Abstract

Background

Diabetes group clinics can effectively control hypertension, but data to support glycemic control is equivocal. This study evaluated the comparative effectiveness of two diabetes group clinic interventions on glycosolated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels in primary care.

Methods

Participants (n = 87) were recruited from a diabetes registry of a single regional VA medical center to participate in an open, randomized comparative effectiveness study. Two primary care based diabetes group interventions of three months duration were compared. Empowering Patients in Care (EPIC) was a clinician-led, patient-centered group clinic consisting of four sessions on setting self-management action plans (diet, exercise, home monitoring, medications, etc.) and communicating about progress with action plans. The comparison intervention consisted of group education sessions with a diabetes educator and dietician followed by an additional visit with one’s primary care provider. HbA1c levels were compared post-intervention and at one-year follow-up.

Results

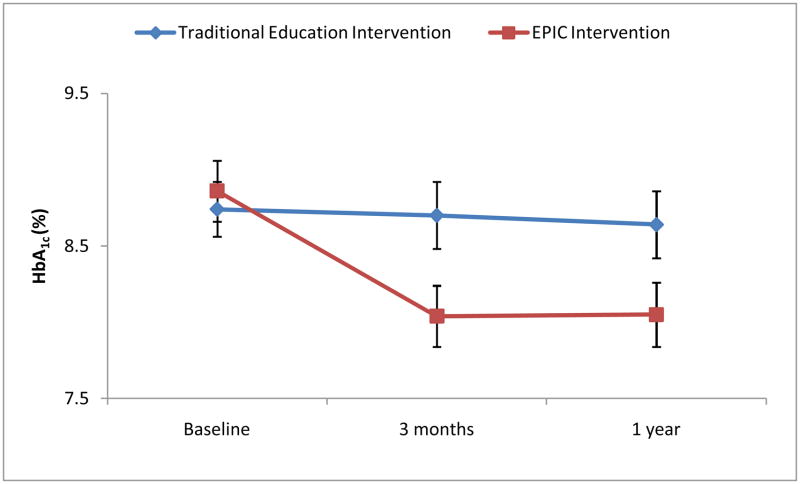

Participants in the EPIC intervention had significantly greater improvements in HbA1c levels immediately following the active intervention (8.86 to 8.04 vs. 8.74 to 8.70, mean [SD] between-group difference 0.67±1.3, P=.03) and these differences persisted at 1 year follow-up (.59±1.4, P=.05). A repeated measures analysis using all study time points found a significant time-by-treatment interaction effect on HbA1c levels favoring the EPIC intervention (F(2,85) =3.55, P= .03). The effect of the time-by-treatment interaction appears to be partially mediated by diabetes self-efficacy (F(1,85) =10.39, P= .002).

Conclusions

Primary care based diabetes group clinics that include structured goal-setting approaches to self-management can significantly improve HbA1c levels post-intervention and maintain improvements for 1-year.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00481286

Keywords: diabetes, group clinics intervention, goal-setting, HbA1c, self-efficacy

Diabetes is a serious and growing public health problem.1 The prevalence and morbidity of diabetes are greater among older adults who often have multiple chronic morbidities.2;3 Selfmanagement skills are an essential means of reducing morbidity and health services use among older, comorbid diabetics.4;5 However, delivery of effective self-management education and support can be difficult in traditional primary care, even among patients with access to care, medications, and diabetes educators but have persistently uncontrolled diabetes.6 Many primary care clinics have few personnel trained to effectively deliver self-management education and support for chronic diabetes care. Furthermore, diabetes self-management is often poorly integrated with the doctor-patient encounter, and evidence linking self-management activities and health outcomes are often indirect at best.5;7

Rather than a parallel form of treatment, self-management functions best as a method whereby patients integrate specific diabetes treatment recommendations (medications, home monitoring, diet and exercise, prescriptions, etc.) into the context of their daily routines.7 Effective self-management includes collaborative framing of specific self-management goals (goal-setting), feedback regarding structured activities patients do on a daily basis to reach their self-management goals (action plans) and proactive communication with clinicians about the success of self-management and the treatment plan as a whole.8;9 The effectiveness of an action plan can be enhanced by increasing patients’ confidence to carry out the behavior needed to attain desired goals (self-efficacy).8;10 Activated patients are more adherent to medications and recommended lifestyle changes, and more likely to report their experiences with medications, including adverse events like hypoglycemia and home monitoring results like fasting capillary glucose.6;9 Communication from activated patients is more likely to prompt changes in medication dosages leading to better diabetes outcomes.9

Shared medical appointments (group clinics) are a potential method of integrating selfmanagement support with routine diabetes care to reach the treated but uncontrolled patients with diabetes. Group clinics are associated with improvements in some diabetes outcomes and urgent care visits.11–14 However, randomized studies of group clinics using intensive medical management coupled with didactic models of self-management education have demonstrated mixed results when compared with routine diabetes care.15;16 These diabetes mellitus (DM) group clinics have been critiqued for focusing largely on the efficiency of medical management and a clinician-centric approach to diabetes education.17 To adequately determine the effectiveness of diabetes group clinics relative to routine diabetes care, medical management should be coupled with interventions that focus on how treatment plans are translated by patients into self-management goals (goal-setting) and then integrated into the context of their daily lives (action plans).

The objective of this study was to conduct a randomized comparative effectiveness trial of alternative diabetes group clinic approaches in a chronic care population with treated but uncontrolled diabetes. The trial compared DM group education plus routine primary care with a diabetes group intervention focused on training patients to integrate their providers’ treatment plans into collaborative self-management goals and action plans. The effectiveness of both groups was compared using HbA1c levels and diabetes self-efficacy immediately after the interventions and at 1-year follow-up.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This study was an open, randomized pilot trial comparing the effectiveness of two group self-management interventions on glycemic control. The study enrolled patients receiving routine primary care at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas. We screened and recruited participants between August 2007 and March 2008. The trial compared a novel intervention called “Empowering Patients in Chronic Care” (EPIC), with a diabetes and nutrition education intervention. After the active intervention period, participants in both arms received usual primary care. The primary outcome measure was improvement in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels at the conclusion of the active intervention period and one year after randomization.

Study participants were recruited overwhelmingly from the MEDVAMC primary care patient registry. Referrals from primary care providers (PCPs) and advertisements in outpatient clinics were infrequent sources of study participants. Patients in the primary care registry were sent an invitation letter describing the study and participant expectations including attendance at multiple group visits if they met the following eligibility criteria. Inclusion criteria defined eligibility to individuals aged 50–90 years, who have a primary care provider and a previous diagnosis of type II diabetes mellitus with a mean HbA1c ≥7.5% on all measurements in the last 6 months prior to study entry. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of dementia or a serum creatinine ≥ 2.5 mg/dl. Participants responding to the invitation letter or advertisement were asked to contact study personnel, who then obtained informed consent and baseline assessments prior to randomization. Participants with HbA1c< 7.0% at baseline despite higher historic HbA1c were excluded. The study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and by the MEDVAMC research and development committee.

Randomization and Group Assignment

After enrollment, participants were randomized to either the EPIC or traditional education interventions using a block randomization of 10. Allocation of treatment group assignment was blinded using sequentially numbered and sealed envelopes. Research personnel assisted with the assignment of participants to cohesive groups of 5–7 individuals for both the EPIC and traditional education interventions. Group assignments were maintained for all intervention sessions to facilitate peer interactions and relationships within groups.

Interventions

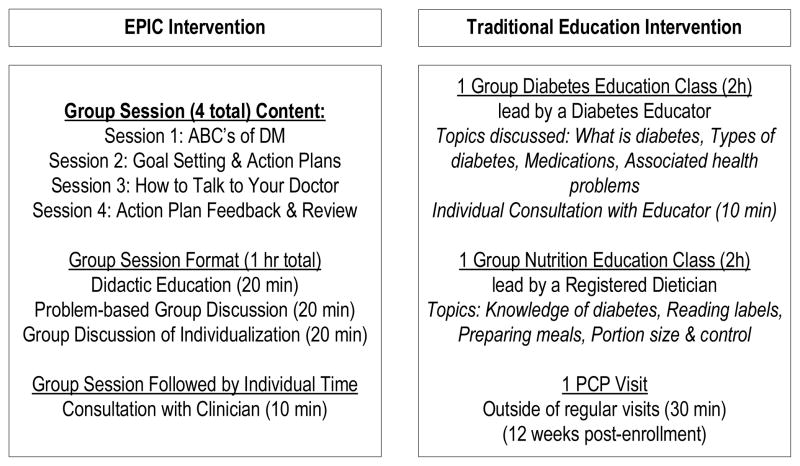

The EPIC Intervention consisted of four group sessions occurring every three weeks over a three month period (see Figure 1). Each session consisted of one-hour of group interaction facilitated by a study clinician trained in goal-setting and action planning methodology.8;18 After the hour-long group session, each participant had 10 minutes of individual interaction with the study clinician. Peer discussion of the intervention contents was encouraged while waiting for one’s interaction with the clinician. Each session had a different overall theme focusing on: The Diabetes ABCs (HbA1c, blood pressure, cholesterol), How to make Diabetes Goals and Action Plans, How to Talk to Your Doctor, and Action Plan Feedback (See appendix for more detailed descriptions of each session). The Diabetes ABCs session instructed participants about common risk markers for diabetes (i.e., HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, and cholesterol) and provided participants with their individual values for these three markers, taken from baseline measurements. The second session introduced elementary principles of goal-setting theory (goal specificity, difficulty, and importance), and guided participants in designing personalized diabetes goals and action plans.19 Goals focused primarily on diet and exercise changes, home monitoring of blood sugar and medication effects, and communication with PCPs about medications. Patients also developed goals about sleep, pain, and other barriers to self-management. The third session described and modeled proactive patient behavior, effective doctor-patient communication, and how to develop and obtain feedback on goals and action plans during clinical encounters.9;20 The fourth session allowed for constructive reporting and feedback on participants’ performance with their action plans with peers and the study clinician. Three study clinicians, primary care physicians at the MEDVAMC, directed the sessions (see appendix for information about training of study clinicians).

Figure 1. Intervention group description.

DM indicates diabetes mellitus, PCP indicates primary care provider

For each EPIC session, the group interaction was divided into three 20-minute blocks, each conveying the session theme using different modalities: (1) clinician-led discussion of didactic materials from a participant manual, (2) group discussion of problem-based exercises from the manual, and (3) peer-supported application of the session theme to one’s daily life (see Figure 1). During the one-on-one consultation with the study clinician, participants discussed their diabetes status, received feedback on their specific diabetes goal and action plan, and addressed medication related issues. Study clinicians sent a research note to PCPs after each session consisting of participants’ Diabetes ABCs status, the specific diabetes goals and action plans discussed, and any changes made to prescribed medication type and dosage due to side effects or other issues raised by patients. Action plans for nearly all patients included taking medications prescribed by PCPs and discussing subjective and objective effects of medications with PCPs.

Participants randomized to the traditional education intervention attended two distinct group sessions led by a diabetes nurse educator and a certified diabetes dietician. The nurse educator covered diabetes topics, including diabetes physiology, health problems, types of diabetes, and medications and dosing. At the end of the didactic portion, each participant received a 10 minute individual consultation with the nurse educator regarding their current HbA1c levels. The dietician covered topics about knowledge of diabetes, reading food labels, preparing meals, and portion size and control. Each session was two hours long. In addition, participants had a (20–30 minute) consultation scheduled after completing the education groups with their PCP. PCPs were instructed to focus on diabetes self-management and treatment plans.

Outcomes and Measurements

The primary outcome was HbA1c level measured by the clinical laboratory at the MEDVAMC using a standardized method of ion-exchange, liquid chromatography. Participants completed questionnaires at baseline that included socio-demographic information, a diabetes self-efficacy scale,21 and a diabetes-specific knowledge and understanding scale.22 The Diabetes Self-Efficacy scale is an 8 item measure evaluating respondents’ confidence in performing specific diabetes management tasks, such as diet, exercise, blood glucose management, and lifestyle domains. Each item uses a 10-point response scale with higher scores corresponding to greater self-efficacy.21 Individual diabetes self-efficacy scores represent the mean value of all 8-items, therefore mean diabetes self-efficacy scores range from 1–10. A trained research assistant extracted clinical information, e.g., comorbidities, height, weight, and blood pressure, from patients’ medical records at the time of enrollment. HbA1c levels and a patient survey containing the diabetes self-efficacy measure were collected at baseline, at the conclusion of the active interventions (3-months) and one-year after enrollment. Study participants did not differ significantly in terms of age, race, and co-morbidity from the typical MEDVAMC primary care patient with diabetes.

Power and Statistical Analyses

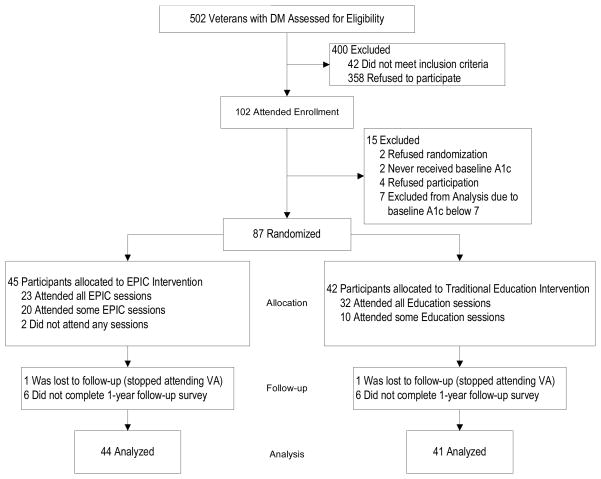

Our original power calculation called for 49 subjects in each group to identify a moderate effect size for between group reductions of HbA1c values (0.6% with standard deviation of 1.05) post- intervention assuming 80% power and 5% two-sided alpha. We anticipated minimal losses given the very low rate of attrition among primary care users of the VA system and regularity of HbA1c measurements. Our final study sample consists of 87 subjects due to exclusions at baseline (see Figure 2 for details) and the pilot design of the study limiting additional recruitment. Statistical analyses were 2-tailed with an αvalue of 0.05, performed using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS institute, Cary, North Carolina). We made comparisons between the EPIC and traditional education intervention groups at baseline using unpaired t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Unpaired t tests were also used to compare differences in diabetes self-efficacy scores by intervention group at 3-month and 1-year data collection points. We then used a mixed model approach to conduct separate repeated measures analyses for HbA1c and self-efficacy using the three time periods (baseline, 3-months and 1-year).23 The primary analysis accounted for the correlation of the HbA1c measurements within participants by fitting a line for each participant using all of their available data. The power to detect differences was maximized because participants were not removed from the longitudinal analyses if they were missing HbA1c values from only one of the three time periods. The independent variables that we included in the model consisted of time, treatment, and the interaction of time and treatment. The treatment effect measured differences between the EPIC and traditional education interventions at baseline, and the time effect measured whether there was an overall change in HbA1c values over time. The result of most interest in the repeated measures analysis is the time-by-treatment interaction. A significant value for this interaction would indicate that there was a difference between the two interventions over the full study time period (from baseline to 1-year data collection). A secondary longitudinal analysis was performed evaluating the role of diabetes self-efficacy as a factor mediating the relation of the EPIC intervention and HbA1c levels.24 The independent effect of self-efficacy on HbA1c values over time and the change in the time-by-treatment interaction variable are of most interest for this secondary mediation analysis.

Figure 2. Study design and participant flowchart.

EPIC indicates Empowering Patients in Care; VA Veterans Affairs.

RESULTS

Participants and Baseline Characteristics

Figure 2 shows the flow of participants through the study. Out of 502 patients who were screened for eligibility criteria and expressed interest, 102 potential participants attended an enrollment session. Among those attending the enrollment session, 4 subjects declined participation, 2 refused to be randomized and 2 subjects never received a baseline HbA1c measurement. An additional 7 participants who consented were excluded because their HbA1c at baseline were <7.0%. The final study sample of 87 participants completed informed consent and underwent randomization. Forty three (96%) of the 45 participants randomized to EPIC attended some or all of the intervention sessions and all 42 participants randomized to the traditional education group attended some or all of the intervention sessions. Only one person from each intervention group was lost to follow-up. These individuals had no post-intervention or one-year HbA1c measurements and could not be included in the final analytic sample. Diabetes self-efficacy data was available for 75 (86%) participants at 3-months and 76 (87%) participants at 1-year.

Participants in the EPIC and traditional education interventions were similar at baseline across a range of socio-demographic and clinical variables including HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, Body Mass Index, and duration of diabetes (Table 1). All participants were chronically treated diabetics with good access to primary care and diabetes education. Consistent with an older US Veteran population, the sample was overwhelmingly male, had multiple morbidities, and was of heterogeneous race. No differences were noted at baseline between the intervention groups in diabetes self-efficacy, knowledge and understanding of diabetes selfmanagement, and perceived general health status.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population by Intervention Group (N=87)

| EPIC Group Clinic Intervention | Traditional Diabetes Group Education | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, n | 45 | 42 | |

| Mean Age ± SD | 63.82 ± 7.9 | 63.45 ± 7.8 | 0.83 |

| African American race, n (%) | 15 (33.3) | 12 (28.6) | 0.63 |

| At least some College Education, n (%) | 31 (69) | 31 (74) | 0.61 |

| Lives Alone, n (%) | 11 (24) | 15 (36) | 0.25 |

| Years since diabetes diagnosis, mean ± SDα | 4.98 ± 3.1 | 5.04 ± 3.0 | 0.93 |

| Visits since enrollment in primary care, mean ± SD | 30.9 ± 15 | 37.0 ± 21 | 0.18 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mean ± SD | 8.86 ± 1.3 | 8.74 ± 1.2 | 0.66 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mean ± SD | 133.3 ± 15 | 133.6 ± 18 | 0.93 |

| Body Mass Index, mean ± SD | 33.4 ± 6.5 | 34.2 ± 6.7 | 0.62 |

| Deyo Comorbidity score, mean ± SD† | 3.2 ± 2.2 | 4.1 ± 3.0 | 0.16 |

| Perceived General Health Status, mean ± SD* | 2.49 ± 0.8 | 2.55 ± 1.0 | 0.77 |

| Understanding of Diabetes Self-Care, mean ± SD‡ | 2.98 ± 0.9 | 2.75 ± 0.9 | 0.25 |

| Prior Visits with Diabetes Educator, mean ± SD | 1.31 ± 0.71 | 1.25 ± 0.51 | 0.72 |

| Diabetes Self-Efficacy, mean ± SD¥ | 7.06 ± 1.98 | 6.64 ± 2.13 | 0.34 |

Comorbidity score derived from the Deyo modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index32

A single item that rates patients’ perceived health status along a four point scale, higher scores for higher self-rating.

Understanding of Diabetes Self-Care provides information on patients’ perceived knowledge and understanding of diabetes self-management. Individual scores are a mean of all 12 items from a subscale of the Diabetes Care Profile with a range of 1 to 5; higher scores corresponding to greater understanding.22

Diabetes Self-Efficacy scale is an 8 item measure evaluating respondents’ confidence in performing specific diabetes management tasks, such as diet, exercise, blood glucose management, and lifestyle domains. Reported results are a mean of all 8 items. Each item uses a 10-point response scale with higher scores corresponding to greater self-efficacy.21

Data collected from administrative records beginning in fiscal year 1998 to start of study using ICD-9 code of 250.xx

Outcome Measures

Significant differences between the two interventions were observed in HbA1c levels immediately following the active interventions (Table 2, top half), and the between group differences remained clinically and statistically significant at 1 year follow-up (Table 2, third row). Diabetes self-efficacy measures improved immediately after the intervention (3 month data collection) compared to baseline in both intervention groups (Table 2, bottom half). The selfefficacy measures at 3 months were significantly higher in the EPIC intervention compared with those in the education intervention (mean group difference= 0.84 ± 1.56, P=.02). Diabetes selfefficacy scores returned to baseline levels at the 1-year data collection, with modest (nonsignificant) between group differences (0.62 ± 1.94, P=.17).

Table 2.

Comparison of Hemoglobin A1c Level and Diabetes Self-Efficacy by Intervention Group at Each Study

| Outcome Measure and Study Time Point | EPIC Group Clinic Intervention | Traditional Diabetes Group Education | Between Group Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin A1c | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P |

| Baseline (n=87) | 8.86 | 1.3 | 8.74 | 1.2 | 0.12 | 1.25 | 0.66 |

| 3- month (n=85 | 8.04 | 1.35 | 8.70 | 1.38 | 0.67 | 1.36 | 0.03 |

| 1-year (n=85) | 8.05 | 1.40 | 8.64 | 1.39 | 0.59 | 1.39 | 0.05 |

|

| |||||||

| Diabetes Self-Efficacy | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Baseline (n=87) | 7.06 | 1.98 | 6.64 | 2.13 | 0.42 | 2.06 | .34 |

| 3-month (n=75) | 7.83 | 1.19 | 7.00 | 1.90 | 0.84 | 1.56 | .02 |

| 1-year (n=76) | 7.03 | 1.89 | 6.40 | 1.99 | 0.62 | 1.94 | .17 |

SD = standard deviation

Longitudinal differences in HbA1c levels across study time periods are illustrated in Figure 3 with a marked divergence between intervention groups at the 3-month data collection which held constant at the 1-year data collection. These observed longitudinal differences (Figure 3) are both clinically and statistically significant when considering the results of the repeated measures analysis for HbA1c levels. There was a statistically significant time-byintervention group interaction (F(2,85)= 3.55, P= .03) and a significant effect for time regardless of group (F(2,85)= 4.69, P= .01). The effect of treatment group alone was not significant (F(1,85)= 2.83, P= .10).

Figure 3. Longitudinal change in Hemoglobin A1c by intervention group.

Each data point represents the mean and standard error values for all patients (n=85) at each data collection time point. Using a repeated measures analysis, the overall effect of the interaction of intervention group by time was significant (F(2,85)= 3.55, P= .03) on longitudinal Hemoglobin A1c values.

A secondary repeated measures analysis was also performed to evaluate the mediation effect of diabetes self-efficacy on the primary outcome relationship of the time-by-treatment interaction and longitudinal differences in HbA1c levels. This analysis demonstrated significant effects for diabetes self-efficacy (F(1,85)= 10.39, P= .002). After adjusting for self-efficacy, the time-by-treatment interaction on longitudinal HbA1c values became non-significant (F(2,85)= 2.93, P= .059).

DISCUSSION

The results of this randomized comparative effectiveness study demonstrated that clinically significant improvements in HbA1c can be achieved after a three-month, four session group clinic intervention using the EPIC approach to self-management and medical care. The objective of EPIC was to promote collaborative development of goals and action-plans by participants and study clinicians. Action plans assist patients in integrating specific aspects of the diabetes treatment plan into everyday routines, increasing the likelihood of implementing lifestyle changes, adherence to medications, and performing home monitoring.8 Enhanced use of self-management likely produced HbA1c improvements post-intervention that were maintained over the year, given the corresponding changes in self-efficacy. EPIC participants were also trained to communicate their progress with an action plan and receive feedback from PCPs.9 These aspects of the intervention were less successful given the plateau in HbA1c improvements post-intervention. In contrast, the traditional education intervention participants had only modest and clinically insignificant improvements in HbA1c at both 3 months and 1 year. The group education sessions and the individual PCP follow-up rely on a traditional, cliniciancentric approach to diabetes self-management.25

The results of the current study add to the evidence supporting the effectiveness of group clinics for diabetes care.12–14;16 In particular, this study highlights the importance of organizing group clinics around theories of goal-setting19;26 and implementation of behavior change,10;27;28 given that prior studies with mixed results focused exclusively on how clinicians create treatment plans with comparatively little attention to how patients integrate effective treatments into everyday actions.17 Because diabetes action plans consist of a wide variety of behaviors, group clinic interventions should measure behavioral processes, like self-efficacy, that link clinical outcomes with self-management across heterogeneous action plans.17 Consistent with prior research, changes in self-efficacy among study participants correlated with effective goal-setting10 and with changes in HbA1c levels24 during and after the intervention. Furthermore, the longitudinal analysis adjusting for self-efficacy describes a classic mediation effect for diabetes self-efficacy in the relationship between EPIC intervention participation and improvements in HbA1c.23;24

The lack of ongoing improvements in HbA1c during the follow-up period is disappointing but consistent with prior literature. A meta-analysis of diabetes self-management interventions found an average HbA1c improvement of 0.76% post-intervention, but this effect declines over time to a minor improvement of 0.26% ≥4-months post-intervention.4 In contrast, EPIC participants maintained their 0.8% improvement 9-months post-intervention. Norris et al.4 also found that contact time with the diabetes educator was the best predictor of improvements in glycemic control. Furthermore, highly-effective lifestyle interventions for DM include considerably more intensive and prolonged contacts with participants.30 Booster EPIC sessions during the follow-up period may have produced additional improvements in HbA1c levels, which is supported by the finding that self-efficacy scores declined without booster sessions. Enhanced training and involvement of PCPs in the EPIC intervention may have also further improved HbA1c at follow-up. Training of study clinicians consisted of skills development for leading group sessions, mastery of study materials, and strategies for actively engaging patients in treatment planning25 (see appendix for details). The longitudinal success of EPIC will likely require dedicated training time and skills mastery by involved PCPs. In addition, PCPs must be self-aware of the difference between developing a treatment plan and collaborating with patients about the implementation of that plan into daily actions.25;27

Despite these important findings, the current study has limitations. Participation in the study was limited to older veterans receiving primary care in one regional Veterans medical center, which may limit the generalizability of these results. Future studies using a more diverse study sample may enhance the external validity of the EPIC intervention. The pilot nature of this study (sample size, funding, etc.) may contribute to measurement error and did limit our ability to track clinicians’ responses to action plans and PCPs’ post-intervention discussions with study participants; however the randomization of intervention assignment, persistence of the treatment effect at one-year and clinically meaningful effect size should lessen this concern. In addition, the study used a comparative effectiveness design in which the duration of the EPIC intervention sessions exceeded the length of instruction in the traditional groups. However, we note that, with the exception of content on setting goals and formulating action plans, the EPIC group received the same or less content about diabetes education than the traditional group. For example, the traditional group received instruction on details about following diabetic diets that the EPIC group did not. We feel that the extra time allotted to interaction among participants and collaborative work on goal setting more than made up for the relative paucity of content in the EPIC, compared to the traditional education intervention. The significant time and effort required by patients and clinicians to attend multiple two-hour group sessions over a threemonth time frame and the additional training required by study clinicians does limit the generalizability of the EPIC intervention.

Future studies involving the EPIC intervention should compare alternative methods of clinician-training and delivery of intervention content. Web and teleconference based training and group facilitation may increase the pool of clinicians skilled at group clinic facilitation and the EPIC approach to goal-setting. Adaptations to the EPIC design, such as the inclusion of booster sessions, may strengthen the effectiveness of the overall intervention by reinforcing self-efficacy gains and providing further refinement to participants’ action plans. Implementation studies are needed to identify alternative designs that facilitate wider dissemination of EPIC. Such studies could compare the four-session, group clinic model to group plus individual clinic sessions, group plus telephone support, and individual sessions using a “teamlet” model of primary care. Teamlets are the dyad of a PCP and a health educator/coach who performs many of the EPIC intervention activities before and after the PCP visit.31 The dyadic relationship fosters greater coherence between treatment plan development, setting of selfmanagement goals, and refinements to action plans over time. The dissemination of EPIC using group clinics, teamlets, or some combination will be muted without changes in health insurance financing.31 Increased support for medical homes and the passage of healthcare reform may provide the necessary catalyst.

Acknowledgments

The EPIC study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Centers for Research and Education on Therapeutics (CERTs) (U18HS016093, PI: Suarez-Almazor). Additional support for the EPIC study was provided by a Clinical Scientist Development Award from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (PI: Naik). Dr. Naik received additional supported from the National Institute of Aging (K23AG027144) and the Houston Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence (HFP90-020) at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

We deeply appreciate Elisa Rodriguez and Andrea Price for the time and effort they put into intervention management, patient recruitment and retention, and data collection. Special thanks to Donna Rochen, PhD for her expertise in intervention recruitment and study procedures, and Annette Walder, MS for managing the study database and running preliminary analyses.

APPENDIX

EPIC Intervention Description

Once participants were randomized to either the EPIC or traditional educational interventions, research personnel assigned them to cohesive groups of 5 to 7 members. Membership in a group was consistent for the full intervention period for both the EPIC and traditional education interventions.

The EPIC intervention groups met once every three weeks for four sessions, covering the three-month time span. All sessions were structured to a one-hour group session format, broken down into three components. They began with a 20-minute didactic discussion pertaining to the topic of the session, followed by a 20-minute problem-based group discussion, and then a 20-minute group discussion about personalizing the topic into one’s daily routine. After the group session, the participants took turns meeting with the study clinician individually for 10 minutes each. Meanwhile, participants were encouraged to discuss the relevant session topic with each other. Peer discussions helped to prime individual discussion with the study clinician. Each of the four EPIC intervention sessions focused on a particular theme related to diabetes self-management and used materials contained within a workbook given to all participants at the start of the first session. Sessions were organized along the following order and content.

Session 1, the Diabetes ABCs

This initial session focused on teaching participants the importance of monitoring their Hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels. The session began with a 20 minute clinician-led discussion starting with introductions, elicitation of participants’ expectations for the intervention, and brief descriptions of all four sessions. The study clinician encouraged participants to describe their goals for their overall health and their diabetes-related concerns, e.g., health risks, anxieties directed at treatment outcomes, expectations of care, etc. Next, the clinician led a 20 minute problem-based group discussion about the patient’s role in monitoring the control of their diabetes. The Diabetes ABCs were introduced, specifically how changes in the ABCs impact overall health. Session handouts (from the participants’ workbook) included the diabetes “forecast”--a form relating diabetes control status to a weather forecast. The diabetes forecast gave context for clinicians to illustrate how the levels of particular Diabetes ABCs relate to future health risks. Case examples of patients (with sunny, partly sunny, and stormy forecasts of diabetes control) were introduced and reviewed to convey the link between patient’s health behaviors and their level of diabetes control and future health risks. The final 20 minute discussion transitioned to each participant’s individual case using the forecasts. Participants then set a personal goal for their diabetes HbA1c level, which served as a framework for guiding goal setting in the subsequent session. Peer discussions focused on comparisons of participants’ current forecasts, prior levels of diabetes control, and ideas about how to improve forecasts.

The group discussions were followed by the one-on-one discussion with the study clinician. Clinicians reviewed the treatment plan described in the medical record by the patient’s PCP, and elicited patients’ experiences implementing the treatment plan into their daily lives. Participants discussed their preferences for lifestyle changes and home monitoring behaviors, and their perceptions of and adherence to medication regimens. Study clinicians integrated this information into collaborative goals with participants. These goals and action plans were then placed in the medical record so PCPs could review results as well. In cases where participants were experiencing adverse events or side effects to medications, study clinicians could change a medication type or dose and inform the PCP with an electronic alert.

Session 2, How to make Diabetes Goals and Action Plans

The purpose of this session was to expose participants to the basics of goal-setting theory and assist them in developing discrete action plans to achieve their broader diabetes goals. Clinicians spent the first 20 minutes of the group describing the characteristics of a high versus low quality goal. Discussion of goal-setting theory was kept succinct and guided by the participants’ workbook to ensure that everyone could easily grasp the key points. Adherence to the following principles increases the chances of goal achievement, and thus, positive health outcomes:18;19

High quality goals are specific with measurable steps that help to track progress and goal achievement. Avoid vague or ambiguous goals that do not lead to goal attainment.

High quality goals are challenging yet realistic. Challenging goals motivate participants to work harder toward goal accomplishment, but avoid setting unreachable standards.

Setting deadlines for goal achievement is recommended. There should be both short and long term deadlines with opportunities for reflection and feedback regarding progress.

In the 20 minutes following the educational lecture, participants reviewed case examples of diabetes goals and action plans. Through peer discussion, they rated the quality of the goals in the case examples and their likelihood of improving overall diabetes control. The last 20 minutes of group discussion involved completion of an action plan worksheet. Worksheets guided participants in the process of setting individualized, high quality goals and action steps. These worksheets were reviewed by the group to ensure that each goal met the criteria described above.

During the one-on-one discussion, clinicians challenged participants to reshape their PCP’s treatment plan into a set of diabetes goals, each with an action plan. In most cases, goals focused primarily on diet and exercise changes, home monitoring of blood sugar and medication effects, and communication with PCPs about medication effects. Patients also developed goals about sleep, pain, and other barriers to diabetes self-management. In addition, medication regimens were revisited in such a way that medication adherence and monitoring were adapted into goals and action plans. Clinicians could recommend changes to medication types and dosages, and responses to those recommendations were driven by each participant. Participants either developed action plans to discuss changes with their PCP or collaboratively set an alternative medication action plan with the study clinician. In both cases, study clinicians sent a research note to the PCP along with an alert if the medication regimen was changed.

Session 3, How to Talk to Your Doctor

This session emphasized the importance of effective doctor-patient communication, and encouraged participants’ active involvement during clinical encounters. Sessions began with a 20-minute segment in which participants viewed a video of an idealized doctor-patient encounter. Following the video, participants identified the specific communication elements within the encounter that made it effective. The study clinician encouraged participants to 1) ask questions to become better informed about the treatment plan and positive and negative outcomes of recommended treatments; 2) be prepared for their visit by setting goals for the encounter, knowing their medical history, writing down topics they want to discuss, taking notes during the visit, sharing all relevant information, prioritizing needs, and having a family member or friend present to listen to the conversation; and 3) communicate their health concerns to their clinicians, including expressing their preferences, beliefs about a healthy lifestyle, and questions concerning medications and side effects.20 For the 20 minute case discussion, participants were given “tip cards” describing these doctor-patient communication principles. Participants discussed their experiences using elements from the tip card with clinicians. In the final 20- minute group discussion, participants made a communication action plan guided by the tip cards and peer discussions. Again, following the group session, one-on-one discussion between participants and the group clinician were conducted for 10 minutes each. Study clinicians reviewed participants’ progress with their goals and action plans, and assisted participants in making refinements to action plans. Goals and action plans in this session focused on the full spectrum of diabetes self-management including barriers and facilitators of action plan success. In particular, action plans related to communicating with PCPs about self-management were developed.

Session 4, Action Plan Feedback & Review

The objective of this session was to reinforce and integrate the points delivered during the three prior sessions. Participants assessed their individual progress toward goal achievement through peer and clinician delivered feedback. The 20-minute didactic portion of the session recapitulated the topics of the three prior sessions to strengthen participants’ grasps of the important concepts and clear up any remaining questions. For the case based 20-minute group discussion, participants were asked to write down their current diabetes goal and action plans with particular attention to goal quality. Discussion then focused on peer evaluation of goals and action plans, especially their expectations that goal attainment would lead to improvements in personal Diabetes ABCs Forecasts. During the final 20 minutes, participants were encouraged to schedule a future appointment with their PCP to review progress towards diabetes goals and receive feedback on action plans. Participants received a “treatment plan” form intended to facilitate shared decision-making about diabetes goals with PCPs. The treatment plan form used the same formatting as the worksheets in session 2 that guided the development of action plans. Participants placed all their active diabetes goals and action plans onto this treatment plan form after receiving peers’ comments.

During the final one-on-one consultation, study clinicians provided participants with feedback on the self-management goals and action plans described on the treatment plan form. Study clinicians sent a research note to all PCPs describing the final self-management goals and action plans articulated by patients.

Training of Study Clinicians for EPIC Intervention

Training of study clinicians consisted of 1) a discussion introducing the objectives and approach of the EPIC intervention, 2) review of the contents of the participants’ workbook used to facilitate peer discussion, and 3) running a pilot group clinic session and receiving feedback from an experienced group clinician. Study clinicians were introduced to the EPIC study method and objectives by contrasting the typical clinician-centric approach to self-management with a patient-centered or patient empowerment approach to self-management.25 This seems like common-sense, but is often overlooked by potential clinicians. The oversight is explained by the fact that most clinicians do not understand why titrating medications does not correlate directly with improved diabetes care.25 EPIC is based on the premise that self-management is a means to integrate medical treatment plans with patients’ goals, and then adapt those goals into everyday action plans. In this way, self-management ensures patients’ mastery of the principles of diabetes care, implementation of collaboratively set treatments, communication of challenges, receptiveness to feedback, and eventually the initiative to adapt action plans without excessive assistance. Once patients are willing participants in this process, changes in medications (along with lifestyle changes and home self-monitoring) can result in better diabetes outcomes.28 Next, training of clinicians involved walking through the materials contained in the intervention workbook. Particular attention was paid to empiric evidence defining high quality goal-setting and its association with goal-attainment,18;19 as well as the evidence linking effective doctor-patient communication and improved health outcomes 9;20

For the final training step, study clinicians led a “pilot” group session with clinic patients followed by a de-briefing to review strengths and weaknesses of the clinician. Comments to novice clinicians centered on 1) facilitating group discussion and 2) eliciting personal experiences of participants. These skills encouraged patients’ active mastery of the study objectives instead of relying on a passive classroom approach. Clinicians were ready to lead a session once they achieved a strong grasp of the intervention workbook and became comfortable leading a group clinic session.

Reference List

- 1.Centers for Disease Control. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States 2007. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers of Disease Control an Prevention; 2008. pp. 7–1–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:725–731. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2269–2276. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1159–1171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288:1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parchman ML, Zeber JE, Palmer RF. Participatory Decision Making, Patient Activation, Medication Adherence, and Intermediate Clinical Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: ASTARNet Study. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:410–417. doi: 10.1370/afm.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorig K. Action Planning: A Call To Action. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:324–325. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naik AD, Kallen MA, Walder A, Street RL., Jr Improving hypertension control in diabetes mellitus: the effects of collaborative and proactive health communication. Circulation. 2008;117:1361–1368. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.724005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodenheimer T, Handley MA. Goal-setting for behavior change in primary care: an exploration and status report. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rickheim PL, Weaver TW, Flader JL, Kendall DM. Assessment of group versus individual diabetes education: a randomized study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:269–274. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman EA, Eilertsen TB, Kramer AM, Magid DJ, Beck A, Conner D. Reducing emergency visits in older adults with chronic illness. A randomized, controlled trial of group visits. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trento M, Passera P, Tomalino M, et al. Group visits improve metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:995–1000. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadur CN, Moline N, Costa M, et al. Diabetes management in a health maintenance organization. Efficacy of care management using cluster visits. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:2011–2017. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.12.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clancy DE, Huang P, Okonofua E, Yeager D, Magruder KM. Group visits: promoting adherence to diabetes guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:620–624. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0150-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edelman D, Fredrickson SK, Melnyk SD, et al. Medical clinics versus usual care for patients with both diabetes and hypertension: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:689–696. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sikon A, Bronson DL. Shared medical appointments: challenges and opportunities. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:745–746. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strecher VJ, Seijts GH, Kok GJ, et al. Goal Setting as a Strategy for Health Behavior Change. Health Educ Behav. 1995;22:190–200. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. A 35–year odyssey. Am Psychol. 2002;57:705–717. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;74:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39:1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzgerald JT, Davis WK, Connell CM, Hess GE, Funnell MM, Hiss RG. Development and Validation of the Diabetes Care Profile. Eval Health Prof. 1996;19:208–230. doi: 10.1177/016327879601900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twisk JW. Applied longitudinal data analysis for epidemiology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston-Brooks CH, Lewis MA, Garg S. Self-efficacy impacts self-care and HbA1c in young adults with Type I diabetes. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:43–51. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson RM, Funnell MM. Patient empowerment: myths and misconceptions. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;79:277–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oettinger G, Gollwitzer PM. Goal-Setting and Goal-Striving. In: Brewer MB, Hewstone M, editors. Emotion and Motivation. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2004. pp. 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naik AD, Schulman-Green D, McCorkle R, Bradley EH, Bogardus ST., Jr Will older persons and their clinicians use a shared decision-making instrument? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:640–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeWalt DA, Davis TC, Wallace AS, et al. Goal setting in diabetes self-management: taking the baby steps to success. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wing RR The LookAHEAD Reseach Group. Long-terms effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Four-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170:1566–75. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen EH, Thom DH, Hessler DM, et al. Using the Teamlet Model to Improve Chronic Care in an Academic Primary Care Practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:S610–4. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1390-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9- CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]