Abstract

Sixty-one phenyl 4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonates (PIB-SOs) and 13 of their tetrahydro-2-oxopyrimidin-1(2H)-yl analogues (PPB-SOs) were prepared and biologically evaluated. The antiproliferative activities of PIB-SOs on 16 cancer cell lines are in the nanomolar range and unaffected in cancer cells resistant to colchicine, paclitaxel, and vinblastine or overexpressing the P-glycoprotein. None of the PPB-SOs exhibit significant antiproliferative activity. PIB-SOs block the cell cycle progression in the G2/M phase and bind to the colchicine-binding site on β-tubulin leading to cytoskeleton disruption and cell death. Chick chorioallantoic membrane tumor assays show that compounds 36, 44, and 45 efficiently block angiogenesis and tumor growth at least at similar levels as combretastatin A-4 (CA-4) and exhibit low to very low toxicity on the chick embryos. PIB-SOs were subjected to CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses to establish quantitative structure–activity relationships.

Introduction

Microtubules are key components of the cytoskeleton and are involved in a wide range of cellular functions, notably cell division where they are responsible for mitotic spindle formation and proper chromosomal separation.(1) Consequently, microtubules have been for the past decades important targets for the design and the development of several potent natural and synthetic anticancer drugs(2) such as paclitaxel,(3) epothilone A,(4) vinblastine,(5) and combretastatin A-4(6) (1, CA-4), molecules that are of utmost importance in the management of cancers such as ovarian, breast, and prostate cancers.7,8 However, the efficacy and the clinical usefulness of currently available antimicrotubules is impeded by the occurrence of chemoresistane, systemic toxicity, and poor biopharmaceutical properties.9,10 Therefore, the search for new antimicrotubule agents exhibiting improved biopharmaceutical profiles and pharmacodynamics is the focus of numerous academic and industrial teams.(11)

In the past decades, ligands to the colchicine-binding site (C-BS) were extensively studied and many interesting compounds were identified and tested. To that end, CA-4 isolated from the bark of Combretum caffrum(12) was shown to exhibit potent antiangiogenic and antitumoral activies. However, poor solubility of the drug impinged its clinical development and required the preparation of more soluble derivatives such as CA-4 phosphate sodium salt(13) (2) and the amino acid hydrochloride salt(14) (3). These molecules represent promising drugs in various clinical settings, showing potent activities to disrupt vasculature and to reduce significantly the tumoral blood flow.(15) Unfortunately, CA-4, 2, and 3 exhibit many deleterious effects such as hypertension, hypotension, tachycardia, tumor pain, and lymphopenia.(16) In addition, the activity of CA-4, 2, and 3 is hampered by a short biological half-life17,18 and isomerization of their active cis-stilbene conformation into the corresponding inactive trans analogues.13,19 To overcome the problem, the ethenyl bridge of the stilbene moiety was converted into more biologically stable molecules utilizing polar groups such as carbonyl (e.g., phenstatin),(20) arylthioindole,(21) oxazole, triazole, and thiophene bioisosteres.(22) In that context, Gweltaney et al. have successfully converted the ethenyl group of CA-4 into the more stable and more polar sulfonate group(23) (4).

N-Phenyl-N′-(2-chloroethyl)urea (CEU) is another class of antimicrotubule agent characterized by its unique ability to acylate Glu198 of β-tubulin, an amino acid located in a pocket adjacent to the C-BS. The acylation of Glu198 leads to microtubule depolymerization, hypoacetylation of Lys40 on α-tubulin, cytoskeleton disruption, and anoikis.24,25 CEU analogues such as 1-(2-chloroethyl)-3-(4-iodophenyl)urea (5)26−28 or 1-(2-chloroethyl)-3-(3-(5-hydroxypentyl)phenyl)urea (6)29−31 inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth in three distinct animal models.(25) The biodistribution of CEU analogues to organs of the gastrointestinal tract suggests that they might be promising new drugs for the treatment of colorectal cancers.32,33 Several CEU subsets were also found to be devoid of antimicrotubule affinity and to bind covalently to proteins such as thioredoxin isoform 1,34−36 prohibitin 1,(37) and the mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel 1.(38)

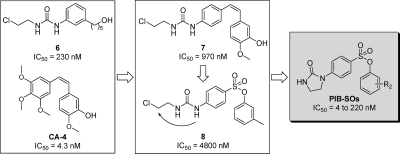

Design of Substituted Phenyl (2-Oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonates

Computational experiments conducted on antimicrotubule CEU analogues led to the hypothesis that the N-phenyl-N′-(2-chloroethyl)urea pharmacophore moiety of CEU might be a bioisosteric equivalent to the trimethoxyphenyl ring of CA-4 and several other drugs binding to the C-BS.39,40 This hypothesis was confirmed by the synthesis and biological evaluation of molecular hybrids where the trimethoxyphenyl moiety of CA-4 was replaced by the pharmacophore moiety of CEU to give compounds such as 1-(4-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxystyryl)phenyl)-3-(2-chloroethyl)urea (7).(41) Several of these molecular hybrids exhibited antiproliferative activity through the acylation of Glu198 as observed with the original CEU. Subsequently, we initiated the development of new CEU analogues incorporating the molecular scaffold of CA-4 to enhance efficacy, stability, and polarity. We prepared new molecular hybrids based on the conversion of the trimethoxyphenyl ring of compound 4 into an N-phenyl-N′-(2-chloroethyl)urea moiety to generate several CEU-sulfonate analogues (8). A number of 8 derivatives exhibited cytocidal activity at the micromolar level on several tumor cell lines and generally blocked the cell cycle progression in the G2/M phase. We previously showed that the cyclization of the 2-chloroethylurea moiety of CEU into 4,5-dihydrooxazol-2-amine derivatives improved the cytocidal activity of CEU.34,36,42 On the basis of these results, we hypothesized that the cyclization of the N-phenyl-N′-(2-chloroethyl)urea moiety of 8 might also be beneficial to the antiproliferative activity.

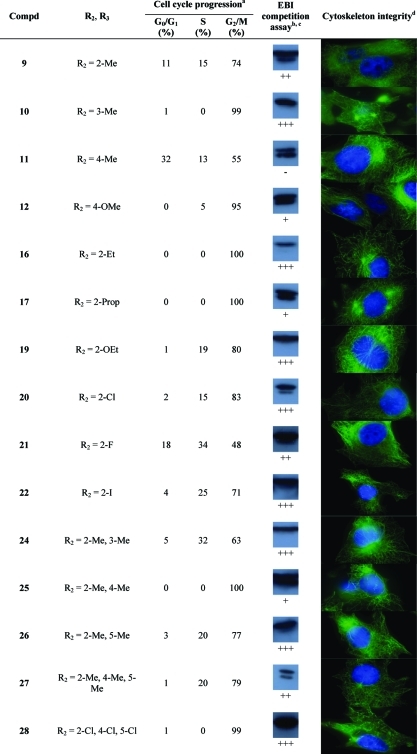

In this study, we described the preparation and the evaluation of new phenyl 4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate derivatives (PIB-SOs) as antiproliferative agents targeting the C-BS. We assessed the effect of the nature and the position of the substituents on the aromatic ring B (PIB-SOs 9–68) on the antiproliferative activity, on the binding to the C-BS, and on the antineoplastic and toxic activities on human cancer cells grafted onto the chick chorioallantoic membrane tumor (CAM) assays. Thirteen of the most potent PIB-SO derivatives were used to evaluate the effect on the aforementioned parameters of enlarging the imidazolidin-2-one ring of PIB-SO into a tetrahydropyrimidin-2(1H)-one ring (PPB-SOs 69–81) (Figure 1).

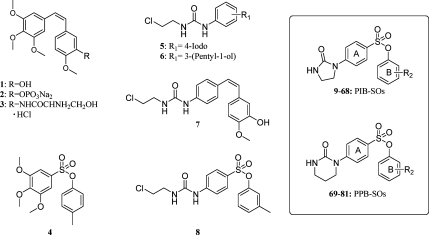

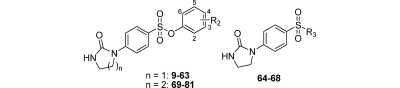

Figure 1.

Structures of CA-4 and 2–81.

Results

Chemistry

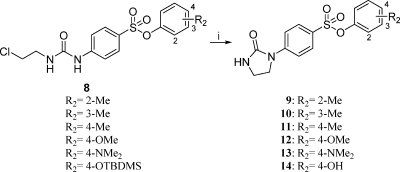

Initially, 8 derivatives were prepared as follows. 4-Nitrodiphenylsulfonates were obtained by nucleophilic addition of the appropriate phenol to 4-nitrophenylsulfonyl chloride followed by the reduction of the nitro group into its aniline. The relevant anilines were then added to 2-chloroethyl isocyanate to yield the corresponding 8 derivatives. Finally, PIB-SOs 9–14 were prepared from the catalytic cyclization of the CEU sulfonates in the presence of KF adsorbed on Al2O3 (4:6) in refluxing acetonitrile (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (i) Al2O3/KF, CH3CN.

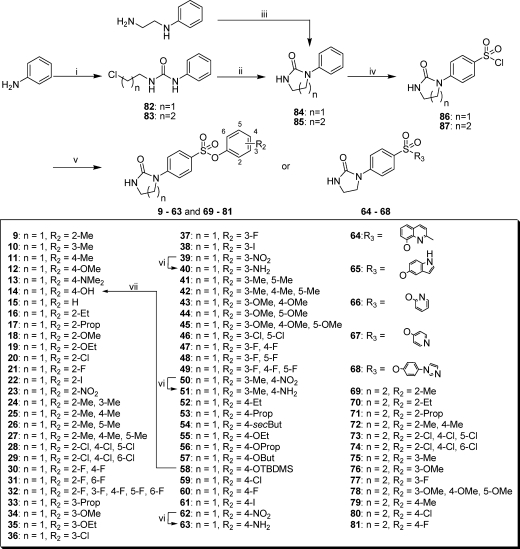

The aforementioned preparation of 8 derivatives was a long and tedious process. Therefore, we used an easier and more efficient approach for the synthesis of PIB-SOs and PPB-SOs 9–81 (Scheme 2)43,44 based on the nucleophilic addition of aniline to either 2-chloroethyl isocyanate or 3-chloropropyl isocyanate in methylene chloride at 25 °C followed by cyclization into the corresponding 1-phenylimidazolidin-2-one (84) or tetrahydro-3-phenylpyrimidin-2(1H)-one (85) using sodium hydride in THF at 25 °C. Compound 84 was also prepared using triphosgene, N-phenylethylenediamine, and triethylamine in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran at 0 °C. 4-(2-Oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzene-1-sulfonyl chloride (86) and 4-(tetrahydro-2-oxopyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)benzene-1-sulfonyl chloride (87) were obtained by chlorosulfonation of 84 and 85 by chlorosulfonic acid in carbon tetrachloride at 0 °C. Compounds 9–81 were synthesized by nucleophilic addition of an appropriate phenol on either compound 86 or 87 in the presence of triethylamine in methylene chloride at 25 °C. Aniline 40, 51, and 63 were obtained by the reduction of the nitro group on 39, 50, and 62 under hydrogen atmosphere in the presence of palladium on charcoal in ethanol. Phenol 14 was obtained by deprotection of the tert-butyldimethylsilyl intermediate 58 in the presence of tributylammonium fluoride in THF.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (i) 2-chloroethyl isocyanate or 3-chloropropyl isocyanate, DCM; (ii) NaH, THF; (iii) triphosgene, TEA, THF; (iv) ClSO3H, CCl4; (v) relevant phenol, triethylamine, DCM; (vi) H2, Pd/C 10%, EtOH; (vii) TBAF, THF.

Evaluation of the Antiproliferative Activity

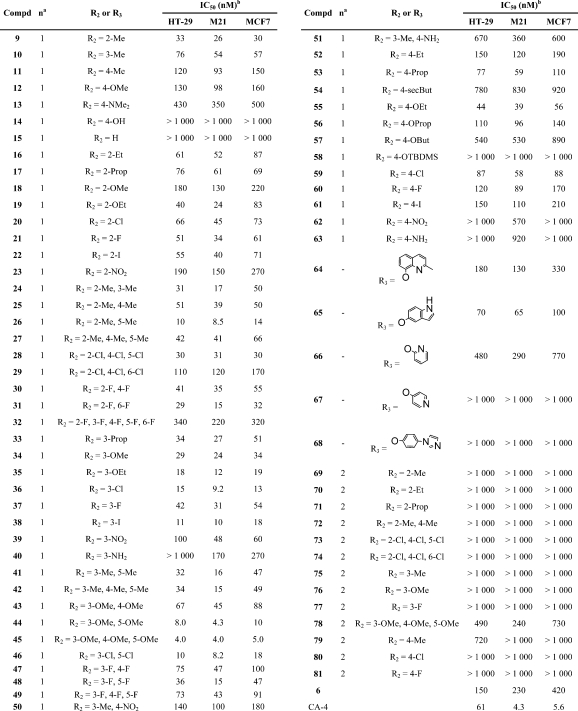

The antiproliferative activity of PIB-SO and PPB-SO derivatives was assessed on three human cancer cell lines, namely, HT-29 colon carcinoma, M21 skin melanoma, and MCF7 breast carcinoma cells. These cell lines were selected, as they are good representatives of tumor cells originating from the three embryonic germ layers. Cell growth inhibition was assessed according to the NCI/NIH Developmental Therapeutics Program.(45) The results are summarized in Table 1 and expressed as the concentration of drug inhibiting cell growth by 50% (IC50).

Table 1. Evaluation of the Antiproliferative Activity of PIB-SOs, PPB-SOs, CA-4, and Compound 6 on HT-29, M21, and MCF7 Cells.

The dash (−) indicates “not applicable”.

IC50 is expressed as the concentration of drug inhibiting cell growth by 50%.

Mechanism of Action

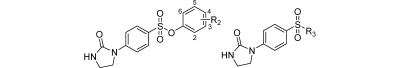

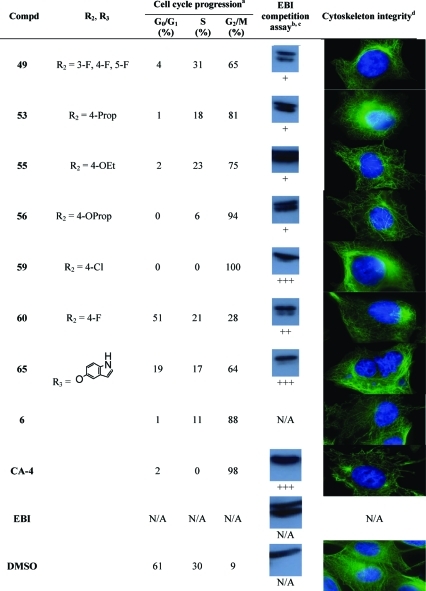

CA-4 and compounds 2–7 are known C-BS antagonists, disrupting the polymerization of tubulin heterodimers, inhibiting cell cycle progression in the G2/M phase, and leading to anoikis. Therefore, we have conducted experiments to identify the mechanism involved in the cytocidal activity of PIB-SOs in relation to their expected binding to the C-BS on β-tubulin. The evaluation was conducted using compounds 9–12, 16, 17, 19–22, 24–28, 30, 31, 33–39, 41–49, 53, 55, 56, 59, 60, and 65 that were exhibiting IC50 lower than 100 nM in M21 tumor cells. We first assessed their effects on cell cycle progression. Table 2 shows the percentage of M21 cells in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases after treatment with the selected PIB-SOs together with CA-4 and compound 6 at 5 times their respective IC50. Afterward, we assessed the binding of these compounds to the colchicine-binding site. To that end, we developed a quick and simple detection procedure based on the competition between the bisthioalkylation of Cys239 and Cys354 by N,N′-ethylene-bis(iodoacetamide) (EBI) and drugs binding to the C-BS to assess the ability of anti-C-BS agents to occupy that binding site.(46) Briefly, the β-tubulin adduct formed by the covalent binding of EBI on Cys239 and Cys354 is easily detectable by Western blot as an immunoreacting band of β-tubulin migrating faster than the native β-tubulin. The occupancy of the C-BS by relevant antimitotics inhibits the formation of the EBI/β-tubulin adduct, resulting in an assay that allows the easy and inexpensive screening of new molecules targeting the C-BS. Table 2 shows the results obtained from the competition between EBI at 100 μM and PIB-SOs 9–12, 16, 17, 19–22, 24–28, 30, 31, 33–39, 41–49, 53, 55, 56, 59, 60, and 65 at 1000 times their respective IC50 on MDA-MB-231 cells. Finally, the effect of PIB-SOs on the cytoskeleton was also visualized using a fluorescent anti-β-tubulin antibody and immunofluorescence techniques (Table 2).

Table 2. Effects of the Most Potent PIB-SOs, CA-4, and Compound 6 on Cell Cycle Progression, Cytoskeleton Integrity, and Results of a Competition Assay with EBI.

For cell cycle progression, M21 cells were incubated in presence of PIB-SOs at 5 times their respective IC50 for 24 h.

For competition assay with EBI, MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated in the presence of PIB-SOs at 1000 times their respective IC50 for 2 h and afterward in the presence of 100 μM EBI for 1.5 h.

Inhibition coding: +++, strong inhibition; ++, significant inhibition; +, weak inhibition; −, no inhibition; N/A, not applicable.

M21 cells were treated for 16 h with the drug at 5 times their respective IC50, and cellular microtubule structures were visualized using indirect immunofluorescence using an anti-β-tubulin monoclonal antibody.

Antiproliferative Activity of PIB-SOs on Chemoresistant and Wild-Type Cancer Cells

The antiproliferative activity of compounds 12, 26, 31, 35, 36, 38, 44–46, and 60 was assessed on 10 wild-type cancer and three chemoresistant cell lines (Tables 3 and 4). Wild-type cancer cell lines were Chinese hamster ovary CHO, human chronic myelogenous leukemia K562, murine lymphocytotic leukemia L1210, murine macrophages P388D1, murine melanoma B16F0, human prostate carcinoma DU 145, human fibrosarcoma HT-1080, human breast adenocarcinoma MDA-MB-231, human ovarian SKOV3, and T cell leukemia CEM cells. Chemoresistant cancer cells were paclitaxel-resistant CHO-TAX 5-6(47) colchicine- and vinblastine-resistant CHO-VV 3-2,(48) and multidrug-resistant leukemia CEM-VLB49,50 cells. Colchicine,(51) paclitaxel, and vinblastine were used as positive controls. The concentration of drug inhibiting cell growth by 50% is expressed as the IC50. Cell growth inhibition was assessed according to the NCI/NIH Developmental Therapeutics Program.(45)

Table 3. Antiproliferative Activity of Compounds 12, 26, 31, 35, 36, 38, 44–46, 60, Colchicine, Paclitaxel, and Vinblastine on CHO, K562, L1210, P388D1, B16F0, DU-145, HT-1080, MDA-MB-231, SKOV3, and CEM Cells.

| IC50 (nM)d |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | CHO | K562 | L1210 | P388D1 | B16F0 | DU 145 | HT-1080 | MDA-MB-231 | SKOV3 | CEM |

| 12 | 240 | 240 | 250 | 260 | 510 | 650 | 240 | 760 | 320 | 250 |

| 26 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 19 | 49 | 57 | 24 | 69 | 29 | 19 |

| 31 | 73 | 65 | 67 | 76 | 91 | 170 | 65 | 100 | 72 | 68 |

| 35 | 32 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 65 | 72 | 34 | 55 | 42 | 20 |

| 36 | 18 | 16 | 17 | 19 | 46 | 58 | 19 | 45 | 22 | 17 |

| 38 | 17 | 14 | 19 | 18 | 30 | 57 | 19 | 48 | 23 | 17 |

| 44 | 7.3 | 7.5 | 6.4 | 7.8 | 25 | 25 | 8.2 | 14 | 6.8 | 7.1 |

| 45 | 7.4 | 2.5 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 5.9 | 9.4 | 6.1 | 7.1 |

| 46 | 17 | 7.2 | 9.6 | 7.4 | 41 | 66 | 18 | 26 | 16 | 16 |

| 60 | 230 | 180 | 140 | 240 | 250 | 550 | 190 | 360 | 210 | 200 |

| Cola | 220 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 28 | 13 | 10 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 7.9 |

| Pacb | 170 | 0.71 | 0.40 | 35 | 28 | 1.3 | 0.15 | 9.1 | 2.6 | 0.27 |

| Vblc | 17 | 0.36 | 0.16 | 1.8 | 0.099 | 0.063 | 0.099 | 0.12 | 0.039 | 0.38 |

Col, colchicine.

Pac, paclitaxel.

Vbl, vinblastine.

IC50: concentration of drug inhibiting cell growth by 50%.

Table 4. Antiproliferative Activity of Compounds 12, 26, 31, 35, 36, 38, 44–46, 60, Colchicine, Paclitaxel, and Vinblastine on Chemoresistant TAX 5-6, CHO-VV 3-2, and CEM-VLB Cells.

| compd | IC50 (nM)d CHO-TAX 5-6e |

ratio resistant/wild-type CHO-TAX 5-6/CHO |

IC50 (nM)d CHO-VV 3-2f |

ratio resistant/wild-type CHO-VV 3-2/CHO |

IC50 (nM)d CEM-VLBg |

ratio resistant/wild-type CEM-VLB/CEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 200 | 0.83 | 250 | 1.0 | 320 | 1.3 |

| 26 | 14 | 0.78 | 21 | 1.2 | 23 | 1.2 |

| 31 | 38 | 0.52 | 74 | 1.0 | 87 | 1.3 |

| 35 | 12 | 0.38 | 39 | 1.2 | 32 | 1.6 |

| 36 | 9.3 | 0.52 | 20 | 1.1 | 20 | 1.2 |

| 38 | 8.9 | 0.52 | 20 | 1.2 | 18 | 1.1 |

| 44 | 5.2 | 0.71 | 15 | 2.1 | 9.2 | 1.3 |

| 45 | 3 | 0.41 | 8.2 | 1.1 | 9.5 | 1.3 |

| 46 | 6.1 | 0.36 | 20 | 1.2 | 19 | 1.2 |

| 60 | 86 | 0.37 | 260 | 1.1 | 270 | 1.4 |

| Cola | 140 | 0.64 | 620 | 2.8 | 360 | 46 |

| Pacb | 520 | 3.1 | 140 | 0.82 | 3340 | 12370 |

| Vblc | 6.9 | 0.41 | 66 | 3.9 | 600 | 1579 |

Col, colchicine.

Pac, paclitaxel.

Vbl, vinblastine.

IC50: concentration of drug inhibiting cell growth by 50%.

Paclitaxel-resistant CHO-TAX 5-6 cells.

Colchicine-and vinblastine-resistant CHO-VV 3-2 cells.

Multidrug-resistant leukemia CEM-VLB cells.

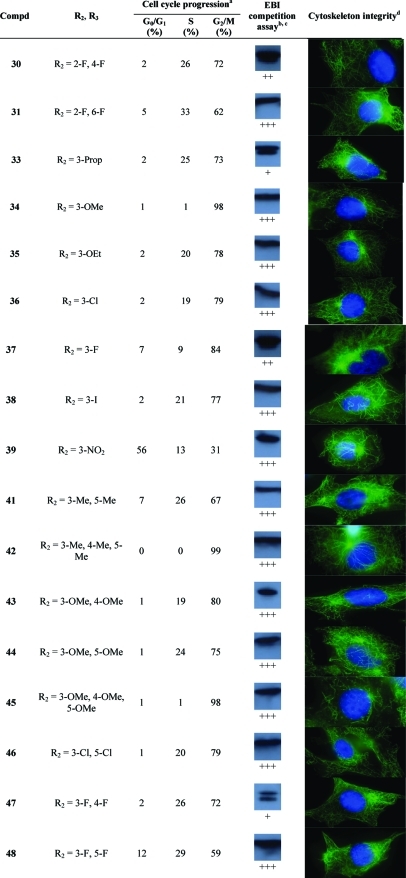

CAM Assay

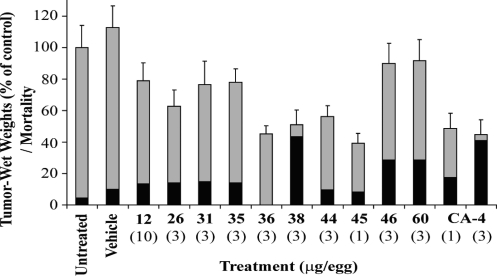

Human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells were grafted onto the chorioallantoic membrane of fertilized chick eggs to assess the antitumoral and the antiangiogenic/antivasculogenic activity of compounds 12, 26, 31, 35, 36, 38, 44, 45, 46, and 60 in the CAM assay (Figure 2). The results shown in Figure 2 were obtained from two independent experiments using at least 10 eggs per experiment. No related toxicity was observed on chick embryos treated with the excipient. Untreated eggs were used as negative controls and for normalization of the results. The drugs were administered iv at 3 μg per egg except for compounds 12 and 45, which were injected at 10 and 1 μg per egg, respectively. Finally, CA-4 was used as positive control and was administered iv at 1 and 3 μg per egg.

Figure 2.

Effect of compounds 12, 26, 31, 35, 36, 38, 44–46, 60, and CA-4 on HT 1080 tumor growth and embryo’s toxicity using the CAM model. Gray bars represent the percentage of tumor-wet weight of tumors treated with and without excipient. Black bars represent the percentage of chick embryo mortality.

Comparative Molecular Field and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analyses (CoMFA and CoMSIA) of PIB-SOs and PPB-SOs

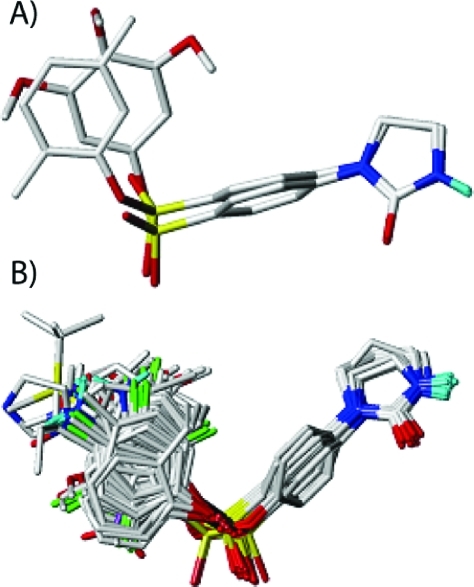

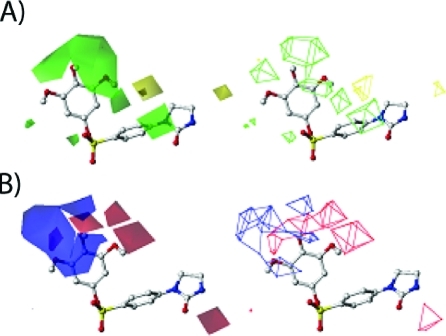

CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses were conducted to establish quantitative structure–activity relationships ruling the antiproliferative activity of PIB-SOs, to understand the mechanisms underlying the binding of PIB-SOs to the C-BS, and to design new and more selective C-BS antagonists. From computational experiments, we developed 3D quantitative structure–activity relationships (3D-QSAR) models. To that end, we used Surflex-Sim which is a 3D molecular similarity optimization and searching program that uses a morphological similarity function and fast pose generation based similarity on a molecule’s shape, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic properties techniques to generate alignments of molecules.(52) Surflex-Sim algorithm was expected to reduce the impact of factors of uncertainty during the generation of the QSAR models. The multiple alignments of most of the active compounds gave the best description of the positions of functional groups leading to the hypothesis generation. Underlying assumption in the alignment is that the compound with better fit to the hypothesis on structural alignment would have better activity. At first, a mutual alignment of the most potent compounds was performed to find a superposition of all input molecules that maximizes the similarity and minimizes the overall volume of the superposition. A hypothesis was generated from this superposition, and that hypothesis will be used as a template to align the set of active molecules. Then the alignment of the data set will be used to generate QSAR models. Compounds 26 and 45 were chosen to generate hypothesis using SYBYL Surflex-Sim mutual alignment module. The alignment hypothesis shows that the groups of same property are well aligned (Figure 3A). Then all PIB-SOs and PPB-SOs were superposed on to the alignment hypothesis using Surflex-Sim flexible superposition module (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Alignment hypothesis generated using Surflex-Sim mutual alignment module from compounds 26 and 45. (B) Superposition of the derivatives of PIB-SOs and PPB-SOs onto the alignment hypothesis.

From the q2 and r2cv values, the analysis that includes the similarity data to the hypothesis improved the r2cv in both CoMFA and CoMSIA models (models A, B, C vs models D, E, F, models G, H, I vs models J, K, L). All three antiproliferative activities in HT-29, M21, and MCF7 cell lines were then used as dependent variables to build CoMSIA and CoMFA models. The optimized parameters and the statistical data in the PLS analysis of six CoMSIA models and six CoMFA models are listed in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 5. Statistical Data of QSAR Method with CoMSIA against Antiproliferative Activity on HT-29, M21, and MCF7 Cells.

| CoMSIA 1 |

CoMSIA 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| model Aa (HT-29) | model Ba (M21) | model Ca (MCF7) | model Da (HT-29) | model Ea (M21) | model Fa (MCF7) | |

| fields and parametersb | CoMSIA FF, similarity, IM2, LogP, MW | CoMSIA FF, similarity, IM2, LogP, MW | CoMSIA FF, similarity, IM2, LogP, MW | CoMSIA FF, MR | CoMSIA FF, MR | CoMSIA FF, MR |

| q2 c | 0.684 | 0.660 | 0.670 | 0.618 | 0.619 | 0.569 |

| r2cv d | 0.697 | 0.668 | 0.680 | 0.612 | 0.609 | 0.551 |

| STEPloo e | 0.520 | 0.541 | 0.518 | 0.584 | 0.579 | 0.601 |

| ONC f | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| SEENoValidation g | 0.350 | 0.352 | 0.352 | 0.308 | 0.302 | 0.318 |

| r2 | 0.863 | 0.859 | 0.852 | 0.893 | 0.896 | 0.879 |

| F h | 71.406 (n1 = 6, n2 = 68) | 95.801 (n1 = 6, n2 = 68) | 70.591 (n1 = 6, n2 = 68) | 94.985 (n1 = 6, n2 = 68) | 97.938 (n1 = 6, n2 = 68) | 82.390 (n1 = 6, n2 = 68) |

Models A, B, and C are optimized CoMSIA models with similarity descriptor. Models D, E, and F are CoMSIA models without similarity descriptor.

CoMSIA FF: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, donor, acceptor.

q2 = cross-validated correlation coefficient from LOO.

r2cv = cross-validated correlation coefficient (10 groups).

STEP = standard error of prediction.

ONC = optimal number of components.

SEE = standard error of estimate.

F = r2/(1 – r2).

Table 6. Statistical Data of QSAR Method with CoMFA against Antiproliferative Activity on HT-29, M21, and MCF7 Cells.

| CoMFA 1 |

CoMFA 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| model Ga (HT-29) | model Ha (M21) | model Ia (MCF7) | model Ja (HT-29) | model Ka (M21) | model La (MCF7) | |

| fields and parametersb | CoMFA FF, similarity, MW | CoMFA FF, similarity, MW | CoMFA FF, similarity, MW | CoMFA FF, LogP | CoMFA FF, LogP | CoMFA FF, LogP |

| q2 c | 0.667 | 0.632 | 0.643 | 0.538 | 0.539 | 0.513 |

| r2cv d | 0.662 | 0.617 | 0.638 | 0.503 | 0.512 | 0.473 |

| STEPloo e | 0.537 | 0.561 | 0.539 | 0.637 | 0.632 | 0.634 |

| STEPcv e | 0.541 | 0.573 | 0.543 | 0.661 | 0.651 | 0.660 |

| ONC f | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| SEENoValidation g | 0.368 | 0.370 | 0.378 | 0.326 | 0.321 | 0.340 |

| r2 | 0.844 | 0.840 | 0.824 | 0.879 | 0.882 | 0.860 |

| F h | 94.467 (n1 = 4, n2 = 70) | 91.731 (n1 = 4, n2 = 70) | 82.105 (n1 = 4, n2 = 70) | 100.253 (n1 = 5, n2 = 69) | 102.718 (n1 = 5, n2 = 69) | 84.958 (n1 = 5, n2 = 69) |

Models G, H, and I are optimized CoMFA models with similarity descriptor. Models J, K, and L are CoMFA models without similarity descriptor.

CoMFA FF: steric, electrostatic.

q2 = cross-validated correlation coefficient from LOO.

r2cv = cross-validated correlation coefficient (10 groups).

STEP = standard error of prediction.

ONC = optimal number of components.

SEE = standard error of estimate.

F = r2/(1 – r2).

Discussion

PIB-SOs Exhibit Potent Antiproliferative Activity on Tumor Cells

PIB-SO and PPB-SO derivatives were divided into four subgroups based on IC50: (1) strong IC50 ranging from 4 to 10 nM (44 and 45); (2) good IC50 ranging from 8.2 to 60 nM (9, 24–26, 28, 30, 31, 33–38, 41, 42, 46, 48, and 55); (3) fair IC50 ranging from 24 to 220 nM (10–12, 16–22, 27, 29, 39, 43, 47, 49, 50, 52, 53, 56, 59–61, and 65); (4) weak IC50 ranging from 128 to >1000 nM (14, 15, 23, 32, 40, 51, 54, 57, 58, 62–64, and 66–81). Compounds 44 and 45 are almost equipotent to combretastatin A-4, which is almost 1000-fold higher than previous CEU derivatives. Table 3 shows that compounds 12, 26, 31, 35, 36, 38, 44–46, and 60 are also very potent against CHO, K562, L1210, P388D1, B16F0, DU 145, HT-1080, MDA-MB-231, SKOV3, and CEM cells.

Antiproliferative Activity of PIB-SOs on Chemoresistant Tumor Cells

Table 4 shows the antiproliferative activities of PIB-SOs 12, 26, 31, 35, 36, 38, 44–46, and 60 on drug-resistant cell lines CHO-TAX 5-6, CHO-VV 3-2, and CEM-VLB. On one hand, CHO-TAX 5-6 cells are resistant to microtubule stabilizers (e.g., paclitaxel) and hypersensitive to microtubule disruptors (e.g., colchicine, vinblastine), while CHO-VV 3-2 cell line are resistant to microtubule disruptors and hypersensitive to microtubule stabilizers.(48) On the other hand, CEM-VLB cells overexpress P-glycoprotein(53) which is responsible for the cellular efflux of drugs and chemoresistance to anticancer drugs such as doxorubicin, etoposide, paclitaxel, and vinblastine.(54) As expected and shown in Table 4, CHO-TAX 5-6 cells that are resistant to paclitaxel were sensitive to PIB-SOs, colchicine, and vinblastine. Beside compound 44, CHO-VV 3-2 cells that are resistant to the colchicine and vinblastine were sensitive to paclitaxel and were unexpectedly sensitive to PIB-SOs. Finally, CEM-VLB cells that are 46-, 12370-, and 1579-fold resistant to the colchicine, vinblastine, and paclitaxel, respectively, were still sensitive to PIB-SOs. These results demonstrate the insensitivity of the antiproliferative activity of PIB-SOs to tubulin mutations and P-glycoprotein overexpression.

PIB-SOs Arrest Cell Cycle Progression in G2/M Phase

Table 2 shows the percentage of M21 cells exhibiting arrest of the cell cycle progression in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases, respectively, after treatment with PIB-SOs for 24 h at 5 times their respective IC50. Control cells treated with 0.5% of DMSO were found to be in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases at 61%, 30%, and 9%, respectively. Incubation with compounds 9, 11, 12, 19–22, 24, 26, 27, 30, 31, 33, 35-38, 41, 43, 44, 46–49, 53, 55, 56, and 65 strongly blocked the cell cycle in G2/M phase; the number of cells in G2/M phase increased by 39–86%. Compounds 10, 16, 17, 25, 28, 34, 42, 45, and 59 blocked almost exclusively the cell cycle in G2/M phase, which is similar to the effect of CA-4.

PIB-SOs Inhibit EBI Binding to the Colchicine-Binding Site

C-BS antagonists such as colchicine, podophyllotoxin,(55) 2-methoxyestradiol,56,57 and CA-4 inhibit the EBI binding to β-tubulin leading to the disappearance of the β-tubulin–EBI adduct formed and detectable by Western blot as a second immunoreacting band of β-tubulin migrating faster than the native β-tubulin.(46) Control cells treated with 0.5% DMSO followed by EBI show an intense β-tubulin–EBI adduct band. With the exception of compound 11, all PIB-SO inhibited the EBI binding to the C-BS. As depicted in Table 2, compounds 12, 17, 25, 33, 47, 49, 53, 55, and 56 weakly interacted with the C-BS. However, compounds 9, 21, 27, 30, 37, and 60 strongly inhibit the formation of the β-tubulin–EBI adduct and compounds 10, 16, 19, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 31, 34–36, 38, 39, 41–46, 48, 59, and 65 abrogate its formation as CA-4 does, suggesting that these molecules are strongly binding to the C-BS and that they act as antimitotics.

PIB-SOs Disrupt the Cytoskeleton of Tumor Cells

Table 2 shows the cytoskeleton of M21 cells treated with PIB-SO at 5 times their respective IC50. The cytoskeleton of control M21 cells treated with DMSO is homogeneous and linear and forms a structured network, while all the cytoskeleton of M21 cells treated with the 41 PIB-SOs tested so far clearly exhibit disrupted microtubular structures.

PIB-SOs Inhibit the Growth of Solid Tumors in the CAM Assay

The growth of solid tumors on the surface of the chorioallantoic membrane depends on the ability of the grafted tumor cells to stimulate angiogenesis and to grow significantly within a 7-day period. HT-1080 human fibrosarcoma cells were used because they produce solid tumors that are sensitive to antiangiogenic and antitumoral drugs.25,58−61 As shown in Figure 2, the excipient was well tolerated by chick embryos when compared to control embryos (10% and 4% mortality, respectively). The selected drugs were tested at 3 μg of drug per egg with the exception of compounds 12 and 45 which were tested also at 10 and 1 μg per egg, respectively. CA-4 was tested at 1 and 3 μg per egg and was used as a positive control exhibiting a strong antivasculogenic activity inhibiting tumor growth by 48% and 45%, respectively. CA-4 exhibited toxicity on chick embryos (18% and 41% mortality, respectively). Compounds 46 and 60 had no significant inhibitory effect on the growth of tumors, and both showed lethal toxicity on 29% of the embryos. Compounds 12, 26, 31, and 35 weakly inhibited the growth of tumor and showed low toxicity (13–15% mortality of embryos). Compounds 36, 44, and 45 had good inhibition of the tumor growth higher than or similar to that of CA-4 (46%, 56%, and 39% reduction compared to controls) with almost no toxicity (0%, 10%, and 8% mortality, respectively). Finally, compound 38 strongly inhibited the growth of tumor but was toxic on 43% of the embryos.

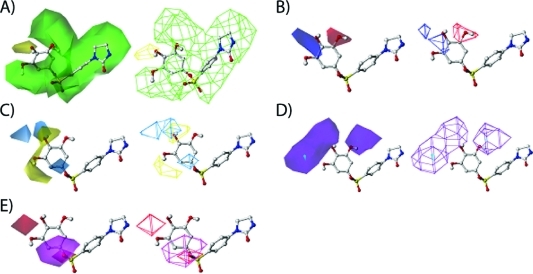

CoMSIA Models

In all CoMSIA models, the contour map of each field has similar coverage areas for different biological activities. For example, in the contour map including HT-29, the optimized CoMSIA models included descriptors of molecular similarity (to the alignment hypothesis), molecular weight, CLogP, and the index of imidazolidin-2-one and the tetrahydropyrimidin-2(1H)-one rings (PIB-SOs and PPB-SOs). The model indicates that PIB-SOs are more preferred to contribute toward higher activity. Models without molecular similarity descriptor (models D, E, and F) had lower r2 in both LOO analysis and cross-validation analysis. This indicates that the alignment hypothesis is reliable and the molecular similarity descriptor is required for a successful model generation. The predicted PIB-SO molecular activities of models A, B, and C are listed in Table 2 in Supporting Information.

In the set of PIB-SO molecules, the most varied position is on the phenyl ring B, so the following discussion would focus on the substitute position on this phenyl ring. Figure 4A shows the favored and disfavored areas of steric field. Most of the area surrounding the molecule was in favor of steric field. Thus, bulky groups have positive contributions to the biological activity on the phenyl group at positions 2, 3, 5, and 6. Bulky groups at position 4 have negative contribution to the biological activity. That explains why most of the compounds 52–63 have bulky substitutes on 4 positions and have lower biological activities. The effects of electrostatic field are shown in Figure 4B. As depicted in the figure, in the area around position 3 of the aromatic ring B electronegative groups increase biological activity while the electropositive group contributes to higher biological activity at positions 4 and 5. The hydrophobicity contributions are shown in Figure 4C. The most favorable areas for hydrophobic moieties are around position 4 and the areas of 5 and 6 positions. In the back and far end of 4 substitute positions, hydrophobic groups are not suggested. In Figure 4D, there is a very small area on the 5 substituted position that is a hydrogen bond donor preferring area (cyan color). Hydrogen bond donor was not preferred in most of the regions around 3-, 4-, and 5-substituted position (purple color). Hydrogen bond acceptor is favored in the area of sulfonate oxygen on one side of the phenyl ring (magenta color in Figure 4E). On the other side of the end group phenyl ring, around the 1 position and between 4 and 5 substituted positions are the regions for which hydrogen bond acceptor is not suggested for high biological activity (red color in Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Contour maps of CoMSIA fields contributing to ligand binding generated by PLS analysis in model A (HT-29). Compound 45 (ball-and-stick model) was shown in the figure as a reference to depict the field region. (A) Contour map of steric field. Green areas present favored steric groups, and yellow areas present disfavored steric groups. (B) Contour map of electrostatic field. Blue areas favored electrostatic field (higher positive charge will increase the activity) and red areas disfavored electrostatic field (lower positive charge will increase the activity). (C) Contour map of hydrophobic field. Yellow areas show favored hydrophobic region, and cyan areas show disfavored hydrophobic region. (D) Contour map of hydrogen bond donor field. Cyan regions are the hydrogen bond donor preferred region, and purple regions are where hydrogen bond donor is not favored. (E) Contour map of hydrogen bond acceptor field. Magenta regions depict the favored hydrogen bond acceptor region, and red regions illustrate the hydrogen bond disfavored region.

CoMFA Models

In CoMFA models, we have included HT-29 activity as an example to illustrate the results shown in Figure 5. Optimized QSAR models included CoMFA fields, molecular similarity data to the hypothesis, and molecular weight. Same as CoMSIA models, molecular similarity descriptor (to the hypothesis) contributes to the successful QSAR models. The predicted PIB-SO molecular activities of models G, H, and I are listed in Table 3 in Supporting Information.

Figure 5.

Contour maps of CoMFA fields contributing to ligand binding generated by PLS analysis in model G (HT-29). Compound 45 (ball-and-stick model) is shown as a reference to depict the field region. (A) Contour map of steric field. Green areas present the favored steric interaction from the ligands, and the yellow areas show the regions that disfavored steric contribution. (B) Contour map of electrostatic field. Blue areas depict favored electrostatic regions; increasing positive charge will contribute to higher activity. Red areas show the disfavored electrostatic areas, where higher ligand binding does not like higher positive charge.

Similar to the results obtained from CoMSIA models, CoMFA models also suggested that most areas in front (the viewer side) of the phenyl ring B prefer a bulky group to make inhibitors have high biological activity (Figure 5A). But CoMFA models did not suggest the disfavored area around the 4-substituted position on the phenyl ring. There are additional areas that CoMFA models suggest to avoid the introduction of bulky groups, about 2 Å away from positions 2 and 3 of the imidazolidone ring. In Figure 5B, the favored electropositive region is much bigger than in the CoMSIA model, which covers the top and front (viewer’s side) regions of 4- and 5-substituted positions of the phenyl ring. In the back of the phenyl ring (away from viewer’s side), substituted 3, 4, and 5 positions of the phenyl ring preferred to have electronegative groups. This area is also larger than the area suggested in CoMSIA models.

Conclusions

We have identified a novel class of antimicrotubule agents designated as substituted phenyl 4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonates (PIB-SOs) that bind to the C-BS on tubulin. PIB-SOs were designed as hybrid entities between CEU and CA-4 analogues where the N-phenyl-N′-(2-chloroethyl)urea pharmacophore was cyclized into a new 1-phenylimidazolidin-2-one pharmacophoric scaffold. PIB-SOs were synthesized in fair to good yields. They exhibit antiproliferative activities in the lower nanomolar range on 16 cancer cell lines and arrest the cell cycle progression in the G2/M phase. Minor structural modifications such as expanding the five-member imidazolidin-2-one ring into the six-member tetrahydropyrimidin-2(1H)-one ring led to a dramatic decrease of the antiproliferative activity, indicating the sensitivity of the new pharmacophore to modifications. Competition assays using EBI and immunofluorescence using anti-β-tubulin antibody confirmed that PIB-SOs are potent antimitotics binding to the C-BS. In addition, the cytotoxicity of PIB-SOs was not affected in cells resistant to colchicine, paclitaxel, and vinblastine and overexpressing the P-glycoprotein. Finally, PIB-SOs 36, 44, and 45 have exhibited potent antitumoral and antiangiogenic activities in the CAM assay that are at least as good as CA-4 but exhibited also a lower toxicity than CA-4 on chick embryos, suggesting these molecules as promising anticancer drugs.

Experimental Section

Biological Methods. Cell Lines Culture

HT-29 human colon carcinoma, MCF7 human breast carcinoma, MDA-MB-231 human breast carcinoma, HT-1080 human fibrosarcoma, K562 human chronic myelogenous leukemia, L1210 murine lymphocytotic leukemia, P388D1 murine macrophages, B16F0 murine melanoma, DU 145 human prostate carcinoma, and SKOV3 human ovarian were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO), colchicine- and vinblastine-resistant CHO-VV 3-2 cells, and paclitaxel-resistant CHO-TAX 5-6 cells were generously provided by Dr. Fernando Cabral (University of Texas Medical School, Houston, TX).47,48 T cell leukemia CEM cells and multidrug-resistant leukemia CEM-VLB were generously provided by Dr. William T. Beck (University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Pharmacy, IL).(49) M21 human skin melanoma cells were provided by Dr. David Cheresh (University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, CA). B16F0, DU 145, HT-29, HT-1080, M21, MCF7, MDA-MB-231, and SKOV3 cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing sodium bicarbonate, high glucose concentration, glutamine, and sodium pyruvate (Hyclone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 5% of calf serum. CHO, CHO-VV 3-2, CHO-TAX 5-6, CEM, CEM-VLB, K562, L1210, and P388D1 cells were cultured in RPMI medium (Hyclone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% of calf serum. The cells were maintained at 37 °C in a moisture-saturated atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Antiproliferative Activity Assay

The antiproliferative activity of PIB-SOs (9–68) and PPB-SOs (69–81) was assessed using the procedure described by the National Cancer Institute for its drug screening program with slight modifications.(45)The 96-well microtiter plates were seeded with 75 μL of tumor cell (for HT-29, 5000 cells; M21, 3500 cells; MCF7, 7500 cells; CHO, 1000 cells; K562, 5000 cells; L1210, 6000 cells; P388D1, 18 000 cells; B16F0, 2000 cells; DU 145, 5000 cells; HT-1080, 3000 cells; MDA-MB-231, 3000 cells; SKOV3, 5000 cells; CEM, 20000 cells; CHO-VV 3-2, 1000 cells; CHO-TAX 5-6, 1000 cells; CEM-VLB, 20000 cells) in appropriate medium. Plates were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. Freshly solubilized drugs in DMSO were diluted in fresh medium, and 75 μL aliquots containing increasing concentrations (0.98–1000 nM) of the drug were added. Plates were incubated for 48 h. Plates containing attached cell lines were then stained with sulforhodamine B. Briefly, cells were fixed by addition of cold trichloroacetic acid to the wells (10% (w/v) final concentration), for 30 min at 4 °C. Plates were washed five times with tap water and dried. Sulforhodamine B solution (50 μL) at 0.1% (w/v) in 1% acetic acid was added to each well, and plates were incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Unbound dye was removed by washing five times with 1% acetic acid. Bonded dye was solubilized in 10 mM Tris base, and the absorbance was read using a μQuant Universal microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek, Winooski, VT) at a wavelength between 530 and 565 nm according to color intensity. For cells in suspension resazurin staining was used. Briefly, supernatant was aspirated and an amount of 100 μL of resazurin at 25 μg/mL in fresh medium was added. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1–3 h according to cell line sensitivity. Fluorescence was read on a FL-500 fluorometer (Biotek, Winooski, VT) using 530 nm for excitation wavelength and 590 nm for emission wavelength. The experiments were performed at least twice in triplicate. The IC50 assay was considered valid when the relative standard deviation was less than 10%.

Cell Cycle Analysis

After incubation of 2.5 × 105 M21 cells with the drugs at 2 and 5 times their respective IC50, for 24 h, the cells were trypsinized, washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in 250 μL of PBS, fixed by the addition of 750 μL of ice-cold ethanol, and stored at −20 °C until use. Afterward, the cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 1000g. Cell pellets were washed with PBS and were resuspended in 450 μL of PBS containing 200 μg/mL RNase. After 5 min, 25 μL of PBS containing 1 mg/mL propidium iodide was added. Mixtures were incubated on ice for 1 h, and then cell cycle distribution was analyzed using an Epics Elite ESP flow cytometer (Coulter Corporation, Miami, FL).

Inhibition of EBI-Binding to β-Tubulin

Six-well plates were seeded with MDA-MB-231 cells at 7 × 105 cells per well and incubated for 24 h. Cells were first incubated in the presence of approximately 1000 times the IC50 of the drugs for 2 h, and afterward they were treated by the addition of EBI (Toronto Research Chemicals, North York, Ontario, Canada) (100 μM, final concentration) for 1.5 h at 37 °C without changing the culture medium, which contains the drug tested. The control cells were treated with 0.5% dimethylsulfoxide. Afterward, floating and adherent cells were harvested using a rubber policeman and centrifuged for 3 min at 8000 rpm. The pellets were washed with 500 μL of cold PBS and stored at −80 °C until use. The cells pellets were resuspended in PBS and lysed by sonication. The protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, Canada). Samples were diluted at 2 mg/mL protein in Laemmli buffer(62) (60 mM Tris-Cl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue). Cell extracts were boiled for 5 min. An amount of 20 μg of proteins from the protein extracts was subjected to electrophoresis using 10% polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes that were incubated with TBSMT (Tris-buffered saline + 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 with 2.5% fat-free dry milk) for 1 h at room temperature and then with the anti-β-tubulin (clone TUB 2.1) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) primary antibody in TBSMT (1:500) for 16 h at 4 °C. Membranes were washed with TBST (tris-buffered saline + 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20) and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated antimouse immunoglobulin (Amersham Canada (Oakville, Canada)) in TBSMT (1:2500) for 2.5 h at room temperature. After the membranes were washed with TBST, detection of the immunoblot was carried out with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent kit provided by Amersham Canada (Oakville, Canada).

Fluorescence Microscopy

M21 cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells per well in six-well plates that contained 22 μm glass coverslips coated with fibronectin (10 μg/mL) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Tumor cells were incubated either with most potent PIB-SOs, CA-4, and compound 6 at 5 times their respective IC50 or with DMSO (0.5%) for 16 h. Afterward, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. After two washes with PBS, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% saponin in PBS and blocked with 3% (w/v) BSA in PBS for 1 h at 37 °C. The cells were then incubated for 2 h at room temperature with the anti-β-tubulin (clone TUB 2.1) in a solution containing 0.1% saponin and 3% BSA in PBS (1:200). The cells were washed five times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in blocking buffer containing anti-mouse IgG Alexa-488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) (1:1000) and 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (2.5 μg/mL in PBS) to stain the cellular nuclei (1:2000). Cells were then mounted on a microscope slide overnight with slow fade reagent (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) before analysis under a Olympus BX51 microscope. Images were captured as 8-bit tagged image format files with a Q imaging RETIGA EXI digital camera driven by Image Pro Express software.

CAM Tumor Assay

Human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells were used to assess the antitumoral activity of PIB-SOs in the CAM assay.58,59,63 Briefly, fertilized chicken eggs purchased from Couvoirs Victoriaville (Victoriaville, Québec, Canada) were incubated for 10 days in a Pro-FI egg incubator fitted with an automatic egg turner before being transferred to a Roll-X static incubator for the rest of the incubation time (incubators were purchased from Lyon Electric, Chula Vista, San Diego, CA). The eggs were kept at 37 °C in a 60% humidity atmosphere for the entire incubation period. On day 10, by use of a hobby drill (Dremel, Racine, WI), a hole was drilled on the side of the egg and a negative pressure was applied to create a new air sac. A window was opened on this new air sac and was covered with transparent adhesive tape to prevent contamination. A freshly prepared cell suspension (40 μL) of HT-1080 (3.5 × 105 cells/egg) cells was applied directly onto the freshly exposed CAM tissue through the window. On day 11, the drugs dissolved in DMSO were extemporaneously diluted in the excipient (cremophor/ethanol 99%/PBS, 6.25/6.25/87.5 v/v). The concentration of DMSO in the excipient was kept below 0.5% to avoid its potential toxicity. The drug dissolved in 100 μL of excipient was injected iv into 10–12 eggs. The eggs were incubated until day 17, at which time the embryos were euthanized at 4 °C followed by decapitation. Tumors were collected, and the tumor-wet weights were recorded. The number of dead embryos and signs of toxicity from the different groups were recorded.

Chemical Procedures. General

Proton NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AM-300 spectrometer (Bruker, Germany). Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million. IR spectra were recorded on a Magna FT-IR spectrometer (Nicolet Instrument Corporation, Madison, WI, U.S.). Uncorrected melting points were determined on an Electrothermal melting point apparatus. HPLC analyses were performed on an Acquity UPLC sample and binary solvent manager equipped with a Quattro Premier XE tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA, U.S.). A Waters BECH C18 reversed-phase column (1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm, 50 °C) was eluted in 7 min with a methanol/water linear gradient containing 0.1% TFA at 0.6 mL/min. The purity of the final compounds was greater than 95%. All reactions were conducted under a dried nitrogen atmosphere. Chemicals were supplied by Aldrich Chemicals (Milwaukee, WI, U.S.) or VWR International (Mont-Royal, Québec, Canada). Liquid flash chromatography was performed on silica gel F60, 60 A, 40–63 μm supplied by Silicycle (Québec, Canada) using a FPX flash purification system (Biotage, Charlottesville, VA, U.S.) and using the indicated solvent mixture expressed as volume/volume ratios. Solvents and reagents were used without purification unless specified otherwise. The progress of all reactions was monitored using TLC on precoated silica gel plates 60 F254 (VWR International, Mont-Royal, Québec, Canada). The chromatograms were viewed under UV light at 254 and/or 265 nm.

General Preparation of Compounds 9–81

Method A

To a stirred solution of the appropriate N-phenyl-N′-(2-chloroethyl)urea derivative (0.4 mmol) in acetonitrile (10 mL) a mixture of aluminum oxide and potassium fluoride (6:4) (4.0 mmol) was added. The suspension was refluxed overnight. After cooling, the mixture was filtered and the solvent evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by recrystallization or flash chromatography on silica gel.

Method B

4-(2-Oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzene-1-sulfonyl chloride or 4-(tetrahydro-2-oxopyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)benzene-1-sulfonyl chloride (8.00 mmol) was suspended in dry methylene chloride (10 mL) under nitrogen atmosphere. Appropriate phenol (8.00 mmol) and triethylamine (8.00 mmol) were successively added dropwise, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The mixture was evaporated and the residue dissolved with ethyl acetate (100 mL). The solution was washed with hydrochloric acid 1 N (100 mL), sodium hydroxide 1 N (100 mL), brine (100 mL), dried over sodium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated to dryness under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Method C

A mixture of the appropriate nitro compound 39, 50, or 62 (1 equiv) dissolved in ethanol 99% (30 mL) was added dropwise Pd/C 10% (0.02 equiv). The nitro compound was reduced under hydrogen atmosphere (38 psi) overnight. The catalyst was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel to give compounds 40, 51, and 63.

2-Tolyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (9)

Method A: recrystallization from methylene chloride/hexanes 1:20). Yield: 88%. Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 95%. White solid. Mp: 166–167 °C. IR ν: 3242, 1715 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.84–7.69 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.44 (s, 1H, NH), 7.31–7.20 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.00–6.96 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.96–3.91 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.49–3.44 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.04 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 147.9, 146.2, 131.7, 131.0, 129.3, 127.3, 127.2, 126.0, 122.0, 116.4, 44.3, 36.3, 15.9. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 333.0889; C16H16N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 333.0909.

3-Tolyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (10)

Method A: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 56%. Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:10). Yield: 97%. White solid. Mp: 168–169 °C. IR ν: 3217, 1704 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.78–7.68 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.16–7.10 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.04–7.02 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.88 (s, 1H, Ar), 6.73–6.70 (m, 1H, Ar), 5.40 (brs, 1H, NH), 4.00–3.95 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.67–3.61 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.29 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.2, 149.6, 145.3, 140.0, 129.6, 129.2, 127.9, 127.6, 122.9, 119.1, 116.6, 44.8, 37.1, 21.2. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 333.0354; C16H16N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 333.0909.

4-Tolyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (11)

Method A: recrystallization from methylene chloride/hexanes 1:20. Yield: 81%. Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 97%. White solid. Mp: 192–193 °C. IR ν: 3252, 1713 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.80–7.70 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.40 (s, 1H, NH), 7.15 (d, 2H, J = 8.3 Hz, Ar), 6.87 (d, 2H, J = 8.3 Hz, Ar), 3.93–3.87 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.46–3.41 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.25 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 163.4, 152.2, 151.3, 142.0, 135.5, 134.6, 130.5, 127.0, 121.5, 49.4, 41.5, 25.6. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 333.0380; C16H16N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 333.0909.

4-Methoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (12)

Method A: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 62%. Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 75%. White solid. Mp: 178–179 °C. IR ν: 3244, 1709 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 7.68–7.60 (m, 4H, Ar), 6.82–6.79 (m, 2H, Ar), 6.72–6.69 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.94–3.89 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.70 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.58–3.53 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 159.1, 158.2, 145.3, 143.0, 129.6, 127.3, 123.3, 116.6, 114.5, 55.5, 44.8, 37.0. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 349.0853; C16H16N2O5S (M+ + H) requires 349.0858.

4-(Dimethylamino)phenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (13)

Method A: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 53%. Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate (8:2). Yield: 17%. White solid. Mp: 206–207 °C. IR ν: 2805, 1711 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 7.64–7.55 (m, 4H, Ar), 6.79 (d, 2H, J = 9.1 Hz, Ar), 6.52 (d, 2H, J = 9.1 Hz, Ar), 3.90–3.85 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.54–3.48 (m, 3H, CH2 and NH), 2.80 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 158.9, 149.3, 145.0, 140.3, 129.7, 128.1, 122.9, 116.6, 112.6, 44.8, 40.6, 37.0. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 362.0071; C17H19N3O4S (M+ + H) requires 362.1175.

4-Hydroxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (14)

Method A: flash chromatography (methylene chloride/ethyl acetate/methanol 8:2:0 to 75:20:5). Yield: 35%. To a stirred solution of 58 (1 equiv) in tetrahydrofuran (10 mL) was added tetrabutylammonium fluoride 1 M in tetrahydrofuran (1.1 equiv). The mixture was stirred overnight. Then hydrochloric acid was added, the appropriate layer was extracted with 3× ethyl acetate, washed with brine, and dried with sodium sulfate, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to afford 14. Yield: 99%. White solid. Mp: 241–242 °C. IR ν: 3440, 1686 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 9.67 (s, 1H, OH), 7.81–7.69 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.41 (s, 1H, NH), 6.80–6.67 (m, 4H, Ar), 3.94–3.89 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.48–3.42 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 157.0, 146.0, 140.9, 129.4, 125.4, 123.0, 116.3, 116.0, 44.2, 36.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 334.9951; C15H14N2O5S (M+ + H) requires 335.0702.

Phenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (15)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 75%. White solid. Mp: 149–151 °C. IR ν: 3262, 1713 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.82–7.73 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.41–7.29 (m, 4H, Ar or NH), 7.03 (s, 1H, Ar or NH), 7.01 (s, 1H, Ar or NH), 3.94–3.89 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.48–3.43 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 149.2, 146.1, 130.0, 129.4, 127.4, 125.3, 122.1, 116.3, 44.2, 36.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 319.0589; C15H14N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 319.0753.

2-Ethylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (16)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 48%. White solid. Mp: 163–164 °C. IR ν: 3264, 1712 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3 and DMSO-d6): δ 7.42–7.35 (m, 4H, Ar), 6.88–6.83 (m, 1H Ar), 6.75–6.73 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.52 (brs, 1H, NH), 6.46–6.41 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.64–3.59 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.28–3.23 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.25 (q, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2), 0.82 (t, 3H, J = 7.6 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3 and DMSO-d6): δ 158.9, 148.0, 145.3, 137.3, 129.8, 129.5, 128.6, 127.1, 126.8, 122.1, 116.7, 44.9, 37.1, 22.8, 14.1. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 347.0495; C17H18N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 347.1066.

2-Propylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (17)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 90%. White solid. Mp: 153–154 °C. IR ν: 3235, 1714 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3 and DMSO-d6): δ 7.38–7.35 (m, 4H, Ar), 6.83–6.72 (m, 3H, Ar), 6.63–6.61 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.56 (s, 1H, NH), 3.61–3.56 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.24–3.19 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.05 (t, 2H, J = 7.7 Hz, CH2), 1.20–1.07 (m, 2H, CH2), 0.50 (t, 3H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3 and DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 147.6, 146.2, 135.1, 130.8, 129.2, 127.3, 127.2, 126.1, 121.8, 116.4, 44.3, 36.3, 31.2, 22.6, 13.8. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 361.0658; C18H20N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 361.1222.

2-Methoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (18)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 76%. White solid. Mp: 183–185 °C. IR ν: 3236, 1715 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.81–7.71 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.40 (s, 1H, NH), 7.29–7.24 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.08–7.05 (m, 2H, Ar), 6.96–6.91 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.95–3.90 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.55 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.49–3.44 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.3, 151.5, 146.0, 137.7, 129.4, 128.4, 126.2, 123.4, 120.6, 116.0, 113.4, 55.6, 44.3, 36.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 349.0858; C16H16N2O5S (M+ + H) requires 348.9406.

2-Ethoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (19)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 64%. White solid. Mp: 169–171 °C. IR ν: 3236, 2907, 1713 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.81–7.70 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.40 (brs, 1H, NH), 7.27–7.22 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.14–7.12 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.05–7.02 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.96–6.91 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.94–3.89 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.81 (q, 2H, J = 7.0 Hz, CH2), 3.46 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.16 (t, 3H, J = 7.0 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 150.7, 146.0, 137.7, 129.3, 128.3, 126.3, 123.6, 120.4, 116.1, 114.1, 63.8, 44.3, 36.3, 14.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 362.9793; C17H18N2O5S (M+ + H) requires 363.1015.

2-Chlorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (20)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 86%. White solid. Mp: 167–169 °C. IR ν: 3255, 2909, 1709 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.85–7.78 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.58–7.54 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.43–7.33 (m, 3H, Ar and NH), 7.27–7.24 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.96–3.91 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.49–3.43 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 146.5, 145.0, 130.9, 129.6, 128.7, 126.5, 125.3, 123.9, 116.4, 44.3, 36.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 353.0363; C15H13ClN2O4S (M+ + H) requires 353.0159.

2-Fluorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (21)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 67%. White solid. Mp: 164–166 °C. IR ν: 3217, 2905, 1698 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.85–7.76 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.45 (brs, 1H, NH), 7.38–7.33 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.26–7.14 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.96–3.91 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.49–3.44 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 146.5, 129.5, 129.1, 129.0, 125.4, 125.3, 124.9, 124.6, 117.5, 117.2, 116.4, 44.3, 36.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 337.0649; C15H13FN2O4S (M+ + H) requires 337.0658.

2-Iodophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (22)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 73%. White solid. Mp: 205–207 °C. IR ν: 3226, 2913, 1703 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.74–7.72 (m, 5H, Ar), 7.33–7.28 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.19–7.17 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.11 (brs, 1H, NH), 6.99–6.94 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.93–3.88 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.53–3.48 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.2, 149.5, 146.1, 139.7, 129.4, 129.3, 128.2, 126.1, 122.3, 116.0, 90.3, 44.2, 36.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 444.9523; C15H13IN2O4S (M+ + H) requires 444.9719.

2-Nitrophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (23)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 0:1). Yield: 83%. White solid. Mp: 181–182 °C. IR ν: 3423, 3113, 1710 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, MeOD and DMSO-d6): δ 7.22–7.16 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.06–7.03 (m, 2H, Ar), 6.97–6.88 (m, 3H, Ar), 6.79–6.73 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.45–6.43 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.24–3.19 (m, 2H, CH2), 8.82–2.77 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (CDCl3, MeOD and DMSO-d6): δ 158.5, 146.7, 143.2, 141.1, 134.5, 129.5, 128.0, 125.8, 125.0, 124.9, 116.5, 44.5, 36.6. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 363.9450; C15H13N3O6S (M+ + H) requires 364.0603.

2,3-Dimethylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (24)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 72%. White solid. Mp: 190–192 °C. IR ν: 3242, 3118, 1716 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.75–7.65 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.17 (brs, 1H, NH), 7.02–6.94 (m, 2H, Ar), 6.74–6.72 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.93–3.89 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.53–3.48 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.19 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.93 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.3, 147.8, 145.8, 138.6, 129.7, 128.9, 128.0, 126.6, 125.7, 119.3, 116.0, 44.2, 36.5, 19.7, 12.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 347.1050; C17H18N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 347.1066.

2,4-Dimethylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (25)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 98%. White solid. Mp: 203–204 °C. IR ν: 3228, 1714 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.84–7.74 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.44 (s, 1H, NH), 7.07–6.99 (m, 2H, Ar), 6.83–6.81 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.96–3.90 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.49–3.43 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.25 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.98 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 146.1, 145.7, 136.5, 132.1, 130.6, 129.3, 127.6, 126.0, 121.7, 116.4, 44.3, 36.3, 20.3, 15.8. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 347.0571; C17H18N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 347.1066.

2,5-Dimethylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (26)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 76%. White solid. Mp: 184–186 °C. IR ν: 3241, 1710 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.84–7.76 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.41 (brs, 1H, NH), 7.15–7.13 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.05–7.02 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.86 (s, 1H, Ar), 3.95–3.90 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.49–3.43 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.24 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.94 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 147.6, 146.2, 136.8, 131.3, 129.2, 127.8, 127.6, 126.1, 122.5, 116.4, 44.3, 36.3, 20.4, 15.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 347.1051; C17H18N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 347.1066.

2,4,5-Trimethylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (27)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 69%. White solid. Mp: 204–205 °C. IR ν: 3232, 2917, 1710 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.74–7.64 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.16 (brs, 1H, NH), 6.86 (s, 1H, Ar), 6.71 (s, 1H, Ar), 3.93–3.88 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.53–3.48 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.13 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.11 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.88 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.3, 145.7, 145.6, 134.8, 134.8, 132.1, 128.9, 127.5, 126.8, 122.7, 116.0, 44.2, 36.5, 19.0, 18.7, 15.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 361.1190; C18H20N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 361.1222.

2,4,5-Trichlorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (28)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 62%. White solid. Mp: 186–187 °C. IR ν: 3204, 1710 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 8.03 (s, 1H, Ar), 7.84–7.83 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.60 (s, 1H, Ar), 7.47 (brs, 1H, NH), 3.96–3.91 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.49–3.44 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.1, 146.9, 144.0, 131.7, 130.9, 130.7, 129.8, 126.6, 125.7, 124.5, 116.5, 44.3, 36.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 420.8198; C15H11Cl3N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 420.9583.

2,4,6-Trichlorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (29)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 7:3). Yield: 75%. White solid. Mp: 254–255 °C. IR ν: 3202, 1711 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3 + MeOD): δ 7.92 (d, 2H, J = 9.0 Hz, Ar), 7.73 (d, 2H, J = 9.0 Hz, Ar), 7.33 (s, 2H, Ar), 4.01–3.96 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.64–3.59 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (CDCl3 + MeOD): δ 159.9, 149.8, 145.7, 137.7, 130.9, 129.8, 129.1, 119.6, 116.7, 44.8, 36.9. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 420.9216; C15H11Cl3N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 420.9583.

2,4-Difluorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (30)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 85%. White solid. Mp: 179–183 °C. IR ν: 3236, 1722 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.73–7.64 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.09–6.80 (m, 3H, Ar), 5.06 (br s, 1H, NH), 3.93–3.88 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.54–3.49 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.2, 146.1, 129.1, 126.3, 125.2, 125.0, 116.0, 115.8, 111.4, 111.4, 111.1, 111.1, 105.5, 105.2, 105.1, 104.8, 44.2, 36.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 355.0443; C15H12F2N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 355.0564.

2,6-Difluorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (31)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 81%. White solid. Mp: 187–189 °C. IR ν: 3240, 1732 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.75 (s, 4H, Ar), 7.27–7.17 (m, 2H, Ar or NH), 7.00–6.95 (m, 2H, Ar or NH), 3.95–3.90 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.54–3.49 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.2, 157.2, 157.1, 153.8, 153.8, 146.2, 129.1, 127.8, 127.7, 127.6, 125.7, 125.6, 116.1, 112.4, 112.4, 112.4, 112.2,112.2, 112.1, 44.2, 36.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 355.0549; C15H12F2N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 355.0564.

Perfluorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (32)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 75%. White solid. Mp: 217–218 °C. IR ν: 3258, 1711 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.93–7.86 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.51 (brs, 1H, NH), 3.99–3.94 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.50–3.45 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 164.2, 146.4, 146.3, 129.8, 116.9, 116.8, 44.8, 36.8. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 409.0188; C15H9F5N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 409.0282.

3-Propylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (33)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 80%. White solid. Mp: 144–145 °C. IR ν: 3257, 2951, 1714 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.72–7.60 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.18–7.12 (m, 2H, Ar and NH), 7.02–7.00 (m, 1H, Hz, Ar), 6.73–6.68 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.91–3.86 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.52–3.47 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.46 (t, 2H, J = 7.7 Hz, CH2), 1.47 (m, 2H, CH2), 0.79 (t, 3H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.2, 149.1, 145.7, 144.2, 129.0, 126.9, 125.9, 121.8, 119.1, 116.0, 44.2, 36.9, 36.4, 23.7, 13.2. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 361.1315; C18H20N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 361.1222.

3-Methoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (34)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 70%. White solid. Mp: 139–140 °C. IR ν: 3219, 1712 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 7.73–7.62 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.13–7.08 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.74–6.71 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.54–6.47 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.93–3.89 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.68 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.59–3.54 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.60 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 160.4, 159.1, 150.5, 145.4, 129.9, 129.6, 127.5, 116.6, 114.3, 113.0, 108.3, 55.5, 44.8, 36.9. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 348.9994; C16H16N2O5S (M+ + H) requires 349.0858.

3-Ethoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (35)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 81%. White solid. Mp: 143–145 °C. IR ν: 3255, 2898, 1713 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.79–7.63 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.16–7.09 (m, 2H, Ar and NH), 6.75–6.71 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.47–6.42 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.92–3.86 (m, 4H, 2 × CH2), 3.53–3.47 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.30 (t, 3H, J = 6.9 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 159.3, 158.2, 150.0, 145.8, 129.6, 129.0, 125.9, 116.0, 113.6, 113.0, 108.4, 63.3, 44.2, 36.5, 14.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 363.1002; C17H18N2O5S (M+ + H) requires 363.1015.

3-Chlorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (36)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 77%. White solid. Mp: 160–162 °C. IR ν: 3223, 1707 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.85–7.77 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.46–7.42 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.20 (s, 1H, NH), 7.02–6.98 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.96–3.90 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.49–3.44 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 149.6, 146.4, 133.7, 131.4, 129.5, 127.6, 124.7, 122.5, 121.0, 116.4, 44.2, 36.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 353.0349; C15H13ClN2O4S (M+ + H) requires 353.0363.

3-Fluorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (37)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 56%. White solid. Mp: 157–158 °C. IR ν: 3243, 1712 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 7.68–7.58 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.21–7.13 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.91–6.85 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.71–6.66 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.91–3.86 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.54–3.53 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 160.9, 159.1, 150.1, 145.6, 130.4, 129.5, 126.9, 118.1, 116.7, 114.2, 110.4, 44.8, 36.9. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 337.0745; C15H13FN2O4S (M+ + H) requires 337.0658.

3-Iodophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (38)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 80%. White solid. Mp: 182–184 °C. IR ν: 3250, 2906, 1711 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.76–7.64 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.57 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar), 7.34–7.32 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.25 (s, 1H, NH), 7.04 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar), 6.90–6.86 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.93–3.88 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.52–3.47 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.2, 149.3, 146.1, 135.8, 131.0, 129.1, 125.2, 121.4, 116.1, 93.5, 44.2, 36.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 444.9700; C15H13IN2O4S (M+ + H) requires 444.9719.

3-Nitrophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (39)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 98%. White solid. Mp: 152–153 °C. IR ν: 3248, 1713 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.10–7.66 (m, 6H, Ar), 7.50–7.45 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.35–7.32 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.97–3.92 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.63–3.57 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.0, 149.7, 146.0, 130.5, 129.7, 128.9, 128.4, 126.3, 122.0, 118.0, 116.8, 44.8, 36.9. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 364.0343; C15H13N3O6S (M+ + H) requires 364.0603.

3-Aminophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (40)

Method C: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/methanol 9:1). Yield: 32%. White solid. Mp: 184–185 °C. IR ν: 3233, 1709 cm–1. 1H NMR (acetone-d6): δ 7.87–7.73 (m, 4H, Ar), 6.96 (t, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz, Ar), 6.56–6.53 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.41–6.40 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.18–6.15 (m, 1H, Ar), 4.92 (s, 1H, NH), 4.04–4.00 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.64–3.59 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (acetone-d6): δ 159.2, 150.8, 147.0, 130.4, 130.2, 130.0, 117.0, 117.0, 113.5, 110.2, 108.4, 45.3, 37.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 334.0578; C15H15N3O4S (M+ + H) requires 334.0862.

3,5-Dimethylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (41)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 75%. White solid. Mp: 200–203 °C. IR ν: 3230, 1711 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.83–7.75 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.41 (s, 1H, Ar or NH), 6.95 (s, 1H, Ar or NH), 6.65 (s, 2H, Ar or NH), 3.95–3.89 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.48–3.43 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.21 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 149.1, 146.1, 139.4, 129.3, 128.7, 125.6, 119.4, 116.3, 44.3, 36.3, 20.7. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 347.0825; C17H18N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 347.1066.

3,4,5-Trimethylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (42)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 0:1 to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 79%. White solid. Mp: 211–212 °C. IR ν: 3223, 2910, 1713 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.83–7.75 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.42 (s, 1H, NH), 6.67 (s, 2H, Ar), 3.95–3.90 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.49–3.44 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.17 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3), 2.07 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.3, 146.4, 146.0, 137.8, 134.0, 129.3, 125.8, 120.4, 116.3, 44.3, 36.3, 20.2, 14.7. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 361.1224; C18H20N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 361.1222.

3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (43)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 0:1). Yield: 70%. White solid. Mp: 156–158 °C. IR ν: 3235, 2969, 1710 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 7.66–7.58 (m, 4H, Ar), 6.63–6.60 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.48–6.47 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.38–6.34 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.90–3.85 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.73 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.66 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.54–3.50 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.32 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (CDCl3 and MeOD): δ 159.1, 149.2, 147.8, 145.4, 143.1, 129.6, 127.2, 116.6, 113.8, 110.9, 106.5, 56.0, 56.0, 44.8, 36.9. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 378.9391; C17H18N2O6S (M+ + H) requires 379.0964.

3,5-Dimethoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (44)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 71%. White solid. Mp: 219–221 °C. IR ν: 3235, 1711 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.85–7.78 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.43 (s, 1H, NH), 6.46–6.45 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.18–6.17 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.95–3.90 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.68 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3), 3.49–3.44 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 160.8, 158.2, 150.6, 146.2, 129.5, 125.3, 116.4, 100.6, 99.0, 55.6, 44.3, 36.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 379.0945; C17H18N2O6S (M+ + H) requires 379.0964.

3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (45)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 7:3). Yield: 31%. Mp: 191–192 °C. IR ν: 3201, 1706 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.86–7.80 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.42 (s, 1H, NH), 6.31 (s, 2H, Ar), 3.95–3.90 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.65 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3), 3.63 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.49–3.44 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 153.1, 146.2, 145.1, 136.3, 129.6, 125.2, 116.4, 100.0, 60.1, 56.1, 44.3, 36.2. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 409.1068; C18H20N2O7S (M+ + H) requires 409.1070.

3,5-Dichlorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (46)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 64%. White solid. Mp: 179–181 °C. IR ν: 3236, 1709 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.87–7.80 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.66 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.46 (s, 1H, NH), 7.21–7.20 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.97–3.91 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.49–3.44 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 149.7, 146.6, 134.7, 129.6, 127.6, 124.3, 121.7, 116.4, 44.2, 36.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 386.9956; C15H12Cl2N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 386.9973.

3,4-Difluorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (47)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 78%. White solid. Mp: 182–184 °C. IR ν: 3230, 2918, 1716 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.77–7.51 (m, 5H, Ar and NH), 7.27–7.18 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.03–6.96 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.77–6.72 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.93–3.83 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.51–3.43 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.8, 158.1, 146.2, 141.6, 138.9, 129.2, 126.2, 124.8, 118.8, 118.8, 118.7, 118.7, 117.7, 117.5, 116.2, 115.8, 112.4, 112.1, 44.5, 44.2, 36.6, 36.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 354.9966; C15H12F2N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 355.0564.

3,5-Difluorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (48)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 90%. White solid. Mp: 172–174 °C. IR ν: 3225, 1716 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.75–7.66 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.07 (s, 1H, NH), 6.81–6.74 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.59–6.55 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.93–3.87 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.54–3.48 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 164.0, 163.8, 160.7, 160.5, 158.2, 150.2, 146.1, 129.1, 125.0, 116.1, 106.4, 106.3, 106.1, 106.0, 103.0, 102.7, 102.3, 44.2, 36.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 355.0141; C15H12F2N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 355.0564.

3,4,5-Trifluorophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (49)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 99%. White solid. Mp: 178–180 °C. IR ν: 3238, 2914, 1714 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.78–7.67 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.24 (s, 1H, NH), 6.84–6.77 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.94–3.89 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.53–3.48 (m, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.1, 152.0, 151.9, 151.9, 151.8, 148.7, 148.6, 148.5, 148.5, 146.4, 143.8, 143.8, 143.7, 140.3, 140.1, 139.9, 136.8, 129.2, 124.5, 116.2, 108.0, 107.9, 107.8, 107.7, 44.2, 36.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 372.9821; C15H11F3N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 373.0470.

3-Methyl-4-nitrophenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (50)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 65%. White solid. Mp: 215–216 °C. IR ν: 3225, 1713 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 8.03 (d, 1H, J = 8.9 Hz, Ar), 7.85–7.81 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.45 (s, 1H, NH), 7.32–7.31 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.10–7.07 (m, 1H, Ar), 3.95–3.90 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.48–3.43 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.49 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 151.5, 147.3, 146.5, 135.7, 129.5, 126.7, 126.0, 124.7, 120.6, 116.5, 44.2, 36.3, 19.5. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 378.0916; C16H15N3O6S (M+ + H) requires 378.0760.

4-Amino-3-methylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (51)

Method C: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/methanol 9:1). Yield: 31%. yellow solid. Mp: 160–162 °C. IR ν: 3228, 1709 cm–1. 1H NMR (acetone-d6): δ 7.87–7.70 (m, 4H, Ar), 6.75–6.69 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.57–6.37 (m, 2H, Ar), 4.55 (s, 1H, NH), 4.06–4.00 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.65–3.59 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.29 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (acetone-d6): δ 159.1, 146.9, 146.0, 141.4, 130.1, 124.6, 124.5, 120.9, 120.7, 116.9, 114.8, 45.3, 37.4, 17.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 348.1060; C16H17N3O4S (M+ + H) requires 348.1018.

4-Ethylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (52)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 79%. White solid. Mp: 155–157 °C. IR ν: 3230, 1715 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.83–7.74 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.42 (s, 1H, NH), 7.21 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar), 6.92 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar), 3.95–3.90 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.49–3.43 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.58 (q, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2), 1.15 (t, 3H, J = 7.5 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 158.2, 147.2, 146.1, 142.9, 129.4, 129.2, 125.4, 121.9, 116.3, 44.2, 36.3, 27.5, 15.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 347.0906; C17H18N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 347.1066.

4-Propylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (53)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 78%. White solid. Mp: 198–200 °C. IR ν: 3208, 2955, 1712 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.68–7.60 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.02 (s, 1H, Ar or NH), 6.99 (s, 1H, Ar or NH), 6.79–6.76 (m, 3H, Ar), 3.91–3.86 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.54–3.49 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.47 (t, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2), 1.59–1.47 (m, 2H, CH2), 0.84 (t, 3H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.3, 147.1, 145.4, 141.2, 129.0, 129.0, 126.3, 121.5, 116.0, 44.2, 36.8, 36.5, 23.8, 13.3. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 361.0652; C18H20N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 361.1222.

4-sec-Butylphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (54)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 74%. White solid. Mp: 179–180 °C. IR ν: 3245, 1711 cm–1. 1H NMR (acetone-d6): δ 7.90–7.73 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.19 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz, Ar), 6.95 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz, Ar), 6.40 (brs, 1H, NH), 4.06–4.01 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.65–3.60 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.65–2.58 (m, 1H, CH), 1.58–1.23 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.18 (d, 3H, J = 6.9 Hz, CH3), 0.77 (t, 3H, J = 7.4 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (acetone-d6): δ 159.0, 147.6, 146.6, 145.3, 129.7, 128.1, 127.9, 122.1, 116.6, 44.9, 41.1, 37.1, 31.1, 21.7, 12.1. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 375.0776; C19H22N2O4S (M+ + H) requires 375.1379.

4-Ethoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (55)

Method B: flash chromatography (ethyl acetate to ethyl acetate/methanol 95:5). Yield: 76%. White solid. Mp: 185–187 °C. IR ν: 3236, 2908, 1710 cm–1. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 7.70–7.58 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.01 (s, 1H, NH), 6.79–6.75 (m, 2H, Ar), 6.72–6.68 (m, 2H, Ar), 3.95–3.86 (m, 4H, 2 × CH2), 3.53–3.48 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.32 (t, 3H, J = 7.0 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6 and CDCl3): δ 158.3, 157.1, 145.6, 142.4, 129.0, 125.9, 122.9, 115.9, 114.6, 63.3, 44.2, 36.5, 14.4. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 363.0692; C17H18N2O5S (M+ + H) requires 363.1015.

4-Propoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (56)

Method B: flash chromatography (methylene chloride to methylene chloride/ethyl acetate 8:2). Yield: 56%. White solid. Mp: 156–157 °C. IR ν: 3226, 1711 cm–1. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.74–7.65 (m, 4H, Ar), 6.87–6.83 (m, 2H, Ar), 6.76–6.72 (m, 2H, Ar), 5.73 (s, 1H, NH), 3.98–3.93 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.84 (t, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz, CH2), 3.66–3.60 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.80–1.71 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.00 (t, 3H, J = 7.4 Hz, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 158.9, 157.8, 145.3, 142.9, 129.7, 127.6, 123.3, 116.6, 115.0, 69.9, 44.9, 37.1, 22.5, 10.5. HRMS (ES+) m/z found 377.0320; C18H20N2O5S (M+ + H) requires 377.1171.

4-Butoxyphenyl-4-(2-oxoimidazolidin-1-yl)benzenesulfonate (57)