Abstract

Background

Recent studies based on self-reported data suggest that retirement may have beneficial effects on mental health, but studies using objective endpoints remain scarce. This study examines longitudinally the changes in antidepressant medication use across the 9 years spanning the transition to retirement.

Methods

Participants were Finnish public-sector employees: 7138 retired at statutory retirement age (76% women, mean age 61.2 years), 1238 retired early due to mental health issues (78% women, mean age 52.0 years), and 2643 retired due to physical health issues(72% women, mean age 55.4 years). Purchase of antidepressant medication four years prior to and four years after retirement year were based on comprehensive national pharmacy records in 1994-2005.

Results

One year before retirement, the use of antidepressants was 4% among those who would retire at statutory age, 61% among those who would retire due to mental health issues, and 14% among those who would retire due to physical health issues. Retirement-related changes in antidepressant use depended on the reason for retirement. Among old-age retirees, antidepressant medication use decreased during the transition period (age- and calendar-year-adjusted prevalence ratio for antidepressant use 1 year after vs. 1 year before retirement = 0.77 [95% confidence interval = 0.68 – 0.88]). Among those whose main reason for disability pension was mental health issues or physical health issues, there was an increasing trend in antidepressant use prior to retirement and, for mental health retirements, a decrease after retirement.

Conclusions

Trajectories of recorded purchases of antidepressant medication are consistent with the hypothesis that retirement is beneficial for mental health.

Due to population aging, the proportion of retired people is increasing rapidly throughout the industrialized world. It has been projected that if labor force participation remains unchanged, the number of retirees per worker will double by 2050 in most developed countries.1 Many societies have been grappling with the issue of social security solvency, and health in retirement is widely discussed.2, 3

Previous research on the health effects of transition to retirement has provided inconsistent evidence. Some studies suggest that mental health is better in retirement,4-12 whereas some report that it is worse,13-16 and still others found no change in relation to retirement.17-20 Some studies,5,12 but not all,4 suggest that retirement is more beneficial for employees in high-SES compared with low-SES groups. The reasons for these inconsistencies may be due to differences in study design. Indeed, the few prospective studies with information about each worker’s health trajectory prior to the retirement transition, as well as following retirement, consistently suggest that retirement has a beneficial impact on perceived mental well-being and health.4,11,12,21 It is unclear, however, whether this finding is robust with respect to health indicators that do not rely only on self-reports.

To examine potential influences of retirement on objectively assessed mental health, we studied whether transition to retirement is associated with changes in antidepressant medication use as indicated by annual perscription records during the four years prior to and four years following the retirement year. We hypothesised that retirement would be associated with a decline in the levels of antidepressant use after taking the secular trend in rising antidepressant prescriptions into account (eFigure 1, http://links.lww.com).22 As a validity check for our hypothesis, we also examined pre- and post-retirement trajectories in prescription use for diabetes medications. Our a priori hypothesis was that there would be no relation between retirement and diabetes medication use. Although diabetes prevalence increases with age, retirement is unlikely to have immediate effects on diabetes risk.4

METHODS

Context of the study

The National Health Insurance scheme (NHI) is part of the Finnish social security system covering all citizens regardless of age, wealth, or employment status (i.e. employed, unemployed, or retired). Retirement per se has no impact on prescription reimbursements. After a fixed deductible per purchase (10 euros in 2005), NHI reimburses 50% of the costs of filled prescriptions. This basic reimbursement applies to antidepressants and drugs to treat diabetes. However, diabetic patients are eligible for special reimbursement to get a 100% refund of medicine costs exceeding 5 euros (in 2005). If the annual medicine costs that are not covered by NHI exceed a certain limit (607 euros in 2005), the scheme member gets all drugs beyond that limit free during that year. Also, in case of financial difficulties or great burden of diseases, it is possible to apply for extra financial support for medicine costs from local social security authorities.23

The Finnish pension provision consists of an employment-based, earnings-related pension plus a residence-based, national pension that guarantees a minimum income. As an example, the earnings-related pension is about 57% for a person with average wage and a work history of 40 years.24 According to the public sector employees’ pension act, the statutory retirement age is generally from 63 to 65 years (63 to 68 years from 2005 onwards), although the age is lower for specific groups (e.g., 60 years for primary school teachers, 58 for practical nurses). A disability pension may be granted if, due to an illness, the employee cannot continue working even after attempts at rehabilitation, re-education, or assistance. Employees may apply for disability pension in the event of more than 300 reimbursed sickness absence days (Sundays excluded) during two consecutive years on the basis of the illness causing work disability. Around 80% of all disability pension applications are accepted.25

Study design and participants

We studied the changes in mental health by assessing trajectories of filled antidepressant prescriptions during a 9-year period around retirement, and comparing the results with trajectories of filled diabetes medication prescriptions in the same cohort. The participants are from the Finnish Public Sector Study cohort: a total of 151,618 employees who have been employed in 10 municipalities or 6 hospital referral districts for at least six months in any year from 1991 to 2005.26 Data for cohort members were successfully linked to employers’ records and comprehensive national health registers through unique personal identification codes, which are assigned to all citizens in Finland.

Of the cohort members, we identified full-time retirees who retired at statutory retirement age, and those who retired early on health grounds between 1995 and 2004, and who were alive at least one year after the retirement—a total of 13,559 persons. These initial inclusion criteria were selected in order to allow for at least a 3-year follow-up around retirement (i.e. from one year prior to one year after retirement). In case of entitlement to several pensions from different pension schemes at different times, the first one awarded was selected. We excluded the employees of one town, where the medication costs were paid by the employer during employment (n = 2540). Thus, the analytic sample comprised of 11,019 retirees (75% women). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health.

Assessment of retirement

Data on retirement were obtained from the Finnish Centre for Pensions, which coordinates all earnings-related pensions for permanent residents in Finland.27 All gainful employment is insured in a pension plan and accrues a pension; thus the pension data with successful linkage were available for all participants. The dates for starting to receive old-age or disability pension were obtained for all participants from 1994 through 2005, irrespective of the participants’ employment status or workplace at follow-up. We analyzed those participants whose main medical cause for retirement assigned by the treating physician was mental illness (WHO International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision, ICD-10 codes F00-F99) separately from employees retiring due to physical causes (all other ICD-codes).

Assessment of antidepressant use and use of diabetes medication

We determined antidepressant use for each year of the 9-year observation period using the nationwide Drug Prescription Register maintained by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland. The data include the dates of purchase of all drugs in the World Health Organization’s Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification and the corresponding defined daily dosages (DDDs). For each year of observation, we defined antidepressant use as the purchase of antidepressants (ATC code N06A) of at least 30 daily doses.

In a similar way, the annual purchases of diabetes medication (ATC code A10) of at least 30 defined daily doses were retrieved from the Drug Prescription Register. Persons with diabetes can be entitled to special reimbursement for treatment of diabetes, after which the drugs for diabetes are free of charge after a fixed deductible per purchase. Patients who apply for special reimbursement must submit a detailed medical certificate prepared by the treating physician. Altogether 74% of employees purchasing diabetes medication during the year of retirement transition were entitled to special reimbursement for the cost of diabetes medication.

Assessment of pre-retirement covariates

From the employers’ registers we obtained information on sex, socioeconomic status (SES), geographic area (Southern, Middle, Northern Finland, based on the location of the workplace), and type of employer (town or hospital). SES was categorized according to the occupational-title-based classification of the Statistics Finland to upper-grade non-manual workers (e.g. teachers, physicians), lower-grade non-manual workers (e.g. registered nurses, technicians), and manual workers (e.g. cleaners, maintenance workers),28 as determined by the last occupation during the 3 years preceding retirement. Long-term sickness absence (yes or no) was assessed by combining records of temporary disability pension with records of sickness absence (lasting at least 10 days) during the year preceding retirement, obtained from the Social Insurance Institution. As in our earlier studies,26 the presence of chronic diseases (yes or no) in retirement was defined by entitlement to special reimbursement for the costs of medication needed to treat diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, coronary heart disease, or heart failure in retirement, obtained from records at the Social Insurance Institution.

Statistical analysis

The analyses were based on a 9-year observation window, with the year of retirement as year 0 and the four years of observation both before and after retirement as years −4 to −1 and years +1 to +4. A total of 0.9% of the statutory retirees, 2.2% of those who retired due to mental health issues, and 4.4% of those who retired due to physical issues died during years +2 to +4. Mortality was not differential in terms of baseline antidepressant use.

To examine changes in the likelihood of antidepressant treatment, we applied a repeated-measures logistic regression analysis using the generalized estimating equations (GEE) method with autoregressive correlation structure.29 GEE takes into account the intra-individual correlation between measurements and is not sensitive to missing measurements. We chose the autoregressive correlation structure because it assumes correlations between time points to be greater the nearer the measurements are to each other. The autoregressive model also yielded a slightly better fit than the exchangeable working correlation model. We calculated the annual prevalence estimates in order to plot the trajectory of antidepressant treatment in relation to retirement, adjusting the models for age at retirement and calendar year.22 Similarly, we calculated the annual prevalence estimates of use of diabetes medication, and used the trajectory as a reference.

The life-course approach proposes that the impact of retirement and other life transitions may depend on the proximity to the transition.30, 31 Thus, we distinguished the three periods of the retirement process as follows: the pre-retirement period (years −4 to −2), the transition period (years −1 to +1), and the post-retirement period (years +2 to +4). This categorization also provided us with sufficient power to test whether there was a change in trend of antidepressant use during each period. We used time as a continuous variable in the analyses, and entered the interaction term (time*period) into the binomial or (where appropriate) Poisson regression model to evaluate whether the trend in antidepressant use was different among the three periods.32 We calculated prevalence differences and prevalence ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to express change in antidepressant use between the first and last year within each of the three periods, adjusting the models for age at retirement and calendar year.

We tested the robustness of the findings first by investigating whether the pre-retirement covariates modified the shape of the trajectory by entering the second-level interaction term “effect modifier*time*period” into the regression model and calculated the prevalence ratios of the trend in antidepressant use within the pre-retirement, retirement transition, and post-retirement periods. We additionally adjusted the models for pre-retirement covariates, although stable factors are not plausible confounders for time-dependent trajectories.

Finally, we ran sensitivity analyses to test (1) whether there was a change in trend between the pre-retirement period and the retirement transition in a subgroup of statutory retirees who had complete data for all years of the pre-retirement and transition periods (n = 4306), (2) whether the findings were sensitive to the specific dose selected to define antidepressant use (i.e. 30 vs. any, at least 90 or 180 defined daily doses per year) or the number of purchases made, and (3) whether there were differences in the number of filled prescriptions by socioeconomic status.

All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS 9.1.3 statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Between 1995 and 2004, 7138 participants retired at statutory retirement age (mean = 61.2; range = 55-67 years) and 3881 retired early on health grounds, 1238 of whom were awarded a disability pension due to mental health issues (mean age = 52.0; range = 24-63 years) and 2643 due to physical health issues (mean age = 55.4; range = 23-64 years). Women, participants who retired before 60 years of age, and participants who had chronic or disabling diseases were more likely to receive antidepressant treatment prior to retirement than their male and older counterparts with no chronic or disabling diseases (Table1). During the follow-up, 1-3% of the retirees made only a single purchase of antidepressants, whereas the majority of participants who were on antidepressants filled at least five prescriptions (eTable 1, http://links.lww.com). The number of filled prescriptions of antidepressants did not vary between socioeconomic groups. Altogether 61 % of those retiring early due to mental disorders were on antidepressant treatment one year prior to retirement. The corresponding prevalence was 4% in old age retirees and 14% among those retiring early due to physical causes. The retirement cohorts differed in terms of background characteristics, supporting the rationale for analyzing the three cohorts separately (Table 2).

Table 1.

Antidepressant usea by characteristics of the study sample one year before retirement

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Antidepressant treatmentb No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| All | 11,019 | 1452 (13) |

| Sex | ||

| men | 2723 (25) | 276 (10) |

| women | 8296 (75) | 1176 (14) |

| Age at retirement (years) | ||

| ≤ 60 | 6554 (59) | 1211 (19) |

| > 60 | 4465 (41) | 241 (5) |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| upper grade non-manual | 3305 (30) | 406 (12) |

| lower grade non-manual | 4361 (40) | 635 (15) |

| manual | 3352 (30) | 411 (12) |

| Employer | ||

| Town | 8148 (74) | 1086 (13) |

| Hospital district | 2871 (26) | 366 (13) |

| Area of employment | ||

| Southern Finland | 7436 (67) | 975 (13) |

| Middle Finland | 1781 (16) | 223 (13) |

| Northern Finland | 1802 (16) | 254 (14) |

| Presence of chronic disease | ||

| None | 8086 (73) | 1041 (13) |

| At least 1 | 2933 (26) | 411 (14) |

| Long-term sickness absence | ||

| None | 5865 (53) | 216 (4) |

| At least 1 | 5154 (47) | 1236 (24) |

| Type and main cause for retirement | ||

| Retirement at statutory age | 7138 (65) | 317 (4) |

| Early retirement due to mental causes | 1238 (11) | 761 (61) |

| Early retirement due to physical causes | 2643 (24.) | 374 (14) |

Annual purchase of antidepressants over 30 daily defined dosages per year.

Row percentages.

Table 2.

Type of retirement and main medical cause of early retirement by background characteristics one year before retirement

| Statutory retirement |

Early retirement due to mental causes |

Early retirement due to physical causes |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Sex | |||

| men | 1695 (24) | 278 (22) | 750 (28) |

| women | 5443 (76) | 960 (78) | 1893 (72) |

| Age at retirement (years) | |||

| ≤ 60 | 3185 (45) | 1157 (93) | 2212 (84) |

| > 60 | 3953 (55) | 81 (7) | 431 (16) |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| upper grade non-manual | 2610 (37) | 323 (26) | 372 (14) |

| lower grade non-manual | 2799 (39) | 569 (46) | 993 (38) |

| manual | 1728 (24) | 346 (28) | 1278 (48) |

| Employer | |||

| Town | 5095 (71) | 960 (78) | 2093 (79) |

| Hospital district | 2043 (29) | 278 (22) | 550 (21) |

| Area of residence | |||

| Southern Finland | 4888 (68) | 807 (65) | 1741 (66) |

| Middle Finland | 1248 (17) | 179 (14) | 354 (13) |

| Northern Finland | 1002 (14) | 252 (20) | 548 (21) |

| Presence of chronic disease | |||

| None | 5477 (77) | 925 (75) | 1684 (64) |

| At least 1 | 1661 (23) | 313 (25) | 959 (36) |

| Long-term sickness absence | |||

| None | 5368 (75) | 109 (9) | 388 (15) |

| At least 1 | 1770 (25) | 1129 (91) | 2255 (85) |

Retirement at statutory age

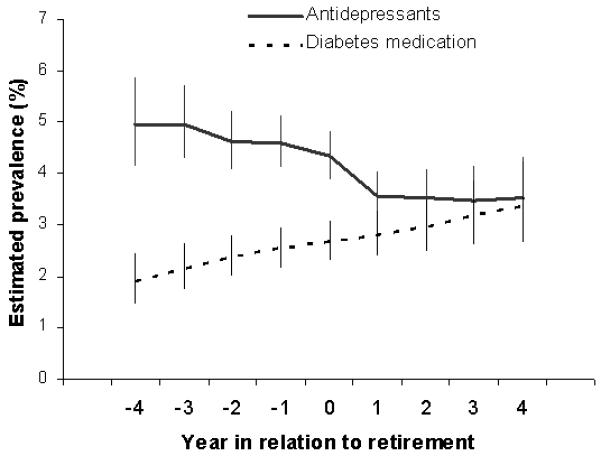

Figure 1 displays the estimated annual prevalence of antidepressant and diabetes medication use in relation to statutory retirement, adjusted for retirement age and calendar year. As demonstrated by unadjusted prevalences (eFigures 1 and 2, http://links.lww.com), the patterns were not driven by the effect of calendar time. Among old-age retirees, there was a 23% decline in the level of antidepressant use following the transition to retirement. The corresponding prevalence ratio for antidepressant use 1 year after vs. 1 year before retirement, adjusted for retirement age and calendar year, was 0.77 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.88). In contrast, there was no substantive change in antidepressant use during the pre-retirement period (0.93 [0.81 to 1.06]) or during the post-retirement period (1.00 [0.88 to 1.14]). We found little evidence to suggest that pre-retirement factors confounded the observed trajectories, as the results from multivariate adjusted models largely replicated the main findings.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of antidepressant and diabetes medication use adjusted for calendar year and retirement age, in relation to year of retirement at statutory age (error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals). Note that the figure is corrected for the increasing secular trend in prescriptions during the study period.

Antidepressant use decreased during the transition period in both sexes. During the post-retirement period, the use increased in men but not women (eTable2, http://links.lww.com). Socioeconomic status and the presence of previous sickness absence periods also modified the antidepressant trajectory. After adjusting for retirement age and calendar year, antidepressant use decreased by 32% during the retirement transition period among employees in the highest socioeconomic status group, and less for other socioeconomic groups (15% to 16%). The decrease in antidepressant use during the transition to retirement was stronger among statutory retirees who had long-term sickness absence periods during the transition period (adjusted prevalence ratio = 0.65 [CI = 0.55 to 0.77]) than among those with no history of disabling diseases (0.94 [0.80 to 1.11]). Thus, statutory retirement appeared to be particularly beneficial for those with pre-existing health problems at work.

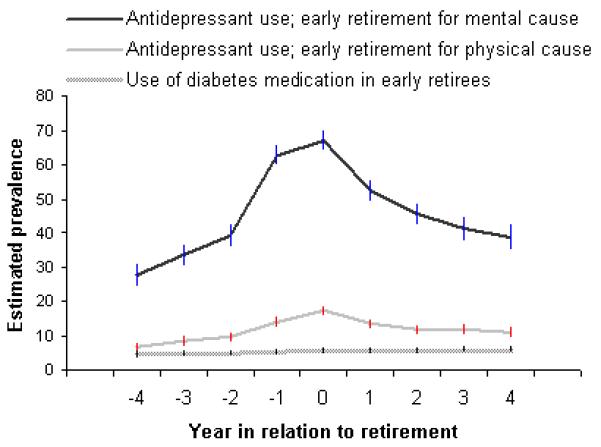

Early retirement on health grounds

As shown in Figure 2, a different pattern of antidepressant use trajectories was observed for retirement due to poor health. The shape of the antidepressant trajectory did not depend on calendar time (eFigures 3 and 4, http://links.lww.com) but varied by the medical cause leading to early retirement. Among persons who retired due to mental disorders, antidepressant use increased during the pre-retirement period (adjusted risk ratio= 1.42 [95% CI = 1.28 to 1.57]), peaking in the year of retirement, and decreasing post retirement (Table 3). Again, the association was dependent on socioeconomic status. Persons in the highest socioeconomic group decreased their antidepressant use after retirement more than other socioeconomic groups (eTable 3, http://links.lww.com).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of antidepressant use in relation to year of early retirement due to mental causes and physical causes separately and prevalence of use of drugs for diabetes in both these cohorts combined, adjusted for retirement age and calendar year. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Note that the figure is corrected for the increasing secular trend in prescriptions during the study period. (Notice that the scale for y-axis is different than in Figure 1.)

Table 3.

Trends in antidepressant use within the transition period and the pre- and post-retirement periods by type and main cause of retirementa

| Antidepressant use | Pre-retirement period (years −4 to −2) |

Transition period (years −1 to +1) |

Post-retirement period (years +2 to +4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statutory retirees | |||

| Prevalence difference (95% CI), % | −0.2 (−0.7 to 0.3) | −0.9 (−1.5 to −0.4) | 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.7) |

| Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | 0.93 (0.81 to 1.06) | 0.77 (0.68 to 0.88) | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.14) |

| Early retirees, mental causes | |||

| Prevalence difference (95% CI), % | 10.2 (7.0 to 13.4) | −9.1 (−12.5 to −5.8) | −8.7 (−11.5 to −5.8) |

| Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | 1.42 (1.28 to 1.57) | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.93) | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.90) |

| Early retirees, physical causes | |||

| Prevalence difference (95% CI), % | 2.8 (1.5 to 4.2) | −0.5 (−2.0 to 1.0) | −1.1 (−2.3 to 0.2) |

| Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | 1.45 (1.22 to 1.71) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.06) | 0.92 (0.83 to 1.02) |

All figures are adjusted for retirement age and calendar year.

We found a simpler antidepressant trajectory among those retiring due to physical health issues (Figure 2). As shown in Table 3, there was an increasing trend in antidepressant use during the pre-retirement period (prevalence ratio = 1.45 [95% CI = 1.22 to 1.71]), but little change in trend in antidepressant use within the retirement transition period or the post-retirement period. Apart from the area of residence, there were no differences in the change in trend between the periods by any background variable (eTable 4, http://links.lww.com).

We found no retirement-related changes in the trajectories of use of drugs for diabetes in any of the three groups (Figures 1 and 2). Instead, the estimated prevalence of annual diabetes medication use rose steadily with increasing age, (eFigure 2, http://links.lww.com) as would be expected for this age-related progressive disorder. Results from sensitivity analyses were consistent with the main analyses (eAppendix, http://links.lww.com).

DISCUSSION

In this large-scale study, objective repeated data on purchases of prescription medication were used as indicators of the potential effects of retirement on mental health. Data from serial measurements of antidepressant use during the retirement transition were consistent with the hypothesis that retirement may improve mental health among old-age retirees, as well as possibly also those retiring early on mental health grounds. After controlling for the rising secular trend in the prescription of antidepressants,22 the prevalence of antidepressant use decreased by one-fourth from before retirement to afterwards. The decrease in antidepressant use was greater among those who stayed employed until they were entitled to old-age pension despite health problems at work.

Retirement at statutory age

Our results are in agreement with those from the French GAZEL-cohort and the British Whitehall II study in which statutory retirement was associated with an improvement in self-rated mental health compared with staying employed.4,11,12,21 Several other studies based on self-report data have also provided evidence consistent with these observations.5-10

There are at least three possible explanations for these observations. First, release from the demands of work may be beneficial to mental health. This is supported by the observation that those who were encountering problems with disabling diseases benefited more than those without such conditions. Second, having more time to perform activities at home and elsewhere, could allow more autonomy to pursue own interests7 and more time to invest in health such as exercising.20 Increase in personal control8 could reduce need for antidepressant medication. Third, having worked until the age of receiving old age benefits may lead to feelings of having fulfilled society’s expectations.17

Alternative explanations should also be considered. For example, financial difficulties in retirement could decrease the likelihood of a depressed subject seeking medical advice, or lead to a reduction in the number of prescriptions filled by patients. However, the fact that the largest reduction in antidepressant use after retirement was seen in the highest socioeconomic status group suggests that filling fewer prescriptions after retirement is unlikely to be explained by financial concerns alone. A further explanation might be that the demands of work, including the need of medical certificates for longer sickness absences, could provide a stronger incentive for depressed subjects to see a doctor while still in work than in retirement. If the latter is the case, the decrease in purchases of antidepressants may not reflect a decrease of depression at retirement.

Retirement on health grounds

Although we observed a decrease in filled prescriptions, the level of antidepressant use remained high among those retiring due to mental health issues. This could reflect the chronic nature of depression and its high relapse rate33 and suggests that work was not the primary cause of depression. As the prevalence of antidepressant use increased leading up to retirement and decreased after transition to retirement, our findings may also be affected by the effort expended to retain the ability to work. A further potential explanation is that anticipation and decision-making in the years before retirement can be stressful, reflected by an increased antidepressant use before retirement. Without further research using other indicators of mental health, it may not be possible to determine whether the observed decline in antidepressant use after retirement was driven by a true improvement in mental health or by the cessation of unsuccessful treatment efforts to continue work.

Those retiring due to physical health issues did not reduce their antidepressant use, which is consistent with previous studies using other health indicators.14, 19 The explanation for the observed consistency in the prevalence of antidepressant use in pre- and post-retirement could be that retirement did not alter the course of the physical illness leading to early retirement but, instead, pain and low level of physical activity causing poor sleep and poor mental health continued to prevail at the same level.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the study include the large sample size and serial measurements of antidepressant use across a 9-year period centered around retirement and based on comprehensive prescription records obtained from national registers. However, there was some variation in sample size during the first three years and the last three years of the 9-year observation window. This was because of the limited follow-up for participants who retired at either end of the fixed observation window and for those who died during the follow-up. Nevertheless, selective sample retention is unlikely to explain our findings because the results from sensitivity analyses restricting the sample to those who had complete data at all years of the pre-retirement and transition periods were consistent with the main results.

The use of antidepressant data circumvented potential response bias from self-reported questionnaires. The validity of our finding was also strengthened by the specificity of the association between retirement and antidepressant use. The purchases of diabetes medication were not altered by retirement (as hypothesized), but, instead, increased over time with increasing age and calendar year, as expected.34, 35 Furthermore, our results of a higher prevalence of antidepressant users among women compared with men correspond to sex differences in the prevalence of depression reported for general populations.36

Some caveats should be noted with respect to the data on antidepressants. Filling a prescription does not equate to the actual use of medication, and prescriptions do not capture undiagnosed disease or conditions treated without medication. Thus, using antidepressant prescriptions as a proxy for mental health may have captured only the “tip of the iceberg” of common mental health problems.8 Furthermore, some misclassification is possible because these medications are also used to treat other mental disorders, such as eating or sleeping disorders, and chronic pain. We consider this error to be small because patients with depression and anxiety represent a vast majority of those taking antidepressants.37 We may also have misclassified depressed employees who were treated with atypical antipsychotics, although they are typically used in combination with antidepressants when treating depression with psychotic features. Because we did not have information on the planned duration or recommended dose of the antidepressant treatment, we could not use more fine-grained measures such as discontinuation of antidepressant use.

Conclusion

The observed trajectories of recorded purchases of antidepressant medication are consistent with the hypothesis that retirement may be beneficial for mental health. Future research should investigate the generalizability of the findings to other countries and settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by the National Institute on Aging, NIH, US (R01AG034454), the BUPA Foundation, UK, EU New OSH ERA research programme, the participating organisations, and the Academy of Finland (grants #124271, #124322, #126602, #129262 and #132944).

Footnotes

SDC Supplemental digital content is available through direct URL citations in the HTML and PDF versions of this article (www.epidem.com).

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.OECD . Live longer, work longer. OECD Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD Ageing and pension system reform: implications for financial markets and economic policies. 2005.

- 3.WHO . Gaining health. The European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. WHO Regional Committee for Europe; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westerlund H, Vahtera J, Ferrie JE, et al. Effect of retirement on major chronic conditions and fatigue: French GAZEL occupational cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c6149. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mein G, Martikainen P, Hemingway H, Stansfeld S, Marmot M. Is retirement good or bad for mental and physical health functioning? Whitehall II longitudinal study of civil servants. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:46–49. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salokangas R, Joukamaa M. Physical and mental health changes in retirement age. Psychother Psychosom. 1991;55:100–107. doi: 10.1159/000288415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mojon-Azzi S, Sousa-Poza A, Widmer R. The effect of retirement on health: a panel analysis using data from the Swiss Household Panel. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137:581–585. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drentea P. Retirement and Mental Health. J Aging Health. 2002 May 1;14:167–194. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400201. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gall TL, Evans DR, J H. The retirement adjustment process: changes in the well-being of male retirees across time. Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52:110–117. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.3.p110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reitzes D, Mutran E, Fernandez M. Does retirement hurt well-being? Factors influencing self-esteem and depression among retirees and workers. Gerontologist. 1996;36:649–656. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jokela M, Ferrie JE, Gimeno D, et al. From Midlife to Early Old Age: Health Trajectories Associated With Retirement. Epidemiology. 2010;21:284–290. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d61f53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vahtera J, Westerlund H, Hall M, et al. Effect of retirement on sleep disturbances: the GAZEL Prospective Cohort Study. Sleep. 2009;32:1459–1466. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.11.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossé R, Aldwin CM, Levenson MR, Ekerdt DJ. Mental health differences among retirees and workers: Findings from the normative aging study. Psychol Aging. 1987;2:383–389. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.2.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buxton J, Singleton N, Melzer D. The mental health of early retirees: National interview survey in Britain. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0866-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alavinia S, Burdorf A. Unemployment and retirement and ill-health: a cross-sectional analysis across European countries. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;82:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s00420-008-0304-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill S, Butterworth P, Rodgers B, Anstey K, Villamil E, Melzer D. Mental health and the timing of Men’s retirement. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiology. 2006;41:515–522. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villamil E, Huppert F, Melzer D. Low prevalence of depression and anxiety is linked to statutory retirement ages rather than personal work exit: a national survey. Psychol Med. 2006;36:999–1009. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butterworth P, Gill SC, Rodgers B, Anstey KJ, Villamil E, Melzer D. Retirement and mental health: Analysis of the Australian national survey of mental health and well-being. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1179–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melzer D, Buxton J, Villamil E. Decline in common mental disorder prevalence in men during the sixth decade of life. Soci Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:33–38. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0704-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Midanik L, Soghikian K, Ransom L, Tekawa I. The effect of retirement on mental health and health behaviors: the Kaiser Permanente Retirement Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50B:59–61. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.1.s59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westerlund H, Kivimäki M, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Self-rated health before and after retirement in France (GAZEL): a cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1889–1896. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore M, Yuen HM, Dunn N, Mullee MA, Maskell J, Kendrick T. Explaining the rise in antidepressant prescribing: a descriptive study using the general practice research database. BMJ. 2009;339:b3999. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Social Insurance Institution of Finland [Accessed January 3, 2011];Overview of Benefit Programmes. http://www.kela.fi.

- 24.Hietaniemi M, Ritola S. The Finnish Pension system. Vol 6. Gummerus Kirjapaino; Helsinki, Finland: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.OECD . Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers. OECD Publishing; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sjösten N, Vahtera J, Salo P, et al. Increased risk of lost workdays prior to the diagnosis of sleep apnea. Chest. 2009;136:130–136. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suoyrjö H, Oksanen T, Hinkka K, et al. The effectiveness of vocationally oriented multidisciplinary intervention on sickness absence and early retirement among employees at risk: an observational study. Occup Environ Med. 2009 April;66:235–242. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.038067. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.StatisticsFinland . Classification of occupations. Statistics Finland; Helsinki: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipsitz S, Kim K, Zhao L. Analysis of repeated categorical data using generalized estimating equations. Stat Med. 1994;13:1149–1163. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moen P. A life course perspective on retirement, gender, and well-being. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1:131–144. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.1.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim J, Moen P. Retirement transitions, gender, and psychological well-being: a life-course, ecological model. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:212–222. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.p212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS Calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King M, Nazareth I, Levy G, et al. Prevalence of common mental disorders in general practice attendees across Europe. Br J Psychiatry. 2008 May 1;192:362–367. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039966. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King D, Ellis T, Everett C, Mainous AI. Medication use for diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia from 1988–1994 to 2001–2006. South Med J. 2009;102:1127–1132. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181bc74c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tabák AG, Jokela M, Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M, Witte DR. Trajectories of glycaemia, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 2009;373:2215–2221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60619-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder. JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mark TL. For what diagnoses are psychotropic medications being prescribed?: A nationally representative survey of physicians. CNS Drugs. 2010;24:319–326. doi: 10.2165/11533120-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.