorts the natural isotopic distribution.47 Platinum has advantages over isotope labeling because it has a normalized unique isotopic distribution (194Pt (97.41%), 195Pt (100%); 196Pt (74.58%)), which allows for easy visual identification of cross-linked products in a spectrum without significantly complicating the spectrum or the need for intricate labeling procedures.48 As presented in Figure 3a, a Pt-bound peptide complex has a broader and more abundant isotopic distribution compared to unlabeled peptides in the same m/z region (CaM(38–74)).

Homobifunctional or heterobifunctional reactive groups

Homobifunctional cross-linking reagents contain the same functionality at both ends; heterobifunctional cross-linkers have two different reactive groups that target different functional groups. Cisplatin has four coordinated ligands; the chloride ligands are likely to be the first leaving groups to be replaced in reaction with proteins; depending on the type and number of coordination sites available and steric accessibility, the ammine ligand(s) can also be replaced. In particular, as shown above, sulfur ligands have high trans effects and can labilize trans NH3 ligands, especially at a low pH value. As cisplatin can bind to Met (S), His (N), Cys (S), or carboxyl (O) groups, it gives cisplatin the flexibility to be a homobifunctional, or heterobifunctional (or even heterotetrafunctional) cross-linking reagent. However, as with other homobifunctional reagents, there is the potential for creating a wide range of non-cross linked products.

Spacer arm length

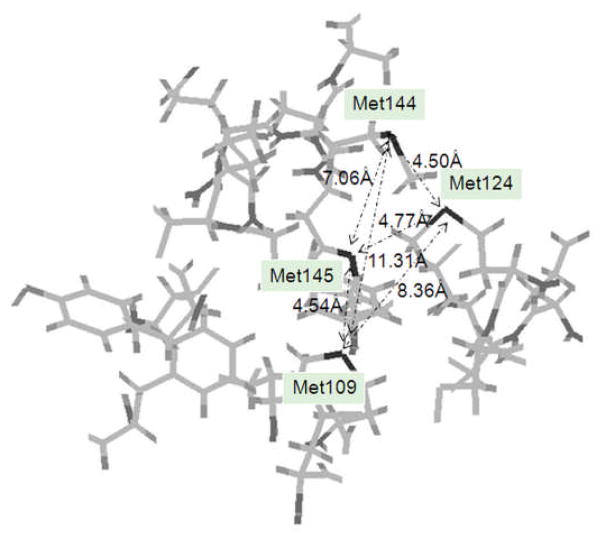

Cross-linkers are selected not only based on their chemical specificities and reactivities but also their arm-lengths. The spacer arm length of the cross-linker can provide an estimate of the distance between two linked groups. In the example of cisplatin cross-linking calmodulin, the spatial distances between the thioether sulfurs of Met109, Met124, Met144 and Met145 were based on the NMR structure of apo-calmodulin, (Figure 4, the S atom of Met145 was chosen as the center, only amino acid residues within 8 Å are shown),49 and range from 4.50 Å to 11.31 Å. Based on the literature for small platinum compounds,50 the average Pt-S bond length is 2.318 Å; thus the maximum spacer arm length of S-Pt-S is around 4.63 Å, which fits the spatial distance between Met109 and Met145 (4.54 Å). Therefore, it is likely platinum can readily trans-cross-link Met109 and Met145. Thus, that cisplatin fails to cross-link hemoglobin subunits is a bit surprising, because according to the crystal structure of hemoglobin complex(PDB-2DN2), the distance between His122 (α) -Cys112 (β) (4.10 Å) is within platinum cross-link range.51 Possible reasons may have to do with the steric accessibility or the chemistry of cisplatin cross-linking reactions. For example, the trans-labilization effect may play an important role in Pt cross-linking. Studies by Kasherman et al showed that thiols (Cys) and thioethers (Met) bind to Pt(II) at similar rates, but thioethers are significantly more efficient than thiols at labilizing the amine at lower pH,52 which might contribute to the unsuccessful Pt cross-linking of hemoglobin. Therefore, further research is still needed to explore the chemistry of cisplatin binding with proteins.

Figure 4.

Spatial distances between the thioether sulfurs of Met109, Met124, Met144 and Met145 of apo-calmodulin (PDB-1DMO).49 The S atom of Met145 is chosen as the center, only amino acid residues within 8 Å are shown. The thioether sulfurs of methionine residues are labeled in black. The distances indicate by double arrows between the thioether sulfurs of Met109, Met124, Met144 and Met145 range from 4.5 Å to 11.3 Å.

Cleavability

Cleavability is important in studies involving the bio-specific interactions between two molecules, which allow the verification of the cross-linking reactions through identification of the cross-linked sites. Cross-linkers can be cleaved either by chemical reactions or MS/MS fragmentation. The CAD and ECD spectra of all the Pt cross-linking products studied here have shown the cleavability of Pt-S or Pt-N bonds, which provides information on the modification sites. The effective CAD cleavability of platinum improves the information content in protein structure analysis and localization of the cross-linking sites.

CONCLUSIONS

This work effectively demonstrates the potential of cisplatin as a cross-linking reagent. The cross-linking sites were unambiguously assigned by use of high resolution FTICR MS data with sub-ppm mass accuracy; subsequent CAD and ECD FTICR MS data allowed the localization of the cross-linked sites on proteins. Cisplatin is a widely used clinical anticancer drug; it is water soluble (8 mM) and is able to penetrate membranes. Features of cisplatin, such as cross-linking DNA-DNA, DNA-protein, targeting new protein functional groups (thioether and imidazole groups), its unique isotopic pattern, and inherent two positive charges of platinum(II) make it a promising tool for cross-linking experiments in protein studies of more complicated biological systems by high resolution mass spectrometry in the future. However, the trans-labilizaiton effect of cisplatin and the binding of cisplatin to Cys (S) or carboxyl (O) group can complicate cross-linking results. Therefore, further efforts will have to be made in synthesizing novel cross-linkers, such as multinuclear platinum complexes, in order to understand better the chemistry of Pt cross-linking reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Warwick Postgraduate Research Scholarship (WPRS) and the Departmental Studentship for H. Li, the WPRS for Y. Zhao, and the EPSRC/WPRS funding for H. I. A. Phillips. Financial support from NIH (NIH/NIGMS-R01GM078293), the ERC (247450), the Warwick Centre for Analytical Science (EPSRC funded EP/F034210/1), and EPSRC (BP/G006792) are gratefully acknowledged. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Mark Barrow for his help with the instrument.

References

- 1.Back JP, de Jong L, Muijsers AO, de Koster CG. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:303–313. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00721-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinz A. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25:663–682. doi: 10.1002/mas.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinz A. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;381:44–47. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-2824-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller MQ, Dreiocker F, Ihling CH, Schäfer M, Sinz A. Anal Chem. 2010;82:6958–6968. doi: 10.1021/ac101241t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novak P, Haskins WE, Ayson MJ, Jacobsen RB, Schoeniger JS, Leavell MD, Young MM, Kruppa GH. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5101–5106. doi: 10.1021/ac040194r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y, Tang X, Weisbrod CR, Munske GR, Eng JK, von Haller PD, Kaiser NK, Bruce JE. Anal Chem. 2010;82:3556–3566. doi: 10.1021/ac902615g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang X, Bruce JE. Mol BioSyst. 2010;6:939–947. doi: 10.1039/b920876c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alloza I, Martens E, Hawthorne S, Vandenbroeck K. Anal Biochem. 2004;324:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tagwerker C, Flick K, Cui M, Guerrero C, Dou Y, Auer B, Baldi P, Huang L, Kaiser P. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:737–748. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500368-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu F, Mahrus S, Craik CS, Burlingame AL. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10362–10363. doi: 10.1021/ja0614159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrotchenko EV, Olkhovik VK, Borchers CH. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1167–1179. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T400016-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ihling C, Schmidt A, Kalkhof S, Schulz DM, Stingl C, Mechtler K, Haack M, Beck-Sickinger AG, Cooper DM, Sinz A. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1100–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taverner T, Hall NE, O’Hair RA, Simpson RJ. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46487–46492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermanson GT. Functional Targets. 2. Vol. 1. Academic Press; New York: Bioconjugate Techniques; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burstyn JN, Heiger-Bernays WJ, Cohen SM, Lippard SJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4237–4243. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malinge JM, Giraud-Panis MJ, Leng M. J Inorg Biochem. 1999;77:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wozniak K, Basiak J. Acta Biochim Pol. 2002;49:583–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boulikas T, Pantos A, Bellis E, Christofis P. Cancer Ther. 2007;5:537–583. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qu Y, Scarsdale NJ, Tran MC, Farrell NP. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zehnulova J, Kasparkova J, Farrell N, Brabec V. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22191–22199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103118200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegmans A, Berners-Price SJ, Davies MS, Thomas DS, Humphreys AS, Farrell N. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2166–2180. doi: 10.1021/ja036105u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Houten B, Illenye S, Qu Y, Farrell N. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11794–11801. doi: 10.1021/bi00095a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chvalova K, Brabec V, Kasparkova J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1812–1821. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kloster M, Kostrhunova H, Zaludova R, Malina J, Kasparkova J, Brabec V, Farrell N. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7776–7786. doi: 10.1021/bi030243e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeConti RC, Toftness BR, Lange RC, Creasey W. Cancer Res. 1973;33:1310–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo Y, Smith K, Petris MJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46393–46399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu W, Luo Q, Wu K, Li X, Wang F, Chen X, Ha X, Wang J, Liu J, ’Xiong S, Sadler PJ. Chem Comm. 2011 doi: 10.1039/C1CC11627d. In press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reedijk J. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2499–2510. doi: 10.1021/cr980422f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berners-Price SJ, Appleton TG. In: Platinum based drugs in cancer therapy. Kelland LR, Farrell NP, editors. Vol. 1. Huamna Press; Totowa, NJ: 2000. pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caravatti P, Allemann A. Org Mass Spectrom. 1991;26:514–518. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibson D, Costello CE. Eur Mass Spectrom. 1999;5:501–510. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Will J, Sheldrick WS. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:421–434. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knipp M, Karotki AV, Chesnov S, Natile G, Sadler PJ, Brabec V, Vašák M. J Med Chem. 2007;50:4075–4086. doi: 10.1021/jm070271l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Z, Liu Q, Liang X, Yang X, Wang N, Wang X, Sun H, Lu Y, Guo Z. Inorg Chem. 2009;14:1313–1323. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crider SE, Holbrook RJ, Franz KJ. Metallomics. 2010;1:74–83. doi: 10.1039/b916899k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qi YL, Thompson CJ, VanOrden S, O’Connor PB. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;22:138–147. doi: 10.1007/s13361-010-0006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Hair RAJ, Reid GE. Eur Mass Spectrom. 1999;5:325–334. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartinger CG, Tsybin YO, Fuchser J, Dyson PJ. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:17–19. doi: 10.1021/ic702236m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hohage O, Sheldrick WS. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:1506–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Neil KT, DeGrado WF. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:59–64. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90177-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelleher RL, Zubarev RA, Bush K, Furie B, Furie BC, McLafferty FW, Walsh CT. Anal Chem. 1999;71:4250–4253. doi: 10.1021/ac990684x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hahn M, Kleine M, Sheldrick WS. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6:556–566. doi: 10.1007/s007750100232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manka S, Becker F, Hohage O, Sheldrick WS. J Inorg Biochem. 2004;98:1947–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lau JKC, Deubel DV. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:2849–2855. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jamieson ER, Lippard SJ. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2467–2498. doi: 10.1021/cr980421n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandal R, Kalke R, Li XF. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:2748–2754. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li X, Cournoyer JL, Lin C, O’Connor PB. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:855–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams JP, Phillips Hazel IA, Campuzano I, Sadler PJ. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang MJ, Tanaka T, Ikura M. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:758–767. doi: 10.1038/nsb0995-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ienco A, Caporali M, Zanobini F, Mealli C. Inorg Chem. 2009:3840–3847. doi: 10.1021/ic8023748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park SY, Yokoyama T, Shibayama N, Shiro Y, Tame JR. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:690–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kasherman Y, Sturup S, Gibson D. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14:387–399. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.