Abstract

Objective.

This study attempts to explain the ubiquitous positive correlation between cognitive ability (IQ) and survival.

Methods.

A sample of 10,317 Wisconsin high school graduates of 1957 was followed until 2009, from ages 18 to 68 years. Mortality was analyzed using a Weibull survival model that includes gender, social background, Henmon–Nelson IQ, and rank in high school class.

Results.

Rank in high school class, a cumulative measure of responsible performance during high school, entirely mediates the relationship between adolescent IQ and survival. Its effect on survival is 3 times greater than that of IQ, and it accounts for about 10% of the female advantage in survival.

Discussion.

Cognitive functioning may improve survival by promoting responsible and timely patterns of behavior that are firmly in place by late adolescence. Prior research suggests that conscientiousness, one of the “Big Five” personality characteristics, plays a key role in this relationship.

Keywords: Cognition, Death and dying, Gender, Health risk behaviors, Intellectual functioning, Life events and contexts, Longevity, Personality, Risk perception, Successful aging

RESEARCH on the association between early IQ and survival has led to the development of a nascent subdiscipline cognitive epidemiology (Deary & Batty, 2006, 2007; Deary, 2009, 2010; Deary, Whalley, & Starr, 2009; Lubinski, 2009). Much of this research has been integrated in a comprehensive account of follow-ups to the Scottish Mental Surveys (Deary et al., 2009). In addition to overall mortality (Batty, Wennerstad, et al., 2009; Hart, Deary, et al., 2003; Hart, Taylor, et al. 2003; Hart et al., 2005; Leon, Lawlor, Clark, Batty, & Macintyre, 2009; Osler et al., 2003; Whalley & Deary, 2001), IQ has been associated with accidental deaths (Batty, Deary, Schoon, & Gale, 2007; Batty, Gale, Tynelius, Deary, & Rasmussen, 2009; O’Toole, 1990; O’Toole & Stankov, 1992; Young, 2008), with homicide (Batty, Deary, Tengstrom, & Rasmussen, 2008), with hypertension, stroke, and cardiovascular disease (Batty, Mortensen, Andersen, & Osler, 2005; Batty, Modig Wennerstad, et al., 2007; Hart, Taylor, Davey, et al., 2003; Lindgarde, Furu, & Ljung, 1987; Starr et al., 2004), with quitting smoking (Taylor et al., 2003), and with time to menopause (Kuh et al., 2005; Richards, Kuh, Hardy, & Wadsworth, 1999; Shinberg, 1998; Whalley, Fox, Starr, & Deary 2004).

These studies provide little evidence that differential survival by IQ is explained by the well-established correlation of IQ with social and economic origins. There is mixed evidence that the effects of IQ on mortality are mediated by one's own education and socioeconomic success (Batty, Wennerstad, et al., 2009; Link & Phelan, 2005; Link, Phelan, Miech, & Westin, 2008). In this article, we analyze the association between adolescent IQ and survival from ages 18 to 69 in a large American sample of high school graduates. The IQ–survival association is entirely explained by a cumulative measure of academic performance (rank in high school class) that is only moderately associated (r = .6) with IQ, leaving almost two thirds of its variance unexplained. Moreover, the effect of rank in high school class on survival is about three times larger than that of IQ. This finding suggests that higher cognitive functioning improves the chances of survival because it leads to behaviors that are responsible, well organized, timely, and appropriate to the situation and that such patterns of behavior are well established by late adolescence. Prior research suggests that conscientiousness, one of the “Big Five” personality characteristics, plays a key role in this relationship. It is a well-established antecedent of academic performance in high school (Poropat, 2009), and it is also related to health and survival at older ages (Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg 2007).

Deary's (2008) essay in Nature noted that an association between “early life intelligence and mortality” has been established “across different populations, in different countries, and in different epochs.” He offered four potential explanations of this ubiquitous finding: higher education, healthy behaviors, early insults to the brain, and system integrity: “First, … intelligence is associated with more education and thereafter with more professional occupations that might place the person in healthier environments. … Second, people with higher intelligence might engage in more healthy behaviours. … Third, mental test scores from early life might act as a record of insults to the brain that have occurred before that date. … Fourth, mental test scores obtained in youth might be an indicator of a well-put-together system. It is hypothesized that a well-wired body is more able to respond effectively to environmental insults” (p. 176). The first two and the last two of these potential mechanisms differ in one important respect. Education and health behaviors are mediating mechanisms, although Deary's text suggests that IQ may be a proxy measure of “insults to the brain” and “a well-wired body.” The present analysis focuses on another mechanism that may mediate the life-long influence of intelligence.

Importantly, Deary's essay also referred to a finding that “being more dependable or conscientious in childhood is also significantly protective to health” (Deary, Batty, Pattie, & Gale, 2008; Schwartz et al., 1995), yet this may be the key to explaining the association between IQ and survival. Some of the risk factors that account for health differentials, for example, smoking, drinking, overeating, and lack of exercise, are known by almost all adults. The important question is not whether these risks are known and understood, but why people continue to ignore them.

Some researchers have emphasized strictly cognitive explanations for the association between survival and IQ early in life. In a prize-winning article, Gottfredson (2004) has suggested that IQ is “the epidemiologists’ elusive fundamental cause of social class differences in health,” thus implying that it may account for the influence of socioeconomic standing on survival. Deary has written “Whether you live to collect your old-age pension depends in part on your IQ at age 11. You just can’t keep a good predictor down” (Deary, 2005). Batty and Deary (2004) interpret the IQ differential as attributable to excessive cognitive demands in health care settings: “Given their inherently complex and sometimes conflicting nature, health care messages, treatment regimens, and preventative strategies perhaps surpass the cognitive abilities of some people. If this is the case—and bearing in mind that oversimplification of advice might reduce effectiveness substantially—proactive involvement of health care providers is warranted to reduce health inequalities attributable to differences in cognitive ability.” Although cognitive limits may well affect understanding and compliance in health care settings, there is no direct evidence that this accounts for the association between survival and IQ in early life.

Moreover, the recent literature on IQ and survival may have overemphasized the implications of findings that identify variables(s) as statistically significant predictor(s) of mortality. Estimates of relative hazard or odds ratios and their standard errors may have very weak practical implications, despite their statistical reliability.

For example, consider the recent article in which Batty, Wennerstad, and colleagues (2009) estimated the relationship between IQ (military induction test) and mortality among 1 million Swedish men for ∼20 years (from roughly age 18 to 38 years). Their main finding is a highly significant hazard ratio of 1.32 for the association between a 1 SD difference in IQ and the likelihood of death. Although this effect appears to be large, it has almost no impact on expected years of life within the age span covered by the survey (roughly 20 years). Of the 968,846 men in the Swedish cohort, just 14,498 men died. At the ages in question, the overall hazard is small and virtually constant, so it is fair to approximate the hazard as 14,498/(20 X [times au] 968,846) = .0007482. This implies about19.85 years of expected life, that is, just 0.15 years below the maximum of 20. If average IQ in the cohort was a full standard deviation higher—a most unlikely event—the hazard would fall to .0005668, and the expected number of years of life would rise to 19.89 years, just 0.04 years higher than before. To be sure, under this assumption, the number of deaths would fall by 24% but that merely underscores the extremity of assuming a 1 SD rise in average IQ.

Existing research on IQ and survival leaves many important questions unanswered. Is the association between IQ and survival a consequence of purely cognitive processes? Or are there other intervening mechanisms? If IQ were immutable, which is increasingly doubtful (Nisbett, 2009), what avenues of intervention are available? What good would it do to intervene in the medical care setting if the influence of cognition is pervasive across the life course? Is cognition about health issues and medical procedures the real issue? And of what importance is the effect of IQ on survival, relative to other known correlates?

METHODS

The Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) has followed the lives of 10,317 Wisconsin high school graduates of 1957, a simple random sample of one third of their graduating class (Sewell, Hauser, Springer, & Hauser, 2004). The Wisconsin sample covered 70% to 75% of appropriately aged youth in Wisconsin (Sewell & Hauser, 1975). However, participants are all high school graduates and almost all non-Hispanic Whites, rather like two thirds of Americans of their birth cohorts. Because of the truncation of completed years of schooling, it is possible that effects both of IQ and of high school rank are attenuated in the WLS sample.

Gender was ascertained in a spring 1957 survey of the graduates. Cognitive ability (IQ) was measured in the junior year of high school (1956) using the Henmon–Nelson test of mental ability. The Henmon–Nelson test is a group-administered, 30-min, multiple choice assessment that consists of 90 verbal or quantitative items. It was administered in all Wisconsin high schools at various grade levels from the 1930s through the 1960s as part of a cooperative effort of high schools and colleges to identify youth who might succeed in college but did not originally plan to attend college (Henmon & Holt, 1931; Henmon & Nelson, 1946, 1954).

Rank in high school class was ascertained directly from high school records. In U.S. high schools, rank in class is based on the mean grade assigned in courses taken throughout the high school career. Although it appears in WLS survey records as an ordinal variable, one might expect that, because of the large number of course grades that it reflects, the distribution of grade point average is itself approximately normal. In some parts of the analysis, we have followed the convention of cognitive psychology by comparing survival between the highest and lowest shares of the distribution of IQ and of high school rank. Thus, the analysis permits nonlinearities in the effects of those variables. At a few points, we have normalized the distributions of each variable by choosing ordinates of the normal distribution corresponding to rank positions, thus creating a standardized common metric in which the variables are approximately normally distributed.

Parents’ incomes were obtained from federal income tax forms filed with the State of Wisconsin and averaged over the years 1957–1960, whereas parents’ occupations were ascertained from the tax forms or from surveys conducted in 1957 and 1975. In this analysis, IQ, high school rank, and parents’ income were each categorized in fifths of their distribution, and family head's occupation was classified as either farm or nonfarm. Several other social background variables were measured in the WLS, including parents’ educational attainments, occupational status, intact family, and number of siblings (Sewell et al., 2004). These variables were not directly associated with survival, and, thus, they cannot account for the association between IQ and survival. For that reason, they were dropped from the analysis.

Years of death from 1957 through 2008 were obtained from the Social Security Death Index, from vital records of the State of Wisconsin, or from survivors of decedents. Of the 10,317 members of the sample, 1,603 had died by the end of 2008, and 8,701 were known to have survived. Exact dates of death were unknown for 50 decedents. Of these, 20 were known to have died between 1957 and 1964, 22 between 1964 and 1975, and 8 between 1957 and 1975. Mortality status was unknown in only 13 cases, and those were excluded from the analysis.

In fewer than 7% of cases, data on high school rank, parents’ incomes, or parents’ occupations were multiply imputed following the procedure suggested by Van Buuren, Boshuizen, and Knook (1999) and implemented by Royston (2004, 2005, 2007) in the imputation with chained equations routine in Stata 10. Conditional on each of five such imputations, missing years of death between 1957 and 1975 were multiply imputed five times for the 50 cases mentioned previously, assuming a Weibull distribution. Analyses of survival were estimated in Stata 10 assuming a Weibull distribution for each of the 25 fully imputed sets of data. In this large sample, we found that adjustment of standard errors for the effect of imputation were negligible, so we have reported estimates from a single imputation. Imputation and estimation was also carried out assuming a Gompertz distribution, confirming the findings reported here.

The workhorse of our analyses is a parametric survival model defined on the age interval (18,68). Although our analysis obviously ignores mortality in childhood, adolescence, and late life, it covers a longer span of the life course than all but one sample that has previously been studied, that is, the sample based on the Scottish Mental Survey of 11-year-olds in1932 (Deary, Whalley, & Starr, 2003; Deary, Whiteman, Starr, Whalley, & Fox, 2004; Deary et al., 2009). Individuals whose survival was not ascertained (N = 13) or who survived to 2009 (N = 8,701) were censored. The model is as follows:

| (1) |

where μ(x) is the force of mortality evaluated at exact age x, μ0 is a baseline force of mortality evaluated at age x, β is a vector of parameters, and X is a vector of covariates. For pragmatic reasons, we choose a Weibull hazard to represent the baseline μ0 (x) thus imposing the following parametric form:

| (2) |

where γ is a level parameter and ρ is the shape parameter. It is well known that a Weibull hazard can be parameterized as a Gompertz hazard defined on the log of duration (rather than on duration). Both functions capture the pattern of mortality well from adolescence to late adulthood though the Weibull function rises too slowly at ages above 75 to represent mortality well above those ages. However, because the Gompertz and Weibull perform equally well below ages 75 and because a Weibull parametric hazard is also an accelerated failure time model (and hence more robust to some violations of the proportionality assumption), we chose to present results using the Weibull parameterization.

In addition to estimating the vector of parameters, β, along with ρ and γ (shown in Table 1), we calculated the predicted integrated hazard, I(y; β, ρ, γ), for selected subgroups (setting all the variables not defining the subgroups to their sample means), shown in Figures 2 and 3, the probabilities of surviving S(x; β, ρ, γ) = exp(−I(y; β, ρ, γ), shown in Table 2, and finally, the expected duration in the intervals (x, 68) for all x between 18 and 67. The expected durations are displayed relative to the maximum possible remaining years of life in Figure 5. The latter three quantities are more interpretable measures of the ultimate effects of selected covariates than the vector, β, or the relative hazards, exp(β).

Table 1.

Estimated Parameters of Weibull Models: Survival of Wisconsin High School Graduates from 1957 to 2008

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| Constant | −11.437 (0.240) | −11.244 (0.245) | −11.105 (0.247) |

| Shape | 0.879 (0.025) | 0.879 (0.025) | 0.880 (0.025) |

| Male | 0.479 (0.051) | 0.482 (0.051) | 0.410 (0.053) |

| Medium low IQ | −0.141 (0.075) | −0.136 (0.075) | −0.058 (0.077) |

| Medium IQ | −0.061 (0.074) | −0.049 (0.074) | 0.070 (0.079) |

| Medium high IQ | −0.213 (0.079) | −0.195 (0.079) | −0.026 (0.087) |

| High IQ | −0.216 (0.080) | −0.188 (0.081) | 0.069 (0.097) |

| Farm background | −0.204 (0.070) | −0.183 (0.071) | |

| Medium low parents’ income | −0.211 (0.078) | −0.205 (0.078) | |

| Medium parents’ income | −0.140 (0.079) | −0.133 (0.079) | |

| Medium high parents’ income | −0.220 (0.081) | −0.221 (0.081) | |

| High parents’ income | −0.319 (0.084) | −0.312 (0.084) | |

| Medium low rank in high school class | −0.201 (0.075) | ||

| Medium rank in high school class | −0.301 (0.079) | ||

| Medium high rank in high school class | −0.249 (0.084) | ||

| High rank in high school class | −0.513 (0.100) |

Note: Parenthetic entries are approximate standard errors.

Figure 2.

Nelson–Aalen cumulative hazard estimates by IQ.

Figure 3.

Nelson–Aalen cumulative hazard estimates by class rank.

Table 2.

Expected Years of Life from 1957 to 2008 by Gender, IQ, Farm Origin, Parents’ Income, and Rank in High School Class: Wisconsin Longitudinal Study

| Variables in Weibull model | Men | Women | Low IQ | High IQ | Farm | Nonfarm | Low income | High income | Low rank | High rank |

| Model 1: gender and IQ | 50.5 | 51.8 | 50.9 | 51.5 | ||||||

| Model 2: gender, IQ, farm origin, parents’ income | 50.5 | 51.8 | 50.9 | 51.4 | 51.6 | 51.1 | 50.7 | 51.6 | ||

| Model 3: gender, IQ, farm origin, parents’ income, rank in high school class | 50.7 | 51.7 | 51.3 | 51.1 | 51.6 | 51.2 | 50.8 | 51.6 | 50.5 | 51.9 |

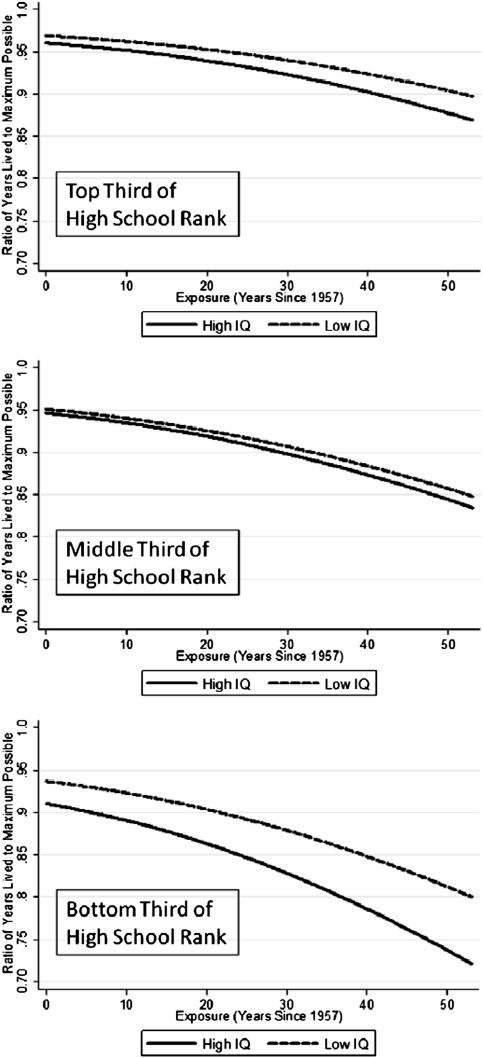

Figure 5.

Ratio of years lived to the maximum possible by high school rank among the extreme fifths in IQ: Weibull model with gender, IQ, family background, and high school rank.

Our estimation strategy consisted of building successively more complicated models while paying close attention to the role of common causes and mediating mechanisms. The model of relations we have in mind is shown in Figure 1. Our main conjecture is that the effects of IQ are mediated by variables that could be correlated with it but that also represent traits quite different from intellectual skills and are more suitably thought of as indicators of character and personality as well as by behaviors during adulthood (Deary et al., 2008). The model in Figure 1 includes constructs whose indicators are not included in our analysis, for example, personality characteristics and variables representing early childhood environments and events that may have shaped or constrained IQ. The estimated effect of IQ will overstate its true effect if early childhood conditions that have been left out of our analysis have independent effects on IQ and on mortality (Barker, 2001; Nisbett, 2009; Palloni, 2006).

Figure 1.

Relations between factors producing mortality risks at adult ages.

RESULTS

Figures 2 and 3 describe observed mortality differentials by IQ and high school rank. Figure 2 shows Nelson–Aalen cumulative hazard estimates of mortality among the top and bottom fifths of Wisconsin graduates in IQ. The two groups have very similar cumulative mortality through the first 20 years after graduation, but life chances diverge modestly thereafter. On the same scale, Figure 3 shows corresponding estimates of the cumulative hazard of mortality for the top and bottom fifths in high school rank. Here, the mortality experience of the two groups diverges within 10 years of graduation, and by 2008, the cumulative risk of death is nearly twice as large among the lowest as among the highest ranking students. Plainly, although there is differential mortality by IQ in the Wisconsin cohort, the differential by high school rank is far larger. In fact, when linear models are estimated with Henmon–Nelson IQ and high school rank in a common metric—a transformation of rank position on each variable into unit normal deviates—the effect of high school rank is three times larger than that of IQ.

Table 1 shows estimated parameters of Weibull models of survival in the Wisconsin cohort. Model 1 includes only a dummy variable for gender and dummy variables for fifths of the IQ distribution. As one should expect, men experience much higher mortality than women, whereas mortality decreases as IQ increases. The odds of mortality are almost 20% lower in the top fifth of IQ than in the bottom fifth. Model 2 adds social background variables to the model. Graduates with farm background have a mortality advantage that is roughly as large as that of the top fifth in IQ relative to the bottom fifth, whereas the differential in mortality by parents’ income is substantially larger than that by IQ. We suspect, but cannot demonstrate, that farm children have a survival advantage, either by dint of their early life experience in the rural context or, possibly, because of adverse selection in the early years of life. It is unlikely that there was a persisting favorable effect of rural location for very few members of the cohort remained in rural areas in adulthood.

The odds of mortality among the top fifth of graduates in parents’ income are more than 25% less than among the bottom fifth. The effect of IQ barely changes when the social background variables are added to the model, so the association between IQ and survival is not an artifact of its association with social background characteristics that affect survival.

In Model 3, high school rank is added; its effects are large and statistically significant. The odds of mortality are more than 40% lower in the top fifth of the class than in the bottom fifth; the obverse is that the odds of mortality are two thirds greater in the bottom than in the top fifth. The inclusion of high school rank in Model 3 scarcely alters the effects of the social background variables, but it has marked effects on the estimated coefficients of gender and of IQ. In Model 2, the odds of mortality among men are 62% greater than among women, but in Model 3, the gender differential is reduced to 51%. The reason is that high school girls earn higher grades than high school boys of equal IQ—by nearly half a standard deviation—and that accounts in part for the gender differential in mortality. Duckworth and Seligman (2005, 2006) have shown that self-discipline—an aspect of conscientiousness—has a large effect on high school grades and explains the female advantage.

More important, once high school rank enters the model, there are no longer any statistically significant differentials in mortality by IQ. That is, the association between IQ and mortality is entirely explained by its correlation—presumably a causal relationship—with high school rank. However, that correlation is far from perfect. Among the Wisconsin graduates, the correlation is r = .6, which is to say that nearly two thirds of the variance in high school rank is independent of IQ. Figure 4 displays a scatter-plot of the relationship between Henmon–Nelson IQ and class rank. Plainly, there is a great deal of variability in class rank among individuals with the same IQ. To be sure, this is due in part to the fact that average IQ varies among high schools, although the distribution of class rank is necessarily the same in each school. However, <13% of the variance in IQ lies between schools and the within-school regression of rank on IQ—even after social background variables have been controlled—is virtually the same as the correlation reported here (Hauser, Sewell, & Alwin, 1976, pp. 323–324).

Figure 4.

Scatter-plot of rank in high school class by Henmon–Nelson IQ.

What is the difference between IQ and high school rank? IQ is based on a single test, administered late in the junior year of high school. It is a highly reliable, though imperfect measure. Based on the administration of the Henmon–Nelson test to 68% of the WLS sample (N = 7,001) during the freshman year of high school, its estimated test–retest reliability from the freshman to the junior years is .84 among women, among men, and in the total sample. This implies that that attenuation in the estimated effects of IQ on high school rank and on mortality is <10%, for .841/2 = .92. High school rank is operationally distinct from cognitive ability. It is a cumulative behavioral measure based on evaluations of performance on diverse academic tasks throughout 4 years of high school—assignment after assignment, test after test, teacher after teacher, and course after course. That is, it represents behaviors that are responsible, timely, consistent, and appropriate. The independent features of high school rank are behavioral, but also surely psychological in part, for they surely reflect character, habit, and personality. Personal characteristics, including, but also independent of cognitive ability, lead students to do the right thing in the right way at the right time and place when they are in secondary school; they evidently persist in ways that lead to greater longevity. Thus, the research question raised by the present finding is, “Beyond cognitive ability, what psychological characteristics lead both to successful academic performance and later health and survival?”

Table 2 shows selected estimates of expected years of life, based on the Weibull models, during the 52-year period of observation. In Models 1 and 2, women outlive men by 1.3 years, but in Model 3 women's advantage is reduced to 1 year. In Models 1 and 2, the highest fifth in IQ outlive the lowest fifth by about half a year, but that differential is actually eliminated in Model 3. Both in Model 2 and in Model 3, farm youth outlive nonfarm youth by about half a year, whereas high income youth outlive low income youth by almost a year. However, the largest differential in expected years of life is 1.4 years between youth in the top and bottom fifths of their high school classes.

To investigate the possibility that the effect of IQ varies across levels of high school rank, we estimated the Weibull model separately in the top, middle, and bottom thirds of the distribution of high school rank. These findings are summarized in Figure 5, which shows the effect of IQ on the ratio of expected years of life to the maximum possible years of life by years since 1957 in each third of the distribution of high school rank. For clarity, each panel of the figure shows only the ratios for the top and bottom fifths of the IQ distribution. If higher IQ had a salutary effect on survival, the curves for the top fifth in IQ would always be higher than the curves for the bottom fifth in IQ. However, an opposite pattern appears throughout the distribution of high school rank: Those with a very high IQ appear to be less likely to survive than those with a very low IQ. Although the graphics suggest a reversal of the effect of IQ within categories of high school rank, none of those estimates is statistically significant. Because each panel of Figure 5 is on the same vertical scale, a comparison among the panels clearly shows the positive effect of high school rank on survival. Moreover, although the graphics may suggest that the effects of IQ differ across the categories of high school rank, we have tested that hypothesis and found no significant interaction effects.

We also considered the possibility that effects of IQ and high school rank on survival might vary by age within the 52-year span of the present analysis. Thus, we estimated conditional logistic models of death at ages 18–36, 27–54, and 55–69 by gender. These confirmed the main findings of the analysis with a single exception that young men of farm origin were less likely than men of urban origin to survive in the immediate post-high school years. We suspect but cannot confirm that accidental deaths account for this reversal in the general pattern.

The WLS data do not permit a thorough analysis of the health-related behavioral consequences of IQ and high school rank. However, smoking behavior and binge drinking provide striking examples that may help to explain the relationship of IQ with mortality. In 1993, 54% of the Wisconsin graduates reported that they had smoked cigarettes at some time in their life. Among those who ever smoked, 67% reported that they had stopped, and they also reported the number of years that they had smoked. Almost 95% of the graduates reported that they had alcoholic beverages at some time in their life, but just 59% had any alcoholic beverages in the month preceding the interview. Those participants were asked the number of occasions on which they had consumed more than four alcoholic drinks in that month, and binge drinking was defined as the number of such occasions.

Table 3 reports regression analyses of smoking, quitting smoking, and binge drinking as reported in 1993. For convenience in interpretation, both Henmon–Nelson IQ and high school rank have been normalized and expressed in standard form, that is, with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.0. In Model 1, which includes only gender and IQ, the odds that a man ever smoked were 1.7 times as large as those of a woman, although IQ had no effect. Model 2 adds high school rank to the model. Here, the effect of IQ is statistically significant and positive, although increases in high school rank diminish the odds of smoking. That is, when high school rank is controlled, those with higher IQs were significantly more likely to smoke than those with lower IQs. The addition of high school rank to the model also explains about half the gender effect because men obtained lower grades in high school than women.

Table 3.

Regression Analyses of Health-Related Behaviors in 1993 by IQ, High School Rank, and Gender: Wisconsin Longitudinal Study

| Outcome variable | Male | Henmon–Nelson IQ | High school rank |

| Model 1. Ever smoked (odds ratio) | 1.695 (0.084) | 0.993 (0.025) | — |

| Model 2. Ever smoked (odds ratio) | 1.313 (0.071) | 1.363 (0.046) | 0.585 (0.021) |

| Model 3. Years smoked among quitters | 0.946 (0.397) | −0.827 (0.202) | — |

| Model 4. Years smoked among quitters | 0.164 (0.428) | 0.298 (0.260) | −1.967 (0.277) |

| Model 5. Binge-drinking occasions | 0.822 (0.064) | −0.125 (0.033) | — |

| Model 6. Binge-drinking occasions | 0.713 (0.070) | −0.024 (0.043) | −0.194 (0.044) |

Note: Henmon–Nelson IQ and high school rank are standardized with a mean of 0 and a SD of 1.

Models 3 and 4 pertain to the number of years of regular smoking among those who had ever smoked. In Model 3, which includes only gender and IQ, men smoked for about a year longer than women, although a 1 SD increase in IQ reduced the time to quitting by about 10 months. However, the addition of high school rank in Model 4 reduced the gender and IQ effects to nonsignificance and yielded the estimate that a 1 SD difference in high school rank reduced the time to quitting by almost 2 years.

Analyses of binge drinking—the number of times per month that an individual had more than four drinks on the same occasion—yield estimates that parallel those of smoking behavior. In Model 5, which includes only gender and IQ, the estimates suggest that men experience almost one more binge-drinking episode per month than women, whereas a 1 standard deviation shift in IQ reduces binge-drinking by about one eighth of an episode per month. Again, the introduction of high school rank in Model 6 reduces the IQ effect to statistical insignificance and partly explains the gender difference. In that model, a 1 SD increase in high school rank decreases binge drinking by one fifth of an episode per month.

Both in analyses of smoking behavior and of binge drinking, with just one exception, similar findings are obtained when the data for women and men are analyzed separately. In the case of women's binge drinking, IQ and high school rank have small and virtually equal negative effects. Also, there are other cases where effects on health outcomes or behaviors do not follow the same pattern as survival, smoking, and binge drinking. In the case of self-rated general health in 1993 (excellent or good vs. fair, poor, or very poor), both IQ and high school rank have small significant positive effects. The same holds in the case of participation in light exercise and participation in vigorous exercise. On the other hand, neither IQ nor high school rank affects the likelihood that a participant had a complete physical examination within the past year. Because the reports of health and health behaviors were first obtained when participants were 53–54-year old, we have not tried to investigate the degree to which any health-related behaviors mediate the influence of IQ and high school rank on mortality. Thus, much remains to be done before their effects on mortality will be fully understood.

DISCUSSION

Taken at face value, these findings suggest substantial modification in the previously offered explanations for the association between IQ and survival. There is no need to invoke “early insults to the brain” or “system integrity” to explain the association although such factors may well affect intelligence or they may affect high school rank in other ways. Neither is the effect of IQ necessarily mediated by postsecondary schooling—though some studies have found that the IQ–survival relationship is partly mediated by educational attainment (Link & Phelan, 2005; Link et al., 2008). The latter finding may be attributable to the fact that high school grades, more than test scores, account for the completion of college (Bowen, Chingos, & McPherson, 2009). Neither is it necessary to invoke health literacy, except to the extent that it may reflect highly motivated or compliant behavior—leaving aside the issue of cognitive decline among elderly individuals. The leading candidates to explain the IQ–survival relationship would appear to be lifelong attitudinal and behavioral patterns that contribute both to academic success in secondary school and to systematic accumulation of health benefits.

The present analysis cannot claim to parse the content of high school rank in terms of personality or motivation; no such measures were obtained in the baseline WLS survey of 1957. What does seem clear is that high school rank is a cumulative measure, both of intellectual ability and of responsible, compliant behavior, of consistently doing the right thing in the right way at the right time and place. Such behaviors are highly consistent with the definition of conscientiousness, which is one of the “Big Five” personality characteristics (Digman, 1989). For example, Roberts, Smith, Jackson, and Edmonds (2009) describe conscientiousness as “the propensity to be organized, controlled, industrious, responsible, and conventional.” This possibility has also been noted by Deary (2008): “For example, it seems that, independently of any association with intelligence, being more dependable or conscientious in childhood is also significantly protective to health.” Related findings have recently been reported elsewhere (Kern & Friedman, 2010; Roberts et al., 2007). That is, conscientiousness is both correlated with IQ and academic performance and implicated in later-life health and survival. Class rank in itself probably has little or no causal importance, and, to be sure, not everyone can be at the head of the class. The important things more likely are the personal characteristics, the habits, tendencies, and behaviors that lead to academic success. Conscientiousness would appear to be a key factor in this regard, and, ideally, the present analyses of longevity should be complemented in longitudinal data where IQ, conscientiousness, and high school grades have all been ascertained directly in early life.

Where educational attainment or other economic characteristics have been shown to mediate the association between IQ and survival, cognitive epidemiologists have sometimes argued that the mediating variables are merely proxies or surrogates for IQ. For example, Gottfredson (2004, p. 175) writes,

[S]uccessively better surrogates for g—income, occupation, education, health literacy—are successively stronger correlates of health outcomes. Analyses of the “job” of being a patient show that it requires the same cognitive skills that g represents and that most jobs require for good performance: efficient learning, reasoning, and problem solving. Both chronic diseases and accidents incubate, erupt, and do damage largely because of cognitive error, because both require many efforts to prevent what does not yet exist (disease or injury) and to limit damage not yet incurred (disability and death) if one is already ill or injured. Similar ideas have been expressed by Gottfredson and Deary (2004, p. 2) and Deary (2008, p. 176).

However, these statements do not hold up, if the supposed “proxies”—education, occupation, income, or, in the present case, high school rank—actually add to the explanation of survival (or health) by IQ. Figure 6 shows a causal model in which high school rank is only a proxy measure of IQ. In this scheme, high school rank is affected by social background, IQ, and gender, and by other, nonintellective causes that are uncorrelated with its observed causes. Mortality also depends on social background, IQ, gender, and other variables that are unrelated to its observed causes and to the nonintellective causes of high school rank. To the extent that high school rank is affected by IQ, one can properly call it a proxy or surrogate for IQ. However, in this model, high school rank itself has no independent influence on mortality. That is, the correlation of high school rank with mortality is entirely explained by their common dependence on social background, IQ, and gender.

Figure 6.

High school rank as a proxy or surrogate measure of IQ.

Figure 7 revises the model of Figure 6 to represent the findings of the present analysis. As shown in the diagram, there are three major changes in the scheme. First, as shown by Hauser, Tsai, and Sewell (1983), social background variables have no effect on high school rank net of IQ in the Wisconsin data. Second, as we have found, IQ no longer has any direct effect on mortality, and third, high school rank has a direct effect on mortality. That is, the effect of IQ on mortality is entirely mediated by high school rank. This occurs because there are additional nonintellective causes of high school rank that are not correlated with IQ, the sources of almost two thirds of the variance in high school rank and because the effect of high school rank is larger than that of IQ. The correlation between IQ and high school rank is just .60, so 64% (100 X [times au] (1 − .62)) of the variance in rank is independent of IQ; it is not merely a proxy measure of IQ. The effect of high school rank is about three times larger than that of IQ, and this can only occur because high school rank is largely caused by factors that are independent of IQ.

Figure 7.

A causal model of social background, gender, IQ, high school rank, and mortality.

To be sure, Figure 7 does not imply or suggest that IQ has no effect on mortality, but only that its effect is indirect, mediated by high school rank. To the extent that IQ is associated with survival, independent of social background, and other prior events and circumstances, its effects are real, and they are not at all diminished by the introduction of mediating variables. However, the present analysis ignores possible causal relationships between IQ and conscientiousness, as suggested by the unexplained correlation between IQ and personality traits in the hypothetical scheme of Figure 1. If greater intelligence breeds conscientiousness, then IQ remains a plausible cause and not merely a correlate of longevity. To the extent that there are other sources of correlation between IQ and conscientiousness, there would be reason to discount the causal significance of intelligence with respect to longevity. This is an important issue to address in future research.

The present analysis locates the explanation of the IQ–survival association firmly in patterns of behavior that are well established by late adolescence. However, it also raises many more questions than it answers. Are the present findings peculiar to the social circumstances of those who grew up in mid-20th century America? Do they hold in the many other studies in which the IQ–longevity relationship has been established? Among those studies, are there others in which the present findings can be tested? Is conscientiousness the key, behaviorally relevant characteristic of individuals that is reflected both in high school rank and in later survival? Are there others? Throughout life, what salutary behaviors are affected by them? And perhaps most important, how can those behaviors be altered, even in the absence of responsible habits in adolescence?

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG09775 and P01 AG21079 to R.M.H; R01 AG016209 and R37 AG025216 to A.P.); the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health (D43 TW001586 to A.P.); the William Vilas Estate Trust; and the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Computation was carried out using facilities of the Center for Demography and Ecology and the Center for Demography of Health and Aging at the University of Wisconsin-Madison with support from the National Center for Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health (R24 HD04783) and the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (P30 AG017266 to R.M.H.).

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors. A public-use version of WLS data is available from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research at the University of Michigan or the WLS Web site (http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/).

References

- Barker DJP. Fetal origins of cardiovascular and lung disease. New York, NY: M. Dekker; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Batty GD, Deary IJ. Early life intelligence and adult health. British Medical Journal. 2004;329:585–586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7466.585. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7466.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty GD, Deary IJ, Schoon I, Gale C. Childhood mental ability in relation to cause-specific accidents in adulthood: the 1970 British Cohort Study. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 2007;100:405–414. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm039. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcm039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty GD, Deary IJ, Tengstrom A, Rasmussen F. IQ in early adulthood and later risk of death by homicide: Cohort study of 1 million men. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;193:461. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037424. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty GD, Gale C, Tynelius P, Deary IJ, Rasmussen F. IQ in early adulthood, socioeconomic position, and unintentional injury mortality by middle age: A cohort study of more than 1 million Swedish men. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;169:606. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn381. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty GD, Modig Wennerstad K, Davey Smith G, Gunnell D, Deary IJ, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F. IQ in early adulthood and later cancer risk: Cohort study of one million Swedish men. Annals of Oncology. 2007;18:21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl473. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdl473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty GD, Mortensen E, Andersen A, Osler M. Childhood intelligence in relation to adult coronary heart disease and stroke risk: Evidence from a Danish birth cohort study. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2005;19:452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00671.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty GD, Wennerstad K, Smith G, Gunnell D, Deary I, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F. IQ in early adulthood and mortality by middle age: Cohort study of 1 million Swedish men. Epidemiology. 2009;20:100. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818ba076. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818ba076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WG, Chingos MM, McPherson MS. Crossing the finish line: Completing college at America's public universities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ. Intelligence, health and death. The Psychologist. 2005;18:610–613. doi:10.1038/456175a. [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ. Why do intelligent people live longer? Nature. 2008;456:175–176. doi: 10.1038/456175a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ. Introduction to the special issue on cognitive epidemiology. Intelligence. 2009;37: 517–519. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2009.05.001. [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ. Cognitive epidemiology: Its rise, its current issues, and its challenges. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;49: 337–343. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.11.012. [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ, Batty GD. Commentary: Pre-morbid IQ and later health—the rapidly evolving field of cognitive epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:670. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl053. doi:10.1016/j.surneu.2004.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ, Batty GD. Cognitive epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2007;61:378–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039206. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.039206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ, Batty GD, Pattie A, Gale C. More intelligent, more dependable children live longer: A 55-year longitudinal study of a representative sample of the Scottish nation. Psychological Science. 2008;19:874–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02171.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ, Whalley LJ, Starr JM. Brain and longevity: Perspectives in longevity. Berlin: Springer; 2003. IQ at age 11 and longevity: Results from a follow up of the Scottish Mental Survey 1932; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ, Whalley LJ, Starr JM. A lifetime of intelligence: Follow-up studies of the Scottish Mental Surveys of 1932 and 1947. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ, Whiteman M, Starr J, Whalley L, Fox H. The impact of childhood intelligence on later life: Following up the Scottish Mental Surveys of 1932 and 1947. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:130–147. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.130. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman J. Five robust trait dimensions: Development, stability, and utility. Journal of Personality. 1989;57:195–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00480.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth A, Seligman M. Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents. Psychological Science. 2005;16:939. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01641.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth A, Seligman M. Self-discipline gives girls the edge: Gender in self-discipline, grades, and achievement test scores. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:198–208. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.198. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson LS. Intelligence: Is it the epidemiologists’ elusive “fundamental cause” of social class inequalities in health? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:174–199. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.174. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson LS, Deary IJ. Intelligence predicts health and longevity, but why? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:1–4. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01301001.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hart C, Deary IJ, Taylor M, MacKinnon P, Davey Smith G, Whalley L. Starr J. The Scottish Mental Survey 1932 linked to the Midspan studies: A prospective investigation of childhood intelligence and future health. Public Health. 2003;117:187–195. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(02)00028-8. doi:10.1016/S0033-3506(02)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart C, Taylor M, Davey Smith G, Whalley L, Starr J, Hole D. Deary IJ. Childhood IQ, social class, deprivation, and their relationships with mortality and morbidity risk in later life: Prospective observational study linking the Scottish Mental Survey 1932 and the midspan studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:877–883. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088584.82822.86. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000088584.82822.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart C, Taylor M, Smith D, Whalley L, Starr J, Hole D, Deary IJ. Childhood IQ and all-cause mortality before and after age 65: Prospective observational study linking the Scottish mental survey 1932 and the Midspan studies. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10:153–165. doi: 10.1348/135910704X14591. doi:10.1348/135910704X14591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RM, Sewell WH, Alwin DF. High school effects on achievement. In: Sewell WH, Hauser RM, Featherman DL, editors. Schooling and achievement in American Society. New York: Academic Press; 1976. pp. 309–341. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RM, Tsai SL, Sewell WH. A model of stratification with response error in social and psychological variables. Sociology of Education. 1983;56(1):20–46. doi:10.2307/2112301. [Google Scholar]

- Henmon VAC, Holt FO. A report on the administration of scholastic aptitude tests to 34,000 high school seniors in Wisconsin in 1929 and 1930 prepared for the committee on cooperation, Wisconsin secondary schools and colleges. Madison, WI: Bureau of Guidance and Records of the University of Wisconsin; 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Henmon VAC, Nelson MJ. Henmon-Nelson tests of mental ability, high school examination—Grades 7 to 12-forms A, B, and C. Teacher's Manual. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin Company; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Henmon VAC, Nelson MJ. The Henmon-Nelson tests of mental ability. Manual for Administration. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin Company; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Kern ML, Friedman HS. Why do some people thrive while others succumb to disease and stagnation? Personality, social relations, and resilience. In: Fry PS, Keyes C, editors. New frontiers in resilient aging: Life-strengths and well-being in late life. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010. pp. 162–183. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511763151.008. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Butterworth S, Kok H, Richards M, Hardy R, Wadsworth M, Leon D. Childhood cognitive ability and age at menopause: Evidence from two cohort studies. Menopause. 2005;12:475. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000153889.40119.4C. doi:10.1097/01.GME.0000153889.40119.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon D, Lawlor D, Clark H, Batty GD, Macintyre S. The association of childhood intelligence with mortality risk from adolescence to middle age: Findings from the Aberdeen Children of the 1950s cohort study. Intelligence. 2009;37:520–528. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2008.11.004. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgarde F, Furu M, Ljung B. A longitudinal study on the significance of environmental and individual factors associated with the development of essential hypertension. British Medical Journal. 1987;41:220–226. doi: 10.1136/jech.41.3.220. doi:10.1136/jech.41.3.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B, Phelan J. Fundamental sources of health inequalities. In: Mechanic D, Rogut LB, Colby DC, Knickman JR, editors. Policy challenges in modern health care. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Link B, Phelan J, Miech R, Westin E. The resources that matter: Fundamental social causes of health disparities and the challenge of intelligence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49:72–91. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900106. doi:10.1177/002214650804900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubinski D. Cognitive epidemiology: With emphasis on untangling cognitive ability and socioeconomic status. Intelligence. 2009;37:625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2009.09.001. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE. Intelligence and how to get it: Why schools and cultures count. 1st ed. New York: W. W. Norton; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole B. Intelligence and behaviour and motor vehicle accident mortality. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 1990;22:211–221. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(90)90013-b. doi:10.1016/0001-4575(90)90013-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole B, Stankov L. Ultimate validity of psychological tests. Personality and Individual Differences. 1992;13:699–716. [Google Scholar]

- Osler M, Andersen A, Due P, Lund R, Damsgaard M, Holstein B. Socioeconomic position in early life, birth weight, childhood cognitive function, and adult mortality. A longitudinal study of Danish men born in 1953. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:681–686. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.9.681. doi:10.1136/jech.57.9.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A. Reproducing inequalities: Luck, wallets, and the enduring effects of childhood health. Demography. 2006;43:587–615. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0036. doi:10.1353/dem.2006.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poropat A. A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:322–338. doi: 10.1037/a0014996. doi:10.1037/a0014996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards M, Kuh D, Hardy R, Wadsworth M. Lifetime cognitive function and timing of the natural menopause. Neurology. 1999;53:308–314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B, Kuncel N, Shiner R, Caspi A, Goldberg L. The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2:313. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B, Smith J, Jackson J, Edmonds G. Compensatory conscientiousness and health in older couples. Psychological Science. 2009;20:553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02339.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal. 2004;4:227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: Update of ice. Stata Journal. 2005;5:527–536. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: Further update of ice, with an emphasis on interval censoring. Stata Journal. 2007;7:445–464. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J, Friedman H, Tucker J, Tomlinson-Keasey C, Wingard D, Criqui M. Sociodemographic and psychosocial factors in childhood as predictors of adult mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:1237–1245. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.9.1237. doi:10.2105/AJPH.85.9.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell WH, Hauser RM. Education, occupation, and earnings: Achievement in the early career. New York, NJ: Academic Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Sewell WH, Hauser RM, Springer KW, Hauser TS. As we age: The Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, 1957–2001. In: Leicht K, editor. Research in social stratification and mobility. Vol. 20. London: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 3–111. [Google Scholar]

- Shinberg DS. An event history analysis of age at last menstrual period: Correlates of natural and surgical menopause among midlife Wisconsin women. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;46:1381–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)10085-5. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)10085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr J, Taylor M, Hart C, Davey Smith G, Whalley L, Hole D, Wilson V, Deary IJ. Childhood mental ability and blood pressure at midlife: Linking the Scottish Mental Survey 1932 and the midspan studies. Journal of Hypertension. 2004;22:893. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200405000-00009. doi:10.1097/00004872-200405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, Hart C, Davey Smith G, Starr J, Hole D, Whalley L. Deary IJ. Childhood mental ability and smoking cessation in adulthood: Prospective observational study linking the Scottish Mental Survey 1932 and the Midspan studies. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:464–465. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.6.464. doi:10.1136/jech.57.6.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren S, Boshuizen H, Knook D. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 1999;18:681–694. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<681::aid-sim71>3.0.co;2-r. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<681::AID-SIM71>3.3.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley L, Deary IJ. Longitudinal cohort study of childhood IQ and survival up to age 76. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:819. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7290.819. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7290.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley L, Fox H, Starr J, Deary IJ. Age at natural menopause and cognition. Maturitas. 2004;49:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2003.12.014. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. Individual differences as predictors of accidents in early adulthood (Unpublished doctoral) Waco, Texas: Baylor University; 2008. [Google Scholar]