Abstract

Mortality and morbidity in patients with solid tumors invariably results from the disruption of normal biological function caused by disseminating tumor cells. Tumor cell migration is under intense investigation as the underlying cause of cancer metastasis. The need for tumor cell motility in the progression of metastasis has been established experimentally and is supported empirically by basic and clinical research implicating a large collection of migration-related genes. However, there are few clinical interventions designed to specifically target the motility of tumor cells and adjuvant therapy to specifically prevent cancer cell dissemination is severely limited.

In an attempt to define motility targets suitable for treating metastasis, we have parsed the molecular determinants of tumor cell motility into five underlying principles including cell autonomous ability, soluble communication, cell-cell adhesion, cell-matrix adhesion, and integrating these determinants of migration on molecular scaffolds. The current challenge is to implement meaningful and sustainable inhibition of metastasis by developing clinically viable disruption of molecular targets that control these fundamental capabilities.

Keywords: Migration, Metastasis, Motility, Therapy, Tumor, Adhesion, Invasion, Intravasation

1. Intro

Metastatic disease remains the primary cause for cancer-related deaths [1]. Whether it is present at the time of diagnosis, develops during treatment, or occurs at the time of disease relapse, the dissemination of tumor cells from the primary lesion is the principle reason for the mortality and morbidity of cancer patients. Surgical resection of the primary lesion, along with cytotoxic and cytostatic systemic therapy has been relatively successful in treating benign, localized cancer and preventing its progression to metastatic disease. Metastases, however, remain difficult to treat and render the disease incurable. Paradoxically, the more effective cancer treatment is at prolonging life, the greater the risk of metastasis. To combat the risk for eventual metastasis, many patients are over-treated with the intent of preventing dissemination of their disease.

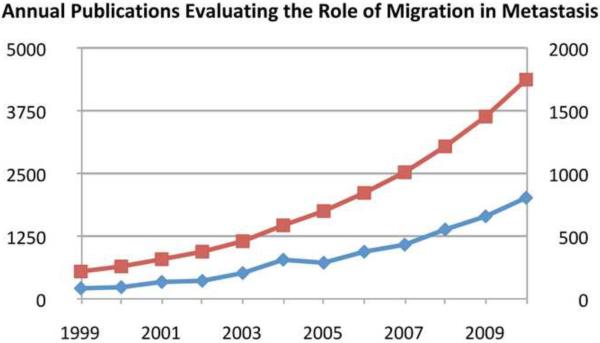

Therapies that specifically target the motility of tumor cells could significantly improve cancer treatment by removing the threat of systemic disease and decreasing the dependency on therapeutics with detrimental side-effects. For the past 5 decades the processes involved in tumor cell metastasis have been microdissected in an attempt to identify therapeutically viable targets. The central, defining process of metastatic disease is the ability of tumor cells to mobilize, invade, and cross normally non-permissive tissue barriers. This has greatly intensified the investigation into molecular mechanisms of motility and their contribution to metastasis (Fig. 1). Here, we provide an overview of these investigations and examine the potential for targeting tumor cell motility in the treatment of metastasis.

Figure 1. Total and annual number of pubmed listed publications targeting migration in metastasis.

WWW.Pubmed.gov was searched for articles with the keywords “Migration” and “Metastasis” in title and/or abstract. The data is presented as the number of publications/year (blue) and the cumulative number of articles in the field up to and including the indicated year.

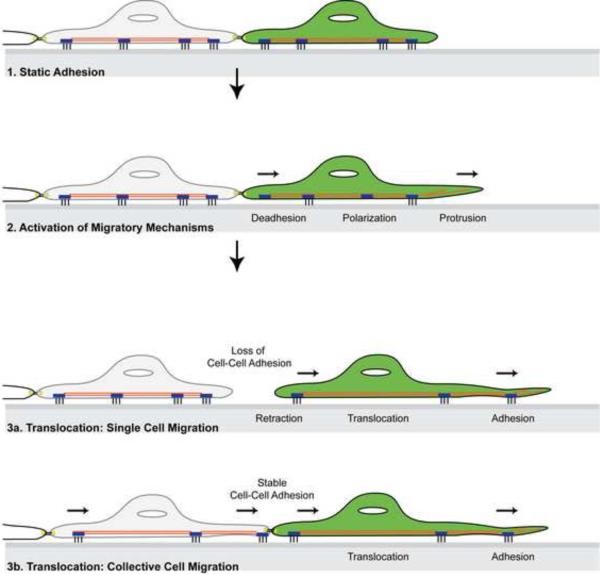

The migration of adherent cells is defined as the translocation of cells from one location to another. Detailed discussion is available from the Cell Migration Consortium on the Cell Migration Gateway (www.cellmigration.org). Typically, migration is parsed into five component processes: polarization, protrusion, adhesion, translocation of the cell body, and retraction of the rear (Fig. 2, [2, 3]). Although it is mechanistically convenient and sometimes necessary to define cell migration in this manner, the movement of cells within a living organism is highly complex, tightly regulated, and carefully coordinated. The physiology of cell migration is also very diverse. Some cell types such as activated hemopoietic cells exhibit a highly individualized “ameboid” movement with little adhesion and no matrix remodeling. Fibroblasts, and melanocytes generally migrate in a “mesenchymal” fashion as individual cells which are highly adherent and require proteolytic remodeling of the matrix. The migration of neuronal and smooth muscle cells is collective, directionally coordinated, and mechanistically integrated. Epithelial cells, the cell type from which most cancers originate, can exhibit multiple migration phenotypes. While epithelial cells are generally present as stationary, tightly interconnected sheets of cells, they can be mobilized during development, physiological homeostasis, and wound repair. Depending on their developmental differentiation, environmental stimuli, and surrounding tissue architecture, epithelial cells can migrate as collective sheets, clusters, tubular structures, or as individual cells (reviewed by Friedl and colleagues in [4, 5] and Rørth et al in [6]. Interestingly, in patients with malignant disease, tumor cells are found as both individual cells and organized collective sheets or clusters, suggesting that tumor cells in vivo exhibit the plasticity to switch between single and collective cell migration.

Figure 2. Cell migration.

A basic representation of cellular behavior during migration. Migration is parsed into five component processes: polarization, protrusion, (de)adhesion, translocation of the cell body, and retraction of the rear. Successful motility can be accomplished as isolated, individual cells (3a) or collectively as a group of cells (3b).

Tumorigenesis is largely driven by the subversion of normal cellular processes that control cell proliferation and cell death. It is therefore not entirely surprising that molecular mechanisms that control cellular motility in normal physiology reappear in metastatic cancer. However, unlike normal migrating cells, metastatic tumor cells no longer respond to contact inhibition and are capable of crossing non-permissive barriers.

2. Tumor cell motility is a therapeutically viable target for the treatment of metastasis

Despite the growing evidence implicating tumor cell motility in metastasis, there remains uncertainty about the viability of targeting motility with the intent of treating metastasis. There is evidence for both active and passive mechanisms of cancer dissemination [7][8]. Furthermore it has been suggested that the transient contribution of tumor cell motility to metastasis does not make it a suitable clinical target [7]. These factors raise the question: Can the inhibition of motility contribute therapeutically to the treatment of metastatic cancer? Here we have synthesized data in the field and suggest that the answer is “yes”.

Experimental, empirical, and clinical findings indicate that therapies targeting motility would be effective at treating metastasis. In the clinic, much of the metastatic risk assessment is based on the potential for the cancer to mobilize and cross non-permissive tissue barriers. In basic research, the migration machinery has been shown to promote dissemination. Most importantly, there is a strong correlation between the molecular mechanisms of migration and the progression to systemic disease [9]. Thus, the molecular mechanisms that promote tumor cell motility offer several inroads for novel drug design and clinical intervention designed to limit cancer progression towards overt metastasis and to treat existing metastatic disease. These include:

Anti-migration therapy may support active surveillance in the clinic. Cancer patients at risk for developing systemic disease are treated aggressively. This strategy is associated with high morbidity, poor quality of life, and elevated risk of treatment complications. Targeting motility could be implemented as a preventative measure to enable the physician to keep a patient under active surveillance without risking the appearance of systemic disease.

Targeting tumor cell motility within the primary tumor could limit local invasion. Invasive neoplasia, such as glioblastoma and pancreatic cancer aggressively infiltrate adjacent tissues and can be incurable even in the absence of overt metastasis to distant organs. Surgical intervention is frequently ineffective and disease often recurs. Targeting motility could improve therapy of these malignancies by preventing further infiltration and expansion into normal tissues.

Patients with overt metastases may benefit from treatments that block further dissemination. The paradigm suggesting that dissemination to the lymph nodes is the first step in a metastatic cascade [10] has been challenged in the clinic by the absence of improved survival after removal of regional lymph nodes [11]. In fact, it was demonstrated that occult micrometastases are not indicative of disease free survival [12]. These observations suggest that the cells responsible for metastases have yet to be mobilized from the primary site and would therefor remain susceptible to anti-migration therapy.

Restricting tumor cell motility may limit “evolution” towards an increasingly metastatic phenotype. Tumor cells exhibit an epigenetic diversity and plasticity that contributes to the selective evolution of metastatic abilities. This is evident from the pro-motility gene expression profiles seen in metastatic cells [13] and the in vivo selection of tumor cells with increasing metastatic ability [14, 15]. Once tumor cells disseminate away from the primary site, these two elements support the evolution and expansion of metastatic cells. The role of motility in the evolution of a metastatic phenotype is supported by evidence of the primary tumor re-seeding itself with circulating tumor cells[16]. Similarly, existing metastases can reseed to unaffected tissues expanding the burden of metastatic disease (reviewed extensively in [17]). Preventing the dissemination of tumor cells may therefor limit the Darwinian evolution of the metastatic phenotype.

Anti-motility strategies provide a unique mechanism to prevent the development of systemic disease and limit cancer-related death. Equally important, a successful anti-motility strategy may diminish the need for overly aggressive cytotoxic therapies currently used to avert the risk of metastatic dissemination.

3. Metastasis and the role of tumor cell motility

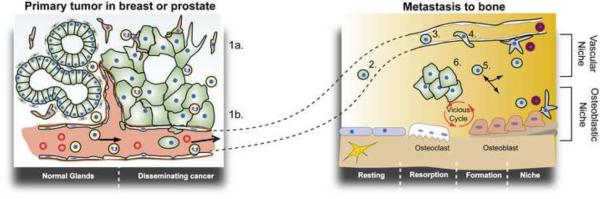

In order for a tumor cell to disseminate to a distant site, it must detach from the primary lesion, invade locally, and travel to a distant site where it can survive and proliferate (Fig. 3). Dissemination occurs via three avenues: 1) local invasion of normal tissues adjacent to the tumor, 2) infiltration of the draining lymphatic system, or 3) hematogenous metastasis through the vasculature [7]. Although large numbers of circulating tumor cells can be detected in tumor-bearing animals, metastatic colonization is remarkably inefficient [14]. The metastatic inefficiency of cancer cells is, in part, because successful metastatic dissemination requires the completion of each step in a complex sequence of events (Fig. 3). The interrelated and sequential nature of this metastatic cascade greatly diminishes the probability that any single tumor cell will give rise to a metastatic lesion.

Figure 3. The metastatic cascade.

Malignant tumor cells become mobilized and invade the local microenvironment (1a) and intravasate into the tumor vasculature (1b). Circulating tumor cells travel to a secondary tissue (bone) via the blood supply (2) and arrest in the venous supply of the recipient organ (3). Arrested cells subsequently extravasate (4) and invade the bone microenvironment (5). Within the bone, tumor cells can enter a protective niche where it remains as occult or dormant disease. When the tumor cell engages a favorable microenvironment it can engage the osteoblasts and initiate a feed-forward loop (vicious cycle) that promote growth in further infiltration of the bone microenvironment (6).

The inefficiency of metastasis has raised the question of whether tumor cells disseminate via passive or active migration-dependent mechanisms [7]. Three basic principles appear to determine the efficiency by which clinically overt metastases are formed: 1) Tumor-host interactions: tumor-host interactions control metastatic progression as tumor cells depart the primary lesion and enter a new environment, 2) Tissue structure and biomechanics: tissue structure and the biomechanics of the vasculature determine the route and distribution of circulating tumor cells, and 3) Pro-metastatic molecular determinants: the acquisition of pro-metastatic molecular determinants previously absent in the primary tumor. The latter can be acquired through a transient epigenetic plasticity such as the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [18, 19] or an evolutionary selection of epigenetic and genetic changes [20].

3.1 Tumor host interactions

In 1889, Paget hypothesized that disseminating tumor cells, which he called seeds, could reach most, if not all, organs but that successful metastasis was determined by selective growth in specific tissues (the soil) [21]. This became known as the “seed-to-soil” hypothesis. In subsequent years, extensive interrogation of tissue-specific metastasis validated this hypothesis (reviewed in depth by Weiss [22] and Fidler [14]). Reciprocal interactions between tumor and host cells can establish a positive feed-forward loop that supports tumor expansion. Consequently, normal tissue containing tumor cells can support metastatic growth. For instance, bone is a preferred metastatic site for both prostate and breast cancer metastases [23] while lung is preferred by metastatic cells from melanoma and renal cancer. The reciprocal interaction between tumor and host has been investigated extensively in recent years. At the primary site, tumor-associated fibroblasts and inflammatory cells contribute to an environment that supports malignant cancer [24–26]. Similarly, reciprocal communication between cancer cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts establish a feed-forward loop in which tumor cells promote the destruction of bone and the release of tumor-supporting growth factors from the bone [23]. More recently, it was demonstrated that systemic communication between the primary cancer, the bone marrow, and future metastatic sites can result in the formation of tumor-supportive conditions (pre-metastatic niche) prior to the arrival of metastatic cells [27]. There is, in fact, increasing evidence to suggest that motility in the local microenvironment and systemically across the circulatory system involves intricate tumor-host communication.

3.2 Tissue structure and biomechanics

Systemic dissemination requires that tumor cells access the vasculature and travel via the circulatory system to a distant site where the cells extravasate and establish secondary tumor growth (reviewed comprehensively by Weiss [22] and Fidler [14]). Ewing and colleagues postulated [28] that metastatic inefficiency was related to the location of the tumor within the body, the anatomic structure of the vasculature, and the biomechanics of tumor cell transportation. The contribution of tissue biomechanics to cancer metastasis and to the randomness of colonization were further explored by Weiss [22, 29]. Indeed, gross anatomical evaluation shows that colorectal cancer metastasizes predominantly to the nearest vascular bed in the liver, pancreatic cancer invades aggressively to adjacent organs and the surrounding viscera, and ovarian cancer cell dissemination is almost exclusively restricted to the peritoneal cavity. While it is certainly true that the capillary bed immediately downstream of the primary tumor is exposed to a greater number of circulating tumor cells, overt metastasis from numerous types of cancer is predominately site specific. This was conclusively, albeit inadvertently, shown in patients with metastatic ovarian cancer [30]. These patients received peritoneovenous shunts to alleviate tumor-induce ascites but they developed no overt distant metastases in spite of the circulating, malignant cells. These observations confirm that mere, inadvertent, passive access to the circulatory system is not sufficient to accomplish metastatic growth.

3.3 The acquisition of pro-metastatic molecular determinants

The identity of genes responsible for tumor cell metastasis and tissue tropism has been the subject of intense investigation. These studies aim to develop a mechanistic understanding and identify clinically viable targets for the treatment of metastatic disease. Expression analysis of clinical specimens and experimental models with divergent metastatic abilities identified a very large number of genetic determinants that control the metastatic process [13]. Furthermore, an evaluation of cancer's epigenetic plasticity revealed an inherent ability of metastatic cells to alter the expression of these determinants in a changing environment. The Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) is an example of cancer cell plasticity in which epithelial-derived cancers adopt a mesenchymal behavior. During EMT, the adhesive repertoire is significantly altered and includes a reduction in E-cadherin,a gain of N-Cadherin, as well as changes in cytoskeletal organizing proteins, and the expression of developmental transcription factors to gain migratory and invasive properties [19]. These epigenetic changes often occur transiently in response to growth factor stimuli such as TGFβ and HGF. More permanent changes can clearly evolve within the heterogenous tumor cell population. In vitro and in vivo selection reveals relatively stable epigenetic changes that support metastatic behavior and tissue-specific metastasis. These changes presumably arise as a consequence of alterations in DNA accessibility through changes in DNA methylation, histone modification, and genomic imprinting [31, 32]. Unlike the transforming events of carcinogenesis, genetic alterations are relatively rare during metastasis. Instead, metastasis is associated with the accumulation of multiple epigenetic modifications. Many of these modifications drive the mobilization of metastatic tumor cells.

3.4 Tumor cell motility

The contribution of tumor cell motility to metastasis is evident in each of the three principles discussed above:

Tumor-host interactions can promote tumor cell motility by providing chemotactic stimuli [33], remodeling the tissue to alleviate its non-permissive and motility-suppressive characteristics, and providing guidance cues to promote directional migration [34].

The vascular anatomy and architecture of tumor vasculature is responsible for creating hypoxic regions, oxygen, and nutrient gradients as well as preferred points of vascular entry/exit [35, 36]. Moreover, recent investigations into mechano-transduction demonstrate that tissue rigidity in the primary tumor and the bone contributes to the motility of tumor cells [37–39].

Molecular determinants that enable cell autonomous motility are seen in almost every expression profiling of metastatic cells. Although a large number of changes occur in the transition from benign to invasive disease, a signature of motility-related genes is evident both in experimental models and patient specimens. In some instances these pro-migratory gene profiles are transiently induced by the environment of the primary tumor or the metastatic site while in other instances the profile is the product of a more persistent reprogramming of the tumor cell [13, 34, 40–43].

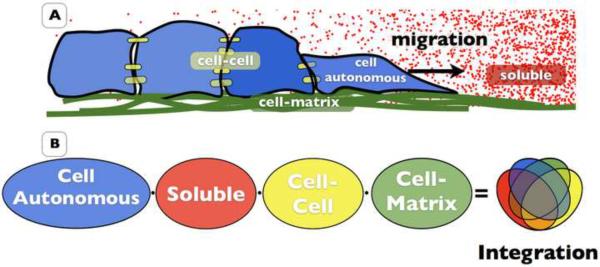

Ultimately, it is the contribution of these three principles that determines the mobility and metastatic ability of a tumor cell (Fig. 4). The key to targeting tumor cell motility for therapeutic means lies in the identification of a molecular mechanism required for tumor cell motility that is sufficiently cancer specific to prevent disruption of normal physiology.

Figure 4. Classification of cell migration determinants.

The innumerable molecular determinants that contribute to tumor cell motility can be classified in one of five underlying principles. Cell autonomous migratory ability includes the intrinsic determinants that enable a cell to move. Soluble communication includes an autocrine and paracrine communication. Cell-Cell adhesion includes those determinants responsible for physical cell-cell adhesion and communication. Cell-matrix adhesion includes those determinants responsible adhesion to and migration on the ECM. Molecular integration includes the molecular scaffolding components that allow for the integration of all molecular

I. Mechanisms that regulate cell motility

Cell migration broadly refers to processes involved in the movement of cells from one location to another. For adherent cells, translocation requires dissociation at the point of origin, physical displacement of the cell body, and re-adherence in another location. While this process appears relatively simple, it is in fact a process of immense biological complexity. Cell migration requires the integration of numerous molecular mechanisms that allow a cell to coordinate the formation of new adhesions while disengaging existing adhesions and simultaneously exerting force to move the cell body. Among the adhesion receptors alone there are four large families: the immunoglobulin superfamily cell adhesion molecules, the integrins, the cadherins, and the selectins [44–46]. These adhesion receptors engage immobilized ligands including structural and matricellular proteins of the extracellular matrix or cell-surface ligands on adjacent cells. Scaffolding proteins and signaling molecules mediate intracellular connections of the cytoskeleton with the cytoplasmic tail of adhesion receptors [47, 48].

Subsequent remodeling of the cytoskeleton transmits force between distant portions of the cell allowing the cell body to migrate to a new location where new adhesions are established. Extracellular stimuli such as cytokines are generally required to initiate and sustain activation of the molecular migration machinery. When a tumor cell encounters a non-permissive barrier such as a basement membrane, the production of proteolytic enzymes, a change in adhesion receptors, and the expression of a pro-migratory matrix can enable a cell to penetrate the barrier and disseminate from the tissue in which it was originally retained [49, 50]. Close coordination of these adaptations is necessary for successful metastatic dissemination.

Considering the complexity of migration, it is impossible to rigorously review all the molecular determinants of migration and identify all of the potential areas for clinical intervention. Rather than adding increasing layers of complexity to the existing literature we parsed the molecular determinants into the five underlying principles that collectively dictate tumor cell motility (Fig. 4).

These include:

-

1)

Cell autonomous ability

-

2)

Soluble communication factors

-

3)

Cell-cell adhesion

-

4)

Cell-matrix adhesion

-

5)

Integrating molecular determinants of migration

The following sections discuss in detail the broad functional contribution of each principle category, we provide representative examples that are possible targets suitable for invention in tables I–V, and we provide an extensive overview in Table VI of ongoing translational work attempting to target tumor cell migration in the clinic.

Table 1.

Targeting molecular mechanisms that support cell autonomous migration.

| Target | Molecular Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Ras/Rho/CDC 42 | Small GTPases involved in the reorganization of actin and microtubulin network formation that controls cell protrusions (lamellipodia and filopodia) | [52] |

| Snail, Twist | Transcription factors that functions as a regulators of the EMT phenotype promote migration and tumor cell motility | [63, 105, 106] |

| SATB1 | Transcriptional regulator (chromatin organizer and transcription factor) that ntegrates higher-order chromatin architecture with gene regulation. Ectopic SATB1 expression promotes aggressive phenotype while its downregulation promotes E-cadherin expression and inhibits the transcription factors Snail and Twist. | [64, 185] |

| Src | A non-receptor tyrosine kinase that transmits integrin-dependent signals central to cell movement and proliferation | [55, 107] |

| WAVE3 | An actin nucleation/polymerizing factor that binds actin and the Arp2/3 complex. It is an effector molecule involved in the transmission of signals form tyrosine kinase receptors and small GTPases to the actin cytoskeleton. Normally expressed in ovary in brain but ectopic expression can occur at high leves in diverse cancers where it promotes motility and metastasis. | [183, 184] |

| miRNA-10b, miR34a | microRNA can regulate expression of a large group of genes that control migration. Both upregulation of migration promoters and down regulation of migration inhibitors has been observed. | [43] [67] |

Molecules included here are representative molecular determinants of the underlying principle

Table V.

Targeting mechanisms that support molecular integration.

| Target | Molecular Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CD151 | Transmembrane scaffolding protein of the Tetraspanin Super Family. CD151 interacts with other tertraspanins as wel as unique partners including integrins α3β1 and α6β1, MMP14, MMP7, PKC, PI4K and other. These tetraspanin-partner dimers are incorporated into macromolecular complexes known as tetraspanin-enriched microdomains through the homo- and hetero-dimerization of the tetraspanins. | [98, 99, 169] |

| Talin-1 | Integrin adaptor protein that binds to the cytoplasmic tail of the β subunit tail and links the integrin to the actin cytoskeleton and complexes Vinculin and FAK into a functional complex that controls inside-out activation of the integrin and outside-in signaling resulting from matrix binding. Silencing Talin reduces metastasis | [154–156] |

| FAK | Non-receptor tyrosine kinase that binds to Focal Adhesion Complexes by binding Talin and Paxillin. It interacts with a wide variety of signaling molecules including src, PI3K, Shc, PLCγ, P130Cas, RhoGEF, GRB2, and more. Phosphorylation of its partners by FAK regulates motility. | [165–168] |

| P120 Catenin | Intracellular scaffolding protein of the catenin family that stabilizes the formation of E-Cadherin based adhesions and integrates cadherin, src, and RTK signaling through scafolding of intracellular signaling molecules. P120 is frequently lost or mutated in cancer thereby disrupting the function of E-cadherin and other, currently undefined, signaling components. | [87, 88, 157] |

| Cortactin | Actin binding protein that also binds to WASP, MIM, Hax-1, TEM7, Dynamin 2, CD2AP, and Cadherins. Cortactin seems to be important for invasive activity associated with invadapodia present in invasive cells. Cortactin is strongly correlated with cancer progression although its specific role remains unclear. | [162–164] |

| SPARC | Matricellular protein capable of interacting with collagen, fibronectin, EGF, TGFβ, and the β1 integrin. It alters the composition, assembly, and maturation of ECM. SPARC is upregulated in a large number of cancers although its biological contribution to metastasis is very context dependent. | [158, 159] |

| P130 CAS | Intracellular scaffolding protein defined as an integrin adaptor molecule. P130cas is capable of binding a very broad range of cytoplasmic signaling molecules including FAK, PYK2, FRNK, PTPNI2, RAPGEF1, CRK, NCK, SFK, Aurora A, and PI3K. It is participates in both transformation and migration. | [91, 160, 161] |

Molecules included here are representative molecular determinants of the underlying principle

Table VI.

Migration inhibitors in clinical development

| Drug | Target | Company | Clinical Phase | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Cell autonomous | ||||

|

| ||||

| Saracatinib (AZD0530) | Src | AstraZeneca | II | [126] |

| Bosutinib (SKI-606) | Src | Wyeth | II, III | [127] |

| Dasatinib (BMS-354825) | Src | Bristol-Myers Squibb | I, II | [128] |

| Fasudil | Rho kinase | Asahi Kasei | I, II, III | [129] |

| Emodin | Cdc42/Rac1 | I | [130] | |

|

| ||||

| Soluble interactions | ||||

|

| ||||

| CTCE-9908 | SDF-1 | Chemokine Therapeutics | I, II | [131] |

| MetMAB (PRO143966) | Met | Roche/Genentech | II | [132] |

| AMG 208 | Met | Amgen | I | Clinical Trial NCT00813384 |

| GC1008 | TGF-β family | Genzyme | I, II | J Clin Oncol 26:2008 (ASCO Abstr. 9028) |

| Trabedersen (AP 12009) | TGF-β2 | Antisense Pharma | I, II | [133] |

| Infliximab | TNF-α | Centocor | I, II | [134] |

| EGFR | Herceptin^ (trastuzumab) | Genentech/Roche | I, II, III | Trial NCT00807859 |

| VEGF | Avastin^ | Genentech/Roche | I, II, III | Clinical Trial NCT00391092 Clinical Trial NCT00333775 |

| CXCR-4 | CTCE-9908 | Chemokine Therapeutics | I, II | [146, 147] |

|

| ||||

| Cell-cell interactions | ||||

|

| ||||

| IGN-101 | EpCAM | Aphton | I, II | J Clin Oncol 26: 2008 (ASCO Abstr. 15) |

| Exherin (ADH-1) | N-cadherin | Adherex | I, II | [135] |

|

| ||||

| Cell-matrix interactions | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cilengitide (EMD121974) | αvβ and αvβ5 integrins | EMD/Merck KGaA | II, III | [136] |

| Volociximab (M200) | α5β1 integrin | PDL/Biogen Idec | II | [137] |

| Etaracizumab (Abegrin) | αvβ3 integrin | MedImmune | I, II | [138] |

| ATN-161 | Integrins | Tactic Pharmaceuticals | I, II | [139] |

| BMS-275291# | MMPs | Bristol-Myers Squibb | I, II, III | [140] |

| Endostatin | MMPs | Alchemgen Therapeutics | III | [141] |

| Curcumin | MMPs | Sabinsa Corporation | I, II | [125] |

| Tigapotide (PCK3145) | MMP9 | Ambrilia Biopharma | II | [142] |

| A6 | CD44 | Angstrom Pharmaceuticals | II | Clinical Trial NCT00083928 |

| Mesupron (WX-671) | uPA | Wilex | I, II | [143] |

| ATN-658 | uPA | Tactic Pharmaceuticals | I | http://www.tacticpharma.com/ATN-658.html |

| Tempostatin (Halofuginone hydrobromide) | Stroma | Collgard Pharmaceuticals | II | [144] |

| PI-88 | Heparanase | Progen | I, II, III | [145] |

| Vitaxin | αvβ3 | MedImmune | II | Trial NCT00072930 |

|

| ||||

| Molecular integration | ||||

|

| ||||

| CFAK-C4 | FAK | CureFAKtor Pharmaceuticals | I | www.curefaktor.com |

| PF-562271 | FAK | Pfizer | I | J Clin Oncol 28: 2010 (ASCO abstr. 2553) |

Small molecule inhibitors capable of blocking EGFR and VEGFR kinase activity (compound A and B respectively) have also been developed and are currently being evaluated in advanced and metastatic disease. Resistance to both Herceptin and Avastin occurs frequently.

Broad MMP inhibitors failed in the clinic due to their negative impact on normal tissue remodeling. Enzyme-specific MMP inhibitors are currently pursued for a more directed approach. For instance ADAM17 inhibitors may inhibit TNFα activation and shedding of IgSF members.

Cell Autonomous Ability

Within the human body, each cell type exhibits a distinct autonomous ability to migrate that varies depending upon the molecular mechanisms that remain available to it after developmental differentiation (reviewed extensively by Friedl et al [5, 51] and Table I). During metastasis, the cell's autonomous migratory ability appears to be driven by the activation of latent mechanisms, the aberrant recruitment of endogenous mechanisms, and/or the ectopic expression of developmentally suppressed migratory mechanisms.

The cell's autonomous migration potential is most apparent in it's ability to remodel its cytoskeleton. Of the three cytoskeletal filaments (microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules) remodeling actin microfilaments is the most studied. This innate, autonomous ability involves hundreds of molecular determinants that control actin polymerization, extension, stabilization, and depolymerization. During migration, these filaments influence cell shape, transmit force, and support cargo trafficking. Key molecular determinants of the endogenous migratory ability include the small GTPases (Rho, Rac, CDC42)[52] which initiate cytoskeleton remodeling, while members of the Actin Related Proteins (Arp2/3) mediate actin remodeling, and motor proteins of the myosin family control cell protrusion, contraction and cargo motoring. The extent to which autonomous migration contributes to motility was elegantly revealed by Lämmermann and colleagues in a study of 3D-migration of leukocytes from which all integrins were ablated [53]. Surprisingly, the integrin-negative leukocytes are perfectly capable of migrating in vitro and in vivo. These cells migrate by the sole force of actin-network expansion, which promotes protrusive flowing of the leading edge [54]. Thus the ability to regulate the cell's cytoskeletal structure can determine its inherent migratory capacity and contribute to the metastatic potential of cancer (Table I).

The non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src is another example of a cell-autonomous molecular determinant that is frequently and aberrantly activated in malignant cancer. Discovered originally as a viral oncogene [55], Src is overexpressed and ectopically activated in a myriad of cancers [56]. Experimental evidence and current clinical trials indicate that this kinase is a fundamental driver of cell motility and tissue invasion. Src influences tumor biology by driving proliferation, altering gene transcription, and regulating adhesion, invasion and motility. Src mediates these functions through activation of a large number of substrates including key components of the focal adhesion complex, (vinculin, cortactin, talin, paxillin, FAK, tensin, ezrin and p130Cas), junctional proteins, (β - and γ -catenin, ZO-1, occludin, p120ctn, connexin 43, nectin-2) [54][57, 58], enzymes involved in phospholipid metabolism, (PLC-γ, p85 subunit of PI3-kinase) and signaling molecules (p190RhoGAP, p120rasGAP, Eps8) [57] [59, 60].

Unlike its enzymatically active counterparts, the Wiskcott Aldrich Proteins (WASP) and WAVE family proteins [61] promote actin remodeling through the activation of Actin Related Proteins (ARPs). Together, members of these protein families facilitate the polymerization of new actin strands and promote protrusion of the cell's leading edge. Individual family members are selectively expressed and ectopic expression increases cell autonomous motility and facilitates metastatic dissemination [62].

Although individual molecular determinants are often emphasized, it is increasingly evident that entire pro-migration gene signatures occur in metastatic cells [34]. Transcriptional regulators influence cell autonomous motility by controlling the protein pools available for cytoskeletal rearrangements by regulating their expression. The aberrant and ectopic expression of transcription regulators is a recurring theme in cancer metastasis. Snail, Twist [63], and SATB1 [64] reappear in metastatic cells and drive a motility-promoting expression profile that enables tumor cells to mobilize. Conversely, broad regulation of motility genes by microRNA was identified recently [65]. Upregulation of the miRNA-10b may reduce expression of motility suppressor genes such as HOXD10 [43] while genomic loss of miRNA101 [66] results in the overexpression of metastasis associated histone methyltransferase EZH2. Similarly, reduced expression of miR34a is apparent in aggressive prostate cancer. This miR has been evaluated preclinically as a therapeutic agent against prostate cancer metastasis [67]. Targeting microRNA may be clinically efficacious because this treatment impacts cellular behavior by altering expression for a group of genes that collectively control migration.

Soluble Communication

Soluble mediators, ranging from small molecules to macromolecular protein complexes, enable communication between tumor cells and their environment without direct contact. Mediators produced by tumor and host cells within the local microenvironment provide paracrine and autocrine support for cellular movement (Table II). Soluble factors produced within the tumor tissue also act systemically to mobilize cells from the bone marrow or to influence host cells in a putative metastatic site. Conversely, the host can provide systemic soluble mediators that influence cellular behavior in the primary tumor and the metastatic lesions.

Table II.

Targeting molecular mechanisms that enable soluble communication.

| Target | Molecular Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| TGFβ | TGFβ ligands (a 40-member superfamily that incudes TGFβ1, 2, and 3) control cellular growth, differentiation, and motility through heteromeric signaling complexes composed of the TGFβ type I, II, and III receptors. Neutralizing antibodies can diminish metastasis. | [108–111] |

| VEGF | Ligands that belong to the VEGF-PDGF super family where the VEGF gene yields five isoforms (A–D) that bind to four receptors (Flt-1, Flk-1, neuropilin-1, and Flt-4). | [180–182] |

| EGF | The EGF family includes ten ligands that bind to dimeric ERBB receptors to induce pro-migratory signaling via receptor tyrosine kinase activity. Currently a target of many anti-cancer therapeutics, EGF receptor is upregulated in many cancers (breast, colorectal, lung). | [33, 112–114] |

| SDF-1 | A soluble cytokine that binds to its cognate receptor CXCR4. First recognized for its broad impact on immune functions and ability to control homing of bone marrow cells, it is also involved in the homing of tumor cells to distant sites. | [177–179] |

| TNFα | The most studied member of the tumor necrosis family of cytokines first recognized as a regulator of the immune response. It is produced by a large number of human tumors. The highest levels of TNF-α is secreted by foreign leukocytes present in the tumor microenvironment. Plays a dual role as about both a tumor suppressor and tumor promoter. High serum expression in patients is associated with a poor prognosis. | [68, 115, 116] |

Molecules included here are representative molecular determinants of the underlying principle

Tumor-derived mediators

Tumor cells produce a myriad of cytokines that influence the biology of the tumor as well as the local host stroma. EGF, HGF, and TGFβ generated by the tumor act in autocrine and paracrine fashion to mobilize both tumor and host cells. In many instances tumor-derived cytokines promote motility indirectly via the host stroma. The exposure of fibroblasts to the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α promotes their differentiation into cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs,[68]). CAF promote tumor cell motility through the induced expression of paracrine acting cytokines and by physically encouraging the invasion of tumor cells [69].

Tumor-derived mediators can also have a significant systemic influence on metastasis. Specific cytokines, such as VEGF-A, placental growth factor (PLGF), granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF), stromal cell derived factor-1 (SDF1) and osteopontin, secreted by the growing tumor can impinge upon the bone marrow (BM) via the peripheral circulation. These factors can switch the quiescent microenvironment in the BM compartment to a highly pro-angiogenic and pro-tumorigenic state that promotes the expansion and mobilization of progenitor cells into the peripheral circulation. These cells engage the primary tumor and develop a favorable metastatic environment in distant organs (premetastatic niche) in response to SDF-1, TNFα, TGFβ, and PLGF [27, 70].

Host-derived mediators

Tumors recruit a wide variety of stomal cells including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, inflammatory cells, and bone marrow derived cells such as mesenchymal stem cells. These stomal cells can promote tumor cell motility through the production of a variety of soluble mediators like EGF, HGF, TGFβ, HGF, and CCL5 [70, 71]. In many instances, a pro-metastatic reciprocal interaction supports paracrine signaling between tumor and host. Tumor cells recruit mesenchymal stem cells which promote tumor cell motility through the production of CCL5 [72]. Macrophages are similarly recruited to the invasive front by tumor-derived CSF-1 where they induce tumor cell chemotaxis through the release of EGF [33].

Collectively, host and tumor derived soluble factors enable communication between the cancer and its environment. It is the activation or suppression of the migration machinery in response to these soluble factors that regulates the motility and dissemination of tumor cells.

Cell-Cell Interactions

While cell-cell interactions generally promote tissue cohesion, adhesive contacts between adjacent cells can both promote and inhibit motility. Cell-cell interactions are controlled at multiple levels, including the expression, localization, and surface presentation of cell adhesion molecules (Table III). Cell-cell adhesion receptors include members of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF), cadherins, integrins, selectins, ephrins, and the tight junction proteins claudins and occludins. Tissue specific expression of adhesion proteins creates a characteristic expression signature in cancers that reflects their tissue of origin. However, adhesive characteristics change in metastatic disease. A loss of firm adhesion promotes motility and metastasis which is evident in the loss or mislocalization of cadherins and tight junction proteins [46]. However, adhesion is rarely lost completely during metastasis, and new adhesive proteins are frequently upregulated or newly expressed to displace previously migration-suppressive adhesions. Such interactions include EpCAM, which can abrogate E-cadherin-mediated adhesion [73]. Cadherin switching from E-cadherin to N-cadherin can promote motility during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. The expression of even low levels of Ephrin A2 can promote motility and mediate metastasis by influencing other pro-migratory signaling events such as Src activation [74]. Several members of the immunoglobulin superfamily contribute to the motile behavior of tumor cells. ICAM, EpCAM, L1CAM, and ALCAM have all been associated with metastatic behavior [73, 75, 76]. Interestingly, these molecules exhibit a promigratory behavior but are not restricted to migratory cells. New understanding of IgSF shedding suggests that these adhesion molecules are selectively favored in cancer metastasis because their adhesion dynamic is readily augmented by pro-migratory stimuli [45]. Thus, changes to cellular adhesion that facilitate cell migration eventually promote cancer metastasis.

Table III.

Targeting molecular mechanisms that support cell-cell interactions.

| Target | Molecular Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| E-Cadherin | Cell-Cell adhesion molecule of the cadherin family involved in the regulation of epithelial cell-cell adhesion. Routinely mislocalized or lost in patients with metastatic disease. Experimental over expression can inhibit migration while knock down or cellular relocalization in response to pro-migratory cytokines can promote motility and migration. Generally considered a negative regulator of cell motility. | [40, 118, 176] |

| N-Cadherin | Cell-Cell adhesion molecule of the cadherin family involved in the regulation of epithelial cell-cell adhesion. Expressed during epithelial-mesenchymal transition and upregulated in metastatic disease. Upregulation frequently coincides with the loss of E-Cadherin. Association with FGFR-1 enhances receptor signaling and provides a prometastatic mechanism of motility | [117–119][120] |

| EpCam | Cell-Cell adhesion molecule of the immunoglobulin super family. Can function as a tumor suppressor or oncogene because it inhibit motility but also abrograte E-cadherin mediated adhesion to promote tumor cell motility. | [120, 121] |

| ALCAM | Cell-Cell adhesion molecule of the immunogobulin super family. Can inhibit motility when engaged in cell-cell interactions or promote motility when cleaved by ADAM17. Expression is upregulated in prostate, pancreatic, and colorectal cancer but down regulated in breast cancer. Shedding is elevated in all cancers and the shed ectodomain is being explored as a biomarker of metastasis. | [75, 174, 175] |

| Claudin 1, 4, and 7 | Cell-Cell adhesion molecule of the Claudin family involved in transmitting cell-cell contact to the actin cytoskeleton within the tight junction. Loss of Claudins enhances motility and metastasis. | [95, 122–124] |

| EphA2 | Cell-Cell adhesion molecule of the ephrin family capable of promoting motility and metastasis. Integrates with Src, Akt, and HGF-mediated signaling. | [74, 173] |

Molecules included here are representative molecular determinants of the underlying principle

Cell-Matrix Interactions

The dynamic interaction between a cell and its external matrix heavily influences cell migration and the invasive behavior of cancer cells. Cell-matrix interactions are formed between adhesive proteins on the surface of the migrating cell and the structural components of the extracellular matrix. These factors influence both the motility and migratory capacity of normal cells, and the metastasis of tumor cells (Table IV and [24]).

Table IV.

Targeting molecular mechanisms that support cell-matrix interactions.

| Target | Molecular Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Integrin αvβ3 | Matrix adhesion receptor of the integrin family involved in the adhesion to a wide variety of matrix components that exhibit the RGD sequence. These include collagen, vitronectin, and fibronectin. This integrin is also extensively expressed by the host vasculature and hemopoietic cells. | [148] |

| Integrin α2β1 | Matrix adhesion receptor of the integrin family involved in the adhesion to collagen and a few additional substrates. While the receptor facilitates motility on collagen it actually inhibits migration on non-collagen substrates and suppresses metastasis. | [77, 172] |

| Syndecan-1 | Transmembrane proteoglycan of the immunoglobulin super family. Syndecans have previously been considered as ligand gatherers, working as co-receptors in collaboration with signalling receptors but they can also signal independently. Syndecan-1 interacts with the ECM through its glycosaminoglycan side chains. Some reports suggest it can also engage in cell-cell adhesion. Loss of Syndecan-1 is specifically associated with metastasis. | [149–151] |

| MMP14 | Transmembrane metalloproteinase of the MMP family. MMP14 is a collagenase but also capable of cleaving aggrecan, elastin, fibronectin, gelatin, tenascin, nidogen, perlecan, fibrillin, and laminin. It can also cause shedding of Syndecan-1, and betaglycan (TBRIII). It can activate the MMP2 and MMP-13 activation. Its activity can be reguated by ALCAM and CD151. MMP14 is expressed in many metastatic cells and facilitates invasion. However, it is not required for metastasis. | [170, 171] |

| CD44 | Transmembrane receptor for hyaluronic acid and can also interact with other ligands, such as osteopontin, collagens, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Splice variant expression is correlated with motility and metastasis. Splice variant-induced changes in adhesion can facilitate migration and metastasis. | [152, 153] |

Molecules included here are representative molecular determinants of the underlying principle

The best studied family of proteins that regulate cell-matrix interactions are integrins, a family of heterodimeric cell-surface proteins, which contain an extracellular alpha and beta subunit. Similar to cell-cell adhesion molecules, some integrins suppress metastasis while others promote dissemination. Integrin α2β1 was recently identified as a metastasis suppressor. It is lost in mouse models of breast cancer and in breast cancer patients [77]. Conversely, the integrin αvβ3 promotes cancer metastasis [44, 78]. Non-integrin receptors are also involved in the migration of metastatic cells. Syndecan-1 is diminished in some cancers and upregulated in others, yet its ability to regulate adhesion and migration is primarily controlled by shedding [79]. Conversely, a change in splice variants of the hyaluronic acid receptor CD44 facilitates motility and metastasis by promoting matrix remodeling [80].

In addition to changing their adhesion receptor profile, metastatic tumor cells can cross non-permissive tissue barriers by remodeling the matrix that surrounds them. Matrix remodeling is accomplished through degrading existing matrix, producing new matrix components, and (re)organizing both new and exiting matrix protein within the existing tissue architecture. Matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) were among the first matrix remodeling enzymes including MMP2, 9, and 14 are found to be capable of promoting metastasis by degrading the matrix [49, 51, 81]. Along with serine proteases, MMPs are among the enzymes that enable tumor cells to penetrate the extracellular matrix by cleaving multiple matrix components including collagens, vitronectin, fibrinogen, and laminin. In some instances, cleavage of the matrix protein creates a pro-migratory stimulus [49]. This can be seen for laminin-332 cleaved by the serine protease Hepsin [82]. Conversely, the expression, deposition, and assembly of new, permissive extracellular matrix by the invading tumor cells that enables their migration further facilitates the metastasis of tumor cells. This is seen in the deposition of tenasin-C isoforms [83][84], fibronectin isoforms [85], collagen [86] and fibrin. Incorporation of new matrix and remodeling of the tumor extracellular matrix also changes the three-dimensional rigidity of tissues, frequently making the tissue less pliable. With this increasing rigidity, the motility of tumor cells increases [38] leading to increased invasion and cancer malignancy [37].

Although the extracellular matrix was initially perceived as a barrier to tumor cell dissemination, it is increasingly evident that the architecture and the matrix composition of the microenvironment can promote tumor cell dissemination.

Molecular Integration

Although a large number of molecular determinants influence migration, the contribution of any single component is regulated through its integration into the migration machinery. There are thousands of molecular determinants that can contribute to cell migration. Their integration occurs primarily at the level of molecular scaffolds that allow for a convergence of these individual mechanisms. A molecular scaffold generally consist of an adaptor protein capable of interacting simultaneously with several proteins which, together, regulate a single biological process. Adaptor proteins are found at every cellular level including the cytoplasm (P130CAS), the membrane (CD151), and the extracellular matrix (SPARC). Among all the therapeutic strategies currently under evaluation (Table V) there is only one molecular scaffold (FAK). However, the clinical focus on integration mechanisms is likely to intensify as our understanding of molecular scaffolds is rapidly increasing and their uniquely critical participation in migration may improve therapeutic efficacy. To emphasize its importance, four points of integration are presented below.

Integration of cell-matrix adhesion with cell-autonomous ability

Molecular integration of integrins with the cell autonomous migration machinery occurs primarily through Talin and Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK). Talin is a scaffolding protein that binds the cytoplasmic domain of β integrin subunit and links integrins to the actin cytoskeleton while complexing Vinculin and FAK into a functional complex that controls inside-out activation of the integrin and outside-in signaling resulting from matrix binding. As a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, FAK integrates with integrin associated complexes through the binding of Talin and Paxillin where it engages and controls the activity of a wide variety of cell autonomous signaling molecules including src, PI3K, Shc, PLCγ, RhoGEF, GRB2.

Integration of cell-cell adhesion with cell-autonomous ability

P120 is an adaptor protein of the catenin family and is frequently lost or mutated in cancer. Loss of P120 activity disrupts the function of E-cadherin and facilitates a promigratory phenotype. P120 interacts directly with the cytoplasmic tail of E-Cadherin and integrates cadherin, src, and RTK signaling through scaffolding of intracellular signaling molecules [87][88]. Its interaction with the zinc-finger transcription factor kaiso allows P120 to regulate gene transcription [89]. Regulation of GTPase signaling via P120 catenins has been established [90] but the identity of binding partners is currently unknown.

Integration of soluble communication and cell-matrix adhesion with cell-autonomous ability

P130CAS is a classic molecular scaffold that controls the integration of signaling between integrins, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), and Src. p130CAS binds to twelve known partners and is phosphorylated by both Src and FAK. Stimuli from cell-matrix adhesion (integrins), soluble communication (RTK), and cell autonomous ability (Src) each change the phosphorylation, localization, and activity/availability of P130CAS binding partners. Ultimately, the composition and activity of the macromolecular complex that contains P130CAS determine its ability to influence actin cytoskeleton remodeling, gene expression, and cellular survival [91].

Integration at the membrane with molecular scaffolds

The interactions between the cell periphery and its extracellular microenvironment [92] are organized through macrodomains within the membrane such as focal adhesions [93][94], tight junctions [95], lipid rafts [96], and tetraspanin-enriched-microdomains [97][98][99]. Together with their partner proteins, membranes scaffolding proteins arrange themselves into organized structures within the plane of lipid bilayer. This high-order structure controls availability as well as activity of partners associated with the scaffolding proteins [100].

Of the membrane scaffolding proteins, the 33-member family of tetraspanins is most prominently involved in cancer biology. Tspan 1, 7, 8, 13, 24, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 31 are involved in tumor progression [99]. Metastasis seems to be specifically promoted by Tspan24 (CD151, [99, 101]) and suppressed by Tspan27 (CD82, [102]). Tetraspanins function as membrane scafolding proteins by organizing a large selection of partner proteins into higher order structures usually referred to as tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TERM [98]). CD151 is an important regulator of tumor cell motility [99]. It interacts and organizes integrins (including α3β1 and α6β1), MMPs (including MMP7 and MMP14), tetraspanins (including CD9, CD81, CD82, and CD151), cytoplasmic signaling molecules (including PKC and PI4K) (Reviewed in detail in [101] and [98]). Tetraspanin expression is frequently altered in cancer [97] and direct targeting of CD151 can, in fact, inhibit metastasis [103].

The central organizing function of molecular scaffolds and adaptor proteins makes them very attractive clinical targets. Considering the limited success of cancer therapies that target individual proteases, growth factors, and kinases, altering the molecular integration of such prominent pro-migratory stimuli may prove to be most effective strategy for targeting motility and preventing metastasis.

II. Therapeutic targeting of tumor cell motility

Therapy that targets tumor cell migration has tremendous potential in the clinic. Ideally targeted therapy limits, intervenes, or disrupts a molecular process that supports the pathology without disrupting normal physiological function. Successful targeting of tumor cell motility with the intent of disrupting metastasis will require the specific targeting of molecular mechanisms involved in metastatic dissemination without disrupting normal migratory processes such as inflammation and wound healing [104].

The principle obstacle to developing therapy that specifically blocks metastasis is the time needed to determine therapeutic efficacy. Current anti-metastasis therapy is tested after first line therapy has failed or as an adjuvant to cytotoxic therapies. For many cancers these patients will remain disease free for several years thereby extending the duration of any trial and requiring a large number of patients. Patients subjected to anti-metastasis therapy will have to be under continuous treatment because it is currently not possible to predict when a cancer becomes metastatic. This chronic treatment compounds any negative side effects such as any impact on immunity or wound healing. Lastly, it currently not possible to predict if resistance to targeted therapy for motility would develop considering that thousands of molecular determinants are involved in the motility of tumor cells. The current objective is to design targeted therapies that disrupt molecular processes central and required in the motility of tumor cells. Consequently, all the drugs currently under consideration target not only motility but also influence cell viability and proliferation. Although currently no therapy targeting tumor cell motility has been approved for clinical use, several treatments are considered and are currently in clinical trials. Table VI provides a comprehensive representation of targeted therapies.

III. Future directions

In 2010 more than 1300 manuscripts were published on the topic of tumor cell migration and its contribution to metastasis (Fig. 1). Numerous molecular mechanisms involved in this complex process have been described and suggested as potential therapeutic targets, yet only a very small fraction have been evaluated clinically for their ability to limit metastasis, and none are in clinical use.

The difficulty of implementing motility-targeting therapeutics should not come entirely as a surprise considering the complications of determining therapeutic efficacy in the adjuvant setting with chronic treatment of cancer patients. This is further complicated by the central role of motility in normal physiology and therefore the need to determine metastasis-specific therapies. Nevertheless, the proof of principle has been presented several times in the form of reduced metastasis in preclinical animal models and promising results from clinical trials. These trails target Src, VEGF, EGF, and TGFβ which have broad biological impact and inhibit multiple mechanisms involved in cancer progression to maximize a favorable clinical outcome including the inhibition of both angiogenesis and metastasis or the inhibition of both tumor growth and motility..

Significant progress in the treatment of metastasis is expected to be made as therapies targeting specific migratory mechanisms such as SDF-1, c-MET, EpCAM, and Rho-kinase progress through their clinical evaluation (Table VI). The difficulty in confirming long-term suppression of metastasis will remain the main obstacle to successful clinical translation of any therapy targeting motility. To accelerate the evaluation of therapies that target metastasis, it may be necessary to take advantage of short, preoperative neoadjuvant trials and establish new short-term parameters of clinical success. These parameters could include the detection of changes in circulating tumor cells or a circulating metastasis biomarker.

The integrating function of scaffolding proteins is of particular interest because it brings together multiple molecular aspects of migration and is therefore less likely to fall subject to drug resistance. In addition, it is likely that combination therapies, targeting multiple mechanisms belonging to distinct principles presented here, will be developed to optimize efficacy and diminish drug resistance. In the past two decades many putative targets have been identified. If the first candidates, currently in clinical trials, prove successful, then this approach and a new class of targeted therapeutics will define the future of treating metastatic disease.

Acknowledgments

We want to recognize Kristin H. Kain for critical review of the manuscript. Trenis Palmer was supported by the National Institutes of Health under the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F31 National Cancer Institute). This work was partially supported by CCSRI Grant #700537 to JDL as well as NIH/NCI grant #CA120711-01A1 and CA143081-01 to AZ.

Abbreviations

- ALCAM

Activated Leukocyte Adhesion Molecule

- EMT

Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition

- RGD

Arg-Gly-Asp amino acid sequence

- TGFβ

Transforming Growth Factor beta

- HGF

Hepatocyte Growth Factor

- VEGF

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

- EGF

Epidermal Growth Factor

- SDF-1

Stromal cell Derived Factor -1

- TNFα

Tumor Necrosis Factors alpha

- EpCAM

Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule

- EphA2

Ephrin A2

- MMP

Matrix Metalloproteinase

- FAK

Focal Adhesion Kinase

- WAVE

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP)-family protein, WASP family Verprolin-homologous protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2010;60(5):277. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. PMID: 17982957816353055660related:rOOOLttMkPkJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz M, Yap A. Cell-to-cell contact and extracellular matrix. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18(5):461–2. PMID: doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302(5651):1704–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. PMID: 14657486; doi:10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedl P. Prespecification and plasticity: shifting mechanisms of cell migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16(1):14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.001. PMID: 15037300; doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedl P, Wolf K. Tumour-cell invasion and migration: diversity and escape mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(5):362–74. doi: 10.1038/nrc1075. PMID: 12724734; doi:10.1038/nrc1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rørth P. Collective guidance of collective cell migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(12):575–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.09.007. PMID: 17996447; doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bockhorn M, Jain RK, Munn LL. Active versus passive mechanisms in metastasis: do cancer cells crawl into vessels, or are they pushed? Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(5):444–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70140-7. PMID: 17466902; doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70140-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugino T, Kusakabe T, Hoshi N, Yamaguchi T, Kawaguchi T, Goodison S, Sekimata M, Homma Y, Suzuki T. An invasion-independent pathway of blood-borne metastasis: a new murine mammary tumor model. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(6):1973–80. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61147-9. PMID: 12057902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massagué J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(4):274–84. doi: 10.1038/nrc2622. PMID: 19308067; doi:10.1038/nrc2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward PM, Weiss L. Metachronous seeding of lymph node metastases in rats bearing the MT-100-TC mammary carcinoma: the effect of elective lymph node dissection. Breast Cancer Res Tr. 1989;14(3):315–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01806303. PMID: 2611404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sleeman J, Schmid A, Thiele W. Tumor lymphatics. Seminars in cancer biology. 2009;19(5):285–97. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.05.005. PMID: 19482087; doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weaver DL, Ashikaga T, Krag DN, Skelly JM, Anderson SJ, Harlow SP, Julian TB, Mamounas EP, Wolmark N. Effect of Occult Metastases on Survival in Node-Negative Breast Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008108. PMID: 21247310; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1008108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen DX, Massague J. Genetic determinants of cancer metastasis. Nature reviews Genetics. 2007;8(5):341–52. doi: 10.1038/nrg2101. PMID: 17440531; doi:10.1038/nrg2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the `seed and soil' hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):453–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. PMID: 12778135; doi:10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart IR, Fidler IJ. Role of organ selectivity in the determination of metastatic patterns of B16 melanoma. Cancer research. 1980;40(7):2281–7. PMID: 7388794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim M-Y, Oskarsson T, Acharyya S, Nguyen DX, Zhang XH-F, Norton L, Massagué J. Tumor self-seeding by circulating cancer cells. Cell. 2009;139(7):1315–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.025. PMID: 20064377; doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein CA. Parallel progression of primary tumours and metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(4):302–12. doi: 10.1038/nrc2627. PMID: 19308069; doi:10.1038/nrc2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feinberg AP. Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature. 2007;447(7143):433–40. doi: 10.1038/nature05919. PMID: 17522677; doi:10.1038/nature05919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119(6):1420–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. PMID: 19487818; doi:10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen DX, Massagué J. Genetic determinants of cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(5):341–52. doi: 10.1038/nrg2101. PMID: 17440531; doi:10.1038/nrg2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paget S. THE DISTRIBUTION OF SECONDARY GROWTHS IN CANCER OF THE BREAST. The Lancet. 1889 March;23:571–3. PMID. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss L. Metastasis of cancer: a conceptual history from antiquity to the 1990s. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2000;19(3–4):I–XI. 193–383. PMID: 11394186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mundy GR. Metastasis to bone: causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(8):584–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc867. PMID: 12154351; doi:10.1038/nrc867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen M, Louise Jones J. Jekyll and Hyde: the role of the microenvironment on the progression of cancer. J Pathol. 2011;223(2):162–76. doi: 10.1002/path.2803. PMID: 21125673; doi:10.1002/path.2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francia G, Emmenegger U, Kerbel R. Tumor-Associated Fibroblasts as “Trojan Horse” Mediators of Resistance to Anti-VEGF Therapy. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(1):3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.011. PMID: doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franco OE, Shaw AK, Strand DW, Hayward SW. Cancer associated fibroblasts in cancer pathogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21(1):33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.10.010. PMID: 19896548; doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peinado H, Lavothskin S, Lyden D. The secreted factors responsible for pre-metastatic niche formation: Old sayings and new thoughts. Seminars in cancer biology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.01.002. PMID: 21251983; doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ewing J. Neoplastic diseases. A treatise on tumors. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 1922 PMID: 13986938773706005348. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss L. Dynamic aspects of cancer cell populations in metastasis. Am J Pathol. 1979;97(3):601–8. PMID: 389067. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarin D, Vass AC, Kettlewell MG, Price JE. Absence of metastatic sequelae during long-term treatment of malignant ascites by peritoneo-venous shunting. A clinico-pathological report. Invasion Metastasis. 1984;4(1):1–12. PMID: 6735637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orr JA, Hamilton PW. Histone acetylation and chromatin pattern in cancer. A review. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 2007;29(1):17–31. PMID: 17375871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez-Paredes M, Esteller M. Cancer epigenetics reaches mainstream oncology. Nature Medicine. 2011;17(3):330–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2305. PMID: 21386836; doi:10.1038/nm.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Condeelis J, Pollard JW. Macrophages: obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell. 2006;124(2):263–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.007. PMID: 16439202; doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fingleton B. Molecular targets in metastasis: lessons from genomic approaches. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2007;4(3):211–21. PMID: 17878524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao D, Johnson RS. Hypoxia: a key regulator of angiogenesis in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(2):281–90. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9066-y. PMID: 17603752; doi:10.1007/s10555-007-9066-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan R, Graham CH. Hypoxia-driven selection of the metastatic phenotype. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(2):319–31. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9062-2. PMID: 17458507; doi:10.1007/s10555-007-9062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erler JT, Weaver VM. Three-dimensional context regulation of metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26(1):35–49. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9209-8. PMID: 18814043; doi:10.1007/s10585-008-9209-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar S, Weaver V. Mechanics, malignancy, and metastasis: The force journey of a tumor cell. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9173-4. PMID: 19153673; doi:10.1007/s10555-008-9173-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruppender NS, Merkel AR, Martin TJ, Mundy GR, Sterling JA, Guelcher SA. Matrix rigidity induces osteolytic gene expression of metastatic breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e15451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015451. PMID: 21085597; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sethi S, Macoska J, Chen W, Sarkar FH. Molecular signature of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in human prostate cancer bone metastasis. Am J Transl Res. 2010;3(1):90–9. PMID: 21139809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, Drobnjak M, Kakonen SM, Cordón-Cardo C, Guise TA, Massagué J. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(6):537–49. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00132-6. PMID: 12842083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, Bos PD, Shu W, Giri DD, Viale A, Olshen AB, Gerald WL, Massagué J. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436(7050):518–24. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. PMID: 16049480; doi:10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, Weinberg RA. Tumour invasion and metastasis initiated by microRNA-10b in breast cancer. Nature. 2007;449(7163):682. doi: 10.1038/nature06174. PMID: doi:doi:10.1038/nature06174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(1):9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. PMID: 20029421; doi:10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Craig SEL, Brady-Kalnay SM. Cancer cells cut homophilic cell adhesion molecules and run. Cancer Res. 2011;71(2):303–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2301. PMID: 21084269; doi:10.1158/0008-5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cavallaro U, Christofori G. Cell adhesion and signalling by cadherins and Ig-CAMs in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(2):118–32. doi: 10.1038/nrc1276. PMID: 14964308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu S, Calderwood DA, Ginsberg MH. Integrin cytoplasmic domain-binding proteins. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 20):3563–71. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.20.3563. PMID: 11017872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calderwood DA, Zent R, Grant R, Rees DJ, Hynes RO, Ginsberg MH. The Talin head domain binds to integrin beta subunit cytoplasmic tails and regulates integrin activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(40):28071–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28071. PMID: 10497155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25(1):9–34. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-7886-9. PMID: 16680569; doi:10.1007/s10555-006-7886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.López-Otín C, Matrisian LM. Emerging roles of proteases in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(10):800–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc2228. PMID: 17851543; doi:10.1038/nrc2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolf K, Wu YI, Liu Y, Geiger J, Tam E, Overall C, Stack MS, Friedl P. Multi-step pericellular proteolysis controls the transition from individual to collective cancer cell invasion. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(8):893–904. doi: 10.1038/ncb1616. PMID: 17618273; doi:10.1038/ncb1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark EA, Golub TR, Lander ES, Hynes RO. Genomic analysis of metastasis reveals an essential role for RhoC. Nature. 2000;406(6795):532–5. doi: 10.1038/35020106. PMID: 10952316; doi:10.1038/35020106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lämmermann T, Bader BL, Monkley SJ, Worbs T, Wedlich-Söldner R, Hirsch K, Keller M, Förster R, Critchley DR, Fässler R, Sixt M. Rapid leukocyte migration by integrin-independent flowing and squeezing. Nature. 2008;453(7191):51–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06887. PMID: 18451854; doi:10.1038/nature06887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parsons JT, Horwitz AR, Schwartz MA. Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(9):633–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm2957. PMID: 20729930; doi:10.1038/nrm2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aleshin A, Finn RS. SRC: a century of science brought to the clinic. Neoplasia. 2010;12(8):599–607. doi: 10.1593/neo.10328. PMID: 20689754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeatman TJ. A renaissance for SRC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(6):470–80. doi: 10.1038/nrc1366. PMID: 15170449; doi:10.1038/nrc1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. PMID: 9442882; doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kikyo M, Matozaki T, Kodama A, Kawabe H, Nakanishi H, Takai Y. Cell-cell adhesion-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of nectin-2delta, an immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecule at adherens junctions. Oncogene. 2000;19(35):4022–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203744. PMID: 10962558; doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abram CL, Courtneidge SA. Src family tyrosine kinases and growth factor signaling. Exp Cell Res. 2000;254(1):1–13. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4732. PMID: 10623460; doi:10.1006/excr.1999.4732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gallo R, Provenzano C, Carbone R, Di Fiore PP, Castellani L, Falcone G, Alemà S. Regulation of the tyrosine kinase substrate Eps8 expression by growth factors, v-Src and terminal differentiation. Oncogene. 1997;15(16):1929–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201344. PMID: 9365239; doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takenawa T, Miki H. WASP and WAVE family proteins: key molecules for rapid rearrangement of cortical actin filaments and cell movement. Journal of Cell Science. 2001;114(10):1801. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.10.1801. PMID. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarmiento C, Wang W, Dovas A, Yamaguchi H, Sidani M, El-Sibai M, DesMarais V, Holman HA, Kitchen S, Backer JM, Alberts A, Condeelis J. WASP family members and formin proteins coordinate regulation of cell protrusions in carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;180(6):1245–60. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708123. PMID: 18362183; doi:10.1083/jcb.200708123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117(7):927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. PMID: 15210113; doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Han H-J, Russo J, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 reprogrammes gene expression to promote breast tumour growth and metastasis. Nature. 2008;452(7184):187–93. doi: 10.1038/nature06781. PMID: 18337816; doi:10.1038/nature06781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nicoloso MS, Spizzo R, Shimizu M, Rossi S, Calin GA. MicroRNAs--the micro steering wheel of tumour metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(4):293–302. doi: 10.1038/nrc2619. PMID: 19262572; doi:10.1038/nrc2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Varambally S, Cao Q, Mani R-S, Shankar S, Wang X, Ateeq B, Laxman B, Cao X, Jing X, Ramnarayanan K, Brenner JC, Yu J, Kim JH, Han B, Tan P, Kumar-Sinha C, Lonigro RJ, Palanisamy N, Maher CA, Chinnaiyan AM. Genomic loss of microRNA-101 leads to overexpression of histone methyltransferase EZH2 in cancer. Science. 2008;322(5908):1695–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1165395. PMID: 19008416; doi:10.1126/science.1165395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]