Abstract

Migrations to the new world brought together individuals from at least three continents. These indigenous and migrant populations inter-mated and subsequently formed new admixed populations, such as African and Latino Americans. These unprecedented events brought together genomes that had evolved independently on different continents for tens of thousands of years and presented new environmental challenges for the indigenous and migrant populations, as well as their offspring. These circumstances provided novel opportunities for natural selection to occur that could be reflected in deviations from the genome-wide ancestry distribution at specific selected loci. Here we present an analysis examining European, Native American and African ancestry based on 284 microsatellite markers in a study of Mexican Americans from the Family Blood Pressure Program. We identified two genomic regions where there was a significant decrement in African ancestry (at 2p25.1, p < 10−8 and 9p24.1, p< 2×10−5) and one region with a significant increase in European ancestry (at 1p33, p< 2 × 10−5). We show that these regions are not related to blood pressure. These locations may harbor genes that have been subjected to natural selection in the ancestral mixing of Mexicans.

Introduction

New world admixed populations provide unique opportunities for genetic admixture mapping studies (Chakraborty and Weiss 1986, Chakraborty and Weiss 1988, Hoggart et al. 2004, McKeigue 1998, Patterson et al. 2004, Risch 1992, Smith et al. 2001, Smith et al. 2004, Stephens et al. 1994, Zhu et al. 2004, 2006). Although admixture mapping, which focuses on the genome-wide distribution of ancestry, has primarily been applied to map disease genes (Collins-Schramm et al. 2002, Fernandez et al. 2003, Reich et al. 2005, Reich et al. 2007, Shriver et al. 2003, Zhu et al. 2005); similar principles can be applied to questions of population history and natural selection (Long 1991, Reed 1969, Tang et al. 2006). The recent history of Latin America, starting five centuries ago with the arrival of Christopher Columbus, has been one of large scale and widespread exchange between African, Native American and European genomes. The various Latino populations of the United States represent admixtures of European, African and Native American ancestral genomes in different proportions with considerable spatial variation depending primarily on their country of origin (Hanis et al. 1991).

While almost all molecular DNA sequence variations are selectively neutral or “near neutral”, and although the processes of mutation and random genetic drift are sufficient to maintain variation within species; the neutral theory does not deny the possibility of natural selection in determining the course of adaptive evolution at specific loci. Populations separated by continental distances, whose genetic makeup was shaped through thousands of generations in distinct environments, were suddenly exposed to an entirely new world and unfamiliar environment. This introduction to a drastically different environment, composed of distinct pathogens as well as diverse cultural and social influences, may have provided opportunities for the admixed genomes to rapidly adapt and adjust to.

In a previous report(Tang et al. 2006), we described the three distributions of individual ancestry (African, European, Native American) estimated from the combined information of 284 microsatellite loci in a sample of self-identified Hispanic (Mexican-American) subjects chosen from the multi-ethnic Family Blood Pressure Program (FBPP)(FBPP Investigators 2002, Rosenberg et al. 2002). In the current study, we estimated the African, European and Native American individual ancestry proportions at each of the 284 marker loci in 393 unrelated subjects from this same population. This sample provides a unique opportunity to examine whether natural selection may have operated on specific regions of the genome in the history of this population.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The FBPP is a collaborative effort of four research networks (GenNet, GENOA, HyperGEN, and SAPPHIRe) that aims to investigate high blood pressure and related conditions in multiple racial/ethnic groups (FBPP Investigators 2002). In total, DNA samples from 10,527 participants were genotyped at 326 autosomal genome screen microsatellite markers by the NHLBI-sponsored Mammalian Genotyping Service (Marshfield, WI) (screening set 8) and had sufficient marker data for analysis (i.e., at most 40 missing genotypes).

All individuals included in this study were Hispanics (Mexican-Americans) from the GENOA network, recruited from the Starr County, Texas field center (Daniels et al. 2004). Race/ethnicity information was obtained by self-description.

The FBPP began as a linkage-based study, and as such individuals were typically recruited as members of nuclear families. The Starr County sample included 393 families from which we randomly selected one individual per family. Although this was a study of hypertension, the subjects from the Starr County field center were not recruited based on the presence of hypertension; hence the included subjects should represent a random sample in this regard.

Data Analysis

For the admixture analysis of the 392 Mexican-Americans, we assumed a three-ancestral populations model. Because this analysis requires the addition of surrogates for the ancestral population, we also included 1378 unrelated non-Hispanic white participants from the FBPP as well as 127 African and 50 Native American individuals from the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP)(Rosenberg et al. 2002). For the latter two sets of individuals genotypes at more than three hundred STRs were available, and we included the genotypes of 284 markers which overlapped with the markers genotyped in the FBPP individuals.

We used the computer program STRUCTURE (Falush, Stephens & Pritchard 2003, Pritchard, Stephens & Donnelly 2000) to estimate the genome-wide, as well as the locus-specific ancestries in the Mexican-American subjects. The linkage model was used, with genetic distances between markers specified according to the Marshfield linkage map. In each analysis, the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm was run for 100,000 steps of burn-in, followed by another 100,000 steps.

We computed the “Δ ancestry”, deficiency or excess, at each locus using the estimated genome-wide individual ancestry (IA) as baseline. Specifically the Δ ancestry for ancestral population k at marker m is defined as

where is the locus-specific ancestry of individual i at marker m, estimated from STRUCTURE; is the overall IA of individual i, is the mean ancestry at marker m averaged over all individuals and q̄k is the proportion from ancestral population k, averaged over all individuals and the entire genome.

For the purpose of assessing statistical significance, we calculated Z scores by taking and dividing by its empirical standard deviation, derived from the distribution of values among the i individuals.

Statistical Significance

In assessing the locus to locus variation in ancestry, it is important to consider not only the statistical error of ancestry estimation, but the fact that genetic drift occurring over the generations since the original hybrid population was formed will also cause variation between loci(Long 1991, Tang et al. 2006).

To evaluate the impact of drift, one can conceptualize the ancestral origin as a defining characteristic of an allele at a specific locus. The proportion of ancestry from a given population is then equivalent to the frequency of the allele identified with that population. For example, for a di-hybrid population with African and European ancestry, if we denote African derived alleles as A and European derived alleles by E, then the proportion of African ancestry at that locus in the hybrid population is equivalent to the frequency of allele A.

We can therefore look at the admixture proportion at different independent loci in the genome as analogous to realizations from the probability distribution function of the allele frequency under random genetic drift. Therefore, we modeled admixture in our study directly using Kimura’s solution of a process of random genetic drift with a continuous model (Crow, Kimura 1970, Kimura 1955)

For the purpose of tractability, we assumed a di-hybrid rather than tri-hybrid model for this population. The justification of using a di-hybrid model in this case is the very modest locus-wise African ancestry (overall ~4%) and its lack of correlation with the European and Native American ancestries (correlation = 0.02). Conversely, as expected, the European and the Native American ancestries are almost perfectly negatively correlated (correlation = −0.973). So while studying the European (or Native American) admixture proportions we can reasonably neglect the African ancestry, and when we study the African Ancestry we can hypothetically combine the European and Native Americans as one population. In this case, the introduction of a tri-hybrid model unnecessarily complicates the computations without any difference in inference (data not shown).

Kimura has formally shown that the probability distribution of the allele frequency pt, after t generations, depends upon the initial allele frequency, the effective population size and the number of generations through a complex function. He also derived exact expressions of moments of the distribution(Kimura 1955). If we assume that we start from a population with allele frequency p (in our case corresponding to an initial admixture proportion of p), and if we denote μk(t) as the kth order raw moment of the allele frequency distribution after t generations, then we have:

It is easily shown from the above equations that the distribution of pt is positively (negatively) skewed if p is less (greater) than ½. This again is intuitive as there is more room on the positive (right hand) side of the distribution from which to draw realizations of pt when p is less that 0.5, and vice versa. It is also apparent that both the variance and skewness increase as the number of generations increases, depending on population size. For realistic number of generations t and population size and ancestral proportion p, we used these distributions to determine the likelihood of extreme points in our observed distributions.

We also used a combination of resampling methods(Efron, Tibshirani 1993) to eliminate any possible bias that might have risen due to inadequate sample size. To check the validity of our findings we generated a bootstrap sample (by resampling individuals with replacement) of size 392 only at the significant sites. For each of these samples we computed the mean African ancestry (at sites GGAA20G10 and GATA62F03), European ancestry (at sites GATA72H07 and GATA129H04) and repeat the process 10000 times. Comparing our estimate with the bootstrap mean, and studying the higher order moments of the bootstrap distribution we conclude that there is no systematic error (Supplementary Table 1), and none of the findings is an outlier affected by small sample size.

We then did a more rigorous test, where we again generated bootstrap samples of size 392 by resampling individuals. For each bootstrap sample after leaving out putative marker sites GGAA20G10 and GATA62F03, we computed the African ancestry for the remaining 282 sites. We did a similar analysis for European ancestry, this time leaving out the putative sites GATA72H07 and GATA129H04. This process was repeated 2000 times. So our null distributions pertaining to both African and European ancestry had 564000 observations. We then compared our observed African and European ancestry at the sites of interest to assess significance.

Results

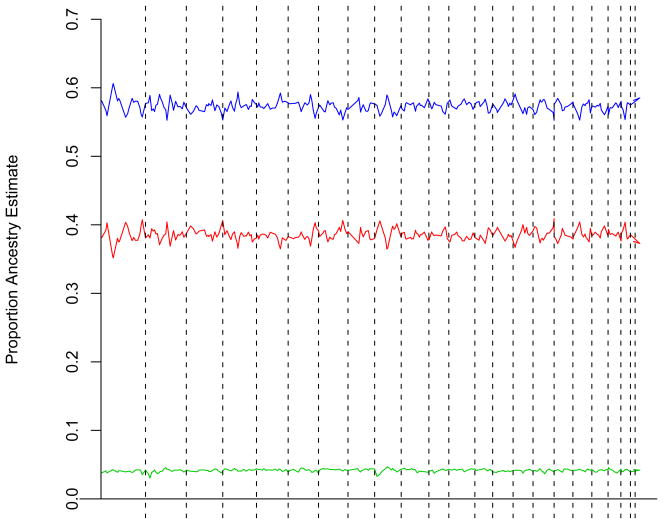

Figure 1 provides the estimated African, European and Native American ancestry at each marker locus around the genome for the total sample of 393 Mexican Americans. As can be seen, the African ancestry is generally low, with a mean of .042, and also very modest variance among loci. On the other hand, European ancestry and Native American ancestry are much greater on average (means of .57 and .39, respectively) and with much greater variance. Careful examination of this figure also suggests a few potential outlier points, specifically decreases on chromosomes 2 and 9 for African ancestry, and increased European ancestry on chromosome 1.

Figure 1.

Genome-wide distribution of African (green line), European (blue line) and Native American (red line) ancestry.

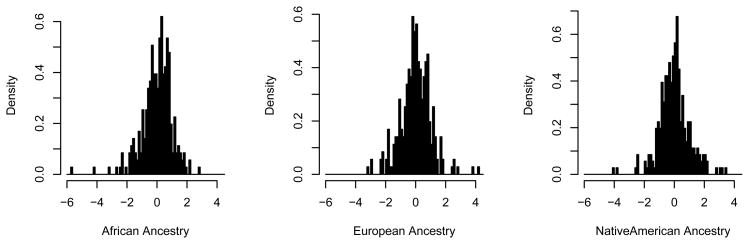

To address the question of outlier points more directly, we plotted the distribution of Z scores for each of the three ancestries (Figure 2). This figure confirms our initial impression regarding the existence of outlier points. The most extreme point in the distribution for African ancestry is approximately 6 standard deviations below the mean; this point corresponds to a location on chromosome 2p25, The second most extreme point in this distribution is about 4.5 standard deviations below the mean, and corresponds to a location on chromosome 9p24. Studying the Z score distribution for European ancestry, the most extreme point is approximately 4.5 standard deviations above the mean, and corresponds to a locus on chromosome 1p33.

Figure 2.

Distributions of Z-scores for African, European and Native American ancestry.

Because the mean of African ancestry for these data was 0.042, the expected distribution of locus-specific Delta-ancestry, and therefore locus-specific Z-scores, is right-skewed (see Methods). However, our two most extreme outliers in this distribution were on the left side of the distribution, that is regions with relative deficiencies of African ancestry. Therefore, the most extreme points, with close to 6 and 4.5 standard deviations difference from the mean are unlikely to be due simply to chance.

The mean value for European ancestry for these data was 0.57, which is not very different from 0.5, implying that the genome-wide distribution for European (and Native American) ancestry should be reasonably symmetric, or slightly negatively (positively) skewed. As was true for the African ancestry, here too we find two extreme outlying points at the end of the distribution with the predicted shorter tail. These two loci are adjacent points on chromosome 1p33, the most extreme of which is close to 4.5 standard deviations from the mean.

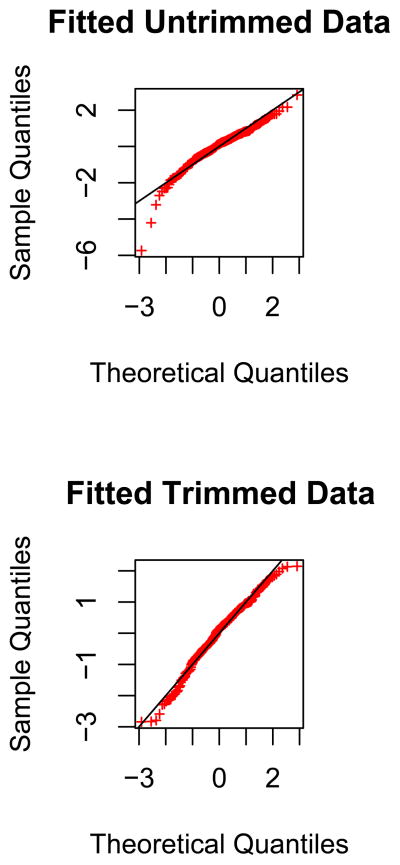

We then tried to fit a ‘null’ distribution to the to assess the significance of our findings. A normal distribution did not fit the data well (by a Shapiro-Wilks Test; p-value<10−8). However, when we trimmed the data by excluding the two most extreme points on either end of the distribution, a normal distribution now gave an acceptable fit (Shapiro-Wilks Test; p-value>.10). The poor and improved fit of a normal distribution to the original and trimmed data are given in the Q-Q plots in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Q-Q plot of Z-scores for African ancestry for untrimmed and trimmed data.

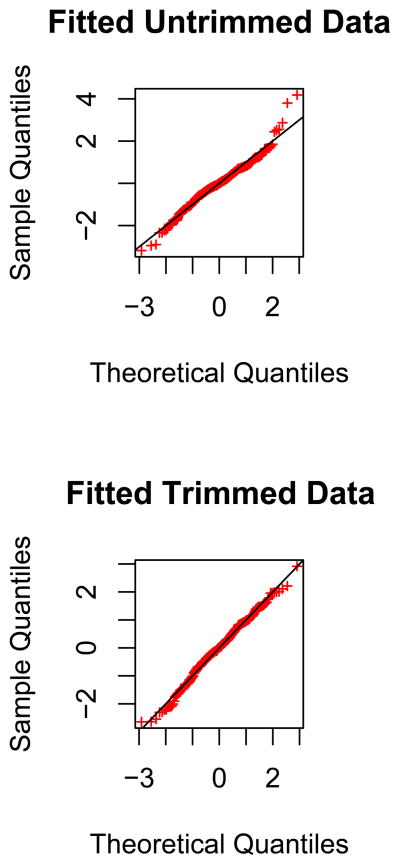

We similarly attempted to fit a normal distribution to the values of ( ). As before, a normal distribution did not fit the data well (Shapiro-Wilks Test; p-value<10−4). When we trimmed the data by excluding the two most extreme points on either end of the distribution, we obtained a good fit to a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilks Test; p-value >.10). Again, this can be seen by the Q-Q distributions, which show a poor fit in the original distribution but a good fit in the trimmed distribution (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Q-Q plot of Z-scores for European ancestry for untrimmed and trimmed data.

The removal of the outliers on either side affects the second and fourth order moments of the distribution of q̃m. Thus the trimmed distributions have reduced mass in the tails and are also more kurtotic. The significance of our findings obtained by applying p-values from Z-scores using the untrimmed distribution will therefore be the most conservative, followed by the trimmed distribution, which itself is conservative because we are fitting a symmetric distribution instead of the expected skewed distribution (where the expected skewness is in the direction opposite to the outlier points). In Table 1 we present the significance of the regions which show reduced African ancestry and increased European ancestry, after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. We computed the p-values using the more conservative non-trimmed normal distribution and also the trimmed normal distribution.

Table 1.

Extreme outlier points showing decreased African and increased European ancestry.

| African Ancestry:

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHROM | Marker Names | DNAME | DISTANCE (in cM) | African Ancestry | Untrimmed Normal (p-value) | Trimmed (p-value) |

| 2 | GGAA20G10 | D2S1400 | 27.6 | 0.028966 | 4.78E-09** | 4.81E-13** |

| 9 | GATA62F03 | D9S2169 | 14.23 | 0.032371 | 1.28E-05** | 7.87E-08** |

| European Ancestry:

| ||||||

| CHROM | Marker Names | DNAME | DISTANCE (in cM) | European Ancestry | Untrimmed Normal (p-value) | Trimmed (p-value) |

| 1 | GATA129H04 | D1S3721 | 72.59 | 0.6087225 | 7.18068E-05* | 2.78E-06** |

| 1 | GATA72H07 | D1S2134 | 75.66 | 0.6122591 | 1.44363E-05** | 2.93E-07** |

: Significant at 5% after Bonferroni correction

: Significant at 1% after Bonferroni correction

We also used a combination of resampling methods(see methods section) to eliminate any possible bias that might have risen due to inadequate sample size. To check the validity of our findings we generated 10000 bootstrap samples (by resampling individuals with replacement) of size 392 only at the significant sites. For each of these samples we computed the mean African ancestry at sites GGAA20G10 and GATA62F03 and European ancestry at sites GATA72H07 and GATA129H04. Comparing our observed ancestries in the original sample with the bootstrap mean we do not find evidence of any systematic bias in the samples. Studying the higher order moments of the bootstrap distribution we conclude that there is no systematic error due to small sample size.

We again generated 2000 bootstrap samples of size 392 by resampling individuals. For each bootstrap sample after leaving out putative marker sites GGAA20G10 and GATA62F03, we computed the African ancestry for the remaining 282 sites. We did a similar analysis for European ancestry, this time leaving out the putative sites GATA72H07 and GATA129H04. So our null distributions pertaining to both African and European ancestry had 564000 observations. The moments of the bootstrap distribution are tabulated in supplementary table 2. We then compared our observed African and European ancestry at the sites of interest to assess significance. We observe African ancestry values less the ancestry at GGAA20G10 only 523 times (~0.09% of the sample) and less than GATA62F03 only 3525 times (~0.6 % of the sample). When we repeat the similar experiment and calculated the European ancestry 564000 times, we observe European ancestry in excess of the ancestry at GATA129H04 only 1862 times (~0.3% of the sample) and European ancestry in excess of the ancestry at GATA72H07 only 949 times (~0.16 % of the sample). Hence we concluded that our results are unlikely to be biased by inadequate sample size.

To assess whether our results might be a result of genotyping problems with the significant markers, we examined those markers for amount of missing data as well as Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the underlying ancestral populations. All markers were found to be in HWE and missing fewer than 5% of genotypes.

Discussion

Admixture in the present day Mexican American population has occurred over the past 500 years, during the post-Columbian era of the New World. As noted before (FBPP Investigators 2002), this Latino population is composed primarily of European and Native American ancestry, with a modest amount of African ancestry. In fact, the history of Starr County Texas, where the study subjects reside, documents the presence of descendents of African slaves; the 1880 census documents 211 blacks out of a total population of 8304 [reference: Handbook of Texas Online, url: http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/SS/hcs13.html] Thus, the larger variance in the distribution of European and Native American ancestry is likely attributable to their initial higher proportion in the creation of the admixed population than to any large difference in the timing of admixture.

Our evidence for loci likely to have undergone historical selection in this population derives from outlier analysis. We noted that a normal distribution actually fit the observed Z-score distributions quite well, both for African and European ancestry, except for a few extreme outliers. In both cases, when we removed the two most extreme observations from either tail, a good fit to a normal distribution was obtained. The fact that the most extreme observations occurred in the tail predicted to have less skewness increases the likelihood that these regions had undergone historical selection. We also did extensive bootstrap sampling to eliminate possibility of inadequate sample size influencing the inferences.

The microsatellite marker map we used was not extremely dense. Hence, the three regions that we identified, on chromosome 2p25 and 9p24 (decreased African Ancestry) and 1p33 (excess European ancestry), are broad and could contain numerous potential targets of selection. It is possible that further analysis using SNP markers as well as a larger number of subjects could narrow these regions further.

We also sought to determine whether our results were in any way influenced by hypertension or diabetes, two of the most common disease outcomes in this population. For the three genomic locations we identified, the local ancestry was no different for hypertensives and normotensives, nor for the diabetics and non-diabetics.

Our results are different from those presented by Tang et al(Tang et al. 2007) in a study of ancestral admixture in Puerto Ricans. Those authors found evidence for excess African ancestry on chromosome 6p and excess Native American ancestry on chromosomes 8q and 11q. Despite both being Latino populations, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans are actually quite distinct regarding their genetic as well a social and demographic histories. On average, Mexicans are primarily European and Native American in ancestry, with a modest African contribution(Tang et al. 2006) by contrast, Puerto Ricans have substantial African ancestry and more modest Native American ancestry(Tang et al. 2007). It is intriguing to consider the possibility that different environmental exposures operated on these populations with distinct genetic admixtures to produce differing patterns of selection. It would be particularly enlightening to study additional Latino populations, with different ancestral proportions, to determine the degree of overlap that may exist with the results obtained for these two populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

“The following investigators are associated with the Family Blood Pressure Program:

GenNet Network: Alan B. Weder (Network Director), Lillian Gleiberman (Network Coordinator), Anne E. Kwitek, Aravinda Chakravarti, Richard S. Cooper, Carolina Delgado, Howard J. Jacob, and Nicholas J. Schork

GENOA Network: Eric Boerwinkle (Network Director), Tom Mosley, Alanna Morrison, Kathy Klos, Craig Hanis, Sharon Kardia, and Stephen Turner

HyperGEN Network: Steven C. Hunt (Network Director), Janet Hood, Donna Arnett, John H. Eckfeldt, R. Curtis Ellison, Chi Gu, Gerardo Heiss, Paul Hopkins, Aldi T. Kraja, Jean-Marc Lalouel, Mark Leppert, Albert Oberman, Michael A. Province, D.C. Rao, Treva Rice, and Robert Weiss

SAPPHIRe Network: David Curb (Network Director), David Cox, Timothy Donlon, Victor Dzau, John Grove, Kamal Masaki, Richard Myers, Richard Olshen, Richard Pratt, Tom Quertermous, Neil Risch and Beatriz Rodriguez

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Dina Paltoo and Cashell E. Jaquish

Web Site: http://www.biostat.wustl.edu/fbpp/FBPP.shtml

This work was supported by grants awarded to the Family Blood Pressure Program, which is supported by a series of cooperative agreements from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute to GenNet, HyperGEN, GENOA and SAPPHIRe.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests

References

- Chakraborty R, Weiss KM. Admixture as a tool for finding linked genes and detecting that difference from allelic association between loci. PNAS. 1988;85:9119–9123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty R, Weiss KM. Frequencies of complex diseases in hybrid populations. Am J Phys Anthrop. 1986;70:489–503. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330700408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins-Schramm HE, Phillips CM, Operario DJ, Lee JS, Weber JL, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Cooper R, Li H, Seldin MF. Ethnic-difference markers for use in mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:737–750. doi: 10.1086/339368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow JF, Kimura M. An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory, Harper, Row. 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels PR, Kardia SL, Hanis CL, Brown CA, Hutchinson R, Boerwinkle E, Turner ST Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy study . Familial aggregation of hypertension treatment and control in the Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy (GENOA) study. Am J Med. 2004;116:676–681. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164:1567–1587. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FBPP Investigators. Multi-center genetic study of hypertension: The Family Blood Pressure Program (FBPP) Hypertension. 2002;39:3–9. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.100415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez JR, Shriver MD, Beasley TM, Rafla-Demetrious N, Parra E, Albu J, Nicklas B, Ryan AS, McKeigue PM, Hoggart CL, Weinsier RL, Allison DB. Association of African genetic admixture with resting metabolic rate and obesity among women. Obes Res. 2003;11:904–911. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanis CL, Hewett-Emmett D, Bertin TK, Schull WJ. Origins of US Hispanics Implications for diabetes. Diab care. 1991:618–627. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.7.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggart CJ, Shriver MD, Kittles RA, Clayton DG, McKeigue PM. Design and analysis of admixture mapping studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:965–978. doi: 10.1086/420855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. Solution of a Process of Random Genetic Drift with a Continuous Model. PNAS. 1955;41:144–150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.41.3.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JC. The genetic structure of admixed populations. Genetics. 1991;127:417–428. doi: 10.1093/genetics/127.2.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeigue PM. Mapping genes that underlie ethnic differences in disease risk: methods for detecting linkage in admixed populations, by conditioning on parental admixture. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:241–251. doi: 10.1086/301908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson N, Hattangadi N, Lane B, Lohmueller KE, Hafler DA, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL, Smith MW, O’Brien SJ, Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Reich D. Methods for high-density admixture mapping of disease genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:979–1000. doi: 10.1086/420871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed TE. Caucasian genes in American Negroes. Science. 1969;165:762–768. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3895.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich D, Patterson N, De Jager PL, McDonald GJ, Waliszewska A, Tandon A, Lincoln RR, DeLoa C, Fruhan SA, Cabre P, Bera O, Semana G, Kelly MA, Francis DA, Ardlie K, Khan O, Cree BA, Hauser SL, Oksenberg JR, Hafler DA. A whole-genome admixture scan finds a candidate locus for multiple sclerosis susceptibility. Nat genet. 2005;37:1113–1118. doi: 10.1038/ng1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich D, Patterson N, Ramesh V, De Jager PL, McDonald GJ, Tandon A, Choy E, Hu D, Tamraz B, Pawlikowska L, Wassel-Fyr C, Huntsman S, Waliszewska A, Rossin E, Li R, Garcia M, Reiner A, Ferrell R, Cummings S, Kwok PY, Harris T, Zmuda JM, Ziv E Health, Aging and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. Admixture mapping of an allele affecting interleukin 6 soluble receptor and interleukin 6 levels. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:716–726. doi: 10.1086/513206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N. Mapping Genes for complex diseases using association studies in admixed populations. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:13. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg NA, Pritchard JK, Weber JL, Cann HM, Kidd KK, Zhivotovsky LA, Feldman MW. Genetic structure of human populations. Science. 2002;298:2381–2385. doi: 10.1126/science.1078311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriver MD, Parra EJ, Dios S, Bonilla C, Norton H, Jovel C, Pfaff C, Jones C, Massac A, Cameron N, Baron A, Jackson T, Argyropoulos G, Jin L, Hoggart CJ, McKeigue PM, Kittles RA. Skin pigmentation, biogeographical ancestry and admixture mapping. Hum genet. 2003;112:387–399. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0896-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MW, Lautenberger JA, Shin HD, Chretien JP, Shrestha S, Gilbert DA, O’Brien SJ. Markers for mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium in African American and Hispanic populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1080–1094. doi: 10.1086/323922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MW, Patterson N, Lautenberger JA, Truelove AL, McDonald GJ, Waliszewska A, Kessing BD, Malasky MJ, Scafe C, Le E, De Jager PL, Mignault AA, Yi Z, De The G, Essex M, Sankale JL, Moore JH, Poku K, Phair JP, Goedert JJ, Vlahov D, Williams SM, Tishkoff SA, Winkler CA, De La Vega FM, Woodage T, Sninsky JJ, Hafler DA, Altshuler D, Gilbert DA, O’Brien SJ, Reich D. A high-density admixture map for disease gene discovery in african americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1001–1013. doi: 10.1086/420856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens JC, Briscoe D, O’Brien SJ. Mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium in human populations: limits and guidelines. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:809–824. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Choudhry S, Mei R, Morgan M, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Burchard EG, Risch NJ. Recent genetic selection in the ancestral admixture of Puerto Ricans. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:626–633. doi: 10.1086/520769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Jorgenson E, Gadde M, Kardia SL, Rao DC, Zhu X, Schork NJ, Hanis CL, Risch N. Racial admixture and its impact on BMI and blood pressure in African and Mexican Americans. Hum genet. 2006;119:624–633. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Luke A, Cooper RS, Quertermous T, Hanis C, Mosley T, Gu CC, Tang H, Rao DC, Risch N, Weder A. Admixture mapping for hypertension loci with genome-scan markers. Nat genet. 2005;37:177–181. doi: 10.1038/ng1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Cooper RS, Elston RC. Linkage analysis of a complex disease through use of admixed populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1136–53. doi: 10.1086/421329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Zhang S, Tang H, Cooper R. A classical likelihood based approach for admixture mapping using EM algorithm. Hum Genet. 2006;120:431–45. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0224-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.