Abstract

Gene and cell therapy holds tremendous promise for treating a variety of acquired and inherited disorders of the retina that impact on vision. Much has been written about the impact of vectors in delivering genes to cells of the retina in vivo. A critically important component of these kinds of therapies is the procedure used to introduce the cells or vectors. Drs. Stout and Francis provide a broad overview of gene and cell therapies for diseases of the retina, focusing on the procedures that could be used for delivery.

As pointed out in the papers in this special issue of Human Gene Therapy, the eye presents a unique opportunity to study the delivery of therapeutic genetic material.

There are many factors that make ocular gene therapy attractive and successful: (1) Almost all of the structures of the eye are visible and can be examined in the clinic by the slit lamp, and treatment response and potential complications can be visualized in real time; (2) a wide variety of objective, noninvasive imaging, and functional assessment modalities have been developed to evaluate visual function; (3) almost all the structures of the eye are surgically approachable via minimally invasive procedures that are performed in the outpatient setting under local anesthesia; (4) the eye is relatively immunoprivileged, with a robust blood–retinal barrier and essentially no lymphatic system; (5) the eye is a compact organ that requires relatively small volumes and doses of therapeutic agents; and, finally, (6) the vision loss associated with many ophthalmic diseases is symptomatic at stages that are amenable to intervention.

Given these advantages and the increasing number of gene and stem cell-based ocular therapies, what is important to know about the eye and its abilities? The retina is a multilayered neural structure that forms the inner lining of the posterior segment of the eye. Light entering the eye is focused onto the retina, where photons activate photopigments in the outer segments of the photoreceptors. The resultant electrical signals are relayed via bipolar cells and processed by a variety of intermediate neuronal cell types before relay by retinal ganglion cells to the central visual system. The photoreceptors lie in intimate association with the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a single layer of cells that serve numerous metabolic, nutritional, and immunological functions. Blood and nutrients are supplied to the human retina from two sources: the retinal arterioles and the choroid, which lies external to the RPE.

A large number of retinal degenerative disorders are recognized, principally affecting the photoreceptors and RPE in the outer retina. These include age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and the inherited retinal degenerations (IRDs). In both types of disease, vision loss occurs primarily because of progressive retinal photoreceptor death involving many common molecular processes. The need for new treatment strategies is compelling.

AMD is the leading cause of blindness in the developed world, affecting more than 10 million individuals in the United States alone (Friedman et al., 2004). Both genetic and environmental factors contribute to its development. Although the precise etiology of the condition remains to be elucidated, a major role for inflammation has been implicated (Bird et al., 1995; Klein et al., 2004; Haddad et al., 2006). One phenotypic hallmark of AMD is the accumulation of drusen (subretinal yellow deposits) at the macula. The number of drusen, or area that they occupy, correlates with risk of progression to the advanced form of the disease (Klein et al., 2002; Umeda et al., 2005). Advanced AMD is characterized by poor central vision following the development of (1) choroidal neovascularization (CNV), which leads to hemorrhage and scarring in the retina, also known as “wet AMD,” or (2) patches of retinal pigment epithelial and photoreceptor atrophy, “geographic atrophy” (GA), also known as “advanced dry AMD.” Strategies to treat “wet” AMD are aimed at destroying or encouraging regression of neovascularization (Stone, 2006). Even with the latest intraocular antiangiogenic treatment, most patients cannot expect visual improvement (Kaiser, 2006; Rosenfeld et al., 2006a). Although antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements may retard progression in patients with AMD who have the “dry” phenotype, there are no effective treatment options for most patients (Seddon and Hennekens, 1994; Bone et al., 2003; Blodi, 2004).

The inherited retinal degenerations (IRDs) are a diverse group of genetically determined disorders. Common examples include retinitis pigmentosa, Usher syndrome, and Stargardt macular dystrophy. Rarer degenerations of note include Leber congenital amaurosis (in particular those caused by mutations in the gene RPE65) and X-linked retinoschisis. The underlying genetic mutations are diverse, and although known in many cases, they are undefined in the majority of cases. In IRDs, a variety of patterns of visual failure may occur, including peripheral visual field loss progressing to complete blindness. There is no treatment for these conditions.

Targeting the Retina

Whether the therapeutic modality is gene therapy or cell-based, the most desirable delivery location is the outer retina because the majority of disease processes affect the cell types in this part of the tissue. The most favored target for agent delivery has therefore been the subretinal space (that potential space between the photoreceptors and RPE). Because current vector technology is unable to penetrate to the outer retina to any high degree and directed migration of transplanted cells has not been realized, agent delivery to the vitreous cavity results in only inner retinal targeting.

Because both gene and cell therapies can be delivered to a specific area, there is an opportunity to deliver an agent directly to the most affected region of the retina, for example, the macula for conditions such as AMD or Stargardt macular dystrophy. When the peripheral retina is involved, more diffuse treatment may be considered.

General Approaches to Gene Therapy for Ocular Disease

The simplest concept in gene therapy is that of gene replacement; it is best suited to recessive disease, in which a gene is rendered dysfunctional by a mutation. There are many recessively inherited retinal dystrophies, both autosomal and X-linked, making the eye a fertile testing ground for gene replacement strategies. The use of cell-specific promoters is advantageous to restrict transgene expression to appropriate cells. Examples in which this is important are diseases affecting primarily cone photoreceptors, for which inappropriate transgene expression in rod photoreceptors may be deleterious to function. Some diseases are caused by mutations in genes encoding secreted proteins. One such example is X-linked retinoschisis, in which mutations in RS1 affect expression of the secreted protein retinoschisin. In this case, cell-specific expression may be less important because preliminary evidence suggests distribution of recombinant retinoschisin to cell membranes distant from cells expressing the transgene.

Gene therapy is also an attractive approach when long-term expression of a “useful” gene is desired (Birch and Liang, 2007; Bressler, 2009). In the retina, inappropriate angiogenesis is a major cause of vision loss and the most frequent cause of blindness in working people (diabetic retinopathy) and older individuals (AMD). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been shown to be a major mediator of this process and, indeed, repeated intravitreal injections of humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibodies show efficacy in treating these conditions (Rosenfeld et al., 2006b). Strategies that employ antiangiogenic genes are being investigated for their potential to provide long-term suppression of abnormal blood vessel growth (Maclachlan et al., 2011).

Stem Cell Therapy

Stem cells themselves are of little utility when directly transplanted into the retina. Instead, it is those cell types (retinal progenitors or mature cells) differentiated from stem cells that show the greatest promise (Gamm et al., 2007). Such cells have been derived from a variety of sources including embryonic, induced pluripotential, nuclear transfer, fetal, and adult sources. Although the majority of research has focused on local delivery of cells to the eye, there is some evidence that systemic delivery of certain stem cell derivatives might successfully target neovascularization in the retina (Hou et al., 2010).

Two treatment paradigms are currently being considered: (1) Transplantation of cells to replace cells lost as part of retinal degenerative disease: because cells in the retina have little or no potential for self-regeneration or replication, transplantation of healthy replacement cells would appear likely to have efficacy. Measured success has so far been achieved largely in small animal models and, for example, a trial involving embryonic stem cell-derived RPE cells is due to begin this year; and (2) transplantation of cells that have metabolic, nutritional, neuroprotective, or antiangiogenic effects that act to prevent further host retinal cell loss and potentially rejuvenate previously diseased and dysfunctional cells.

Surgical Approaches

Surgical access to the multiple layers of the eye has evolved remarkably. Advances in microinstrumentation and the evolution of surgical techniques that allow safe, sutureless surgery have driven this evolution.

Intravitreal injection

The delivery of therapeutic agents into the vitreous cavity has become a routine procedure in all vitreoretinal clinics. This usually involves the injection of a VEGF-binding aptamer (pegaptinib) or antibody (bevacizumab or ranibizumab) through a 30-gauge needle introduced into the vitreous cavity through the sclera 3–4 mm posterior to the corneal limbus (Fig. 1). Patients with neovascular AMD often receive these injections on a monthly basis. Despite the ease of intravitreal injection, the delivery of viral vectors into the vitreous cavity of primates rarely results in transduction of the neurosensory retina or RPE. Epithelial cells of the ciliary body and the pars plana are routinely transduced by adeno-associated and lentiviral vectors injected into the vitreous cavity. The presence of an intact internal limiting membrane (the collagen-rich membrane that separates the vitreous from the neurosensory retina) is likely not the only barrier to transduction of the outer retina (photoreceptors) and the RPE by viral vectors introduced into the vitreous cavity, as peeling of this membrane in nonhuman primates fails to result in enhanced transduction efficiency.

FIG. 1.

Intravitreal injection.

Pars plana vitrectomy

The clear gelatinous vitreous can be removed without physiological consequence. As its noncovalent attachment to the retina is often implicated in the development of a retinal detachment (a break occurs in the retina and thus allows the accumulation of fluid between the retina and the RPE), removal of the vitreous and replacement with saline is a surgical procedure commonly used to repair retinal detachment. Surgical access to the subretinal space via pars plana vitrectomy involves a brief outpatient, often sutureless, procedure. This usually requires the placement of three “ports” (20-, 23-, or 25-gauge openings in the sclera) to allow (1) an infusion cannula (to replace the volume of vitreous removed with saline and thus maintain a normal intraoperative intraocular pressure), (2) a light pipe (to illuminate the intraocular surgical field), and (3) a microvitrector, which provides both suction and cutting functions required to remove the thick vitreous. In all species, the delivery of viral vectors into the subretinal space results in the most efficient transduction of the neurosensory retina and RPE. Manipulation of the vitreous without vitrectomy is often complicated by the development of a retinal detachment, and therefore most procedures that involve access to the posterior segment (including the injection of material into the subretinal space) are performed in conjunction with a vitrectomy. Gene or cell therapy protocols that deliver viral vectors into the subretinal space typically involve a vitrectomy followed by the introduction of the therapeutic agent into the subretinal space via the smallest possible entry site through the retina (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Subretinal injection.

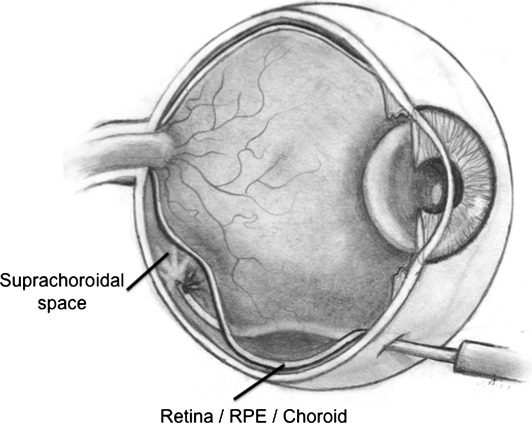

Suprachoroidal cannulation

An alternative to vitrectomy and subretinal injection is emerging as a surgical approach able to deliver therapeutic agents to the retina and RPE, without having to violate the vitreous cavity. Small silicone catheters (MicroTrac catheter; iScience Interventional, Menlo Park, CA) may be passed through an opening in the eye wall (sclera) into the suprachoroidal space (posterior to the vitreous, retina, RPE, and vascular choroidal layer) and manipulated posteriorly so that material can be injected beneath the macular area (Fig. 3). Viral vectors delivered in this fashion have been shown to transduce choroidal endothelial cells, RPE, and cells of the neurosensory retina (personal observation). This technique may prove safer than vitrectomy plus subretinal injection, as there is no removal of the vitreous and no iatrogenic retinal hole.

FIG. 3.

Suprachoroidal injection.

Dosing Considerations in Cell Transplantation

It is obvious that standard pharmacokinetic analysis becomes redundant when trying to define the optimal dose of cells for retinal transplantation. In addition, there are currently no reliable methods of monitoring the survival of transplanted cells in the retina, either locally or by serum analysis. It is also not established that cell transplantation will show a conventional dose response, in which a higher dose typically results in better efficacy until a maximal effect is reached. Because cells have a certain volume and surface area, injecting more cells into a fixed area might not result in additional benefit. This is pertinent to both treatment paradigms (cell replacement and cell rescue).

Location and Distribution of Transplanted Cells

Infusion of cells in free suspension through a retinotomy into a subretinal bleb results in free distribution of the cells within the volume of the bleb. It is then expected that settling of the cells in the walls of the bleb occurs due to the action of gravity and other forces such as thermal currents. The speed at which this occurs will be determined by cell-specific characteristics as well as the dynamic properties of the carrier medium. Over a matter of hours, the remaining free extracellular fluid in the bleb is absorbed and the bleb flattens and then resolves, resulting in apposition once more of the photoreceptors to the RPE. It is presumed that cells remaining in the flattened bleb are therefore “trapped” in the subretinal space and localized to this delivery area. As such, it would be expected that potentially the greatest beneficial effects will be localized to the bleb area or perhaps somewhat beyond if cells elaborate soluble trophic factors. However, as the bleb flattens, the boundary may extend, thereby distributing the cells over a wider area. This is advantageous in that it may allow a small bleb to be created and yet result in a larger treatment area. A disadvantage, however, would be uncontrolled bleb extension into visually significant regions such as the fovea.

Cell reflux out of the bleb through the retinotomy and into the vitreous cavity is a major consideration. Retinotomies are generally not self-closing and there is limited potential to seal these at the end of the surgical procedure. Reflux of cells may result in significant loss of efficacy and potentially deleterious effects of cells being in the vitreous, for example, development of epiretinal membranes or retinal traction.

The migratory potential of transplanted cells is not well appreciated. Certain progenitors appear to have migratory potential both within the retina and distant from the delivery site, at least in rodent models of retinal degeneration. In all likelihood, migration is cell specific; it is a critical property to investigate in order to best plan clinical application. For example, it would be a major advantage if cells could be transplanted to a relatively visually insignificant peripheral region of the retina and yet be anticipated or guided to treat the macula.

Accessorizing Stem Cells

Some of the uncertainties about cell distribution and dose requirements can be mitigated if cells are encapsulated or transferred in extracellular matrices/scaffolds or grown on synthetic sheets. Further modification of these agents may also improve cell engraftment and attachment to the host retina (Sugino et al., 2011).

Encapsulated Cell Technology

Cells genetically engineered to produce a certain diffusible factor may be encapsulated in an Encapsulated Cell Technology device (Neurotech, Lincoln, RI), in a synthetic semipermeable membrane that can be implanted and secured with a suture in the vitreous cavity. Nutritional support of the cells is derived from the vitreous itself. Preliminary success with this technology has been reported for AMD and retinitis pigmentosa (Bush et al., 2004; Sieving et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2011).

Polymer scaffolds

Polymer scaffolds have been used to improve cell survival after implantation (Tao et al., 2007). Such scaffolds have evolved steadily, with increasing sophistication, to avoid the inflammation and fibrosis that occurred with the first-generation poly(l-lactic acid)/poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLLA/PLGA)-based polymers (Tomita et al., 2005). Another requirement was that the scaffold be biodegradable; a limitation of the polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA)-based technology (Tao et al., 2007). The latest generation scaffolds are based on biodegradable polycaprolactone (PCL) (Redenti et al., 2008) and can be manufactured microtopographically (Steedman et al., 2010), which appears to enhance survival and promote differentiation of retinal precursor cells toward more mature cell types. Cotransplantation of biodegradable PLGA microspheres fabricated to release factors that alter the extracellular matrix, for example, matrix metalloproteinase-2, has been shown to further enhance integration of cells into host retinal tissue (Sodha et al., 2011; Yao et al., 2011).

Retinal sheets

In most retinal diseases, more than one cell type or retinal layer is affected and the possibility of successful transplantation of cells in sheets has been explored, either single (Seiler and Aramant, 2005) or multilayer sheets of cells (Seiler et al., 2010).

Immune Considerations

“Immune privilege” describes the observation that tissue grafts in certain organs show extended survival and do not appear in invoke a full systemic immune response (Jiang et al., 1993). The subretinal space of the eye is considered one such compartment (Jiang et al., 1994; Grisanti et al., 1997) not only because it is avascular but also because RPE cells express cell surface markers and secrete factors that modify immune-mediated inflammatory responses (Enzmann et al., 2000, 2002). Questions remain, however, concerning whether this immune privilege extends to pathological states in which, for example, the RPE is deficient, as in AMD, or the postsurgical retina after vitrectomy and retinotomy. It is also unknown what immune response would be elicited by retreatment, which is likely to be necessary in clinical practice when both eyes are treated sequentially, or for long-term efficacy in the same eye.

The treatment of disease via the transfer of therapeutic genetic or cellular material is perhaps most mature in the eye. Protocols to treat inherited retinal degenerations as well as neovascular disease are underway and appear to be safe as well as therapeutic. The papers presented in this issue of Human Gene Therapy mark this rate of progress and help point the way for the next round of trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following funding sources: NIH/NEI (R01021214; P.F.), the Clayton Foundation for Research, the Foundation Fighting Blindness (P.F.), and Research to Prevent Blindness (P.F. and unrestricted grant to the Casey Eye Institute). The authors would like to thank Andrew J. Stout for his assistance with this manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no relevant commercial associations or competing financial interests.

References

- Birch D.G. Liang F.Q. Age-related macular degeneration: a target for nanotechnology derived medicines. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2007;2:65–77. doi: 10.2147/nano.2007.2.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A.C. Bressler N.M. Bressler S.B., et al. International ARM Epidemiological Study Group. An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1995;39:367–374. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blodi B.A. Nutritional supplements in the prevention of age-related macular degeneration. Insight. 2004;29:15–16. ; quiz 17–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone R.A. Landrum J.T. Guerra L.H. Ruiz C.A. Lutein and zeaxanthin dietary supplements raise macular pigment density and serum concentrations of these carotenoids in humans. J. Nutr. 2003;133:992–998. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.4.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressler N.M. Antiangiogenic approaches to age-related macular degeneration today. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:S15–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush R.A. Lei B. Tao W., et al. Encapsulated cell-based intraocular delivery of ciliary neurotrophic factor in normal rabbit: Dose-dependent effects on ERG and retinal histology. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:2420–2430. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enzmann V. Faude F. Wiedemann P. Kohen L. The local and systemic secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 after transplantation of retinal pigment epithelium cells in a rabbit model. Curr. Eye Res. 2000;21:530–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enzmann V. Hollborn M. Kuhnhoff S., et al. Influence of interleukin 10 and transforming growth factor-β on T cell stimulation through allogeneic retinal pigment epithelium cells in vitro. Ophthalmic Res. 2002;34:232–240. doi: 10.1159/000063875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D.S. O'Colmain B.J. Munoz B., et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–572. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamm D.M. Wang S. Lu B., et al. Protection of visual functions by human neural progenitors in a rat model of retinal disease. PLoS One. 2007;2:e338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisanti S. Ishioka M. Kosiewicz M. Jiang L.Q. Immunity and immune privilege elicited by cultured retinal pigment epithelial cell transplants. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997;38:1619–1626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad S. Chen C.A. Santangelo S.L. Seddon J.M. The genetics of age-related macular degeneration: A review of progress to date. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2006;51:316–363. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou H.Y. Liang H.L. Wang Y.S., et al. A therapeutic strategy for choroidal neovascularization based on recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells to the sites of lesions. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:1837–1845. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.Q. Jorquera M. Streilein J.W. Subretinal space and vitreous cavity as immunologically privileged sites for retinal allografts. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1993;34:3347–3354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.Q. Jorquera M. Streilein J.W. Immunologic consequences of intraocular implantation of retinal pigment epithelial allografts. Exp. Eye Res. 1994;58:719–728. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser P.K. Antivascular endothelial growth factor agents and their development: Therapeutic implications in ocular diseases. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2006;142:660–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. Klein B.E. Tomany S.C., et al. Ten-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1767–1779. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. Peto T. Bird A. Vannewkirk M.R. The epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2004;137:486–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclachlan T.K. Lukason M. Collins M., et al. Preclinical safety evaluation of AAV2-sFLT01: A gene therapy for age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:326–334. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redenti S. Tao S. Yang J., et al. Retinal tissue engineering using mouse retinal progenitor cells and a novel biodegradable, thin-film poly(ɛ-caprolactone) nanowire scaffold. J. Ocul. Biol. Dis. Infor. 2008;1:19–29. doi: 10.1007/s12177-008-9005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld P.J. Brown D.M. Heier J.S., et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006a;355:1419–1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld P.J. Rich R.M. Lalwani G.A. Ranibizumab: Phase III clinical trial results. Ophthalmol. Clin. North Am. 2006b;19:361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ohc.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon J.M. Hennekens C.H. Vitamins, minerals, and macular degeneration: Promising but unproven hypotheses. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1994;112:176–179. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090140052021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler M.J. Aramant R.B. Transplantation of neuroblastic progenitor cells as a sheet preserves and restores retinal function. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2005;20:31–42. doi: 10.1080/08820530590921873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler M.J. Rao B. Aramant R.B., et al. Three-dimensional optical coherence tomography imaging of retinal sheet implants in live rats. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2010;188:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieving P.A. Caruso R.C. Tao W., et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) for human retinal degeneration: Phase I trial of CNTF delivered by encapsulated cell intraocular implants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:3896–3901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600236103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodha S. Wall K. Redenti S., et al. Microfabrication of a three-dimensional polycaprolactone thin-film scaffold for retinal progenitor cell encapsulation. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2011;22:443–456. doi: 10.1163/092050610X487738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steedman M.R. Tao S.L. Klassen H. Desai T.A. Enhanced differentiation of retinal progenitor cells using microfabricated topographical cues. Biomed. Microdevices. 2010;12:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s10544-009-9392-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone E.M. A very effective treatment for neovascular macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:1493–1495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe068191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugino I.K. Sun Q. Wang J., et al. Comparison of fetal RPE and human embryonic stem cell derived-RPE (hES-RPE) behavior on aged human Bruch's membrane. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tao S. Young C. Redenti S., et al. Survival, migration and differentiation of retinal progenitor cells transplanted on micro-machined poly(methyl methacrylate) scaffolds to the subretinal space. Lab on a Chip. 2007;7:695–701. doi: 10.1039/b618583e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita M. Lavik E. Klassen H., et al. Biodegradable polymer composite grafts promote the survival and differentiation of retinal progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1579–1588. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda S. Suzuki M.T. Okamoto H., et al. Molecular composition of drusen and possible involvement of anti-retinal autoimmunity in two different forms of macular degeneration in cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) FASEB J. 2005;19:1683–1685. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3525fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J. Tucker B.A. Zhang X., et al. Robust cell integration from co-transplantation of biodegradable MMP2-PLGA microspheres with retinal progenitor cells. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K. Hopkins J.J. Heier J.S., et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor delivered by encapsulated cell intraocular implants for treatment of geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]