Abstract

Heme oxygenase (HO)-1 is a cytoprotective molecule that is induced during the response to injury. An increase in HO-1 is an acute indicator of inflammation, and early induction of HO-1 has been suggested to correlate with severity of injury. While a great deal is known about the induction of HO-1 by inflammatory mediators and bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), much less is known about the effects of anti-inflammatory mediators on HO-1 expression. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is known to play a critical role in suppressing the immune response, and the TGF-β1 isoform is expressed in inflammatory cells. Thus, we wanted to investigate whether TGF-β1 could inhibit the expression of HO-1 during exposure to an inflammatory stimulus in macrophages. Here we demonstrate that TGF-β1 is able to downregulate LPS-induced HO-1 in mouse macrophages, and this reduction in HO-1 occurred through signaling of TGF-β1 via its type I receptor, and activation of Smad2. This TGF-β1 response is dependent on an intact Ets-binding site (EBS) located 93 base pairs upstream from the mouse HO-1 transcription start site. This EBS is known to be important for Ets-2 transactivation of HO-1 by LPS stimulation, and we show that TGF-β1 is able to suppress LPS-induced Ets-2 mRNA and protein levels in macrophages. Moreover, silencing of Smad2 is able to prevent the suppression of both HO-1 and Ets-2 by TGF-β1 during exposure to LPS. These data suggest that the return of HO-1 to basal levels during the resolution of an inflammatory response may involve its downregulation by anti-inflammatory mediators.

Keywords: gene regulation, inflammatory response, cytoprotective molecule

INTRODUCTION

The heme oxygenase (HO) enzyme system catalyzes the initial and rate-limiting step in heme degradation (Tenhunen, et al., 1969; Tenhunen, et al., 1968). HO-1 is the inducible isoform that is upregulated in response to pathophysiologic stimuli including inflammation and endotoxin exposure (Abraham, et al., 2005; Alam, et al., 2007; Maines, et al., 2005; Ryter, et al., 2006). Downstream products of heme degradation by HO-1, carbon monoxide and biliverdin (which is subsequently reduced to bilirubin), have anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties respectively (Otterbein, et al., 2000; Stocker, et al., 1987; Vile, et al., 1993). Induction of HO-1 is an acute indicator of inflammation, and early induction of HO-1 in sepsis has been suggested to correlate with severity of disease (Jao, et al., 2005). The products of HO-1–mediated heme degradation act in a compensatory means to inhibit the inflammatory response (Otterbein, et al., 2000; Overhaus, et al., 2006), however this induction of endogenous HO-1 may not be sufficient or adequately prolonged to alleviate the detrimental outcome in sepsis. To highlight this concept, we showed previously that overexpression of HO-1 in transgenic mice, allowing sustained expression of HO-1, led to improved outcome in polymicrobial sepsis compared with wild-type mice (Chung, et al., 2008).

As inflammation resolves, the upregulation of endogenous HO-1 is not sustained, and expression of HO-1 returns to baseline. This raises the question of whether the reduction in HO-1 levels occurs passively, related to a decrease in pro-inflammatory mediators, or whether the expression of counterregulatory anti-inflammatory mediators during the resolution phase of an inflammatory process (Fujiwara, et al., 2005) can lead to downregulation of HO-1. While a great deal is known about the induction of HO-1 by inflammatory mediators and endotoxin (Alam, et al., 2003; Alam, et al., 2007; Choi, et al., 1996; Otterbein, et al., 1995; Pellacani, et al., 1998; Wiesel, et al., 2000a; Yet, et al., 1997), much less is known about the effects of anti-inflammatory mediators on HO-1 expression.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is known to play a critical role in suppressing the immune response (Li, et al., 2006; Yoshimura, et al., 2010), and the TGF-β1 isoform is predominantly expressed in the immune system. TGF-β1 is a pleiotrophic molecule with immunoregulatory properties (Feng, et al., 2005; Yoshimura, et al., 2010), as shown by mice deficient in TGF-β1 developing an excessive inflammatory response and early death (Kulkarni, et al., 1993; Shull, et al., 1992). TGF-β1 has the ability to deactivate macrophages (Fujiwara, et al., 2005; Tsunawaki, et al., 1988), even during endotoxin exposure (Werner, et al., 2000), and ingestion of apoptotic cells by macrophages induce TGF-β1 secretion resulting in accelerated resolution of inflammation (Huynh, et al., 2002). Thus, we wanted to investigate whether TGF-β1 could inhibit the expression of HO-1 during exposure to an inflammatory stimulus in macrophages.

TGF-β1 produces its biologic response by signaling through heterodimeric type I and type II receptors, termed TGF-βRI and TGF-βRII (Feng, et al., 2005). Ligand binding leads to activation of the receptors, and TGF-βRI subsequently phosphorylates two receptor-associated Smad proteins, Smad2 and Smad3. Smad2 and Smad3 then interact with Smad4, and these complexes translocate to the nucleus to regulate the transcription of target genes, in conjunction with other nuclear proteins (Feng, et al., 2005; Yoshimura, et al., 2010). Initial studies suggested that the Smad responsible for immune regulation was Smad3, as knockout mice developed inflammatory diseases (Yang, et al., 1999). However, more recent data from studies using conditional knockout mice have shown that Smad2 and Smad3 may be redundantly essential (Takimoto, et al., 2010). Interestingly, Smad-mediated transcriptional events can lead to either activation or suppression of target genes by TGF-β1, and these events are determined by cell type, cell environment, and DNA sequence–dependent factors (Feng, et al., 2005). For example, TGF-β1 can lead to induction of HO-1 in renal epithelial cells (Traylor, et al., 2007), yet suppression of HO-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells exposed to interleukin-1β (Pellacani, et al., 1998). Similar to HO-1 gene regulation, much more is known about Smad-mediate transcriptional activation than is known about transcriptional repression by TGF-β family members. Thus, our present goal is to elucidate the regulation of HO-1 by the anti-inflammatory mediator TGF-β1 in macrophages, and to understand the mediators downstream of TGF-β1 responsible for HO-1 suppression during an inflammatory stimulus.

Material and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

Murine macrophages (RAW 264.7) were cultured as described previously (Ejima, et al., 2002). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli and SB431542, a small molecule inhibitor of activin receptor-like kinase 5 (TGF-βRI), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Recombinant human TGF-β1 was purchased from PeproTech Inc.

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis

RNeasy mini RNA isolation kit (Qiagen) was used to extract total RNA from cultured cells. Northern blot analysis was performed as described previously (Chen, et al., 2001; Wiesel, et al., 2000b). In brief, RNA samples (10 μg) were electrophoresed in a 1.3% agarose gel containing 3.7% formaldehyde and then transferred to NitroPure filters (GE Osmonics Inc.). The filters were then hybridized with random primed, [α-32P]dCTP-labeled HO-1 or Ets-2 probes. To correct for the differences in RNA loading, blots were subsequently hybridized with a γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe complementary to 18S rRNA.

Total protein isolation and Western blot analysis

Whole cell lysates (10 μg) of RAW 264.7 cells were boiled and resolved on 4–12% SDS-PAGE gel (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred on Pure nitrocellulose membranes and immunoblotted using SuperSignal® West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology). Antibodies targeting HO-1 (Stressgen Biotechnology), Ets-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phosphor-Smad2 (serines 465 and 467, Millipore), phosphor-Smad3 (serines 423 and 425, Millipore), and signaling proteins p38, ERK, SAPK/JNK, Smad2, Smad3, Smad4, and Smad7 (Cell Signaling Technology) were diluted to 1:1000 before use.

Luciferase reporter constructs and expression plasmids

HO-1 luciferase reporter plasmid HO-1-(−4045/+74), deletion mutants, and mutants of Ets binding sites (EBSs) at bp −125 (mEBS1) and −93 (mEBS2) were described previously (Chung, et al., 2005; Chung, et al., 2006). Expression plasmid pcDNA3-hSmad2 (Hayashi, et al., 1997) was a gift from Dr. James N. Topper. A mutant construct of hSmad2 phosphorylation with a substitution of alanine for the wild-type serines at position 464, 465, and 467 (Smad2m), was generated as described (Fowles, et al., 1998).

Transient transfections and reporter assays

HO-1 reporter constructs were used for transient transfection assays of RAW 264.7 cells as described previously (Wiesel, et al., 2000a), and 3 × 105 cells/well were plated in triplicate on 6-well plates and incubated overnight. Using the FuGENE 6 reagent (Roche Applied Science), cells were transfected with 250 ng of HO-1 reporter plasmids, and in designated experiments co-transfected with 200 ng/well of expression constructs pcDNA3-hSmad2 (Smad2) and pcDNA3-hSmad2m (Smad2m).

Silencing of Smad2 and Smad3 in mouse macrophages

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) plasmids for Smad2 and Smad3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Clone ID #s; NM_010754.2-928s1c1, NM_016769.2-2793s1c1, NM_016769.2-1137s1c1, NM_016769.2-1430s1c1), and silenced clones were generated as described (Hung, et al., 2010). Briefly, after transfection of RAW 264.7 cells with the Smad2 or Smad3 shRNA plasmids, stably transfected cells were selected by resistance to puromycin (5 μg/ml) after two weeks of exposure. Puromycin resistant cells containing the Smad2 and Smad3 shRNA plasmids, compared with cells containing the control vector pLKO.1-puro with a non-related sequence, were used for Western blot analyses.

Analysis of data

Comparisons between groups, where indicated, were made by factorial ANOVA, followed by Fisher’s least significant difference test. Statistical significance is accepted at P<0.05.

Results

TGF-β1 suppresses HO-1 expression (mRNA and protein) in macrophages activated by LPS

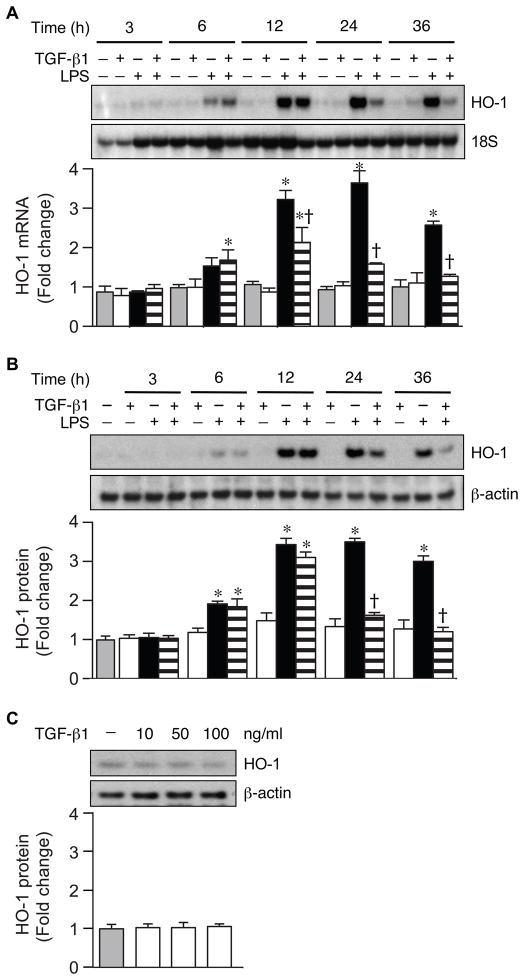

To determine the effects of TGF-β1 on HO-1 expression in mouse macrophages, we treated RAW 264.7 cells with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), LPS (10 ng/ml), or TGF-β1 plus LPS, and harvested RNA and protein at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 hours after cell treatment. HO-1 mRNA and protein levels began to increase by 6 hours, and a more striking increase in HO-1 was evident after 12 hours of LPS treatment (Fig. 1A and 1B respectively). The administration of TGF-β1 decreased LPS-induced HO-1 mRNA starting at 12 hours, although HO-1 mRNA and protein levels were markedly decreased by 24 hours. We found that administering TGF-β1 prior to LPS, simultaneous with LPS, or up to 2 hours after LPS led to a similar suppression of HO-1 (data not shown). Thus, in Figure 1 and the remainder of experiments using combined treatments, LPS was administered immediately followed by TGF-β1. Prior publications have described an increase in HO-1 expression by TGF-β1 in epithelial cells (Hill-Kapturczak, et al., 2000; Lin, et al., 2007; Ning, et al., 2002). Thus, we administered increasing doses of TGF-β1 to RAW 264.7 cells (10, 50, and 100 ng/ml), but we did not find any evidence of HO-1 induction after 24 hours in these mouse macrophages (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

TGF-β1 suppresses LPS-induced HO-1 expression. Total RNA and protein were extracted from RAW 264.7 cells after TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), LPS (10 ng/ml), or LPS+TGF-β1 administration at various time points. The expression of HO-1 mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels were assessed by Northern blot and Western blot analyses. HO-1 protein levels were also assessed during exposure to different doses of TGF-β1 (10, 50, and 100 ng/ml) for 24 hours (C). 18S (mRNA) and β-actin (protein) were used as loading controls. These experiments were performed at least three independent times, and the fold change in mRNA (A) or protein (B and C) levels were quantitated as signal intensity corrected for loading in control cells (gray bars) or cells exposed to TGF-β1 (white bars), LPS (black bars), or LPS+TGF-β1 (horizontal striped bars). The values represent mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 versus control and TGF-β1, and † P<0.05 versus LPS.

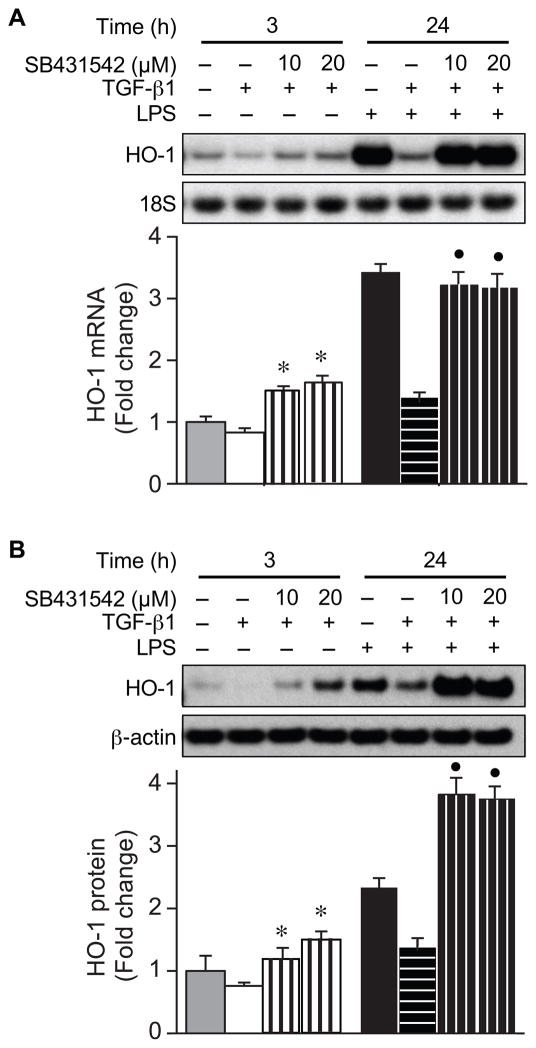

To ascertain the signaling pathway(s) responsible for downregulation of HO-1 by TGF-β1, we used a specific inhibitor of activin receptor-like kinase 5 (TGF-βR1), SB431542. Macrophages were treated with SB431542 (10 and 20 μM), in the presence of TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) or LPS (10 ng/ml) plus TGF-β1, and RNA and protein were harvested 24 h after administration. SB431542 blocked the downregulation of HO-1 mRNA and protein by TGF-β1 in the presence or absence of LPS (Fig. 2). These data suggest that TGF-β1 is able to inhibit the expression of HO-1 even in the presence of an inflammatory stimulus in macrophages, and this process is going through the TGF-βRI signaling pathway.

Fig. 2.

TGF-βRI inhibitor, SB431542, blocks the downregulation of HO-1 by TGF-β1. Total RNA and protein were extracted from RAW 264.7 cells 3 hours and 24 hours after administration of TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), LPS (10 ng/ml), or LPS+TGF-β1, in the presence or absence of the TGF-βRI inhibitor, SB431542 (10 and 20 μM). The expression of HO-1 mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels were assessed by Northern blot and Western blot analyses. 18S (mRNA) and β-actin (protein) were used as loading controls. These experiments were performed at least three independent times, and the fold change in mRNA (A) or protein (B) levels were quantitated as signal intensity corrected for loading in control cells (gray bars) or cells exposed to TGF-β1 (white bars), LPS (black bars), or LPS+TGF-β1 (horizontal striped bar). Samples were also exposed to SB431542, in the absence or presence of LPS (vertical striped bars). The values represent mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 versus TGF-β1, and ● P<0.05 versus LPS+TGF-β1.

TGF-β1 increases p-Smad2 in the presence of LPS

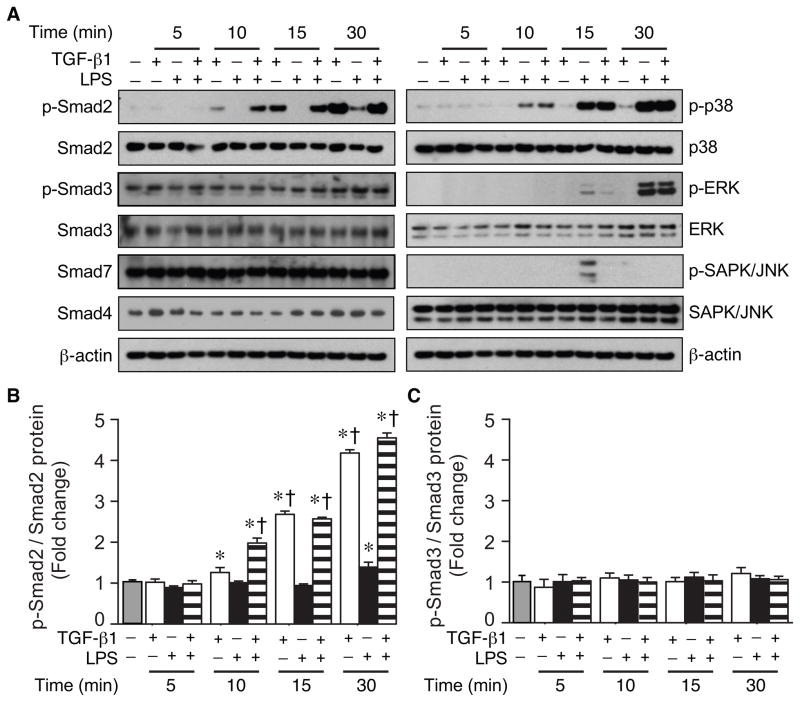

To identify the signaling molecules that are involved in the regulation of HO-1 by TGF-β1, we harvested protein from macrophages after TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), LPS (10 ng/ml), or LPS plus TGF-β1 administration. LPS alone did not have a significant effect on overall Smad2 or Smad3 expression (Fig. 3A), and after 30 minutes of LPS exposure, phosphorylated (p)-Smad2 was slightly increased. However, TGF-β1 markedly increased p-Smad2, in the presence or absence of LPS (Fig. 3A), with a > 4 fold increase of p-Smad2/total Smad2 by 30 minutes (Fig. 3B). In contrast, TGF-β1 did not significantly alter phosphorylation of Smad3 (Fig. 3C). TGF-β1 also did not change the overall expression of Smad4 or Smad7 (Fig. 3A). Assessment of the MAP kinase signaling pathways showed no alteration in p38, p-p38, ERK, p-ERK, or SAPK/JNK by TGF-β1 in the presence of endotoxin (Fig. 3A). Although, the level of p-SAPK/JNK was transiently increased after 15 minutes of LPS exposure, and this induction was prevented by TGF-β1.

Fig. 3.

Effect of TGF-β1 on expression of signaling molecules during LPS exposure. RAW 264.7 cells were stimulated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), LPS (10 ng/ml), or a combination of LPS+TGF-β1. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot for phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3, and total Smad2, 3, 4, and 7 (A). MAPK signaling proteins (p38, ERK, SAPK/JNK, and their phosphorylated proteins) were also analyzed by Western blot (A). β-actin was used as a loading control. The fold change in protein levels of p-Smad2 corrected for total Smad2 (B) and p-Smad3 corrected for total Smad3 (C) was assessed in control cells (gray bar) or cells exposed to TGF-β1 (white bars), LPS (black bars), or LPS+TGF-β1 (horizontal striped bars). The values represent mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 versus control, and † P<0.05 versus LPS. The experiments in all panels were performed three independent times.

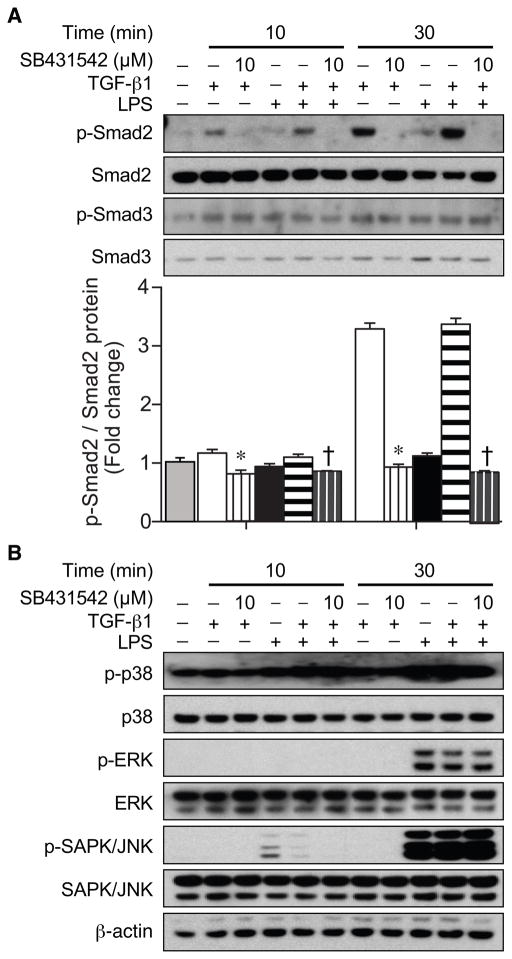

We next assessed the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 in macrophages after treatment with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) or LPS (10 ng/ml) plus TGF-β1 in the presence or absence of the TGF-βRI inhibitor SB431542 (10 μM, Fig. 4). Smad2 phosphorylation by TGF-β1 was completely prevented by SB431542 administration (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the phosphorylation status of Smad3 (Fig. 4A) and other signaling molecules (p38, ERK, SAPK/JNK) was not increased by TGF-β1, nor altered by the TGF-βRI inhibitor (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that phosphorylation of Smad2 may be an important mediator in the regulation of HO-1 by TGF-β1.

Fig. 4.

Effect of TGF-βRI inhibitor on TGF-β1 signaling during LPS exposure. Cells were treated with the TGF-βRI inhibitor (SB431542, 10 μM) for 30 minutes before TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), LPS (10 ng/ml), or LPS+TGF-β1 treatment. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blots for total and phosphorylated forms of Smad2 and Smad3 (A), and MAPK signaling proteins (p38, ERK, SAPK/JNK, and their phosphorylated proteins) (B).β-actin was used as a loading control. The fold change in protein levels of p-Smad2 corrected for total Smad2 (A) was assessed in control cells (gray bar) or cells exposed to TGF-β1 (white bars), LPS (black bars), or LPS+TGF-β1 (horizontal striped bars). Cells also exposed to SB431542 have a vertical stripe. The values represent mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 versus TGF-β1, and † P<0.05 versus LPS+TGF-β1. These experiments were performed three independent times.

TGF-β1 suppresses LPS-induced HO-1 promoter activity

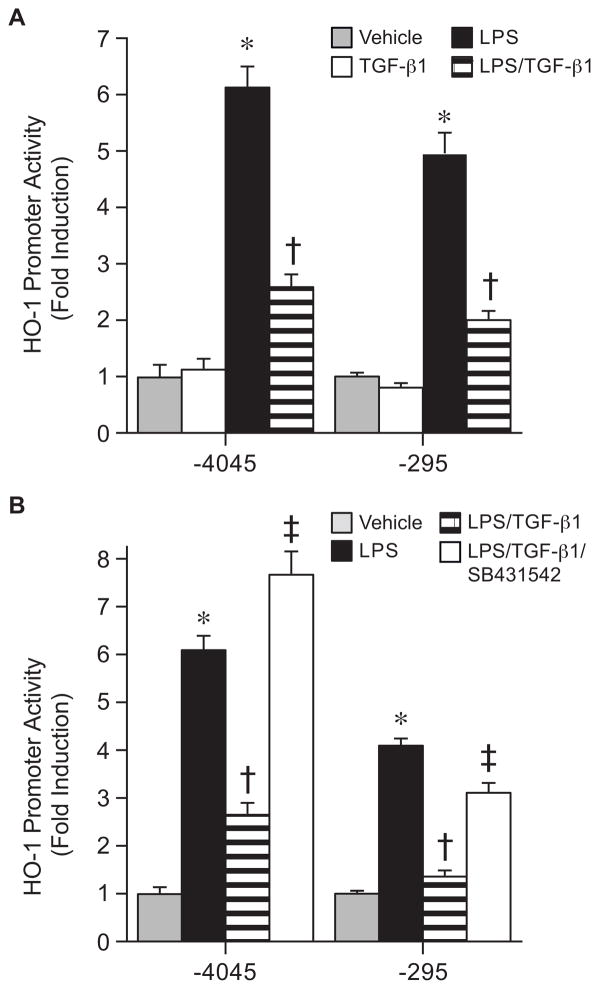

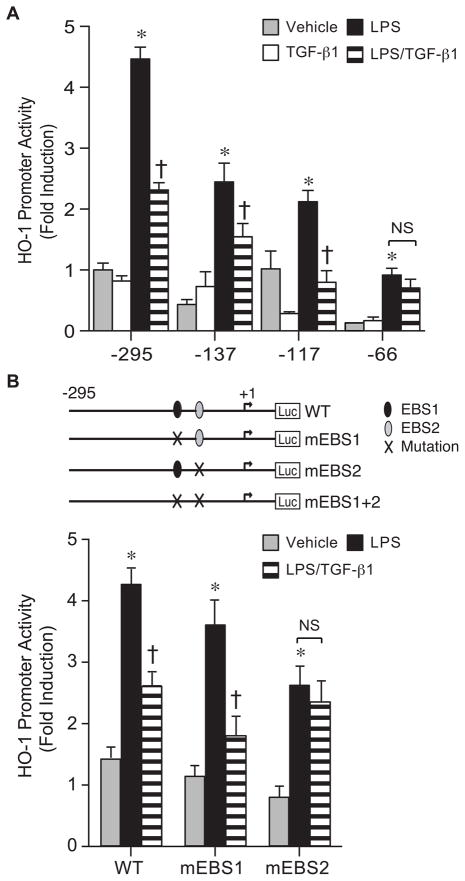

To understand whether specific cis-acting binding sites are responsible for the TGF-β1 effects, we initially assessed HO-1 promoter constructs −4045/+74 and −295/+74. In both constructs, TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) suppressed HO-1 transactivation by LPS (10 ng/ml), suggesting that critical cis-acting element(s) are downstream of bp −295 (Fig. 5A). In addition, downregulation of the HO-1 promoter constructs by TGF-β1 was prevented by the TGF-βR1 inhibitor, SB-421542 (10 μM, Fig. 5B). Further deletion of the HO-1 promoter demonstrated that the suppression of LPS-induced HO-1 promoter activity was maintained in construct −117/+74, but lost in construct −66/+74 (Fig. 6A). These data suggest the importance of cis-acting element(s) located between bp −117 and −66 of the downstream HO-1 promoter. Mutation of individual EBS sites showed that only disruption of EBS2 (−93), but not EBS1 (−125), abrogated downregulation of the HO-1 promoter by TGF-β1 (Fig. 6B). The EBS2 site is known to bind the HO-1 activator Ets-2 (Chung, et al., 2005), with the HO-1 suppressor Elk-3 binding more efficiently at the EBS1 site (Chung, et al., 2006). These data suggest that the effect of TGF-β1 occurs by altering Ets family members that are activators, not repressors, of the HO-1 promoter.

Fig. 5.

TGF-β1 suppresses HO-1 promoter activity during LPS exposure. (A) HO-1 promoter constructs, HO-1(−4045/+74) and HO-1(−295/+74), were transfected (250 ng/well) in RAW 264.7 cells and promoter activity was analyzed after exposure to vehicle (gray bars), TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml, white bars), LPS (10 ng/ml, black bars) or LPS+TGF-β1 (horizontal striped bars). * P<0.05 versus Vehicle and TGF-β1, † P<0.05 versus LPS. (B) HO-1 promoter constructs, HO-1(−4045/+74) and HO-1(−295/+74), were transfected (250 ng/well) in RAW 264.7 cells and promoter activity was analyzed after exposure to vehicle (gray bars), LPS (10 ng/ml, black bars), LPS+TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml, horizontal striped bars), or LPS+TGF-β1 and the TGF-β1R inhibitor SB431542 (10 μM, white bars). The values represent mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 versus vehicle, † P<0.05 versus LPS, and ‡ P<0.05 versus LPS+TGF-β1. In both (A) and (B), three independent experiments were performed, and n=12.

Fig. 6.

EBS2 site is critical for the suppression of HO-1 promoter activity by TGF-β1. (A) Deletion constructs of the HO-1 promoter (−295/+74, −137/+74, −117/+74, and −66/+74) were transfected (250 ng/well) in RAW 264.7 cells, and promoter activity was analyzed after exposure to vehicle (gray bars), TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml, white bars), LPS (10 ng/ml, black bars), or LPS+TGF-β1 (horizontal striped bars). The values represent mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 versus vehicle and TGF-β1, and † P<0.05 versus LPS. NS, not significant. (B) WT HO-1 (−295/+74) promoter construct compared with mutated constructs (m) of EBS sites were transfected (250 ng/well) in RAW 264.7 cells and promoter activity was analyzed after exposure to vehicle (gray bars), LPS (10 ng/ml, black bars), or LPS+TGF-β1 (horizontal striped bars). * P<0.05 versus vehicle, and † P<0.05 versus LPS. NS, not significant. Three independent experiments were performed, and n=6.

Mutation of the EBS1 site did not result in enhanced induction of HO-1 promoter activity, as previously shown (Chung, et al., 2006). However, the present experiments were performed with a much lower dose of LPS (10 ng/ml) compared with previous studies (LPS, 500 ng/ml) (Chung, et al., 2006). These data lead us to hypothesize that the suppressive effects of LPS on Elk-3 expression may be less complete with a lower dose of LPS (10 ng/ml).

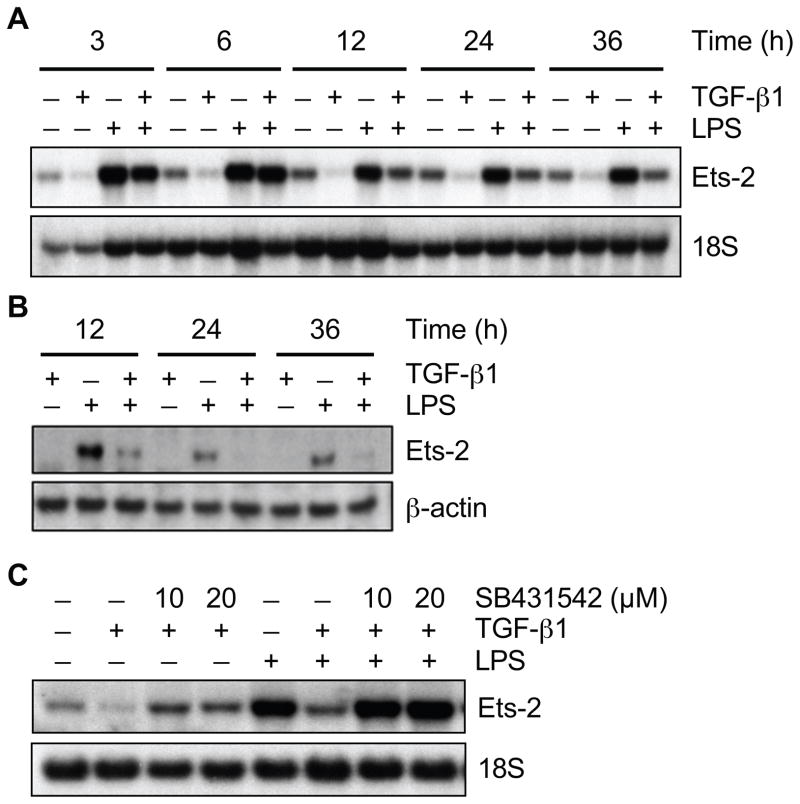

TGF-β1 downregulates the expression of Ets-2 during LPS exposure

We have shown previously that Ets-2 binding at the EBS2 site is critical for the acute (6 hours) induction of HO-1 by LPS (Chung, et al., 2005). However, with the late suppression of HO-1 by TGF-β1 (24 hours, Fig. 1), we wanted to determine whether the effect of TGF-β1 could indirectly occur via suppression of Ets-2 mRNA and protein. This was supported by experiments using cycloheximide, which showed a blunted suppression of LPS-induced HO-1 by TGF-β1 (Suppl. Fig. 1), suggesting this response depended in part on an alteration in protein synthesis. We harvested RNA and protein from mouse macrophages after treatment with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) or LPS (10 ng/ml) plus TGF-β1 at different time points. The Northern blot for HO-1 expression in Fig. 1A was also assessed for Ets-2. TGF-β1 inhibited LPS-induced expression of Ets-2 mRNA starting at 12 hours, and continued through 36 hours (Fig. 7A). Ets-2 protein expression was also downregulated by TGF-β1 at 12, 24, and 36 hours after LPS stimulation (Fig. 7B), and this inhibition preceded the suppression of HO-1 protein by TGF-β1 (Fig. 1A). Treatment with the inhibitor of TGF-βRI (SB431542, 10 and 20 μM) blocked the downregulation of Ets-2 message by TGF-β1, both in the presence of LPS and at baseline (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

TGF-β1 downregulates the HO-1 transactivator, Ets-2, during LPS exposure. Total RNA and protein were extracted from RAW 264.7 cells after TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), LPS (10 ng/ml), or LPS+TGF-β1 exposure at various time points (as depicted). The expression of Ets-2 mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels were assessed by Northern blot and Western blot analyses respectively. (C) Ets-2 protein levels were also analyzed 36 hours after exposure to TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), LPS (10 ng/ml), or LPS+TGF-β1, in the presence or absence of TGF-βRI inhibitor, SB431542 (10 and 20 μM). Three independent experiments were performed.

Smad2 is an important mediator of TGF-β1 downregulation of both HO-1 and Ets-2 during an inflammatory stimulus

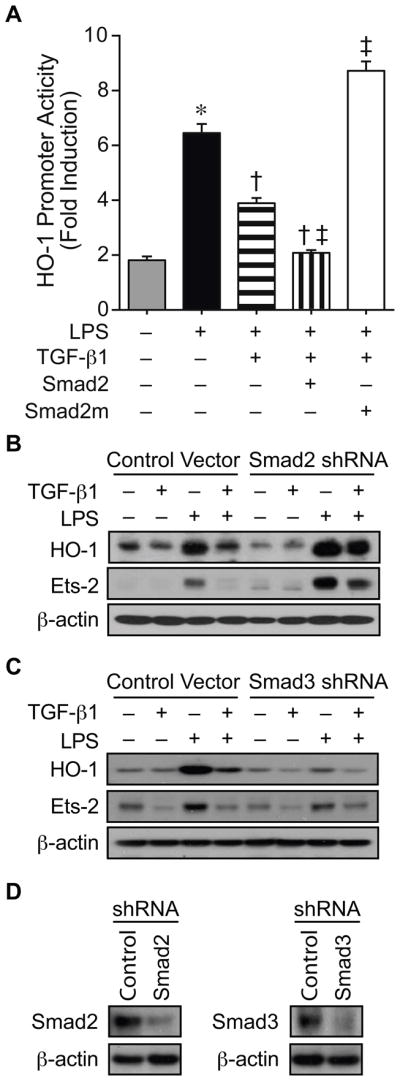

To determine whether the effects of Smad2 phosphorylation altered HO-1 promoter activity, we either overexpressed wild-type (WT) Smad2 (200 ng/well) or a non-phosphorylated mutant of Smad2 at position 464, 465, and 467 (Smad2m, 200 ng/well) with HO-1 promoter construct −295/+74. Overexpression of WT Smad2 plus TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) led to a further decrease in HO-1 promoter activity in the presence of LPS (10 ng/ml), and overexpression of Smad2m prevented this suppression of HO-1 promoter by TGF-β1 (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, shRNA of Smad2 in macrophages abrogated not only the suppression of LPS-induced HO-1, but also Ets-2, by TGF-β1 (Fig. 8B). In contrast, the suppression of LPS-induced HO-1 and Ets-2 by TGF-β1 was maintained in macrophages silenced for Smad3 (Fig. 8C). These data suggest that Smad2, more than Smad3, is important for the suppression of LPS-induced HO-1 and Ets-2 by TGF-β1. Interestingly, HO-1 induction by LPS appears to be less in the Smad3 silenced cells compared with control shRNA cells. These data imply that Smad3, different from Smad2, may be involved in the induction of HO-1 by LPS.

Fig. 8.

Smad2 is critical for TGF-β1 suppression of HO-1 during LPS exposure. (A) HO-1 promoter construct (−295/+74, 250 ng/well) was co-transfected into RAW 264.7 cells with a control plasmid, or with an expression plasmid for WT Smad2 (200 ng/well, vertical striped bar) or a Smad2 mutant not allowing phosphorylation at positions 464, 465, and 467 (Smad2m, 200 ng/well, white bar). The cells were exposed to vehicle (gray bar), LPS (10 ng/ml, black bar) or LPS+TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml, horizontal striped bar) in combination with the expression plasmids as depicted, and then analyzed for luciferase activity. * P<0.05 versus vehicle, † P<0.05 versus LPS, and ‡ P<0.05 versus LPS+TGF-β1. Two independent experiments were performed, and n=6. RAW 264.7 cells were stably transfected with a control vector, or with shRNA for Smad2 (B) or Smad3 (C). These groups of cells were then exposed to vehicle, TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), LPS (10 ng/ml), or LPS+TGF-β1 for 24 hours. Western blot analyses were performed for HO-1, Ets-2, and β-actin (to assess loading). Three independent experiments were performed (B and C). Western blot analyses were also performed for Smad2 and Smad3 to assess the degree of shRNA silencing (D).

Discussion

HO-1 is a highly regulated gene by inflammatory stimuli (Alam, et al., 2007), and this regulation occurs predominantly at the transcriptional level (Alam, et al., 2007; Ryter, et al., 2006). Multiple enhancer regions have been identified within the HO-1 5′-flanking sequence, and depending on the specific stimulus and the cell type involved, various transcription factors will interact with their cognate DNA binding domains in the HO-1 promoter to regulate gene transcription (Alam, et al., 2007). Critical regulatory domains are present within a 10 kb region of the mouse HO-1 5′-flanking sequence. Two of the most highly studied and conserved enhancer regions are termed E1 and E2, located at −4 kb and −10 kb upstream from the transcription start site (Alam, et al., 1994; Alam, et al., 1995; Choi, et al., 1996). While differences exist in the promoters of mouse and human HO-1 genes (Sikorski, et al., 2004), and in their regulation depending on specific stimuli, there are also similarities. In the case of LPS stimulation, HO-1 is robustly induced in rodent cells by LPS (Camhi, et al., 1995), and more recently this has also been shown in human monocytes in culture (Rushworth, et al., 2005; Rushworth, et al., 2008). Moreover, the expression of HO-1 is increased in leukocytes of patients with sepsis (Jao, et al., 2005), emphasizing the importance of HO-1 gene regulation.

Additional enhancer regions downstream of E1 and E2 have also been described in the transcriptional regulation of HO-1 (Alam, et al., 2007). An area of focus in our laboratory, and the laboratory of others, has been the role of Ets transcription factors in the regulation of rodent HO-1 (Chung, et al., 2005; Chung, et al., 2006; Deramaudt, et al., 1999; Dhulipala, et al., 2005; Hung, et al., 2010) with binding in the downstream promoter. However, this regulation of HO-1 goes beyond the rodent, as members of the Ets family have been shown to regulate human HO-1 gene expression (Deramaudt, et al., 1999). The Ets family of proteins is also of particular interest because these transcription factors have been reported to be important in the modulation of mammalian immunity (Anderson, et al., 2000; Dittmer, et al., 1998; Zhang, et al., 1995). A balance of Ets family members, including transcriptional activators Ets-2 more than Ets-1, and the repressor Elk-3, regulate the overall transcriptional response of mouse HO-1 during a Gram-negative inflammatory stimulus, E. coli LPS (Chung, et al., 2005; Chung, et al., 2006). Ets proteins interact with Ets binding sites (EBS 1 and 2) located at bp −125 and −93, far from the E1 and E2 enhancer regions. The HO-1 activator Ets-2 binds at EBS2, while the repressor Elk-3 binds more efficiently at EBS1 (Chung, et al., 2005; Chung, et al., 2006). Moreover, we have recently shown that during exposure to a Gram-positive stimulus, S. aureus peptidoglycan, the Ets family member Elk-1 is a potent activator of mouse HO-1, although this effect of Elk-1 was independent of direct DNA binding (Hung, et al., 2010).

The present study shows that an intact EBS2 site is critical for full induction of mouse HO-1 by LPS, and in the presence of a mutated EBS2 site, TGF-β1 does not further suppress LPS-induced HO-1 transactivation (Fig. 6B). Thus, we focused on the EBS2 binding factor Ets-2, and its regulation by TGF-β1. Ets-2 is downregulated by TGF-β1, at both the mRNA and protein level, after LPS stimulation (Fig. 7). The downregulation of Ets-2 does not begin until 12 hours after LPS stimulation, thus helping to explain the delayed suppression of LPS-induced HO-1 by TGF-β1 (Fig. 1A and 1B). Interestingly, the TGF-β1 effector molecule Smad2 is important not only for the downregulation of HO-1, but also for suppression of Ets-2 by TGF-β1 (Fig. 8B). Prior studies have shown that TGF-β1 effector molecules, Smad3 and Smad4, can repress the function of c-Jun, c-Fos, and C/EBPα (Feng, et al., 2005), all of which are putative activators of HO-1 (Alam, et al., 2007). However, to our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the suppressive effect of TGF-β1, via Smad2, on the HO-1 transactivator Ets-2.

While Smad2 is critical for the downregulation of HO-1 and Ets-2 by TGF-β1 during LPS exposure in mouse macrophages (Fig 8B), this does not appear to be the case for Smad3 (Fig. 8C). However, Smad3 may play a role in the regulation of HO-1 by LPS, as HO-1 protein levels are reduced in Smad3 silenced cells (Fig. 8C). In regard to MAP kinase signaling, it does appear that after 15 minutes of LPS exposure, p-SAPK/JNK is transiently increased, and this increase is prevented by TGF-β1 (Fig. 3B). We previously showed that an inhibitor of JNK suppressed HO-1 induced by LPS in macrophages, and that JNK signaling contributed to the expression of Ets-2 (Chung, et al., 2005). Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that suppression of p-SAPK/JNK by TGF-β1 at this early time point may contribute to the downregulation of LPS-induced HO-1 in macrophages.

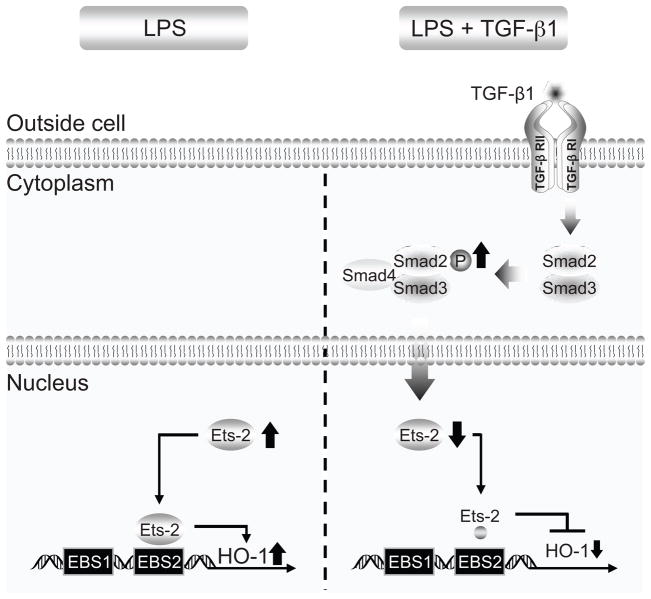

Taken together, these data advance our understanding of the complex regulation of the cytoprotective gene HO-1, not only during an inflammatory stimulus, but also during exposure to the anti-inflammatory mediator TGF-β1. We have previously shown that at the time of LPS stimulation, expression of the repressor Elk-3 and its binding to the EBS1 site is decreased, while expression of the activator Ets-2 and its binding to EBS2 is increased, resulting in marked HO-1 induction in macrophages (Chung, et al., 2005; Chung, et al., 2006). Our current data demonstrate that in the presence of LPS, TGF-β1 is able to suppress HO-1 induction at later time points, and this occurs in part by downregulation of Ets-2, a transactivator of HO-1 via the EBS2 site. Moreover, this ability of TGF-β1 to downregulate HO-1 during LPS exposure is signaling through TGF-βRI, with subsequent phosphorylation of Smad2, whose expression is crucial for both suppression of Ets-2 and HO-1 by TGF-β1. An overview of our findings regarding HO-1 gene regulation by TGF-β1 is provided in Figure 9.

Fig. 9.

TGF-β1 suppression of LPS-induced HO-1 gene expression. The schema illustrates the effect of TGF-β1 on LPS-induced HO-1. HO-1 is transcriptionally induced by LPS in macrophages, and this occurs in part by an increase in Ets-2 expression and binding of Ets-2 to the EBS2 site of the HO-1 promoter (left). However, TGF-β1 is able to suppress the induction of HO-1 by LPS (right). This TGF-β1 response occurs by signaling via TGF-βRI and phosphorylation of Smad2, which results in a downregulation of Ets-2 and less transactivation of the HO-1 promoter, and thus less HO-1 expression.

It is clear that during an inflammatory process like endotoxemia, and also during sepsis, resolution of inflammation is critical for the return to homeostasis (Abraham, et al., 2007; Bone, et al., 1997; Ejima, et al., 2003; Martinez, et al., 2008; Pinsky, 2001). Mediators that promote an anti-inflammatory response, helping to accelerate the resolution of inflammation (Huynh, et al., 2002), also regulate the expression of HO-1, allowing its return to basal levels. The suppression of HO-1 is not limited to TGF-β1, as preliminary data suggest that the anti-inflammatory agent dexamethasone is also able to suppress LPS-induced HO-1 expression (data not shown). In conjunction with prior studies assessing the regulation of HO-1 by Ets family members (Chung, et al., 2005; Chung, et al., 2006; Deramaudt, et al., 1999; Dhulipala, et al., 2005; Hung, et al., 2010), our present data support Ets factors as important mediators of HO-1 gene regulation, allowing tight control over expression of this cytoprotective molecule, not only during an injury response but also during the resolution of injury allowing a return to homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

Cycloheximide blunts the suppression of HO-1 by TGF-β1. Total RNA was extracted from RAW 264.7 cells after exposure to no stimulus, LPS, or LPS+TGF-β1 in the presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) or vehicle (Veh). The expression of HO-1 was then assessed by Northern blot analysis. 18S was used as a control for loading.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Contract grant numbers HL060788, GM053249, and AI061246 to M.A.P.

Contract grant sponsor: Korea Research Foundation; Contract grant numbers KRF-2008-331-C00216 to S.W.C. and BRL-2009-0087350 to H.T.C.

The authors thank Dr. Mark Feinberg for his advice and helpful suggestions.

Literature Cited

- Abraham E, Singer M. Mechanisms of sepsis-induced organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2408–2416. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000282072.56245.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham NG, Kappas A. Heme oxygenase and the cardiovascular-renal system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam J, Cai J, Smith A. Isolation and characterization of the mouse heme oxygenase-1 gene. Distal 5′ sequences are required for induction by heme or heavy metals. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1001–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam J, Camhi S, Choi AMK. Identification of a second region upstream of the mouse heme oxygenase-1 gene that functions as a basal level and inducer-dependent transcriptional enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11977–11984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam J, Cook JL. Transcriptional regulation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene via the stress response element pathway. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:2499–2511. doi: 10.2174/1381612033453730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam J, Cook JL. How many transcription factors does it take to turn on the heme oxygenase-1 gene? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:166–174. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0340TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KL, Perkin H, Surh CD, Venturini S, Maki RA, Torbett BE. Transcription factor PU.1 is necessary for development of thymic and myeloid progenitor-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:1855–1861. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone RC, Grodzin CJ, Balk RA. Sepsis: A new hypothesis for pathogenesis of the disease process. Chest. 1997;112:235–243. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camhi SL, Alam J, Otterbein L, Sylvester SL, Choi AMK. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 gene expression by lipopolysaccharide is mediated by AP-1 activation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:387–398. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.4.7546768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-H, Layne MD, Watanabe M, Yet S-F, Perrella MA. Upstream stimulatory factors regulate aortic preferentially expressed gene-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47658–47663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108678200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi AMK, Alam J. Heme oxygenase-1: Function, regulation, and implication of a novel stress-inducible protein in oxidant-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:9–19. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.1.8679227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SW, Chen Y-H, Perrella MA. Role of Ets-2 in the regulation of heme oxygenase-1 by endotoxin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4578–4584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409125200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SW, Chen Y-H, Yet S-F, Layne MD, Perrella MA. Endotoxin-induced down-regulation of Elk-3 facilitates heme oxygenase-1 induction in macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;176:2414–2420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SW, Liu X, Macias AA, Baron RM, Perrella MA. Heme oxygenase-1-derived carbon monoxide enhances the host defense response to microbial sepsis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:239–247. doi: 10.1172/JCI32730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deramaudt BM, Remy P, Abraham NG. Upregulation of human heme oxygenase gene expression by Ets-family proteins. J Cell Biochem. 1999;72:311–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhulipala PD, Datta PK, Reddy ES, Lianos EA. Differential regulation of the rat heme oxygenase-1 expression by Ets oncoproteins in glomerular mesangial cells. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;146:326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer J, Nordheim A. Ets transcription factors and human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1377:F1–F11. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(97)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejima K, Layne MD, Carvajal IM, Kritek PA, Baron RM, Chen Y-H, vom Saal J, Levy BD, Yet S-F, Perrella MA. Cyclooxygenase-2 deficient mice are resistant to endotoxin-induced inflammation and death. FASEB J. 2003;10:1325–1327. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1078fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejima K, Layne MD, Carvajal IM, Nanri H, Ith B, Yet S-F, Perrella MA. Modulation of the thioredoxin system during inflammatory responses and its effect on heme oxygenase-1 expression. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:569–576. doi: 10.1089/15230860260220067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X-H, Derynck R. Specificity and versatility in TGF-β signaling through Smads. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:659–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.022404.142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles LF, Martin ML, Lelsen L, Stacey KJ, Redd D, Clark YM, Nagamine Y, McMahon M, Hume DA, Ostrowski MC. Persistent activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases p42 and p44 and ets-2 phosphorylation in response to colony-stimulating factor 1/c-fms signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5148–5156. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara N, Kobayashi K. Macrophages in inflammation. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005;4:281–286. doi: 10.2174/1568010054022024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H, Abdollah S, Qiu Y, Cai J, Xu YY, Grinnell BW, Richardson MA, Topper JN, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Wrana JL, Falb D. The MAD-related protein Smad7 associates with the TGFbeta receptor and functions as an antagonist of TGFbeta signaling. Cell. 1997;89:1165–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Kapturczak N, Truong L, Thamilselvan V, Visner GA, Nick HS, Agarwal A. Smad7-dependent regulation of heme oxygenase-1 by transforming growth factor-beta in human renal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40904–40909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung CC, Liu X, Kwon MY, Kang YH, Chung SW, Perrella MA. Regulation of heme oxygenase-1 gene by peptidoglycan involves the interaction of Elk-1 and C/EBPalpha to increase expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298:L870–879. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00382.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh ML, Fadok VA, Henson PM. Phosphatidylserine-dependent ingestion of apoptotic cells promotes TGF-beta1 secretion and the resolution of inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:41–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI11638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jao HC, Lin YT, Tsai LY, Wang CC, Liu HW, Hsu C. Early expression of heme oxygenase-1 in leukocytes correlates negatively with oxidative stress and predicts hepatic and renal dysfunction at late stage of sepsis. Shock. 2005;23:464–469. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000158117.15446.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni AB, Huh C-G, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Ward JM, Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor β1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MO, Wan YY, Sanjabi S, Robertson AK, Flavell RJ. Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:99–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CC, Chiang LL, Lin CH, Shih CH, Liao YT, Hsu MJ, Chen BC. Transforming growth factor-beta1 stimulates heme oxygenase-1 expression via the PI3K/Akt and NF-kappaB pathways in human lung epithelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;560:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines MD, Gibbs PEM. 30 years of heme oxygenase: From a “molecular wrecking ball” to a “mesmerizing” trigger of cellular events. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci. 2008;13:453–461. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning W, Song R, Li C, Park E, Mohesenin A, Choi AMK, Choi ME. TGF-β1 stimulates HO-1 via the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in A549 pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol (Lung Cell Mol Physiol) 2002;283:L1094–L1102. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00151.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein L, Sylvester SL, Choi AMK. Hemoglobin provides protection against lethal endotoxemia in rats: The role of heme oxygenase-1. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:595–601. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.5.7576696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LE, Bach FH, Alam J, Soares M, Tao Lu H, Wysk M, Davis RJ, Flavell RA, Choi AM. Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat Med. 2000;6:422–428. doi: 10.1038/74680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overhaus M, Moore BA, Barbato JE, Behrendt FF, Doering JG, Bauer AJ. Biliverdin protects against polymicrobial sepsis by modulating inflammatory mediators. Am J Physiol (Gastrointest Liver Physiol) 2006;290:G295–G703. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00152.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellacani A, Wiesel P, Sharma A, Foster LC, Huggins GS, Yet S-F, Perrella MA. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 during endotoxemia is downregulated by transforming growth factor-β1. Circ Res. 1998;83:396–403. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.4.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky MR. Sepsis: a pro- and anti-inflammatory disequilibrium syndrome. Contrib Nephrol. 2001;132:354–366. doi: 10.1159/000060100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth SA, Chen XL, Mackman N, Ogborne RM, O’Connell MA. Lipopolysaccharide-induced heme oxygenase-1 expression in human monocytic cells is mediated via Nrf2 and protein kinase C. J Immunol. 2005;175:4408–4415. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth SA, MacEwan DJ, O’Connell MA. Lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 and heme oxygenase-1 protects against excessive inflammatory responses in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2008;181:6730–6737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryter SW, Alam J, Choi AMK. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: From basic science to therapeutic implications. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:583–650. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, Allen R, Sidman C, Proetzel G, Calvin D, Annunziata N, Doetschman T. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-β1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski EM, Hock T, Hill-Kapturczak N, Agarwal A. The story so far: Molecular regulation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F425–441. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00297.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R, Yamamoto Y, McDonagh AF, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science. 1987;235:1042–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.3029864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto T, Wakabayashi Y, Sekiya T, Inoue N, Morita R, Ichiyama K, Takahashi R, Asakawa M, Muto G, Mori T, Hasegawa E, Shizuya S, Hara T, Nomura M, Yoshimura A. Smad2 and Smad3 are redundantly essential for the TGF-beta-mediated regulation of regulatory T plasticity and Th1 development. J Immunol. 2010;185:842–855. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenhunen R, Marver H, Schmid R. Microsomal heme oxygenase, characterization of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6388–6394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R. The enzymatic conversion of heme to bilirubin by microsomal heme oxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;61:748–755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traylor A, Hock T, Hill-Kapturczak N. Specificity protein 1 and Smad-dependent regulation of human heme oxygenase-1 gene by transforming growth factor-β1 in renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F885–F894. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00519.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunawaki S, Sporn M, Ding A, Nathan C. Deactivation of macrophages by transforming growth factor-β. Nature. 1988;334:260–262. doi: 10.1038/334260a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vile GF, Tyrrell RM. Oxidative stress resulting from ultraviolet A irradiation of human skin fibroblasts leads to a heme oxygenase-dependent increase in ferritin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14678–14681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner F, Jain MK, Feinberg MW, Sibinga NES, Pellacani A, Wiesel P, Chin MT, Topper JN, Perrella MA, Lee M-E. Transforming growth factor-β1 inhibition of macrophage activation is mediated via Smad3. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36653–36658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesel P, Foster LC, Pellacani A, Layne MD, Hsieh C-M, Huggins GS, Strauss P, Yet S-F, Perrella MA. Thioredoxin facilitates the induction of heme oxygenase-1 in response to inflammatory mediators. J Biol Chem. 2000a;275:24840–24846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000835200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesel P, Patel AP, DiFonzo N, Marria PB, Sim CU, Pellacani A, Maemura K, LeBlanc BW, Marino K, Doerschuk CM, Yet S-F, Lee M-E, Perrella MA. Endotoxin-induced mortality is related to increased oxidative stress and end-organ dysfunction, not refractory hypotension, in heme oxygenase-1 deficient mice. Circulation. 2000b;102:3015–3022. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.24.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Letterio JJ, Lechleider RJ, Chen L, Hayman R, Gu H, Roberts AB, Deng C. Targeted disruption of SMAD3 results in impaired mucosal immunity and diminished T cell responsiveness to TGF-beta. Embo J. 1999;18:1280–1291. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yet S-F, Pellacani A, Patterson C, Tan L, Folta SC, Foster L, Lee W-S, Hsieh C-M, Perrella MA. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. A link to endotoxic shock. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4295–4301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura A, Wakabayashi Y, Mori T. Cellular and molecular basis for the regulation of inflammation by TGF-β. J Biochem. 2010;147:781–792. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Eddy A, Teng YT, Fritzler M, Kluppel M, Melet F, Bernstein A. An immunological renal disease in transgenic mice that overexpress Fli-1, a member of the Ets family of transcription factor genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6961–6970. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cycloheximide blunts the suppression of HO-1 by TGF-β1. Total RNA was extracted from RAW 264.7 cells after exposure to no stimulus, LPS, or LPS+TGF-β1 in the presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) or vehicle (Veh). The expression of HO-1 was then assessed by Northern blot analysis. 18S was used as a control for loading.