Abstract

Methylocella spp. are facultative methanotrophs that grow on methane and multicarbon substrates, such as acetate. Acetate represses transcription of methane monooxygenase of Methylocella silvestris in laboratory culture. DNA stable-isotope probing (DNA-SIP) using 13C-methane and 12C-acetate, carried out with Methylocella-spiked peat soil, showed that acetate also repressed methane oxidation by Methylocella in environmental samples.

TEXT

Methanotrophs use methane (CH4) as their sole source of carbon and energy and are a major sink in the environment for this potent greenhouse gas (18, 20). Facultative methanotrophs, such as Methylocella silvestris, can also grow on substrates such as acetate, ethanol, pyruvate, succinate, and malate (4, 6, 7, 10, 19). Methanotrophs oxidize CH4 by using particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) or soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO) (15, 18, 20, 21). Methylocella spp., however, lack pMMO and oxidize CH4 using sMMO (19). Methylocella species are commonly found in acidic soils (2, 3, 5, 10). 13CH4 DNA stable-isotope probing (DNA-SIP) and phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analyses showed that Methylocella spp. oxidized CH4 in peat soil (2, 3). However, the contribution of Methylocella to CH4 oxidation in natural peatlands is uncertain (7, 19). Methylocella spp. might use alternative carbon sources present, such as acetate (8), a major intermediate in the degradation of organic matter in soil (8, 12, 13). We previously showed that acetate represses transcription of sMMO of M. silvestris in culture (19) and speculated that acetate may repress CH4 oxidation by Methylocella species in soil (2). Here, we applied 13C-DNA-SIP (16) to test the hypothesis that acetate represses CH4 oxidation by M. silvestris in peat soil microcosms.

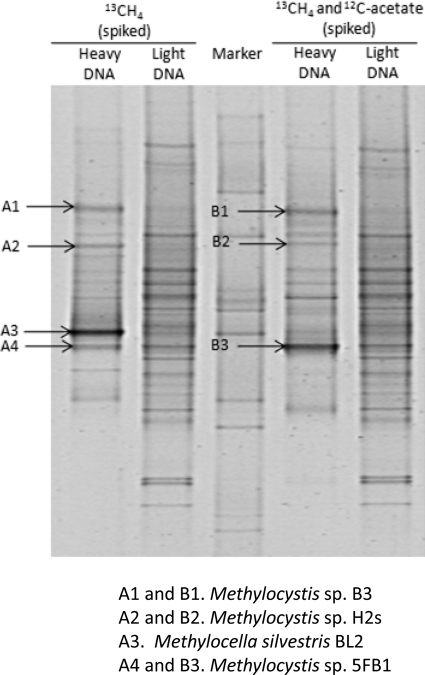

In this experiment, we used peat soil from Moor House Nature Reserve (England). Methylocella spp. have previously been reported to be active in CH4 oxidation in Moor House peat soil (2, 3). Soil samples (top 10 cm with vegetation removed) were taken from a Calluna-covered intact peat core in June 2008 to set up the microcosm incubations (see the supplemental material). DNA-SIP experiments using 13CH4 and appropriate 12CH4 controls demonstrated that Methylocystis spp., and not Methylocella spp., were the major methane utilizers in these samples (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), even though Methylocella spp. were present in the samples we used in this study (17, data not shown). Since we were interested to see if Methylocella spp. are actively involved in the utilization of CH4 in the presence of acetate as an alternative carbon source, we spiked the Moor House peat soil with M. silvestris. We chose to spike the soil with 1 × 106 cells g−1 of soil, based on earlier work by Dedysh et al. (5), who, using fluorescence in situ hybridization, estimated the quantity of Methylocella spp. in Sphagnum peat to be around 1 × 106 cells per g of soil. Addition of M. silvestris increased the ability of the peat soil microcosms to oxidize CH4 compared to that of the original non-Methylocella spiked soil, indicating that added M. silvestris contributed to enhanced CH4 oxidation (Fig. 1). DNA-SIP experiments were then carried out with 13CH4 using M. silvestris-spiked soil. As expected, bacterial 16S rRNA gene-specific denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) carried out with the 13CH4 “heavy” DNA identified M. silvestris as the dominant active methanotroph (Fig. 2), indicating that added M. silvestris was actively utilizing CH4 in the microcosms.

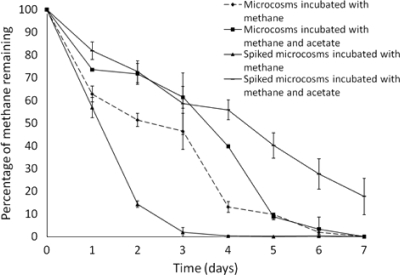

Fig. 1.

Ability of the Moor House peat soil to oxidize methane (2% [vol/vol] in headspace) in microcosms derived from original nonspiked and Methylocella silvestris-spiked Moor House peat soil, in the presence or absence of 0.5 mM sodium acetate. The percentage of methane remaining indicates the remaining methane from the original 2% (vol/vol) headspace methane injected into each microcosm. Error bars indicate the standard deviations from triplicate methane concentration measurements.

Fig. 2.

DGGE fingerprint profiles of 16S rRNA gene PCR products of “heavy” and “light” DNA retrieved from the Methylocella silvestris-spiked Moor House peat soil incubated with 13CH4 in the presence or absence of 12C-acetate. Enriched DGGE bands that were excised for reamplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA genes are indicated with arrows.

We then investigated whether acetate would repress methane oxidation by Methylocella in these soil microcosms. The effect of 0.5 mM acetate on the ability of the M. silvestris-spiked soil and original nonspiked soil to oxidize CH4 was tested (Fig. 1). The concentration of acetate present in the Moor House peat soil after storage for 1 week was below the detection limit (0.1 mM) of the assay applied here. The concentrations of available acetate in soil are variable. In Beech forest soil, acetate concentrations can reach up to ∼3.5 mM (15), while in rice field soil, the concentration of accumulated acetate can reach up to 7 mM (14). In the pore water of peat, the concentrations of acetate vary from a few μM to 1 mM (9). Therefore, we chose a concentration of 0.5 mM acetate, which is in the medium range of in situ concentrations of acetate observed in peat soil, in order to observe the effect of acetate on CH4 oxidation. Acetate had no major impact on the ability of the original nonspiked soil to oxidize CH4 (Fig. 1), indicating that acetate is unlikely to affect methane oxidation by Methylocystis spp. present in this soil, although very recent studies indicate that some Methylocystis species also use acetate (1, 11). However, acetate reduced the ability of the M. silvestris-spiked soil microcosms to oxidize CH4 compared to that of the control (M. silvestris-spiked soil without addition of acetate), suggesting that acetate repressed the ability of M. silvestris to oxidize CH4 in peat soil microcosms. This confirms previous reports showing that acetate represses the transcription of sMMO in M. silvestris in vitro (7, 19).

To address whether M. silvestris assimilated carbon from methane in the presence of acetate in these soil microcosms, DNA-SIP experiments were carried out with M. silvestris-spiked soil supplied with 13CH4 in the presence of 0.5 mM 12C-sodium acetate. The bacterial 16S rRNA gene-specific DGGE profiles retrieved from the 13CH4 “heavy” DNA and from the 13CH4 plus 12C-acetate “heavy” DNA are presented in Fig. 2. Based on the sequence information of the enriched bacterial 16S rRNA gene-specific DGGE band retrieved from the 13CH4 “heavy” DNA, we observed that M. silvestris was the dominant active methanotroph in the spiked soil without acetate, while its signature 16S rRNA gene band disappeared in the DGGE profile originating from the 13CH4 and 12C-acetate “heavy” DNA (Fig. 2). We also constructed an mmoX clone library with the “heavy” DNA retrieved from 13CH4 plus 12C-acetate microcosms. A total of 36 mmoX clones were analyzed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), and two operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were obtained. We did not detect any mmoX sequences related to Methylocella spp. (data not shown). Therefore, both 16S rRNA gene-specific DGGE analyses and mmoX gene clone library data obtained with the 13CH4 plus 12C-acetate “heavy” DNA demonstrated that in the presence of acetate, M. silvestris did not utilize CH4 in peat soil microcosms, which confirms previous observations in pure culture (19).

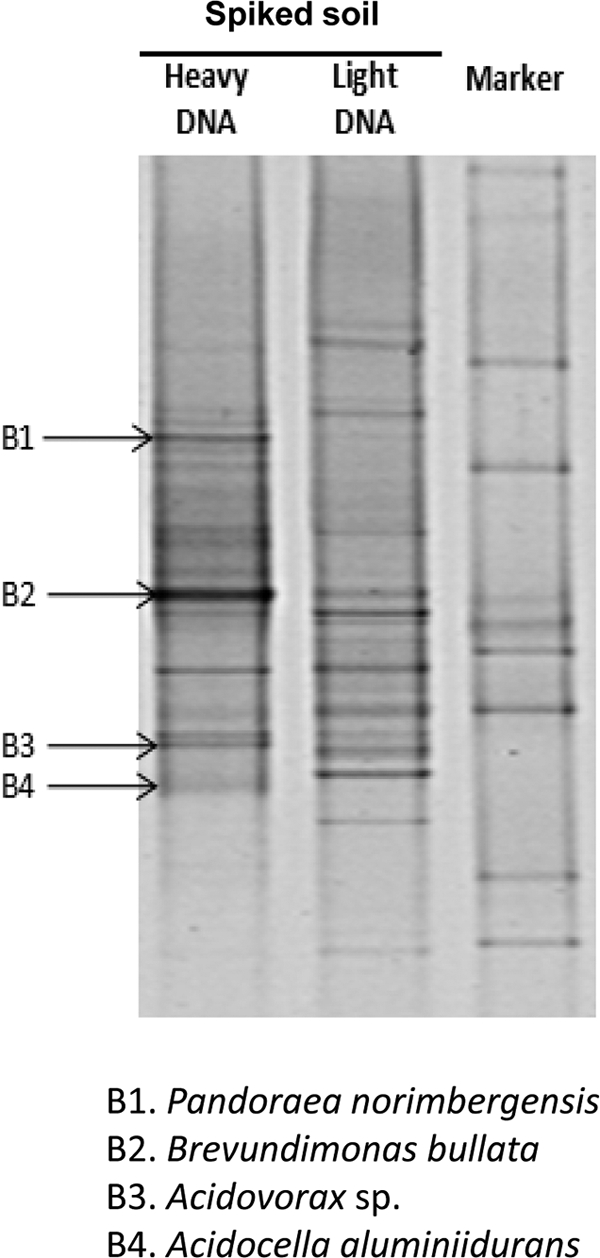

Further DNA-SIP experiments were carried out to investigate whether M. silvestris was the dominant acetate utilizer in microcosms. 13C-acetate DNA-SIP experiments were carried out with M. silvestris-spiked Moor House peat soil. In these experiments, 5.0 mM acetate was used, since SIP experiments with 0.5 mM acetate failed to achieve sufficient labeling of DNA for a successful DNA-SIP incubation. Bacterial 16S rRNA gene-specific DGGE carried out with the “heavy” DNA retrieved from the M. silvestris-spiked 13C-acetate soils showed several enriched bands compared to the “light” DNA (Fig. 3); however, no Methylocella-like sequences were detected as enriched bands during DGGE fingerprint analyses. This was also confirmed by further clone library analyses of 16S rRNA genes using the 13C-acetate “heavy” DNA retrieved from M. silvestris-spiked soil (data not shown). These data suggest that Methylocella spp. were not significant acetate utilizers in the peat soil microcosms under the conditions used in these experiments. It is likely that Methylocella spp. were outcompeted by more efficient acetate utilizers in this peat soil. This observation is further supported by the acetate uptake data obtained from the nonspiked and M. silvestris-spiked soil. We observed virtually no difference in the abilities of the M. silvestris-spiked soil and the nonspiked soil to remove acetate in microcosms (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Fig. 3.

DGGE fingerprint profiles of 16S rRNA gene PCR products derived from “heavy” and “light” DNA retrieved from Methylocella silvestris-spiked Moor House peat soil incubated with 13C-acetate. Enriched DGGE bands that were excised for reamplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA genes are indicated with arrows.

In conclusion, spiking of the Moor House peat soil with M. silvestris increased its ability to oxidize CH4 in microcosms, and acetate at 0.5 mM reduced the ability of the M. silvestris-spiked peat soil to oxidize CH4. DNA-SIP experiments using 13C-methane and 12C-acetate suggest that this was due to acetate inhibiting CH4 oxidation by M. silvestris, although Methylocella spp. were not the dominant acetate utilizers in these peat soil microcosms.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Niall McNamara at CEH, Lancaster, for providing the Moor House peat soil and Anita Catherwood at the University of Warwick for help with high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses.

This work was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council, United Kingdom, through grant NE/E016855/1. M.T.R. was supported through a University of Warwick Overseas Research Studentship.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 22 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Belova S. E., et al. 2011. Acetate utilization as a survival strategy of peat-inhabiting Methylocystis spp. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3:36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen Y., et al. 2008. Diversity of the active methanotrophic community in acidic peatlands as assessed by mRNA and SIP-PLFA analyses. Environ. Microbiol. 10:446–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen Y., et al. 2008. Revealing the uncultivated majority: combining DNA stable-isotope probing, multiple displacement amplification and metagenomic analyses of uncultivated Methylocystis in acidic peatlands. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2609–2622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dedysh S. N., et al. 2000. Methylocella palustris gen. nov., sp. nov., a new methane-oxidizing acidophilic bacterium from peat bogs, representing a novel subtype of serine-pathway methanotrophs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:955–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dedysh S. N., Derakshani M., Liesack W. 2001. Detection and enumeration of methanotrophs in acidic Sphagnum peat by 16S rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization, including the use of newly developed oligonucleotide probes for Methylocella palustris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4850–4857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dedysh S. N., et al. 2004. Methylocella tundrae sp. nov., a novel methanotrophic bacterium from acidic tundra peatlands. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dedysh S. N., Knief C., Dunfield P. F. 2005. Methylocella species are facultatively methanotrophic. J. Bacteriol. 187:4665–4670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drake H. L., Küsel K., Matthies C. C. 2006. Acetogenic prokaryotes, p. 354–420 In Balows A., Trüper H. G., Dworkin M., Harder W., Schleifer K. H. (ed.), The prokaryotes. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duddleston K. N., Kinney M. A. 2002. Anaerobic microbial biogeochemistry in a northern bog: acetate as a dominant metabolic end product. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 16:1–9 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dunfield P. F., Khmelenina V. N., Suzina N. E., Trotsenko Y. A., Dedysh S. N. 2003. Methylocella silvestris sp. nov., a novel methanotroph isolated from an acidic forest cambisol. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1231–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Im J., Semrau J. D. 2011. Pollutant degradation by a Methylocystis strain SB2 grown on ethanol: bioremediation via facultative methanotrophy. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Küsel K., Drake H. L. 1995. Effects of environmental parameters on the formation and turnover of acetate by forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3667–3675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Küsel K., Drake H. L. 1999. Microbial turnover of low molecular organic acids during leaf litter decomposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 31:107–118 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu F., Conrad R. 2010. Thermoanaerobacteriaceae oxidize acetate in methanogenic rice field soil at 50°C. Environ. Microbiol. 12:2341–2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McDonald I. R., Uchiyama H., Kambe S., Yagi O., Murrell J. C. 1997. The soluble methane monooxygenase gene cluster of the trichloroethylene-degrading methanotroph Methylocystis sp. strain M. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1898–1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Radajewski S., Ineson P., Parekh N. R., Murrell M. J. 2000. Stable-isotope probing as a tool in microbial ecology. Nature 403:646–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rahman M. T., et al. 2010. Environmental distribution and abundance of the facultative methanotroph Methylocella. ISME J. [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1038/ismej.2010.190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Semrau J. D., DiSpirito A. A., Yoon S. 2010. Methanotrophs and copper. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:496–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Theisen A. R., et al. 2005. Regulation of methane oxidation in the facultative methanotroph Methylocella silvestris BL2. Mol. Microbiol. 58:682–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Trotsenko Y. A., Murrell J. C. 2008. Metabolic aspects of aerobic obligate methanotrophy. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 63:183–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vorobev A. V., et al. 2010. Methyloferula stellata gen. nov., sp. nov., an acidophilic, obligately methanotrophic bacterium possessing only a soluble methane monooxygenase. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.028118-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.