Abstract

Human sapovirus sequences were identified in 12 (100%) influent and 7 (58%) effluent wastewater samples collected once a month for a year. The strains were characterized based on their partial capsid gene sequences and classified into 10 genotypes, demonstrating that genetically diverse sapovirus strains infect humans in the study area.

TEXT

The Caliciviridae family members sapoviruses (SaVs) and noroviruses (NoVs) are nonenveloped viruses possessing a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome, and these viruses cause the majority of human cases of acute gastroenteritis worldwide (2). They have been detected in fecal samples from infected patients as well as in environmental samples, such as wastewater, river water, and bivalves (3–5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 16, 18), suggesting their transmission via fecal-oral routes through person-to-person contact and through contaminated foods and water. Caliciviruses, namely, SaVs and NoVs, are included in the latest U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's contaminant candidate list (CCL3), which identifies emerging contaminants in aquatic environments that may pose risks to public health (19). Compared with that for NoVs, information regarding the occurrence and fate of SaVs during water treatment and in the environment is quite limited.

Recently, we developed a nested reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assay utilizing a broadly reactive primer and successfully identified human SaV strains in river water receiving effluents from several wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) (11). The present study aimed to confirm the usefulness of the assay for other types of water samples, namely, wastewater samples, and to investigate the prevalence and genotype distribution of human SaVs in wastewater in Japan. The presence of human SaV genomes in the wastewater samples was determined by a quantitative real-time RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) and two separate nested RT-PCR assays, including the recently developed assay, and the strains were further characterized based on their partial capsid gene sequences.

Between March 2005 and February 2006, 24 wastewater samples (12 influent and 12 effluent) were collected monthly from a WWTP located in an urbanized area in Japan; the plant utilized a conventional activated sludge process. These samples (100 ml influent and 1,000 ml effluent) were concentrated by the adsorption-elution method using an electronegative filter (catalog no. HAWP-090-00; Millipore, Tokyo, Japan) and a Centriprep YM-50 device to obtain a final volume of 700 μl, as previously described (9). Viral RNA was then extracted using a QIAamp viral RNA minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), followed by RT using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

The presence of SaV genomes was first examined with a TaqMan-based RT-qPCR using an ABI Prism 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The primers (SaV124F/1F/5F and SaV1245R) and TaqMan MGB probes (SaV124TP/5TP) were designed to amplify all human SaV genogroups (genogroup I [GI], GII, GIV, and GV) (13). A 10-fold serial dilution of the standard plasmid DNA was used to make a standard curve, enabling us to obtain quantitative data on SaV genomes in the wastewater samples. The qPCRs were performed in duplicate (i.e., two PCR tubes per sample) and considered positive only when both tubes fluoresced with sufficient intensity and the average cycle threshold (CT) value was not more than 40, as recommended by the guidelines described elsewhere (1).

A recently developed nested PCR assay (11) (nested PCR no. 1) and a widely used assay (15) (nested PCR no. 2) were performed to generate approximately 430- and 440-bp products, respectively, of the partial capsid gene using Ex Taq Hot Start DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Bio Co., Shiga, Japan). Nested PCR no. 1 was performed using SaV124F/1F/5F and SV-R13/R14 primers and 1245Rfwd and SV-R2 primers for first- and second-round PCR, respectively. This assay showed the highest efficiency in detecting SaVs in river water samples among several nested PCR assays tested (11). Nested PCR no. 2 was performed using SV-F13/F14 and SV-R13/R14 primers and SV-F22 and SV-R2 primers for first- and second-round PCR, respectively (15). This assay is widely used to detect SaVs in clinical and environmental samples (4–6, 8, 18). Negative controls were included to avoid false-positive results due to cross-contamination, and no false-positive nested PCR product was observed. Second-round PCR products of expected size were cloned into the pCR4-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Eight clones per sample were selected, and both strands were sequenced using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit and a 3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Nucleotide sequences were aligned using ClustalW version 1.83 (http://clustalw.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/top-e.html), and distances were calculated by Kimura's two-parameter method (10).

Table 1 summarizes the results of detection of human SaV genomes in 12 influent and 12 effluent wastewater samples. By use of an RT-qPCR assay, SaV genomes were detected in all influent and 5 (42%) effluent samples. The influent sample collected in February 2006 exhibited a minimum cycle threshold (CT) value of 32.7, which represents the highest SaV genome concentration of 9.3 × 104 copies/liter (Table 1). This result is consistent with the increase in the number of gastroenteritis patients with SaV infection during winter in Japan (6, 14). Human SaV genomes were identified in all influent samples collected monthly for 1 year, even in summer (nonepidemic period), suggesting that human SaV infections occurred throughout the year in at least the study area. By using nested PCR no. 1 or 2, human SaV sequences were obtained from all real-time PCR-positive samples (Table 1). Nested PCR no. 1 (18/24) showed a higher overall detection rate than nested PCR no. 2 (15/24), which is consistent with our previous observations on river water samples (11). These results demonstrate that the recently developed nested PCR assay (nested PCR no. 1) sensitively detects human SaV genomes in both river water and wastewater samples and therefore should also be applicable for analyzing a wide range of environmental water samples.

Table 1.

Detection of sapoviruses in wastewater in Japan

| Yr and mo of sample collection | Influent samples |

Effluent samples |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR resulta |

Nested PCR resultb |

Genotype(s) | qPCR result |

Nested PCR result |

Genotype(s) | |||||

| CT | Copies/liter | No. 1 | No. 2 | CT | Copies/liter | No. 1 | No. 2 | |||

| 2005 | ||||||||||

| Mar | 35.5 | 1.6 × 104 | + | + | GI/1, GI/2, GII/1, GII/2 | 38.2 | 2.9 × 103 | + | + | GI/1, GII/1 |

| Apr | 34.2 | 3.6 × 104 | + | + | GI/2, GI/3, GII/1 | 38.4 | 2.6 × 103 | + | + | GI/2, GI/3 |

| May | 34.3 | 3.3 × 104 | + | + | GI/1, GI/2, GI/3, GII/1 | 37.2 | 5.7 × 103 | + | + | GI/3, GII/1 |

| June | 35.6 | 1.5 × 104 | + | + | GI/1, GI/2, GI/3, GI/5, GI/untyped, GII/1 | − | + | + | GI/3, GI/untyped | |

| July | 35.1 | 2.1 × 104 | + | + | GI/1 | − | − | − | ||

| Aug | 37.4 | 4.9 × 103 | − | + | GI/2, GII/5 | − | − | − | ||

| Sept | 38.4 | 2.8 × 103 | + | − | GI/2 | − | − | − | ||

| Oct | 37.5 | 4.6 × 103 | + | − | GI/3 | − | − | − | ||

| Nov | 35.9 | 1.2 × 104 | + | + | GI/1, GI/4, GII/1, GV/1 | − | + | − | GI/4 | |

| Dec | 33.5 | 5.6 × 104 | + | + | GI/1, GI/2, GII/1 | − | − | − | ||

| 2006 | ||||||||||

| Jan | 33.7 | 4.9 × 104 | + | + | GI/1, GI/2, GI/5, GII/1 | 37.7 | 4.1 × 103 | + | − | GI/4 |

| Feb | 32.7 | 9.3 × 104 | + | + | GI/1, GI/2, GI/untyped, GII/1 | 36.7 | 8.1 × 103 | + | + | GI/2, GI/3 |

CT results indicate average values from two PCR tubes. qPCR results were 100% positive for influent samples and 42% positive for effluent samples.

No. 1, nested PCR assay described by Kitajima et al. (11); no. 2, nested PCR assay described by Okada et al. (15). +, positive; −, negative. Nested PCR no. 1 results were 92% positive for influent samples and 58% positive for effluent samples; nested PCR no. 2 results were 83% positive for influent samples and 42% positive for effluent samples.

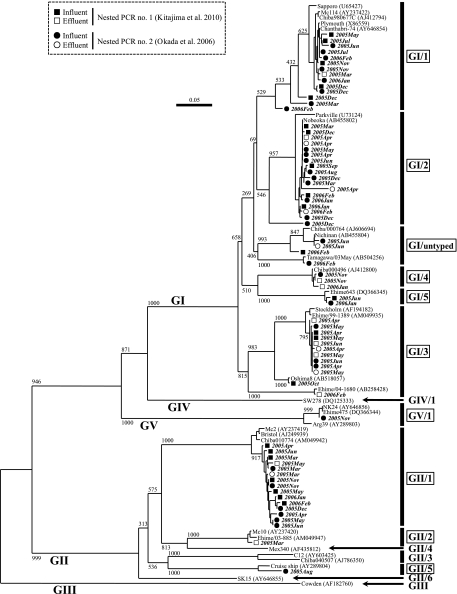

Based on the sequence analysis, SaV strains detected were classified into 10 genotypes: GI/1, GI/2, GI/3, GI/4, GI/5, GI/untyped, GII/1, GII/2, GII/5, and GV/1 (Fig. 1). Multiple genotypes coexisted in 9 influent and 5 effluent samples (Table 1), suggesting the prevalence of human SaV infections due to genetically diverse strains in the study area. Human SaVs are becoming more prevalent worldwide and are recognized as an emerging pathogen associated with human gastroenteritis (6, 17). The present study describes novel findings on the prevalence, seasonality, and genotype distribution of SaVs in wastewater, suggesting that genetically diverse SaVs are circulating among humans and aquatic environments of Japan, with a high prevalence in winter.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of SaV strains based on about 400 nucleotides (nt) of the partial capsid gene sequences. The tree was generated using the neighbor-joining method, with representative strains derived from wastewater and reference strains. The numbers on each branch indicate the bootstrap values, where values of 950 or higher were considered statistically significant for grouping. The scale indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. GI/1, GI/2, GI/3, GI/4, GI/5, GI/untyped, GII/1, GII/2, GII/5, and GV/1 (boxed) are genotypes identified in the present study.

We intend to search for SaVs in environmental samples, such as surface water, seawater, and shellfish, by combining RT-qPCR (13) and nested RT-PCR assays (11), which can serve as a powerful tool for identifying and characterizing human SaVs. Since only a few reports on the occurrence of human SaVs in the environment outside Japan are available (12, 16), further environmental studies, even in combination with clinical studies, are required worldwide to understand SaV epidemiology, temporal and geographical distribution, and potential health risks to humans.

Nucleotide accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AB602078 to AB602248.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate Tomoichiro Oka and Kazuhiko Katayama at the National Institute of Infectious Disease, Japan, for kindly providing standard plasmid DNA of human SaVs. We also appreciate Hozue Kuroda at The University of Tokyo for her technical assistance.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A) under project number 20686035 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bustin S. A., et al. 2009. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 55: 611–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Green K. Y. 2007. Caliciviridae: the noroviruses, p. 949–979 In Knipe D., et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greening G. E., Wolf S. 2010. Calicivirus environmental contamination, p. 25–44 In Hansman G. S., Jiang X., Green K. Y. (ed.), Caliciviruses: molecular and cellular virology. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hansman G. S., et al. 2007. Human sapovirus in clams, Japan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13: 620–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hansman G. S., et al. 2007. Sapovirus in water, Japan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13: 133–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harada S., et al. 2009. Surveillance of pathogens in outpatients with gastroenteritis and characterization of sapovirus strains between 2002 and 2007 in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. J. Med. Virol. 81: 1117–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haramoto E., Katayama H., Phanuwan C., Ohgaki S. 2008. Quantitative detection of sapoviruses in wastewater and river water in Japan. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 46: 408–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iizuka S., et al. 2010. Detection of sapoviruses and noroviruses in an outbreak of gastroenteritis linked genetically to shellfish. J. Med. Virol. 82: 1247–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katayama H., Shimasaki A., Ohgaki S. 2002. Development of a virus concentration method and its application to detection of enterovirus and Norwalk virus from coastal seawater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68: 1033–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kimura M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16: 111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitajima M., et al. 2010. Detection and genetic analysis of human sapoviruses in river water in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76: 2461–2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kiulia N. M., et al. 2010. The detection of enteric viruses in selected urban and rural river water and sewage in Kenya, with special reference to rotaviruses. J. Appl. Microbiol. 109: 818–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oka T., et al. 2006. Detection of human sapovirus by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J. Med. Virol. 78: 1347–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Okada M., Shinozaki K., Ogawa T., Kaiho I. 2002. Molecular epidemiology and phylogenetic analysis of Sapporo-like viruses. Arch. Virol. 147: 1445–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Okada M., Yamashita Y., Oseto M., Shinozaki K. 2006. The detection of human sapoviruses with universal and genogroup-specific primers. Arch. Virol. 151: 2503–2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sano D., et al. 2011. Quantification and genotyping of human sapoviruses in the Llobregat River catchment, Spain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77: 1111–1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Svraka S., et al. 2010. Epidemiology and genotype analysis of emerging sapovirus-associated infections across Europe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48: 2191–2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ueki Y., et al. 2010. Detection of sapovirus in oysters. Microbiol. Immunol. 54: 483–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2009. Drinking water contaminant candidate list 3—final. Fed. Regist. 74: 51850–51862 [Google Scholar]