UV light is lethal to most microorganisms owing to its relatively high energy and efficient absorption by biomacromolecules. However, bacterial endospores, which are responsible for a number of human diseases, such as anthrax and tetanus, are extremely resistant to UV radiation. For example, some Bacillus spores can be 100 times more resistant to UV light than the corresponding vegetative cells.[1] The highly unusual UV resistance is due to unique DNA photochemistry coupled with efficient damage repair in endospores.[2–8] Progress has been made in the elucidation of the damage-repair process.[6–9] However, although SP was discovered nearly half a century ago,[10] and despite the strong interest of the scientific community in how it is formed,[2,11] little is known about the mechanism of spore-DNA photochemistry.[12]

Thymine (T) is the most UV-sensitive nucleobase.[12] In typical cells after photochemical excitation, a T residue can dimerize with an adjacent T residue to generate cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and pyrimidine (6–4) photoproducts. In contrast, the dominant DNA photoproduct in endospores is a unique thymine dimer, 5-thyminyl-5,6-dihydrothymine, also called spore photoproduct or SP.[13] Spores express a specific enzyme, spore photoproduct lyase (SPL), which effectively reverses SP-dimer formation at the early germination phase and thus enables spores to resume their normal life cycle (Scheme 1).[2,13]

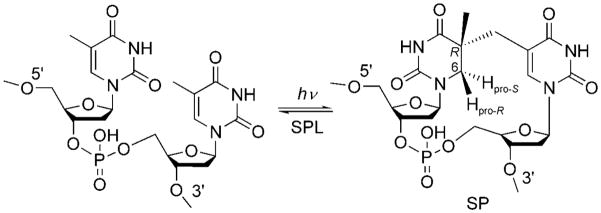

Scheme 1.

Formation of spore photoproduct upon the exposure of endospore DNA to UV radiation, and subsequent DNA repair by spore photoproduct lyase.

Although two mechanisms were proposed previously to explain SP formation, neither of them seemed to solve the problem unambiguously.[2,12] Varghese and Wang suggested that the SP was formed by a consecutive mechanism through recombination of a 5-α-thyminyl and a 5,6-dihydrothymin-5-yl radical;[14,15] however, how these two radicals were generated was unknown. By employing [D3]thymidine containing a CD3 moiety, Cadet and co-workers isolated the SP as a mixture of the 5S and 5R diastereomers after the photoreaction. More importantly, two thirds of the generated SP contained a deuterium atom on carbon atom C6. Although this finding appeared to suggest that a deuterium atom from the CD3 moiety migrated to the 6-position; such a conclusion was seriously undermined by the incomplete deuterium incorporation observed, which led Cadet and co-workers to conclude that the origin of the two C6 hydrogen atoms was unclear.[12] On the basis of these results, a concerted reaction mechanism involving the methyl group of one T residue and the C5–C6 double bond of the other T residue was proposed.[2,12]

Recently, the steric configuration of SP was determined by using the dinucleotide thymine dinucleoside monophosphate (TpT) instead of thymidine in a dry-film reaction.[11] The phosphate linker and the deoxyribose groups in TpT restrict the relative position of the Tresidues. Consequently, only one SP TpT species, formed through the addition of the CH3 group of the 3′-T residue to the C5 atom of the 5′-T residue, was observed by NMR spectroscopy, whereby the newly formed C5 stereocenter adopted an R configuration.[11] The SP TpT species generated in this manner exhibited identical properties to those of the compound obtained by the photo-irradiation of calf-thymus DNA, followed by enzyme digestion.[6] Furthermore, only the SP with the 5R configuration, and not the isomer (prepared by chemical synthesis) with the 5S configuration, is repaired by SPL.[16] All these results suggest that the 5R TpT SP is truly the biologically relevant species.

Now that the steric configuration of SP has been revealed, the photoreaction mechanism through which it is generated remains to be elucidated. In SP, the C6 atom of 5′-T is bonded to two hydrogen atoms and is prochiral. As the formation of this prochiral center constitutes a major structural change during the photoreaction, it should be possible to shed light on the mechanism by deciphering the origins of these hydrogen atoms. Although we were puzzled by the observation of only 60% deuterium incorporation in the study by Cadet and co-workers, we felt that it was a reasonable assumption that one H atom is retained from the original 5′-T residue, whereas the other is derived from the methyl group of 3′-T during the photochemical formation of SP. To test this hypothesis, we prepared two deuterium-labeled TpT dinucleotides and monitored the hydrogen-/deuterium-atom transfer after UV irradiation by 1H NMR spectroscopy (500 MHz). The results showed that a hydrogen atom from the methyl group of 3′-T is transferred intramolecularly to the C6 atom of 5′-T in SP in a highly diastereoselective manner. This result, together with the previous assignment of the configuration C5 in SP,[11] now enables us to propose a detailed mechanism for the SP photoreaction.

We started our investigation with a selectively labeled [D3]TpT dinucleotide containing a [D3]methyl group in the 3′-Tresidue (Scheme 2a).[17] [D3]TpT was dissolved in methanol and transferred to a 10 cm petri dish; solvent evaporation yielded a good thin film.[18] UV irradiation of the film for 45 min produced the labeled SP in approximately 0.1% yield.[19] After multiple reactions and HPLC separation, 5 mg of the labeled SP TpT product was obtained from 3.5 g of [D3]TpT. For structural comparison, nonlabeled SP TpT was also prepared by organic synthesis.[20]

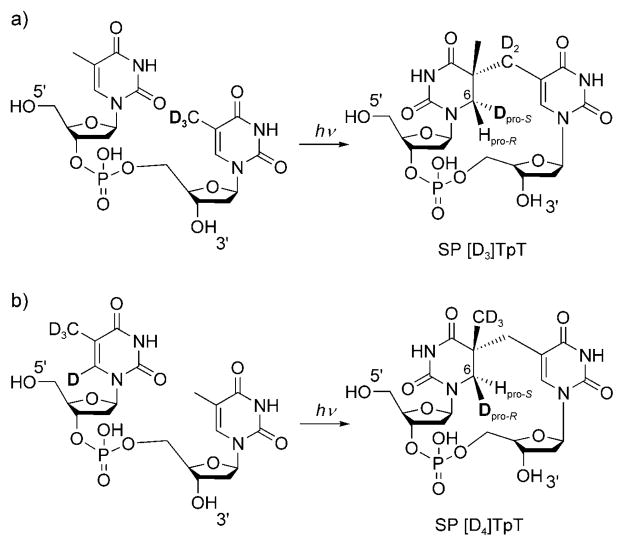

Scheme 2.

UV irradiation of the isotope-labeled thymine dinucleotides a) [D3]TpT and b) [D4]TpT to give the corresponding SP derivatives.

The ESI mass spectrum of the labeled SP TpT species exhibited an [M+H]+ signal at m/z 550.2,[17] which suggested that all three deuterium atoms in [D3]TpT were retained after the photoreaction. Interestingly, a singlet signal at δ=3.01 ppm was observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of the obtained SP [D3]TpT (Figure 1b). In contrast, the synthesized SP TpT exhibited two doublets at δ =3.15 and 3.02 ppm (Figure 1b), which were assigned to the 5′-T 6-Hpro-S and 6-Hpro-R hydrogen atoms, respectively.[11] It thus appears that during the photoreaction, a methyl deuterium atom is transferred to the 5′-T 6-Hpro-S position, whereas the hydrogen atom from the original 5′-T residue remains at 6-Hpro-R (Scheme 2a). The lack of 2JH, H coupling at C6 in 5′-T as a result of the replacement of a hydrogen atom by a deuterium atom changes the NMR signal from two doublets in SP TpT to a singlet in SP [D3]TpT.

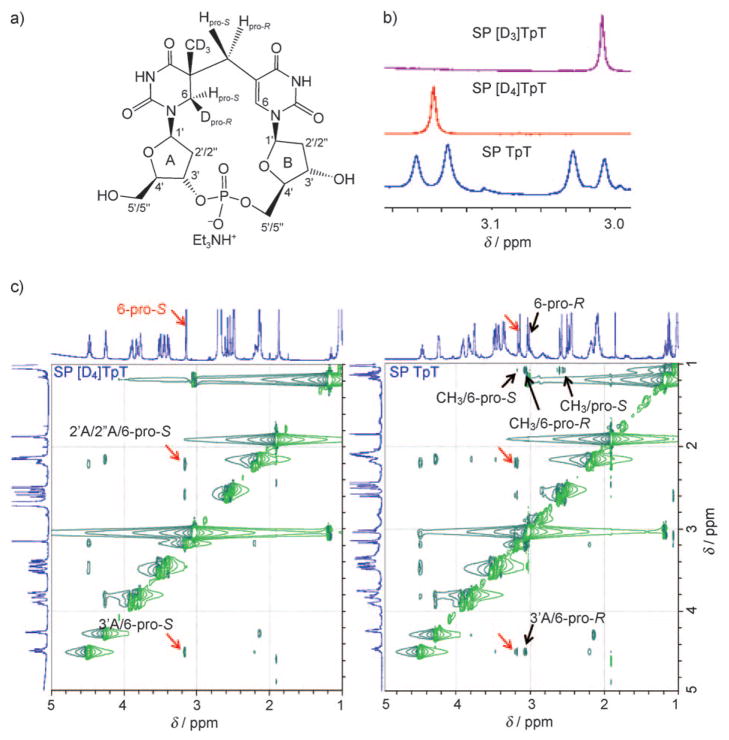

Figure 1.

a) Structure of isolated SP [D4]TpT. b) Zoom-in view of the 1H NMR signals for the 5′-T 6-Hpro-S and 6-Hpro-R hydrogen atoms in SP [D3]TpT, SP [D4]TpT, and SP TpT. c) Zoom-in view of the ROESY spectra of SP TpT and SP [D4]TpT dissolved in [D6]dimethyl sulfoxide. The signals associated with 6-Hpro-S are indicated by red arrows; these signals are observed for both SP species. The signals associated with 6-Hpro-R or CH3 are indicated by black arrows; these signals are not present in the spectrum for SP [D4]TpT as a result of the deuterium substitution. The interaction between the 5′-T 6-Hpro-S and 3′-T 6-H atoms yields a ROESY signal at δ=3.14–7.51 ppm, which is outside the range of the zoom-in view. The full 1D and 2D NMR spectra for these SP species can be found in the Supporting Information.

To further validate the observed hydrogen-atom transfer, we also prepared a [D4]TpT dinucleotide with all four carbon-bonded hydrogen atoms in 5′-T replaced with deuterium atoms (Scheme 2b).[17] In this compound, we incorporated a deuterium atom at C6 in 5′-T to distinguish the original hydrogen atom at this position from the transferred hydrogen atom after the photoreaction. The photoreaction was carried out by using a [D4]TpT thin film prepared by a similar procedure to that described above. However, the SP was formed much faster than for the [D3]TpT system. The increased reaction rate is probably due to the lack of a primary kinetic isotope effect (KIE) after the replacement of CD3 with CH3 in 3′-T. UV irradiation of [D4]TpT for 45 min afforded the corresponding SP in approximately 0.4% yield. After multiple reactions and HPLC separation, 18 mg of the labeled photoproduct was isolated from 1.6 g of [D4]TpT. ESIMS analysis revealed that the isolated SP TpT product had again retained all deuterium atoms. Furthermore, the photoproduct exhibited a singlet signal at δ =3.14 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum (Figure 1b), wich suggested that a methyl hydrogen atom had been transferred to the 5′-T 6-Hpro-S position in the formed SP [D4]TpT (Scheme 2b).

To completely exclude the possibility that the transferred hydrogen atom comes from trace methanol left in the dry film, we prepared the film with [D4]methanol and irradiated the film with UV light. The resulting SP TpT had an [M+H]+ signal at m/z 551.2,[17] which corresponds to the formation of SP [D4]TpT. This observation confirms that the transferred hydrogen atom is from the 3′-T CH3 moiety, and not from the trace solvent in the film.

To further verify the observation that a hydrogen atom is transferred to the 5′-T 6-Hpro-S position in the photoreaction, we determined the hydrogen-atom correlations through space in ROESY experiments for both SP TpT and SP [D4]TpT. In SP TpT, the 6-Hpro-R atom mainly interacts with 3′A-H and the CH3 moiety, whereas 6-Hpro-S associates with 2′A-H/2″A-H, 3′A-H, and 6-H in 3′-T.[11] In contrast, for SP [D4]TpT, the NMR signals associated with 5′-T 6-Hpro-R and/or CH3 disappear as a result of deuterium substitution, whereas the signals associated with 6-Hpro-S remain (Figure 1c). These observations agree with our 1D NMR spectroscopic results and establish that a hydrogen atom from the methyl group of 3′-T is transferred to the 5′-T 6-Hpro-S position in the photo-reaction.

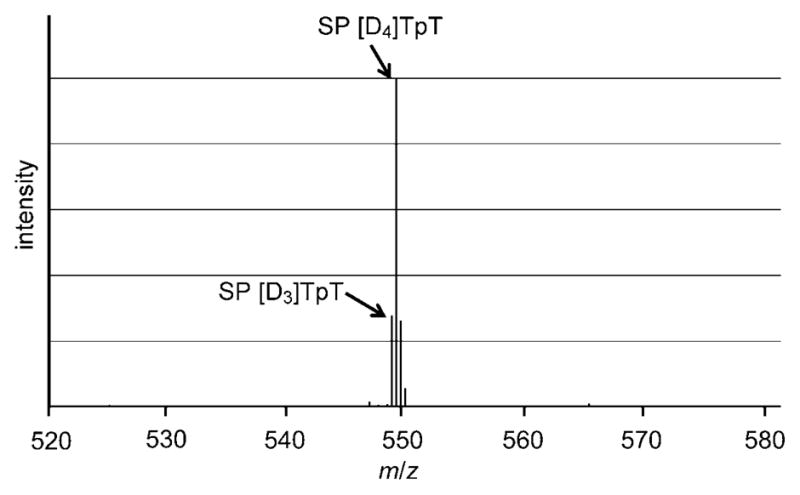

The faster photoreaction when [D4]TpT was employed suggested the likely existence of a primary kinetic isotope effect (KIE). To determine the KIE, we prepared a film by using equal amounts of [D3]TpT and [D4]TpT, carried out the photoreaction, and isolated the SP TpT photoproduct by HPLC. ESIMS analysis of the obtained SP TpT products revealed the presence of both D3- and D4-labeled SP TpT species. The signal intensity of the D4 species was 3.5 ± 0.3 times as strong as that of the D3-labeled SP in both positive and negative ion modes (Figure 2).[17] This result suggests a primary KIE of 3.5 for the photochemical SP formation.

Figure 2.

ESIMS spectrum of the isolated SP [D3]TpT and SP [D4]TpT complexes in the negative ionization mode. The ESIMS spectrum recorded in the positive mode can be found in the Supporting Information. The [M−H]− signal at m/z 548.1 corresponds to the SP [D3]TpT species. The [M−H]− signal at m/z 549.2 corresponds to a combination of SP [D4]TpT and the first isotopic peak of SP [D3]TpT, which is predicted to be 22.4% of the signal intensity of the SP [D3]TpT species. Subtraction of the isotopic contribution of SP [D3]TpT from the signal strength of the peak at m/z 549.2 resulted in the contribution of SP [D4]TpT to the signal intensity. Comparison of this number with the intensity of the peak at m/z 548.1 yielded the primary isotope effect of 3.5.

To test whether the detected MS-signal intensities truly reflected the yields of the SP products, we mixed authentic samples of SP [D3]TpT and SP [D4]TpT in a 1:3.5 ratio and injected the mixture into the ESI mass spectrometer. As expected, the D4 species exhibited a MS signal that was about 3.5 times as strong as that of the D3 species. This observation excludes the influence of the ionization and ion-detection processes in the determination of the KIE and demonstrates that the MS signal ratio truly represents the kinetic isotope effect.

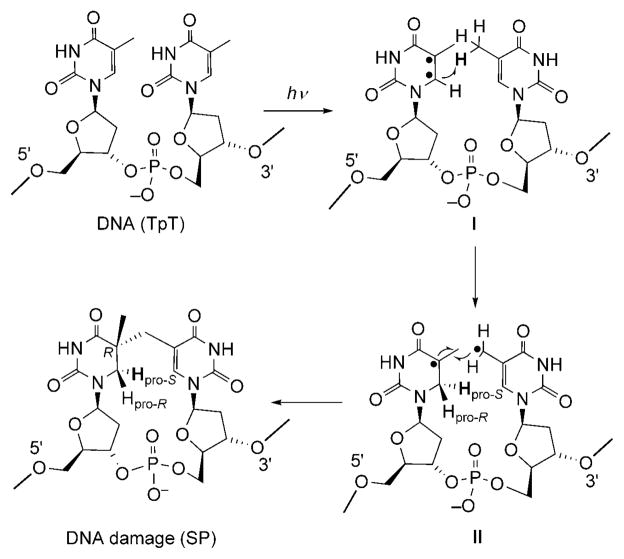

These results provide mechanistic insight into the photochemical formation of SP. Thus, in agreement with our observations, UV light first excites the C=C bond of 5′-T to form a pair of radicals (intermediate I; Scheme 3). Abstraction of a hydrogen atom from the 3′-T methyl group by the C6 radical then leads to the formation of a 5-α-thyminyl and a 5,6-dihydrothymin-5-yl radical (intermediate II). This step is potentially rate-limiting, as indicated by the observed primary isotope effect of 3.5 after deuterium substitution at the 3′-T methyl group. The resulting two radicals subsequently recombine to yield the final product SP.

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanism for the formation of SP.

This mechanism accounts for the observed steric configuration of the SP molecule. It has been suggested that, to form SP, the DNA in spores adopts an A-like conformation,[21] whereby thymine adopts an anti configuration relative to the deoxyribose moiety.[2,12] This proximity dictates that the H atom from the 3′-T CH3 group can only be transferred to the 6-Hpro-S position. Owing to the ultrafast nature of the photoreaction,[22] the two radicals in intermediate II have no time to change their relative positions, and 5R remains the sole configuration after they recombine to form SP.

Although organic radicals are known to undergo H-atom-abstraction reactions, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first time that the C5–C6 double bond has been observed to participate in such a reaction in thymine photochemistry. We tentatively propose that the relative position of the Tresidues in the dry film or A-form spore DNA facilitates this novel photochemistry, as it was suggested recently that during thymine photodimerization, the static TT conformation and not the conformational motion at the instant of excitation governs the outcome of the photoreaction.[22] Although our data appear to support the consecutive mechanism proposed in Scheme 3, the concerted mechanism suggested by Cadet and co-workers cannot be ruled out at this point.

The proposed biradical intermediates I and II have not been observed directly in SP formation; however, their existence is well-documented in photochemical studies of DNA: Species I is responsible for the formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs), and it has been suggested that SP and CPD share a similar triplet excited state.[3] The radicals in intermediate II have been generated by UV irradiation and observed by EPR spectroscopy.[23–25] Further studies to trap and characterize these radical intermediates in SP formation in an attempt to confirm the proposed consecutive mechanism are in progress.

Footnotes

We thank Prof. Eric Long at IUPUI for helpful discussions, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R00ES017177) as well as the IUPUI startup fund for financial support. The NMR and MS facilities are supported by National Science Foundation MRI grants CHE-0619254 and DBI-0821661, respectively.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201005228.

References

- 1.Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:548. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desnous CL, Guillaume D, Clivio P. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1213. doi: 10.1021/cr0781972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Douki T, Setlow B, Setlow P. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2005;4:591. doi: 10.1039/b503771a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douki T, Setlow B, Setlow P. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:163. doi: 10.1562/2004-08-18-RA-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rebeil R, Nicholson WL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161278998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandor A, Berteau O, Douki T, Gasparutto D, Sanakis Y, Ollagnier-de-Choudens S, Atta M, Fontecave M. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602297200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buis J, Cheek J, Kalliri E, Broderick J. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pieck J, Hennecke U, Pierik A, Friedel M, Carell T. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandor-Proust A, Berteau O, Douki T, Gasparutto D, Ollagnier-de-Choudens S, Fontecave M, Atta M. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:36361. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806503200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donnellan JE, Jr, Setlow RB. Science. 1965;149:308. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3681.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantel C, Chandor A, Gasparutto D, Douki T, Atta M, Fontecave M, Bayle PA, Mouesca JM, Bardet M. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16978. doi: 10.1021/ja805032r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cadet J, Vigny P. The Photochemistry of Nucleic Acids. In: Morrison H, editor. Bioorganic Photochemistry: Photochemistry and the Nucleic Acids. Vol. 1. Wiley; New York: 1990. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Setlow P. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2001;38:97. doi: 10.1002/em.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang SY. Photochemistry and photobiology of nucleic acids. Vol. 1. Academic Press; New York: 1976. p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varghese AJ. Biochemistry. 1970;9:4781. doi: 10.1021/bi00826a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandra T, Silver SC, Zilinskas E, Shepard EM, Broderick WE, Broderick JB. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2420. doi: 10.1021/ja807375c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.See the Supporting Information.

- 18.Varghese AJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;38:484. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90739-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.This yield is in line with the previously reported yields in reference [11]. The reason for this seemingly low yield is that only thymine residues in the “right” conformation at the instant of excitation dimerize, and the vast majority of excited molecules are thermally quenched.[11] The dry film further restricts the thermal motion of TpT and its ability to undergo conformational changes; thus, only a very small portion of TpT can form SP TpT. Unreacted TpT (80–90%) was recovered after HPLC separation and reused for the SP photoreaction.

- 20.Kim SJ, Lester C, Begley TP. J Org Chem. 1995;60:6256. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee KS, Bumbaca D, Kosman J, Setlow P, Jedrzejas MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708244105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreier WJ, Schrader TE, Koller FO, Gilch P, Crespo-Hernández CE, Swaminathan VN, Carell T, Zinth W, Kohler B. Science. 2007;315:625. doi: 10.1126/science.1135428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pershan PS, Shulman RG, Wyluda BJ, Eisinger J. Science. 1965;148:378. doi: 10.1126/science.148.3668.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alcántara R, Wang SY. Photochem Photobiol. 1965;4:473. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisinger J, Shulman RG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1963;50:694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.50.4.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]