Abstract

Cigarette smoking is highly prevalent among patients who are being treated for opioid-dependence, yet there have been limited scientific efforts to promote smoking cessation in this population. Contingency management (CM) is a behavioral treatment that provides monetary incentives (available in the form of vouchers) contingent upon biochemical evidence of drug abstinence. This paper discusses the results of two studies that utilized CM to promote brief smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients. Participants in a pilot study were randomly assigned for a 2-week period to a Contingent group that earned monetary vouchers for providing biochemical samples that met criteria for smoking abstinence, or a Noncontingent group that earned monetary vouchers independent of smoking status (Dunn et al., 2008). Results showed Contingent participants provided significantly more smoking-negative samples than Noncontingent participants (55% vs. 5%, respectively). A second randomized trial that utilized the same 2-week intervention and provided access to the smoking cessation pharmacotherapy bupropion replicated the results of the pilot study (55% and 17% abstinence in Contingent and Noncontingent groups, respectively). A nonsignificant trend suggested bupropion may have contributed to smoking abstinence (Dunn et al, 2010). For both studies high rates of relapse to smoking were observed after the intervention ended; however, the results compare favorably to previous pharmacological and behavioral smoking cessation interventions and provide evidence that opioid-maintained patients can achieve a brief period of continuous smoking abstinence. Relapse to illicit drug use was also evaluated prospectively and no evidence that smoking abstinence was associated with a relapse to illicit drug use was observed (Dunn et al., 2009). It will be important for future studies to evaluate participant characteristics that might predict better treatment outcome, to assess the contribution that pharmacotherapies might have alone or in combination with a CM intervention on smoking cessation and to evaluate methods for maintaining the abstinence that is achieved during this brief intervention for longer periods of time.

Keywords: contingency management, smoking cessation, methadone, buprenorphine, smoking

Introduction

In the United States approximately 23.3% of the population are current cigarette smokers (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010). Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death, with over 467,000 deaths attributed to smoking annually (Danaei et al., 2009). Rates of cigarette smoking are particularly high among patients who are maintained on an opioid agonist (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine) for the treatment of opioid dependence. For example, 84-100% of methadone-maintained patients report being a current cigarette smoker (Clemmey, Brooner, Chutuape, Kidorf, & Stitzer, 1997; Haas et al., 2008; Nahvi, Richter, Li, Modali, & Arnsten, 2006; Richter, Gibson, Ahluwalia, & Schmelzle, 2001). As is true with the general population, cigarette smoking is associated with a variety of adverse health consequences in substance-dependent patients. When compared to people with no history of drug abuse, for example, substance abusers have an increased prevalence of smoking-related morbidity and mortality (Engstrom et al., 1991). Substance abusers are also more likely to die from smoking-related illness than problems related to drug and alcohol abuse (Hser et al., 1994; Hurt et al., 1996).

Rates of smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients are low. Only 5% of methadone-maintained patients exposed to a smoking cessation intervention were abstinent from smoking at a 6-month point-prevalence assessment (Shoptaw et al., 2002; Stein, Weinstock, et al., 2006), compared to 20% of smokers from the general population at a similar assessment period (Messer, Trinidad, Al-Delaimy, & Pierce, 2008). One possible explanation for the low rates of smoking cessation among methadone-maintained patients is evidence from laboratory and naturalistic studies that opioid agonists may increase the reinforcing effects of cigarettes (Bigelow, Stitzer, Griffiths & Liebson, 1981; Chait & Griffiths, 1984; Mello, Lukas & Mendelson, 1985; Mello, Mendelson, Sellers & Kuehnle, 1980; Mutschler, Stephen, Teoh, Mendelson & Mello, 2002; Richter et al., 2007; Schmitz, Grabowski & Rhoades, 1994; Story & Stark, 1991). The high prevalence of smoking, coupled with a potentially greater reinforcing value of cigarettes among opioid-maintained patients, suggests opioid-maintained smokers may be a particularly challenging group in which to promote smoking cessation.

Despite high rates of smoking, many opioid patients report knowledge of the adverse health consequences of smoking (Dunn, Sigmon, Reimann, Heil, & Higgins, 2009) and many patients report a desire to quit smoking (Clark, Stein, McGarry & Gogineni, 2001; Clemmey et al, 1997; Frosch, Shoptaw, Jarvik, Rawson & Ling, 1998; Kozlowski, Skinner, Kent & Pope, 1989; Richter et al., 2001; Sees & Clark, 1993). Survey studies have reported that approximately 70%-80% of opioid-maintained patients are interested in a smoking-cessation intervention, 68-75% have attempted to stop smoking at least once and 75% are willing to participate in a smoking-cessation program if one were made available in their methadone-maintenance clinic (Richter et al., 2001; Nahvi et al., 2006). Opioid treatment clinics may represent ideal settings in which to develop and implement a smoking cessation intervention. First, many patients become stable in treatment and can achieve prolonged periods of abstinence from illicit drug use, which may make them good candidates for a smoking intervention. Second, patients often attend the clinic on a regular basis (e.g., near daily) and remain engaged in treatment for extended periods, which can provide an opportunity to frequently monitor their smoking status. Third, many clinics adhere to a relatively uniform set of state and federal regulations. This suggests that a successful intervention, developed in the context of one clinic, may generalize well to other clinics that adhere to similar operating procedures. Fourth, data suggest that treatment programs that support smoking cessation can influence patients' likelihood of quitting (Knudsen & Studts, 2010; Richter, Choi, McCool, Harris, & Ahluwalia, 2004). For these reasons, a successful smoking-cessation intervention developed within the context of one program could have significant potential for dissemination to clinics throughout the country.

Thus far, there have been limited scientific efforts to develop smoking-cessation interventions among opioid-treatment patients, and study outcomes to date have been mixed. In this report, we briefly review the existing literature on smoking cessation among opioid-treatment patients and discuss some existing barriers in clinical efforts to promote smoking abstinence in this population. Next, we describe a program of research from our laboratory in which we have begun to address these issues, with the aim of developing an efficacious smoking intervention in this challenging population. Finally, we will discuss some potential directions for future research in this important area.

Barriers to successful smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients

Clinics do not emphasize smoking cessation

Few treatment clinics offer smoking cessation resources to patients, despite reports that many opioid-maintenance patients are interested in quitting smoking (Fuller et al, 2007; Knapp, Rosheim, Meister & Kottke, 1993; Olsen, Alford, Horton & Saitz, 2005; Richter, Choi & Alford, 2005). For example, only 48% of opioid-maintained patients report discussing smoking cessation with a counselor during their treatment. When counselors do provide advice, it generally consists of suggestions for how to quit smoking (73% of clinics surveyed), rather than structured smoking cessation counseling (32-41%) or administration of pharmacotherapies (17-29%; Friedmann, Jiang & Richter, 2008; Richter et al., 2004; Olsen et al., 2005; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010). Further, 30-40% of opioid-maintained patients report a counselor encouraged them to delay quitting smoking while receiving drug abuse treatment and 4% of patients had been encouraged to never attempt to quit smoking (Dunn et al., 2009; Richter, 2006; Richter, McCool, Okuyemi, Mayo & Ahluwalia, 2002).

Concern that smoking cessation will prompt illicit drug relapse

One barrier to smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients is a concern commonly cited by staff members in community clinics that smoking cessation will prompt a relapse to illicit drug use (Bobo, Slade & Hoffman, 1995; Guydish, Passalacqua, Tajima, & Manser, 2007). However, research suggests this fear is unsubstantiated. For example, studies that have monitored relapse to drug use following a smoking-cessation intervention generally report no change or a decrease in illicit drug or alcohol use following smoking cessation (Bobo, Gilchrist, Schilling, Noach & Schinke, 1987; Burling, Marshall & Seidner, 1991; Campbell, Wander, Stark & Holbert, 1995; Lemon, Friedmann & Stein, 2003; Prochaska, Delucchi & Hall, 2004; Reid et al., 2008; Shoptaw et al., 2002; Stapleton, Keaney & Sutherland, 2009). In addition, persistent smoking during drug treatment (as opposed to smoking cessation) has been proposed to be a useful indicator for identifying patients at risk for relapse to illicit drugs (Kohn, Tsoh & Weisner, 2003; Krejci, Steinberg & Ziedonis, 2003; Reid et al., 2008; Shoptaw et al., 2002).

Smoking cessation interventions among opioid-maintained patients

A number of interventions have evaluated smoking cessation pharmacotherapies or behavioral treatments to promote smoking abstinence among opioid-maintained patients. These interventions have yielded low to moderate abstinence rates.

Pharmacotherapy interventions

Smoking cessation pharmacotherapies (e.g., transdermal nicotine, bupropion) have produced low rates of smoking abstinence among opioid-maintained patients. The first of these studies was a nonrandomized evaluation of bupropion plus nicotine patch therapy administered to methadone-maintained smokers (Richter, McCool, Catley, Hall, & Ahluwalia, 2005). Participants (n=28) also received motivational interviewing to help them achieve smoking abstinence. Abstinence was defined as a breath carbon monoxide (CO) of ≤10ppm and self-report of no smoking in the previous 7 days. At the end of the 12-week treatment, only 7% of participants were classified as smoking abstinent. A second study provided methadone-maintained patients with a nicotine patch and motivational interviewing over a 12-week period (Stein, Weinstock et al., 2006). Participants (n=383) were randomly assigned to a minimal (patch + 2 counseling visits) or maximal (patch + 3 counseling visits) treatment group. Point-prevalence abstinence at 3 and 6 months was defined as a breath CO level of ≤8ppm. There was no significant effect of the intervention, with only 7% and 5% of all participants abstinent at the 3 and 6-month time-points, respectively. A third large-scale, multi-site trial included patients in methadone treatment and general outpatient treatment clinics (Reid et al., 2008). Participants were randomly assigned to receive a smoking intervention (n=153) or no intervention (n=72) while enrolled in their usual care drug-abuse treatment. Participants in the smoking intervention group received 8-weeks of nicotine patch and attended group cognitive-behavioral therapy. Breath CO samples were collected at each weekly visit and abstinence was defined as ≤10ppm. Participants who received the smoking intervention were more likely to provide a smoking-negative biochemical sample during Weeks 2-7 than those in the control group (10% vs. 0%, respectively), though overall rates of abstinence were modest and group differences were no longer evident at 13- and 26-week follow-ups.

Behaviorally-based interventions

The behavioral intervention contingency management (CM) has produced the greatest rates of smoking abstinence among opioid-maintained patients thus far. Contingency management is a behavioral approach wherein patients can earn monetary incentives (often in the form of vouchers) contingent upon providing objective evidence (e.g., biochemically-confirmed abstinence) of behavior change (Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, Badger & Higgins, 2006). CM interventions have been effective in promoting abstinence from a range of illicit drugs (Higgins, Silverman & Heil, 2008), and have shown efficacy for promoting smoking cessation as well (see Sigmon, Lamb & Dallery, 2008 for review).

The first examination of a CM intervention to promote smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients was a laboratory study (Schmitz, Rhoades & Grabowski, 1995). This study utilized an A-B-A-B design wherein smoking among 5 methadone-maintained participants was monitored during A phases and smoking abstinence was reinforced during B phases. Each phase lasted 2 weeks and smoking was monitored twice weekly throughout the study. During B phases, money was available contingent upon a breath CO sample that was a >50% reduction of the mean samples collected during the preceding A phase and $5 vouchers were available for abstinent samples during the B phase (maximum earnings: $40). The study found no significant decrease in CO levels during the contingent phase, with mean CO levels never decreasing below 8ppm, the cutoff recommended to define smoking abstinence (SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002).

CM was next evaluated in a nonrandomized pilot study with 17 methadone-maintained patients (Shoptaw, Jarvik, Ling & Rawson, 1996). Patients provided breath CO samples thrice weekly over a 4-week period. Abstinence was defined as CO ≤4 ppm and vouchers were provided on an escalating schedule (Higgins et al., 1991), beginning at $2.50 and increasing by $0.50 with each subsequent negative sample (maximum earnings: $73.00). Twenty-four percent of participants provided ≥3 samples that met the abstinence criterion (representing one week of meeting the abstinence criterion), though all participants had resumed smoking by the end of the intervention. This effort was followed by a more rigorous clinical trial (n=175) evaluating the use of CM and relapse prevention for smoking cessation among methadone-maintained smokers (Shoptaw et al., 2002). In this 12-week trial, participants were randomly assigned to one of four groups: control, CM, relapse prevention or CM + relapse prevention. Participants in all four groups also received the nicotine patch as a platform pharmacotherapy and provided breath CO samples thrice weekly, with abstinence defined as a CO of ≤8ppm. CM participants earned vouchers for each negative sample on an escalating schedule that began at $2.00 and increased with each subsequent negative sample by $0.50 (maximum earnings: $447.50). Relapse prevention participants were required to attend standardized group counseling. Results showed abstinence was significantly greater among participants in the two CM groups (nicotine patch + CM, nicotine patch+ CM + relapse prevention), suggesting a positive contribution from the CM component; however, no group differences persisted at 6- or 12-month follow-ups.

A recent attempt to use CM to promote smoking cessation was conducted with participants entering an outpatient buprenorphine clinic (Mooney et al., 2008). The primary focus of this study was bupropion vs. placebo for smoking cessation and CM was provided to all participants over a 10-week period to encourage abstinence. Participants (n=40) began buprenorphine maintenance and smoking cessation treatment simultaneously and received motivational counseling + CM to promote abstinence from cigarettes, opioids and cocaine. Participants attended the clinic 5 times per week and breath and urine samples were collected thrice weekly. Smoking abstinence was defined as a breath CO of <10ppm and urine samples were tested for evidence of opioids and cocaine. At each visit participants were required to meet the abstinence criteria for cigarettes, opioids and cocaine to earn a $5.00 voucher, with a total maximum earning potential of $150. Results showed no significant differences in smoking abstinence between the bupropion and placebo groups (13.7% vs. 11.4%, respectively), and no differences in the frequency of opioid or cocaine-positive samples. Self-report of smoking decreased over time in both groups however no significant reduction in CO values was observed. Although this study represented the first effort to reduce smoking among buprenorphine patients, it is important to note that CM was not experimentally evaluated.

Changes to CM methodology that may improve smoking abstinence outcomes

Although these studies provide support for using CM to promote smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients, the low rates of smoking abstinence suggest opioid-maintained patients may require an intensive intervention in order to achieve smoking abstinence. Several characteristics of the CM interventions used in these trials can be modified to produce more smoking abstinence. First, a more frequent schedule of monitoring and reinforcement of abstinence during the initial days and weeks of the intervention may increase abstinence. For example, as previously described, biochemical samples were generally collected 2-3 times weekly, however, opioid-maintained patients often report to the treatment clinic daily or near-daily and can be therefore be monitored more frequently than 2-3 times weekly. Intensive monitoring of abstinence during the initial part of a quit attempt is important due to the high rate of smoking relapse that occurs during this time (e.g., Hughes et al., 1992). It also provides an opportunity to more frequently reinforce smoking abstinence. Second, the studies described above generally used a CO cutpoint of ≤ 8 ppm. Although 8ppm is a commonly-used and recommended cutoff in smoking-cessation research (SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002), recent research suggests this cutoff may allow low-level or intermittent smoking to persist undetected (Cropsey, Eldridge, Weaver, Villalobos, & Stitzer, 2006; Javors, Hatch, & Lamb, 2005; Raiff, Faix, Turturici, & Dallery, 2010). Given the evidence that early and sustained abstinence is associated with long-term abstinence, these details may determine the longer-term success of the intervention.

Current research on smoking cessation in opioid-maintained patients

A brief behavioral intervention can promote brief smoking cessation

We have conducted a series of randomized trials investigating procedures to promote smoking abstinence among opioid-maintained patients over a brief two week intervention. The goals of these studies were to address the limitations of previous studies (as described above) and to increase the number of opioid-maintained patients who achieved smoking abstinence.

We first conducted a pilot study aimed at promoting brief smoking abstinence among opioid-maintained patients (Dunn et al., 2008). A 2-week study duration was chosen because research has shown smoking abstinence achieved during the initial two weeks of a quit attempt is a robust predictor of long-term abstinence in both non-methadone-maintained (Gourlay, Forbes, Marriner, Pethica & McNeil, 1994; Higgins et al., 2006; Kenford et al., 1994; Yudkin, Jones, Lancaster & Fowler, 1996) and methadone-maintained (MM) populations (Frosch, Nahom & Shoptaw, 2002). Recruitment materials were distributed in a local methadone clinic. Eligible participants had to self-report smoking ≥ 10 cigarettes a day for ≥ 1 year and be maintained on a stable methadone dose for the past 30 days. Illicit opioid and cocaine use have been shown to directly increase smoking rates (Chait & Griffiths, 1984; Higgins et al., 1994; Mello et al., 1980; Mello et al., 1985; Roll, Higgins & Tidey, 1997; Schmitz et al., 1994), therefore participants were required to have low level illicit opioid and cocaine use (< 30% positive specimens) during the past 30 days to participate. Twenty MM smokers participated in the 2-week study. On average (±SEM), participants were 30 ± 8.1 years old, 40% male and had completed 12 ± 1.6 years of education. Participants smoked an average of 19 ± 6.3 cigarettes a day, had smoked cigarettes for 13 ± 8 years, were maintained on 106 ± 43.7 mg of methadone daily, and had been on the same methadone dose for approximately 88 ± 100 days.

Throughout the 2-week study, all participants visited the clinic daily and provided breath and urine samples at each visit for biochemical verification of smoking status. On Study Days 1-5, smoking abstinence was defined as a breath CO of ≤ 6 ppm. Beginning on Study Day 6 and continuing for the remainder of the 14-day study, abstinence was defined as a urinary cotinine level of ≤ 80 ng/ml. CO monitoring is sensitive to recent smoking behavior and sets the occasion for reinforcement for initial quitting. Cotinine is a metabolite of nicotine that is detectable in urine and has a longer half-life (16 hours) than CO (2-3 hours), which allows for it to be detected for multiple days after exposure to a cigarette (SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002). We believe utilizing this combination of biochemical measures as criteria for abstinence permits us to reinforce early smoking abstinence (e.g., CO phase) while also placing a contingency on long-term smoking abstinence (e.g., cotinine phase). Participants were randomly assigned to Contingent (n=10) or Noncontingent (n=10) experimental groups. Contingent participants earned vouchers contingent upon submitting biochemical samples that met the abstinence criteria. Voucher values began at $9 and increased by $1.50 with each consecutive negative sample. To further promote early and continuous smoking abstinence, a $10.00 bonus was made available during Study Days 1-5 to participants who provided a CO sample ≤4 ppm, and a $50 bonus was provided on Day 6 to participants who provided a cotinine sample ≤80 ng/ml. Using this schedule, Contingent participants could earn a maximum of $362.50 in vouchers for continuous abstinence during the 14-day study. Participants in the Noncontingent control group received vouchers independent of smoking status and were yoked to an individual in the Contingent condition, with a maximum earning potential of $362.50 during the study. Vouchers for both groups were redeemable for goods and services from local stores; participants received no cash and research staff made all purchases.

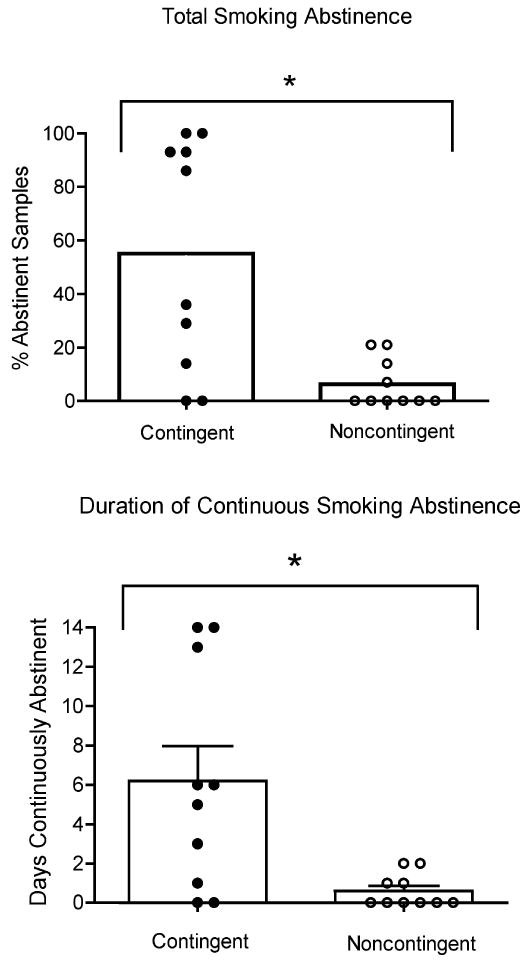

Contingent participants achieved significantly more smoking abstinence than Noncontingent participants, as evidenced by more smoking-negative samples (55% vs. 5%, p <.01; Figure 1, top panel) and longer durations of continuous smoking abstinence (6.3 vs. 0.6 days, p=.01; Figure 1, bottom panel), respectively. The favorable smoking outcomes among Contingent participants were evident across all measures of smoking throughout the study, including breath CO levels, urine cotinine levels, and self-reported number of cigarettes smoked. Overall, data from this pilot study provided initial support for the efficacy of a brief yet intensive CM intervention in producing brief smoking abstinence among methadone-maintenance patients.

Figure 1.

Total smoking abstinence (top panel) and longest duration continuous smoking abstinence (bottom panel) for 20 opioid-maintained patients. Bars represent group means and circles represent individual data. Asterisk represents significance at p<05 level, vertical bar represents SEM. Reprinted with permission from: Dunn, K.E., Sigmon, S.C. Thomas, C.S., Heil, S.H., & Higgins, S.T. (2008). Voucher-based contingent reinforcement of smoking abstinence among methadone-maintained patients: A pilot study. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, Vol. 41 (4), pp 527-538.

A subsequent randomized clinical trial was conducted to replicate and extend our pilot findings (Dunn et al., 2010). The methods of this study were identical to those described above for the pilot study; however, the intervention was expanded in three important ways. First, we recruited a larger sample size than the pilot study, with 40 opioid-maintained smokers randomly assigned to Contingent (n=20) or Noncontingent (n=20) experimental groups. Second, we recruited both methadone and buprenorphine-maintained patients in our study sample. Finally, participants were offered bupropion (Zyban®) if they were medically eligible to receive the pharmacotherapy. Although not a primary focus of this research, pharmacotherapies such as nicotine replacement and bupropion are generally considered first-line treatments for smoking (Fiore et al., 2008). Considering the high prevalence of smoking and smoking-related morbidity and mortality among opioid-maintained patients, we believed it was important to offer as many tools as possible to support smoking cessation in this population and nicotine replacement was precluded due to our reliance on urinary cotinine testing. Bupropion was offered to all participants and was stratified across the two experimental groups to ensure equal distribution. However bupropion administration was not mandated or placebo-controlled. Mandating bupropion administration for study participation would likely have excluded up to 50% of potential participants from participating due to disinterest in bupropion or medical contraindications (Richter et al., 2005).

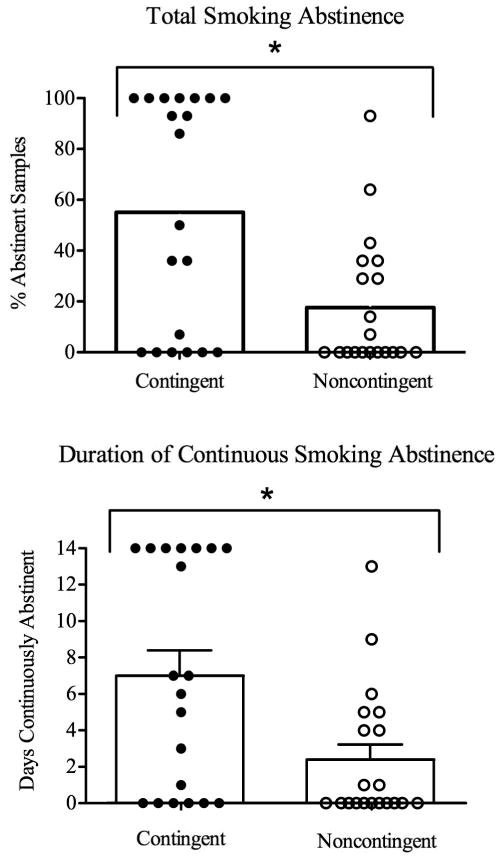

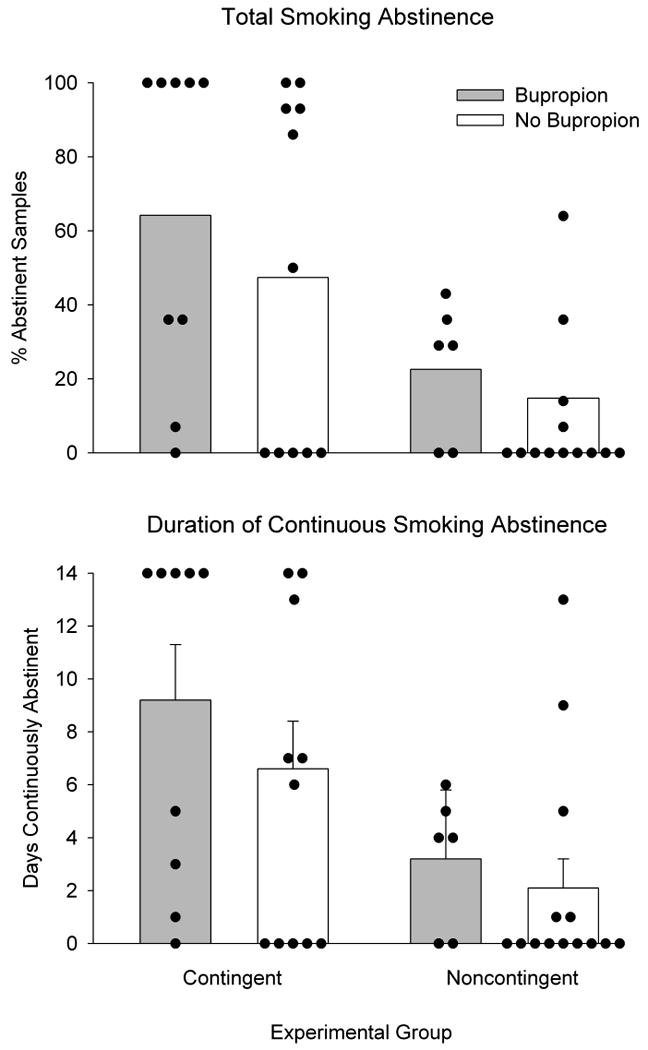

Participants were, on average (SEM), 31.0 ± 1.8 years old, 33% male and had completed 12.5 ± 0.3 years of education. Participants smoked an average of 18.5 ± 1.8 cigarettes a day, had smoked cigarettes for 10.9 ± 1.3 years, were maintained on 107.6 ± 8.8 and 14.9 ± 1.3 methadone and buprenorphine, respectively, and had been on the same maintenance dose for 171.8 ± 48.2 days. Nine (45%) and six (30%) participants from the Contingent and Noncontingent groups used bupropion, respectively. Results replicated those of the pilot study. Contingent participants provided significantly more samples that met the abstinence criteria than Noncontingent (55% and 17%, respectively, p<0.01; Figure 2, top panel) and were abstinent for longer continuous durations than Noncontingent participants (7.7 and 2.4 days, respectively, p<0.01; Figure 2, bottom panel). Although there was a trend towards better abstinence outcomes among participants taking bupropion, bupropion did not contribute significantly to percent smoking abstinence (p=0.33; Figure 3, top panel) or longest duration continuous abstinence (p=0.28; Figure 3, bottom panel). Results from this randomized clinical trial provided further support for the efficacy of CM in promoting smoking abstinence in this hard-to-treat population.

Figure 2.

Total smoking abstinence (top panel) and longest duration continuous smoking abstinence (bottom panel) for 40 opioid-maintained patients. Bars represent group means and circles represent individual data. Asterisk represents significance at p<05 level, vertical bar represents SEM. Reprinted with permission from: Dunn, K.E., Sigmon, S.C., Reimann, E.R., Badger, G.J., Heil, S.H., & Higgins, S.T. (2010). A contingency-management intervention to promote initial smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, Vol. 18 (1), pp 37-50.

Figure 3.

Total smoking abstinence (top panel) and longest duration continuous smoking abstinence (bottom panel) for 40 opioid-maintained patients, as a function of bupropion (gray bars) or no bupropion (white bars). Bars represent group means and circles represent individual data. Vertical bars represent SEM.

Association between smoking abstinence and relapse to illicit drug use

We also evaluated whether opioid-maintained smokers who achieved smoking abstinence during our brief intervention would provide a greater number of drug-positive urine samples than participants who did not achieve abstinence (Dunn, Sigmon, Reimann, Heil & Higgins, 2009). Urine samples were collected daily and analyzed for evidence of opiates, oxycodone, propoxyphene, cocaine, amphetamine, benzodiazepines and cannabis. Results showed no group differences in the frequency of positive urine samples, with participants providing extremely low (e.g., 1-4%) numbers of drug-positive urines (Dunn et al., 2009). Overall, we found no evidence that smoking abstinence undermined illicit drug abstinence within opioid-maintained patients. These findings lend support for treatment programs to encourage smoking cessation among patients who are stable in their drug abuse treatment.

Limitations of the current studies

Some limitations of these studies should be noted. First, participants were required to be stable on their opioid agonist dose and generally abstinent from illicit drugs in order to participate in these studies, which may limit the generality of our findings to unstable patients. However, we do not believe this is not a significant concern, since many opioid-maintained patients become stable and abstinent from illicit drugs for long periods and these individuals may be the best candidates for making a quit attempt during treatment. For example, in the Dunn et al (2010) study, only 15% of patients who were interested in participating were excluded for failure to meet the eligibility requirements related to stable dose and drug abstinence. This data suggests that the majority of people who were interested in participating in the smoking cessation intervention were eligible. It will be important in future studies to determine whether smoking abstinence can be achieved with participants who are less stable in treatment.

Second, our intervention was brief and the majority of participants resumed smoking after the contingencies were removed. We did not expect that a 2-week intervention with no additional abstinence-reinforcement period would be sufficient to produce long-term smoking abstinence. However, we do believe these studies provide an important demonstration that opioid-maintained patients can achieve high rates of smoking abstinence for a continuous, albeit brief, period of time. These findings provide support for additional research on the use of CM interventions to promote smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients, though it is clear that additional studies are needed to investigate methods for maintaining the abstinence that is achieved during an initial 2-week period.

Discussion

Summary of Current Findings

Smoking Abstinence

Patients enrolled in treatment for opioid dependence continue to smoke at disproportionately higher rates than the general population, and this smoking is related to increased smoking-related morbidity and mortality (Engstrom et al., 1991; Hser et al., 1994; Hurt et al., 1996). Although a high percentage of these patients report an interest in quitting smoking, there has been limited research on how to help them successfully achieve abstinence. Review of previous interventions reveal CM has produced the highest rates of smoking abstinence in this population thus far. The current studies extend upon this literature by evaluating the use of CM to promote a brief but continuous period of smoking abstinence. Participants in these studies who received vouchers contingent upon biochemical verification of smoking abstinence achieved significantly greater amounts and durations of smoking abstinence than control participants (Dunn et al., 2008; Dunn et al., 2010). These data are promising and provide support for the use of CM in promoting initial smoking abstinence among patients enrolled in opioid maintenance treatment. It is important that additional research be conducted to identify methods for extending the initial smoking abstinence that is evident following these brief interventions.

Changes to CM methodology

The methodology of the current studies differed in several ways from previous CM interventions. First, the frequency of biochemical monitoring was increased from 2-3 times per week in the previous studies to daily in the current studies (Schmitz et al., 1995; Shoptaw et al., 1996, Shoptaw et al., 2002). Increasing the frequency of visits provides more opportunities to reinforce smoking abstinence and gain control over the target behavior.

Second, although prior studies relied primarily on breath CO as an indicator of smoking status, the current studies utilized both CO and cotinine. CO is a good measure of acute smoking status; however, its relatively short half-life (e.g., 2-3 hours; SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002), in combination with the low frequency of monitoring utilized in previous studies, can allow participants to smoke at low levels and still potentially meet a breath CO cutpoint. In contrast, the extended half-life of urinary cotinine (16 hours) allows it to be detected for several days after cigarette exposure (16 hours; SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002). Therefore, the use of urinary cotinine as an indicator of abstinence can increase the likelihood that even low-level smoking is detected and may be particularly valuable for interventions that do not require daily monitoring. In addition to utilizing multiple measurements for verifying abstinence, the current studies also employed stricter cutpoints than those used in previous studies. The increased frequency of monitoring, in combination with stricter biochemical measurements, may have prevented less undetected smoking from occurring, and therefore allowed for more frequent reinforcement of the target behavior. This is important because previous research has suggested that narrowly defining a target behavior and increasing the frequency of its measurement can strengthen the relationship between the target behavior (e.g., smoking) and its consequences (e.g., receiving a voucher incentive) (Higgins et al., 2008; Petry, 2000).

Finally, participants in the current studies were eligible to earn a greater magnitude of voucher-based incentives than those provided in current studies. For example, while participants in the current studies were eligible to earn high magnitude voucher-based incentives ($181.25/week and a total of $362.50 over the 2-week study) for evidence of smoking abstinence, potential earnings in previous CM studies only averaged around $18.63/week (range: $4.00 - $37.29). When the magnitude of a reinforcer (e.g., a voucher-based incentive) is too low, CM interventions may lose some of their effectiveness. This may be due, in part, to an inability of the reinforcer to compete with the reinforcing effects of drug use. Notably, magnitude of voucher earnings has been shown to influence abstinence from illicit drugs (Higgins et al., 2007; Lussier et al., 2006; Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 1999; Stitzer & Bigelow, 1984) and may have contributed to the favorable outcomes observed in the current study.

These modifications may have contributed to the increased rate of smoking abstinent samples provided in the current studies. However, it is important to note that the added value of these modifications may not be limited to CM interventions. For example, increasing the frequency and/or sensitivity of biochemical monitoring could potentially lead to increased rates of smoking abstinence in non-CM smoking cessation interventions as well. Further research that identifies how changes in CM methodologies might contribute to overall treatment outcomes is needed. This research may also provide important information on what components of a smoking cessation intervention are both necessary and sufficient to promote continued smoking abstinence within an opioid-maintained population.

Relapse to illicit drug use

We evaluated a commonly-cited concern that smoking cessation among patients being treated for substance dependence will be associated with a relapse to illicit drug use (Campbell et al., 1995; Hahn, Warnick & Plemmons, 1999). Interestingly, 50% of the participants in the Dunn et al (2010) study reported a drug counselor had advised them to delay quitting smoking. This report is consistent with surveys of methadone clinics wherein treatment staff report reluctance to encourage smoking cessation, due to fear it will prompt illicit drug relapse among patients (Richter, 2006; Richter et al., 2002). There was no evidence from the present studies that smoking cessation promoted a relapse to illicit drug use. This finding is consistent with results from several prior smoking interventions within opioid-maintained (Reid et al., 2008, Shoptaw et al., 2002) and non-opioid-maintained substance abuse treatment populations (Bobo et al., 1987; Campbell et al., 1995; Prochaska et al., 2004). The ability of CM to experimentally produce either high rates of smoking abstinence (largely in the Contingent group) or low rates of smoking abstinence (e.g., Noncontingent group) in a prospectively randomized sample of opioid-maintained smokers provided an opportunity to directly compare rates of illicit drug use between these two experimental conditions and replicates the results of previous studies using a more experimentally rigorous methodology. The lack of evidence that quitting smoking undermines illicit drug abstinence lends support for programs to encourage smoking cessation among patients stable in their substance abuse treatment.

Additional challenges with promoting smoking abstinence among opioid-maintained patients

Although the current studies demonstrate the efficacy of a brief intensive behavioral intervention to produce smoking abstinence among opioid-maintained patients, there are still several challenges that need to be met.

Individual differences in treatment response

As seen in Figures 1 and 2 there were marked differences across individuals in response to the interventions, with participants achieving either near-complete smoking abstinence or low to moderate levels of smoking abstinence. We were unable to identify any demographic or drug use characteristics that reliably predicted an individual's response to our CM smoking-cessation intervention (Dunn et al., 2008; Dunn et al., 2010), despite reports that lower nicotine dependence is associated with better smoking outcomes (Fagerström & Schneider, 1989; Heatherton et al., 1989; John, Meyer, Rumpf & Hapke, 2004; Lerman et al., 2004). Our inability to identify predictors of treatment response may be due to the relatively limited sample sizes employed in these studies. It will be important for future studies to continue evaluating whether any participant demographic, drug use or smoking characteristics might predict a more favorable response to this smoking cessation intervention.

Limited response to pharmacological intervention

As seen in Figure 3, participants who received bupropion provided more samples that met the abstinence criteria than those who did not receive bupropion; however, this finding did not reach statistical significance. Bupropion did result in significant reductions on several self-report items related to nicotine withdrawal (data not shown) that are consistent with studies conducted in non-opioid dependent populations (Gonzales et al., 2006; Jorenby et al., 2006; Shiffman et al., 2000; West, Baker, Cappelleri, & Bushmakin, 2008). These data suggest that participants did receive some expected and positive effects from bupropion. However, the lack of a significant bupropion effect on smoking abstinence itself is inconsistent with the literature on the use of bupropion on non-opioid maintained individuals, wherein bupropion can approximately double the odds of quitting smoking (Hughes et al., 2009). Our data are consistent with several pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation within opioid-maintained patients. For example, bupropion did not significantly contribute to smoking abstinence in two prior studies with stable opioid-maintained patients (Mooney et al., 2008; Richter et al., 2005), and nicotine replacement therapy has also traditionally failed to impact smoking outcomes in this population (Shoptaw et al., 2002; Stein, Anderson & Niaura, 2006, Stein et al., 2006). Taken together, these data suggest that pharmacotherapies may not exert their usual effects on smoking behavior within opioid-dependent patients. It is also possible, however, that our study lacked a sufficient sample size to detect the contribution of bupropion to smoking cessation outcomes.

In general, there are limited data on the effectiveness of administering bupropion in combination with a CM intervention for smoking cessation. One randomized, placebo-controlled study evaluated the combined effect of CM and bupropion on smoking behavior in non-opioid maintained adolescents (Gray et al., 2010). These researchers reported greater smoking abstinence among participants receiving CM + bupropion when compared to participants receiving either intervention alone. Though nonsignificant, the results of the Dunn et al., (2010) study also suggest a potential additive effect of bupropion when combined with a CM intervention. Together these data highlight the need for a large scale clinical trial to rigorously evaluate the added benefit of a combined CM and pharmacotherapy intervention for smoking cessation.

High rates of relapse to smoking

Although these studies were successful in promoting initial smoking cessation in a high percentage of participants, a high rate of relapse to smoking following completion of this brief intervention was observed (Dunn et al., 2008; Dunn et al., 2010). The lack of persistent abstinence effects is likely due to the brevity of the intervention and the removal of the contingencies. Although the duration of the current intervention (e.g., 2 weeks) was chosen due to evidence that cigarette abstinence achieved in the initial 2-weeks of a quit attempt was associated with long-term cigarette abstinence (Frosch et al., 2002; Gourlay et al., 1994; Higgins et al., 2006; Kenford et al., 1994; Yudkin et al., 1996), the high rate of relapse observed following completion of the current studies suggests that an intensive 2-week intervention is not sufficient to promote long-term smoking abstinence among opioid-maintained patients. The fact that smoking resumed following completion of the intervention is not entirely surprising, however, as we know of no efficacious 2-week smoking cessation intervention among opioid and non opioid-maintained smokers. The current studies did demonstrate that a CM smoking cessation intervention among opioid-treatment patients can produce high rates of smoking abstinence over a brief period of time. The next step is to identify whether this initial smoking abstinence can be maintained over a longer period of time using a longer-duration CM intervention. We are currently conducting a 12-week randomized clinical trial to experimentally investigate this question.

Conclusions

In conclusion, prevalence of cigarette smoking among opioid-treatment patients is three-fold that of the general population and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. There have been few attempts, and limited success, to promote smoking abstinence in this population. The current studies demonstrate the efficacy of a brief voucher-based CM intervention in promoting initial smoking abstinence among opioid-maintained patients. Additional research is needed to identify methods for sustaining the smoking abstinence that is achieved during this initial intervention. Overall, this line of research has important implications for opioid-maintained populations, as well as other drug treatment modalities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Edward Reimann for his assistance in completing these studies, Sarah Heil and Stephen Higgins for assistance in designing the studies and Colleen Thomas and Gary Badger for their statistical assistance. This research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), R01 DA019550 (Sigmon) and T32 DA007242.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/PHA

References

- Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML, Griffiths RR, Liebson IA. Contingency management approached to drug self-administration and drug abuse: efficacy and limitations. Addictive Behaviors. 1981;6(3):241–252. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(81)90022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK, Gilchrist LD, Schilling RF, Noach B, Schinke SP. Cigarette smoking cessation attempts by recovering alcoholics. Addictive Behaviors. 1987;12(3):209–215. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK, Slade J, Hoffman AL. Nicotine addiction counseling for chemically dependent patients. Psychiatric Services. 1995;46(9):945–947. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.9.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burling TA, Marshall GD, Seidner AL. Smoking cessation for substance abuse inpatients. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1991;3(3):269–276. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(10)80011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burling TA, Ziff DC. Tobacco smoking: a comparison between alcohol and drug abuse inpatients. Addictive Behaviors. 1988;13(2):185–190. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(88)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BK, Wander N, Stark MJ, Holbert T. Treating cigarette smoking in drug-abusing clients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1995;12(2):89–94. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)00002-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chait LD, Griffiths RR. Effects of methadone on human cigarette smoking and subjective ratings. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1984;229(3):636–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JG, Stein MD, McGarry KA, Gogineni A. Interest in smoking cessation among injection drug users. The American Journal on Addictions. 2001;10(2):159–166. doi: 10.1080/105504901750227804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmey P, Brooner R, Chutuape MA, Kidorf M, Stitzer M. Smoking habits and attitudes in a methadone maintenance treatment population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;44(2-3):123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cropsey KL, Eldridge GD, Weaver MF, Villalobos GC, Stitzer ML. Expired carbon monoxide levels in self-reported smokers and nonsmokers in prison. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2006;8(5):653–659. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, Taylor B, Rehm J, Murray CJ, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(4):e1000058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KE, Sigmon SC, Reimann E, Badger GJ, Heil S, Higgins ST. A contingency-management intervention to promote initial smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18(1):37–50. doi: 10.1037/a0018649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KE, Sigmon SC, Reimann E, Heil SH, Higgins ST. Effects of smoking cessation on illicit drug use among opioid-maintained patients: A pilot study. Journal of Drug Issues. 2009;39(2):313–328. doi: 10.1177/002204260903900205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KE, Sigmon SC, Thomas CS, Heil SH, Higgins ST. Voucher-based contingent reinforcement of smoking abstinence among methadone-maintained patients: A pilot study. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41(4):527–538. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom A, Adamsson C, Allebeck P, Rydberg U. Mortality in patients with substance abuse: a follow-up in Stockholm County, 1973-84. International Journal of Addictions. 1991;26(1):91–106. doi: 10.3109/10826089109056241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström KO, Schneider NG. Measuring nicotine dependence: A review of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1989;12:159–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00846549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz N, Curry SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Jiang L, Richter KP. Cigarette smoking cessation services in outpatient substance abuse treatment programs in the United States. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34(2):165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch DL, Nahom D, Shoptaw S. Optimizing smoking cessation outcomes among the methadone maintained. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23(4):425–430. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch DL, Shoptaw S, Jarvik ME, Rawson RA, Ling W. Interest in smoking cessation among methadone maintained outpatients. Journal of Addictive Disorders. 1998;17(2):9–19. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller BE, Guydish J, Tsoh J, Reid MS, Resnick M, Zammarelli L, et al. Attitudes towards the integration of smoking cessation treatment into drug abuse clinics. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, et al. Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296(1):47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlay SG, Forbes A, Marriner T, Pethica D, McNeil JJ. Prospective study of factors predicting outcome of transdermal nicotine treatment in smoking cessation. British Medical Journal. 1994;309(6958):842–846. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6958.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray KM, Carpenter MJ, Baker NL, Hartwell KJ, Lewis AL, Hiott DW, et al. Bupropion SR and contingency management for adolescent smoking cessation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.08.010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Tajima B, Manser ST. Staff smoking and other barriers to nicotine dependence intervention in addiction treatment settings: a review. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39(4):423–433. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Sorenson JL, Hall SM, Lin C, Delucchi K, Sporer K, et al. Cigarette smoking in opioid-using patients presenting for hospital-based medical services. American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17(1):65–69. doi: 10.1080/10550490701756112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn EJ, Warnick TA, Plemmons S. Smoking cessation in drug treatment programs. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 1999;18:89–101. doi: 10.1300/J069v18n04_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84(7):791–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Bickel WK, Lynn M, Mortensen A. Influence of cocaine use on cigarette smoking. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272(22):1724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Delaney DD, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Foerg F, et al. A behavioral approach to achieving initial cocaine abstinence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148(9):1218–1224. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.9.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Dantona R, Donhman R, Matthews M, Badger GJ. Effects of varying monetary value of voucher-based incentives on abstinence achieved during and following treatment among cocaine-dependent outpatients. Addiction. 2007;102(2):271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Dumeer AM, Thomas CS, Solomon LJ, Bernstein IM. Smoking status in the initial weeks of quitting as a predictor of smoking-cessation outcomes in pregnant women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;85(2):138–141. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH, editors. Contingency management in substance abuse treatment. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, McCarthy WJ, Anglin MD. Tobacco use as a distal predictor of mortality among long-term narcotic addicts. Preventative Medicine. 1994;23(1):61–69. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Gulliver SB, Fenwick JW, Valliere WA, Cruser K, Pepper S, et al. Smoking cessation among self-quitters. Health Psychology. 1992;11:331–334. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.5.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub3. Art. No. CD000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Gomez-Dahl L, Kottke TE, Morse RM, et al. Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment: role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275(14):1097–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.14.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javors MA, Hatch JP, Lamb RJ. Cut-off levels for breath carbon monoxide as a marker for cigarette smoking. Addiction. 2005;100(2):159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John U, Meyer C, Rumpf HJ, Hapke U. Smoking, nicotine dependence and psychiatric comorbidity- a population-based study including smoking cessation after three years. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76(3):287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, et al. Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group. Efficacy of varenicline, a alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296(1):56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenford SL, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Wetter D, Baker TB. Predicting smoking cessation: Who will quit with and without the nicotine patch. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271(8):589–594. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.8.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp JM, Rosheim CL, Meister EA, Kotttke TE. Managing tobacco dependence in chemical dependency treatment facilities: a survey of current attitudes and policies. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 1993;12(4):89–104. doi: 10.1300/J069v12n04_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Studts JL. The implementation of tobacco-related brief interventions in substance abuse treatment: a national study of counselors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38(3):212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn CS, Tsoh JY, Weisner CM. Changes in smoking status among substance abusers: baseline characteristics and abstinence from alcohol and drugs at 12-month follow-up. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69(1):61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Skinner W, Kent C, Pope MA. Prospects for smoking treatment in individuals seeking treatment for alcohol and other drug problems. Addictive Behavior. 1989;14(3):273–278. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci J, Steinberg ML, Ziedonis D. Smoking status and substance abuse severity in a residential treatment sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;72(3):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon SC, Friedmann PD, Stein MD. The impact of smoking cessation on drug abuse treatment outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28(7):1323–1331. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Kaufmann V, Rukstalis M, Patterson F, Perkins K, Audrain-McGovern J, et al. Individualizing nicotine replacement therapy for the treatment of tobacco dependence: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140(6):426–433. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-6-200403160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GA, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101(2):192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH. Buprenorphine effects on cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology. 1985;86:417–425. doi: 10.1007/BF00427902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Sellers ML, Kuehnle JC. Effects of heroin self-administration on cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology. 1980;67:45–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00427594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer K, Trinidad DR, Al-Delaimy WK, Pierce JP. Smoking cessation rates in the United States: A comparison of young adult and older smokers. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(2):317–322. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.112060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney ME, Poling J, Gonzalez G, Gonsai K, Kosten T, Sofuoglu M. Preliminary study of buprenorphine and bupropion for opioid-dependent smokers. The American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17:287–292. doi: 10.1080/10550490802138814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutschler NH, Stephen BJ, Teoh SK, Mendelson JH, Mello NK. An inpatient study of the effects of buprenorphine on cigarette smoking in men concurrently dependence on cocaine and opioids. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2002;4(2):223–228. doi: 10.1080/14622200210124012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahvi S, Richter K, Li X, Modali L, Arnsten J. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting in methadone maintenance patients. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(11):2127–2134. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen Y, Alford DP, Horton NJ, Saitz R. Addressing smoking cessation in methadone programs. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2005;24(2):33–48. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. A comprehensive guide for the application of contingency management procedures in standard clinic settings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ, Delucchi K, Hall SM. A meta-analysis of smoking cessation interventions with individuals in substance abuse treatment or recovery. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):1144–1156. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiff BR, Faix C, Turturici M, Dallery J. Breath carbon monoxide output is affected by speed of emptying the lungs: Implications for laboratory and smoking cessation research. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12(8):834–838. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MS, Fallon B, Sonne S, Flammino F, Nunes EV, Jiang H, et al. Smoking cessation treatment in community-based substance-abuse rehabilitation programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35(1):68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP. Good and bad times for treating cigarette smoking in drug treatment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;38(3):311–315. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2006.10399857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Choi WS, Alford DP. Smoking policies in U.S. outpatient drug treatment facilities. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2005;7(3):475–480. doi: 10.1080/14622200500144956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Choi WS, McCool RM, Harris KJ, Ahluwalia JS. Smoking cessation services in U.S. methadone maintenance facilities. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55(11):1258–1264. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Gibson CA, Ahluwalia JS, Schmelzle KH. Tobacco use and quit attempts among methadone maintenance clients. America Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(2):296–299. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Hamilton AK, Hall S, Cately D, Cox LS, Grobe J. Patterns of smoking and methadone dose in drug treatment patients. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15(2):144–153. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, McCool RM, Catley D, Hall M, Ahluwalia JS. Dual pharmacotherapy and motivational interviewing for tobacco dependence among drug treatment patients. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2005;24(4):79–90. doi: 10.1300/j069v24n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, McCool RM, Okuyemi KS, Mayo MS, Ahluwalia JS. Patients' views on smoking cessation and tobacco harm reduction during drug treatment. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2002;4(Supplement 2):S175–S182. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000032735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST, Tidey JW. Cocaine use can increase cigarette smoking: Evidence from laboratory and naturalistic settings. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1997;5:263–268. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Grabowski J, Rhoades H. The effects of high and low doses of methadone on cigarette smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;34:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Rhoades H, Grabowski J. Contingent reinforcement for reduced carbon monoxide levels in methadone maintenance patients. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20(2):171–179. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sees KL, Clark HW. When to begin smoking cessation in substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10(2):189–195. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Johnston JA, Khayrallah M, Elash CA, Gwaltney CJ, Paty JA, et al. The effect of bupropion on nicotine craving and withdrawal. Psychopharmacology. 2000;148:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s002130050022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Jarvik ME, Ling W, Rawson RA. Contingency management for tobacco smoking in methadone-maintained opiate addicts. Addictive Behavior. 1996;21(3):409–412. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Rotheram-Fuller E, Yang X, Frosch D, Nahom D, Jarvik ME, et al. Smoking cessation in methadone maintenance. Addiction. 2002;97(10):1317–1328. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC, Lamb RJ, Dallery J. Chapter 6: Tobacco. In: Higgins, Silverman, Heil, editors. Contingency Management in Substance Abuse Treatment. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: Effects of reinforcement magnitude. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:128–138. doi: 10.1007/s002130051098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton JA, Keaney F, Sutherland G. Illicit drug use as a predictor of smoking cessation treatment outcome. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;11(6):685–689. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Anderson BJ, Niaura R. Nicotine replacement therapy: Patterns of use after a quit attempt among methadone-maintained smokers. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(7):753–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Weinstock MC, Herman DS, Anderson BJ, Antholy JL, Niaura R. A smoking cessation intervention for the methadone-maintained. Addiction. 2006;101(4):599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. Contingent reinforcement for carbon monoxide reduction: within-subjects effects of pay amounts. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1984;17:477–483. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1984.17-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story J, Stark MJ. Treating cigarette smoking in methadone maintenance clients. Psychoactive Drugs. 1991;23:203–215. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1991.10472237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2002;4(2):149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No SMA 10-4856 Findings) Rockville, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2008: Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities (DASIS Series: S-49, DHHS Publication No (SMA) 09-4451) Rockville, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- West R, Baker CL, Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG. Effect of varenicline and bupropion SR on craving, nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and rewarding effects of smoking during a quit attempt. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197(3):371–377. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkin PL, Jones L, Lancaster T, Fowler GH. Which smokers are helped to give up smoking using transdermal nicotine patches? Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. British Journal of General Practice. 1996;46(404):145–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]