Abstract

Using qualitative data collected from a sample of rural-urban migrants over the age of 15 in two Nairobi slums interviewed in 2008, this paper discusses the migrants’ extent of satisfaction with their residential location and decision to migrate. The study sheds light on why people continue to migrate to, and stay in, the rapidly growing slum settlements despite the high levels of poverty and poor health conditions in these areas. Tenure status is related to satisfaction for all ages. Environmental factors were frequently mentioned as a source of dissatisfaction. Life cycle and ‘age-cohort effects’ may also affect satisfaction for different age groups in terms of who is satisfied as well as the issues that are considered for satisfaction. High levels of dissatisfaction with slum life may be responsible for high out-migration in slum areas, although it does not mean that those who remain do so because they are satisfied. At the same time, challenges associated with slum life do not automatically signify dissatisfaction. Perceived success, as well as conditions in the area of origin can be used to explain and understand satisfaction/dissatisfaction with slum life. Satisfaction with migration and residential location may be related not only to the destination place, but also to events in the area of origin.

Keywords: Migration, Slums, Urban

Introduction

Studies on satisfaction with migration have focused on international migrants in developed countries and the implications of discrimination that many migrants experience in host countries.1 Limited research has been done on migrants’ satisfaction in developing countries.2 Most studies on migration in Africa have used quantitative data to understand reasons why people migrate from one place to another and the type and amount of monetary transfers that they make to their places of origin.3–11 Migration to cities has been primarily attributed to better economic opportunities and lifestyles in cities compared to rural areas, and to cataclysmic events such as famine and war.12,13 Naturally, one would expect push and pull factors to play a major role in migrants’ assessment of the success or failure of their migration. Cultural adaptation theorists note that those with “high push motivation” may have problems adapting to their new community, while migrants who are highly proactive in making migration decisions may be disappointed if their high expectations are not met.14 For example, where economic factors predominate as motivators for rural-urban migration, the ability to get a job or improved economic conditions may increase the migrant’s satisfaction, while failure to get a job or improve economic conditions may have the opposite effect.15 However, people who are forced to migrate because of war or civil strife may feel reasonably satisfied even in tough economic conditions as long as there is peace at the destination location.16

Studies in developed countries have found a significant relationship between satisfaction and future migration intentions, with those who are not satisfied with their current life more likely to express a desire to move and to actually move in the near future.17–20 Community facilities and resources may determine migrants’ satisfaction, with migrants who have access to such facilities more likely to be satisfied than those who do not have such access.21 These studies have shown that dissatisfaction with migration or poor quality of life diminishes the length of stay of migrants in host communities. In developing countries, however, because of lack of economic and related options and opportunities, dissatisfied migrants may not be able to move even if they want to. This issue is particularly critical for understanding satisfaction with migration and residential location for rural-urban migrants in urban slum settlements, characterized by high levels of unemployment and underemployment, as well as poor health and environmental conditions.22,23

In economically deprived settings, it is not evident what entails success or whether it is success or failure that prolongs duration of stay for migrants. Unhappy migrants may not be able to out-migrate if they have no other affordable place to go to.24 Those who are successful economically may stay longer if they want to take advantage of cheap rent in slum settlements and generate savings for future investments or buy property there. Others may choose to leave the slums as soon as they can afford better living conditions elsewhere. “Tied” migrants such as wives and children may be more likely to be dissatisfied than independent migrants because they did not drive or make the decision to move.25,26

Assessment of success and reasons for dissatisfaction can be mediated by age (life cycle), gender of person, perception of success, expectations at the time of migration, and one’s assessment of the potential or capacity of the host area to meet one’s goals and expectations in future. For example, some studies have shown that the life cycle or “age cohort effect” may have differential impact on satisfaction for migrants depending.16,27,28 Older people, who are likely to have had a more traditional upbringing may not be willing to question the status quo. At the same time, future chances of change are limited with increasing age and therefore elderly people may express more satisfaction with their decisions and current place of residence than young people.29 The length of stay of residents has also been shown to be important in explaining satisfaction although there is no agreement on the direction and nature of relationship with some predicting a positive relationship while others find no relationship.30,31 Staying away from a place of origin for a long period may also reduce chances of returning, especially for the unsuccessful migrants, who may be reluctant to go back as failures or in worse shape than they were when they migrated; and thus, they become trapped in the slum.

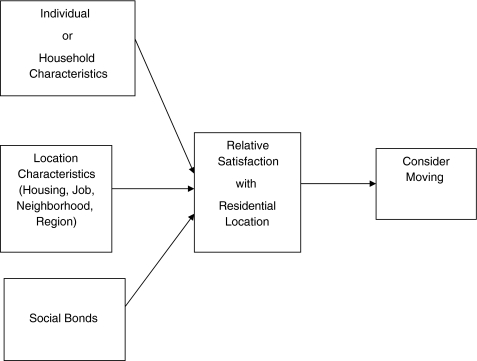

This paper borrows from the first stage of Speare’s two-stage stress threshold model of mobility, which recognizes individual/household characteristics, location characteristics, and social bonds as important factors in explaining residential satisfaction.32,33 We focus on individual and location characteristics. Speare regards satisfaction as an intervening variable between individual/background factors and mobility.32 Individual/household factors include factors such as age, income, duration of residence whilst location characteristics may include housing characteristics, location of neighborhood in relation to job prospects, neighborhood characteristics, and region.32 While satisfaction is related to expectations, dissatisfaction may result from changes in household needs, deteriorating amenities, changes in aspirations due to social mobility, or having knowledge of better opportunities elsewhere. Figure 1 presents the first stage of the Speare residential satisfaction model.

FIGURE 1.

Speare’s model of the first stage of mobility decision making: the determinants of who considers moving (source).34

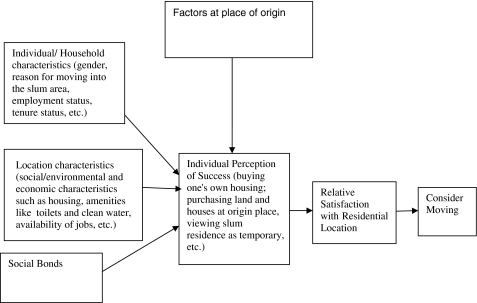

The model further states that there is a certain threshold of dissatisfaction at which an individual may start considering moving. On the other hand, a satisfied person is less likely to move even if by moving elsewhere his life can become even better. Figure 2 presents an adaptation of the Speare model.

FIGURE 2.

Adapted model explaining satisfaction for migrants.

For our purposes, we posit that there is no direct link between satisfaction and background factors such as individual and household characteristics. Rather, individual perception of success or failure determines whether a person is satisfied or not. At the same time, factors at origin place may influence whether a person regards themselves as successful or not, consequently impacting satisfaction. We will also borrow from the cultural adaptation theories which recognize that migrants may go through different stages of cultural adaptation where they assimilate into the host society and change their norms, values, and behaviors. Some of those who fail to adapt may opt to return to their places of origin, move to other destinations, or continue to reside in the host societies even though they are unhappy because they hope things will improve later.14,34

Cities and other urban centers in Africa are growing at unprecedented rates and slums are providing housing to the majority of urban dwellers in the region.23 Slum residents have worse health outcomes compared to other population sub-groups.35 If these trends continue, slum residents will constitute increasing proportions of national populations and influence national indicators in health and other development issues. Therefore, it is important to understand migration patterns and dynamics for slum residents. This paper addresses several gaps in literature on migration in slum areas. By examining why they came to the slum settlements, the study helps clarify why people continue to flock to slum settlements (despite the poor living conditions there). Examining satisfaction with residential location would clarify the nature of challenges that slum dwellers face, what factors make people stay longer or leave slum settlements (which have been largely ignored by migration scholars in Africa), and the extent to which slum residents consider slum areas as transitory or long-term settlements.

Data and Methodology

This paper is based on qualitative data collected from Korogocho and Viwandani slum settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. The data comes from a qualitative migration study nested onto the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS), a longitudinal study implemented by the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) in the two slum communities since 2000. The NUHDSS involves regular visits to every household in the study areas once every 4 months and covers about 72,000 people in about 28,000 households every year. The qualitative study was part of a 5-year research program designed to investigate linkages between migration, poverty, and key health outcomes at important stages of the life cycle, namely: childhood, adolescences, adulthood (postpartum maternal health), and old age. The qualitative migration study investigated the reasons and motivations for migrating, migrants’ experiences in the city, whether people perceive themselves as failed or successful migrants, as well as any social networks they may maintain in both the urban and rural areas.

Using in-depth interviews (IDIs), the study interviewed 97 individuals aged 15 and above, who were randomly selected from the NUHDSS database to represent equal numbers of men and women in the following five age categories: 15–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50+. The selection procedures followed the life course approach in order to examine differences in aspects of migration across the life course. The study was designed to recruit 20 respondents in each age category but failed to contact three of the sampled respondents.

All IDIs were carried out in the Swahili language and tape recorded. The tapes were transcribed and translated verbatim into English. After reading the transcripts, the interviews were then coded, paying attention to emerging themes using NVIVO 8, software used in the analysis of qualitative data. This paper is a result of analysis of the theme focusing on satisfaction of migrants. We use the term satisfaction to understand whether migrants are relatively satisfied with their decision to migrate and their current residential location.

Context

Korogocho and Viwandani are two of Nairobi City’s numerous (40+) slum settlements, which are estimated to house over half of the city’s population of more than 3 million people. Korogocho was officially settled in December 1978 and covers an area of about 49.2 ha. It is located about 12 km from Nairobi’s city center. To the east and south east of the slum settlement is the Nairobi Refuse Dump site where some Korogocho residents make a living by scavenging for food or salable materials like plastics and scrap metal. Korogocho developed on a mix of property originally owned by an individual named Baba Dogo and reserve land left by the City Council on the banks of the Nairobi and Gitathuru rivers. Houses in Korogocho are mostly made of mud or timber, with roofing composed of tin waste. Most of the residents of Korogocho are either uneducated or dropped out of school at the primary level; only 19% of men and 12% of women attained a secondary education.

Viwandani, officially recognized as a settlement in 1973, covers an area about 3 km long by 1 km wide. It is located about 7 km from the Nairobi city center. It developed on reserve land left by the City Council on the banks of the Nairobi river. To the north of the settlement are the industries where many Viwandani residents earn a living by working in the factories. The presence of industries explains why there are more men in the economically active group in Viwandani compared to Korogocho. However, it is clear that the majority of Viwandani and Korogocho migrants (close to 97%) are migrants who came from rural areas to seek employment and other opportunities in Nairobi city.36 Lack of jobs, proper housing, and affordable water supplies are prevalent in Nairobi’s slum areas, including Korogocho and Viwandani.35

Quantitative data from the NUHDSS show that females are more likely to out-migrate than males at age groups 15–19. However, movement out of the Demographic Surveillance Area (DSA) is higher among males aged 60 and above. In both settlements, half of the residents have lived in the slums for 10 years or more.37

Results

The first part of the results section will focus on economic reasons that are related to satisfaction and dissatisfaction and the second part will focus on social and environmental reasons.

Economic/Individual Reasons

Satisfaction is related to progress or perceived progress and performance at the economic level. For migrants who came to the slums for purely economic reasons, satisfaction largely depended on whether or not they thought they had succeeded their economic goals. The respondents below clearly summarize issues that can lead to either satisfaction or dissatisfaction with migration:

I can finish a whole month without being able to raise rent for this place and have to negotiate with the landlord not to throw me out. What I get is enough for food only. Business is not doing well and everything is very expensive. I would describe people living here as those who are surviving purely by luck. They live from day to day. When it comes to living conditions it is quite hard, here I am living with my son and my grandchildren. There is no freedom at all. God did not create a human to live like the way we are living here. (Never-married female, 63 years old, Korogocho.)

After being asked if he was satisfied with life in the slum area or would have preferred to live in the rural areas, another respondent said:

....People go to live upcountry [in a rural village] because of problems. But if you are settled, why would you want to go upcountry, to do what? There is only one day that one goes home, that is your burial day. (Married male landlord, 62 years old, Korogocho.)

The ability to purchase property in the slum or elsewhere was a source of satisfaction for migrants. Those who owned houses were satisfied because they did not pay rent, and in addition they could get rent from tenants. People who owned property did not usually express a desire to move out. The only landlord in the sample said he would not consider living in the rural areas since he had to stay in the slum to manage his properties. He feared that if he moved to the rural areas, his tenants might start defaulting on rentals and he could eventually lose his properties. People who said they were satisfied often pointed to the ability to pay rent, send children to school, and the availability of cheaper food, but frequently also stated that they would prefer to live somewhere else if they had more money. Perceived progress in these areas would lead respondents to say they were satisfied even though they also pointed out that they were not happy with other conditions in the slum. However, even if migrants were unhappy with the conditions in the slum, they hoped that things would improve and that they would “persevere” until reaching their economic target.

A close reading of the transcripts revealed that those aged between 30 and 49 years were more likely than other age groups to be dissatisfied and frustrated for economic reasons than other age groups. Some respondents were disappointed because they had lost all hope of moving out after initially thinking the slum would be simply a transitory place on the way to better lives and better neighborhoods. Others thought they would make enough money to invest in their rural homes, as shown by the excerpt below:

Interviewer: Are you satisfied with your decision to move to Nairobi?

Respondent: Not really. I didn’t achieve what I really wanted in my life. I would like to construct my own house, and then keep dairy and poultry upcountry... that is where I want to do all these developments.... [When I came here] I thought if there would be enough money, then I would go back to the rural area and make a home there.

Interviewer: And none of it has happened?

Respondent: No. (Female housewife, 32 years old, Viwandani.)

Their hopes had been shattered, hence the dissatisfaction with their living situations. Lack of job opportunities were the main source of dissatisfaction with slum dwellers’ decisions to migrate to the city. Some of the economic reasons for satisfaction may be relative to the migrant’s previous situation: even if economic prospects in the city were not ideal, migrants were likely to say they were satisfied if conditions were better than in their area of origin. While acknowledging the difficult slum conditions, some people said they were satisfied because their income levels had improved since migration and they were living independently with the ability to make their own decisions on a lot of things.

Things are better than they were before. I have an income which is helping me to sustain myself, my mother and the children… Now I can do my own things at my own pace without any interference. I can take care of myself without having to depend on anyone. I would say I am satisfied. The children are well fed and their school needs are comfortably met. (Single, female banana seller, 35 years old, Korogocho.)

In spite of the fact that many people who come to the city have difficulty finding stable and well-paying livelihood activities, people keep moving to the city from rural areas because of misconceptions of what the city can offer, as shown by the following excerpts:

It is hard to convince someone that Nairobi is not the best place. Sincerely speaking, you will find some people who are really suffering because they cannot meet their needs with the meager salary they are getting. (Married female, 47 years old, Viwandani.)

I used to hear that when you come to Nairobi there are many jobs. Whenever people were coming from Nairobi, they used to construct houses and make their homesteads beautiful. We admired that and we felt that by coming to Nairobi, things will be good... [and that has not happened]. (Married male, 28 years old, Korogocho.)

Past experiences and economic success of people who lived in Nairobi continue to influence many people to migrate to the city. Potential migrants and their communities remember the success stories of those who migrated before. Those regarded as failed migrants are ignored, or failure is attributed to individual traits like “not working hard enough.” Thus, when migrants move to the city and are confronted by a different reality, dissatisfaction may arise. In fact, many people alluded to the fact that they would not actively encourage anyone to migrate to the slum settlements in case the migrants become disillusioned and blamed them for inviting them. When asked why he would advise people not to migrate to Nairobi when he himself was a migrant, one respond said the following:

I will tell him I didn’t have a choice at that time. I didn’t have anyone to ask for advice and... it is now that [jobs] are picking up in the rural areas. I have now realized Nairobi is not as juicy as people make it to be... Problems in the slum are many. We are not happy living here. Because our source of income is limited, I am forced to live here with my family... I am not satisfied. Had it been possible, I would have gone back to settle at the rural home.... The source of income is weakening by the day. There are no jobs at the moment. (Male respondent, 28 years old, Korogocho.)

Many respondents mentioned that they would not encourage anyone to come and settle in the slum areas unless they had no alternative means of survival elsewhere. Some of the reasons cited as causing dissatisfaction had nothing to do with the intrinsic nature of the slum itself, but with the general economic climate characterized by a poorly performing economy. Some migrants also cited declining economic conditions as a reason for dissatisfaction, as life was more difficult than before, food more expensive, and jobs hard to come by or lowly paid.

Those who encouraged others to migrate from rural areas into the slum often viewed the slum area as a “transit place.” Asked about his life in Korogocho, one respondent who had regarded the slum as a transit place said:

There are many other things I have not accomplished. I don’t see any light at the end of the tunnel at all. I didn’t think by now I would still be living in Korogocho. Since 1998, that is almost ten years and there is no change. I have not moved an inch. (Male respondent who joined into conversation with informant, unknown age, Korogocho.)

Thus, in spite of the problems people may still continue to live in slum areas with the expectation that they would jump onto the “escalator” one day. Getting a job would improve their lives since they would get a minimum level of resources needed to develop and move up or out of the slum areas.

Location Characteristics: Social and Environmental Reasons

The poor environmental conditions in the slum settlements were a major source of concern and dissatisfaction for the residents. Lack of social amenities and a decaying slum environment were frequently mentioned as making life in the slum difficult and unsatisfactory.

If I had money, I would not live in Korogocho. Life in Korogocho is hard and once you get into a house, you have to buy polythene paper to cover the floor and walls. Life here is pathetic. (Married female, 28 years old, Korogocho.)

Life here is terrible; there are some things that I don’t enjoy. There are no toilets: you have to do it in the house and throw it [away in a plastic bag.] (Male respondent, 17 years old, Korogocho.)

Those who expressed environmental dissatisfaction usually expressed a desire to move out and use very highly emotive phrases like “I hate this place,” “this place is pathetic,” “this place is not fit for humans.” The respondents sounded helpless as they felt they could not change the slum environment and they did not expect the government to change it either because slums are illegal settlements. But they decided to persevere and continue living in the slums because they hoped that they could one day get a good job and make it out of the slums.

Reasons for satisfaction also varied in terms of age group and gender of person. Among those aged 50 and above, a common thread in all interviews was their strong desire to go and live in rural areas. Their concerns revolved around lack of space and other amenities in the slums. However, despite these concerns, most of them pointed out that they could not afford to go to their rural homes. Older women were generally more likely to be satisfied than younger women. Younger women mostly argued that the environment was not clean and not conducive for raising children.

Those aged between 15 and 19 were more likely to be satisfied if they were attending school. Many of those below the age of 19 pointed out they were satisfied as they were still going to school and therefore did not see any need to out-migrate, as the excerpt below shows:

I am satisfied and do not have any problem and I am attending school, which was my main problem. (Male student in form 2, 18 years old, Korogocho.)

Most female migrants who came to the city pushed by unhappy marriages were generally happy in spite of the fact that they admitted to living a hard life. For instance, a 57-year-old female who migrated to Nairobi at 20 and left her husband, who had subsequently remarried, admitted that although her life was hard economically, she was more satisfied in Nairobi because she was living a free life and no one harassed her. Many older women who were divorced reported that they were satisfied since they had independence, as the excerpt below shows:

I would say I am satisfied because I managed to educate my children... nobody has interfered with me, no one has stolen from me or beaten me, and no misfortune has befallen me. (Never-married female, 63 years old, Korogocho.)

Many of the single older women were also more likely to see themselves living in the slum settlements forever because they could not make enough money to go to non-slum parts of the city. The older women were also less inclined to contemplate going back to their rural homes where they did not own any land, which is traditionally given to sons and not daughters.

Often, women were dissatisfied with the living conditions in the slums but could not move away because of family. Some women were unhappy because they did not have much say on the decision to move to the slums or to move out; such decisions are often made by husbands or other male guardians or relatives for single young women. A young woman who had been working as a secretary outside of Nairobi had to move to stay with her mother.

You know you can only be happy with the life you are leading at that moment.... I cannot recommend to anyone to come and live here, whether I know them or not. This is not a place to live: only as a last option should anyone be forced to live in such conditions.... I only moved to satisfy my family, not me personally, so I am not satisfied. You know I am already grown up and would like to live my own life. But since they are happy, I have no choice but to follow suit and try my level best to be happy with what I have until God decides otherwise. (Single female, 26 years old, Korogocho.)

Some women who preferred to live in the rural areas could not do so because their husbands did not earn enough in Nairobi to support split families. When asked if she was satisfied with her life in Viwandani, one woman who had moved to follow her husband expressed that she would have preferred to live in rural areas but had to do what her husband wanted:

If I had the resources, life would be different. If he had a better income, I would be living a better life. I would like my husband to get a better salary so that I can live at my rural home. When he sends me some money at the rural home, I will be able to do some other improvements and developments in the rural area. When I am here I am very idle and that is not good for me... At the same time I don’t know what my husband has in mind. If he says no you have to wait a little longer, that is what I will do. It is good to obey sometimes…he is the one with authority over everything right now. I have to go by his word. (Female respondent, 29 years old, Viwandani.)

From the above quotations, it is clear that some women who migrated to follow their husbands, or for other family reasons where they did not actively take part in the decision, were not happy.

Talking about the difficulties of living in an informal settlement, one 57-year-old migrant woman said, “Many people would not be able to live the kind of life I am leading.” Other respondents echoed the same view, as noted in the excerpts below:

First we don’t have toilet facilities and if they come and see this stagnant water.... I cannot agree for someone to come here and live in these pathetic conditions. (Married, female petty trader, 23 years old, Viwandani.)

This place is a health hazard. There are trenches of dirty water and waste from the industries.... The toilets are mud walled and the floor. It takes time to get used to it. (Female respondent in her 20s, Viwandani.)

The pathetic conditions that migrants referred to included a general lack of amenities such as toilets, good housing, clean water, and good schools for children to attend.

“We May Not Like it here but We Have Got to Stay”

Some respondents in the sample said that people they had assisted with coming to Nairobi had not been able to cope with slum conditions and had migrated back to the rural area. There are also many migrants who may choose to stay regardless of whether they are happy or not. Some respondents did not regard moving out of the slum as a viable alternative and used the term “forced” to indicate why they were staying in the slum areas where they had to struggle to make ends meet:

It is not a question of satisfaction, but circumstances force you to live where you can afford these days and that is what most people are doing. They are forced to live lives that are not the best but accept it because they do not have a choice. (Husband of a key respondent who arrived and joined the conversation in the middle of the interview session, unknown age, Korogocho.)

There are people like me, who lived in an estate before and because of financial challenges, I had to move to this area… The only people who long to move out are people like me who were forced by financial constraints to move to the the slum. (Male respondent, 32 years old, Viwandani.)

It emerged in many interviews that a lack of viable alternatives does “force” people to stay in the slum settlement. Many respondents also exhibited hopelessness and despair that things would never change. Other migrants have managed to stay by normalizing the slum condition. Such respondents highlighted that living in slums was not such a bad thing after all, since the problems they experienced like the dirty environment, lack of toilets, and insecurity were being experienced by other people in the communities:

I am satisfied. Life is ok. We are living well, it is also good to try and feel satisfied with what you can afford… God willing, if we get money we will definitely move to another place. Life is hard here. I would prefer upcountry... (Married female, 25 years old, Viwandani.)

I have not encountered anything out of the normal because life is the way you take it.... People go through the same problems that I am facing, so there is nothing abnormal here. (Female respondent, 30 years old, Korogocho.)

No, I don’t regret [the decision to come and live here]. I am satisfied in the sense that I am not the only victim here but we are many people struggling to make ends meet. We have decided to accept things the way they are so that we can have some peace of mind. I can’t say I am satisfied... (Husband of key respondent, unknown age, Korogocho.)

Thus, accepting the slum condition as the normal condition has helped dissatisfied migrants to deal with their situation and “persevere”.

Conclusion and Discussion

Using the individual/economic and location/social environment characteristics in Speare’s model, this paper sought to understand residential satisfaction among slum dwellers. The reason for the initial movement into the slum area was related to satisfaction and dissatisfaction. The ability to meet initial expectations was usually mentioned as a reason for feeling satisfied, while failure to meet initial expectations (for example in terms of getting jobs, attending school, and acquiring property) usually led to disillusionment.

Both individual/household/economic factors and the location factors contribute differently to individuals’ satisfaction with their migration decision. Satisfaction is also multi-dimensional in that an individual may be satisfied by his or her economic condition but not by the location characteristics. How individuals perceived success was linked to satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Satisfaction is also mediated by gender and age as people of different ages and gender sometimes considered different aspects of slum life to denote whether they were satisfied or not. Whether this dissatisfaction results in a desire to move, actualization of movement depends on the relative value of these factors to migrants. It is also apparent that just as among international migrants, slum migrants also have to go through a social and cultural adaptation phase where they may end up accepting the slum condition as “normal,” with those who may fail to adapt to and cope with slum life expressing the desire to migrate away from slum locations. Although many migrants were not satisfied by conditions in the slum and the lives they were leading, many were hopeful that with perseverance their situation would improve for the better.

There are different determinants for economic satisfaction (employment) and social satisfaction (living environment and community facilities),2 although social/environmental dissatisfaction is more likely to be related with an expressed intention to move out of the slum area. Many people presented the poor environmental factors as potential push factors if they are to leave the slum settlements. However, people who are economically dissatisfied may decide to stay in the hope that their fortunes will change for the better. Some people may be satisfied by their jobs but not by the living environment and community amenities, and the reverse can also be true. Turning to Speare’s model, residential satisfaction in our study area was related to individual and location characteristics, mediated by perception of success and other considerations such as condition at area of origin. Our study found no direct effect on satisfaction between individual and location factors, but that individual definitions of success mediated this relationship, which in effect determined satisfaction levels for individuals.

Individual/household factors contribute to satisfaction in significant ways. For instance, as noted elsewhere, tenure status seemed to be a key measure of success and satisfaction, and an influential factor on how much longer the respondents intended to stay in the slum settlements.38 Those who were living in their own houses or were not paying rent were likely to indicate that they were satisfied, and were less likely to intend to move out of the slum. Since owning housing structures within the slum was seen as a measure of success, this suggests that success that is linked to purchase of fixed assets in the slums is discourage people from considering moving. In line with other studies on migration, the paper shows that house ownership seems to play a key role in satisfaction.38 This pattern should be interpreted with caution because it may be that those who are satisfied with slum life invest in fixed assets there because they are committed to staying. Likewise, those who are not satisfied may choose to invest elsewhere with the expectation of moving at a later date.

Before the age of 30, women are highly mobile and are least likely to own land or houses in the slum area, whereas after the age of 30 they are more likely than men to own houses and land in Nairobi and become more stable in the slums (NUHDSS data). Although women expressed dissatisfaction with slum conditions, they were less likely to report intentions to move out at older ages because they did not own land and houses outside of Nairobi, and many of them liked the independence that they had in the city. While, this paper does not focus on social bonds, older women may become more settled because they have more networks within the slum area compared to men. For example, a study in the same community noted that at older ages, women have better networks within the slum setting, leading to stronger social bonds for women than men.39 Research elsewhere has emphasized the importance of strong social bonds for satisfaction with residential location.18,40 There was also an intersection between individual factors and location factors in determining satisfaction. Social satisfaction was linked to issues such as autonomy for women owning a place of their own where they can make decisions. Elsewhere, Ying found that unmarried immigrants enjoy greater satisfaction than married immigrants.41 This may be related to the greater freedom unmarried migrants enjoy in making decisions. Economic satisfaction was usually related to ability to get a job, to get a better paying job, to improve status relative to the area of origin, and the ability to pay rent, pay school fees, and buy land/build houses in the ares of both origin and destination areas. Thus, to a large extent, satisfaction with migration and residential location may not only be related to the destination, but may also be related to events in the area of origin.

Perception of satisfaction vary with age, thus the “age cohort effect” may be at play.16,27,28 For instance, different age groups focus on different issues to explain satisfaction. This may be related to the stage of their life cycle. Younger age groups focused more on education, middle age groups on the job market, and older age groups on other social indicators such as not being harassed. Location factors, including lack of amenities like toilets, good housing, clean water, and good schools, were often related to dissatisfaction across age groups.

The high mobility experienced by the slum areas as evidenced by work elsewhere may be an indicator of the high levels of dissatisfaction migrants have with slum life.42 Nilsson regarded cities as “escalator regions” because of the opportunities they provide to enable individuals to move up the social ladder.43 He also noted, however, that in some cases, people who move to the cities may actually move into an urban underclass and may “not step onto an escalator.” It may be that migrants are returning to rural areas or moving to other locations after failing to cope or that they are unable to climb the “escalator” out of slum life. However, in situations of extreme deprivation, both social and economic satisfaction cannot be directly linked to emigration as some people may not have an option except to stay and “persevere.” This is mainly because, as noted by Speare, if the benefits of moving do not outweigh the costs, then individuals may decide to stay.32 Thus, the use of a word like “perseverance” may have reflected migrants’ cost-benefit analyses. Those who are dissatisfied may not plan to move out of the slum because of anticipation of future benefits. At the same time, challenges associated with living in slum areas do not automatically signify dissatisfaction, as people may perceive their life as better off than it was before moving into the slum area. Almost everyone living in the slums is concerned about the environment and lack of amenities. However, even if there are economic constraints, many migrants still think they stand a better chance of making some money in the city compared to rural areas. As a result, they continue to reside in cheaper, informal settlements because for them, the economic benefits of living in the city outweigh the location challenges they face in the informal settlements.

Just like migrants elsewhere, those who migrate to slum settlements do so to improve their situation in life. In spite of high levels of dissatisfaction with slum life, many migrants continue to reside in slum areas if they perceive no viable alternatives or if they think that some fundamental aspects of their lives will continue to improve, even if other aspects will continue to deteriorate. Understanding issues that migrants consider critical in determining their satisfaction with living in slum areas and the city of Nairobi in general, and what determines whether they stay or move out of the slums would be vital in determining how to intervene and who to target in order to improve their lives. Clearly, while lack of livelihood opportunities is a major issue of concern among slum dwellers, it is evident that many people consider the prospects of generating some income to be much higher in the city than in rural areas. While they recognize that the poor environmental conditions in the slums are a major health hazard and source of indignity in their lives, many people will continue living in slum settlements since this is the only place that they can afford in the city. Efforts to improve the lives of slum dwellers should, therefore, focus on providing the social and environmental amenities to enable the millions of low-income people staying in these locations live healthier and dignified lives.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the following organizations for their support which made field work and data analysis possible. The Wellcome Trust grant number GR 07830M, The Rockefeller Foundation Grant number 200 3 AR021, Hewlett Foundation Grant number 2006-8376 and The National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant number 3 P30 AG017248-03S1. We would also like to thank our colleagues at APHRC for their invaluable comments. APHRC is a member of the INDEPTH network.

References

- 1.Safi M. Immigrants’ life satisfaction in Europe: between assimilation and discrimination: observatoire Sociologique du Changement (OSC); 2008. http://www.stanford.edu/group/scspi/pdfs/rc28/conference_2008/p9183.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2009.

- 2.Jong GF, Chamratrithirong A, Quynh-Giang T. For better, for worse: life satisfaction consequences of migration. Int Migr Rev. 2002;36(3):838–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2002.tb00106.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oucho JO. Recent internal migration processes in Sub-Saharan Africa: determinants, consequences, and data adequacy issues. In: Bilsborrow RE, ed. Migration, Urbanization, and development: new directions and issues. UNFPA and Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998: 89-120.

- 4.Davin D. Gender and rural-urban migration in China gender and development. Gend Dev. 1996;4(1):24–30. doi: 10.1080/741921947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agwanda AO, Bocquier P, Khasakhala A, Owuor SO. The effect of economic crisis on youth precariousness in Nairobi: an analysis of itinerary to adulthood of three generations of men and women; 2004. http://www.dial.prd.fr/dial_publications/PDF/Doc_travail/2004-04.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2009.

- 6.Linares OF. Going to the city and coming back? Turnaround migration among the Jola of Senegal, Africa. Africa. 2003;73(1):113–32. doi: 10.3366/afr.2003.73.1.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gmelch G. Return migration. Annu Rev Anthropol. 1980;9:135–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.09.100180.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Todaro MP. A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries. Am Econ Rev. 1969;59:138–48. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newbold KB. Migrants and migrations: comparing lifetime and fixed-interval return and onward migration. Econ Geogr. 2001;77(1):23–40. doi: 10.2307/3594085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caldwell JC. Determinants of rural-urban migration in Ghana. Popul Stud. 1969;22(3):361–77. doi: 10.2307/2173001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilborrow RE, McDevitt TM, Kiossoudji S, Fuller R. The impact of origin community characteristics on rural-urban out-migration in a developing country. Demography. 1987;24:191–210. doi: 10.2307/2061629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berhanu B, White M. War, famine, and female migration in Ethiopia, 1960-1989. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2000;49(1):91–113. doi: 10.1086/452492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown LA, Goetz AR. Development-related contextual effects and individual attributes in third world migration processes: a Venezuelan example. Demography. 1987;24(4):497–516. doi: 10.2307/2061388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berry JW. Lead article: immigration, acculturation, adaptation. Appl Psychol. 1997;46(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuller TD. Migrant evaluations of the quality of urban life in Northeast Thailand. J Dev Areas. 1981;16:87–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran TV, Nguyen TD. Gender and satisfaction with the host society among Indochinese refugees. Int Migr Rev. 1994;28(2):323–37. doi: 10.2307/2546735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogt RJ, Allen JC, Cordes S (2003) Relationship between community satisfaction and migration intentions of rural Nebraskans. Great Plains Res. 2003; 13(1).

- 18.Fokkema T, Gierveld J, Nijkamp P. Big cities, big problems: reason for the elderly to move? Urban Stud. 1996;33:353–77. doi: 10.1080/00420989650012059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee BA, Oropesa RS, Kanan JW. Neighborhood context and residential mobility. Demography. 1994;31:249–70. doi: 10.2307/2061885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.South SJ, Deane GD. Race and residential mobility: individual determinants and structural constraints. Soc Forces. 1993;72:147–67. doi: 10.2307/2580163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruback BR, Pandey J, Begum HA, Tariq N, Kamal A. Motivations for and satisfaction with migration: an analysis of migrants to New Delhi, Dhaka, and Islamabad. Environ Behav. 2004;36:814–38. doi: 10.1177/0013916504264948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.APHRC. Health and livelihood needs of poor of residents of informal settlements of Nairobi city. Occasional Study Report 2002. http://www.chs.ubc.ca/archives/files/Health%20and%20Livelihood%20Needs%20of%20Residents%20of%20Informal%20Settlements%20in%20Nairobi%20City.pdf Accessed on April 14, 2009.

- 23.UN HABITAT. The challenges of slums: global report on human settlements; 2003.

- 24.Chepngeno G, Ezeh AC. 'Between a rock and a hard place': perception of older people living in Nairobi City on return migration to rural areas. Global Ageing: Issues and Action. 2007;4(3):67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goyder J. Migration and regional differences in life satisfaction in the anglophone provinces. Can J Sociol. 1995;20(3):287–307. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marsden LR, Tepperman LJ. The migrant wife: the worst of all worlds. J Bus Ethics. 1985;4:205–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00705621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gory M, Ward R, Sherman S. The ecology of aging: neighborhood satisfaction in an older populations. Socio Q. 1985;26(3 Special Feature: the Sociology of Nuclear Threat):405–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.1985.tb00235.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuba L, Hummon DM. Constructing a sense of home: place affiliation and migration across the life cycle. Socio Forum. 1993;8(4):547–72. doi: 10.1007/BF01115211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawton P. Environment and aging. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marans RW, Rodgers W. Toward and understanding of community satisfaction. Metropolitan America in contemporary perspective. New York: Halstead Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu M. Analyzing migration decision making: relationships between residential satisfaction, mobility intentions, and moving behavior. Demography. 1977;14(2):147–67. doi: 10.2307/2060573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Speare A. Residential satisfaction as an intervening variable in residential mobility. Demography. 1974;11(2):173–88. doi: 10.2307/2060556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landale NS, Guest AM. Constraints, satisfaction and residential mobility: Speare’s model reconsidered. Demography. 1985;22(2):199–222. doi: 10.2307/2061178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fabrizio SM, Neill JT. Cultural adaptation in outdoor programming. Aust J Outdoor Educ. 2005;9(2):44–56. [Google Scholar]

- 35.APHRC. Population and health dynamics in Nairobi informal settlements: report of the Nairobi Cross-sectional Slums Survey (NCSS) 2000. APHRC; 2002

- 36.Muindi K, Zulu E, Beguy D, Mudege NN, Batten L. Characteristics of migrants in Nairobi’s informal settlements. XXVI IUSSP International Population Conference. Marrakech; 2009.

- 37.World Bank. Kenya poverty and inequality assessment: World Bank; 2008

- 38.Ahlbrandt RS. Neighborhoods, people and community. New York: Plenum Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mudege NN, Ezeh AC. Gender, aging, poverty and health: survival strategies of older men and women in Nairobi slums. J Aging Stud. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Oh JH. Social bonds and the migration intentions of elderly urban residents: the mediating effect of residential satisfaction. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2003;22:127–46. doi: 10.1023/A:1025067623305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ying Y. Immigration satisfaction of Chinese Americans: an empirical examination. J Community Psychol. 1996;24:3–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199601)24:1<3::AID-JCOP1>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beguy D, Zulu EM, Bocquire F. Migration patterns in slum settlements: evidence from the NUHDSS. Nairobi: APHRC; unpublished.

- 43.Nilsson K. Moving into the city and moving out again: Swedish evidence from the cohort born in 1968. Urban Stud. 2003;40(7):1243–58. doi: 10.1080/0042098032000084587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]