Abstract

Context

The elimination of health disparities by race and ethnicity is a major public health goal for the US. This requires research establishing the reasons for disparities. This study explores racial-ethnic disparities in the patterns and trajectories of sexual risk-taking behaviors and STDs among young men.

Methods

The National Survey of Adolescent Males (NSAM), a nationally representative sample of men who self-reported on sexual behaviors and STDs (including biomarkers) during three survey waves at ages 15–19 (1988; n=1880), 18–22 (1990/1; n=1676), and 21–26 (1995; n=1377), are used to conduct descriptive and multinomial logistic regression analyses to test two hypotheses: that racial-ethnic differences in STDs are due to (1) the lower socioeconomic status, and (2) higher levels of risky sexual behavior among racial-ethnic minority groups.

Results

Black men report the highest sexual risk and STDs at each wave and across waves. Relative to white peers, Black and Latino men have higher odds of (1) maintaining high sexual risk and (2) increasing sexual risk over time. Both sexual risk behaviors and race-ethnicity predict STD outcomes. Race-ethnic disparities in STDs remain after controlling for sociodemographic variables. Further, disparities also persist when level of risky sexual behavior is controlled.

Conclusions

Race-ethnicity continues to differentiate black and Latino young men from white peers in terms of STDs. Development of HIV/STD prevention programs targeting different racial-ethnic subgroups of adolescent men and addressing both individual- and contextual-level factors are needed to curb STD spread.

BACKGROUND

The elimination of health disparities by race and ethnicity is a major public health goal for the United States (1). In order to accomplish this goal, it is essential that research establish what the underlying reasons for the disparities are, because the policies and interventions we enact to combat disparities should differ depending upon what causes them. Disparities by race or ethnicity may be spurious and due, in part or wholly, to the strong association between being a member of a minority group and lower socioeconomic status. Or, they may emerge because individual members of different groups engage in risky health behaviors at different rates. In the U.S. sociodemographic variables (e.g., age, region, mother's education, behind in school, and family structure at age 14) and behavioral variables (age at first sex) are known to be associated with sexual risk taking behaviors (2–4).

Our focus in this paper is racial and ethnic disparities in sexually transmitted diseases (STD) among adolescents and young adults, which are substantial. Sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, among teenage and young adult men and women cause significant public health and social costs annually in the U.S. Chlamydia and gonorrhea rates are the highest STD rates among 15–24 year olds (5, 6). Approximately 18.9 million new STD cases occur annually, of which half occur in sexually active young people aged 15–24 who only constitute one-fourth of the sexually active population (7).

There is notable racial-ethnic disparity in STD prevalence. According to the CDC, in 2007 the Chlamydia rate among young black men ages 20–24 was four times greater than among their Latino peers and eight times greater than their white peers; half of all Chlamydia and Syphilis cases and 70% of Gonorrhea cases occurred among young black men and women (8). Paradoxically, black youth are more likely to use condoms than their Latino and white peers (9–14). Specific to the first sexual encounter (9–14), the percent of condom use among young black men increased from 61% in 1995 to 85% in 2002 whereas during the same time Latino peers reported a smaller increase (55% to 67%) and white peers experienced a decrease (76 to 68%). And, in 2007 black male high school students reported higher condom use at last sexual intercourse (74%) than white males (66%) (15). Yet, black youth – compared to their Latino and white peers – continue to experience disproportionately higher STD rates (16). Disease reporting and variability by race-ethnicity in access to care and treatment, however, do not seem to account for these disparities, as indicated by a nationally representative survey (17). The fact remains that STD cases are preventable if we can understand factors contributing to these cases.

Understanding factors that influence STD risk among young men is crucial for developing informed prevention programs to reduce infection incidence and prevalence rates. Numerous studies have explored how individual behaviors contribute to increased STD risk, including age at first sex (18), same sex partnerships (MSM: Men who have Sex with Men) (19), alcohol and substance use (20), multiple sexual partners (21, 22), risky sexual partners (23), and inconsistent condom use (24). These individual STD risk behaviors are different among racial and ethnic groups. For example the 2007 national Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS), which consists of public and private school students in grades 9 -12, indicate that risky sexual behaviors are frequent among black and Latino male students compared to white male students (25). Specifically, the prevalence of ever having sexual intercourse was 73% among black males, 58% among Latino males, and 44% among white males. A larger percentage of black male students reported having more than four sexual partners in their lifetime (38%) than did Latino male students (23%) and white male students (12%). This may be a result of earlier sexual debut as indicated by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reporting that 26% of black males had sex before the age of 13 compared of 12% Latino males and 6% of white males, increasing the window of risk exposure for black youth relative to their Latino and white peers (25). Although blacks report more sexual partners with age and basic demographics controlled, this difference is largely explained by years since sexual debut, which at any given age is higher for blacks due to earlier age at first sex (26).

Racial-ethnic differences in patterns* and trajectories** of sexual risk behaviors may also contribute to the observed disparities in STD risk. One specific pattern involves concurrent partnerships defined by having more than one active sexual partnership in overlapping time periods. According to the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, three times more black men relative to white men reported having at least one concurrent sexual partnership within the last year (27). Concurrency, in turn, has been implicated as a risk factor associated with STD risk (28) and a contributor to the rapid transmission of STD within sexual networks (29). In terms of trajectories, cumulative risky sexual behavior increases a person's exposure to and likelihood of acquiring STDs. Even if the risk is considered small for each act, consistently engaging in those acts over time substantially increases risk (30).

Our goal is to investigate the reasons for racial-ethnic health disparities by examining detailed data on sexual behavior and STDs from a nationally representative, longitudinal sample of American men that were collected as men matured from the late teenage years to their early to mid 20s. More specifically, the aims comprise the testing of two specific hypotheses: 1) that racial and ethnic health disparities in STDs are due to the association of ethnic minority status with lower socioeconomic status--and thus actually reflect socioeconomic health disparities; and 2) that any disparities in STDs left unaccounted for by socioeconomic factors can be partially or fully explained by race-ethnic differences in risky sexual behavior.

METHODS

Data

The National Survey of Adolescent Males (NSAM), described in detail elsewhere (31; see also 32), is a longitudinal survey exploring the sexual relationships, contraceptive practices, and sexually transmitted disease knowledge and attitudes of men from adolescence into young adulthood. The most sensitive data – same-sex experiences, illicit drug use – were collected via self-administered questionnaires and non-sensitive questions were asked during the face-to-face portion of the in-home interview. During the first wave (1988) of the study, 1,880 nationally representative non-institutionalized unmarried men ages 15 to 19 living in the conterminous United States were interviewed. Black and Latino young men were oversampled. NSAM participants were followed up for the first time in wave 2 (ages 17–22; 1990/1; N=1,676) and for a second time in wave 3 (ages 21–26; 1995; N=1,377). In addition to the in-home survey, men were asked to provide urine samples in wave 3 (33). Across the three waves this study has a 75 percent response rate; (for more detailed information about these data, please refer to 31 and 32). Longitudinal weights are used to adjust for non-response. We used all available data across all three waves in our cluster analysis (see 30). Our sample consisted of 36 percent black, 40 percent white, 21 percent Latino, and 3 percent other racial/ ethnic men in the first wave (unweighted) and men averaged 17 years old.

These data have four compelling advantages for examining the questions we pose. First, the data on individual behavior are extensive and, as we have previously demonstrated (30) reveal that there are distinct patterns underlying men's sexual behavior as they mature from adolescents to adults and that both the high risk patterns themselves as well as high risk trajectories of behavior are associated with STDs. This enables us to examine the degree to which the higher rates of STDs among black and Latino men are due to differences in these behaviors and trajectories of behavior. Second, the fact that the data are a nationally representative sample insures that we are able to assess racial and ethnic differences net of a broad array of socioeconomic controls. This ensures that when our analysis uncovers racial or ethnic differences we can more confidently (although not perfectly) conclude that they are not due to the fact that black and Latino men in the US often come from disadvantaged social origins. Third, while some of the data we use are self-report, we also have a clinical indicator of Chlamydia infection that was determined from a urine test. Fourth, according to HIV and STD-related risk taking behavior research, sexual risk taking behaviors (e.g., numerous partners) start in adolescence, peak in late adolescence, and decline in early adulthood when men's professional and personal lives stabilize (34, 35). Therefore, the developmental period—the transition to adulthood—that the data collection period covers is one that is particularly salient for the examination of STD.

Measures

Sexually Transmitted Disease

We created a measure of `ever diagnosed with an STD' for each wave taking into account a respondent's self-reports for that wave and previous waves. For the multivariate analysis, we combine ever STD by wave into a single indicator of whether or not respondents report having an STD in any of the three waves. Specific to wave 3 two additional STD measures were collected: respondents reported whether they had been diagnosed with an STD within the past 12 months and urine samples were tested for Chlamydia. (Refer to 30 for more detailed information).

Race-Ethnicity

Respondents began by reporting whether or not they considered themselves Latino or of Spanish origin/descent. This was followed-up by a question about which Latino/ Spanish origin/descent category best characterized them. Respondents were then asked which race they considered themselves with four close-ended responses (black, white, American Indian/ Alaska Native, Asian/ Pacific Islander) and one open-ended response whereby they specified their race. We recoded these responses into four categories – Latino, non-Latino black, non-Latino white, and other.

Sociodemographic Measures

We include whether the respondent's mother was a teenager at her first birth (yes/no), the respondent's age, family structure at age 14 (both biological parents, one biological parent, both a biological and step parent, no biological parents), whether the respondent repeated an academic grade or was held behind a year (yes/ no), the respondent's mother's highest level of education, and region of the country in which the respondent lived.

Age at First Sex and Sexual Risk Behavior Clusters and Trajectories

Respondents who reported they ever had sexual intercourse with a female were asked how old they were the first time they had sexual intercourse. Additionally, this study builds on previous work establishing that young men's sexual risk behavior can be distinguished by membership in five distinct clusters (see 30 for details about the cluster analysis) and further distinguished by distinct trajectories of risk through the late adolescent and early adult years. For 15–19 year olds in 1988 there are three distinct clusters that are low risk: “no heterosexual sex” defined by zero female partners and no condom use, “low risk – high protection” defined by 1.4 female sexual partners in the last year and 85% condom use, and “low risk – low protection” defined by 1.7 female sexual partners in the last year and 7% condom use. There are two high risk clusters. One called “risky partners – high protection” is defined by 1.1 risky partners, 1.9 total female sexual partners in the last year, and 83% condom use, and another called “many partners – some protection” defined by 7.4 female sexual partners in the last year, 7.5 months in the last year with two or more female sexual partners, and 39% condom use.

We characterize each man as exhibiting one of five sexual risk behavior trajectories depending on whether his cluster membership was: 1) consistently “low risk” across all three waves (“ steady low risk”); 2) consistently “high risk” across all three waves (“ steady high risk”); 3) started out in a “low risk” cluster and ended up in a “high risk” cluster by wave 3 (“upward risk”); started out in a “high risk” cluster and ended up in a “low risk” cluster by wave 3 (“downward risk”); started and ended “low risk” with a peak to “high risk” in wave 2 (“peak high risk”).

Analyses

We begin by documenting substantial racial-ethnic disparities in STDs during adolescence and early adulthood. We next perform descriptive analyses to establish the plausibility of an explanation for racial and ethnic disparities in STDs that attributes the disparities, in whole or in part, to differences in individual behavior. To this end, we examine racial and ethnic variation in high risk sexual behavior and high risk trajectories of sexual behavior utilizing the indicators we explicated in the previous section. We use univariate parametric (Analysis of Variance) statistical tests with follow-up Tukey adjusted pairwise comparisons to determine whether or not our estimates of membership in the various risk groups were significantly different from one race-ethnicity to another.

In our multivariate models, we take into consideration an extensive set of control variables that include family background factors (i.e. region of residence in adolescence, mother's education, family structure at age 14), and individual characteristics (i.e. being behind in school, age at first sex). This step is crucial, since, as we noted above, one major explanation for racial ethnic health disparities is that they actually reflect socioeconomic health disparities. Finally, we provide evidence that it is plausible that these disparities are associated with differences across racial-ethnic groups in levels of risky sexual behavior using multinomial logistic regression. Analyses reported in this paper were generated using SAS 9.1.

RESULTS

Table 1 contains weighted distributions of all variables in the analysis by survey wave. When we use the weights, nearly 15 percent of the sample identify as black, 75 percent as white, and 10 percent at Latino in each wave. At wave 1 the average age of respondents is 16.9 years with 19 year olds having the least (16%) and 18 year olds having the most (23%) representation. The average age of first sex is 16 years old in each wave. Between 44 and 47 percent of respondents report their mothers were teenagers at their first birth and their mother's education averaged one year more than high school. For each wave over 70 percent of respondents lived with both biological parents at age 14 and 2.5 percent or less lived with neither parent. Between 29 and 31 percent reported having repeated a grade by the first wave and 11–12 percent reported during wave 2 they were held behind in school. In wave 1, most respondents lived in the south (37%). The percent of respondents reporting ever being told they had an STD by a health professional increased from 2 percent in wave 1 to 12 percent in wave 3. Reports of recently being diagnosed are 1 percent and testing positive for Chlamydia are 4 percent.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics

| Demographic Characteristics | Wave 1 Weighted (N=1,880) | Wave 2 Weighted (N=1,676) | Wave 3 Weighted (N=l,377) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race-Ethnicity (%) | |||

| Black | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.1 |

| White | 74.6 | 74.7 | 74.4 |

| Latino | 10.4 | 10.3 | 10.5 |

| Age at Wave 1 (%) | |||

| 15 | 20.1 | 20.1 | 20.1 |

| 16 | 19.0 | 19.6 | 19.6 |

| 17 | 22.5 | 21.8 | 21.8 |

| 18 | 22.9 | 23.4 | 23.4 |

| 19 | 15.5 | 15.1 | 15.1 |

| Age at First Sex | 15.8 | 15.9 | 16.0 |

| Mom's characteristics | |||

| Teenage mother (%) | 46.4 | 46.0 | 44.3 |

| Education (mean) | 12.9 | 13.1 | 12.9 |

| Living arrangements at age 14 | |||

| Both parents | 70.5 | 70.0 | 71.0 |

| One biological parent | 17.4 | 17.7 | 18.2 |

| One biological parent + stepparent | 9.7 | 9.8 | 9.3 |

| Neither biological parent | 2.4 | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| School difficulties | |||

| Repeated a grade by 1988 | 30.1 | 30.7 | 28.5 |

| Behind in School (1990) | -- | 12.1 | 10.5 |

| Region (1988survey year data) | |||

| North | 19.0 | 19.0 | 18.7 |

| South | 37.2 | 37.4 | 37.6 |

| Midwest | 23.7 | 23.7 | 24.2 |

| West | 20.1 | 19.9 | 19.6 |

| STD measures (%) | |||

| Ever Had an STD | 1.7 | 6.6 | 11.5 |

| Diagnosed STD in the past year | --- | --- | 1.3 |

| Positive chlamydia test | --- | --- | 3.6 |

Sexual Risk Cluster Patterns and STDs by Race-Ethnicity and Wave

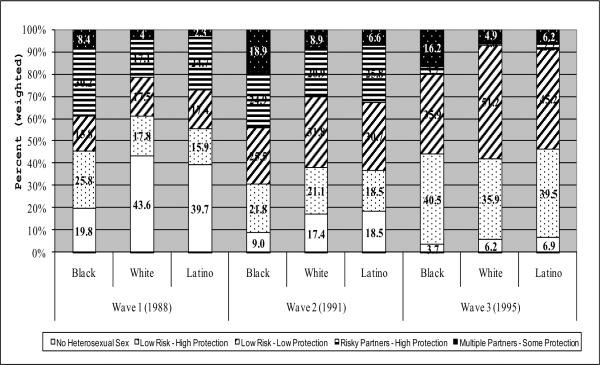

As depicted in Figure 1, in each wave young black men are less likely than others to be members of the “no heterosexual sex” cluster. Furthermore, black youth are over-represented in “multiple partners – some protection,” the highest risk cluster (30) – across all three waves with nearly one in five black men belonging to this cluster in wave 2. Although membership in this high risk cluster increased for all three racial-ethnic groups from wave 1 to wave 2, only black and Latino youth maintain a high proportion in wave 3. Lastly, when comparing membership in the two low risk groups (low-risk-low protection vs low-risk high protection), black men are more likely to be in the low risk - high protection group in each wave compared to their white and Latino peers, who are more likely to be in the low risk – low protection cluster in each wave. Condom use decreases within long-term relationships and with age (36). The pronounced larger membership in low-risk high-protection among black youth may be the result of black youth taking longer to establish long-term monogamous sexual relationships than their white and Latino peers and / or a lack of trust in sexual partners being STD-free and/ or faithful either by themselves or their female partners.

Figure 1.

Sexual Risk-Taking Cluster by Race-Ethnicity and Wave - Weighted Percents

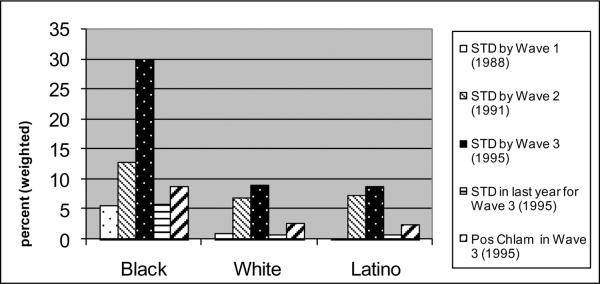

Figure 2 illustrates the racial and ethnic differences in STDs that we observe in our data, based on all men who completed each wave (1,880 for wave 1, 1676 for wave 2, and 1,377 for wave 2). The figure shows that, across all five measures of STD (ever STD by each wave, STD in the last year in 1995, and Chlamydia test in 1995), black men exhibit higher levels than either white or Latino men, while there are no disparities between Latino and white men. By wave 3 one in three black men report having been told by a doctor that they had an STD, over 5 percent report having an STD within the past year, and nearly 10 percent tested positive for Chlamydia. STD reports for white and Latino men are nearly identical to one another and starkly lower compared to black men: less than 9 percent for ever having an STD, less than 1 percent having an STD in the past year, and less than 3 percent testing positive for Chlamydia. Now we turn to analyses limited to men who completed all three waves of data collection (N=1,290).

Figure 2.

Sexually Transmitted Disease Experience by Wave and Race-Ethnicity

Sexual Risk Cluster Trajectories, and STD Outcomes across Waves, by Race-Ethnicity

Differences in socioeconomic status by race-ethnicity are well known and we regard our first hypothesis as plausible based on these well known differences (37, 38). Our second hypothesis, however, requires some justification. In Table 2 where the five sexual risk longitudinal trajectories are presented by race-ethnicity, we show racial-ethnic disparities in sexual risk behaviors among the three groups with the two minority groups having higher risk trajectories. Black men are more likely to maintain high sexual risk across all three waves relative to white and Latino men: 9% for black men, less than 2% for white men, and 4% for Latino men. One of the most striking finding is that “Steady Low Risk” is the largest trajectory across all three race-ethnicities (Table 2); the racial-ethnic groups, however, differ in terms of how “normative” this group is. White and Latino men are more likely to maintain membership in low sexual risk clusters across all three waves relative to black men: 54% for white men, 49% for Latino men, and 33% for black men. “Downward Risk” rivals “Steady Low Risk” as the largest group for black men, with less than three percentage points difference.

Table 2.

Sexual Risk Stability and Change by Race-Ethnicity - Frequencies and Weighted Percents

| Risk Trajectory | Black | White | Latino | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Wt. % | N | Wt. % | N | Wt. % | |

| Steady Low Risk | 127 | 32.5a | 299 | 53.8b | 135 | 49.3b |

| Peak High Risk | 91 | 17.8 | 103 | 18.5 | 42 | 15.3 |

| Downward Risk | 137 | 29.8a | 117 | 21b | 63 | 23.0ab |

| Upward Risk | 54 | 10.7a | 24 | 4.3b | 23 | 8.4ab |

| Steady High Risk | 51 | 9.2a | 13 | 2.3b | 11 | 4.0b |

| Total | 460 | 15.1 | 556 | 74.4 | 274 | 10.5 |

Note: Within rows, race-ethnicity weighted percent columns with different superscripts are statistically significantly different from one another with Tukey adjustments for multiple tests.

Of course, these differences in sexual behavior, like differences in the STD outcomes, may reflect socioeconomic disparities, rather than true racial-ethnic disparities. Table 3, however, shows that this is not the case. In this table we present evidence that, even after controlling for our socioeconomic controls, both black and Latino men are more likely to be in the higher risk trajectory groups than in the steady low risk group relative to white peers. Nearly one-third of black men have never been in a high sexual risk group (they maintain steady low risk); yet, another third report high sexual risk group membership for at least two waves (results not shown). By comparison, the percent of men reporting high sexual risk for at least two waves is 14.5 for white men and 15.1 for Latino men. These sexual behavior trajectory distributions by race-ethnicity (Table 2) provide a context for the STD outcomes shown in Figure 2. STD experience, be it ever by wave 3, within the past year, or a positive Chlamydia urine test, is disproportionately highly reported by black men. Black men report disproportionately higher sexual risk exposure in and across early adolescence (wave 1), late adolescence (wave 2), and early adulthood (wave 3). Hence, higher sexual risk behavior may account, at least in part, for higher STD reports among black men.

Table 3.

Multinomial Logistic Regression by Race-Ethnicity and of Sexual Risk Trajectories

| Race-Ethnicity | Risk Trajectory | Odds (CI) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Black | Steady High Risk | 1.9*** (1.3–2.8) |

| Peak High Risk | 1.2+ (0.98–1.5) | |

| Downward Risk | 1.2+ (0.97–1.5) | |

| Upward Risk | 1.8*** (1.4–2.5) | |

| Latino | Steady High Risk | 1.7* (1.1–2.7) |

| Peak High Risk | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | |

| Downward Risk | 1.3*(1.03–1.7) | |

| Upward Risk | 1.7** (1.2–2.4) | |

Note: Results for a model in which teen mother status, mother's highest education, age, living arrangements at age 14, repeated a grade in Wave 1, held behind in school, and region of the country are controlled.

Note: Reference groups are White men, steady low risk.

Note: Sample size = 1,290.

Note:

p<0.1,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Race-Ethnicity Continues to Predict Sexual Risk Cluster Trajectories

In Table 4 we present the results of the test of our two hypotheses. In this table we examine three outcomes: ever STD (in any wave), STD in the past year measured as of 1995, and a positive Chlamydia test in 1995. In Model 1 for each of the three outcomes, we present evidence that, even after a fairly extensive set of socioeconomic factors are controlled, black men are more likely than white men to have an STD, although this is not true for Latino men (which seemed clear from Figure 1 as we discussed above). In Model 2 for each outcome, we show that this disparity is not completely due to differences between black and white men in risky sexual behavior, given the estimates of the odds ratios for black men do not diminish substantially and remain positive and statistically different from 0. Depending on the STD outcome, relative to white peers, black men have a 2.9 to 4.1 higher odds of reporting STD outcomes. It is important to note that the sexual behavior trajectories do affect STD outcomes, as we have shown before, so their failure to substantially reduce racial disparities is not because they are not themselves associated with STD outcomes. Relative to Steady Low Risk, Downward Risk and Steady High Risk are associated with higher odds (2.0 and 2.9, respectively) of ever reporting being diagnosed with an STD. These findings support the conclusion that both race-ethnicity and sexual risk behaviors (in this case, starting out with high sexual risk at wave 1 and either persisting until wave 3 or dropping to low risk by wave 3) predict ever having an STD into early adulthood (wave 3).

Table 4.

Logistic Regression of Race and Trajectory on STD Outcomes

| Variables | STD ever (N=1096) | STD last year (N=1010) | Positive Chlamydia (N=1093) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Odds (CI) | Odds (CI) | Odds (CI) | Odds (CI) | Odds (CI) | Odds (CI) | |

| Black | 3.2*** (2.2–4.9) | 2.9*** (1.9–4.3) | 5.0** (1.7–14.3) | 4.0* (1.3–12.0) | 4.1*** (1.9–9.0) | 4.1*** (1.8–9.0) |

| Latino | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) | 2.2 (0.5–8.7) | 1.8 (0.4–7.4) | 2.2 (0.9–5.7) | 2.2 (0.9–5.7) |

| Age at first sex | 1.2*** (1.1–1.2) | 1.1*** (1.1–1.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| Teen mother | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 0.4* (0.1–0.9) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) |

| Age in years | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.5** (1.1–2.0) | 1.5** (1.1–2.1) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

| Live with one bio parent | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 1.2 (0.5–2.9) | 1.2 (0.5–3.2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) |

| Live with one bio and one step parent | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 1.0 (0.3–3.6) | 0.9 (0.2–3.2) | 1.6 (0.5–5.5) | 1.6 (0.5–5.5) |

| Lives with no parents | 1.4 (0.5–4.0) | 1.4 (0.5–4.0) | 0.2 (0.1–0.8) | 0.2* (0.0–0.7) | 0.9 (0.2–4.1) | 0.9 (0.2–4.2) |

| Repeated a Year | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | 1.2 (0.7–2.3) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) |

| Behind a year in school | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) | 0.3 (0.1–1.0) | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) |

| Mom's highest education | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| Northeast | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) | 1.8 (0.6–5.4) | 2.1 (0.7–6.9) | 1.9 (0.8–4.6) | 1.9 (0.8–4.6) |

| Midwest | 0.8 (0.6–1.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 2.4 (0.8–7.3) | 2.1 (0.7–6.6) | 1.3 (0.6–2.9) | 1.3 (0.6–2.9) |

| West | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 6.8 (0.8–54.4) | 8.5 (1.0–74.2) | 1.0 (0.4–2.3) | 1.0 (0.4–2.4) |

| Steady High Risk | 2.9*** (1.5–5.5) | 4.1 (0.9–18.3) | 1.2 (0.4–3.2) | |||

| Peak Risk | 1.4 (0.7–2.6) | 3.1 (0.6–15.5) | 1.4 (0.5–3.9) | |||

| Downward Risk | 2.0* (1.1–3.7) | 1.5 (0.4–5.4) | 1.6 (0.6–4.4) | |||

| Upward Risk | 0.9 (0.4–1.8) | 0.2* (0.1–0.9) | 1.3 (0.4–4.3) | |||

Note: Sample sizes differ for each outcome based on whether a respondent was sexually experienced and completed the STD measures.

Note:

p<0.1,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

In Table 5 we further explore the finding that sexual behaviors do not fully mediate the relationship between race-ethnicity and STD outcomes. We show that, within each category of risk trajectory, black men are more likely to report or test positive for an STD than white men. Of particular note in Table 5 is the finding that even among men who report steady low risk sexual behavior, black men are more likely than white or Latino men to report STDs.

Table 5.

STD and Sexual Risk Stability and Change by Race-Ethnicity - Weighted Percents

| Risk Trajectory | Black (N=460) | White (N=556) | Latino (N=274) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STD ever | STD last year | Pos. Chl. | STD ever | STD last year | Pos. Chl. | STD ever | STD last year | Pos. Chl. | |

| Wt. % | Wt. % | Wt. % | Wt. % | Wt. % | Wt. % | Wt. % | Wt. % | Wt. % | |

| Steady Low Risk | 18.8a | 1.4 | 9.6a | 5.1b | 0.8 | 4.2b | 4.6ab | 0.4 | 2.2ab |

| Peak High Risk | 27.7 | 3.4 | 7.4a | 17.1 | 0.2 | 0.2b | 19.0 | 0.9 | 1.0ab |

| Downward Risk | 29.6a | 6.7a | 6.1a | 6.8b | 0b | 0.7b | 6.1b | 0b | 2.4ab |

| Upward Risk | 43.8a | 19.0a | 9.7 | 18.8b | 1.9b | 5.9 | 16.8ab | 2.7ab | 8.6 |

| Steady High Risk | 47.7a | 5.9 | 15.5 | 16.2b | 0 | 0 | 13.5b | 9.6 | 0 |

| Total | 28.9a | 5.5a | 8.7a | 8.4b | 0.6b | 2.7b | 8b | 0.7b | 2.4b |

Note: Within risk trajectory and STD outcome, race-ethnicity weighted percent columns with different superscripts are statistically significantly different from one another with Tukey adjustments for multiple tests.

DISCUSSION

In this study we address well-known racial-ethnic disparities in STDs among adolescent or young adult men in the U.S wherein ethnic minorities exhibit higher levels of STD than whites. In a large, nationally representative dataset we observe these disparities and test two hypotheses regarding the origins of these disparities. Specifically we test first, whether or not there is evidence that they are actually socioeconomic disparities, and second, whether or not they are due, in part or in whole, to differences in risky sexual behavior.

Even after controlling for sociodemographic variables, age at first sex, grade retention, being behind in school, and sexual risk behavior trajectories, race-ethnicity continues to predict whether or not a man reports ever having an STD by wave 3, an STD in the last year (in wave 3), and testing positive for Chlamydia (wave 3). Disparities between black and white young men persist. Moreover, although we present evidence that black and Latino young men do exhibit higher levels of risk sexual behavior relative to white peers (consistent with previous findings; 25, 27, 28), controlling for these behaviors does not substantially change the association between being black and STDs. In fact, we observe very high levels of disparities between black and white young men, even within groups that have very low levels of risky behavior.

What is causing these disparities? We speculate that important aspects of the social context might be one avenue for further research to explore. In particular, we point out that the relatively high levels of STD prevalence that the data we present here document might themselves be responsible, given that women and men tend to have sex with people who share their social and demographic characteristics. If people select their partners from within their own racial-ethnic groups, and one group has a higher level of STDs than another, it is axiomatic that regardless of behavior, members of this group will be at higher risk. The mating pool for young black men may have a higher STD prevalence rate than the mating pools for their Latino and white peers. This may explain our finding that 20 percent of black men reporting “steady low risk” also report ever having an STD, a higher percent than for white and Latino men who report “steady high risk.” In other words, differences in exposure to the risk of infection linked to differences in the social and physical environments, not just differential behavior, may place some teens and young adults at higher risk. Policies and program interventions to combat disparities that respond to environmental or network differences would be quite different from those that aim to change behaviors. Future research would benefit from examining the romantic and sexual networks of young men to assess the degree to which these networks predict STD outcomes above and beyond sexual behaviors, sexual debut, and race-ethnicity. Knowing the STD/ HIV prevalence rates of Census tracts as well as the male to female ratio (gender ratio imbalances) within these tracts may help disentangle the unmeasured variance being assumed by race-ethnicity.

Furthermore, mapping the density and availability of sexual and reproductive health services as well as pharmacies and drug stores that carry condoms (male and female) in Census tracts may provide insight into whether race-ethnic disparities exist for STD prevention and treatment. If racial or ethnic disparities exist in access to condoms, these may explain why black men report higher sexual risk taking and STD outcomes and would provide insights into a different and effective preventive strategy.

Implications and Future Directions

The contribution of this study to the literature is that even after controlling for sociodemographic variables known to be associated with race-ethnic differences in sexual risk-taking behaviors and STD outcomes, including age of sexual debut, race-ethnicity continues to predict sexual risk trajectories and STD outcomes. Young black men appear doubly burdened: 1) their behaviors are more risky, and 2) other factors, perhaps contextual, put them at heightened risk for STD outcomes even when their behavior is not risky. These results corroborate a growing body of literature which posits that individual-level risk behaviors do not alone account for race-ethnicity disparities in STI prevalence and incidence. In fact, network-level factors, such as concurrent sexual partnerships (39) and sexual mixing patterns (40), may account for observed STI disparities by race-ethnicity (41, 42). The implications of this finding are important given the past and current strategy for achieving positive sexual and reproductive health is minimal exposure to and engagement in sexual risk behaviors. Steady low sexual risk for Black men, compared to steady low sexual risk for white and Latino men, is not as effective in preventing STD outcomes even if the outcomes are lower relative to their Black peers who engage in higher sexual risk. Minimizing sexual risk behaviors does matter. There has been a remarkable increase in the use of condoms, primarily as a single method of protection, among teenagers in the US since 1988 (9, 10, 12–14). Yet, STD incidence among youth is increasing at a faster pace. However, interventions focusing only on individual-level factors have had limited success in curbing STD disparities (43, 44). Development of STD prevention programs needs to recognize that STD transmission is not simply influenced by one's own risk behaviors, but also by the risk of one's sexual partners (45).

Measurement error is also an issue. Youth may report more condom use while not properly using condoms during all forms of sexual activity (including oral sex). Intervention and prevention strategies need to cover topics of how to use condoms effectively and consistently whenever engaging in any type of sex. Likewise, items in research studies assessing only whether a condom was ever used, used at last intercourse, or at first intercourse are not sufficient in describing true sexual risk and exposure to STDs.

Limitations and Strengths

One of the most obvious limitations of this study is that the findings are limited to young men and cannot be generalized to young women. Much past research has been conducted on women. One way to include women in a study of sexual risk behaviors and STD outcomes is to examine sexual networks of men, noted above as a possible future direction. Another limitation is that although we used as many variables as possible to capture socioeconomic status in youth, our measures of current socioeconomic status are limited. Our race-ethnicity variable may be accounting for variance typically accounted for by unavailable measures of socioeconomic status. Longitudinal data is both an asset and a challenge. It provides the opportunity to examine change and stability over developmental stages and the approach we used went beyond the individual to examine clusters and cluster trajectories. Attrition poses serious selection concerns and power issues for which sampling, design, and attrition weights can only partially adjust. Stratifying by race-ethnicity further reduces cell sizes for analyzing differences by race-ethnicity and sexual risk group. The benefit of NSAM data, however, is the oversampling of minority men. This enabled us to examine differential trends in sexual risk by race-ethnicity for each wave, across waves, and to link these trends to STD outcomes for all three racial-ethnic groups. We are confident that these findings will spark future research exploring the mechanisms by which race-ethnicity predicts these differences above and beyond sociodemographic characteristics. Several contextual mechanisms are discussed above. Modeling mechanisms will move the field forward in terms of STD prevention and interventions efforts.

Even though the most recent round of data were collected in 1995, these 21 to 26 year old men resemble same-aged NSFG 2002 male respondents in terms of sexual risk taking variables used in the creation of the clusters (30). Furthermore, with the forthcoming wave of NSAM, the exploration of sexual risk taking trajectories by race-ethnicity can be extended beyond young adulthood to middle adulthood and to other outcomes in later life. NSAM data continue to serve as the only longitudinal data set examining men's sexual and reproductive behaviors and HIV risk factors in this degree of depth. The measures collected, including urine samples for clinical STD testing, remain unparalleled by other data and continue to offer opportunity for innovative models of men's behaviors and outcomes. Data collection for the forthcoming fourth wave of NSAM data is currently underway and will end in late 2010. These data will become available for analysis in mid 2011.

Conclusion

We discovered that both sexual risk behaviors and race-ethnicity predict STD outcomes. Our findings demonstrate that in order to assess potential factors for which race-ethnicity serves as a proxy, future research needs to examine contextual factors in addition to sexual risk behavior trajectories. Exploring these additional factors will help to identify effective strategies for reducing race-ethnic disparities in HIV and STD risk among young men.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 HD036948).

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2020 Framework. Last retrieved from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/HP2020/Objectives/framework.aspx on April 20, 2010.

- 2.Harvey SM, Spigner C. Factors associated with sexual behavior among adolescents: A multivariate analysis. Adolescence. 1995;30(118):253–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luster T, Small SA. Factors Associated with Sexual Risk-Taking Behaviors among Adolescents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1994;56(3):622–632. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Small SA, Luster T. Adolescent Sexual Activity: An Ecological, Risk-Factor Approach. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1994;56(1):181–192. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine - Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Diseases . In: Hidden epidemic: confronting sexually transmitted diseases. Eng TR, Butler WT, editors. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller WC, Ford CA, Morris M, et al. Prevalence of chlamydial and gonococcal infections among young adults in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(18):2229–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.18.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;6(1):6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2007. Jan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abma J, Sonenstein FL. Vital Health Statistics. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, Md: 2001. Sexual Activity and Contraceptive Practices among Teenagers in the United States, 1988 and 1995. 23(21) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alan Guttmacher Institute Facts on Young Men's Sexual and Reproductive Health. In Brief. 2008 June; Last retrieved from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_YMSRH.pdf on May 10, 2010.

- 11.Anderson JE, Wilson R, Doll L, Jones TS, Barker P. Condom Use and HIV Risk Behaviors Among U.S. Adults: Data from a National Survey. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31(1):24–28. 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Developing Healthy People 2020: Family Planning. Last retrieved from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/HP2020/Objectives/ViewObjective.aspx?Id=259&TopicArea=Family+Planning&Objective=FP+HP2020%e2%80%9310&TopicAreaId=21 on October 30, 2009.

- 13.Ku L, Sonenstein FL, Pleck JH. The dynamics of young men's condom use during and across relationships. Family Planning Perspectives. 1994;26(6):246–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonenstein FL, Ku L, Lindberg LD, Turner CF, Pleck JH. Changes in sexual behavior and condom use among teenaged males: 1988–95. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(6):956–59. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2007. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(SS-4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2008. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: Nov, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datta SD, Sternberg M, Johnson RE, Berman S, Papp JR, McQuillan G, et al. Gonorrhea and chlamydia in the United States among persons 14 to 39 years of age, 1999 to 2002. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147(2):89–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Upchurch DM, Mason WM, Kusunoki Y, Johnson M. Social and behavioral determinants of self-reported STI among adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(6):276–287. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.276.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk of HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(6):1007–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaber WL, Parrilo AV. Adolescents and sexually transmitted diseases. Journal of School Health. 1992;62(7):331–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1992.tb01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santelli JS, Brener ND, Lowry R, Bhatt A, Zabin LS. Multiple sexual partners among US adolescents and young adult. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30(6):271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg MD, Gurvey JE, Adler N, Dunlop M, Ellen JM. Concurrent sex partners and risk for sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26(4):208–212. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson EH, Jackson LA, Hinkle Y, Gilbert D, Hoopwood T, Lollis CM, Willis C, Grant L. What is the significance of black-white differences in risky sexual behavior? Journal of National Medical Association. 1994;86(10):745–759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orr DP, Langefeld CD. Factors associated with condom use by sexually active male adolescents at risk for sexually transmitted disease. Pediatrics. 1993;91(5):873–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Donnell L, O'Donnell CR, Stueve A. Early sexual initiation and subsequent sex-related risks among urban minority youth: the Reach for Health Study. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33(6):268–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonenstein FL, Pleck JH, Ku LC. Levels of sexual activity among adolescent males. Family Planning Perspectives. 1991;23(4):162–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. Concurrent sexual partnerships among men in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(12):2230–2237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorbach PM, Stoner BP, Aral SO, WL HW, Holmes KK. “It takes a village”: understanding concurrent sexual partnerships in Seattle, Washington. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29(8):453–462. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doherty IA, Padian NS, Marlow C, Aral SO. Determinants and consequences of sexual networks as they affect the spread of sexually transmitted infections. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S42–54. doi: 10.1086/425277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dariotis JK, Sonestein FL, Gates GJ, Capps R, Astone NM, Pleck JH, Sifakis F, Zeger S. Changes in sexual risk behaviors as young men transition to adulthood. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2008;40(4):218–225. doi: 10.1363/4021808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonenstein FL, Ku L, Lindberg LD, Turner CF, Pleck JH. Changes in sexual behavior and condom use among teenage men: 1988 to 1995. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(6):956–959. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carley ML, Lang EL. National Survey of Adolescent Males, Old Cohort, Waves 1–3, 1988, 1990–91, 1995: A user's guide to the machine-readable files and documentation (Data Set P1-P4) Sociometrics Corporation, Data Archive on Adolescent Pregnancy and Pregnancy Prevention; Los Altos, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ku L, et al. Risk Behaviors, Medical Care, and Chlamydial Infection Among Young Men in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(7):1140–1143. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.7.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Billy JO, et al. The sexual behavior of men in the United States. Family Planning Perspectives. 1993;25(2):52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laumann EO, et al. The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T. A general theory of adolescent problem behavior: problems and prospects. In: Ketterlinus RD, Lamb ME, editors. Adolescent Problem Behavior: Issues and Research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC, U.S. Census Bureau . Current Population Reports, P60-236, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2008. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crissey SR, U.S. Census Bureau . Current Population Reports, P20-560, Educational Attainment in the United States: 2007. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26(5):250–261. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aral SO, Hughes JP, Stoner B, Whittington W, Handsfield HH, Anderson RM, et al. Sexual mixing patterns in the spread of gonococcal and chlamydial infections. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(6):825–833. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Contextual factors and the black-white disparity in heterosexual HIV transmission. Epidemiology. 2002;13(6):707–712. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200211000-00016. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris M, Kurth AE, Hamilton DT, Moody J, Wakefield S. Concurrent partnerships and HIV prevalence disparities by race: linking science and public health practice. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(6):1023–1031. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coates TJ. Strategies for modifying sexual behavior for primary and secondary prevention of HIV disease. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58(1):57–69. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellen JM. The next generation of HIV prevention for adolescent females in the United States: linking behavioral and epidemiologic sciences to reduce incidence of HIV. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80(4 Suppl 3):iii40–49. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Auerswald CL, Muth SQ, Brown B, Padian N, Ellen J. Does partner selection contribute to sex differences in sexually transmitted infection rates among African American adolescents in San Francisco? Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33(8):480–484. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204549.79603.d6. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]