Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD), the most common inherited hematologic disorder in the United States and the most common single gene disorder in the world, causes substantial morbidity and mortality. The major pathobiologic processes that underlie SCD include vaso-occlusion, inflammation, procoagulant processes, hemolysis, and altered vascular reactivity. The present study examined the vasoactive response to α-adrenergic activation in a murine model of SCD. Isolated aortas from sickle mice as compared with wild-type mice exhibit heightened contractions to norepinephrine and phenylephrine; such responses were completely blocked by an α1-receptor antagonist, prazosin. Aortas from either group exhibited comparable contractile responses to potassium chloride and the thromboxane agonist U46619 and no contractile response to an α2-adrenergic receptor agonist, UK14304. We conclude that there is an exaggerated vasoconstrictive response to α1-receptor agonists in SCD. Because sickle crisis is induced by diverse forms of stress, the latter attended by increased adrenergic activity, our findings may be relevant to the occurrence of sickle crisis. We also suggest that such heightened reactivity may contribute to vaso-occlusive processes that underlie ischemic injury in SCD. Finally, our findings urge caution in the use of phenylephrine in patients with SCD.

Keywords: sickle cell disease, vascular reactivity, vasoconstriction, α1-adrenergic receptors, phenylephrine

INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD), a homozygous condition characterized by the presence of the mutant human sickle hemoglobin, is the most common inherited hematologic disorder in the United States and the most common single gene disorder in the world.1 Afflicting predominantly African Americans and other ethnic minorities, and occurring in 1 in every 500 African American births, SCD causes substantial morbidity and a shortened life span; the health care costs are appreciable, involving more than 75,000 hospitalizations over a 4-year period and accruing an approximate cost of a half of a billion dollars.1

SCD leads to chronic injury to major organs and tissues and imposes acute “crisis” episodes in which the dominant symptom is pain.2-5 The major pathogenetic pathways that contribute to chronic tissue injury and acute pain syndromes include red blood cell (RBC) sickling, vaso-occlusion, and attendant impairment in tissue perfusion; ischemia–reperfusion injury; inflammatory pathways; procoagulant processes; intravascular hemolysis; and altered vascular reactivity.2-5 Any one of these processes may serve to initiate and foster another, and through numerous such interactions, a perturbation beginning in one can culminate in the recruitment of all: for example, increased vasoconstriction, by its rheological effects, can incite RBC sickling, and, through these and other effects, can alter hemostasis and thereby promote thrombosis; systemic inflammation, a characteristic feature of SCD, activates the endothelium, and alters vascular reactivity; procoagulant processes not only are intrinsically inflammatory in nature but also can lead to the elaboration of vasoconstricting species; intravascular hemolysis can lead to the siphoning of nitric oxide from the vasculature by extracellular hemoglobin, thereby provoking vasoconstriction.2-5

In view of the recognition of the contribution of altered vascular reactivity to the complications of SCD, the present study examined vascular responses in SCD to α-adrenergic activation. This analysis was undertaken for the following reasons. First, comparatively little information exists in the literature regarding this issue. Second, episodes of acute sickle crisis are usually precipitated by diverse conditions (eg, changes in temperature, exercise, systemic illness, viral syndromes and other infections, emotional stress, menses) that are all characterized by “stress,” the latter leading to the recruitment of the adrenergic system.2-5 Third, evidence is emerging that autonomic dysfunction occurs in SCD wherein sympathetic activity is increased relative to parasympathetic activity.6-10 Using a well-characterized murine model of SCD,11-14 we employed an ex vivo approach so as to directly examine the intrinsic vascular reactivity to α-adrenergic activation without the confounding effects originating from other processes occurring in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Mayo Clinic and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines. The murine model of SCD employed in this study, and characterized in our prior studies, is homozygous for a murine β-globin deletion, carries 2 transgenes (αHβS and αHβS-Antilles), and is on a C57Bl6 background11-14; in each protocol, mice were age matched and consisted of comparable numbers of male and female mice. Experiments were performed on 3-mm-long aortic rings from mice that had been anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg intraperitoneal) as detailed in our previous studies.11 Rings were studied in modified Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate solution (control solution) of the following composition (in millimolar): 118.3 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, 0.026 calcium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 11.1 glucose. Each ring was connected to an isometric force transducer and suspended in an organ chamber filled with 25 mL of control solution (37°C; pH 7.4) bubbled with a 94% O2–6% CO2 gas mixture.

α1-Adrenergic receptor messenger RNA (mRNA) expression was determined by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction.14 Western analysis for protein expression was undertaken using antibodies for the pan–α1-adrenergic receptor (Sigma, catalog #A270) and for the α1D subtype (Abcam, catalog #ab84402); these antibodies were not among those included in recent analysis of commercially available antibodies for the α1-adrenergic receptor and its subtypes, and which concluded that these antibodies are nonspecific and do not detect appropriately sized bands on Western analyses.15

Statistics

Values are expressed as means ± standard errors of the mean; n, the number of mice used, is indicated for each experiment. For comparison of the concentration-dependent contractile responses, analysis of variance and the Bonferroni test were used. Differences were considered significant for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

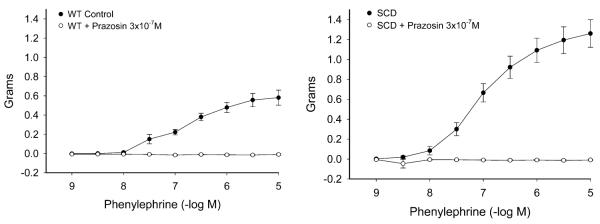

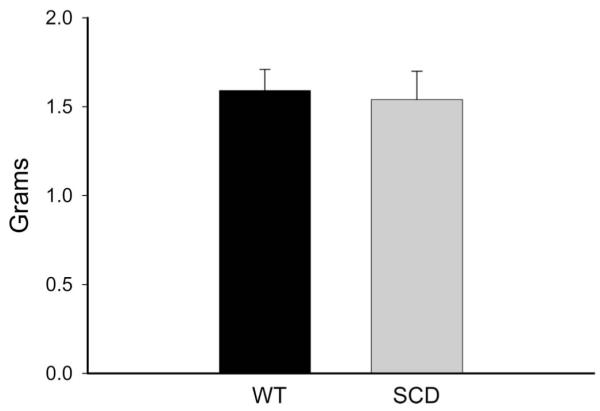

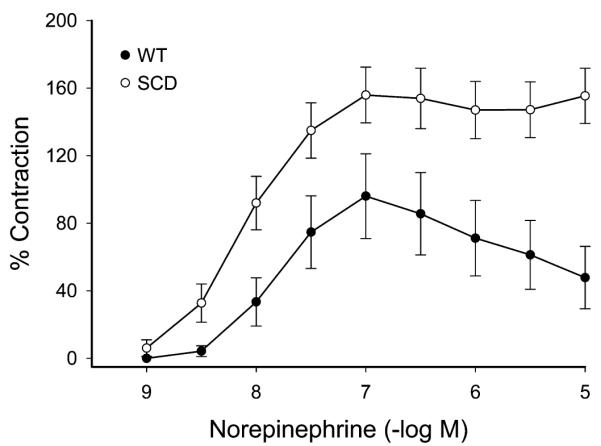

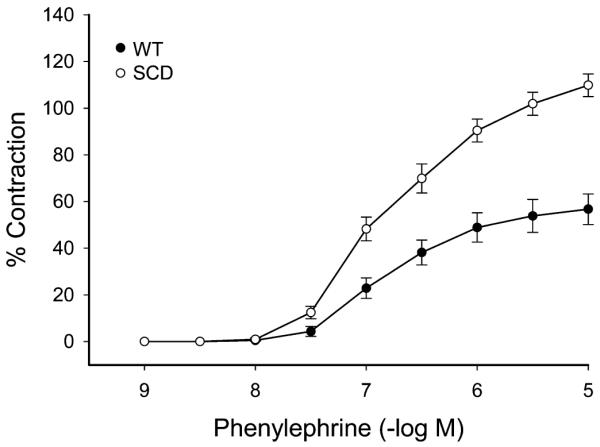

The maximum contractile response to 80 mM of KCl was not different in wild-type (WT) and sickle mice (Fig. 1). The contractile response to norepinephrine, however, was markedly different with an exaggerated contractile response in sickle mice as compared with WT mice (Fig. 2). This augmented contractile response was not only seen for norepinephrine but also with the selective α1-adrenergic agonist phenylephrine (Fig. 3). The contractile response to phenylephrine in both WT and sickle mice was completely blocked by the α1-adrenergic receptor blocker, prazosin (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 1.

Contractions to potassium chloride (KCl, 80 mmol/L) in aortas of WT mice and mice with SCD. Results are mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 6; P = NS).

FIGURE 2.

Concentration-dependent contractions to norepinephrine in aortas of WT mice and mice with SCD. Results are mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 5), and contractions are expressed as percent of contractions to 80 mmol/L KCl. Contractions to norepinephrine were significantly enhanced in mice with SCD (P < 0.05, analysis of variance).

FIGURE 3.

Concentration-dependent contractions to phenylephrine in aortas of WT mice and mice with SCD. Results are mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 4), and contractions are expressed as percent of contractions to 80 mmol/L KCl. Contractions to phenylephrine were significantly enhanced in mice with SCD (P *lt; 0.05, analysis of variance).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of blockade of α1-adrenergic receptors on contractions to phenylephrine in aortas of WT mice and mice with SCD. Results are mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 4). Contractions to phenylephrine were abolished in the presence of prazosin (3 × 10−7 M) in both WT mice and mice with SCD (P < 0.05; analysis of variance).

In contrast to these findings, we failed to observe any contractile responses to the α2-adrenergic receptor agonist UK14304 in aortic rings from either WT or sickle mice (data not shown). We also examined the effect of another vasoconstrictive agent, U46619, a selective synthetic analog of thromboxane A2. As shown in Table 1, contractile responses to U46619 were not different in aortic rings from WT and sickle mice, nor was there a differential effect in the presence of prazosin. These findings thus establish the selectivity of enhanced reactivity of the aorta from mice with SCD to activation of α1-adrenergic receptors.

TABLE 1.

Contractions to U46619 in Aortas of WT and SCD Mice

| Control |

Prazosin, 3 × 10−7 M |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −log EC50 | Max grams | −log EC50 | Max grams | |

| WT | 8.15 ± 0.10 (6) | 1.94 ± 0.20 (6) | 7.84 ± 0.04 (6) | 2.68 ± 0.07 (6) |

| SCD | 8.30 ± 0.03 (6) | 2.56 ± 0.21 (6) | 8.02 ± 0.03 (6) | 2.40 ± 0.26 (6) |

The number of aortic rings is in parentheses. EC50, half-maximal effective concentration.

In the aortas from control and sickle mice, there were no significant differences in mRNA expression of each of the following subtypes (standardized for 18S ribosomal RNA expression): α1A-adrenergic receptor [2.9 ± 0.3 vs. 3.6 ± 0.5, n = 10 and n = 8 in this and subsequent real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction measurements, P = not significant (NS)], α1B-adrenergic receptor (1.5 ± 0.1 vs. 1.9 ± 0.2, P = NS), and α1D-adrenergic receptor (1.2 ± 0.1 vs. 1.6 ± 0.2, P = NS). Western analyses for expression of the pan–α1-adrenergic receptor or the α1D-adrenergic receptor subtype failed to locate a band consistent with the known molecular weights of these proteins (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In SCD it is well recognized that vasorelaxant responses are impaired and such impairment can arise from endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent processes.2-5 Less well studied is the nature of vascular responses to vasoconstrictive agonists, and in this regard, and to the best of our knowledge, the findings in this brief communication provide the first demonstration of a heightened contractile response to α1-adrenergic activation. Given the propensity in SCD to impaired tissue perfusion occasioned by RBC sickling and stasis, and procoagulant processes, this enhanced sensitivity of the vasculature to α-adrenergic activation may thus be considered as another pathobiologic process that predisposes to the vaso-occlusive nature of SCD. Additionally, our present findings, in conjunction with prior observations, demonstrate the existence in SCD of dual and complementary defects in the behavior of the vasculature germane to settings in which adaptive vascular responses are needed to maintain adequate tissue perfusion: The vasculature in SCD exhibits not only an impaired vasorelaxant response but also a markedly exaggerated vasoconstrictive response, at least to activation of α1-adrenergic receptors.

Sickle crisis is precipitated by diverse settings all of which are characterized by some form of stress. Such stress would be accompanied by increased sympathetic activity and attendant activation of α-adrenergic receptors. To the extent that heightened, α1-adrenergic vasoconstriction would be an unfavorable vascular response in such circumstances, and may predispose to the sickling process, we speculate that α1-adrenergic vasoconstriction may represent a pathway common to diverse stimuli that provoke sickle crisis. Interestingly, adrenergic-driven vasoconstriction may synergize with procoagulant processes in SCD; for example, increased adhesiveness of sickle RBCs to the endothelium may reflect the increased expression of the Lutheran glycoprotein present in sickle RBCs, and such adhesiveness is fostered by adrenergic agonists.16

We have previously suggested that SCD may be viewed as a disease attended by vascular instability because there is concomitant upregulation of vasorelaxant and vasoconstrictor species; an impairment in any one of these vasorelaxant systems leaves vasoconstrictor systems relatively unopposed, thereby incurring a vasoconstrictive response.2,11 Indeed, after an ischemic insult, renal vascular resistances are markedly increased and renal blood flow strikingly reduced in murine SCD.14 A similar phenomenon is observed after hypoxia–reoxygenation in murine SCD, and this has been shown to reflect increased expression of endothelin-1,17 a vasoconstricting peptide incriminated in decreased tissue perfusion in SCD.18 However, such expression of endothelin-1 may not explain the enhanced renal vasoconstrictive response after renal ischemic injury;14 it is thus possible that α1-adrenergic mechanisms may be involved in such settings. Interestingly, endothelin-1 is induced in some vascular beds by α1-adrenergic pathways,19 and α1-adrenergic activity may condition the response to endothelin-1, thereby raising the possibility that there may be cross talk between α1-adrenergic mechanisms and endothelin-1 observed in SCD.

The augmented vascular responses we observed in SCD cannot be explained by differences in receptor expression, at least as assessed by mRNA expression. Of interest to this phenomenon, and deserving of study, is the contribution/involvement of the following: the endothelium, cellular calcium fluxes, the state of phosphorylation of myosin light chain and phosphorylation of myosin phosphatase target protein-1, and receptor-downregulating mechanisms including G-protein–coupled receptor kinase and arrestins.

We also suggest that at least from 2 considerations, our findings are relevant to priapism, the latter occurring in SCD with a prevalence of 30%–40%.20 First, local administration of phenylephrine and other α-adrenergic agents often prove efficacious in aborting priapism that fails to respond to conservative measures20; we suggest that such efficacy reflects the enhanced α1-adrenergic vasoconstriction that exists in the vasculature in SCD, thereby leading to decreased penile blood flow. Second, the use of antihypertensive agents in SCD, especially prazosin, increases the risk for priapism in SCD21; in our studies, prazosin completely blocked the contractile response to phenylephrine and norepinephrine.

That an augmented vasoconstrictive response to α1-adrenergic agonists such as phenylephrine occurs in SCD raises a substantial concern regarding the over-the-counter use of phenylephrine and other α-adrenergic agonists in this patient population. Indeed, accelerated hypertension and subarachnoid hemorrhage have been described in SCD after the use of phenylephrine in priapism,22 and acute myocardial infarction in SCD has been linked to the use of pseudoephedrine.23 The over-the-counter use of phenylephrine and other α-adrenergic agonists is an issue of ongoing debate in general, and we suggest that such discussion is of particular relevance and timeliness in SCD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the technical expertise of Ms Leslie Smith, Mr Anthony Croatt, Mr Allan Ackerman, and the secretarial expertise of Ms Tammy Engel.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health grant HL55552.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health [Accessed February 16, 2010];Sickle cell anemia: who is at risk? Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/Sca/SCA_WhoIsAtRisk.html.

- 2.Nath KA, Katusic ZS, Gladwin MT. The perfusion paradox and vascular instability in sickle cell disease. Microcirculation. 2004;11:179–193. doi: 10.1080/10739680490278592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belcher JD, Mahaseth H, Welch TE, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 is a modulator of inflammation and vaso-occlusion in transgenic sickle mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:808–816. doi: 10.1172/JCI26857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris CR. Mechanisms of vasculopathy in sickle cell disease and thalassemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008:177–185. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2008.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hebbel RP, Vercellotti G, Nath KA. A systems biology consideration of the vasculopathy of sickle cell anemia: the need for multi-modality chemo-prophylaxis. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9:271–292. doi: 10.2174/1871529x10909040271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero Mestre JC, Hernandez A, Agramonte O, et al. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in sickle cell anemia: a possible risk factor for sudden death? Clin Auton Res. 1997;7:121–125. doi: 10.1007/BF02308838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sangkatumvong S, Coates TD, Khoo MC. Abnormal autonomic cardiac response to transient hypoxia in sickle cell anemia. Physiol Meas. 2008;29:655–668. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/29/5/010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sangkatumvong S, Khoo MC, Coates TD. Abnormal cardiac autonomic control in sickle cell disease following transient hypoxia. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2008;2008:1996–1999. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4649581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connes P, Barthelemy JC. Abnormal autonomic cardiac response to transient hypoxia in sickle cell anemia. Physiol Meas. 2008;29:L1–L2. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/29/9/L01. comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexy T, Sangkatumvong S, Connes P, et al. Sickle cell disease: selected aspects of pathophysiology. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2010;44:155–166. doi: 10.3233/CH-2010-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nath KA, Shah V, Haggard JJ, et al. Mechanisms of vascular instability in a transgenic mouse model of sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1949–R1955. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nath KA, Grande JP, Croatt AJ, et al. Transgenic sickle mice are markedly sensitive to renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:963–972. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62318-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juncos JP, Grande JP, Murali N, et al. Anomalous renal effects of tin protoporphyrin in a murine model of sickle cell disease. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:21–31. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juncos JP, Grande JP, Croatt AJ, et al. Early and prominent alterations in hemodynamics, signaling, and gene expression following renal ischemia in sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F892–F899. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00631.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen BC, Swigart PM, Simpson PC. Ten commercial antibodies for alpha-1-adrenergic receptor subtypes are nonspecific. Naunyn Schmiede-bergs Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:409–412. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0368-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eyler CE, Telen MJ. The Lutheran glycoprotein: a multifunctional adhesion receptor. Transfusion. 2006;46:668–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabaa N, de Franceschi L, Bonnin P, et al. Endothelin receptor antagonism prevents hypoxia-induced mortality and morbidity in a mouse model of sickle-cell disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1924–1933. doi: 10.1172/JCI33308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelan M, Perrine SP, Brauer M, et al. Sickle erythrocytes, after sickling, regulate the expression of the endothelin-1 gene and protein in human endothelial cells in culture. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1145–1151. doi: 10.1172/JCI118102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi O, Kaneshiro T, Saitoh S, et al. Regulation of coronary vascular tone via redox modulation in the alpha1-adrenergic-angiotensin-endothelin axis of the myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H226–H232. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00480.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers ZR. Priapism in sickle cell disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2005;19:917–928. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banos JE, Bosch F, Farre M. Drug-induced priapism. Its aetiology, incidence and treatment. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1989;4:46–58. doi: 10.1007/BF03259902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davila HH, Parker J, Webster JC, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage as complication of phenylephrine injection for the treatment of ischemic priapism in a sickle cell disease patient. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1025–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Assanasen C, Quinton RA, Buchanan GR. Acute myocardial infarction in sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:978–981. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200312000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]