Abstract

Background

There is broad consensus that the eating disorders (EDs) of anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) stem from fundamental disturbances in identity development, but theoretically based empirical support is lacking.

Objective

To extend work on the identity impairment model (Stein, 1996) by investigating the relationship between organizational properties of the self-concept and change in disordered eating behaviors (DEB) in an at-risk sample of college women transitioning between freshman and sophomore years.

Method

The number, valence and organization of self-schemas, availability of a fat body weight self-schema, and DEB were measured at baseline in the freshman year, and 6 and 12 months later in a community-based sample of college women engaged in subthreshold DEB (n = 77; control: n = 41). Repeated measures ANOVAs were used to examine group differences and hierarchical regression analyses were used to predict disordered eating behaviors.

Results

Women in the DEB group had more negative self-schemas at baseline and showed information processing evidence of a fat self-schema compared to the controls. The groups did not differ in the number of positive self-schemas or interrelatedness. The number of negative self-schemas predicted increases in the level of DEB at 6- and 12-month follow-up, and these effects were mediated through the fat self-schema. The number of positive self-schemas predicted the fat self-schema score but was not predictive of increases in DEB. Interrelatedness of the self-concept was not a significant predictor in this model.

Discussion

Impairments in overall collection of identities are predictive of the availability in memory of a fat self-schema, which in turn is predictive of increases in DEB during the transition to college in a sample of women at risk for an ED. Therefore, organizational properties of the self-concept may be an important focus for effective primary and secondary prevention.

Keywords: self-concept, theoretical model, body-image

The proposition that the eating disorders (EDs) of anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) stem from fundamental disturbances in identity development is a basic tenet in a diverse array of ED theories ranging from early psychoanalytic theories to cultural and feminist approaches (for a review see Stein & Corte, 2003). Yet related studies generally have failed to converge into a coherent and compelling set of findings necessary to explicate the link between the self-concept and ED symptomatology. One key factor that has contributed to this lack of progress is that the core self-related constructs in the theories lack clear theoretical and operational definitions. Even the basic distinction as to whether the theory focuses on the process of identity development, characteristics of the actual array of identities (the products of identity development), or the global attitude toward the self often is specified unclearly, making the focus of the theory difficult to discern.

In a recent study, Stein and Corte (2007) addressed the problem of unclear theoretical specification by using the schema model of the self-concept (Markus, 1977) to investigate the content and organization of self-cognitions that distinguished women with AN and BN from controls. In this model, identity formation is conceptualized as a developmental process that results in a stable but evolving set of memory structures about the self that collectively are referred to as the self-concept (Westen & Heim, 2003). The self-concept is a complex, multidimensional cognitive structure comprised of multiple self-schemas. Self-schemas are individual organizations of knowledge about the self in specific domains of emotional and behavioral commitment (Markus & Wurf, 1987). Once established in memory, self-schemas serve as organizing templates that influence: 1) speed of processing of self-relevant information with schema consistent decisions made more rapidly and schema-inconsistent decisions made more slowly (Green & Sedikides, 2001; Kendzierski & Sheffield, 2000), 2) recall of self-relevant stimuli (Markus, 1977), 3) the direction of attention, 4) inferential processes (Markus, Smith, & Moreland, 1986). In addition, self-schemas motivate and regulate behavior (Clemmey & Nicassio, 1997; Kendzierski & Whitaker, 1997; Sheeran & Orbell, 2000).

Studies have shown that the valence and organization of self-schemas influence emotional and behavioral self-regulation. Positively valenced self-schemas enhance behavioral performance in a domain (Cross & Markus, 1994; Froming, Nasby, & McManus, 1998; Kendzierski & Costello, 2004), while negatively valenced self-schemas are associated with negative affect, behavioral avoidance, and inhibition (Cyranowski & Andersen, 1998; Lips, 1995). Furthermore, individual differences in the way self-schemas are organized influence their pattern of activation in memory. Interrelatedness refers to the extent to which schemas are linked together in memory (Linville, 1987). Contemporary models of cognition suggest that repeated activation of a specific subset of memory units leads to their functioning as an organized chronically accessible interrelated cluster. A highly interrelated collection of self-schemas functions as a single unit and consequently reflects a less differentiated and complex self (Niedenthal & Beike, 1997; Nowak, Vallacher, Tesser, & Borkowski, 2000). Individuals with high interrelatedness among their self-schemas are: 1) less able to tolerate challenging social feedback and respond to the threat with less effective coping strategies, 2) react to stressors with decreases in mood and self-esteem, and 3) experience more physical illness in response to stress than persons who have many independent self-schemas available in memory (Dixon & Baumeister, 1991; Evans, 1994; Linville, 1987).

Based on the self-schema findings, Stein (1996) developed an identity impairment model that focuses on the number and organization of the total collection of self-schemas available in memory as a primary source of ED symptomatology and tested it in a sample of 26 women with AN, 53 women with BN, and 32 women with no history of a mental disorder including AN and BN (Stein & Corte, 2007). Outcome measures included the Eating Disorder Inventory (Garner, 1991) and a health behavior questionnaire designed to measure a full range of DEB over the last month. Results supported the model and showed that women with AN and BN had fewer positive and more negative self-schemas and higher interrelatedness compared to controls. Women in the BN group demonstrated a pattern of information processing suggesting that they have a fat self-schema available in memory but women in the AN group did not. Regression analyses showed that two of the self-concept variables (positive and negative self-schemas) indirectly influenced ED attitudes and behaviors through the availability of a fat self-schema, while the third self-concept variable (interrelatedness) had a direct influence on DEB and on one of the ED attitudes, drive for thinness.

Although the Stein and Corte (2007) results support the identity impairment model, the fact that women in the sample already had a diagnosable ED raises questions about the direction of the relationship. One plausible competing hypothesis is that the ED attitudes and behaviors caused the observed differences in the self-concept properties. Furthermore, since 84% of the participants had a history of treatment for their ED, it is possible that the observed self-concept properties are a product of treatment rather than a cause of the disorders. To address these competing hypotheses, a 12-month longitudinal study was designed to replicate the original study with a community-based sample of college freshmen women who engaged in subthreshold levels of DEB and had no history of treatment for their behaviors.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between the content and organization of self-schemas and the unfolding of DEB over time in women at risk for developing an eating disorder. More specifically, the effects of the number of valenced self-schemas and their level of interrelatedness on changes in eating disordered behavioral symptoms were examined in a sample of college freshman women as they transitioned from their freshman into their sophomore year. Three hypotheses were tested: 1) women engaging in subclinical levels of ED behavior will have a self-concept characterized by few positive self-schemas, many negative self-schemas, high interrelatedness, and availability of a fat self-schema, 2) a self-concept comprised of few positive self-schemas, many negative self-schemas, and high interrelatedness will predict the availability of a fat self-schema in memory, which in turn will predict increases in ED behavior, and 3) self-concept properties at baseline will predict increases in the fat self-schema over time. Finally, we tested the competing hypothesis that the self-concept properties are an outcome of ED behaviors rather than a determinant of ED behaviors.

Methods

Design

A 12-month longitudinal design was used to study two groups of women across the college freshman to sophomore year. Self-concept properties were measured at two time points (baseline in freshman year and 12-month follow-up in sophomore year) and ED symptoms were measured at 6-month intervals (baseline, 6 months, and 12 months). The college freshman to sophomore developmental transition was selected for study because it is a peak period of onset of ED symptoms and a period when symptoms consolidate into a stable disorder (Striegel-Moore, Dohm, Pike, Wilfley & Fairburn, 2002; Taylor et al., 2006).

Participants

Participants included two groups of college freshmen women from a large Midwestern university. The DEB group was comprised of 77 college freshmen women with no history of ED treatment who were currently engaging in at least one ED behavior (food restricting or fasting; binge eating; vomiting; exercising for more than 1 hour per day; or using laxatives, diuretics, or diet pills to control weight), were amenorrheic for at least 3 consecutive months, or both. The control group was comprised of 41 college freshman women who had no history of DEB and no weight concerns.

Letters describing the study were sent to all incoming freshmen women and flyers were posted in dorms and across campus. Potential participants contacted the research office and were screened by phone to determine eligibility. Women with any history of ED treatment or taking any medication (except for birth control pills) were not eligible.

Measures

Number of Valenced Self-schemas

The number of valenced self-schemas was measured using an open-ended format questionnaire developed to measure organizational properties of cognitive structures (Zajonc, 1960) and employing a methodology developed by Markus (1977) to identify self-schemas. Participants were given a stack of 52 blank index cards labeled A through ZZ and were asked to write down all of the attributes that are "important to who you are.” They were asked to write one self-defining attribute on each card and encouraged to use as many or as few cards as necessary to thoroughly describe themselves. Next, they were asked to rate the self-descriptiveness of each self-generated attribute on an 11-point scale and then to rate “the importance of the attribute to how you see yourself” also on an 11-point scale. Finally, they were asked to rate each attribute according to whether “you view the attribute as positive, negative or neutral.” In keeping with previous work on self-schematicity (Kendzierski, 1988; Kendzierski & Sheffield, 2000, Kendzierski & Whitaker, 1997; Markus, 1977), attributes that were rated as highly self-descriptive and highly important (i.e., rated 8–11 on self-descriptiveness and importance scales) were classified as a self-schema. The number of positive (negative, neutral) self-schemas was computed by totaling the number of self-descriptors that met the criteria for a self-schema and were rated as positive (negative, neutral). The validity of the self-descriptiveness and importance ratings as a means to identify self-schemas has been demonstrated (Kendzierski & Whitaker, 1997; Markus, 1977). A moderate level of retest reliability has been shown for the total number of self-schemas at 2-week (r[36] = .26, p = .06) and 18-month (r[34] = .49, p < .01) intervals.

Interrelatedness

Degree of interrelatedness among the self-schemas was determined using the card-sorting task developed by Zajonc (1960) that asks participants to focus on one self-descriptor at a time and list “all the characteristics that would change if that [targeted] characteristic was changed, absent, or untrue of you.” Subjective dependencies were standardized to control for varying numbers of self-descriptors. Scores range between 0 and 1 with higher values indicating higher interrelatedness. Stein (1990) found a predicted negative correlation between interrelatedness and Linville’s (1985) self-complexity score demonstrating criterion validity. A high level of retest reliability was found for the interrelatedness measure at 2 weeks (r[36] = .64, p < .001) and a moderate level at 18 months (r[34] = .34, p < .05; Stein, 1995).

Fat Self-Schema: Information Processing Indicator

The availability of a fat self-schema in memory was examined using information processing indicators (trait adjective ratings and response latency times) (Markus, 1977; Rogers, Kuiper, & Kirker, 1977) at baseline and a closed-ended self-schema measure (semantic differential scale) at 12-month follow-up. Stimuli for the information processing task were 63 appearance-related adjectives used previously by Markus et al. (1987) to measure body-weight self-schemas. The fat scale consisted of 10 adjectives (pleasantly-plump, chubby, strapping, roly-poly, overweight, dumpy, obese, stout, fat, pudgy). Internal consistency based on the self-endorsements was α =.87. Ten adjectives (muscular, youthful, short, fair, freckled, blue-eyed, brown-eyed, blond, bow-legged, stooped) that were not correlated with the fat scale score were used to construct control scales for the endorsement rating and response latencies.

Participants who failed to respond to at least 7 of the 10 fat words and 7 of the 10 control words within the allotted word presentation time were deleted from the latency analyses (n = 7; 6 DEB and 1 control). Separate fat and control word endorsement scores that reflect the proportion of the total number of fat and control items endorsed as Me were computed for each subject. Mean response latency time scores for the fat and control words were calculated for each subject separately for the Me and Not Me endorsements. A response latency time score (RLT) was computed as long as one RLT was obtained for the scale.

Fat Self-Schema: Closed-Ended Self-Report Measure

To minimize participant burden and simplify measurement of the availability of the fat self-schema at the 12-month follow-up, a closed-ended self-schema measure was administered at baseline (to establish validity of the measure) and 12 months. The closed-ended self-schema scale consists of 14 bipolar sets of trait adjectives that are rated on an 11-point scale for self-descriptiveness and importance. One scale relevant to body-weight (thin-fat) is embedded in the 14-item scale. Extreme endorsements on the fat end of the scale (8–11 on self-descriptiveness and importance) were used to determine availability of a fat self-schema (Markus, 1977). To establish validity of the closed-ended measure to determine availability of a fat self-schema, we examined relationships between the information processing indicators and the closed-ended measure of the fat self-schema at baseline. As expected, women identified as fat schematic endorsed a significantly greater proportion of fat-related adjective as self-descriptive (53% vs. 12%, p < .001), response latency times for Me endorsements were faster (1.17 sec vs. 1.32 sec, p < .01), and Not Me endorsements were slower (1.26 sec vs. 1.05 sec, p < .001) than those identified as fat aschematic. Together these results provide evidence to support the closed-ended self-schema measure as a valid indicator of fat self-schema availability.

Eating disorder attitudes

The three subscales from the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI; Garner, 1991) that are focused on body weight/shape were used to measure ED attitudes (body dissatisfaction, drive for thinness, and bulimia). Criterion-related and concurrent validity of the subscales have been shown with clinical and nonclinical samples (Garner, 1991). Internal consistency of the subscales, using Cronbach's Alpha, examined in large samples of ED women range between .80 and .93 (Garner, 1991). Retest reliability has also been shown over 3-week intervals in normal and symptomatic college samples (Body Dissatisfaction r = .96 –.97, Drive for Thinness r = .85 to .93; Bulimia: r = .90 to.92) (Garner, Olmstead, & Polivy, 1983; Wear & Pratz, 1987). For this sample, alpha coefficients for the three scales ranged from .82 to .96.

Disordered eating behaviors

A health behavior questionnaire was used to measure the frequency of engagement in the preceding month in a full range of DEB including fat/calorie restricting and fasting, excessive exercise (>1 hour per day), bingeing, vomiting, laxative, diuretic, and diet pill use. The duration of amenorrhea was measured also. Each behavior was measured on a 5-point scale ranging from no involvement to daily involvement. For amenorrhea, the 5-point scale ranged from regular cycles to 12 or more consecutive months with no menstrual period. To avoid a scale score that reflected binge-purging type behaviors unequally (5 of 8 behaviors assessed), separate means for the binge-purging-type behaviors and restrictive-type behaviors were computed and averaged to form a DEB composite score. This measure was used in the earlier study (Stein & Corte, 2007). Results from that study showed behavioral scores from this measure correlated with behavioral frequencies measured with the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1992) with rs ranging from .51 to .88 in a previous study of clinically diagnosed women with EDs. Only the correlation for vomiting was outside of this range, r = .31.

Procedures

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan and all participants completed an informed consent prior to data collection. Because this study also included measures not reported here (mood and psychiatric symptom questionnaires, attention measures, and anthropometric measures) baseline data were collected in 4 sessions over a 1-month period of time. A health history and physical examination were also completed at baseline, 6 and 12 months to monitor changes in symptom severity and determine eligibility to continue with the protocol. All data were collected in individual sessions with only the data collector present in an office isolated from pedestrian traffic. To minimize the effects of experimenter demand on self-concept and ED measures, participants were informed that the study concerned how college women’s thoughts and feelings about themselves affect their health behaviors. During Session 1, participants completed the closed-ended self-schema measure, EDI, health behavior questionnaire, and then height and weight were measured. During Session 2, the open-ended self-schema measure was completed first to avoid priming effects followed by measures not reported here (mood and psychiatric symptom questionnaires). During Session 3, the information processing measures of the body-weight self-schema were completed. The adjectives were presented on a Power Macintosh computer which recorded participants’ Me or Not Me endorsements and RLT. Each adjective appeared individually at the center of the monitor screen for a maximum of 2000 ms. A 2000 ms interval was interpolated between the subject’s response and presentation of the next adjective. If the 2000 ms lapsed before an endorsement was made, both the endorsement and RLT variables for the item were considered missing. Participants responded by pushing one of two buttons on a computer mouse labeled Me and Not Me. The Me button was positioned in the subject’s dominant hand. To ensure that distractions did not interfere with information processing measures, signs reading “Quiet…..Data Collection in Process” were placed on the closed door prior to data collection. In Session 4, measures not reported here were completed (measures of attention, anthropometrics, health history and physical examination).

Follow-up data were collected in one session at 6 months and again at 12 months. At the 6-month follow-up, the health behaviors questionnaire and other measures not reported here (attention measures, anthropometrics, health history and physical examination) were completed. At the 12-month follow-up, the open-ended self-schema measure, closed-ended self-schema measure, health behaviors questionnaire, and other measures not reported here (attention measures, mood and psych symptoms questionnaires, and health history and physical examination) were completed. Participants were paid $132 for completing the 6 sessions ($7 after session 1, $25 after session 4, $25 after the 6-month follow-up, and $75 after the 12-month follow-up). At the completion of the study, participants were debriefed about the specific focus and aims of the study. During that session, the significance of the ED behavior was discussed with all participants in the DEB group and a written referral list for ED treatment was provided.

Data Analysis

Repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) and covariance were used to test the hypotheses that women engaging in subclinical levels of DEB would differ from controls in the number of positive and negative self-schemas, interrelatedness, and in the availability of a fat self-schema in memory. A series of regression analyses were used to test the hypothesis that the number of positive and negative self-schemas and interrelatedness predicts the availability of a fat body weight self-schema, which in turn predicts ED attitudes and behaviors concurrently and prospectively. Additional regression analyses were also completed to examine the role of positive and negative self-schemas and interrelatedness on the fat self-schema over time, and to rule out the competing hypothesis that self-concept properties are an outcome rather than a determinant of ED behaviors.

Results

No differences were found between the DEB group and controls in age (18.2 vs. 18.1 years) or race. Of the DEB group, 19.5% was minority (1.3% African American, 13% Asian, 1.3% Hispanic, and 3.9% mixed-race). In the control group, 26.8 % was minority (7.3% African American, 12.2% Asian, 0% Hispanic, and 7.3% mixed-race). The control group had a lower body mass index (BMI) than the DEB group (21.2 vs. 22.1, t[106] = 2.02, p < .05), but both groups were well within the normal range. Among women in the DEB group, ED attitudes (EDI scores) for Drive for Thinness and Body Dissatisfaction were in the clinical range (Garner, 1991) but the Bulimia scale score and the DEB were at a subthreshold level (Table 1).

Table 1.

Eating Disorder Inventory Means and Standard Deviations and Disordered Eating Behaviors at Baseline

| DEB Group (n = 77) |

Control Group (n = 41) |

|

|---|---|---|

| EDI Body Dissatisfaction | ||

| Mean (SD) | 18.7 (6.8) | 2.4 (3.8) |

| Range | 0–27 | 0–18 |

| EDI Drive for Thinness | ||

| Mean (SD) | 13.4 (5.4) | 0.2 (0.5) |

| Range | 0–21 | 0–3 |

| EDI Bulimia | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.9 (4.3) | 0.3 (0.9) |

| Range | 0–20 | 0–4 |

| % Restricting | 83.1 | -- |

| % Fasting | 57.7 | -- |

| % Amenorrheic × 3 months | 5.6 | -- |

| % Bingeing | 49.4 | -- |

| Mean (SD) # times per month* | 5.4 (8.6) | |

| % Vomiting | 32.5 | -- |

| Mean (SD) # times per month* | 8.56 (15.1) | |

| % taking Laxatives | 10.4 | -- |

| Mean (SD) # times per month* | 3.6 (2.1) | |

| % taking Diet Pills | 11.7 | -- |

| Mean (SD) # times per month* | 24.3 (16.7) | |

| % taking Diuretics | 2.6 | -- |

| Mean (SD) # times per month* | 3.5 (0.7) | |

| % Exercising > 1 hour per day | 33.8 | -- |

| Mean (SD) # times per month* | 3.8 (7.4) |

Note.

Only those engaging in behavior included in analysis.

Of the 77 women in the DEB group at baseline, 56 (73%) completed data at the 6-month follow-up and 55 (72%) completed data at the 12-month follow-up. Of the 41 women in the control group at baseline, 36 (88%) completed data at the 6-month follow-up and 39 (95%) completed data at the 12-month follow-up. Significantly more women in the DEB group dropped out compared to the control group (χ2 = 9.27, p = .002). Among women in the DEB group, no differences were found in age, race, baseline BMI, EDI scores, self-concept variables, or DEB between those who were retained and those who dropped out. Similar comparisons for the control group were not completed due to the small size of the dropout group.

Group Differences in the Number of Positive and Negative Self-Schemas and Interrelatedness

Number of Valenced Self-Schemas

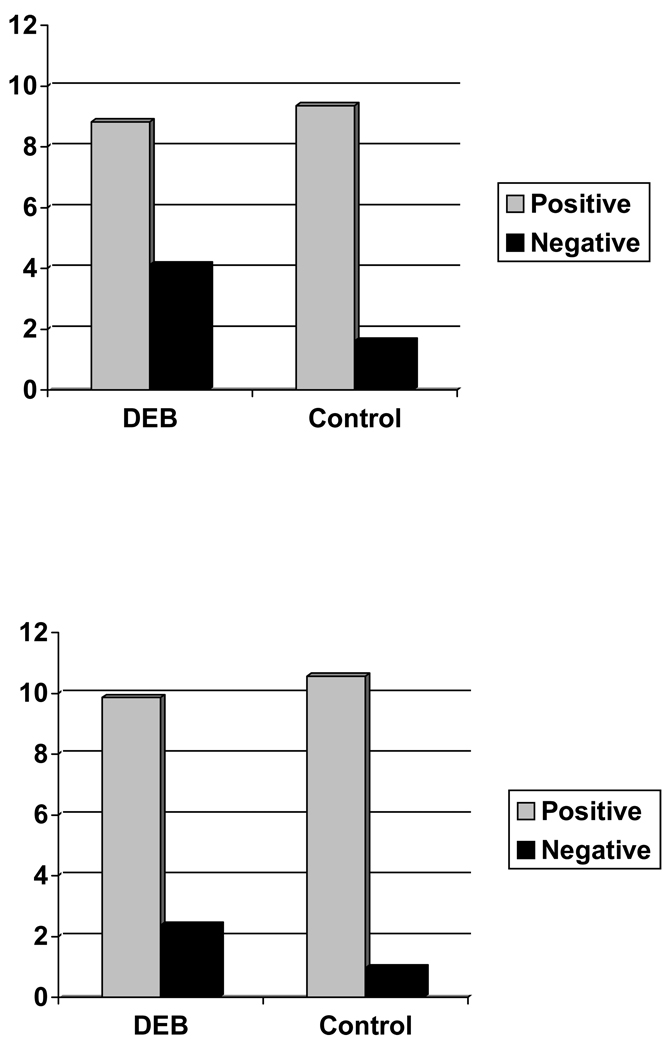

The number of valenced self-schemas by group adjusted for differences in BMI is shown in Figure 1. To address the hypothesis that women engaging in subclinical levels of ED behavior would have a self-concept characterized in part by fewer positive and more negative self-schemas compared to controls, an ANCOVA of the number of self-schemas classified by self-rated valence at baseline was completed. Because of group differences in BMI, this variable was used as a covariate. Results showed that the DEB group had significantly more negative self-schemas (adjusted M = 3.91) compared to controls (adjusted M = 1.19; p < .001), but contrary to predictions the DEB group did not have fewer significantly fewer positive self-schemas (adjusted M = 8.42) than controls (adjusted M = 9.37; p = .39).

Figure 1.

Organizational Properties of the Self-Concept by Group at Baseline (top) and 12-month Follow-up (bottom), Adjusting for Differences in BMI

Interrelatedness

To examine group differences in interrelatedness, an ANCOVA with BMI as a covariate was also used. Contrary to predictions, the degree of interrelatedness did not differ significantly by group (adjusted means: DEB = 0.19, control = 0.18; p = .44).

Availability of a Fat Self-Schema

To test the hypothesis that women in the DEB group would be more likely to define themselves as fat, analyses of covariance on the adjective endorsements and response latency times were completed. To control for possible group differences in general information processing, parallel responses to other words were used as a covariate in the analysis of each of the dependent variables. In addition, to control for objective differences in body weight between groups, BMI was also used as a covariate in these analyses.

Adjective endorsements

In the analysis of the proportion of fat adjectives endorsed as self-descriptive (i.e., Me ratings), both BMI (F = 11.34, p = .001) and control endorsed as self-descriptive (F = 6.67, p = .01) were significant covariates. The main effect for group was significant (F[1,109] = 52.50, p < .001). Pairwise comparisons showed that the DEB group endorsed as self-descriptive a significantly greater proportion of the fat words (adjusted M = 37.2%) relative to controls (adjusted M = 7.3%; p < .001).

Response latencies for adjective endorsements

To determine whether the groups differed according to their efficiency in processing the body-weight adjectives, the idiographic mean response latencies to the fat adjectives were examined. Because 66% (n = 27) of the women in the control group did not endorse even one fat word as self-descriptive, response latencies for Not Me judgments were used in the analysis. The RLT for the Not Me judgments of the control words was a significant covariate (F[1,107] = 34.25, p < .001), but BMI was not (p < 1). A significant main effect for group was also found (F[1,101] = 40.96, p < .001). Pairwise comparisons showed that the DEB group was significantly slower to make Not Me judgments for the fat adjectives (adjusted mean = 1.21 sec) compared to controls (adjusted mean = 0.96 sec).

Self-Concept as a Concurrent and Prospective Predictor of Disordered Eating Behaviors

A series of regression analyses were used to test the theoretical model that posits that organizational properties of the self-concept (few positive and many negative self-schemas and high interrelatedness) predict the fat self-schema score, which in turn predicts DEB concurrently and prospectively (6 and 12 months later). A composite measure of the two information-processing indicators of the fat self-schema (proportion of fat adjectives endorsed as Me and RLT for Not Me judgments of fat adjectives) was computed to reduce multicollinearity between these two variables (r = .61). The Z scores for these two variables were summed to compute the composite measure of the fat self-schema that was used in the regression analyses. Unadjusted group means and standard deviations, and correlations for all variables in the regression analyses are in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlations and Group Means and Standard Deviations for all Variables Used in Path Analyses

| Positive | Negative | IR | BMI | Fat SS | DEB Baseline | DEB 6 months |

DEB 12 months |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | −.04 | .03 | .05 | −.14 | −.08 | −.05 | −.13 | |

| Negative | .07 | −.01 | .49*** | .44*** | .36*** | .33** | ||

| IR | .07 | .08 | .12 | .08 | .08 | |||

| BMI | .35*** | .21* | .09 | .07 | ||||

| Fat SS | .65*** | .56*** | .53*** | |||||

| DEB Baseline | .78*** | .67*** | ||||||

| DEB 6 months | .70*** | |||||||

| DEB 12 months | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | ||||||||

| DEB | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.66 (5.78) | 3.90 (3.57) | 0.19 (0.10) | 22.15 (2.39) | 0.76 (1.73) | 1.26 (0.50) | 1.27 (0.46) | 1.29 (0.49) |

| Control | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 9.27 (4.85) | 1.27 (1.98) | 0.18 (0.12) | 21.25 (1.98) | −1.36 (0.62) | 0.10 (0.15) | 0.58 (0.15) | 0.61 (0.24) |

Notes. Positive = number of positive self-schemas; Negative = number of negative self-schemas; IR = interrelatedness; Fat SS = fat self-schema (Z) score; DEB = disordered eating behaviors composite score.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p < .001

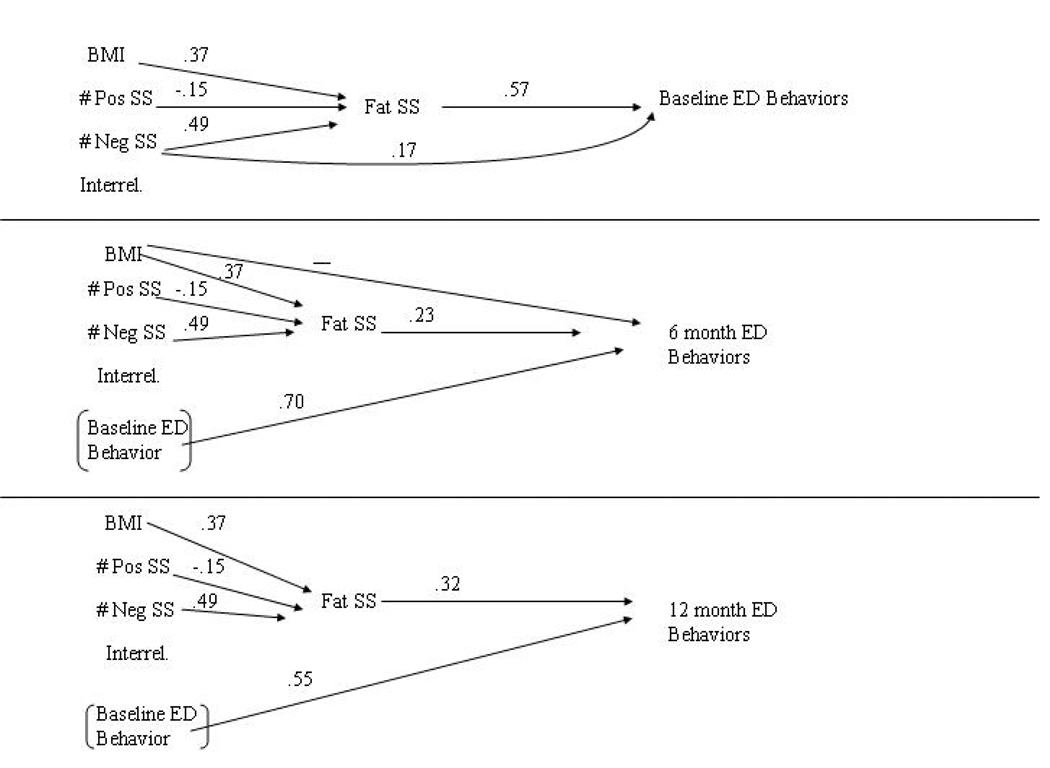

Predicting Concurrent Disordered Eating Behaviors

To predict DEB concurrently (at baseline), two regression analyses were completed. In the first analysis, the number of positive and negative self-schemas and interrelatedness were used to predict the fat self-schema score. The BMI was entered also as a control variable because of group differences in BMI. Although the groups did not differ in the number of positive self-schemas and interrelatedness at baseline, these variables were included because the variables are critical components of the theoretical model. The number of positive self-schemas negatively predicted the fat self-schema score (β = −.15, p = .06), and the number of negative self-schemas (β = 49, p < .001) and BMI (β = .37, p < .001) positively predicted the fat self-schema score. Interrelatedness, however, was not a significant predictor (β = .03, p = .71). In the second analysis, the four self-concept variables and BMI were used to predict DEB at baseline. The model was significant (F[5,101] = 16.26, p < .001) and accounted for 45% of the variance in DEB. Only the fat self-schema predicted DEB (β = .57, p < .001). Sobel tests showed that the fat self-schema partially mediated the effects of negative self-schemas (Z = 4.29, p < .001) on DEB, but did not mediate the effects of positive self-schemas on DEB (Z = 1.79, p = .07). In addition to its indirect effect through the fat self-schema, negative self-schemas also directly contributed to DEB (β = .17, p = .06; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graphic Depiction of Models Predicting Eating Disordered Behavior at Baseline, 6 Months, and 12 Months

Predicting Disordered Eating Behaviors 6 Months Later

The same analyses were used to predict DEB 6 months later controlling for baseline DEB (Figure 2). The model was significant (F(6,75) = 28.57, p < .001), and accounted for 70% of the variance in DEB. Baseline DEB was a strong predictor (β = .70, p < .001) of DEB 6 months later. However, it is important to note that the fat self-schema remained a significant predictor (β = .23, p = .016) even after controlling for baseline DEB. Sobel tests showed that the fat self-schema significantly mediated the effects of negative (but not positive) self-schemas on ED behavior 6 months later (Z = 1.91, p = .05). Also, BMI negatively predicted DEB 6 months later (β = −.16, p = .026) although it did not directly contribute to DEB in the first (concurrent) model.

Predicting Disordered Eating Behavior 12 Months Later

Finally, the same analyses were used to predict DEB 12 months later. The model was significant (F(6,75) = 16.54, p < .001) and accounted for 57% of the variance in DEB. Once again, baseline DEB was a strong predictor (β = .55, p < .001) of DEB 12 months later. However, the fat self-schema continued to be a significant predictor of DEB 12 months later (β = .32, p = .013) even after controlling for baseline DEB. Sobel tests, however, showed that the fat self-schema did not mediate the effects of positive or negative self-schemas on ED behavior significantly 12 months later, and BMI was no longer a significant predictor (Figure 2).

Self-Concept Variables at Baseline Predict Increase in Fat Self-Schema 12 Months Later

To determine whether the underlying self-structure variables (positive and negative self-schemas and interrelatedness) strengthen the fat self-schema over time, regression analyses were completed using baseline self-structure variables to predict the fat self-schema (closed-ended measure) score 12 months later. First, each component of the fat-self schema--self-descriptiveness of fat and the importance of fat--was predicted separately. The corresponding baseline fat self-schema score component and BMI were also included as predictors. Regression analyses showed that the number of positive self-schemas predicted the self-descriptiveness of fat, whereas the number of negative self-schemas predicted the importance of fat to the self-definition. More specifically, the number of positive self-schemas at baseline (β = −.20, p = .05) negatively predicted the self-descriptiveness score for fat 1 year later (controlling for baseline self-descriptiveness), whereas the number of negative self-schemas at baseline (β = .18, p = .05) positively predicted the importance rating for fat 1 year later (controlling for baseline importance rating). When both components of the fat self-schema (mean of both the descriptiveness and importance ratings) were combined, results showed that the number of negative self-schemas at baseline (β = .12, p = .037) significantly predicted the fat self-schema score 12 months later, controlling for the baseline fat self-schema score (β = .80, p < .001; F[5,87] = 55.4, p < .001, R2 = 76).

Do Disordered Eating Behaviors Predict Self-Concept Disturbances?

To rule out the possibility that DEB influence the organizational properties of the self-concept, regression models were completed using baseline DEB to predict the number of positive self-schemas, number of negative self-schemas, and interrelatedness at 12 months. In each analysis, the related baseline self-concept variable was included as a predictor. Results showed that baseline DEB did not predict any of the self-concept variables at 12 months (ps ≥ 15).

Discussion

Results of this study provide new support for the identity impairment model that disturbances in the overall array of self-cognitions contribute to the development of DEB and perhaps to the onset of diagnosable levels of EDs. Consistent with the findings from our previous cross sectional study of women with clinically diagnosed AN and BN, the results of this study show that a self-concept comprised of few positive and many negative self-schemas predicts the availability of a fat self-schema, which in turn predicts increases of DEB in college women as they transition from their freshman to sophomore year. In addition, results showing a relationship between the number of valenced self-schemas and the strengthening of the fat self-schema suggest a plausible mechanism through which the cognitive vulnerabilities are structuralized into an enduring pattern of behavior.

Results of this study convincingly show that the fat self-schema plays an important role in the escalation of DEB over time. In this sample of women who have no history of treatment for an ED, availability of a fat self-schema in the freshman year predicted increases in level of DEB 6 and 12 months later. This suggests that defining oneself as fat is an important contributor to the development of ED behavior, and is not related to treatment or treatment-seeking. In addition to our earlier study (Stein & Corte, 2007), the findings of this study are consistent with a large collection of other studies that have shown a link between body image disturbances and DEB (Taylor et al., 2006) and in fact raise a question about whether a fat self-definition may be better viewed as an early symptom of the ED rather than an etiological factor. Contrary to the popular view that conceptions of the self as fat are normative, results of both studies suggest that only a subset of young adult women have an elaborated and stable cognitive structure of the self as fat and those who do demonstrate patterns of DEB behavior.

A critical question that has surfaced in the ED literature has to do with what causes some women to focus on body weight as an important source of self-definition. Results of this study show that the number of valenced self-schemas predict the availability of a fat self-schema at baseline and contribute to the strengthening of this self-cognition over time. The number of positive schemas influenced the availability and strengthening of the fat self-schema but showed no direct or indirect effects on the level of DEB. Fewer positive self-schemas predicted the availability of a fat self-schema at baseline and strengthened the self-descriptiveness of fat over time. The number of negative self-schemas had an indirect effect on increases in DEB and this effect was mediated by the fat self-schema. Having many negative self-schemas predicted increases in the level of DEB at 6 and 12 months. In addition, the number of negative self-schemas positively predicted increases in the importance of fat to one’s self-definition over the freshman to sophomore year. These findings suggest that although positive and negative self-schemas function somewhat differently, together they increase vulnerability to patterns of ED not only at the clinical but also subclinical levels of severity.

The fact that the two groups did not differ in the number of positive self-schemas and the level of interrelatedness was unexpected, although the differences in the observed means were in the expected direction. One explanation is that the DEB group was heterogeneous in terms of the severity of DEB with some members of the group involved in transient experimentation with the behaviors and others engaged in more stable and serious patterns moving toward a diagnosable ED. Hence, the greater variability in availability of positive self-schemas and interrelatedness among these subsets may have compromised the ability to detect the expected group differences.. Additional research is needed to determine whether meaningful ED behavior trajectories can be identified and whether differences in the organizational properties of the self-concept exist within these subgroups.

Although the longitudinal design of the study is an important step in teasing out the causal role of self-concept properties in the etiology of the EDs, longer follow-up is needed to determine whether self-concept properties predict formation of diagnosable EDs. As mentioned, the subclinical sample addressed in this study is likely to be highly heterogeneous with only a small proportion progressing to a full AN or BN syndrome. Hence, additional longitudinal work is needed to clarify the causal link between the self-concept and consolidation of behaviors into severe levels of the disorders. In addition, more longitudinal research is needed to investigate more fully the causal relationship between the valenced number and organization of the total array of self-schemas and the formation of the fat self-schema. In this study, indicators of the fat self-schema were measured simultaneously with properties of the self-schemas and hence, causality cannot be established firmly. A longitudinal study of school age children is necessary to fully establish the developmental trajectory of these components of the self-concept.

Despite the limitations, the results of this study provide important new data supporting the long held clinical conviction that properties of the overall collection of self-cognitions are a fundamental vulnerability that contribute to formation of DEB. These findings are consistent with the view that while body image disturbances and cognitions of the self as fat play a proximal role, the array of positive and negative self-schemas are a basic and fundamental factor in escalating patterns of DEB over time. These findings suggest an important new focus for psychiatric nurses and other mental health professionals involved in the prevention and treatment of the EDs. Rather than the traditional focus on body image, these findings suggest that interventions designed to prevent behavioral consolidation or promote long-term recovery and cure must focus on the total array of self-schemas available in memory, striving to increase the positive conceptions of the self while diminishing the accessibility and importance of the negative selves.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research #NIH, R29 NR03457. Thank you to Linda Nyquist for her assistance with data analyses and Jennifer Sandoz, Elizabeth Brough, and Judy Sargent for their assistance with data collection activities.

Footnotes

These data were presented at the Academy for Eating Disorders 9th International Conference on Eating Disorders, New York, NY.

Contributor Information

Karen Farchaus Stein, School of Nursing, The University of Michigan.

Colleen Corte, College of Nursing, University of Illinois at Chicago.

References

- Clemmey PA, Nicassio PM. Illness self-schemas in depressed and nondepressed rheumatoid arthritis patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;20(3):273–290. doi: 10.1023/a:1025556811858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Markus HR. Self-schemas, possible selves and competent performance. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1994;86:423–438. [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski JM, Andersen BL. Schemas, sexuality, and romantic attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1364–1379. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon TM, Baumeister RF. Escaping the self: The moderating effects of cognitive complexity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1991;17:363–368. [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. Self-complexity and its relation to development, symptomatology, and self-perception during adolescence. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 1994;24:173–182. doi: 10.1007/BF02353194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froming WJ, Nasby W, McManus J. Prosocial self-schemas, self-awareness, and children’s prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(3):766–777. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.3.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner D. Eating Disorders Inventory-2 professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1983;2:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Green JD, Sedikides C. When do self-schemas shape social perception? The role of descriptive ambiguity. Motivation and Emotion. 2001;25:67–83. [Google Scholar]

- young adult alcohol and tobacco use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 114:612–626. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzierski D. Self-schemata and exercise. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1988;9:45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kendzierski D, Costello MC. Healthy eating self-schema and nutrition behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004;34(12):2437–2451. [Google Scholar]

- Kendzierski D, Sheffield A. Self-schema and attributions for an exercise lapse. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2000;22:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kendzierski D, Whitaker D. The role of self-schema in linking intentions with behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Linville P. Self-complexity as a cognitive buffer against stress-related illness and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:663–676. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips H. Through the lens of mathematical/scientific self-schemas: Images of students’ current and possible selves. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1995;25:1671–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Markus H. Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1977;35:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Hamill R, Sentis K. Thinking fat: Self-schemas for body weight and the processing of weight relevant information. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1987;17:50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Smith J, Moreland R. Role of the self-concept in the perception of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49:1494–1512. [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Wurf E. The dynamic self-concept: A social psychological perspective. In: Rosenweig MR, Porter LW, editors. Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 38. 1987. pp. 299–337. [Google Scholar]

- Niedenthal PM, Beike DR. Interrelated and isolated self-concepts. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1997;1:106–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0102_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak A, Vallacher RR, Tesser A, Borkowski W. Society of self: The emergence of collective properties in self-structure. Psychological Review. 2000;107:39–61. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.107.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TB, Kuiper NA, Kirker W. Self-reference and encoding of personal information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1977;35:677–688. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.35.9.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Orbell S. Self-schemas and the theory of planned behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2000;30(4):533–550. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, I: History, rationale, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KF. The organizational properties of the self-concept and instability of affect. Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18:405–415. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KF. The self-schema model: A theoretical approach to the self-concept in eating disorders. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1996;10:96–109. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(96)80072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KF, Corte C. Reconceptualizing causative factors and intervention strategies in the eating disorders: A shift from body image to self-concept impairments. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2003;17:57–66. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2003.50000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KF, Corte C. Identity impairment and the eating disorders: Content and organization of the self-concept in women with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review. 2007;15:58–69. doi: 10.1002/erv.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KF, Hedger KM. Body-weight and shape self-cognitions, emotional distress, and disordered eating in middle adolescent girls. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1997;11:264–275. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(97)80017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore R, Dohm F, Pike K, Wilfley D, Fairburn C. Abuse, bullying, and discrimination as risk factors for binge eating disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1902–1907. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CB, Bryson S, Luce KH, Cunning D, Doyle AC, Abascal LB, et al. Prevention of eating disorders in at-risk college-age women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:881–888. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear RW, Pratz O. Test retest reliability for the eating disorder inventory. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1987;6:767–769. [Google Scholar]

- Westen D, Heim K. Disturbances of the self and identity in personality disorders. In: Leary M, Tangney J, editors. Handbook of self and identity. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 643–664. [Google Scholar]