Abstract

Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) and intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) are increasingly recognized as potential complications in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. ACS and IAH affect all body systems, most notably the cardiac, respiratory, renal, and neurologic systems. ACS/IAH affects blood flow to various organs and plays a significant role in the prognosis of the patients. Recognition of ACS/IAH, its risk factors and clinical signs can reduce the morbidity and mortality associated. Moreover, knowledge of the pathophysiology may help rationalize the therapeutic approach. We start this article with a brief historic review on ACS/IAH. Then, we present the definitions concerning parameters necessary in understanding ACS/IAH. Finally, pathophysiology aspects of both phenomena are presented, prior to exploring the various facets of ACS/IAH management.

Keywords: Abdominal compartment syndrome, intra-abdominal hypertension, intra-abdominal pressure

INTRODUCTION

It was not until 2006 that the World Society on Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (WSACS, www.wsacs.org) established consensus definitions for intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) and for abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). Thus, “the intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) is the steady-state pressure concealed within the abdominal cavity”, while “ACS is a sustained IAP >20 mmHg [with or without abdominal perfusion pressure (APP) <60 mmHg] that is associated with a new organ dysfunction/failure”.[1] We try to briefly overview key aspects of ACS and abdominal hypertension in this article. It includes an historical review, a definitions summary, a pathophysiologic outline as well as management suggestions.

HISTORICAL ASPECTS OF ABDOMINAL COMPARTMENT SYNDROME

Presenting in brief the history of the ACS is not an easy task; numerous problems arise, among which, the most important is the lack of consensus among scientists studying the history of this condition. When learning how to write an article on the history of medicine, the first advice given to students is never to use the words “first”, “discover” or “founder”, in an attempt to avoid disagreements from other researchers. Well, in this article, this advice should necessarily be forgotten, since the history of ACS is relatively new, meaning it appeared after publication in scientific journals came into our lives; and as we all know, he who publishes first, is the first to be acknowledged!

The compartment syndrome was initially described in limbs by Richard Volkmann in 1811 in an article entitled “Die ischemischen Muskellähmungen und –Kontrakturen”.[2] He described a condition in which increased pressure within closed fascial space reduces blood perfusion of the muscles and leads to a contracture.

In 1863, Etienne-Jules Marey presented for the first time the relationship between increased IAP and respiratory function, in a book he published entitled “Physiologie médicale de la circulation du sang”, noting that the effects of respiration on the thorax are the inverse of those present in the abdomen.[3] Marey's conclusion was reinforced in 1870, by Paul Bert, who published a book entitled “Leçons sur la physiologie de la respiration” where he described elevation of IAP on inspiration and descent of the diaphragm, based on experiments on animals, measuring thoracic and abdominal pressures with tubes from the trachea and the rectum, respectively.[4]

As far as the measurement of the IAP is concerned, numerous authors experimented in the best way to do it. In 1872, the German physician Schatz used a balloon tube connected to a manometer, measuring pressure within the uterus, while 1 year later, Wendt (also a German) measured it through the rectum, and in 1875, Oderbrecht measured it within the urinary bladder.[5]

In 1911, H. Emerson experimented in dogs and proved that contraction of the diaphragm raises the IAP, while anesthesia and muscle paralysis decrease the IAP, and that increased IAP may cause death due to cardiac failure. His most important note was that cardiovascular collapse associated with “distension of the abdomen with gas or fluid, as in typhoid fever, ascites, or peritonitis” is caused by “overloading the resistance in the splanchnic area” and that “relief of the laboring heart is constantly seen after removal of ascitic fluid”.[5] Emerson was actually the scientist who built the foundations of the clinical and experimental research on IAP in the 20th century.

Some decades elapsed after Emerson's findings without important research on the field. In 1940, W.H Ogilvie wrote in Lancet an important article concerning open abdomen after war wounds.[6] In 1948, R.E. Gross acknowledged the importance of avoiding abdominal closure under excessive tension,[7] but it was in 1951 that M.G. Baggot brought new light in the matter of the importance of IAP. He identified abdominal dehiscence as the main factor increasing IAP and recommended avoiding closure under tension and leaving the abdomen open.[8]

The first description of the ACS was made in 1984 by I. Kron, P.K. Harman and S.P. Nolan: “The direct measurement of IAP through an indwelling transurethral bladder catheter has become a simple and reliable diagnostic technique for us (…) IAPs below 20 mmHg in a postoperative patient in the absence of rapid blood loss or renal insufficiency are an indication for continued observation. An IAP above 25 mmHg in a postoperative patient with an adequate blood volume and a low urinary output is an indication for abdominal re-exploration and decompression”.[9] There is an erroneous belief that Kron et al. first used the term ACS. The term though, was not introduced until 1989 by Fietsam et al.: “In four patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms increased IAP developed after repair. It was manifested by increased ventilatory pressure, increased central venous pressure, and decreased urinary output associated with massive abdominal distension not due to bleeding. This set of findings constitutes an intra-abdominal compartment syndrome caused by massive interstitial and retroperitoneal swelling”.[10]

The history of the ACS is a typical one. First was the matter of identifying the importance of the increased abdominal pressure; then was finding the best way to measure it and understanding its effect on patients. Finally, it was not until the 1980s that the physicians identified the ACS and searched for the best methods to treat it. After 1990, the interest in the ACS was raised; nowadays, more than 100 scientific articles on the subject are published in medical journals per year. In 2004, the WSACS was founded and the interest on this condition took a formal and concise character.

DEFINITIONS, RISK FACTORS, AND MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUES

As mentioned above, compartment syndrome exists when increased pressure in a closed anatomic space threatens the viability of the tissue within this compartment. Excessive intra-compartmental hypertension leads to devastating abnormalities in diverse organs and systems, many of which are readily discoverable with routine monitoring in the critical care unit, and all of which are related to decreased preload, increased afterload, and extrinsic compression, with decreased end-organ oxygen delivery and utilization.[11] The resulting pressure-volume deregulation syndrome is known as the ACS. Therefore, ACS is not a disease, but a syndrome of symptoms and signs that can have multiple causes.[12]

Definitions

Intra-abdominal pressure

The abdomen can be considered a closed box with walls both rigid (costal arch, spine, and pelvis) and flexible (abdominal wall and diaphragm). The elasticity of the walls and the character of its contents determine the pressure within the abdomen at any given time.[1,13] Since the abdomen and its contents can be considered as relatively non-compressive and primarily fluid in character, behaving in accordance with Pascal's law, the IAP measured at one point may be assumed to represent the IAP throughout the abdomen (with the rare exception of upper ACS[14]). It is therefore defined as a steady-state pressure concealed within the abdominal cavity. IAP increases with inspiration (diaphragmatic contraction) and decreases with expiration (diaphragmatic relaxation).[6] It is also directly affected by the volume of the solid organs or hollow viscera (which may be either empty or filled with air, liquid or fecal matter), the presence of ascites, blood or other space-occupying lesions (such as tumors or gravid uterus), and the presence of conditions that limit expansion of the abdominal wall (such as burn or third-space edema).[13]

Normal IAP ranges from sub-atmospheric to 0 mmHg. Certain physiological conditions such as morbid obesity and pregnancy may be associated with chronic IAP elevations.[13] In the critically ill, IAP is frequently elevated above the patient's normal baseline. Recent abdominal surgery, sepsis, organ failure, the need for mechanical ventilation and changes in body position are all associated with elevations of IAP. Normal IAP is approximately 5–7 mm Hg in critically ill patients.[15,16]

Abdominal perfusion pressure

APP is calculated as the mean arterial pressure (MAP) minus the IAP. APP has been proposed as a more accurate predictor of visceral perfusion and a potential endpoint for resuscitation.[17] By considering both arterial inflow (MAP) and restrictions to venous outflow (IAP), APP has been demonstrated to be superior to either parameter alone in predicting patient survival from IAH and ACS.[17] APP values of at least 60 mmHg have been associated with improved survival in patients with IAH and ACS.[17]

Filtration gradient

The renal filtration gradient (FG) is the mechanical force across the glomerulus and equals the difference between the glomerular filtration pressure (GFP) and the proximal tubular pressure (PTP). In the presence of IAH, PTP may be assumed equal to IAP and thus GFP can be estimated as MAP minus 2IAP. Thus, changes in IAP will have a greater impact upon renal function and urine production than that caused by changes in MAP. As a result, oliguria is one the first visible signs of IAH.[17,18]

Intra-abdominal hypertension

In healthy individuals, normal IAP is <5–7 mmHg.[19] The upper limit of IAP is generally accepted to be 12 mmHg by the WSACS, reflecting the expected increase in normal pressure from clinical conditions that exert external pressure to the peritoneal envelope or diaphragm, including obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[20] In contrast, IAH is defined as a sustained or repeated pathologic increase in IAP >12 mmHg.[21]

According to the level of IAP, IAH is graded as follows:

Grade I: IAP 12–15 mmHg

Grade II: IAP 16–20 mmHg

Grade III: IAP 21–25 mmHg

Grade IV: IAP >25 mmHg

IAH may also be subclassified into one of four groups according to the duration[22]: Hyperacute representing elevations in IAP that last but for a few seconds or minutes as a result of laughing, straining, coughing, sneezing, defecation or physical activity,[23] acute with IAH developing over a period of hours and is seen primarily in surgical patients as a result of trauma or intra-abdominal hemorrhage, subacute with IAH occurring over a period of days and is the form most encountered in medical patients, and chronic in which IAH develops over a period of months (i.e., pregnancy) or years (i.e., morbid obesity, intra-abdominal tumor, peritoneal dialysis, chronic ascites or cirrhosis) and may place patients at risk for developing either acute or subacute IAH when critically ill.[13]

Abdominal compartment syndrome

Critical IAP in the majority of patients appears to reside between 10 and 15 mmHg.[16] It is at this pressure that reductions in microcirculatory blood flow and the initial development of ACS occur. ACS represents the natural progression of end-organ dysfunction, and develops if IAH is not recognized appropriately.[21] Classically, ACS is defined by the triad: (a) pathologic state caused by an acute increase in IAP >20–25 mmHg, (b) presence of adverse effects on end-organ function, and (c) abdominal decompression has beneficial effects.[17]

ACS may be classified as primary, secondary, or recurrent, according to its cause and duration. Primary ACS (surgical or abdominal ACS) is characterized by the presence of acute or subacute IAH resulting from an intra-abdominal cause (abdominal trauma or post-abdominal surgery). Secondary ACS (medical or extra-abdominal) is characterized by the presence of subacute or chronic IAH resulting from conditions requiring massive fluid resuscitation, such as septic shock or major burns. Recurrent ACS (tertiary) represents the resurgence of ACS following resolution of an earlier episode.[17]

Risk factors

Originally thought to be a disease of the traumatically injured, IAH and ACS have now been recognized to occur in a wide variety of patient populations. Numerous risk factors have been suggested, and they are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Risk factors for intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome

The duration of IAH, in conjunction with the acuity of onset, is commonly of greater prognostic value than the absolute increase in IAP. Pre-existing comorbidities, such as chronic renal failure, pulmonary disease, or cardiomyopathy, play an important role in aggravating the effects of elevated IAP and may reduce the threshold of IAH that causes clinical manifestation of ACS.[17] Chronically increased IAP is also largely limiting the marge of increase that IAP can achieve without developing ACS.[13]

Massive fluid resuscitation has been considered a major contributor for the development of ACS in critically ill patients.[24] In patients with the inflammatory response syndrome and increased vascular permeability, massive fluid resuscitation leads to increased IAP due to fluid sequestration and formation of ascites. The administration of large amounts of fluid also causes bowel edema, with ingurgitation of the mesenteric vessels and lymphatic system. IAH decreases venous return, creating a vicious cycle of more intestinal swelling and greater increase in IAP.[24]

Burns can lead to ACS by several mechanisms. Circumferential burns of the abdominal area with abdominal wall edema and eschar formation can cause extrinsic compression of the abdomen. Large burns can lead to ischemic enterocolitis secondary to elevated mesenteric vascular resistance, which is attributed to the release of vasoactive substances (angiotensin II and vasopressin), and inflammatory mediators from burned tissue. In addition, the increase in IAP may be because of ascites and bowel edema secondary to massive fluid resuscitation, exacerbated by the generalized increase in capillary permeability.[25]

Given the broad range of potential etiological factors and the significant associated morbidity and mortality of IAH/ACS, a high index of suspicion and low threshold for IAP measurement appears appropriate for any patient possessing any of these risk factors. WSACS has recommended screening patients upon intensive care unit (ICU) admission and in the presence of new or progressive organ failure.[26]

TECHNIQUES TO MEASURE INTRA-ABDOMINAL PRESSURE

Clinical examination for the diagnosis of ACS has been shown to be highly unreliable with sensitivity and positive predictive value of around 40–60%, thus making it a poor diagnostic tool.[27] The use of abdominal perimeter is equally inaccurate. Radiological investigation with plain radiography of the chest or abdomen, and abdominal ultrasound or computer tomography (CT) are insensitive to the presence of increased IAP. However, they can be indicated to illustrate the cause of IAH (bleeding, hematoma, ascites or abscess) and may offer clues for management (paracentesis or drainage of collections).[14] The diagnosis of IAH/ACS is therefore dependent upon the accurate and frequent measurement of IAP. IAP monitoring is a cost-effective, safe, and an accurate tool for identifying the presence of IAH and guiding resuscitative for ACS.[28] Given the favorable risk-benefit profile of IAP monitoring and the significant associated morbidity and mortality of IAH/ACS, it is recommended that (a) if two or more risk factors for IAH/ACS are present, a baseline IAP measurement should be obtained (Grade 1B) and (b) if IAH is present, serial IAP measurements should be performed throughout the patient's critical illness (Grade 1C).[26]

The IAP can be measured directly or indirectly, either intermittently or continuously. Direct measurement can be obtained by an intraperitoneal catheter installed for ascites drainage or peritoneal dialysis, an intraperitoneal pressure transducer and during laparoscopic surgery.[29] Indirect methods for measuring IAP include intravesical, gastric, rectal, uterine, inferior vena cava, and airway pressure measurements.[30] Because of its simplicity and low cost, IAP measurement by the intravesical route has been considered as the gold standard.[26] The technique relies on the fact that the bladder has a very compliant wall and when infused with a small amount of saline, it can function as a passive reservoir and transducer of IAP. Changes in IAP are reflected as changes in intravesical pressure.[16] Measurement should be obtained with the patient in the supine position as the body position can alter IAP and bladder pressures.[31] Although most commonly, IAP has been measured intermittently, methods for continuous IAP measurement have been proposed.[30]

Bladder pressure measurements are not feasible in some patients. Those patients with bladder trauma, neurogenic bladders, outflow obstruction and tense pelvic hematomas will require alternative methods of IAP measurement. A nasogastric IAP monitor has been developed as well.[32] Measurement through the stomach has some advantages; it avoids problems associated with creating a hydrostatic fluid column in the bladder and is easier for continuous measurement.

Pathophysiology of intra-abdominal hypertension/abdominal compartment syndrome

Increased IAP not only compromises regional blood flow in the peritoneal cavity, but also exerts adverse effects on organs and systems outside the abdomen. Increased IAP is manifested as a graded response described as IAH, leading progressively to ACS, a not graded “all or nothing” response during which organ viability is seriously threatened.[1]

In 2004, the WSACS was founded by leading international experts and currently serves as a scientific resource and a forum for establishing the concept of IAH and ACS in everyday clinical practice.[1,26,33,34] The recognition of IAH as an independent prognostic factor for critically ill patients[35] will be gradually embedded in the “goal-directed” approach used in the ICU and will alter the decision-making process. In this review, the pathophysiologic aspects leading to IAH and IAP are elucidated with an aim to a better understanding of both the phenomena.

The introduction of laparoscopic surgery in the 1990s was followed by extensive experimental and clinical study of IAH and ACS and led to an increased appreciation of their pathophysiologic sequelae.[14,36,37] These effects include the directly affected intra-abdominal organs, as well as indirectly adjacent or remote systems and organs.

Cardiovascular system

IAH displaces cephalad the diaphragm and increases intrathoracic pressure (ITP). This is called abdomino-thoracic transmission and has been shown to be 20–80%, with ITP generally assumed to be IAP/2. Increased ITP significantly reduces venous return, resulting in reduced cardiac output and simultaneously compresses directly the heart, reducing ventricular compliance and contractility. Systemic vascular resistances are increased due to compression of the aorta, the systemic and pulmonary vasculature (increased afterload) and the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pathway.[38–41] As a result of these effects and the shunting of blood away from the abdomen, MAP initially rises and eventually normalizes or decreases.[42] These effects occur at levels of IAP as low as 10 mmHg,[43] while hypovolemic patients manifest reduced cardiac output at even lower IAPs.[38] Similarly, the application of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) aggravates the cardiovascular effects of IAH.[44–46] On the contrary, volume administration increases the preload temporarily improving the hemodynamics.[47]

Due to abdomino-thoracic transmission, traditional intracardiac filling pressures [central venous pressure (CVP) and pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP)] are erroneously elevated during IAH and cannot be used as cardiac preload parameters. Both measurements are the sum of intravascular pressure and ITP and thus are no longer reflective of true intravascular volume. Therefore, it is more accurate to use volumetric indices such as right ventricular end diastolic volume index and global end diastolic volume index.[41,48–52] Preload responsiveness to volume intravenous load is better assessed using dynamic parameters such as pulse pressure and stroke volume variation.[53–55] If volumetric or dynamic parameters are not available and traditional filling pressures have to be used for hemodynamic monitoring, transmural pressures should be calculated by deleting ITP (or IAP/2), as follows:[42,56]

Transmural PAOP = PAOP – IAP/2

Transmural CVP = CVP – IAP/2.

Concerning venous blood return from the lower extremities, femoral venous pressure is markedly increased, as a result of a parallel rise of the inferior vena cava pressure due to IAH.[57–59] Normalization of IAP restores femoral blood flow, but has been associated with reported pulmonary embolism, resembling to ischemia-reperfusion models.[60]

Pulmonary system

IAH results in an extrinsic compression of the pulmonary parenchyma, attributable to the cephalic displacement of the diaphragm, resulting from intra-abdominal volume augmentation.[13] This situation leads to respiratory dysfunction, which is characterized by: alveolar atelectasis, decreased oxygen transport across the pulmonary capillary membrane and intrapulmonary shunt; reduced capillary blood flow, decreased carbon dioxide excretion and increased alveolar dead space; arterial hypoxemia and hypercarbia. Both inspiratory and mean airway pressures increase significantly, while tidal volume and pulmonary compliance are reduced.[61,62] This secondary acute respiratory distress syndrome may require a change in ventilator settings: (a) ideally PEEP should counteract IAP, (b) transmural plateau pressures should be used (Pplat – IAP/2) and maintained under 35 cmH2O, and (c) due to risk of lung edema, extravascular lung water index should be measured.[63]

Urinary system

IAH-induced renal dysfunction manifests as oliguria at an IAP of 15 mmHg and as anuria at 30 mmHg in the presence of normovolemia and normal initial renal function.[64,65] This is due to reduced renal perfusion, compression of the renal parenchyma and the renal vein, all three leading to reduced microcirculation in the renal cortex and functioning glomeruli, resulting in glomerular and tubular dysfunction and subsequent reduction in urine production and output.[18,66–69] Also, plasma renin activity, aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone levels increase significantly.[65,70] Moreover, FG is the mechanical force across the glomerulus and is equal to the difference between GFP and the PTP.[71] GFP is equal to renal perfusion pressure and is calculated as MAP minus IAP, while PTP is equal to the IAP. This means that

FG = GFP – PTP = (MAP – IAP) – IAP = MAP – 2 × IAP.

Therefore, prerenal azotemia associated with IAH-induced renal dysfunction is responsive to neither volume expansion nor dopaminergic agents and loop diuretics, but rather dramatically improves by reducing promptly and appropriately the increased IAP.[10,63,72,73]

Increased IAP also affects the urinary bladder. Experimentally, IAH has been found to induce biochemical (increased malondialdehyde levels), structural (damage of the lamina propria, epithelium and serosa) and contractility (acethylocholine potentiated contractions) changes of the urinary bladder.[74]

Gastrointestinal system

The gastrointestinal system shows great sensitivity to alterations of IAP. Mainly two functions are altered: (a) the mucosal-barrier function (influencing both intermucosal nutrient flow and bacterial translocation) and (b) the gastrointestinal motility.

Specifically, bowel mucosa seems to be quite sensitive to elevations of IAP and is associated with: (a) reduction of mesenteric blood flow, which can occur at IAP of only 10 mmHg,[75] (b) diminished blood flow to all abdominal organs (except the adrenals that excrete catecholamines[76]), (c) compression of mesenteric veins, with subsequent intestinal edema and ischemia, (d) decreased intramucosal perfusion and pH, increased permeability and loss of intestinal mucosal barrier,[77,78], and finally, (e) bacterial translocation, sepsis and multiorgan failure.[67] These changes are pronounced after several insults of IAH-induced ischemia-reperfusion and serve as the second insult in the two-hit model of the multiorgan dysfunction syndrome.[79,80] These effects were termed as acute bowel injury and acute intestinal distress syndrome (AIDS).[81] The key parameter used as a resuscitation goal is the maintenance of APP above 60 mmHg.[17]

Concerning gastrointestinal motility, a relationship was established between the increased IAP and decreased electrical and mechanical motor activity of the small intestine.[82,83] Increased IAP may inhibit contractile responses and may lead to structural alterations through an ischemia-reperfusion model.[84]

Hepatobiliary system

The liver is particularly susceptible to damage during IAH. Blood flow in the hepatic artery and veins and the portal circulation is reduced even in “small” elevations of IAP of 10 mmHg, resulting in a compensatory gastroesophageal collateral blood flow to the azygos vein. IAP elevation leads to increased hepatocyte apoptosis and enhanced hepatocyte proliferation, suggesting a liver repair response.[85] Additionally, altered mitochondrial function, glucose metabolism and decreased lactate clearance are the physiologic effects of IAH.[86–91] Furthermore, other conditions such as liver failure, decompensated chronic liver disease and liver transplantation are complicated by the development of IAH and ACS.[92,93]

Nervous system

Several studies show increased intracranial pressure (ICP) as a result of IAP elevation,[47,94–98] in the context of poly-compartment syndrome. The most known proposed mechanisms include: (a) the decreased lumbar venous plexus blood flow due to functional obstruction by the increased pressure of inferior vena cava, which results in decreased absorption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the region of the lumbar cisterna and subsequent increase of CSF pressure transmitted intracranially,[99] and (b) the increased ITP which increases jugular venous pressure, further impeding cerebral venous outflow (functional obstruction), decreasing cerebral blood flow and increasing the intracranial blood volume, which increases ICP.[47,96] As a consequence of increased ICP, cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP = MAP – IAP) is reduced. These effects significantly complicate polytrauma patients with concomitant abdominal and head injuries, in which frequent IAP, ICP and neurologic monitoring and avoidance of hypervolemia are essential preventive measures undertaken.[95,100,101]

Abdominal wall

IAH directly reduces abdominal wall blood flow by a compression effect leading to local ischemia and edema. This phenomenon is probably true for all muscles constituting the abdominal wall. In particular, abdominis rectis sheath blood flow decreases to 58% of baseline at an IAP of only 10 mmHg, further worsening at 40 mmHg.[102] Abdominal wall edema can develop secondary to shock and fluid resuscitation, resulting in decreased abdominal wall compliance, which further exacerbates IAH.[103] These effects may contribute to the increased non-infectious and infectious complications (impaired wound healing, dehiscence, herniation and necrotizing fasciitis) often seen in patients whose abdomens are closed under tension.[58,102]

Modalities of treatment

Prevention is of paramount importance in “treating” IAH and ACS. While 45% are multifactorial, fluid overload coupled with intra-abdominal sepsis, bowel obstruction, and hemorrhage are the main individual causes leading to ACS. Earlier diagnosis and treatment of intra-abdominal sepsis would result in less fluid administration and prevention of tissue edema.[104,105] Excellence in technical surgery coupled with appropriate correction of coagulopathy would decrease postoperative hematoma and bleeding. While trauma surgeons have embraced prophylactic abdominal decompression, this procedure has not been popular among general surgeons[106], and it is probably underutilized. The use of AbdoVAC (KCI Medical, San Antonio, TX, USA) and other proprietary devices facilitates re-exploration in patients who need decompression. Optimizing clinical care would reduce adverse outcomes, which has been demonstrated in areas at the periphery of acute general surgery, such as pelvic fracture, where early hemorrhage control reduces the mortality significantly and in the process reduces the prevalence of ACS.[107,108]

The precise management of IAH remains somewhat clouded. Aggressive non-operative intensive care support is critical to prevent the complications of ACS. This involves careful monitoring of the cardiorespiratory system and the renal function and aggressive intravascular fluid replacement.[43] Excessive fluid resuscitation, however, will actually add to the problem.[105]

In patients with Grades III-IV IAH, the treating team should locate the underlying problem and provide interim hemodynamic support until the focus of bleeding, sepsis, or obstruction has been dealt with. For patients who require damage control surgery, interventional radiology should be integrated into the strategy for achieving hemostasis. Not all patients require surgical exploration or aggressive fluid resuscitation, and often percutaneous drainage of an abscess or ascites is all that is required.[109] Diagnosis of tertiary peritonitis requires an aggressive diagnostic approach, with abdominal CT scanning and prompt drainage of pus. Detection of postoperative hemorrhage requires good nursing care and clear pathways for communication between junior staff and consultants. Ideally, frontline ward and ICU staff should have regular performance evaluations to ensure a reduction in errors, which are fairly common. Apart from the direct association between sepsis and bleeding, IAH exerts negative effects on colon healing and visceral blood flow.[80,110]

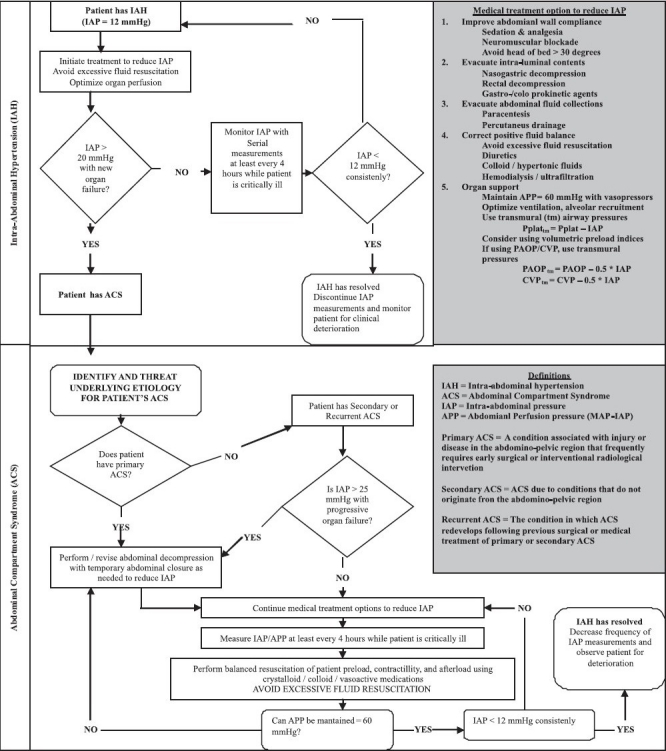

WSACS published Web evidence-based guidelines (www.wsacs.org). Recommendations are classified as either strong recommendations (Grade 1) or weak suggestions (Grade 2). Quality of evidence is ranked as high (Grade A), moderate (Grade B), or low (Grade C). Given the wide variety of patients who may develop IAH/ACS, not one management strategy can be uniformly applied to all patients. While surgical decompression is commonly considered the only treatment, non-operative medical management strategies play a vital role in the prevention and treatment of IAH-induced organ dysfunction and failure. Appropriate IAH/ACS management is based upon the following four principles: serial monitoring of IAP

optimization of systemic perfusion and organ function

institution of specific medical interventions to reduce IAP and

prompt surgical decompression for refractory IAH.

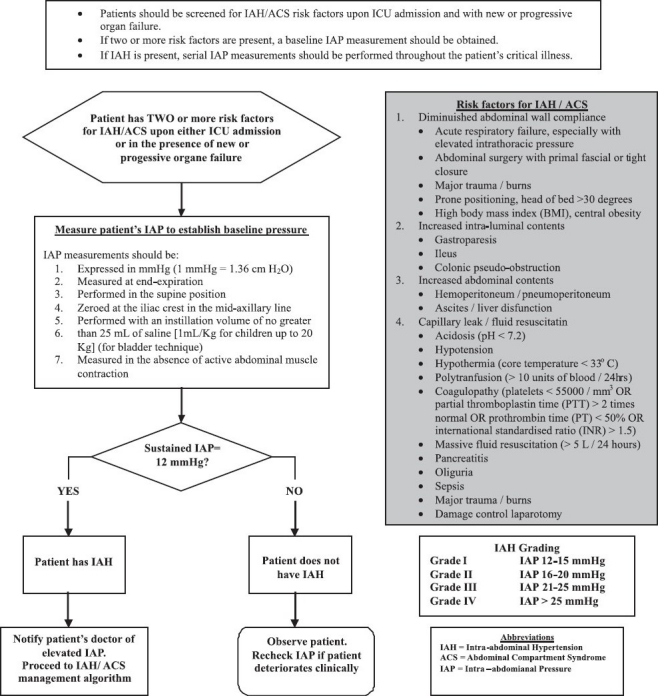

Patients should be screened for IAH/ACS risk factors upon ICU admission and in the presence of new or progressive organ failure (Grade 1B). Independent risk factors for IAH/ACS are presented in Table 1. If two or more risk factors for IAH/ACS are present, a baseline IAP measurement should be obtained (Grade 1B). If IAH is present, serial IAP measurements should be performed throughout the patient's critical illness (Grade1C). APP should be maintained above 50–60 mmHg in patients with IAH/ACS (Grade 1C). Serial IAP measurements are necessary to guide resuscitation of patients with IAH/ACS.

No recommendations can be made at this time concerning pain, agitation and ventilator dys-synchrony. Accessory muscle use during breathing may all lead to increased abdominal muscle tone. This increased muscle activity can increase IAP. Sedation and analgesia can reduce muscle tone and decrease IAP to less detrimental levels. While such therapy would appear prudent, no prospective trials have been performed evaluating the benefits and risks of sedation and analgesia in IAH/ACS.

A brief trial of neuromuscular blockade (NMB) may be considered in selected patients with mild to moderate IAH while other interventions are performed to reduce IAP (Grade 2C). Diminished abdominal wall compliance due to pain, tight abdominal closures and third-space fluid can increase IAP to detrimental levels. The potential beneficial effects of NMB in reducing abdominal muscle tone must be balanced against the risks of prolonged paralysis. NMB is unlikely to be an effective therapy for patients with severe IAH or the patient who has already progressed to ACS.

The potential contribution of body position in elevating IAP should be considered in patients with moderate to severe IAH or ACS (Grade 2C). Head of bed elevation can significantly increase IAP compared to supine positioning, especially at higher levels of IAH. Such increases in IAP become clinically significant (increase >2 mmHg) when the patient's head of bed elevation exceeds 20°. Both air and fluid within the hollow viscera can raise IAP and lead to IAH/ACS. Nasogastric and/or rectal drainage, enemas and even endoscopic decompression can probably reduce IAP. Prokinetic motility agents such as erythromycin, metoclopromide, or neostigmine can aid in evacuating the intraluminal contents and decreasing the size of the viscera. Nevertheless, insufficient evidence is currently available to confirm the benefit of such therapies in IAH/ACS.

Fluid resuscitation volume should be carefully monitored to avoid over-resuscitation in patients at risk for IAH/ACS (Grade 1B). Hypertonic crystalloid and colloid-based resuscitation should be considered in patients with IAH to decrease the progression to secondary ACS (Grade 1C). Fluid resuscitation and “early goal-directed therapy” are cornerstones of critical care management. Excessive fluid resuscitation is an independent predictor of IAH/ACS and should be avoided. The use of goal-directed hemodynamic monitoring should be considered to achieve appropriate fluid resuscitation. Diuretic therapy, in combination with colloid, may be considered to mobilize third-space edema following initial resuscitation and once the patient is hemodynamically stable. Continuous hemofiltration/ultrafiltration may be an appropriate intervention rather than continuing to volume load and increase the likelihood of secondary ACS. These therapies have yet to be subjected to prospective clinical study in IAH/ACS patients.

Percutaneous catheter decompression should be considered in patients with intraperitoneal fluid, abscess, or blood, who demonstrate symptomatic IAH or ACS (Grade 2C). Paracentesis represents a less invasive method for treating IAH/ACS due to free fluid, ascites, air, abscess, or blood. Percutaneous catheter insertion under ultrasound guidance allows ongoing drainage of intraperitoneal fluid and may help avoid the need for open abdominal decompression in selected patients with secondary ACS.

Surgical decompression should be performed in patients with ACS that is refractory to other treatment options (Grade 1B). Presumptive decompression should be considered at the time of laparotomy in patients who demonstrate multiple risk factors for IAH/ACS (Grade 1C). Surgical abdominal decompression has long been the standard treatment for the patient who develops ACS. It represents a life-saving intervention when a patient's IAH becomes refractory to medical treatment options and organ dysfunction and/or failure is evident. Most patients tolerate primary fascial closure within 5–7 days if decompressed before significant organ failure develops. In Figure 1 is summarized the IAH assessment algorithm and in Figure 2 is summarized the management algorithm for IAH/ACS as proposed by WSAC.[1] Management options for the “open abdomen” include split-thickness skin grafting, cutaneous advancement flap (“skin only”) closure, and vacuum-assisted closure techniques (with or without retention sutures) bogota bag, zipper system, sandwich method, synthetic mesh, occlusive dressing under suction, and silicone rubber sheets.[111–117] Each of these techniques is associated with major shortcomings, including bowel fistula formation, retraction of the abdominal fascia, and intestinal adherence to the prosthesis.[118,119] Based on our experience using these techniques, some considerations emerged. Bogota bag is sutured to the abdominal wall or to the fascia, and it needs to be changed frequently until the underlying problem in the abdomen is solved. Peritoneal fluid cannot be quantified because of the frequent leaks of the wound edges. The use of Bogota bag is associated with a high incidence of skin excoriation and enteroatmospheric fistulas. Recently, an alternative method of Bogota bag was proposed. Instead of conventional plastic bags, a human chorioamniotic membrane prepared under sterile conditions is used.[120] With this method, it is believed that serosal erosion and fistula formation can be prevented in patients undergoing open abdominal surgery.

Figure 1.

Intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) assessment algorithm (Adapted from Intensive Care Med 2006;32:1722–32 & 2007;33:951-62)

Figure 2.

Intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) / abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) management algorithm (Adapted from Intensive Care Med 2006;32:1722–32 & 2007;33:951-62)

Zipper fasteners are less adherent to the underlying viscera; their use requires suturing of the prosthetic material to the abdominal wall tissues. Management of peritoneal fluid remains a problem unless a drainage system is incorporated. Closure of the skin only can result in leaks of peritoneal fluid, which saturates dressings and potentially allows contamination of the peritoneal cavity. Once zipper mechanism is used, there is serious difficulty for its repeated application.

Sandwich technique proved simple in construction and is well-tolerated in the critical care environment. However, the use of sutures on the fascial edges seems to increase IAP, since recurrence of ACS occurred. Furthermore, when abdomen is left open for long enough, a fascial necrosis was observed.

Placement of polypropylene mesh in temporary closure of the abdomen has been well documented.[121,122] It has been used with and without a zipper mechanism to allow for sequential abdominal re-explorations. Underlying viscera may adhere to the mesh and become injured during subsequent re-exploration. The mesh, if left for long enough in place, may erode into the bowel. Repetitive suturing of biosynthetic material to fascial edges damages the fascia and may be a causative factor of fascial necrosis development.

Occlusive dressing under suction is the closest method to Vacuum Assisted Closure (VAC) technique. Technical problems were rare. Peritoneal fluid leaks were repaired at the bedside by application of additional adhesive drape over the leak site. This technique was abandoned because of the easiest application of VAC (KCI International, San Antonio, TX, USA) device in patients with open abdomen.

The VAC technique is a sutureless closure that avoids mechanical damage to the tissues of the abdominal wall, leaving them intact for subsequent closure. This method lessens the risk of bowel injury at the time of re-exploration. Peritoneal fluid losses can be quantified and replaced as needed. Application of the adhesive-backed drape stabilizes the dressing in place and seals the wound edges, preventing passage of fluid in or out of the wound. The surrounding skin is protected and skin soilage is minimized. Wound infection and tissue necrosis was not observed in patients with vacuum packs in place. Skin excoriation from peritoneal fluid was minimized. Timing of re-exploration is based on patient stability and intra-abdominal pathology. The decision to continue with open abdomen management is made at the time of each reoperation and based on the need for early planned re-exploration of the peritoneal cavity for additional surgical procedures, or when conventional closure of the abdominal wall would result in unacceptable abdominal wall tension or increased IAP. However, the resulting open abdomen is a complex clinical problem. Modern techniques and technologies are now available that allow for improved management of the open abdomen and the progressive reduction of the fascial defect. Additionally, lot of progress has to be made concerning morbidity and cost of care.[123] Indeed, recent evidence indicates that a large proportion of patients treated with open abdomen can now be closed within the initial hospitalization. VAC associated morbidity mainly resides into difficult fascial closure and herniation. Multiple techniques have been introduced to obtain fascial closure, such as split-thickness skin grafts to cover the exposed bowel,[124] mesh (prosthetic or biologic) approximation of the fascia,[119,125,126] sequential fascial closure,[127] abdominal reapproximation anchor (ABRA).[128] component separation[129,130] and anterior rectus abdominis sheath turnover flap.[131]

It is essential that general and trauma surgeons understand the core principles underlying the need for and management of the open abdomen. Toward this goal, an Open Abdomen Advisory Panel was established to identify core principles in the management of the open abdomen and to develop a set of recommendations based on the best available evidence. This review presents the principles and recommendations identified by the Open Abdomen Advisory Panel and provides brief case studies for the illustration of these concepts.[132] A comprehensive evidence-based management strategy that includes early use of an open abdomen in patients at risk significantly improves survival from IAH/ACS. This improvement is not achieved at the cost of increased resource utilization and is associated with an increased rate of primary fascial closure.[133] However, prospective trials to identify the optimal management technique have yet to be performed.

CONCLUSIONS

Multiple and profound physiologic abnormalities are caused by ACS/IAH, both within and outside the abdomen. Early recognition of increased IAP is primordial in the management. In order for this to occur, monitoring of IAP, either intermittent or continuous, is necessary to all patients presenting with risk factors. Additionally, understanding of the pathophysiology of ACS/IAH is of prime importance when trying to apply patient-tailored treatments. Moreover, surgical intervention should be indicated by IAH and not delayed until ACS is clinically apparent. We believe that every treating physician involved with patient candidates of developing ACS/IAH should be at least informed on the multiple aspects of the phenomena. WSACS (www.wsacs.org) provides, for this reason, an excellent place of ACS/IAH experts meeting point as well as useful updates concerning ACS/IAH.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malbrain ML, Cheatham ML, Kirkpatrick A, Sugrue M, Parr M, De Waele J, et al. Results from the International Conference of Experts on Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. I. Definitions. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1722–32. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volkmann R. On ischemic muscle paralysis and contraction. Centralblatt für Chirurgie. 1881;51:801–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marey E-J. Paris: A Delahaye; 1863. Medical physiology on the blood circulation; pp. 284–93. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bert P. Paris: JP Baillière;; 1870. Lessons on the physiology of respiration. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emerson H. Intra-abdominal pressures. Arch Intern Med. 1911;7:754–84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogilvie WH. The late complication of abdominal war wounds. Lancet. 1940;2:253–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross RE. A new method for surgical treatment of large omphaloceles. Surgery. 1948;24:277–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baggot MG. Abdominal blowout. Curr Res Anesth Analg. 1951;30:295–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kron IL, Harman PK, Nolan SP. The measurement of intra-abdominal pressure as a criterion for abdominal re-exploration. Ann Surg. 1984;199:28–30. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198401000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fietsam R, Jr, Villalba M, Glover JL, Clark K. Intra-abdominal compartment syndrome as a complication of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Am Surg. 1989;55:396–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maerz L, Kaplan LJ. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S212–5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore EE, Burch JM, Franciose RJ, Offner PJ, Biffl WL. Staged physiologic restoration and damage control surgery. World J Surg. 1998;22:1184–90. doi: 10.1007/s002689900542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papavramidis TS, Duros V, Michalopoulos A, Papadopoulos VN, Paramythiotis D, Harlaftis N. Intra-abdominal pressure alterations after large pancreatic pseudocyst transcutaneous drainage. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Laet IE, Malbrain M. Current insights in intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. Med Intensiva. 2007;31:88–99. doi: 10.1016/s0210-5691(07)74781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez NC, Tenofsky PL, Dort JM, Shen LY, Helmer SD, Smith RS. What is normal intra-abdominal pressure? Am Surg. 2001;67:243–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lerner SM. Review article: the abdominal compartment syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol. 2008;28:377–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheatham ML, White MW, Sagraves SG, Johnson JL, Block EF. Abdominal perfusion pressure: A superior parameter in the assessment of intra-abdominal hypertension. J Trauma. 2000;49:621–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200010000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugrue M, Jones F, Deane SA, Bishop G, Bauman A, Hillman K. Intra-abdominal hypertension is an independent cause of postoperative renal impairment. Arch Surg. 1999;134:1082–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.10.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugrue M. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:333–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000170505.53657.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert DM, Marceau S, Forse RA. Intra-abdominal pressure in the morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1225–32. doi: 10.1381/096089205774512546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlotti A, Carvalho W. Abdominal compartment syndrome: A review. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10:115–20. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31819371b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malbrain ML, Deeren D, De Potter TJ. Intra-abdominal hypertension in the critically ill: it is time to pay attention. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:156–71. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000155355.86241.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grillner S, Nilsson J, Thorstensson A. Intra-abdominal pressure changes during natural movements in man. Acta Physiol Scand. 1978;103:275–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balogh Z, Moore FA, Moore EE, Biffl WL. Secondary abdominal compartment syndrome: A potential threat for all trauma clinicians. Injury. 2007;38:272–9. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson M, Dziewulski P. Severe gastrointestinal haemorrhage and ischemic necrosis of the small bowel in a child with 70% full-thickness burns: A case report. Burns. 2001;27:763–6. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheatham ML, Malbrain ML, Kirkpatrick A, Sugrue M, Parr M, De Waele J, et al. Results from the International Conference of Experts on Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. II. Recommendations. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:951–62. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugrue M, Bauman A, Jones F, Bishop G, Flabouris A, Parr M, et al. Clinical examination is an inaccurate predictor of intra-abdominal pressure. World J Surg. 2002;26:1428–31. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malbrain ML. Abdominal pressure in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2000;6:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schachtrupp A, Henzler D, Orfao S, Schaefer W, Schwab R, Becker P, et al. Evaluation of a modified piezoresistive technique and a water-capsule technique for direct and continuous measurement of intra-abdominal pressure in a porcine model. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:74–50. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000198526.04530.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malbrain M. Different techniques to measure intra-abdominal pressure (IAP): Time for a critical re-appraisal. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:357–71. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shear W, Rosner MH. Acute kidney dysfunction due to the abdominal compartment syndrome. J Nephrol. 2006;19:556–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed SF, Britt RC, Collins J, Weireter L, Cole F, Britt LD. Aggressive surveillance and early catheter-directed therapy in the management of intra-abdominal hypertension. J Trauma. 2006;61:1359–65. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000245975.68317.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Waele JJ, Cheatham ML, Malbrain ML, Kirkpatrick AW, Sugrue M, Balogh Z, et al. Recommendations for research from the International Conference of Experts on Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Acta Clin Belg. 2009;64:203–9. doi: 10.1179/acb.2009.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheatham ML. Nonoperative management of intraabdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. World J Surg. 2009;33:1116–22. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malbrain ML, Chiumello D, Pelosi P, Bihari D, Innes R, Ranieri VM, et al. Incidence and prognosis of intraabdominal hypertension in a mixed population of critically ill patients: a multiple-center epidemiological study. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:315–22. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000153408.09806.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheatham ML. Abdominal compartment syndrome: pathophysiology and definitions. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:10. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-17-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malbrain ML, De laet IE. Intra-abdominal hypertension: Evolving concepts. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30:45–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kashtan J, Green JF, Parsons EQ, Holcroft JW. Hemodynamic effect of increased abdominal pressure. J Surg Res. 1981;30:249–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(81)90156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ridings PC, Bloomfield GL, Blocher CR, Sugerman HJ. Cardiopulmonary effects of raised intra-abdominal pressure before and after intravascular volume expansion. J Trauma. 1995;39:1071–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199512000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richardson JD, Trinkle JK. Hemodynamic and respiratory alterations with increased intra-abdominal pressure. J Surg Res. 1976;20:401–4. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(76)90112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malbrain ML, Cheatham ML. Cardiovascular effects and optimal preload markers in intra-abdominal hypertension. In: Vincent JL, editor. Yearbook of intensive care and emergency medicine. Berlin: Springer; 2004. pp. 519–43. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheatham M, Malbrain M. Cardiovascular implications of elevated intraabdominal pressure. In: Ivatury R, Cheatham M, Malbrain M, Sugrue M, editors. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Georgetown: Landes Bioscience; 2006. pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon RJ, Friedlander MH, Ivatury RR, DiRaimo R, Machiedo GW. Hemorrhage lowers the threshold for intra-abdominal hypertension-induced pulmonary dysfunction. J Trauma. 1997;42:398–403. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelosi P, Ravagnan I, Giurati G, Panigada M, Bottino N, Tredici S, et al. Positive end-expiratory pressure improves respiratory function in obese but not in normal subjects during anesthesia and paralysis. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1221–31. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199911000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sugrue M, D’Amours S. The problems with positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) in association with abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) J Trauma. 2001;51:419–20. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200108000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sussman AM, Boyd CR, Williams JS, DiBenedetto RJ. Effect of positive end-expiratory pressure on intra-abdominal pressure. South Med J. 1991;84:697–700. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bloomfield GL, Ridings PC, Blocher CR, Marmarou A, Sugerman HJ. A proposed relationship between increased intraabdominal, intrathoracic, and intracranial pressure. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:496–503. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199703000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheatham ML, Block EF, Nelson LD, Safcsak K. Superior predictor of the hemodynamic response to fluid challenge in critically ill patients. Chest. 1998;114:1226–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.4.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheatham ML, Nelson LD, Chang MC, Safcsak K. Right ventricular end-diastolic volume index as a predictor of preload status in patients on positive end-expiratory pressure. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1801–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schachtrupp A, Graf J, Tons C, Hoer J, Fackeldey V, Schumpelick V. Intravascular volume depletion in a 24-hour porcine model of intra-abdominal hypertension. J Trauma. 2003;55:734–40. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000042020.09010.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michard F, Alaya S, Zarka V, Bahloul M, Richard C, Teboul JL. Global end-diastolic volume as an indicator of cardiac preload in patients with septic shock. Chest. 2003;124:1900–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michard F, Teboul JL. Predicting fluid responsiveness in ICU patients: A critical analysis of the evidence. Chest. 2002;121:2000–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.6.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duperret S, Lhuillier F, Piriou V, Vivier E, Metton O, Branche P, et al. Increased intra-abdominal pressure affects respiratory variations in arterial pressure in normovolaemic and hypovolaemic mechanically ventilated healthy pigs. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:163–71. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malbrain ML, De Laet I. Functional haemodynamics during intra-abdominal hypertension: What to use and what not use. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52:576–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barnes GE, Laine GA, Giam PY, Smith EE, Granger HJ. Cardiovascular responses to elevation of intra-abdominal hydrostatic pressure. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:R208–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.248.2.R208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheatham ML. Abdominal compartment syndrome: pathophysiology and definitions. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:10. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-17-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodale RL, Beebe DS, McNevin MP, Boyle M, Letourneau JG, Abrams JH, et al. Hemodynamic, respiratory, and metabolic effects of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1993;166:533–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watson RA, Howdieshell TR. Abdominal compartment syndrome. South Med J. 1998;91:326–32. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199804000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacDonnell SP, Lalude OA, Davidson AC. The abdominal compartment syndrome: the physiological and clinical consequences of elevated intra-abdominal pressure. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:419–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ranieri VM, Brienza N, Santostasi S, Puntillo F, Mascia L, Vitale N, et al. Impairment of lung and chest wall mechanics in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: role of abdominal distension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1082–91. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.4.97-01052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gattinoni L, Pelosi P, Suter PM, Pedoto A, Vercesi P, Lissoni A. Acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease.Different syndromes? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:3–11. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9708031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Quintel M, Pelosi P, Caironi P, Meinhardt JP, Luecke T, Herrmann P, et al. An increase of abdominal pressure increases pulmonary edema in oleic acid-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:534–41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200209-1060OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richards WO, Scovill W, Shin B, Reed W. Acute renal failure associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure. Ann Surg. 1983;197:183–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198302000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shenasky JH. The renal hemodynamic and functional effects of external counterpressure. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1972;134:253–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Doty JM, Saggi BH, Blocher CR, Fakhry I, Gehr T, Sica D, et al. Effects of increased renal parenchymal pressure on renal function. J Trauma. 2000;48:874–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200005000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Doty JM, Saggi BH, Sugerman HJ, Blocher CR, Pin R, Fakhry I, et al. Effect of increased renal venous pressure on renal function. J Trauma. 1999;47:1000–3. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199912000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sugrue M, Hallal A, D’Amours S. Intra-abdominal pressure hypertension and the kidney. In: Ivatury R, Cheatham M, Malbrain M, Sugrue M, editors. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Georgetown (TX): Landes Bioscience; 2006. pp. 119–28. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sugrue M, Buist MD, Hourihan F, Deane S, Bauman A, Hillman K. Prospective study of intra-abdominal hypertension and renal function after laparotomy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:235–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kirkpatrick AW, Colistro R, Laupland KB, Fox DL, Konkin DE, Kock V, et al. Renal arterial resistive index response to intraabdominal hypertension in a porcine model. Crit Care Med. 2006;35:207–13. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000249824.48222.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bloomfield GL, Blocher CR, Fakhry IF, Sica DA, Sugerman HJ. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure increases plasma renin activity and aldosterone levels. J Trauma. 1997;42:997–1004. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199706000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ulyatt DB. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure. Aust Anaes. 1992;10:108–14. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luca A, Feu F, García-Pagán JC, Jiménez W, Arroyo V, Bosch J, et al. Favorable effects of total paracentesis on splanchnic hemodynamics in cirrhotic patients with tense ascites. Hepatology. 1994;20:30–3. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(94)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith JH, Merrell RC, Raffin TA. Reversal of postoperative anuria by decompressive celiotomy. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:553–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Unsal MA, Imamoğlu M, Cay A, Kadioglu M, Aydin S, Ulku C, et al. Acute alterations in biochemistry, morphology and contractility of rat isolated urinary bladder via increased intra-abdominal pressure. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61:179–87. doi: 10.1159/000091273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Friedlander MH, Simon RJ, Ivatury R, DiRaimo R, Machiedo GW. Effect of hemorrhage on superior mesenteric artery flow during increased intra-abdominal pressures. J Trauma. 1998;45:433–89. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199809000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Caldwell CB, Ricotta JJ. Changes in visceral blood flow with elevated intraabdominal pressure. J Surg Res. 1987;43:14–20. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reintam A, Parm P, Kitus R, Starkopf J, Kern H. Gastrointestinal Failure score in critically ill patients: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2008;12:R90. doi: 10.1186/cc6958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sugrue M, Jones F, Janjua KJ, Deane SA, Bristow P, Hillman K. Temporary abdominal closure: A prospective evaluation of its effects on renal and respiratory physiology. J Trauma. 1998;45:914–21. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199811000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Diebel LN, Dulchavsky SA, Brown WJ. Splanchnic ischemia and bacterial translocation in the abdominal compartment syndrome. J Trauma. 1997;43:852–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199711000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Diebel LN, Dulchavsky SA, Wilson RF. Effect of increased intra-abdominal pressure on mesenteric arterial and intestinal mucosal blood flow. J Trauma. 1992;33:45–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199207000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Malbrain ML, De Laet I. AIDS is coming to your ICU: Be prepared for acute bowel injury and acute intestinal distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1565–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Khripun AI, Ettinger AP, Chadaev AP, Tat’kov SS. Changes in the contractile and bioelectrical activities of the rat small intestine under increased intra-abdominal pressure. Izv Akad Nauk Ser Biol. 1997;5:596–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dodds WJ, Hogan WJ, Stewart ET, Stef JJ, Arndorfer RC. Effects of increased intra-abdominal pressure on esophageal peristalsis. J Appl Physiol. 1974;37:378–83. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Unsal MA, Imamoglu M, Kadioglu M, Aydin S, Ulku C, Kesim M, et al. The acute alterations in biochemistry, morphology, and contractility of rat-isolated terminal ileum via increased intra-abdominal pressure. Pharmacol Res. 2006;53:135–41. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mogilner JG, Bitterman H, Hayari L, Brod V, Coran AG, Shaoul R, et al. Effect of elevated intra-abdominal pressure and hyperoxia on portal vein blood flow, hepatocyte proliferation and apoptosis in a rat model. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2008;18:380–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Diebel LN, Wilson RF, Dulchavsky SA, Saxe J. Effect of increased intra-abdominal pressure on hepatic arterial, portal venous, and hepatic microcirculatory blood flow. J Trauma. 1992;33:279–82. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199208000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wendon J, Biancofiore G, Auzinger G. Intraabdominal hypertension and the liver. In: Ivatury R, Cheatham M, Malbrain M, Sugrue M, editors. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Georgetown (TX): Landes Bioscience; 2006. pp. 138–43. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cade R, Wagemaker H, Vogel S, Mars D, Hood-Lewis D, Privette M, et al. Hepatorenal syndrome.Studies of the effect of vascular volume and intraperitoneal pressure on renal and hepatic function. Am J Med. 1987;82:427–38. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90442-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nakatani T, Sakamoto Y, Kaneko I, Ando H, Kobayashi K. Effects of intra-abdominal hypertension on hepatic energy metabolism in a rabbit model. J Trauma. 1998;44:446–53. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199803000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luca A, Cirera I, García-Pagán JC, Feu F, Pizcueta P, Bosch J, et al. Hemodynamic effects of acute changes in intra-abdominal pressure in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:222–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Burchard KW, Ciombor DM, McLeod MK, Slothman GJ, Gann DS. Positive end expiratory pressure with increased intraabdominal pressure. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;161:313–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Biancofiore G, Bindi ML, Boldrini A, Consani G, Bisà M, Esposito M, et al. Intraabdominal pressure in liver transplant recipients: incidence and clinical significance. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:547–9. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Biancofiore G, Bindi ML, Romanelli AM, Boldrini A, Consani G, Bisà M, et al. Intra abdominal pressure monitoring in liver transplant recipients: a prospective study. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:30–6. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1552-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Deeren DH, Dits H, Malbrain ML. Correlation between intra-abdominal and intracranial pressure in nontraumatic brain injury. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1577–81. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2802-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Josephs LG, Este-McDonald JR, Birkett DH, Hirsch EF. Diagnostic laparoscopy increases intracranial pressure. J Trauma. 1994;36:815–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199406000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bloomfield GL, Ridings PC, Blocher CR, Marmarou A, Sugerman HJ. Effects of increased intra-abdominal pressure upon intracranial and cerebral perfusion pressure before and after volume expansion. J Trauma. 1996;40:936–41. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199606000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Citerio G, Vascotto E, Villa F, Celotti S, Pesenti A. Induced abdominal compartment syndrome increases intracranial pressure in neurotrauma patients: A prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1466–71. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Citerio G, Berra L. Intraabdominal hypertension and the central nervous system. In: Ivatury R, Cheatham M, Malbrain M, Sugrue M, editors. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Georgetown (TX): Landes Bioscience; 2006. pp. 144–56. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Halverson AL, Barrett WL, Iglesias AR, Lee WT, Garber SM, Sackier JM. Decreased cerebrospinal fluid absorption during abdominal insufflation. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:797–800. doi: 10.1007/s004649901102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Irgau I, Koyfman Y, Tikellis JI. Elective intraoperative intracranial pressure monitoring during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 1995;130:1011–3. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430090097028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Joseph DK, Dutton RP, Aarabi B, Scalea TM. Decompressive laparotomy to treat intractable intracranial hypertension after traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2004;57:687–93. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000140645.84897.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Diebel L, Saxe J, Dulchavsky S. Effect of intra-abdominal pressure on abdominal wall blood flow. Am Surg. 1992;58:573–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mutoh T, Lamm WJ, Embree LJ, Hildebrandt J, Albert RK. Volume infusion produces abdominal distension, lung compression, and chest wall stiffening in pigs. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:575–82. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.2.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Daugherty EL, Hongyan Liang, Taichman D, Hansen-Flaschen J, Fuchs BD. Abdominal compartment syndrome is common in medical intensive care unit patients receiving large-volume resuscitation. J Intensive Care Med. 2007;22:294–9. doi: 10.1177/0885066607305247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Balogh Z, McKinley BA, Holcomb JB, Miller CC, Cocanour CS, Kozar RA, et al. Both primary and secondary abdominal compartment syndrome can be predicted early and are harbingers of multiple organ failure. J Trauma. 2003;54:848–59. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000070166.29649.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ivatury RR, Porter JM, Simon RJ, Islam S, John R, Stahl WM. Intra-abdominal hypertension after life-threatening penetrating abdominal trauma: prophylaxis, incidence, and clinical relevance to gastric mucosal pH. J Trauma. 1998;44:1016–21. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199806000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Balogh Z, Caldwell E, Heetveld M, D’Amours S, Schlaphoff G, Harris I, et al. Institutional practice guidelines on management of pelvic fracture-related hemodynamic instability: do they make a difference? J Trauma. 2005;58:778–82. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000158251.40760.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Horwood J, Akbar F, Maw A. Initial experience of laparostomy with immediate vacuum therapy in patients with severe peritonitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:681–7. doi: 10.1308/003588409X12486167520993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sugrue M, Buhkari ZY. Intra-Abdominal Pressure and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome in Acute General Surgery. World J Surg. 2009;33:1123–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Polat C, Arikan Y, Vatansev C, Akbulut G, Yilmaz S, Dilek FH, et al. The effect of increased intraabdominal pressure on colonic anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1314–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ivatury RR, Sugerman HJ. Abdominal compartment syndrome: a century later, isn’t it time to pay attention? Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2137–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200006000-00083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mayberry JC, Mullins RJ, Crass RA. Prevention of abdominal compartment syndrome by absorbable mesh prosthesis closure. Arch Surg. 1997;9:957–61. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430330023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hakkiluoto A, Hannukainen J. Open management with mesh and zipper of patients with intra-abdominal abscesses or diffuse peritonitis. Eur J Surg. 1992;158:403–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Akers DL, Fowl RJ, Kempczinski RF. Temporary closure of the abdominal wall by use of silicone rubber sheets after operative repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1991;14:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wild JM, Loundon MA. Modified Opsite sandwich for temporary abdominal closure: a non-traumatic experience. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:57–61. doi: 10.1308/003588407X155446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kirshtein B, Roy-Shapira A, Lantsberg L, Mizrahi S. Use of the “Bogotá bag” for temporary abdominal closure in patients with secondary peritonitis. A m J Surg. 2007;73:249–52. doi: 10.1177/000313480707300310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pliakos I, Papavramidis TS, Mihalopoulos N, Koulouris H, Kesisoglou I, Konstantinos Sapalidis, et al. Vacuum Assisted closure in severe abdominal sepsis with or without retention sutured sequential fascial closure: a clinical trial. Surgery. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.01.021. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mayberry JC, Burgess EA, Goldman RK. Enterocutaneous fistula and ventral hernia after absorbable mesh prosthesis closure for trauma: the plain truth. J Trauma. 2004;1:157–62. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000102411.69521.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nagy KK, Fildes JJ, Mahr C. Experience with three prosthetic materials in temporary abdominal wall closure. Am J Surg. 1996;5:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tekin S, Tekin A, Kucukkartallar T, Cakir M, Kartal A. Use of chorioamniotic membrane instead of Bogotá bag in open abdomen: How I Do It? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:815–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stone HH, Fabian TC, Turkleson ML, Jurkiewicz MJ. Management of acute full-thickness losses to the abdominal wall. Ann Surg. 1981;193:612–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198105000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Fry DE, Osler T. Abdominal wall considerations and complications in reoperative surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 1991;71:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)45329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Miller PR, Thompson JT, Faler BJ, Meredith JW, Chang MC. Late fascial closure in lieu of ventral hernia: the next step in open abdomen management. J Trauma. 2002;53:842–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Jernigan TW, Fabian TC, Croce MA, Moore N, Pritchard FE, Minard G, et al. Staged management of giant abdominal wall defects: acute and long-term results. Ann Surg. 2003;238:349–55. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000086544.42647.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Deligiannidis N, Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S, Gkoutzamanis G, Kessissoglou I, Papavasiliou I, et al. Two different prosthetic materials in the treatment of large abdominal wall defects. N Z Med J. 2008;121:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bee TK, Croce MA, Magnotti LJ, Zarzaur BL, Maish GO, 3rd, Minard G, et al. Temporary abdominal closure techniques: A prospective randomized trial comparing polyglactin 910 mesh and vacuum-assisted closure. J Trauma. 2008;65:337–42. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817fa451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cothren CC, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Moore JB, Burch JM. One hundred percent fascial approximation with sequential abdominal closure of the open abdomen. Am J Surg. 2006;192:238–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Reimer MW, Yelle JD, Reitsma B, Doumit G, Allen MA, Bell MS. Management of open abdominal wounds with a dynamic fascial closure system. Can J Surg. 2008;51:209–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tieu BH, Cho SD, Luem N, Riha G, Mayberry J, Schreiber MA. The use of the Wittmann Patch facilitates a high rate of fascial closure in severely injured trauma patients and critically ill emergency surgery patients. J Trauma. 2008;65:865–70. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31818481f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Poulakidas S, Kowal-Vern A. Component separation technique for abdominal wall reconstruction in burn patients with decompressive laparotomies. J Trauma. 2009;67:1435–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b5f346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kushimoto S, Miyauchi M, Yokota H, Kawai M. Damage control surgery and open abdominal management: recent advances and our approach. J Nippon Med Sch. 2009;76:280–90. doi: 10.1272/jnms.76.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Open Abdomen Advisory Panel. Management of the open abdomen: from initial operation to definitive closure. Am Surg. 2009;75:S1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cheatham ML, Safcsak K. Is the evolving management of intra abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome improving survival? Crit Care Med. 2010;38:402–7. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181b9e9b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]