Abstract

Targeted therapies for cancer are inherently limited by the inevitable recurrence of resistant disease after initial responses. To define early molecular changes within residual tumor cells that persist after treatment, we analyzed drug sensitive lung adenocarcinoma cell lines exposed to reversible or irreversible EGFR inhibitors, alone or in combination with MET kinase inhibitors, to characterize the adaptive response that engenders drug resistance. Tumor cells displaying early resistance exhibited dependence on MET-independent activation of BCL-2/BCL-XL survival signaling. Further, such cells displayed a quiescence-like state associated with greatly retarded cell proliferation and cytoskeletal functions that were readily reversed after withdrawal of targeted inhibitors. Findings were validated in a xenograft model, demonstrating BCL-2 induction and p-STAT3[Y705] activation within the residual tumor cells surviving the initial anti-tumor response to targeted therapies. Disrupting the mitochondrial BCL-2/BCL-XL antiapoptotic machinery in early survivor cells using BH3 mimetic agents such as ABT-737, or by dual RNAi-mediated knockdown of BCL-2/BCL-XL, was sufficient to eradicate the early resistant lung tumor cells evading targeted inhibitors. Similarly, in a xenograft model the preemptive co-treatment of lung tumor cells with an EGFR inhibitor and a BH3 mimetic eradicated early TKI-resistant evaders and ultimately achieved a more durable response with prolonged remission. Our findings prompt prospective clinical investigations using BH3-mimetics combined with targeted receptor kinase inhibitors to optimize and improve clinical outcomes in lung cancer treatment.

Keywords: EGFR, MET, inhibitor, resistance, lung cancer, STAT3, BCL-2, BCL-XL, BH3-mimetic, ABT-737

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer and continues to have the highest cancer-mortality rates. Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) is a main class of druggable molecular targets, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)(1, 2), MET (3, 4), that can be therapeutically inhibited in human cancer therapy. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), gefitinib and erlotinib, are approved targeted agents against non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with enhanced efficacy towards tumors that express somatic sensitizing kinase domain mutations (e.g. L858R, exon 19 deletions)(5–7). One of the most formidable challenges of targeted therapy is the invariable tumor secondary resistance after initial response. MET genomic amplification has been implicated in about 20% of acquired EGFR resistance (8, 9) while the EGFR gatekeeper T790M kinase mutation (10–12) accounts for approximately half of the resistant cases. Further targeting strategies to overcome EGFR resistance include the use of irreversible TKIs (10, 13, 14), pan-EGFR/ERBB kinase inhibitors (15), and MET inhibitors (8, 16). The MET receptor has been shown to be an important molecule in a variety of malignancies (3, 17) and has recently been validated as an attractive therapeutic target in cancer therapy, including lung cancer (4, 18–23). Reversible small molecule inhibitors to target against MET have been developed for novel anti-cancer therapeutic intervention (20, 21, 24–26). Studies from our group and others have recently demonstrated the cross-talk signaling network between EGFR and MET, and also the role of MET inhibition in combination with EGFR inhibitor in lung cancer in overcoming MET amplified resistance (8) or T790M-EGFR mediated resistance (16) to EGFR-TKI.

Further knowledge into additional mechanisms of tumor cell resistance to targeted inhibitors should prove to be of great significance in the quest for novel effective treatment strategies to impact the long-term prognosis of lung cancer. Majority of the reported studies investigating mechanisms of tumor resistance centered on late time window after chronic exposure to TKIs at escalating dosing concentrations when secondary resistant clones ultimately arose and propagated from the parental drug-sensitive cell populations. Nonetheless, a deep understanding of the entire spectrum of tumor cells mechanistic strategies to escape or evade targeted therapeutics in resistance, especially during the early inhibitory phase, remains to be better defined at present (27, 28). Here, we investigated the “early” molecular events in lung tumor cells under targeted EGFR alone or combined with MET kinase inhibitors treatment. Our results identified that a resurgence of prosurvival-antiapoptotic signaling was evident in the surviving tumor with early evasion against the targeted kinase inhibitors, that involved a TKI-induced dependence of activated STAT3, and its transcriptional target BCL-2/BCL-XL, with therapeutic translational values. Our results showed that proapoptotic BCL-2 Homology Domain 3 (BH3)-mimetic, such as ABT-737, can be effective in eradicating these “early” TKI-resistant lung tumor evader cells, thereby potentially enhancing the long-term efficacy of targeted EGFR lung cancer therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Immunoblotting

Lung cancer cell lines were obtained directly from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown under standard cell culture conditions. Cell lines characterization and authentication were performed by the ATCC Molecular Authentication Center, using COI for interspecies identification and STR anlaysis (DNA fingerprinting) for intraspecies identification. SDS-PAGE and Western blotting were performed as previously described (16, 29). The primary antibodies used are as follows: phospho-MET[Y1234/1235](Cell Signaling Technology, CST), MET (C-12, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), phospho-EGFR[Y1068] (CST), EGFR (Santa Cruz), phosphotyrosine (p-Tyr), phospho-AKT[S473], AKT, phospho-MAPK(ERK1/2)[T202/Y204](all from CST), MAPK(ERK1/2)(Biosource), phospho-STAT3[Y705] (CST), STAT3, BCL-2, BCL-XL (all from Zymed), cleaved-Caspase-3[Asp175], cleaved-PARP[Asp214], phospho-STAT5[Y694](all from CST), survivin (Zymed) and actin (Santa Cruz).

Chemicals and Inhibitors

EGFR inhibitor(reversible) erlotinib was prepared as previously described (29, 30). MET inhibitors SU11274, PHA665752 and EGFR inhibitor(irreversible) CL-387,785 were obtained from EMD-Calbiochem (Cambridge, MA). BCL-2 family inhibitors ABT-737, obatoclax mesylate (GX15-070) and HA14-1 were obtained from Selleck (Houston, TX).

Cellular Cytotoxicity, Viability and Survival Assays

Cellular cytotoxicity and viability assays were performed using CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation (MTS) assay (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instruction at 72 hours after treatment with indicated inhibitors in 10% FBS media. For the studies of cells under 9 days of pretreatment under targeted (EGFR/MET) inhibitors, the indicated inhibitors in the culture media were replenished at least every 2–3 days (which was verified to be indistinguishable from daily TKI replacement) prior to cell harvesting at the end of the inhibitory culture for subsequent cellular assays.

For cell survival assay using crystal violet staining method, H1975 cells or HCC827 cells were treated as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods with indicated TKIs for 6 days, followed by indicated BH3-mimetic inhibition with or without concurrent TKI for 3 extra days.

Time-Lapsed Video Microscopy (TLVM): Image Analysis of Cytoskeletal Functions

HCC827 cells were plated on cell culture dishes in a temperature-controlled chamber at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for TLVM analysis of cytoskeletal functions and determination of cellular mitotic activities as previously described (16) and also in Supplemental Materials.

In Vivo Xenograft Model and Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI) of Human Lung Cancer

Lung cancer xenograft

Firefly-luciferase(luc)-expressing HCC827 and H1975 lung cancer cells, and their corresponding murine xenograft models were established as previously described (see also Supplemental Materials and Methods) according to institution approved protocols and guidelines (16).

Immunohistochemical Analysis

IHC analysis of the tumor xenograft was performed in the Tissue Procurement and Histology Core Facility, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, using anti-human BCL-2 (Abcam), anti-human p-STAT3[Y705] (rabbit monoclonal antibody, D3A7, CST) primary antibodies. Details see also Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Tumor Microarray (TMA)

Human lung cancer tumor microarray was purchased from Zymed-Invitrogen (MaxArray™ Human Lung Cancer Tissue Microarray Slides, Cat. No. 75-4083). IHC staining using anti-human BCL-2 antibody was performed as described above, and graded using 4-tier scoring system (0, 1+, 2+ and 3+) by a dedicated thoracic pathologist (S. H.-K.). For the lung cancer TMA analysis, the TMA used in the analysis consisted of the followings: Squamous Cell (n=25), Adenocarcinoma (n=21), Large Cell (n=3), SCLC (n=5), Carcinoid (n=2), Mesothelioma (n=2).

BCL-2/BCL-XL DNA Transfection and RNA Inerference (RNAi) Studies

Human BCL-2 plasmid vector was a generous gift from Dr. Clark Distelhorst (Case Western Reserve University). Transfection of the BCL-2 expression vector into HCC827 cells was performed using Fugene 6 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche). RNAi knockdown studies were performed using the Thermo Scientific/Dharmacon RNAi Technologies, including siGENOME siRNANT (non-targeting; Cat.#D-001210-02), siRNAs against human BCL-2 (Cat.#L-003307-00), and BCLXL (Cat.#L-003458-00). For HCC827 cells (Fig. 6A–B), cells were plated at full confluence on 48-well plates, then cultured for 9 days in serum-containing media (a) without inhibitor, or with treatment of (b) Erlotinib alone for 9 days, or (c–f) Erlotinib together with the followings in combination: (c) ABT-737 (2μM) concurrently at Day 0, (d) siRNA-non-targeting (siNT), (e) siRNA-BCL-2, and (f) dual siRNABCL-2/BCL-XL RNAi knockdown. Cells were then fixed in methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet as above at the end of Day 9 to visualize the early TKI-resistant tumor survivor cells emerged under various conditions. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

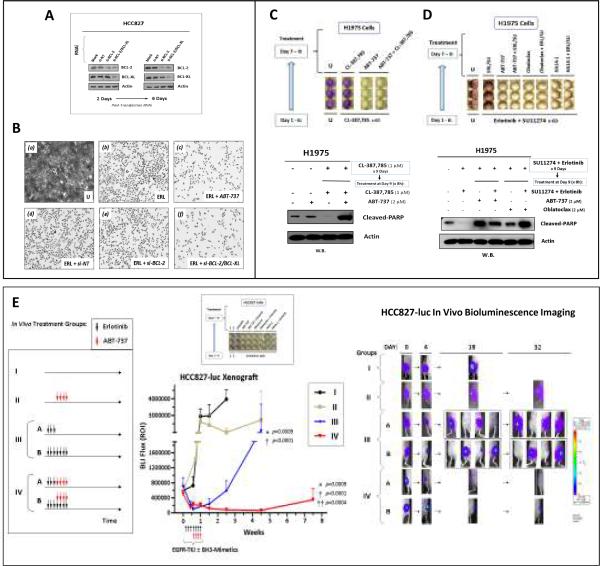

Figure 6. BH3-mimetics therapeutic inhibition of the BCL-2/BCL-XL programmed cell death pathway “Achilles' heel” to eradicate “early” TKI-resistant lung tumor survivor cells.

A, siRNA-mediated knockdown of BCL-2 and BCL-XL in HCC827 cells. WCLs at day 2 and day 6 post-siRNA transfection were then extracted for Western blotting to verify efficient gene knockdown of the target protein(s) expression.

B, BCL-2/BCL-XL RNAi knockdown or BH3-mimetic ABT-737 (2μM) in conjunction with erlotinib (1μM), remarkably suppressed the emergence of “early” EGFR-TKI resistant tumor-evader cells in HCC827. Representative photomicrographs from the triplicate experiments are shown here. Mag: 50×.

C, Proapoptotic BH3-mimetic ABT-737 eradicated the H1975 early tumor prosurvival resistance against CL-387,785. H1975 cells that were pretreated with 6 days of CL-387,785(1μM) were replated at full confluence, followed by further treatments as indicated for 3 additional days in triplicate, either with CL-387,785(1μM), ABT-787(2μM), or ABT-737+CL-387,785, followed by crystal violet cell staining (Top). U, Untreated control. (Bottom), Induction of proapoptotic marker cleaved-PARP by BH3-mimetic in the CL-387,785-resistant early tumor survivor H1975 cells.

D, ABT-737, Obatoclax and HA14-1 eradicated the H1975 early tumor prosurvival resistance against dual-TKIs inhibition by erlotinib/SU11274 (ERL/SU). The experiment was performed with H1975 cells similar to (C) above, except that cells were pre-treated with dual EGFR-MET inhibitors here, i.e. Erlotinib(1μM)/SU11274(1μM). B H 3-mimetic used in treatment Days 7–9 were all 2μM in concentration. (Top), Crystal violet cell survival staining assay. (Bottom), BH3-mimetic treatment of the dual ERL/SU-resistant tumor cells induced a proapoptotic response.

E, In vivo EGFR inhibition with erlotinib in conjunction with BH3-mimetic ABT-737 led to significantly more durable tumor response and prolonged remission in HCC827-luc lung adenocarcinoma xenograft. Left: Schematic outline of treatment conditions of the in vivo HCC827-luc xenografts. Middle (Upper): In vitro HCC827_ERL-D9.R early resistant TKI-evader cells emerged after 6 days of erlotinib(1μM) treatment, were eradicated by co-targeting BH3-mimetic inhibition using ABT-737(2μM), Obatoclax(2μM) or HA14-1(2μM)+/-ongoing erlotinib from days 7–9. Middle (Lower): In vivo HCC827-luc tumor xenograft growth, under treatment conditions as in Groups I-IV, was monitored by BLI as described in the Materials and Methods. Error bar, ± SEM.

Erlotinib-alone (III) vs ABT-737+Erlotinib (IV): *, p=0.0009. Erlotinib-alone (III) vs Diluent Control (I), p<0.0001 (†); ABT-737+Erlotinib (IV) vs Diluent Control (I), p<0.0001 (†). Group II (ABT-737-alone) vs Group IV (ABT-737+Erlotinib), p=0.0004 (††).

Right, BH3-mimetic ABT-737 in vivo treatment in conjunction with EGFR-TKI (Group IV) significantly abolished lung tumor recurrence.

Statistical Analysis

In the BCL-2 transfection study and erlotinib cellular cytotoxicity assay in the HCC827 cells (Fig. 5D), the results under each transfection condition were first summarized by the area under the curve (AUC). The differences of AUC between transfection conditions were then examined by Z-test. Statistical data analysis of the in vivo study using HCC827-luc xenograft murine model (Fig. 6E) was performed using the Mixed Model to examine the difference of read-out (BLI-ROI) among the four study groups (I – IV), by the in vivo xenograft growth rate - changing rate over time (i.e. the change of read-out [BLI-ROI] divided by time [day]). To ensure the normality assumption for the mixed model used is satisfied, the read-outs were transformed by natural log function, i.e. loge(readout), prior to fitting the data using Mixed Model. Tumor recurrence was defined as 20% increase of tumor BLI-flux from the nadir and the difference of recurrence rates between Group II (ABT-737 alone), Group III (Erlotinib alone) and Group IV (ABT-737 plus Erlotinib) was examined by Fisher's exact test. All tests were two-sided and p-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

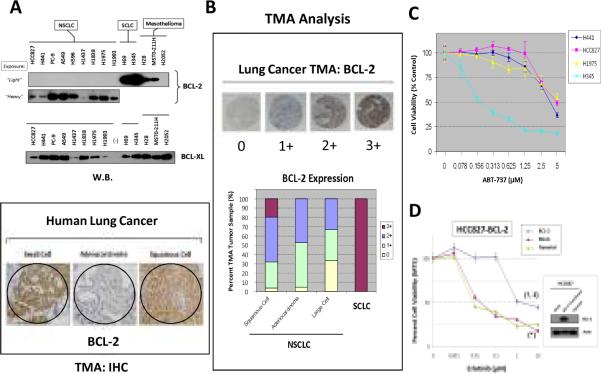

Figure 5. BCL-2/BCL-XL signaling expression and inhibition in lung cancer.

A, BCL-2/BCL-XL expression in lung cancer. Upper panel: BCL-2 and BCL-XL expression in thoracic malignancy cell lines. Lower panel: BCL-2 TMA-IHC staining in SCLC, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. B, Pattern of lung cancer TMA BCL-2 expression. C, Cell viability assay by ABT-737 in HCC827, H441 and H1975 (NSCLC) and H345 (SCLC) cells. D, Forced BCL-2 overexpression in HCC827 cells desensitized the cells to erlotinib. BCL-2-transfected vs mock-transfected cells: †, p<0.0001, or vs parental cells: ‡, p<0.0001. Mock-transfected vs parental cells: *, p=0.99.

RESULTS

Tumor resistance emerged “early” from EGFR-reversible-TKI-sensitive lung adenocarcinoma evading erlotinib: MET-independent BCL-2/BCL-XL signaling

The lung adenocarcinoma cell lines HCC827 and PC-9 are both highly sensitive to reversible-EGFR inhibitors (erlotinib/gefitinib), owing to the oncogenic sensitizing EGFR exon 19 deletion (E746_A750 del). Here, we focused to study the “early” molecular alterations in tumor cells under TKI treatment, in an attempt to uncover potential therapeutic “Achilles' heel” for the tumor cells that may survive the TKI within the early time-window.

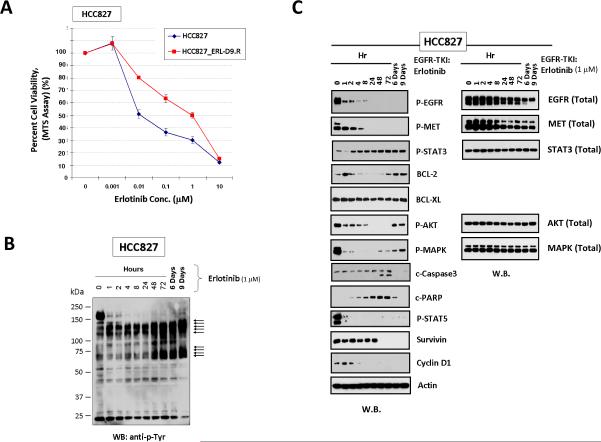

We first adopted the HCC827 cell line in the in vitro “early” TKI-resistance studies, with the cells cultured under ongoing erlotinib (1μM) inhibitory treatment up to 9 days. We chose the concentration of erlotinib to be used at approximately IC70–75 in the 72-hrs cell viability assay. By Day 9 of inhibition, there were cell subpopulations (“early” survivors, HCC827_ERL-D9.R) that evaded and survived the TKI treatment. These “early” survivor cells exhibited a dramatic shift of TKI-sensitivity phenotype towards higher resistance (~100-fold), compared with the TKI-naïve parental cells (Fig. 1A). After an initial inhibited state, there was also reactivated BCL-2/BCL-XL, within the background of a tyrosinephosphoproteomic reactivated cellular state of a unique profile different from the parental cells (Fig. 1BC). Importantly, the tumor cells that survived up to days 6–9 of the EGFR-TKI treatment evidently signaled independently of EGFR and MET (Fig. 1C). Following an initial inhibitory period, we observed a rather early p-STAT3[Y705] reactivation despite ongoing erlotinib treatment. These restored prosurvival-antiapoptotic markers correlated well with time-dependent downregulated cleaved-caspase 3 and cleaved-PARP, indicative of a suppressed caspase-dependent intrinsic apoptosis mechanism among these TKI-evader cells. These results were further verified in PC-9 cell line, with the erlotinib-surviving PC-9 cells (PC-9_ERL-D9.R) at Day-9 inhibition exhibiting MET-independent upregulated p-STAT3[Y705]/BCL-2/BCL-XL signaling, and “early” TKI-resistance (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Targeted inhibition of EGFR-TKI-sensitive HCC827 lung adenocarcinoma cells resulted in emergence of “early” tumor TKI-resistant evader cells with MET-independent prosurvivalantiapoptotic signaling.

A, Significant shift of cell viability towards insensitivity in HCC827 cells that survived 9 days of erlotinib (1μM) treatment. HCC827_ERL-D9.R cells displayed ~100-fold increase in IC50 corresponding with a dramatically higher resistant phenotype against the EGFR-TKI. B, Activated tyrosine-phosphoproteome of early resistant HCC827 cells (HCC827_ERL-D9.R) evading erlotinib up to 9 days. C, Activation of p-STAT3[Y705]/BCL-2/BCL-XL signaling in HCC827_ERL-D9.R cells.

EGFR-irreversible-TKI-sensitive lung adenocarcinoma H1975 cells also demonstrated “early” tumor resistant evasion from CL-387,785

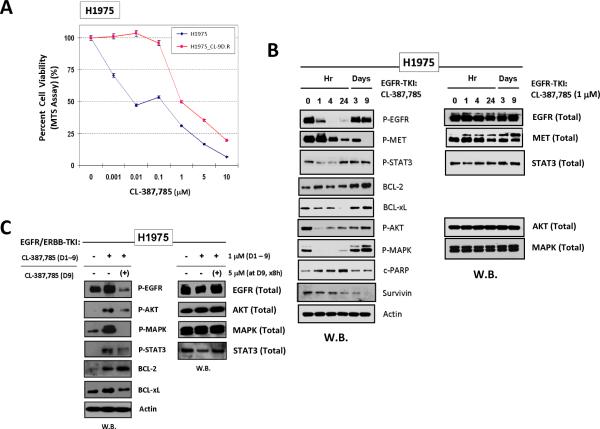

We also tested the H1975 cell line against the irreversible-EGFR-TKI CL-387,785 as an alternate model. Similarly, the “early” TKI-surviving H1975 cells (H1975_CL-D9.R) that were harvested after 9 days of CL-387,785 (1μM) exposure were found remarkably more resistant (Fig. 2A), accompanied with a prosurvival-antiapoptotic signaling upregulation as early as beyond Day 3 of inhibition (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the findings in both HCC827 and PC-9 cells, the H1975_CL-D9.R cells also signaled independent of MET. Intriguingly, the H1975_CL-D9.R cells were found to exhibit reactivated p-EGFR[Y1068] beyond Day 3 and onwards despite ongoing CL-387,785, in the presence of complete p-MET inhibition. Thus, the downstream prosurvival-antiapoptotic signaling in the survivor cells may still be at least partially driven by EGFR signaling. We verified that the reactivated EGFR phosphorylation, and its downstream signals emerged in the H1975_CL-D9.R cells, could be inhibited by a higher concentration (5μM) of the same inhibitor (Fig. 2C). Nonetheless, p-STAT3 and BCL-2 were not effectively inhibited by the retreatment, highlighting their potential importance in promoting the cellular resistant survival, independent of both EGFR and MET signaling.

Figure 2. Targeted inhibition of irreversible EGFR-TKI-sensitive H1975 lung adenocarcinoma cells also results in “early' emergence of tumor resistant escape survivor cells with activated prosurvival-antiapoptotic signaling.

A, Significant resistant shift of cell viability in H1975 cells that survived 9 days of CL-387,785 treatment. B, Activation of p-STAT3[Y705]/BCL-2/BCL-XL signaling in H1975 cells that survived 9 days of CL-387,785 treatment. C, Reactivated p-EGFR and downstream signaling in Day 9-resistant-survivors H1975 cells against CL-387,785 (1μM) could be inhibited by higher dose of CL-387,785 (5μM) in retreatment, but not p-STAT3 or BCL-2.

Early EGFR-TKI resistance exhibited “adaptive” phenotypes that were highly “reversible”

Using TLVM analysis, we found that the HCC827_ERL-D9.R exhibited a cellular “quiescence-like” state, with dramatically inhibited proliferative and cytoskeletal functions while in evasion against erlotinib. Promptly after erlotinib-withdrawal, we found that the early resistant cells could readily be reverted to a highly activated state of cellular motility (Fig. 3A) and mitotic proliferation (Fig. 3B)(see also Supplemental Movies). We further tested to see if the Day-9 “early” resistant cells could maintain their resistant phenotype after a brief period of TKI withdrawal. Interestingly, after only 7 days of withdrawal of the corresponding TKIs, both HCC827_ERL-D9.R and H1975_CL-D9.R cells quickly reverted back to a highly TKI-sensitive phenotype, indistinguishable from parental cell populations respectively (Fig. 3C, E). Importantly, upon a washout period of TKI-withdrawal, these early resistant escape survivor tumor cells re-exhibited TKI-induced p-EGFR inhibition as in the TKI-naïve parental cells (Fig. 3D).

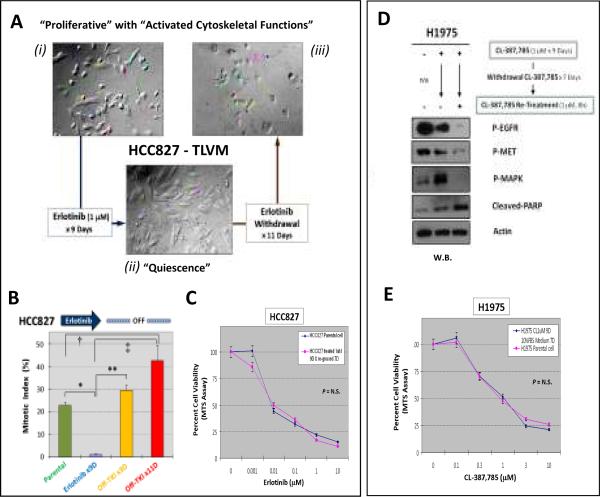

Figure 3. “Adaptive” emergence of “early” TKI-resistant tumor survivor cells in HCC827 under erlotinib, and H1975 under CL-387,785 inhibitory pressure.

HCC827 cells (A–C): (A) TLVM: HCC827_ERL-D9.R cells exhibited a “quiescence-like” state with highly inhibited cell proliferation as well as cellular cytoskeletal functions that were both readily reversible upon TKI-washout for 11 days. (B) Cell mitotic index (M.I.) of HCC827 cells under various treatment conditions. Error bar, S.E.M. (n=4). *, p<0.0001; **, p=0.002; †, p=0.03; ‡, p=0.008. (C) HCC827_ERL-D9.R cells were resensitized to erlotinib inhibition after 7 days of TKI-washout culture conditions, indistinguishable from the parental HCC827 cells sensitivity (p>0.05, N.S.).

H1975 cells (D–E):(D) H1975_CL-D9.R cells were resensitized to TKI in cellular signaling inhibition promptly upon withdrawal of CL-387,785. (E) H1975_CL-D9.R cells were resensitized to CL-387,785 inhibition upon 7 Days of TKI-washout, indistinguishable from the parental H1975 cells sensitivity (p>0.05, N.S.).

In vivo activated STAT3/BCL-2 prosurvival-antiapoptotic signal axis in “early” TKI-resistant lung tumor survivor cells

We extended our studies using in vivo xenograft model to examine tumor cells that survived initial treatment with targeted RTK-inhibitors. HCC827 xenograft was inhibited with erlotinib for 3 days, during which remarkable tumor response was evident as expected. Consistent with our in vitro data, the STAT3 downstream transcriptional target BCL-2 expression was found induced in the TKI-evading survivor cells (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, these early TKI-resistant cells were localized along the peripheral rind of the tumor xenograft (Fig. 4A–B). P-STAT3[Y705] was predominantly membranous and less so cytoplasmic in the untreated HCC827 cells. Conversely, the activated p-STAT3 signal was predominantly nuclear in the residual HCC827 tumor early survivor cells circumscribing along the xenograft periphery (Fig. 4B).

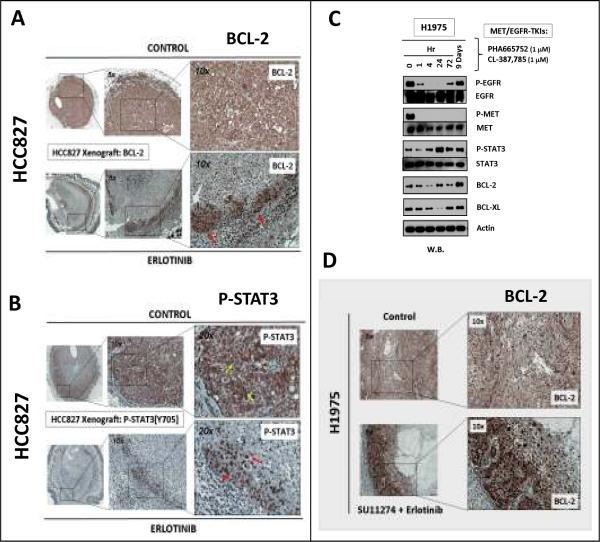

Figure 4. In vivo xenograft lung tumor survivor cells evading against targeted inhibitors, with activated p-STAT3/BCL-2 antiapoptotic signaling.

In vivo HCC827 xenograft model treated with erlotinib (n=6) revealed “early” TKI-resistant tumor survivor cells (A) with induced BCL-2 expression especially in the nuclear subcellular localization (red arrows), and (B) with nuclear translocation (red arrows) of p-STAT3[Y705] from the untreated cytoplasmic localization (yellow arrows). C, Combined MET-EGFR TKIs treatment of H1975 cells in vitro also led to an induction of MET-independent activated p-STAT3[Y705], and BCL-2/BCL-XL signaling in TKI-evading survivor cells against 9 days of combined-TKIs (PHA665752 [1μM] and CL-387,785 [1μM]). D, Induced BCL-2 expression in H1975-xenograft residual dual SU11274/erlotinib-TKI-evader survivor cells.

Past studies suggested that non-T790M-EGFR mediated acquired gefitinib/erlotinib resistance in sensitive-lung cancer cells may include genomic MET amplification (8, 9) or HGF overexpression (31). Currently, there are various clinical trials investigating the strategy of combining EGFR- and MET inhibitors to enhance therapeutic efficacy and overcome acquired EGFR-TKI resistance in NSCLC. We have previously characterized the MET inhibitors SU11274 (20) and PHA665752 (21) in lung cancer novel therapy, and will be utilized in the present study. Similar to the EGFR-TKI monotherapy model above, there was an upregulated BCL-2/BCL-XL prosurvival-antiapoptotic signaling in H1975 TKI-evader cells after 9 days of dual CL-387,785/PHA665752 inhibition, alongwith restored p-STAT3 activation (Fig. 4C), and associating with a more TKI-resistant phenotype in the evader cells (p=0.0118)(Supplemental Fig. 2).

We recently reported the efficacy of combined SU11274-erlotinib (MET-EGFR/ERBB TKI) in vivo H1975 xenograft model in overcoming T790M-EGFR drug-resistance, with resultant near-complete BLI-radiographic complete response (16). Here, we further evaluated the microscopic residual TKI-evading H1975-luc tumor cells and found they resided primarily along the tumor periphery juxtaposing the murine host-microenvironment. These TKI-evading survivor tumor cells also exhibited upregulated BCL-2 expression (Fig. 4D).

BCL-2 signal pathway expression and its potential therapeutic utility in NSCLC inhibition by BCL-2 Homology Domain 3(BH3)-mimetic

BCL-2 was found to be expressed at varying levels in NSCLC cell lines and lung tumor tissues, albeit at a significantly lower level range than in SCLC (Fig. 5A–B). Interestingly, unlike BCL-2, the expression levels of BCL-XL appeared to be more comparable among NSCLC and SCLC cell lines (Fig. 5A). The TMA analysis showed that BCL-2 expression in NSCLC was primarily nuclear, while that in SCLC was strongly positive both nuclear and cytoplasmic. Stronger BCL-2 nuclear expression was observed in squamous cell comparing to adenocarcinoma subtype. Our results above provide a rationale to target BCL-2 family signaling through proapoptotic BH3-mimetic, such as ABT-737 (32–34), in order to optimize targeted therapies. ABT-737 has been well-characterized recently and shown to antagonize BCL-2/BCL-XL, thereby inducing a proapoptotic effect through the mitochondrial intrinsic apoptosis pathway. The NSCLC cell lines were relatively insensitive to ABT-737 (IC50>5μM), whereas the SCLC H345 cell line tested was as expected highlysensitive (IC50<0.2μM)(Fig. 5C). HCC827 cells with forced overexpression of transfected BCL-2 was sufficient to induce a significantly higher erlotinib-resistance, with ~100-fold increase in IC50 (Fig. 5D).

ABT-737 inhibition in concert with targeted kinase inhibitors, both in vitro and in vivo, eradicated “early” TKI-resistant tumor evaders and further inhibited subsequent tumor recurrence

We hypothesized that preemptive inhibition and eradication of “early” resistant tumor cells in RTK targeted therapy may impact on the long-term outcome of targeted therapy. We adopted RNAi knockdown of BCL-2/BCL-XL using siRNA methods here to test in parallel with ABT-737 (Fig. 6A–B). Dramatic reduction in the early TKI-resistant tumor survivor cells was achievable by dual BCL-2/BCLXL RNAi knockdown in conjunction with erlotinib, but not by mere knockdown of BCL-2 alone. ABT-737, when used concurrently with erlotinib to inhibit HCC827 cells, also dramatically reduced emergence of early TKI-resistant tumor survivor cells against erlotinib (Fig. 6B–c).

We further performed in vitro ABT-737 inhibition studies on the NSCLC H1975 TKI-evading tumor cells that were primed to upregulate BCL-2/BCL-XL prosurvival signaling by (i) EGFR/ERBB inhibitor (CL-387,785)(Fig. 6C), and (ii) dual EGFR-MET inhibitors (erlotinib plus SU11274)(Fig. 6D). ABT-737, at a concentration relatively insensitive against H1975 parental cells, completely eradicated the early CL-387,785-resistant H1975 evader cells (Fig. 6C, upper panel), either alone or in combination with CL-387,785. Importantly, we showed that the “early” TKI-resistant tumor cells were primed to be more susceptible to ABT-737 inhibition, exhibiting a much enhanced proapoptotic marker cleaved-PARP induction by the BH3-mimetic (Fig. 6C, lower panel). Moreover, the dual-TKI-resistant H1975_ERL/SU-D9.R tumor cells could also be targeted by ABT-737 to further induce apoptosis (Fig. 6D). Other BH3-mimetic BCL-2 family inhibitors tested in our study, obatoclax (35) and HA14-1 (36), also showed efficacy (Fig. 6D). Similar to H1975 cells, early TKI-evading resistant HCC827 cells also displayed therapeutic susceptibility to BH3-mimetic in vitro (Fig. 6E).

Finally, we tested if the addition of the BH3-mimetic ABT-737 in vivo would prolong the duration of response in erlotinib-treated drug-sensitive HCC827-luc xenograft (Fig. 6E). The in vivo ABT-737 treatment dosage in our study was chosen based on reported literature on the therapeutic range in the tested sensitive cancer models (37). The tumor growth rate in recurrence of the ABT-737+Erlotinib-treated group (IV) was significantly lower than that of the Erlotinib-alone group (III)(p=0.0009)(Fig. 6E, Table 1; also Supplemental Fig. 3). ABT-737-alone (Group II) did not account for the tumor regression and abrogation of tumor recurrence as seen in the ABT-737+Erlotinib group (Group IV)(p=0.0004). Finally, the HCC827 tumor recurrence rates at Days 18 and Day 32 for Group III (Erlotinib-alone) animals were 50%(p=0.014) and 62.5%(p=0.004) respectively, both significantly higher than Group IV (ABT-737+Erlotinib)(0%)(Fig. 6E).

Table 1.

Inhibition of HCC827-luc tumor in vivo xenograft recurrence rates by BH3-mimetic ABT-737 treatment in conjunction with EGFR-Inhibitor (Fig. 6E).

| Treatment Groups | Xenograft Recurrence Rates (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 18 | Day 32 | ||||

| III | A | 50% (2/4) |

50%

*

(4/8) |

75%(3/4) |

62.5%

†

(5/8) |

| B | 50% (2/4) | 50% (2/4) | |||

| IV | A | 0% (0/6) |

0%

(0/12) |

0% (0/6) |

0%

(0/12) |

| B | 0% (0/6) | 0% (0/6) | |||

p=0.014

p=0.004

DISCUSSION

In recent years, molecularly-targeted cancer therapy has renewed our hope for cancer cure. Nonetheless, the challenges of clinical tumor resistance, both intrinsic and acquired, remain formidable and substantially limit long-term efficacy. Classic secondary mutational resistance [e.g. T790M-EGFR against gefitinib/erlotinib in lung cancer (11)], and receptor kinase class-switching [e.g. from EGFR-addiction to MET/HGF (8, 9, 16), IGF1-R (27, 38) or AXL (39) signaling] have been identified in earlier studies that emphasized on “acquired” drug-resistance at “late-stages” of chronic drug treatment. Our study here focuses on the molecular changes of drug-sensitive tumor cell population within the “early” time-window of targeted TKI treatment. We identified and further characterized the “early” adaptive functional TKI-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cells that survived and evaded EGFR/MET-TKI, as early as within 9 days of therapy. During our manuscript preparation, Settleman and coworkers reported the identification of “drug-tolerant state” in cancer cell subpopulations that was maintained through engagement of IGF-1R signaling and an epigenetic alteration of chromatin state that requires the histone demethylase RBP2/KDM5A/Jarid1A (27). Our report here lends further support to the emerging evidence of the existence of tumor cell subpopulations with adaptive resistant-escape under therapeutic inhibitory stress. These early adaptive resistant survivors likely serve as the founder population as minimal residual disease in solid cancers under therapeutic pressure, which ultimately leads to frankly recurrent resistant disease on therapy in the future.

Despite the new insights into non-mutational early resistance (28), detailed underlying regulatory mechanism(s) that directly mediate the emergence of such early resurgent resistant cells against the inhibitors remain to be fully defined. Our study here provided the first evidence that the “early” emergence of resistant tumor survivors evading EGFR/ERBB-MET TKIs were independent of MET receptor signaling activation, contrasting previous reports of MET genomic amplification as acquired resistance mechanism in HCC827 cells that escape “chronic” dose-escalating gefitinib inhibition at “late stages” after many months of treatment (8, 9). We present findings here that the BCL-2-family signaling in the mitochondrial (intrinsic) programmed-cell death pathway may indeed represent the central mechanism as tumor cells' newly-dependent addiction, in promoting “early tumor evasion” to survive targeted therapeutics. Here, we also provided additional in vivo therapeutic study evidence to validate the efficacy of targeting the BCL-2 family antiapoptotic machinery in the residual tumor survivors under TKI(s) therapeutic inhibition (Fig. 6E). Collectively, our results further raise the promise of the feasibility in “drugging” the drug-resistant residual tumor cells (40), particularly within an early therapeutic window-of-opportunity. Hence, targeting the mitochondrial antiapoptotic machinery as the secondary “Achilles' heel” newly-emerged in the early-resistant tumor cells appears to be an attractive therapeutic strategy. On the other hand, concurrent EGFR-TKI and ABT-737 treatment also significantly suppressed the emergence of early TKI-resistant HCC827 cells, evident as early as within 6–9 days (Fig. 6) with the efficacy lasting up to 4–6 weeks (data not shown). We believe that the novel therapeutic strategy in targeting the adaptive drug-evader tumor survivor cells emergent within the “early treatment time-window” is attractive, as these evader cells are most likely more “homogeneous” molecularly than those found eventually as overtly resistant disease after “chronic” TKI inhibition for months. “Late” TKI-resistant tumor cells likely already had undergone divergent resistant molecular evolution in progression, hence more heterogeneous, during the long time lapsed under chronic TKI stress.

Our data suggest that the early tumor survival against TKI is an “adaptive” mechanism, rather than a selection of preexisting resistant cell clones. It remains unclear at present as to what definitively regulates and determines the cell fates early under targeted inhibition, and which cells among the parental drug-sensitive cell population would emerge as resistant survivors in the beginning of the tumor evolution under therapeutic stressors. Nonetheless, the contribution of intrinsic molecular heterogeneity and non-genetic variation within individual cells among the parental cell population may still play at least a partial role in the ultimate cell-fate determination. Interestingly, BCL-2 has recently been implicated as inhibitor of DNA repair mechanism (41–44), which may potentially enhance and facilitate the molecular evolution of tumor progression beyond the “early” non-mutational resistance.

Persistent STAT3 activation has been detected in a variety of hematopoietic malignancies and solid tumors (45–47). We observed phosphorylated-STAT3(p-STAT3) in the residual tumor survivor cells both in vitro and in vivo under targeted kinase inhibitors. Our results suggest that “early” reactivation of STAT3 at tyrosine-705 (important in STAT3 dimerization and subsequent nuclear translocation) may be an important central transcriptional programming event prior to the ultimate resurgence of resistant tumor survivors. Recent attempts to develop therapeutic inhibitors to target STAT3 have proven to be rather difficult. Nonetheless, a number of BH3-mimetic that target the key STAT3 downstream transcriptional targets, such as BCL-2/BCL-XL, have shown promise in preclinical and clinical studies, including ABT-737, and the newer pan-BCL-2 family inhibitors ABT-263, and obatoclax (37, 48, 49). The latter pan-BCL-2 family inhibitors may potentially be more advantageous over ABT-737 in their effective inhibition of MCL-1, shown to induce ABT-737 resistance (50).

To our knowledge, our study represents the first in vivo evidence that therapeutic targeting early resurgent resistant tumor survivor cells evading cancer targeted inhibitors is feasible through inhibiting the mitochondrial antiapoptotic BCL-2/BCL-XL signaling in NSCLC, impacting on the therapeutic outcome. Our results here provide support to further develop BH3-mimetic beyond basally BCL-2 overexpressing tumors such as SCLC and lymphomas, and extend to NSCLC as a therapeutic strategy to unleash the full potential and to optimize long-term clinical outcome of oncogenic kinase inhibitors. We propose that the combinational approach using BH3-mimetic and RTK inhibitors should be investigated further in the context of NSCLC human clinical trial studies.

Precis.

Findings provide a rationale for lung cancer clinical trials to combine BH3 mimetic drugs in combination with receptor kinase inhibitors, based on understanding of how early resistance to this class of inhibitors emerge.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs. Zhenghe Wang, Stan Gerson and George Stark for helpful discussion and suggestions. We also thank Mr. Joseph Molter for technical assistance. This work is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute-K08 Award (5K08-CA102545-05, 3K08-CA102545-05S1)(P.C. Ma), Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, Sol Siegal Lung Cancer Research Grant Program, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (Gene Expression and Genotyping Core, Confocal Microscopy Core, Xenograft and Athymic Animal Core, Tissue Procurement and Histology Core, and Animal Imaging Core Facilities)(P30-CA43703-12), and Northern-East Ohio Small Animal Imaging Resources Program (R24-CA110943).

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer - molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1160–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma PC, Maulik G, Christensen J, Salgia R. c-Met: structure, functions and potential for therapeutic inhibition. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:309–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1023768811842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eder JP, Vande Woude GF, Boerner SA, LoRusso PM. Novel therapeutic inhibitors of the c-Met signaling pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2207–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch TJ, Adjei AA, Bunn PA, Jr., et al. Summary statement: novel agents in the treatment of lung cancer: advances in epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4365s–71s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, Haber DA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–81. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bean J, Brennan C, Shih JY, et al. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20932–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regales L, Balak MN, Gong Y, et al. Development of new mouse lung tumor models expressing EGFR T790M mutants associated with clinical resistance to kinase inhibitors. PLoS One. 2007;2:e810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi S, Ji H, Yuza Y, et al. An alternative inhibitor overcomes resistance caused by a mutation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7096–101. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong KK, Fracasso PM, Bukowski RM, et al. A phase I study with neratinib (HKI-272), an irreversible pan ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2552–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Gale CM, et al. PF00299804, an irreversible pan-ERBB inhibitor, is effective in lung cancer models with EGFR and ERBB2 mutations that are resistant to gefitinib. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11924–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang Z, Du R, Jiang S, et al. Dual MET-EGFR combinatorial inhibition against T790M-EGFR-mediated erlotinib-resistant lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:911–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt L, Duh FM, Chen F, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1997;16:68–73. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christensen JG, Burrows J, Salgia R. c-Met as a target for human cancer and characterization of inhibitors for therapeutic intervention. Cancer Lett. 2005;225:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma PC, Kijima T, Maulik G, et al. c-MET mutational analysis in small cell lung cancer: novel juxtamembrane domain mutations regulating cytoskeletal functions. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6272–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma PC, Jagadeeswaran R, Jagadeesh S, et al. Functional expression and mutations of c-Met and its therapeutic inhibition with SU11274 and small interfering RNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1479–88. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma PC, Schaefer E, Christensen JG, Salgia R. A selective small molecule c-MET Inhibitor, PHA665752, cooperates with rapamycin. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2312–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma PC, Tretiakova MS, MacKinnon AC, et al. Expression and mutational analysis of MET in human solid cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:1025–37. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, et al. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma PC, Tretiakova MS, Nallasura V, Jagadeeswaran R, Husain AN, Salgia R. Downstream signalling and specific inhibition of c-MET/HGF pathway in small cell lung cancer: implications for tumour invasion. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:368–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou HY, Li Q, Lee JH, et al. An orally available small-molecule inhibitor of c-Met, PF-2341066, exhibits cytoreductive antitumor efficacy through antiproliferative and antiangiogenic mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4408–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christensen JG, Zou HY, Arango ME, et al. Cytoreductive antitumor activity of PF-2341066, a novel inhibitor of anaplastic lymphoma kinase and c-Met, in experimental models of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3314–22. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma SV, Lee DY, Li B, et al. A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell. 2010;141:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Workman P, Travers J. Cancer: drug-tolerant insurgents. Nature. 2010;464:844–5. doi: 10.1038/464844a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choong NW, Dietrich S, Seiwert TY, et al. Gefitinib response of erlotinib-refractory lung cancer involving meninges--role of EGFR mutation. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:50–7. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0400. quiz 1 p following 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang Z, Jiang S, Du R, et al. Disruption of the EGFR E884-R958 ion pair conserved in the human kinome differentially alters signaling and inhibitor sensitivity. Oncogene. 2009;28:518–33. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yano S, Wang W, Li Q, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor induces gefitinib resistance of lung adenocarcinoma with epidermal growth factor receptor-activating mutations. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9479–87. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chonghaile TN, Letai A. Mimicking the BH3 domain to kill cancer cells. Oncogene. 2008;27(Suppl 1):S149–57. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason KD, Khaw SL, Rayeroux KC, et al. The BH3 mimetic compound, ABT-737, synergizes with a range of cytotoxic chemotherapy agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:2034–41. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuroda J, Puthalakath H, Cragg MS, et al. Bim and Bad mediate imatinib-induced killing of Bcr/Abl+ leukemic cells, and resistance due to their loss is overcome by a BH3 mimetic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14907–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606176103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trudel S, Li ZH, Rauw J, Tiedemann RE, Wen XY, Stewart AK. Preclinical studies of the pan-Bcl inhibitor obatoclax (GX015-070) in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2007;109:5430–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-047951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manero F, Gautier F, Gallenne T, et al. The small organic compound HA14-1 prevents Bcl-2 interaction with Bax to sensitize malignant glioma cells to induction of cell death. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2757–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeitlin BD, Zeitlin IJ, Nor JE. Expanding circle of inhibition: small-molecule inhibitors of Bcl-2 as anticancer cell and antiangiogenic agents. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4180–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guix M, Faber AC, Wang SE, et al. Acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer cells is mediated by loss of IGF-binding proteins. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2609–19. doi: 10.1172/JCI34588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahadevan D, Cooke L, Riley C, et al. A novel tyrosine kinase switch is a mechanism of imatinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Oncogene. 2007;26:3909–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dannenberg JH, Berns A. Drugging drug resistance. Cell. 2010;141:18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin Z, May WS, Gao F, Flagg T, Deng X. Bcl2 suppresses DNA repair by enhancing c-Myc transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14446–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hou Y, Gao F, Wang Q, et al. Bcl2 impedes DNA mismatch repair by directly regulating the hMSH2-hMSH6 heterodimeric complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9279–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Q, Gao F, May WS, Zhang Y, Flagg T, Deng X. Bcl2 negatively regulates DNA double-strand-break repair through a nonhomologous end-joining pathway. Mol Cell. 2008;29:488–98. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao J, Gao F, Zhang Y, Wei K, Liu Y, Deng X. Bcl2 inhibits abasic site repair by down-regulating APE1 endonuclease activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9925–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708345200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bowman T, Garcia R, Turkson J, Jove R. STATs in oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2000;19:2474–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Darnell JE. Validating Stat3 in cancer therapy. Nat Med. 2005;11:595–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0605-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kutuk O, Letai A. Alteration of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is key to acquired paclitaxel resistance and can be reversed by ABT-737. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7985–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gong Y, Somwar R, Politi K, et al. Induction of BIM is essential for apoptosis triggered by EGFR kinase inhibitors in mutant EGFR-dependent lung adenocarcinomas. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yecies D, Carlson NE, Deng J, Letai A. Acquired resistance to ABT-737 in lymphoma cells that up-regulate MCL-1 and BFL-1. Blood. 2010;115:3304–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.