Abstract

Background:

Laparoscopic surgeries are the second most common cause of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), which would cause unexpected delay in hospital discharge. This study intends to compare the efficacy and safety of the combination of ondansetron and dexamethasone with ondansetron alone given as prophylaxis for PONV in adults undergoing elective laparoscopic surgery.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred adult patients undergoing elective laparoscopic surgeries were selected and were randomly divided into 2 groups of 50 each. Group I received 4 mg of ondansetron intravenously (i.v.), whereas Group II received ondansetron 4 mg and dexamethasone 4 mg i.v. just before induction of anesthesia. Postoperatively, the patients were assessed for episodes of nausea, vomiting, and need for rescue antiemetic at intervals of 0–2, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. Postoperative pain scores and time for the first analgesic dose were also noted.

Results:

Results were analyzed statistically. Complete response defined as no nausea or emesis and no need for rescue antiemetic during first 24 h, was noted in 76% of patients who received ondansetron alone, while similar response was seen in 92% of patients in combination group. Rescue antiemetic requirement was less in combination group (8%) as compared with ondansetron group.

Conclusion:

Combination of ondanserton and dexamethasone is more effective in preventing post operative nausea vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery than ondansetron alone.

Keywords: Dexamethasone, laparoscopic surgery, ondansetron, postoperative nausea vomiting

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic surgeries stand second in terms of incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), which in turn is a cause of unexpected delay in hospital discharge. The patients frequently list pain, nausea, and vomiting as their most important perioperative concern.[1] With the change in the emphasis from an inpatient to outpatient hospital and office-based medical/surgical enhancement, there has been increased interest in the “big little problem”[2] of PONV.

Nausea and vomiting have been associated for many years with the use of general anesthetics for surgical procedures. Extensive descriptions of the phenomenon were elaborated by John Snow. He suspected that movement shortly after operation may have triggered vomiting.[3]

The etiology and consequences of PONV are complex and multifactorial with patients’ medical- and surgery-related factors. A thorough understanding of these factors, as well as the neuropharmacology of multiple emetic receptors (dopaminergic, muscarinic, cholinergic, opioid, histamine, and serotonin) and physiology (cranial nerves VIII, IX, X, and gastrointestinal reflex) relating to PONV is necessary to manage PONV.[1]

There are at least 3 kinds of vomiting, the first of which is attributed to anesthetics, such as ether, the second to reflex responses, such as pain or ovarian surgery, and the last to opioids. Early studies reported incidence of PONV as high as 75%–80% after opioid premedication and prolonged ether anesthesia.[4]

Over the years, numerous drugs have been used in the management of PONV. Various techniques, including olive oil and insulin glucose infusion[5] and addition of atropine to morphine premedication were reported to be effective.[6]

Persistent nausea and vomiting may result in dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and delayed discharge. It can cause tension on suture lines, venous hypertension, and increased bleeding under skin flaps. It exposes the subject to increased risk of pulmonary aspiration of vomitus.[7] Esophageal rupture, subcutaneous emphysema, and bilateral pneumothorax are additional complications. The annual cost of PONV in the United States is thought to approach a billion dollars.[8]

The newest class of antiemetics used for prevention and treatment of PONV are serotonin (5HT3) receptor antagonists—ondansetron, granisetron, tropisetron, and dolasetron. These antiemetics do not have the adverse effects of the older, traditional antiemetics.

The available antiemetics, such as 5HT3 antagonists, are effective in very low doses. Thus, cost could be lowered and drug side effects prevented when given as prophylaxis, lowering the economic burden imposed due to complications and increased medical care resulting from PONV.

Aims

To assess the (i) efficacy of prophylactic antiemetic drug therapy, (ii) safety and benefits of using combination, and (iii) the requirement of rescue antiemetic in the postoperative period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This randomized controlled trial was done after taking approval from the ethics committee. Written informed consent was taken from all the 100 American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status 1 and 2 patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery. They were then randomly divided into Group I and Group II with sealed envelope technique of 50 patients in each group. Group I received 4 mg of ondansetron intravenously (i.v.), whereas Group II received ondansetron 4 mg and dexamethasone 4 mg i.v. just before the induction of anesthesia.

Inclusion criteria

Patients of ASA Grade I and II undergoing laparoscopic surgery.

Patients between 18 and 55 years of age.

Patients weighing between 30 and 75 kg.

Exclusion criteria

Patients belonging to ASA Grade III and IV.

Patients who had received opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, and antiemetic agents during the previous 24 h.

Patients with a history of PONV.

Patients with a history of motion sickness and previous PONV.

Methods

A day prior to surgery, preoperative evaluation of the patients was done. Necessary preoperative investigations based on the diagnosis were done. All the patients received Tab diazepam 10 mg at night and 5 mg in the morning of surgery and also Tab ranitidine 150 mg on the night of the surgery. Patients were kept nil per oral from midnight.

After shifting the patient to the operation theatre, normal saline infusion was started. Preinduction monitors were connected, which included electrocardiography, noninvasive blood pressure monitoring, and oxygen saturation through pulse oxymetry. The patients were then given study medication based on groups they belonged

The patients were then preoxygenated for 3 min and premedicated with 0.2 mg/kg of midazolam and 1 mg/kg of pethidine. Anesthesia was then induced with inj thiopental sodium to the loss of eyelash reflex neuromuscular blockade achieved, which was achieved with inj vecuronium, 0.1 mg/kg after 3 min of assisted ventilation, endotracheal intubation was done with an appropriate-sized endotracheal tube. General anesthesia was maintained with air in oxygen and halothane 0.5%–1% with controlled ventilation through closed circuit. Postinduction monitoring included end-tidal carbon dioxide and temperature. After completion of the surgery, the residual paralysis was antagonised with inj. neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and atropine 0.02 mg/kg. The patients were then transported to the recovery room after extubation and later to the ward after confirming that there was adequate level of conciousness and intact reflexes. The incidence of PONV was recorded within the first 24 h of surgery at intervals of 0–2, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. Episodes of PONV were identified by spontaneous complaints by the patients or by direct questioning.

Complete response was defined as the absence of any nausea or vomiting and no need for rescue antiemetic during the whole observation period. Rescue antiemetic was provided with inj. ondansetron 4 mg i.v. in case of patient complaining of nausea or had vomiting. Pain was measured using a 11-point numerical visual analog scale (VAS) with 0=no pain and 10 = severe pain. Rescue analgesia was provided on patients’ demand with inj. diclofenac sodium 75 mg i.m. to counter the pain. The results were analyzed statstically, evaluated, and compared between the 2 groups [Tables 1–3].

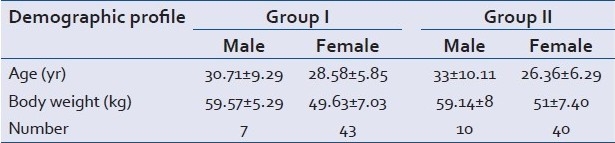

Table 1.

Demographic profile of study population

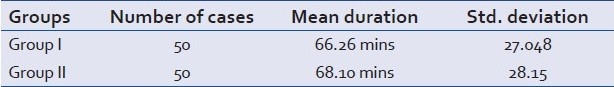

Table 3.

Duration of surgery in the study population

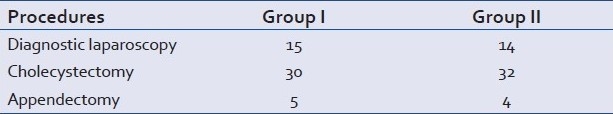

Table 2.

Different types of surgical procedures in study population

RESULTS

Demographic data, type of surgery and duration of surgery among the groups are demonostrated in Tables 1–3 respectively.

Postoperative data

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

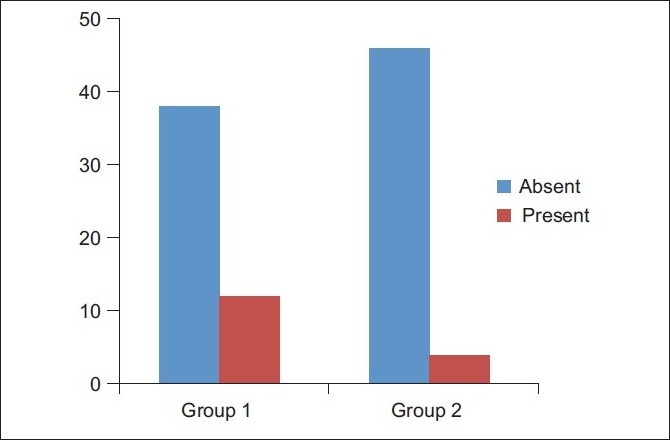

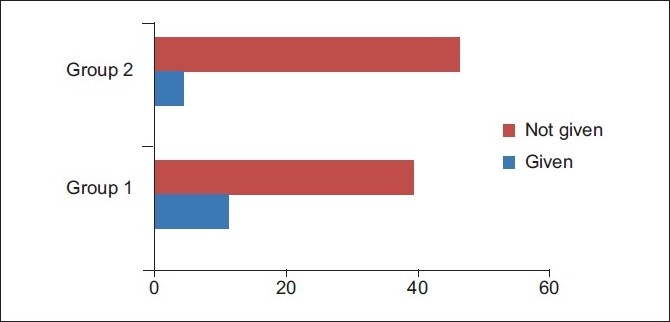

PONV was present in 12 of 50 patients in Group I, whereas 4 of 50 patients had PONV in Group II. This is shown in Figure 1. It was found to be statistically significant (P<0.029).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the patients by groups and nausea/vomiting

Rescue antiemetic

In this study, ondansetron 4 mg was used as rescue antiemetic in both the groups. In Group I, of the 12 patients who complained of PONV, 11 patients received rescue antiemetic, whereas 1 patient who had mild nausea did not need rescue antiemetic. In Group II, all the 4 patients who complained of PONV received rescue antiemetic. This was found to be statistically significant (P<0.050) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Distribution of the patients by groups and administration of rescue antiemetic

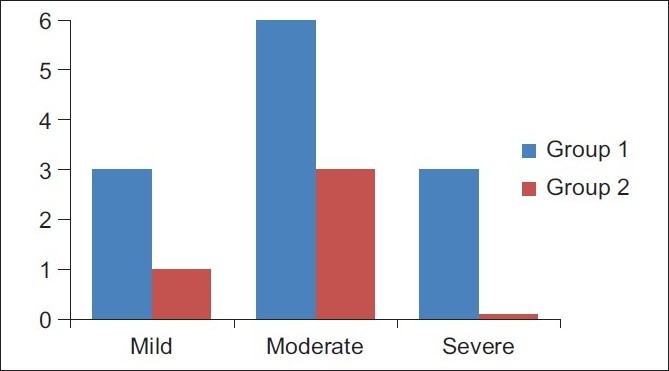

Incidence of pain and PONV

Although intraoperatively all the patients received inj pethidine for analgesia depending on the type and duration of the procedure, the pain scores (assessed by VAS) were less severe in Group II. Of the 12 patients who complained of PONV in Group I, 3 had mild pain, 6 had moderate pain, while the remaining 3 had severe pain. This can be compared to pain scores among patients who had PONV in Group II, 1 patient had mild pain, while other 3 had moderate pain. None had severe pain. This can be correlated to the fact that pain is one of the factors inducing PONV, although it was found to be statistically insignificant, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The incidence of pain and postoperative nausea and vomiting

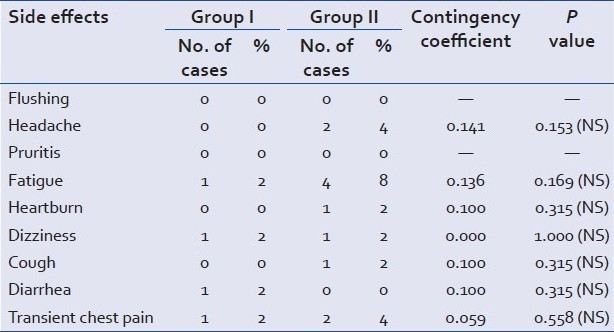

Side effects

The incidence of side effects in both the groups is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Number of cases and percentage of patients with side effects in both the groups with results of contingency coefficient tests

DISCUSSION

PONV is one of the main complaints in patients undergoing surgery under general anesthesia. The incidence of PONV in patients undergoing laparoscopy ranges from 40% to 75%. It is the one of the most important factors that determines the length of hospital stay after ambulatory anesthesia. In fact its contribution to patient dissatisfaction is such that over 70% of patients considered avoidance of PONV to be very important.[9]

Numerous factors can affect PONV, such as age, gender, obesity, motion sickness, history of PONV, duration of the procedure, anesthetic technique, use of opioids, and pain. In our study, the majority of these factors (age, gender, weight, duration of the procedure, anesthetic technique, and medication) were not significant among both the study groups.

The selection of drug dosages was based on the previous work that demonstrated that these doses were effective.[10]

Ondansetron, a selective 5 HT3 receptor antagonist, has been shown to be effective in the prevention and treatment of PONV in many studies.

Role of steroids as antiemetics was established in 1980, and dexamethasone as an antiemetic was introduced later. Many studies have shown that dexamethasone alone or in combination with other antiemetics used prophylactically prevents PONV.[10] The mechanism of action of corticosteroids is unknown; however, there have been some suggestions, such as central/peripheral inhibition of production of 5HT, central inhibition of synthesis of prostaglandins, or changes in permeability of the blood–brain barrier to serum proteins.

It was shown that dexamethasone was most effective when adminstered at the time of induction of anesthesia. As for ondansetron, it was suggested that in operative procedures lasting more than 2 h, it might be relevant to administer the drug toward the end of the surgery as the half-life of ondansetron is approximately 3.5-4 h in adults.[9] Since the mean duration of the procedure in our study was about an hour, we assumed that the timing of antiemetic combination before induction would not affect the outcome.

A complete response to the prophylaxis of antiemetic therapy was defined as no nausea or vomiting and no need for rescue antiemetic during the 24 h observation period postoperatively. It was duly noted. In our study, the complete repsonse occurred in 76% of the cases in ondansetron group and 92% in ondansetron and dexamethasone group. This is comparable to the study conducted by Panda et al.[11]

In our study, the incidence of complete response is comparable to other studies conducted by Biswas et al,[12] in patients undergoing laparoscopic tubal ligation and Elhakim et al,[13] in pateints undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomies.This may be explained due to variation in the type and duration of laparoscopic procedures in our study as compared to a single type of laparoscopic procedures in those studies.

In our study, 12 cases in Group I had complaints of PONV of which 11 cases (22%) needed rescue antiemetic. This can be compared with 4 cases (8%) in Group II who had complaints of PONV and all of them needed rescue antiemetic. The need for rescue antiemetic is more in Group I (22%) than in Group II (4%), which is comparable to a study conducted by Elhakim et al.[13]

In the present study, 2 patients who had been treated for PONV within the first 2 h in Group II with rescue antiemetic had persistent nausea and vomiting later on. Of the 2 cases, one required a second dose of antiemetic, whereas the other had only one episode of nausea and vomiting after treatment and did not require a repeat dose.

The incidence and severity of pain was less in Group II than in Group I. This probably reflects the strong anti-inflammatory action of dexamethasone, which has been shown to decrease postoperative pain. This is comparable to the study conducted by Elhakim et al.[13]

Considering the side effects profile of ondansetron and dexamethasone, both the drugs are well tolerated. A single dose of dexamethasone is considered safe. Two cases had minor side effects that included headache, heartburn, and transient chest pain. These side effects were statistically insignificant.

CONCLUSION

PONV is one of the most distressing side effects of anesthesia and surgery, which is even higher after laparoscopic surgeries. The quest for more effective antiemetic drugs without the potential for sedative or extrapyramidal side effects has led to the recent development of a relatively new class of drugs, 5HT3 antagonists, of which ondansetron is a prototype.[14] Although 5HT3 antagonists are potent antiemetics, no single drug has been successful in effectively controlling PONV. This has led to a number of studies investigating the efficacy of combination of various antiemetics with an assumption that using a combination of antiemetics acting on different receptors can further reduce the incidence of PONV.[15]

In our study we have compared the efficacy of ondansetron 4 mg alone with the combination of ondansetron 4 mg and dexamethasone 8 mg i.v. given prophylactically just before induction of anesthesia in adult patients undergoing elective laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia.

It has been concluded from this study that the combination of ondansetron 4 mg with dexamethasone 4 mg is more effective than ondansetron 4 mg alone in preventing PONV. Both the monotherapy and the combination therapy have a very good safety profile and are well tolerated among patients. The combination therapy has a better patient response in preventing PONV.

Limitations

Not all laparoscopic surgeries were included in the study.

The high incidence of PONV after laparoscopic surgeries may justify the use of prophylactic antiemetic and hence we did not believe it to be ethical to include a placebo group.

We did not address the issues of economy and surrogate variables, such as hospital discharge times, expenses incurred toward treating established PONV, and sequelae of PONV.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the faculty of the Department of Anesthesiology, Dhulikhel Hospital, for their support and those who contributed significantly in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kovac AL. Prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Drugs. 2000;59:213–43. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapur PA. The big “little problem”. Anesth Analg. 1991;73:243–5. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrew PL. Physiology of nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:2–19. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.supplement_1.2s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerman J. Surgical and patient factors involved in post operative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:24–32. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.supplement_1.24s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Islam S, Jain PN. Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV): A review article. Indian J Anaesth. 2004;48:253–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowbotham DJ. Current management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:46–59. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.supplement_1.46s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watcha MF, White PF. White.Postoperative nausea and vomiting – its etiology, treatment and prevention. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apfel CC, Stoecklein K, Lipfert P. PONV: A problem of inhalational anesthesia? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2005;19:485–500. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller RD. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. Millers Anesthesia; p. 2294. (2597). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajeeva V, Bharadwaj N, Balia YK, Dhaliwal LK. Comparison of ondansetron with ondansetron and dexamethasone in prevention of PONV in diagnostic laparoscopy. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:40–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03012512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panda NB, Bharadwaj N, Kapoor P, Chari P, Panda NK. Prevention of nausea and vomiting after middle ear surgery; combination of ondansetron and dexamethasone is the right choice. J Otolaryngol. 2004;33:88–92. doi: 10.2310/7070.2004.02091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biswas BN, Rudra A, Mandal SK. Comparison of ondansetron, dexamethasone, ondansetron with dexamethasone and placebo in prevention of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic tubal ligation. (640, 642).J Indian Med Assoc. 2003;101:638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elhakim M, Nafie M, Mahmoud K, Atef A. Dexamethasone 8 mg in combination with ondansetron 4 mg appears to be the optimal dose for the prevention of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Anesth. 2002;49:922–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03016875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russel D, Kenny GN. 5HT3 antagonist in postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:63–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.supplement_1.63s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gan TJ. Postoperative nausea and vomiting—Can it be eliminated? JAMA. 2002;287:1233–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]