Abstract

The fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe is a model organism used widely to study various aspects of eukaryotic biology. A collection of heterozygous diploid strains containing individual deletions in nearly all S. pombe genes has been created using a pCr based strategy. However, deletion of some genes has not been possible using this methodology. Here we use an efficient knockout strategy based on plasmids that contain large regions homologous to the target gene to delete an additional 29 genes. The collection of deletion mutants now covers 99% of the fission yeast open reading frames.

Keywords: fission yeast, gene deletion, genomics, essential genes, vectors

Introduction

Although forward genetic screens have provided many important insights into various aspects of cell biology, they are limited by the large numbers of mutants that must be analyzed and inherent biases in mutagenesis techniques. Systematic reverse genetic screens using genome-wide gene deletion collections or RNAi libraries provide a powerful alternative to forward genetic screens (reviewed in refs. 1-5). Studies with the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae have shown the usefulness of such gene deletion collection for numerous studies including drug discovery (reviewed in refs. 6-9). The fission yeast S. pombe is an important model organism sharing many features with cells of higher eukaryotes. The availability of the S. pombe genome sequence10 and PCR-based gene deletion technology11 allowed researchers involved in the S. pombe genome deletion project (KRIBB-Bioneer-CRUK consortium) to generate a set of 4.836 heterozygous diploid deletion mutants covering 98.4% of the fission yeast open reading frames (Kim et al. in press). However, for some genes a deletion could either not be constructed or the analysis of mutant phenotypes gave ambiguous results. Here we use an efficient knock-out strategy to delete 29 of these genes.

Results

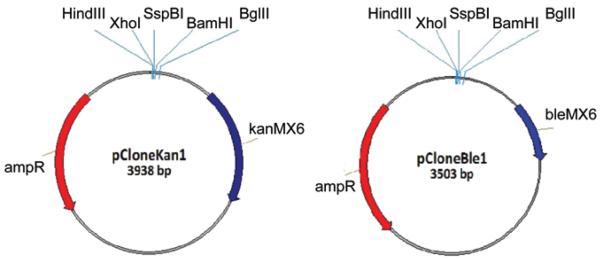

We speculated that some of the genes which could not be deleted by the KRIBB-Bioneer-CRUK consortium may require longer regions of homology for efficient gene targeting12,13 and may be amenable to knockout by our recently developed technique.14 This protocol is based on knockout constructs that contain large regions homologous to the target gene cloned into vectors. The cloning vectors pCloneNat1 and pCloneHyg1 contain dominant drug resistance markers conferring resistance to nourseothricin (clonat) and hygromycin B, respectively.15 Here we introduce two new cloning vectors pCloneKan1 and pCloneBle1 which contain dominant drug resistance markers conferring resistance to geneticin and phleomycin, respectively (Fig. 1). Both pCloneKan1 and pCloneBle1 are compatible with our knockout protocol as described in Gregan et al.15 and http://mendel.imp.ac.at/Pombe_deletion.

Figure 1.

Maps of cloning vectors pCloneKan1 and pCloneBle1. Restriction sites used for cloning of the homology regions are indicated. Nucleotide sequence of pCloneKan1 (GQ354684) and pCloneBle1 (GQ354685) can be found in GenBank.

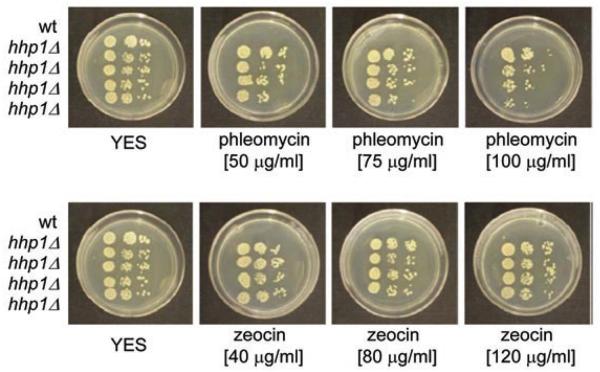

To demonstrate the usefulness of the pCloneBle1 vector, we used it to create knockout construct for deletion of the hhp1 gene encoding the casein kinase 1.16 After transformation of a linearized pCloneBle1-hhp1 plasmid into fission yeast we were able to recover phleomycin-resistant colonies. Colony PCR showed that we had successfully deleted the hhp1 gene in 7 out of 10 phleomycin-resistant transformants. The pCloneBle1 vector conferred resistance to both phleomycin and zeocin, which is a commercially produced antibiotic containing phleomycin (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

pCloneBle1 confers resistance to phleomycin and zeocin. To test the usefulness of the pCloneBle1, we used this plasmid to delete hhp1 gene. We first constructed hhp1 deletion plasmid (pCloneBle1-hhp1) according to protocol described in Gregan et al.15 After linearization of the pCloneBle1-hhp1 plasmid with the restriction enzyme XbaI, we transformed it into a wild-type S. pombe strain and selected for phleomycin-resistant colonies. Colony-pCr showed that we successfully deleted hhp1 in 7 out of 10 tested colonies. Transformants were resistant to both phleomycin and zeocin, which is a commercially produced antibiotic containing phleomycin. A 10-fold dilution series of wild-type (wt) (JG11318) and four transformants where hhp1 has been deleted with pCloneBle1-hhp1 construct (JG15352) were spotted onto YeS plates containing the indicated concentrations [mg/ml] of either phleomycin or zeocin. Plates were incubated at 32°C for 3 days.

We used the pCloneKan1 to create knockout constructs of 64 genes for which deletion could either not be constructed, the analysis of mutant phenotypes gave ambiguous results such as abnormal segregation of the selection marker after tetrad analysis or the phenotype was different from published data (Kwang-Lae Hoe, unpublished data). These constructs contained regions of homology, which were larger than those used by the KRIBB-Bioneer-CRUK consortium (350–800 bp compared to 80–350 bp) (Kim et al. in press). We found that indeed, after transformation of knockout plasmids into a diploid S. pombe strain we were able to create heterozygous knockout mutants for 49 genes. Out of the 49 deleted genes, 29 strains were missing from the S. pombe genome deletion collection and the remaining 21 strains were used to confirm ambiguous data (Kwang-Lae Hoe, unpublished data). To identify genes essential for vegetative growth, we sporulated the heterozygous diploid strains and dissected asci on rich medium. 13 of the 49 genes analyzed were essential for vegetative growth (Table 1, Fig. S1). Five of these 13 essential genes have been previously described.17-21

Table 1.

Deletion phenotype

| Deleted gene | Mutant phenotype |

Deleted gene | Mutant phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPAC1250.07* | essential | SPAC15E1.03* | viable |

| SPAC23C4.04c* | viable | SPCC1682.05c* | essential |

| SPAC27E2.12* | viable | SPBC119.10* | viable |

| SPAC56F8.07* | essential | SPAC4D7.08c* | viable |

| SPAPB1A10.16* | viable | SPAC1786.02 | viable |

| SPCC1393.14* | viable | ||

| SPAC1F3.04c* | viable | SPAC30D11.09 | viable |

| SPAC23D3.14c* | viable | SPAC3A11.05c | viable |

| SPAC2F7.16c* | viable | SPBC543.04 | essential |

| SPAC9.09* | viable | SPCC191.02c | viable |

| SPAPB15E9.01c* | viable | SPAC1952.13 | essential |

| SPAPB18E9.02c* | viable | SPAC1B1.03c | essential |

| SPBC16G5.19* | viable | SPAC1F7.04 | essential |

| SPBC17G9.06c* | viable | SPAC2C4.11c | essential |

| SPBC215.15* | viable | SPAC3H8.10 | viable |

| SPBC21D10.06c* | viable | SPAC56F8.10 | essential |

| SPBC23G7.09* | viable | SPAPB1E7.02c | viable |

| SPBC365.05c* | essential | SPBC146.13c | viable |

| SPBC685.08* | viable | SPBC16C6.09 | viable |

| SPBC6B1.12c* | viable | SPBC428.19c | essential |

| SPBC800.14c* | viable | SPCC18.04 | essential |

| SPBP23A10.11c* | viable | SPCC645.05c | essential |

| SPBPB8B6.03* | viable | SPAC589.12 | viable |

| SPBPB8B6.06c* | viable | SPBC1778.01c | viable |

| SPCC290.04* | viable | SPBC32F12.01c | viable |

genes which were missing from the S. pombe genome deletion collection.

We next tried to find common characteristics that could explain why these genes were difficult to delete. However, gene ontology (GO) analysis of the deleted genes showed no enrichment for any particular GO category. The genes were randomly distributed along all three S. pombe chromosomes and showed a similar percentage of essential genes (26%) to that calculated from the analysis of 4.836 S. pombe genes (26.1%) (Kim et al. in press). We conclude that for these genes the length of homology for recombination during construction of the deletion is likely to be important.

Discussion

In summary, we describe two new plasmids for gene deletions in the fission yeast S. pombe. The plasmids pCloneKan1 and pCloneBle1 can be used for single gene deletions, but they are particularly suitable for high-throughput knockout screens and for deletion of genes which require large regions of homology. Both pCloneKan1 and pCloneBle1 are compatible with the knockout protocol described in Gregan et al.14,15 Detailed instructions how to use these plasmids to prepare knockout constructs for all predicted fission yeast genes is available in a form of searchable database http://mendel.imp.ac.at/Pombe_deletion. The added advantage of this strategy is that a library of knockout plasmids is created which can be used to knockout genes in strains with various genetic backgrounds. Importantly, we used the pCloneKan1 plasmid to make 29 deletion strains, which were missing from the S. pombe genome deletion collection (Kim et al. in press). Together with the previously constructed 4.836 heterozygous deletions, this covers 99% of the fission yeast open reading frames. Given the fact that fission yeast is an important model organism, we expect that this genome-wide deletion collection will become an important tool for studying molecular aspects of eukaryotic biology and will accelerate the use of S. pombe for various comparative studies of eukaryotic cell processes.

Materials and Methods

S. pombe media and growth conditions were as described in.22,23 G418 (Gibco), Zeocin (InvivoGen) and Phleomycin (Sigma) solutions were added to media after autoclaving.

To create plasmid pCloneKan1, we first mutated HindIII restriction site in kanMX6 gene of the plasmid pFA6aKanMX6 using site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and the following mutagenic oligonucleotides: TCT GGA AAG AAA TGC ATA AAC TTT TGC CAT TCT CAC CGG and CCG GTG AGA ATG GCA AAA GTT TAT GCA TTT CTT TCC AGA. Then we replaced the EcoRI/PstI fragment of the pCloneNat1 plasmid containing natMX4 by the EcoRI/PstI fragment of the mutated plasmid pFA6aKanMX6.

To create plasmid pCloneBle1, we replaced the BglII/SpeI fragment of the pCloneNat1 plasmid containing natMX4 by the BglII/SpeI fragment of the plasmid pFA6BleMX6 containing bleMX6 conferring resistance to phleomycin.24,25

To create plasmid pCloneBle1-hhp1, we cut out hhp1 homology regions from the plasmid pCloneNat1-hhp1,26 using restriction enzymes HindIII and BamHI and inserted into HindIII/ BamHI sites of the plasmid pCloneBle1.

All the pCloneKan1 and pCloneBle1 deletion constructs used in this study were made according to protocol described in Gregan et al.15 and http://mendel.imp.ac.at/Pombe_deletion. In addition, dwin and upin oligonucleotides used for constructing pCloneKan1 deletion constructs contained tag sequences (barcodes) of 20 bp unique to each deletion mutant (Table S1). Large numbers of deletion strains can be pooled and analyzed in parallel in competitive growth assays. The barcodes allow identification of individual mutants in the pool of mutants.1 The ability to assess deletion strains in parallel will significantly decrease the amount of labor and materials needed for fitness screens.

The pCloneKan1 deletion constructs were transformed into S. pombe strain SP286 (ade6-M210/ade6-M216, leu1-32/leu1-32, ura4-D18/ura4-D18 h+/h+) using a lithium acetate method. Transformants were selected on YES agar plates containing 100 mg/ml G418.

Essentiality was determined by a microscopic observation of colony-forming ability of spores on YES (rich medium) at 32°C. The spores were derived from corresponding heterozygous diploid deletion strains transformed with the pON177 plasmid containing the mat1-M sequence (a gift from O. Nielson).

Gene Ontology analysis was performed according to http://go.princeton.edu/cgi-bin/GOTermFinder.27

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Austrian Science Fund grants P18955, P20444 and F3403. M.B. thanks for the short-term FEMS fellowship (FRF 2009-1).

Footnotes

Note

Supplementary materials can be found at: www.landesbioscience.com/supplement/SpirekCC9-12-Sup.pdf

References

- 1.Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–6. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su KC, Barinova Y, Fellner M, et al. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;448:151–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillenmeyer ME, Fung E, Wildenhain J, Pierce SE, Hoon S, Lee W, et al. The chemical genomic portrait of yeast: uncovering a phenotype for all genes. Science. 2008;320:362–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1150021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giaever G, Chu AM, Ni L, Connelly C, Riles L, Veronneau S, et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002;418:387–91. doi: 10.1038/nature00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giaever G, Shoemaker DD, Jones TW, Liang H, Winzeler EA, Astromoff A, et al. Genomic profiling of drug sensitivities via induced haploinsufficiency. Nat Genet. 1999;21:278–83. doi: 10.1038/6791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins SR, Miller KM, Maas NL, Roguev A, Fillingham J, Chu CS, et al. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature. 2007;446:806–10. doi: 10.1038/nature05649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melese T, Hieter P. From genetics and genomics to drug discovery: yeast rises to the challenge. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:544–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castrillo JI, Oliver SG. Yeast as a touchstone in post-genomic research: strategies for integrative analysis in functional genomics. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;37:93–106. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2004.37.1.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinmetz LM, Davis RW. Maximizing the potential of functional genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:190–201. doi: 10.1038/nrg1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood V, Gwilliam R, Rajandream MA, Lyne M, Lyne R, Stewart A, et al. The genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature. 2002;415:871–80. doi: 10.1038/nature724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahler J, Wu JQ, Longtine MS, Shah NG, McKenzie A, 3rd, Steever AB, et al. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krawchuk MD, Wahls WP. High-efficiency gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe using a modular, PCR-based approach with long tracts of flanking homology. Yeast. 1999;15:1419–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19990930)15:13<1419::AID-YEA466>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decottignies A, Sanchez-Perez I, Nurse P. Schizosaccharomyces pombe essential genes: a pilot study. Genome Res. 2003;13:399–406. doi: 10.1101/gr.636103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregan J, Rabitsch PK, Sakem B, Csutak O, Latypov V, Lehmann E, et al. Novel genes required for meiotic chromosome segregation are identified by a high-throughput knockout screen in fission yeast. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1663–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregan J, Rabitsch PK, Rumpf C, Novatchkova M, Schleiffer A, Nasmyth K. High-throughput knockout screen in fission yeast. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2457–64. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhillon N, Hoekstra MF. Characterization of two protein kinases from Schizosaccharomyces pombe involved in the regulation of DNA repair. EMBO J. 1994;13:2777–88. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermand D, Bamps S, Tafforeau L, Vandenhaute J, Makela TP. Skp1 and the F-box protein Pof6 are essential for cell separation in fission yeast. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9671–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211358200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.May KM, Watts FZ, Jones N, Hyams JS. Type II myosin involved in cytokinesis in the fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1997;38:385–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1997)38:4<385::AID-CM8>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arellano M, Duran A, Perez P. Localisation of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe rho1p GTPase and its involvement in the organisation of the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2547–55. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.20.2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen XQ, Du X, Liu J, Balasubramanian MK, Balasundaram D. Identification of genes encoding putative nucleoporins and transport factors in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe: a deletion analysis. Yeast. 2004;21:495–509. doi: 10.1002/yea.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tange Y, Hirata A, Niwa O. An evolutionarily conserved fission yeast protein, Ned1, implicated in normal nuclear morphology and chromosome stability, interacts with Dis3, Pim1/RCC1 and an essential nucleoporin. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4375–85. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabitsch KP, Petronczki M, Javerzat JP, Genier S, Chwalla B, Schleiffer A, et al. Kinetochore recruitment of two nucleolar proteins is required for homolog segregation in meiosis I. Dev Cell. 2003;4:535–48. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Driessche B, Tafforeau L, Hentges P, Carr AM, Vandenhaute J. Additional vectors for PCR-based gene tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe using nourseothricin resistance. Yeast. 2005;22:1061–8. doi: 10.1002/yea.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hentges P, Van Driessche B, Tafforeau L, Vandenhaute J, Carr AM. Three novel antibiotic marker cassettes for gene disruption and marker switching in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 2005;22:1013–9. doi: 10.1002/yea.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gregan J, Zhang C, Rumpf C, Cipak L, Li Z, Uluocak P, et al. Construction of conditional analog-sensitive kinase alleles in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2996–3000. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyle EI, Weng S, Gollub J, Jin H, Botstein D, Cherry JM, et al. GO::TermFinder—open source software for accessing Gene Ontology information and finding significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3710–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.