Abstract

Three whole-community genome amplification methods, Bst, REPLI-g, and Templiphi, were evaluated using a microarray-based approach. The amplification biases of all methods were <3-fold. For pure-culture DNA, REPLI-g and Templiphi showed less bias than Bst. For community DNA, REPLI-g showed the least bias and highest number of genes, while Bst had the highest success rate and was suitable for low-quality DNA.

TEXT

Microarray-based hybridization, with its high-throughput advantage, has become an effective tool for the comprehensive analysis of environmental microbial communities. Several types of microarrays, including functional gene arrays (21, 23), community genome arrays (27), and phylogenetic oligonucleotide arrays (8), have been developed and applied to understand the structure, function, and dynamic of microbial communities. However, it is estimated that genomic DNA from approximately 107 cells is needed to obtain reasonably strong hybridization on 50-mer-based oligonucleotide microarrays for single-copy genes (21). Because a relatively large amount of DNA is needed for detecting less dominant microbial populations in environmental samples, their detection power can be limited by the amount of DNA available, especially in samples with low biomass and/or low DNA yield.

Multiple displacement amplification (MDA) was developed for whole-community genome amplification (WCGA) from small amounts of DNA to overcome limitations due to DNA amounts (5). WCGA is based on the annealing of random primers to denatured DNA followed by strand-displacement synthesis, and it results in high-molecular-weight (12- to 100-kb) DNA products (3). As DNA is synthesized by strand displacement, gradually increasing numbers of priming events occur, forming a network of hyperbranched DNA structures. Compared to PCR-based WCGA, MDA showed higher fidelity and less amplification bias (overestimation or underestimation of different genes) (16, 18, 28). This reaction can be catalyzed by either phi29 (phi29) or the large fragment of Bst (Bst) DNA polymerases.

phi29, the replicative polymerase from the Bacillus subtilis phage phi29, possesses a proofreading activity with an error rate of 1 per 106 to 107 (6) and was well evaluated for human DNA and microbial community analysis (14, 26). Bst, which does not have proofreading activity and has a higher error rate of 1.5 per 105 (13), was used to amplify human DNA (15) and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues and was found to have a <3-fold representational bias (1). The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare different MDA methods using either phi29 or Bst for microbial community amplification. Microarray-based analysis was performed to examine genome coverage and amplification bias.

Pure cultures, environmental samples, and DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted from Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough, Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009, and Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus X514 as previously described (30). To evaluate the performance of WCGA methods on community DNA, a soil sample from the USDA-ARS High Plains Grasslands Research Station (Cheyenne, WY) was used. DNA was extracted from 5 g of soil as previously described (29).

DNA amplification, labeling, and microarray hybridization.

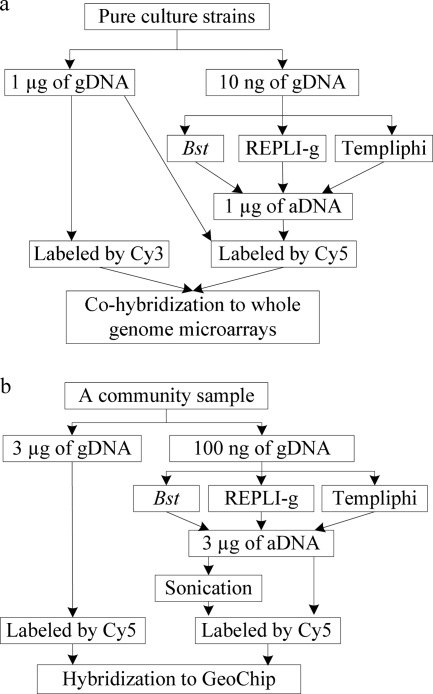

The outlines of all experiments are shown in Fig. 1. Three MDA methods, Bst (14) and two commercial phi29-based kits, REPLI-g (REPLI-g ultrafast minikit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and Templiphi (Illustra Templiphi amplification kit; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), were evaluated for whole-genome or whole-community genome amplification. An aliquot of pure-culture DNA (10 ng) or community DNA (100 ng) was amplified with both methods as described by Lage et al. (15) for Bst, by Wu et al. (26) for Templiphi, and by the manufacturer's manual for REPLI-g. DNA concentrations were determined by PicoGreen (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For pure cultures, the same amounts (1 μg) of unamplified genomic DNA (gDNA) and amplified DNA (aDNA) were fluorescently labeled with Cy3 and Cy5, respectively, as previously described (24). Labeled aDNA was mixed with the gDNA and cohybridized with whole-genome microarrays at 45°C for 10 h. For the community sample, aDNA was fragmented by sonication to an average size of ∼600 bp. gDNA or aDNA (3.0 μg) with or without sonication was labeled with Cy5 as described above, and labeled community DNA was hybridized to Geochip 3.0 (10), which contains over 24,000 probes for microbial functional genes involved in C, N, S, and P cycling, metal reduction, and organic remediation at 42°C for 10 h. All experiments were performed in triplicate using an HS4800Pro hybridization station (TECAN, San Jose, CA). Microarray scanning and data processing were performed as described previously (26) except that the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was set at 2.0 (12) for the selection and removal of bad spots. The cluster analysis was performed using the unweighted pair-wise average-linkage hierarchical clustering algorithm (7) with R project (www.r-project.org).

Fig. 1.

Outline of evaluation of three MDA methods using pure cultures (a) and a community sample (b). gDNA, unamplified genomic DNA; aDNA, amplified DNA.

DNA yield.

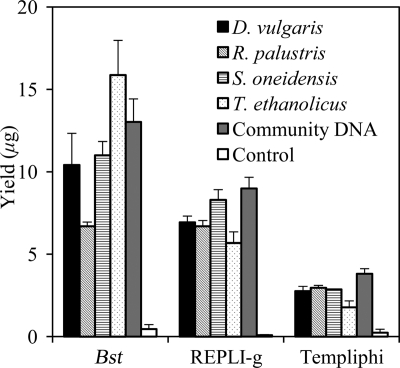

MDA is performed under isothermal conditions. The incubation temperatures for Bst, REPLI-g, and Templiphi were 50°C, 30°C, and 30°C, respectively. Amplification with Bst produced larger amounts of DNA than both phi29 kits. For pure cultures, Bst yielded 6.7 to 11.0 μg of DNA, while REPLI-g and Templiphi produced 5.7 to 8.3 μg and 1.6 to 2.9 μg, respectively. For communities, Bst produced 13.0 μg, while REPLI-g and Templiphi produced 9.0 μg and 3.8 μg of DNA, respectively (Fig. 2 ). The DNA yield was affected by the amount of DNA template, the incubation time, and the composition of the reaction buffer. The amounts of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) in Bst, REPLI-g, and Templiphi were about 24 μg, 20 μg, and 8 μg, respectively, a possible reason for the yield differences. Considering the incubation times (10 h for Bst, 1.5 h for REPLI-g, and 3 h for Templiphi), REPLI-g demonstrated the highest amplification efficiency, with fold increases of approximately 3.8 × 102 to 5.5 × 102 per hour in DNA for pure cultures and 60 per hour for community DNA.

Fig. 2.

Yields of the three amplification methods for pure culture and community DNA. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the results for 3 replicates.

Amplification representativeness for pure cultures.

The representativeness of pure-culture aDNA was determined using whole-genome open reading frame (ORF) microarrays. All three methods showed a high genome coverage (>99%) but a higher representational bias than was found for gDNA (Table 1; also see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The representational biases for gDNA and aDNA amplified by Bst, REPLI-g, and Templiphi were 0.02 to 0.04, 0.20 to 0.27, 0.08 to 0.11, and 0.09 to 0.20. Wu et al. (26) evaluated Templiphi for whole-genome amplification (WGA) using three pure cultures and showed lower but comparable biases. The proportion of genes whose hybridization signal ratios (aDNA/gDNA) showed 1.5-fold or greater differences was 0 for REPLI-g. For Templiphi, 0 to 1.4% of the genes showed a 1.5-fold difference, and none of the genes showed greater differences. However, Bst resulted in a higher percentage of genes showing differences, with 0.9 to 8.6%, 0 to 1.2%, and none of the genes showing >1.5-, 2.0-, and 3.0-fold differences, respectively (Table 1). The MDA methods showed different levels of bias with each pure culture. This could be due to uneven amplification in the regions of enzyme displacement, or errors in DNA quantitation may have resulted in different amounts of aDNA and gDNA being used for hybridization. REPLI-g showed the lowest coefficient of variation of representational biases, indicating that it performed similarly with different genomes. These results suggest that for amplification of pure cultures, all three MDA methods showed high genome coverage and a <3-fold bias. However, REPLI-g and Templiphi worked similarly and showed better results than Bst in terms of representational bias. Furthermore, no significant correlation was observed between GC contents and the hybridization signal ratios. We also found that the biased genes in aDNA produced by the different MDA methods were different and the biased genes within replicates were consistent (see Fig. S3 and S4 in the supplemental material). Thus, we inferred that the bias was a combination of random processes, such as the initial random priming and/or DNA breakage (28) and the preferences of the reaction systems of the MDA methods.

Table 1.

Results for whole-community genome DNA amplification obtained with the three MDA methods for the four pure culturesa

| Parameter |

D. vulgaris |

R. palustris |

S. oneidensis |

T. ethanolicus |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gb | B | R | T | g | B | R | T | g | B | R | T | g | B | R | T | |

| Total no. of genes detectedc | 3,575 | 3,557 | 3,563 | 3,575 | 5,334 | 5,336 | 5,340 | 5,333 | 5,069 | 5,088 | 5,037 | 5,101 | 2,268 | 2,267 | 2,269 | 2,267 |

| Average Cy5/Cy3 ratiod | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Representational biase | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| SDG0.01f | 11.4 | 18.6 | 25.5 | 15.9 | 2.7 | 45.3 | 28.6 | 26.3 | 3.35 | 57.4 | 17.3 | 10.6 | 4.83 | 26.3 | 25.2 | 29.4 |

| F1.5g | 0 | 8.58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.92 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.02 | 0 | 1.35 | 0 | 1.18 | 0 | 0 |

| F2.0 | 0 | 1.15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F3.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F4.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Genomic DNA (1 μg) were labeled with both Cy3 and Cy5 in triplicate and cohybridized with whole-genome ORF arrays. Genomic DNA (10 ng) from individual genomes were amplified with the three MDA methods in triplicate. The amplified DNA (1 μg) was labeled with Cy5, whereas the unamplified genomic DNA (1 μg) was labeled with Cy3. Both Cy3- and Cy5-labeled DNA were cohybridized with whole-genome ORF arrays.

g, gDNA; B, Bst; R, Repli-g; T, Templiphi.

Poor spots with SNRs [SNR = (signal − background)/SDbackground] of <2 were removed (SD, standard deviation). Gene detection was considered positive when a positive hybridization signal was obtained from >51% of spots targeting the gene in all replicates. This number is to calculate the genome coverage.

The average ratio of signal intensity of the Cy5 channel to the Cy3 channel for each gene.

Representational bias, Djtotal (=, where Rij is the ratio of signal intensity of amplified to unamplified DNA and Nj is the number of genes detected in the unamplified DNA).

Percentage of genes whose signal ratios of amplified to unamplified DNA are significantly different from 1 at a P value of 0.01.

F1.5, F2.0, F3.0, and F4.0 indicate the percentages of genes whose signal ratios are larger than 1.5-, 2.0-, 3.0-, and 4-fold, respectively.

Amplification representativeness for a community sample.

To evaluate amplification representativeness for environmental samples, in which the gene diversity is more complex than in pure or mixed cultures, DNA from a soil sample was used (Table 2; also see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In total, 781 genes were detected using gDNA. For REPLI-g aDNA, 91% of the genes detected using gDNA were positive, with an additional 733 genes detected; for Templiphi, 67% of genes detected by gDNA were positive, with an extra 701 genes detected. These results indicate that MDA-based methods increase detection sensitivity for functional genes within bacterial communities. However, Bst aDNA showed fewer (51%) genes detected by gDNA, with an additional 85 genes detected. REPLI-g showed the highest number of different genes and the highest genome coverage (the percentage of genes detected in aDNA that were detected in gDNA). However, in considering the redundant genes (genes detected in aDNA but not in gDNA), REPLI-g and Templiphi showed higher numbers of redundant genes than Bst, and Bst showed the lowest percentage of redundant genes (number of redundant genes/number of genes detected in aDNA). REPLI-g and Bst showed similar representational biases, and both methods showed no genes whose hybridization signal ratios had more than a 1.5-fold difference, while Templiphi showed a higher representational bias than REPLI-g or Bst.

Table 2.

Results for whole-community genome DNA amplification obtained with the three MDA methods for the community sample, with or without sonication before Cy5 labeling

| Parameter |

Bst |

REPLI-g |

Templiphi |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With sonication | Without sonication | With sonication | Without sonication | With sonication | Without sonication | |

| No. of genes detecteda | 483 | 445 | 1,447 | 803 | 1,228 | 245 |

| No. of genes shared with gDNA | 398 | 373 | 714 | 601 | 527 | 165 |

| Average aDNA/gDNA ratiob | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 0.98 | 1.23 |

| Representational biasc | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.28 |

| F1.5d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.17 | 11.5 |

| F2.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.9 |

| F3.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Correlation with unamplified DNA (r)e | 0.753 | 0.759 | 0.856 | 0.910 | 0.590 | 0.380 |

Poor spots with SNRs [SNR = (signal − background)/SDbackground] of <2 were removed (SD, standard deviation). Single positive genes in 3 replicates and outliers of replicates (>3 times SD) were also removed. A total of 781 genes were detected in the gDNA sample.

The average ratio of signal intensity of aDNA to gDNA for each gene.

See Table 1, footnote e.

See Table 1, footnote g.

Correlation between aDNA and gDNA based on signal intensity.

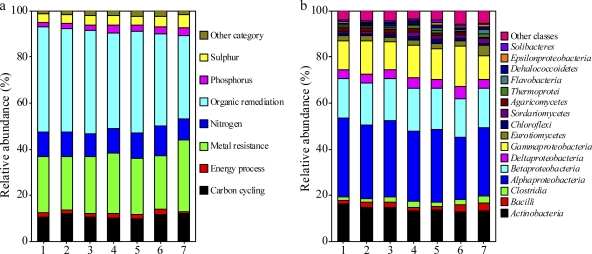

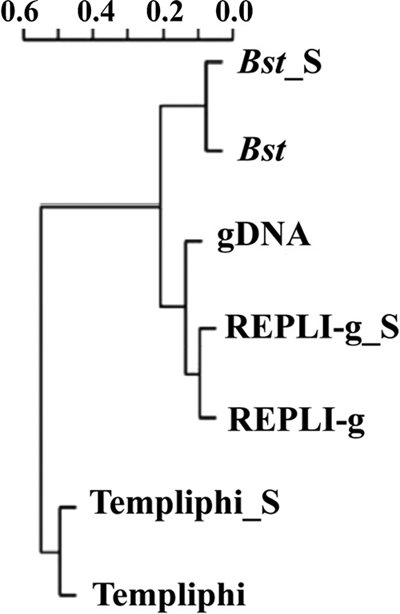

Sonication was tested to determine if this increased labeling efficiency; however, no significant difference in the amount of fluorescent dye incorporated (measured by Nanodrop; data not shown) was observed with or without sonication. While sonication after Bst and REPLI-g amplification appeared to reduce amplification bias, it also lowered gene detection. Sonication may break the complex structure of aDNA formed by MDA, resulting in more even labeling. At the same time, some information may be lost due to DNA breakage within ORFs. Sonication did not help reduce amplification bias for Templiphi, although the number of genes detected decreased dramatically. Cluster analysis of microarray data showed that aDNA amplified by the same method, with or without sonication, clustered together and that aDNA amplified with REPLI-g had a gene structure more similar to that of the gDNA than was seen for either Bst or Templiphi (Fig. 3). aDNA produced by all the MDA methods showed relative abundances in gene categories and phylogenetic profiles that were similar to the results for gDNA (Fig. 4), suggesting that it would be reliable to use an MDA-based microarray method for biological interpretation.

Fig. 3.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of amplified and unamplified community DNA based on GeoChip results. gDNA, unamplified DNA; Bst, amplified with Bst; Bst_S, amplified with Bst and sonicated before labeling; REPLI-g, amplified with REPLI-g; REPLI-g_S, amplified with REPLI-g and sonicated before labeling; Templiphi, amplified with Templiphi; Templiphi_S, amplified with Templiphi and sonicated before labeling.

Fig. 4.

Relative abundance of all functional gene categories (a) and microbial classes (b) detected by GeoChip in gDNA and aDNA. Relative abundance was calculated based on the gene number. Bars: 1, gDNA; 2, aDNA amplified with Bst; 3, aDNA amplified with Bst and sonicated before labeling; 4, aDNA amplified with REPLI-g; 5, aDNA amplified with REPLI-g and sonicated before labeling; 6, aDNA amplified with Templiphi; 7, aDNA amplified with Templiphi and sonicated before labeling.

The quantitation feasibility of microarray hybridization has been demonstrated, and good correlations of quantitation based on microarray hybridization and real-time PCR were obtained. For instance, a significant linear relationship (r2 = 0.96; P < 0.01) was observed between signal intensity and target DNA concentration within a concentration range of 60 to 1,000 ng with a 50-mer functional gene array (23). The expression of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 genes under different environmental stresses was evaluated with the whole-genome microarray, and the results were validated with real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. High correlations (r = 0.95 [n = 8] in reference 9; r2 = 0.91 [n = 7] in reference 19; r = 0.95 [n = 6] in reference 4; and r = 0.93 [n = 10] in reference 17) were obtained. For gene detection in community samples, Rhee et al. (21) used real-time PCR analysis with several representative genes and showed that the results of microarray-based quantification were very consistent with those of real-time PCR (r2 = 0.74 [n = 6]). He et al. (11) also showed that the gene copy number measured in a soil sample by quantitative real-time PCR was well correlated with the signal intensity detected by GeoChip 3.0 (r = 0.724 [n = 91], P = 0.0001). These results suggest that microarray hybridization data are consistent with real-time PCR data and, hence, that the microarray hybridization signals appear to be reliable.

Bst seems to have a lower requirement for DNA quality than phi29, as Bst DNA polymerase was shown to be effective in WGA of DNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues (1), while a restriction enzyme fragmentation step was needed for phi29 to amplify DNA derived from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue (25). We observed a higher success rate with Bst amplification than with either REPLI-g or Templiphi, especially when the DNA quality (i.e., absorbance ratios of 260/280 and 260/230) was low (data not shown), which may be an advantage for environmental samples. Bst has been used to amplify yeast, human, and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue DNA (1, 15). phi29 has been proven suitable for WGA of a single bacterium (20) and for microbial communities (26). phi29 provided more representational results than Bst for WGA of human DNA at the single-cell level, as judged by locus-specific PCR (22), while Bst was shown to be relatively unbiased compared to phi29 for yeast genome analysis by array comparative genome hybridization (15). However, all of these studies used DNA from single organisms. For individual genomes, all three MDA methods showed a high genome coverage and a relatively low amplification bias with pure culture DNA, as shown in this study. For complex microbial community samples, however, 10,000 genomes may be present in a single sample. Our previous study showed that the amount of DNA template would influence the representativeness of MDA products (26). Though we used 10× DNA template for MDA of the community sample, the MDA products for the community sample still showed less genome coverage than was the case for pure cultures. This increased complexity may explain why we observed such differences in representational bias using different MDA methods. The higher error rate of Bst may explain the lower gene detection and higher amplification bias, especially when the amount of template is limited (2). Though both kits are phi29-based, REPLI-g and Templiphi showed quite different results in WCGA. Templiphi was originally designed to amplify circular DNA, such as plasmids, while REPLI-g is designed for genomic DNA. The reaction buffer composition (e.g., random primer, dNTPs, enzyme concentration, and other assisting enzymes) may affect amplification results, as different phi29 commercial kits perform differently.

In conclusion, three MDA methods, Bst, REPLI-g, and Templiphi, were evaluated for use in WCGA of microbial DNA with microarrays in this study. The amplification biases of all methods were less than 3-fold. REPLI-g, a phi29-based kit, showed less bias and higher gene detection than the other two kits, while Bst had a higher success rate and might be more suitable for low-quality DNA. Sonication after WCGA by Bst and REPLI-g reduced the representational bias while also reducing gene detection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported through contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 (as part of ENIGMA, a Scientific Focus Area) and contract DE-SC0004601, from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, Genomics:GTL Foundational Science; by the United States Department of Agriculture (project 2007-35319-18305) through the NSF-USDA Microbial Observatories Program; and by the Tsinghua University Initiative Scientific Research Program (no. 2009THZ02238). J.W. was supported by the China Scholarship Council and the Natural Scientific Foundation of China (no. 40672162 and no. 40730738).

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, which greatly improved our manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 15 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aviel-Ronen S., et al. 2006. Large fragment Bst DNA polymerase for whole genome amplification of DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. BMC Genomics 7: 312 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-7-312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bergen A., Qi Y., Haque K., Welch R., Chanock S. 2005. Effects of DNA mass on multiple displacement whole genome amplification and genotyping performance. BMC Biotechnol. 5: 24 doi:10.1186/1472-6750-5-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blanco L., et al. 1989. Highly efficient DNA synthesis by the phage phi 29 DNA polymerase. Symmetrical mode of DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 264: 8935–8940 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chourey K., et al. 2006. Global molecular and morphological effects of 24-hour chromium(VI) exposure on Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72: 6331–6344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dean F. B., et al. 2002. Comprehensive human genome amplification using multiple displacement amplification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99: 5261–5266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dean F. B., Nelson J. R., Giesler T. L., Lasken R. S. 2001. Rapid amplification of plasmid and phage DNA using phi29 DNA polymerase and multiply-primed rolling circle amplification. Genome Res. 11: 1095–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eisen M. B., Spellman P. T., Brown P. O., Botstein D. 1998. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95: 14863–14868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. El Fantroussi S., et al. 2003. Direct profiling of environmental microbial populations by thermal dissociation analysis of native rRNAs hybridized to oligonucleotide microarrays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69: 2377–2382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gao H., et al. 2004. Global transcriptome analysis of the heat shock response of Shewanella oneidensis. J. Bacteriol. 186: 7796–7803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. He Z., et al. 2010. GeoChip 3.0 as a high-throughput tool for analyzing microbial community composition, structure and functional activity. ISME J. 4: 1167–1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. He Z., et al. 2010. Metagenomic analysis reveals a marked divergence in the structure of belowground microbial communities at elevated CO2. Ecol. Lett. 13: 564–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He Z., Zhou J. 2008. Empirical evaluation of a new method for calculating signal-to-noise ratio for microarray data analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74: 2957–2966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hong G.-F., Zhai F. May 1998. Bst DNA polymerase with proof-reading 3′-5′ exonuclease activity. U.S. patent 5,747,298 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hosono S., et al. 2003. Unbiased whole-genome amplification directly from clinical samples. Genome Res. 13: 954–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lage J. M., et al. 2003. Whole genome analysis of genetic alterations in small DNA samples using hyperbranched strand displacement amplification and array-CGH. Genome Res. 13: 294–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lasken R. S. 2007. Single-cell genomic sequencing using multiple displacement amplification. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10: 510–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leaphart A. B., et al. 2006. Transcriptome profiling of Shewanella oneidensis gene expression following exposure to acidic and alkaline pH. J. Bacteriol. 188: 1633–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pinard R., et al. 2006. Assessment of whole genome amplification-induced bias through high-throughput, massively parallel whole genome sequencing. BMC Genomics 7: 216 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-7-216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qiu X., et al. 2006. Transcriptome analysis applied to survival of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 exposed to ionizing radiation. J. Bacteriol. 188: 1199–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raghunathan A., et al. 2005. Genomic DNA amplification from a single bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71: 3342–3347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rhee S.-K., et al. 2004. Detection of genes involved in biodegradation and biotransformation in microbial communities by using 50-mer oligonucleotide microarrays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70: 4303–4317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spits C., et al. 2006. Optimization and evaluation of single-cell whole-genome multiple displacement amplification. Hum. Mutat. 27: 496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tiquia S. M., et al. 2004. Evaluation of 50-mer oligonucleotide arrays for detecting microbial populations in environmental samples. Biotechniques 36: 664–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Nostrand J. D., et al. 2009. GeoChip-based analysis of functional microbial communities during the reoxidation of a bioreduced uranium-contaminated aquifer. Environ. Microbiol. 11: 2611–2626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang G., et al. 2004. DNA amplification method tolerant to sample degradation. Genome Res. 14: 2357–2366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wu L., Liu X., Schadt C. W., Zhou J. 2006. Microarray-based analysis of subnanogram quantities of microbial community DNAs by using whole-community genome amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72: 4931–4941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu L., et al. 2004. Development and evaluation of microarray-based whole-genome hybridization for detection of microorganisms within the context of environmental applications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38: 6775–6782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang K., et al. 2006. Sequencing genomes from single cells by polymerase cloning. Nat. Biotechnol. 24: 680–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou J., Bruns M. A., Tiedje J. M. 1996. DNA recovery from soils of diverse composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62: 316–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou J., Fries M. R., Chee-Sanford J. C., Tiedje J. M. 1995. Phylogenetic analyses of a new group of denitrifiers capable of anaerobic growth on toluene and description of Azoarcus tolulyticus sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45: 500–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.