Abstract

By 2015, approximately half of adults with HIV in the United States will be 50 and older. The demographic changes in this population due to successful treatment represent a unique challenge, not only in assisting these individuals to cope with their illness, but also in helping them to age successfully with this disease. Religious involvement and spirituality have been observed to promote successful aging in the general population and help those with HIV cope with their disease, yet little is known about how these resources may affect aging with HIV. Also, inherent barriers such as HIV stigma and ageism may prevent people from benefitting from religious and spiritual sources of solace as they age with HIV. In this paper, we present a model of barriers to successful aging with HIV, along with a discussion of how spirituality and religiousness may help people overcome these barriers. From this synthesis, implications for practice and research to improve the quality of life of this aging population are provided.

Keywords: HIV, aging, spirituality, religion, stigma, coping, successful aging

Introduction

Thanks largely to the effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), people with HIV are aging.1,2 In 2005 in the United States, those 50 and older comprised 15% of all new HIV/AIDS cases, 24% of existing HIV cases, 29% of existing AIDS cases, and 35% of all HIV/AIDS-related deaths.3 By 2015, adults 50 and older will make up half of the HIV population in the United States; this number is expected to continue to grow because of the aging of younger cohorts with HIV as well as new infections among persons over 50.4

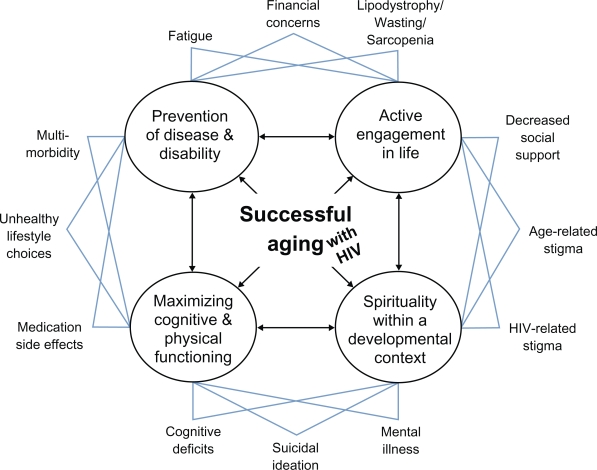

With this upward shift in the age of people living with HIV, it is important to consider ways to promote successful aging in this growing population. Building upon the work of Rowe and Kahn,5 Crowther and colleagues proposed four components of successful aging: 1) active engagement in life; 2) maximizing cognitive and physical functioning; 3) minimizing disability and disease progression; and 4) positive spirituality within a developmental context.5,6 It is proposed that all of these components work together to promote successful aging; if one area is neglected, then the other components are negatively affected, ultimately reducing one’s ability to age successfully. This model’s inclusion of spirituality parallels Pargament’s thematic switch from a biopsychosocial model to a biopsychosociospiritual model in understanding holistic therapeutic change.7,8

The purpose of this article is to summarize knowledge of spirituality as it is used to confront many of the barriers associated with successful aging with HIV. For this review, a model of successful aging with HIV is presented as a guide. A particular focus on spiritual benefits of coping will be provided during this review and in the implications for clinical practice and research. In discussing spirituality and religion, these two concepts are related but sometimes mutually exclusive. In this article, spirituality refers to “a person’s attempt to make sense of his world beyond the tangible and temporal. It strives to connect the individual with the transcendent and transpersonal elements of human existence. It might, but need not, include religion”.9 While religion may contribute to spirituality, it refers to an outward expression of beliefs as exhibited by behaviors, practices, and rituals which focus on a core system of doctrines, morals, and norms.9,10

Barriers to successful aging with HIV

Using the four components of successful aging with HIV mentioned above,5,6 barriers to each of these components are identified in the model in Figure 1. Although not exhaustive, these represent major barriers that have been articulated in the HIV and aging literature.2,4,11,12 Underlying this model are three assumptions. First, the four components necessary for successful aging in the general population also apply to those aging with a chronic disease such as HIV. Second, this model assumes that barriers to each of these components act as stressors, activating the physical, cognitive, social, and spiritual resources of successful aging available to the individual, in accordance with Folkman and Lazarus’s Stress Process Model.13 And third, all of these barriers are dynamic and interrelated, just as are the four components of successful aging. For example, age-related stigma and HIV-related stigma, although independent concepts themselves are also intertwined, in that older adults with HIV may be experiencing a combination of the two.

Figure 1.

Barriers to and components of successful aging with HIV.

Starting in the left hand corner of the model in Figure 1 and going clockwise, medication side effects from HAART (eg, diabetes, high cholesterol, heart disease); unhealthy lifestyle choices (eg, smoking, substance abuse); and increased multi-morbidity with HIV compromise the components of maintaining and maximizing cognitive and physical functioning and the prevention of disease and disability.2,14 Fatigue due to medication side effects; not possessing financial means to pay for medications and other self-care needs; and lipodystrophy and decreased muscle mass (eg, wasting, sarcopenia) compromise the components of prevention of disease and disability and active engagement in life. For example, lipodystrophy in more pronounced cases can result in severe loss of subcutaneous fat in the face producing profound disfiguration, which may reduce one’s inclination to socialize and actively engage in life.

Decreased social support (and increased social isolation), age-related stigma, and HIV-related stigma compromise the components of active engagement in life and spirituality within a developmental context. Studies show that 71% of older adults with HIV live alone and few (15%) reported living with a partner or spouse.15 Many older adults with HIV consider emotional and instrumental support from their social networks is either unavailable or inadequate.16,17 Decreased social support is closely tied to HIV stigma. HIV stigma can intensify other types of stigmas faced by many older adults, such as ageism, sexism, and racism. This may involve rejection, stereotyping, fear of contagion, violations of confidentiality, and protective silence (ie, concealing one’s HIV status to avoid negative reactions from others).18 Thus, many older adults with HIV withdraw socially due to HIV stigma,19,20 further decreasing active engagement in life. Stigma also serve to challenge successful aging with HIV with regard to spirituality. Cotton and colleagues reported that 25% of people with HIV/AIDS are alienated from their place of worship because of HIV stigma, and 10% changed congregations because of their HIV status,21 which can also contribute to poorer active engagement in life. Findings are similar among older adults with HIV, with 15% reporting attending services less frequently following their HIV diagnosis. Furthermore, less than half of these older adults disclose their HIV status to their congregations.22

Finally, mental illness (often depression and anxiety), suicidal ideation, and cognitive deficits compromise the successful aging components of “spirituality within a developmental context” and “maximizing cognitive and physical functioning”. These barriers have a greater prevalence in adults with HIV.23–25 In a large sample (N = 1,478) of adults with HIV, approximately 40% were found to be depressed and approximately 20% were found to have an anxiety disorder.14 Grov and colleagues found similar rates of major depression among older adults with HIV (39%), which was strongly related to HIV stigma and loneliness.26 In one study of 113 older adults (>45 years) with HIV/AIDS, 27% experienced suicidal ideation within the past week.27 With regard to cognitive functioning among older adults with HIV, the evidence to date is mixed; however, there are strong indications of neuropsychological impairments in this population in certain cognitive areas such as memory, executive function, attention, and speed of processing.2,28

Certainly, such cognitive deficits, suicidal ideation, and mental health issues can exert direct negative effects on physical health as well as interfering with adherence to HIV medications (such as not remembering or being apathetic about taking medications).29,30 These cognitive deficits, suicidal ideation, and mental health concerns may be aggravated by financial concerns, multi-morbidity, and other such stressors. These stressful situations may also increase cortisol levels, exacerbate other health problems such as substance use, and compromise self-care behaviors such as sleep hygiene; all of which can lead to poor cognitive and physical functioning.24

All of these barriers represent unique yet inter-related stressors that can contribute to poor functioning in each of the four major components of successful aging. With such stressors, it is understandable why someone aging with HIV may feel particularly overwhelmed, hopeless, and abandoned – not only by society, but perhaps from their beliefs, faith, religious communities, and even by God.31 Yet, despite such barriers to successful aging, many people with HIV still benefit from their religious and spiritual beliefs and actually thrive under such circumstances.

Spirituality of aging

Involvement in religious and spiritual practice has been found to correspond to better health-related outcomes regardless of age.32–35 Such involvement may provide one with social support, norms for healthy behaviors, and a sense of well-being which promotes better overall mood.36 But with advanced age, older adults have unique stressors that may compromise successful aging and are exacerbated when they are aging with HIV. Such stressors include multi-morbidity, diminished social supports, limited financial capacity, limited functional ability, and end-of-life concerns. Spirituality and religiousness can serve as buffers to life stress, by allowing individuals to interpret their life experiences in the context of their beliefs, which provide purpose and meaning in life, as well as promoting transcendence over circumstances, and bolstering feelings of inner resources and connections to others.10,36–39

As an example of such benefits, Lowry and Conco examined the role of spirituality in the lives of older adults in Appalachia.40 Using a qualitative study design, they asked participants a variety of open-ended questions about health, spirituality, and religiosity, as well as social supports. In general, these researchers found that spirituality protected these older adults from negative attitudes and declines in physical health. The primary themes that emerged included the belief that God is actively involved in their lives, God calls them to action, and God supports them at times of loss. In this study, it was clear that the participants’ personal relationship with God buffered them from the negative aspects of aging by providing them solace and a sense of purpose

Spirituality and coping with chronic disease

Just as in the gerontological literature, the chronic disease literature shows the biopsychosocial benefits of spirituality and religiosity in buffering one from the stressors of such diseases. Such benefits have been observed in numerous diseases including bipolar disorder,41 cancer,42 diabetes,34 and heart disease,35 as well as other stigmatizing diseases such as visual impairment.33 Such benefits have also been observed with HIV.21,43–48

Despite a history of HIV being particularly stigmatized by some religious communities,22,49 Lorenz and colleagues found adults with this disease had a high level (80%) of religious participation;50 of those, most reported that their religion (80%) and spirituality (65%) were “somewhat” or “very” important. Brennan and colleagues found that older adults with HIV had similar rates of religious participation to other groups of older adults. Participation remained high even among those who did not disclose their HIV status to their congregation, and 47% reported receiving support from their congregations.22 In a sample of 279 adults with HIV, Ironson and colleagues found religiosity and spirituality corresponded to lower cortisol levels, increased positive health behaviors, larger social supports, hope, and improved long-term survival among older adults with HIV.51 Similarly, in a sample of 450 HIV/AIDS outpatients, Szaflarski and colleagues found that nearly a third indicated feeling that their life was better now than before they were diagnosed with HIV.52 Specifically, they found that a 1 SD increase in the Duke Religion Index was related to a 68.5% increase in the odds ratio that life was better. Clearly, from these studies, spirituality and religious involvement is associated with better health outcomes in adults with HIV.

Yet, religion can hinder positive biopsychosocial outcomes. In a qualitative study, Miller interviewed African American gay men with AIDS about their religious involvement.53 Some reported rejection by their church for being gay or HIV positive. In fact, some who maintained a relationship with their church reported lower self-esteem. Clearly, although religiosity and spirituality can have positive biopsychosocial outcomes, it can also be a source of stress and may negatively impact self-care behavior. In a sample of 306 adults with HIV in the southern United States, those who considered that their disease was a punishment from God were more likely to miss taking their medication and had trouble keeping their medical appointments.54

Spirituality of aging with HIV

HIV presents several unique barriers to successful aging. As Figure 1 shows, older adults with HIV may be more vulnerable to a number of issues including stigma both for being older and having HIV. Yet, just as in the HIV and gerontological literatures, adults aging with HIV have also been shown to benefit from religiosity and spirituality.22,45,55 Having coped with stressful experiences over the course of their lives, older adults with HIV may have the capacity to negotiate difficult situations such as barriers to successful aging due to HIV by drawing upon their repertoire of coping strategies.56

Being diagnosed with HIV is a life event that may serve as a catalyst for growth and maturity. Many adults aging with HIV report that they grew spiritually from being diagnosed with HIV. In a sample of 50 adults with HIV, Vance found that 72% of older adults with HIV indicated that their spirituality changed as a result of being diagnosed;31 likewise, 44% considered HIV to be a blessing in that it helped them to dig into their spirituality and forced them to confront issues of health, self-care, and God’s purpose for their lives. Others have found that spirituality and religiosity do increase with a diagnosis of a disease. Sodestrom and Martinson found a similar effect to Vance’s finding, with 88% of cancer patients finding meaning in their illness through their beliefs and faith.57 Other studies examining spirituality in adults with HIV have found that spirituality levels are higher in older adults with HIV than younger adults with HIV;50,58 however, some studies do not detect such differences.45 Other research finds that levels of spirituality among older adults with HIV were the same or higher compared to other adults coping with chronic illness.44 These findings regarding the importance of spiritual and religious resources among older adults with HIV suggest that one could facilitate successful aging with HIV through spiritually-based interventions and practice modalities.

Implications for practice

Health professionals working with older adults with HIV need to assess the role of spirituality and religiosity and make an effort to include their findings in the management of the disease. Given the evidence that spirituality is a major component of successful aging with HIV (Figure 1), ignoring this important aspect of successful aging could contribute to poorer health outcomes. Older adults with HIV could benefit from a more comprehensive approach to disease management that incorporates their level of spirituality and religiosity, as well as appropriate referrals for those who need counseling in these and related areas of their lives. Such counseling may be of value to many with HIV as they confront and cope with issues of intimacy, fear, guilt, anger, and confusion over the disease.59 During counseling, religious and spiritual issues will undoubtedly emerge. Some issues may stem from anger at religious institutions for their particular views on HIV or homosexuality. Others may focus on broader spiritual issues including end-of-life concerns such as “Will I go to heaven?”; while others may be concerned about more basic questions such as “Does God still love me?”

Traditionally, secular counseling has steered away from incorporating matters of faith and spirituality into the psychodynamic setting; too often this is considered the sole domain of clergy and spiritual counselors.60 In the secular domain, Freud and others often considered the concept of God as a father image to be a form of wish fulfillment; in such a capacity, patients may not be able to work through deep personal issues due to adherence to strict religious doctrines or mores that limit personal growth. However, Freud and others also noted that religion and spirituality can serve as a catalyst for working through issues and promote coping, growth, and transcendence.61,62 Yet religion and spirituality can be treacherous psychological waters to navigate with some therapists suggesting that instead of drowning in such unpredictable and uncharted rapids, it is better to walk on the banks of reason and logic.

Likewise, spiritual and religious counseling has traditionally steered away from secular techniques, leaving the treatment of severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other more serious conditions to the medical community and maintaining their focus on faith-based approaches. But over the past few decades, spiritual and religious counseling has adopted more secular counseling techniques; this can be observed in training programs for clergy that incorporate more psychology classes and greater emphasis on the medical model.60 Similarly, secular counseling has acknowledged the importance of the spiritual and religious lives of patients and has recognized that spiritual and religious thoughts and imagery are a rich source of personal information.60,63

Given that 85%–90% of those in the United States report believing in God or a higher power and that some 71.5% actually pray once a week,64 ignoring matters of faith and spirituality is tantamount to ignoring the proverbial “elephant in the living room”. Clearly, religious and spiritual experiences are just as important to people as the objective circumstances of their lives. In fact, Gallup poll (cited by Foster)65 found that 66% of those in the United States reported that they would prefer to go to a counselor with spiritual beliefs and values if they were seeking a mental health professional. Others have also come to the realization that it is valuable to incorporate the spiritual in counseling.

For example, the well-known 12-step program, originally developed to address alcoholism, incorporates several concepts of God or a higher power to help resolve personal conflicts and provide a guide for living. In the first step of the 12 steps, it states “We admitted we were powerless over alcohol – that our lives had become unmanageable”.66 In this statement, alcohol can be substituted with any other recurrent problem whether it is unforgiveness, depression, a life-changing mistake, or even HIV. In fact, Potik suggested translating the 12-step program, normally used in alcohol and other addiction counseling, to other life situations such as adapting to a chronic disease.62 As Potik explains, these 12 steps can be used flexibly to help recover from a number of issues. The principles of the 12-step program can be used to help with a number of spiritual issues and emotions that are consistent and debilitating, whether the problem is fear of HIV, guilt over how one acquired HIV, regret over the life one could have had without HIV, or anger over how one has been treated due to one’s HIV status.

As seen in the literature on the spirituality of aging and HIV, issues of fear, guilt, regret, and anger are recurrent themes; such emotions can be powerful, crippling, and stymie one’s ability to move forward and live one’s life fully. Clinging to such toxic emotions can be likened to addiction in that it can destroy relationships, prevent one from maintaining or forming relationships, and even lead to other addictions such as alcohol to escape such feelings of despair. Such emotions also represent feelings of powerlessness as addressed in step one of the 12-step program – and could be articulated as “we are powerless over HIV”. In acknowledging this powerlessness, Potik explains that this is not “giving up” but rather it is a form of “acceptance”. By admitting such powerlessness, one opens up to a greater power beyond one’s own capability – whatever one’s nomenclature. This subsequently leads to step 2 – “Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity”. By such a fundamental reliance on this power, one opens up to the possibility that one can be made whole again. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to explore the other 10 steps, it is clear that the steps gradually build on each other to help one to acknowledge weaknesses, take inventory of strengths, and to maximize one’s ability to live the best one can, one day at a time. Such steps would appear to be valid mechanisms for coping with the powerlessness and unpredictability of being diagnosed and aging with a life-threatening chronic illness such as HIV.

Implications for research

For researchers studying the management of chronic illnesses like HIV, religious and spiritual resources represent a fascinating, meaningful, and beneficial way of optimizing health-related outcomes. The few research areas presented in this article focus on the development of hardiness and resilience, spirituality across groups, and the change of attitudes about HIV among communities of faith.

Since the concept of hardiness parallels aspects of spirituality, Vance, Struzick, and Masten proposed a daily cognitive-behavioral approach that employs exercises for developing characteristics of hardiness.55 In this cognitive-behavioral program, a client aging with HIV may be experiencing anxiety and depression. So the therapist would help the client identify sources and icons of optimism and strength. Such sources could be inspirational songs, television shows, movies, books, poems, mantras, prayers, and art. The key to identifying such sources is that they must be personally and intensely meaningful to the client; often, these are very spiritual in nature. By identifying such salient sources, they can be woven into a cognitive-behavioral program to be used by the client on a daily basis. Examples of such structured features of the program may include the following instructions: 1) “Before getting out of bed each day, meditate for at least a few minutes about how you are going to take care of yourself so you can take care of your friends and family”, 2) “Repeat the following mantra every time you ride the elevator at work – ‘It is fine to fall, and even better to rise again,’” 3) “Enjoy positive media such as Star Trek, Robin Williams, and gospel music”, and 4) “When you go to bed, write in your journal the two most positive things that have happened to you today”. Obviously, such an approach would include spiritual and/or religious activities, be more detailed and descriptive, and contain behaviorally-objective goals to ensure that the target behaviors occur in order to change thoughts and behaviors to facilitate a hardy attitude. By developing a more hardy and proactive attitude, one should be better adjusted psychologically and spiritually to deal with some of the barriers to successful aging with HIV.

A similar approach has also been studied in a group intervention to help adults with HIV. Tarakeshwar, Pearce, and Sikkema created an eight-session group intervention to address issues specific to HIV;67 a focus on spirituality was included. Using a pre-post experimental design in this pilot study, researchers found that after completing this intervention, participants reported having more positive spiritual coping skills and feeling less depressed.

Spirituality may also support cognitive functioning in older adults with HIV. Many adults with HIV have been observed to suffer from subclinical cognitive deficits; there are concerns that with advancing age that such deficits will become more profound.2 Since HIV is also associated with depression and anxiety, such negative affect has also been shown to negatively impact cognitive functioning.2 Thus, interventions that reduce such negative affect may actually improve cognitive functioning.24 Promoting spirituality as a coping resource may help reduce such negative affect and subsequently help promote successful cognitive aging in this population. Also, certain spiritual practices, such as meditation or attending religious meetings, have been shown to be stimulating cognitive exercises in their own right. In this sense, spiritual practices support the cognitive component of successful aging as well.68 Despite these connections in the literature, a more systematic evaluation of how spirituality can affect successful cognitive aging with HIV needs to be evaluated.

Despite such interventions that employ aspects of spirituality and religious coping, evidence suggests that different groups of people may derive differential benefits from spirituality and religious involvement. In a series of studies, Vance and colleagues69 surveyed 421 adults with HIV from across Alabama. A structural equation model was constructed that examined the effects of years since diagnosis with HIV, age, and education on the mediating role of religious activity on three biopsychosocial outcomes (ie, health status, social support, and mood). In the overall sample, older participants engaged in more religious activities, and engagement in such activities was predictive of greater perceived social support. However, when the same structural equation model was examined for different subgroups in the sample (ie, men, women, African Americans, Caucasians, homosexuals, heterosexuals); women, African Americans, and homosexuals seemed to benefit more from such religious activities.70–73 However, these results are in contrast with other findings. In a study of older adults without HIV, McFarland73 found that men tended to receive more mental health benefits from religious involvement than women. Why such differential benefits occur is not clear. More research into this area is needed.

Finally, as already mentioned, religion and spirituality has not always been a source of solace or strength for many with HIV. Historically, at the beginning of the epidemic especially, several religious enclaves denounced those with HIV, offering recrimination to “immoral” behaviors such as intravenous drug use, homosexuality, and sex outside of marriage. These bombastic views were internalized for some with the disease. In their sample of 90 adults with AIDS, Kaldjian, Jekel, and Friedland found that 17% of adults with AIDS reported that their disease was a punishment from God.74 Such guilt and self-denigration can obviously hinder mental health.75 Brennan and colleagues report that stigma is a major factor in the failure of older adults with HIV to access support from their religious congregations, noting that many fear rejection due to moral judgments because of their seropositive status.22 Over time, with more education and knowledge about HIV, such harsh views may have softened in some religious communities as well as in society overall. Whether this change in societal attitudes has increased access to religious and spiritual sources of solace and support among older adults with HIV remains unknown.

Conclusion

Successful aging with HIV is possible; however, studies indicate several potential obstacles such as decreased social support, with many lacking intimate relationships; increased multi-morbidity; and potential financial difficulties from years of being unable to work and prepare for retirement.2 These factors can be a source of regret, depression, and anger. Fortunately, religious and spiritual resources represent a source of coping for many, with the caveat of being able to access such resources without the barriers of stigma and moral recrimination. It is important for mental health professionals, both religious and secular, to recognize that many of their clients with HIV are aging within a spiritual context; a context that may be turbulent or serene based upon their personal history and spiritual interpretation of their lives. Social support from a religious or spiritual body of like-minded people could certainly help some older adults with HIV. Still, mental health professionals will need to be creative in helping the older client with HIV to embrace their powerlessness over the disease itself in order to tap into inner strengths, become hardy, and age successfully.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Mack K, Ory M. AIDS and older Americans at the end of the Twentieth Century. JAIDS. 2003;33(2):S68–S75. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vance DE. Aging with HIV: Bringing the latest research to bear in providing care. Am J Nurs. 2010;110(3):42–47. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000368952.80634.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV/AIDS among persons aged 50 and older: CDC HIV/AIDS facts. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirk JB, Goetz MB. Human immunodeficiency virus in an aging population, a complication of success. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(11):2129–2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontologist. 1997;37:433–440. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowther MR, Parker MW, Achenbaum WA, Larimore WL, Koenig HG. Rowe and Kahn’s model of successful aging revisited: Positive spirituality – the forgotten factor. Gerontologist. 2002;42(5):613–620. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pargament KI. Spiritually integrated psychotherapy: Understanding and addressing the sacred. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sulmasy D. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. The Gerontologist. 2002;42(Spec No 3):24–33. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bienefeld D, Yager J. Issues of spirituality and religion in psychotherapy supervision. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sc. 2007;44(3):178–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koenig HG. Religion and aging. Rev Clin Gerontol. 1993;3:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vance DE, Robinson PF. Reconciling successful aging with HIV: A biopsychosocial overview. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2004;3(1):59–78. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vance DE, Woodley RA. Strengths and distress in adults who are aging with HIV: A pilot study. Psychol Rep. 2005;96(2):383–386. doi: 10.2466/pr0.96.2.383-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. pp. 181–221. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vance DE, Mugavero M, Willig J, Raper JL, Saag MS. Aging with HIV: A cross-sectional study of comorbidity prevalence and clinical characteristics across decades of life. J Assoc Nurse AIDS Care. 2011;22(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karpiak SE, Brennan M. The emerging population of older adults with HIV and introduction to the ROAH study. In: Brennan M, Karpiak SE, Shippy RA, Cantor MH, editors. Older adults with HIV: An in-depth examination of an emerging population. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cantor MH, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. The social support networks of older adults with HIV. In: Brennan M, Karpiak SE, Shippy RA, Cantor MH, editors. Older adults with HIV: An in-depth examination of an emerging population. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. pp. 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shippy RA, Karpiak SE. The aging HIV/AIDS population: Fragile social networks. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(3):146–154. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331336850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Stigma and psychological distress among older adults with HIV: The mediating role of spirituality. In: Agaibi C, Brennan M, editors. Spirituality: An Essential Component of Resilience Despite Personal Loss or Terminal Illness; Symposium presented at the 117th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association; 2009 Aug; Toronto, Canada. (Chairs), [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emlet CA. “You’re awfully old to have this disease”: Experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS. Gerontologist. 2006;46(6):781–790. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nichols JE, Speer DC, Watson BJ, et al. Aging with HIV: Psychological, social, and health issues. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotton S, Puchalski C, Sherman S, et al. Spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 5):S5–S13. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan M, Strauss SM, Karpiak SE. Religious congregations and the growing needs of older adults with HIV. J Relig Spiritual Aging. 2010;22(4):307–328. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vance DE. Self-rated emotional health in adults with and without HIV. Psychol Rep. 2006;98(1):106–108. doi: 10.2466/pr0.98.1.106-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vance DE, Ross J, Moneyham L, Farr K, Fordham P. A model of cognitive decline and suicidal ideation in adults aging with HIV. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;42(3):150–163. doi: 10.1097/jnn.0b013e3181d4a35a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whetten K, Reif SS, Napravnik S, et al. Substance abuse and symptoms of mental illness among HIV-positive persons in the Southeast. South Med J. 2005;98(1):9–14. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000149371.37294.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care. 2010;16:1–10. doi: 10.1080/09540120903280901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalichman SC, Heckman T, Kochman A, Sikkema K, Bergholte J. Depression and thoughts of suicide among middle-aged and older persons living with HIV-AIDS. Psychiat Serv. 2000;51(7):903–907. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hardy D, Vance D. The neuropsychology of HIV/AIDS in older adults. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19(2):263–272. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Applebaum A, Brennan M. Mental health and depression. In: Brennan M, Karpiak SE, Shippy RA, Cantor MH, editors. Older adults with HIV: An in-depth examination of an emerging population. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinkin CH, Hardy DJ, Mason KI, et al. Medication adherence in HIV-infected adults: Effects of patient age, cognitive status, and substance use. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S19–S26. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200418001-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vance DE. Spirituality of living and aging with HIV: A pilot study. J Relig Spiritual Aging. 2006;19(1):57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferraro KF, Albrecht-Jensen CM. Does religion influence adult health? J Sci Study Relig. 1991;30(2):193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brennan M. Spirituality and religiousness predict adaptation to vision loss among middle-age and older adults. Int J Psychol Relig. 2004;14(3):193–214. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newlin K, Melkus GD, Tappen R, Chyun D, Koenig HG. Relationships of religion and spirituality to glycemic control in Black women with type 2 diabetes. Nurs Res. 2008;57(5):331–339. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000313497.10154.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beery TA, Baas LS, Fowler C, Allen G. Spirituality in persons with heart failure. J Holist Nurs. 2002;20(1):5–25. doi: 10.1177/089801010202000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell J, Weatherly D. Beyond church attendance: Religiosity and mental health among rural older adults. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2000;15(1):37–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1006752307461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brennan M. Spirituality and psychosocial development in middle-age and older adults with vision loss. J Adult Dev. 2002;9(1):31–46. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koenig HG, George LK, Titus P. Religion, spirituality, and health in medically ill hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(4):554–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wink P, Dillon M. Religiousness, spirituality, and psychosocial functioning in late adulthood: Findings from a longitudinal study. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(4):916–924. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowry LW, Conco D. Exploring the meaning of spirituality with aging adults in Appalachia. J Holist Nurs. 2002;20(4):388–402. doi: 10.1177/089801002237594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell L, Romans S. Spiritual beliefs in bipolar affective disorder: Their relevance for illness management. J Affect Disorders. 2003;75(3):247–257. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fryback PB, Reinert BR. Spirituality and people with potentially fatal diagnoses. Nurs Forum. 1999;34(1):13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.1999.tb00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brennan M. Older men living with HIV: The importance of spirituality. Generations. 2008;32(1):54–61. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brennan M. Religiousness and spirituality. In: Brennan M, Karpiak SE, Shippy RA, Cantor MH, editors. Older adults with HIV: An in-depth examination of an emerging population. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuevas JE, Vance DE, Viamonte SM, Lee SK, South JL. A comparison of spirituality and religiousness in older and younger adults with and without HIV. J Spir Ment Health. 2010;12:273–287. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2010.518828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dalmida SG. Spirituality, mental health, physical health, and health-related quality of life among women with HIV/AIDS: Integrating spirituality into mental health care. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27:185–198. doi: 10.1080/01612840500436958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ironson G, Stuetzle R, Fletcher MA. An increase in religiousness/spirituality occurs after HIV diagnosis and predicts slower disease progression over 4 years in people with HIV. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 5):S62–S68. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tarkeshwar N, Khan N, Sikkema KJ. A relationship-based framework of spirituality for individuals. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(1):59–70. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crawford I, Allison KW, Robinson WL, Hughes D, Samaryk M. Attitudes of African-American Baptist ministers towards AIDS. J Community Psychol. 1992;20:304–308. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lorenz KA, Hays RD, Shapiro MF, Cleary PD, Asch SM, Wenger NS. Religiousness and spirituality among HIV-infected Americans. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(4):774–781. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ironson G, Solomon GF, Balbin EG, et al. The Ironson-Woods Spirituality/Religiousness Index is associated with long survival, health behaviors, less distress, and low cortisol in people with HIV/AIDS. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):34–48. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szaflarski M, Ritchey PN, Leonard AC, et al. Modeling the effects of spirituality/religion on patients’ perceptions of living with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S28–S38. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller RL. Legacy denied: African American gay men, AIDS, and the black church. Soc Work. 2007;52(1):51–61. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parsons SK, Cruise PL, Davenport WM, Jones V. Religious beliefs, practices, and treatment adherence among individuals with HIV in the southern United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(2):97–111. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vance DE, Struzick TC, Masten J. Hardiness, successful aging, and HIV: Implications for social work. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2008;51(3–4):260–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brennan M, Cardinali G. The use of pre-existing and novel coping strategies in adapting to age-related vision loss. Gerontologist. 2000;40(3):327–334. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sodestrom K, Martinson IM. Patients’ spiritual coping strategies: A study of nurse and patient perspectives. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1987;14(2):41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.World Health Organization WHOQOL-HIV for quality of life assessment among people living with HIV and AIDS: Results from the field test. AIDS Care. 2004;16:882–889. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331290194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holt JL, Houg BL, Romano JL. Spiritual wellness for clients with HIV/AIDS: Review of counseling issues. J Couns Dev. 1999;77(2):160–170. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Close RE. Ethical considerations in counselor-clergy collaboration. J Spir Ment Health. 2010;12(4):242–254. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Corey G. Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy. 4th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Potik D. In loving God’s spirit: Integrating the 12-step program into psychoanalytic psychotherapy. J Spir Ment Health. 2010;12(4):255–272. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Egan G. The skilled helper: A systematic approach to effective helping. 3rd ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bader C, Dougherty K, Froese P, et al. American piety in the 21st Century: New insights to the depth and complexity of religion in the US. Waco, TX: Baylor University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Foster G. For the record: The Foster Report. Christian Counseling Connection. 2009 Dec;15 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alcoholics Anonymous . Alcoholics Anonymous. 4th ed. New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tarakeshwar N, Pearce M, Sikkema K. Development and implementation of a spiritual coping group intervention for adults living with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2005;8:179–190. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Corsentino EA, Collins N, Sachs-Ericsson N, Blazer DG. Religious attendance reduces cognitive decline among older women with higher levels of depressive symptoms. J Gerontol A: Bio Sci and Med Sci. 2009;64(12):1283–1289. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vance DE, Antia L, Blanshan S, et al. A structural equation model of religious activities on biopsychosocial outcomes in adults with HIV. J Spir Ment Health. 2008;10(4):329–350. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ackerman M, Vance DE, Farr K. Religiosity and biopsychosocial outcomes in HIV: A SEM comparison of gender, race, and sexual orientation; Poster session presented at the annual convention of the Southern Nursing Research Society; Birmingham, AL. 2008 Feb. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ackerman ML, Vance DE, Antia L, et al. The role of religiosity in mediating biopsychosocial outcomes between African American and Caucasians with HIV. J Spir Ment Health. 2009;11:312–327. doi: 10.1080/19349630903307167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Suzuki-Crumly JK, Ackerman ML, Vance DE, et al. The role of religiosity in mediating biopsychosocial outcomes in homosexuals and heterosexuals with HIV: A structural equation modeling comparison study. J Spir Ment Health. 2010;12(3):209–223. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2010.498700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McFarland MJ. Religion and mental health among older adults: Do the effects of religious involvement vary by gender? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;65(5):621–630. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kaldjian LC, Jekel JF, Friedland G. End of life decisions in HIV positive patients: The role of spiritual beliefs. AIDS. 1998;12(1):103–107. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schumaker J. Mental health consequences of irreligion. In: Schumaker J, editor. Religion and mental health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 54–69. [Google Scholar]