Abstract

Background:

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Although antibiotic therapy is usually effective early in the disease, relapse may occur when administration of antibiotics is discontinued. Studies have suggested that resistance and recurrence of Lyme disease might be due to formation of different morphological forms of B. burgdorferi, namely round bodies (cysts) and biofilm-like colonies. Better understanding of the effect of antibiotics on all morphological forms of B. burgdorferi is therefore crucial to provide effective therapy for Lyme disease.

Methods:

Three morphological forms of B. burgdorferi (spirochetes, round bodies, and biofilm-like colonies) were generated using novel culture methods. Minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration of five antimicrobial agents (doxycycline, amoxicillin, tigecycline, metronidazole, and tinidazole) against spirochetal forms of B. burgdorferi were evaluated using the standard published microdilution technique. The susceptibility of spirochetal and round body forms to the antibiotics was then tested using fluorescent microscopy (BacLight™ viability staining) and dark field microscopy (direct cell counting), and these results were compared with the microdilution technique. Qualitative and quantitative effects of the antibiotics against biofilm-like colonies were assessed using fluorescent microscopy and dark field microscopy, respectively.

Results:

Doxycycline reduced spirochetal structures ∼90% but increased the number of round body forms about twofold. Amoxicillin reduced spirochetal forms by ∼85%–90% and round body forms by ∼68%, while treatment with metronidazole led to reduction of spirochetal structures by ∼90% and round body forms by ∼80%. Tigecycline and tinidazole treatment reduced both spirochetal and round body forms by ∼80%–90%. When quantitative effects on biofilm-like colonies were evaluated, the five antibiotics reduced formation of these colonies by only 30%–55%. In terms of qualitative effects, only tinidazole reduced viable organisms by ∼90%. Following treatment with the other antibiotics, viable organisms were detected in 70%–85% of the biofilm-like colonies.

Conclusion:

Antibiotics have varying effects on the different morphological forms of B. burgdorferi. Persistence of viable organisms in round body forms and biofilm-like colonies may explain treatment failure and persistent symptoms following antibiotic therapy of Lyme disease.

Keywords: Lyme disease, spirochetes, cysts, round bodies, biofilms

Introduction

Lyme disease is a tickborne illness that was originally described in Old Lyme, Connecticut, in 1975 and subsequently shown to be caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi.1–4 The disease is transmitted by tick vectors of the genus Ixodes.2–4 The life cycle and distribution of these tick vectors involves rodents, reptiles, birds, and deer.2–4 Lyme disease sometimes begins with a skin rash called erythema migrans following a tick bite. The rash may be followed a few weeks or months later by fatigue, musculoskeletal symptoms, neurologic problems, and/or cardiac abnormalities.1–4

Over the last 10 years, Lyme disease has grown into a major public health problem in the USA and central Europe.5–7 The disease occurs in all age groups with equal prevalence in men and women.5–7 In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the number of Lyme disease cases has doubled during the last 15 years.5 In 2008, a total of 3896 cases of Lyme borreliosis were reported in Connecticut.5 However, these figures do not reflect the true incidence of Lyme disease because in 2003 Connecticut stopped requiring mandatory laboratory reporting of the disease.5 Therefore, the true number of Lyme disease cases may be at least 10-fold higher than reported.5–7 The increasing trend of the disease has been ascribed to ineffective preventive measures, suboptimal treatment regimens, and incomplete understanding of the nature of the causative spirochete.

The frontline treatment for Lyme disease is administration of antibiotics such as doxycycline, minocycline, amoxicillin, cefuroxime, and ceftriaxone.8–14 Although treatment of early Lyme disease is generally successful, studies have shown that in spite of short-course antibiotic therapy of 2–4 weeks, some patients are not successfully treated and go on to develop persistent Lyme disease symptoms.8–11 Also, in the absence of sufficient antibiotic treatment in animals and humans, relapse of the disease may occur, suggesting that even after antibiotic treatment, the host immune system fails to prevent recurrence.12–14 A possible explanation for this clinical observation is the presence of different morphological forms of B. burgdorferi with differences in sensitivity to the antibiotic treatment.15–30

In this study, we developed novel evaluation methods involving optimal culture conditions for three different forms of B. burgdorferi (spirochetes, round bodies, and biofilm-like colonies) and improved bacterial viability determination techniques. These techniques were used to test the effectiveness of antibiotics commonly used for Lyme disease treatment against the different forms of B. burgdorferi. Our goal was to establish a useful in-vitro system to mimic the in-vivo effects of antibiotics on B. burgdorferi in order to develop better therapeutic approaches for Lyme disease.

Materials and methods

Culturing B. burgdorferi

Low passage isolates of the B31 and S297 strains of B. burgdorferi were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA. B. burgdorferi was cultured in Barbour-Stoner-Kelly H (BSK-H) complete medium, with 6% rabbit serum (Sigma, St Louis, MO, #B8291). The cultures were incubated at 33°C with 5% CO2 and maintained in sterile 15 mL glass tubes without antibiotics. Homogeneous cultures having only one form (spirochete) of B. burgdorferi were obtained by maintaining the cultures in a shaking incubator at 33°C and 250 rpm. At 250 rpm, there is no biofilm formation, and the culture remains homogeneous (E Sapi, unpublished observation).

The methods for generation and detection of round body forms of B. burgdorferi using culture tubes and dark field or fluorescent microscopy are described below. For generation of biofilm-like colonies of B. burgdorferi, spirochetes were inoculated in four-well chambers (BD BioCoat™ CultureSlides, BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD, #354557) or 24-well plates (BD BioCoat™ Multiwell Plates, BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD, #354408) coated with rat-tail collagen type I and incubated for 1 week without shaking. After the 1-week incubation, biofilm-like colonies were visualized using the qualitative and quantitative methods described below.

In-vitro testing of the antibacterial agents

Standard microdilution technique

To determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the antibiotics tested (the lowest concentration that will inhibit visible growth of B. burgdorferi spirochetes after a 72-hour incubation period), a standard microdilution method was used.31–33 For this procedure, 1 × 106 spirochetes were inoculated into each well of a 48-well tissue culture microplate containing 1 mL of BSK-H medium per well. The cultures were then treated with 100 μL of each antibiotic diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Control cultures were treated with PBS alone, and all experiments were run in triplicate. The well plate was covered with parafilm and placed in the incubator for 72 hours. Cell proliferation was assessed using a bacterial counting chamber (Petroff-Hausser Counter-3902) after the 72-hour incubation.

To determine the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the antibiotics tested (the minimum concentration beyond which no spirochetes can be subcultured after a 3-week incubation period), wells of a 48-well plate were filled with 1 mL of BSK-H medium, and 20 μL of antibiotic-treated spirochetes were added into each of the wells, in triplicate. The well plate was wrapped with parafilm and placed in the incubator for 3 weeks (21 days). After the incubation period, the plate was removed and observed for motile spirochetes in the culture.

Dark field microscopy and fluorescent microscopy

To further test the effect of antibiotics on spirochete and round body forms of B. burgdorferi, the antibiotics were added to a set of 2-mL polystyrene culture tubes containing spirochetes at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL and incubated at 33°C with 5% CO2. These cultures were incubated for various time periods (24 hours, 48 hours, 72 hours, and 3 weeks) and cellular growth was scored. For each of these timepoints, cell proliferation assays were performed by directly counting the different morphological forms of B. burgdorferi using a bacterial counting chamber and dark field microscopy. Also, by performing LIVE/DEAD® BacLight™ Bacterial Viability Assay (Molecular Probes, Inc, Eugene, OR), the ratio of live (green) and dead (red) B. burgdorferi morphological forms was calculated by counting these forms using a bacterial counting chamber and fluorescent microscopy (see below). For the dark field and fluorescent microscopy experiments, a Nikon Eclipse I–series CF160 microscope was used (kindly donated by Dr Alan MacDonald and Turn the Corner Foundation).

Qualitative analysis of biofilm-like colonies

To qualitatively determine the effect of antibiotics on biofilm-like colonies of B. burgdorferi, 1 × 107 cells/mL from a homogeneous culture of spirochetes were inoculated in a collagen-coated four-well plate and incubated for 1 week. After the 1-week incubation, biofilm-like colonies were seen in the wells. These biofilm-like colonies were treated with various concentrations of antibiotics diluted in PBS. Control wells were treated with PBS alone, and cultures were run in triplicate. Plates were incubated for 72 hours, and wells were fixed with 500 μL of cold alcohol-formalin-acetic acid (AFA) for 20 minutes. The wells were then stained with 200 μL of 2 × BacLight™ staining mixture for 15 minutes in the dark. Coverslips were applied using fluorescent mounting media, and pictures were immediately taken of control and treated wells.

Quantitative analysis of biofilm-like colonies after treatment with antibiotics

To quantify B. burgdorferi biofilm-like colonies after treatment with various antibiotics, collagen-coated 24-well plates were inoculated with 2 × 106 cells/mL from a homogeneous culture of B. burgdorferi. The plates were incubated for 7 days to generate biofilm-like colonies, and then treated with various concentrations of antibiotics diluted in PBS or with PBS alone, as described above. The plates were incubated for 72 hours, and wells were stained with 1 mL of crystal violet (0.1%) for 10 minutes. After 1 mL of 95% ethanol was added to extract stain, the biofilm-like colonies were washed twice with PBS and visualized at an optical density of 570 nm using a BioTek spectrophotometer.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by two-sample paired t-test using NCSS statistical software (NCSS LLC, Kaysville, UT).

Results

To compare results from different culture techniques, MIC and MBC values for antibiotic treatments were calculated and compared with published data (Table 1). The standard published microdilution method involves culturing B. burgdorferi in microwell plates, while the new methodology made use of 2-mL polystyrene test tubes. We observed a significant difference in MIC and MBC values between the two methods. Both MIC and MBC values were in agreement with published data when evaluated by the microdilution protocol. Using the novel culture tube method, MIC values increased >63-fold for doxycycline, >333-fold for tigecycline, >333-fold for amoxicillin, >833-fold for metronidazole, and >694-fold for tinidazole, compared with our microdilution values (Table 1). Furthermore, MBC values increased >8-fold for doxycycline, >80-fold for tigecycline, >40-fold for amoxicillin, >50-fold for metronidazole, and >25-fold for tinidazole, compared with our microdilution values (Table 1). Since these MIC and MBC results suggested that our novel method used more optimal culture conditions that allowed the organisms to resist antibiotic treatment, we based further experiments on this method.

Table 1.

MIC and MBC determination by different methodsa

| Antibiotics | Microdilution method/literature data (MIC) μg/mL |

Our data (MIC) μg/mL |

Microdilution method/literature data (MBC) μg/mL |

Our data (MBC) μg/mL |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microdilution method | Direct cell counting | BacLight™ staining | Microdilution method | Direct cell counting | BacLight™ staining | |||

| Doxycycline | 0.06–2.00 | 0.4 | >25 | >25 | 0.25–6.40 | 25 | >200 | >200 |

| Tigecycline | 0.006 | 0.015 | >5 | >5 | 0.05 | 0.125 | >10 | >10 |

| Amoxicillin | 0.03–2.00 | 0.3 | >100 | >100 | <0.03–32.00 | 5 | >200 | >200 |

| Metronidazole | 0.06–32.00 | 0.3 | >250 | >250 | >4 | 10 | >500 | >500 |

| Tinidazole | – | 0.09 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >128 | 10 | >250 | >250 |

Notes:

Comparison of MIC and MBC values for different antibiotics by standard microdilution method (published literature and our data) and novel direct cell counting and fluorescent BacLight™ staining methods in reference to spirochete forms of Borrelia burgdorferi B31.

Abbreviations: MBC, minimum bactericidal concentration; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

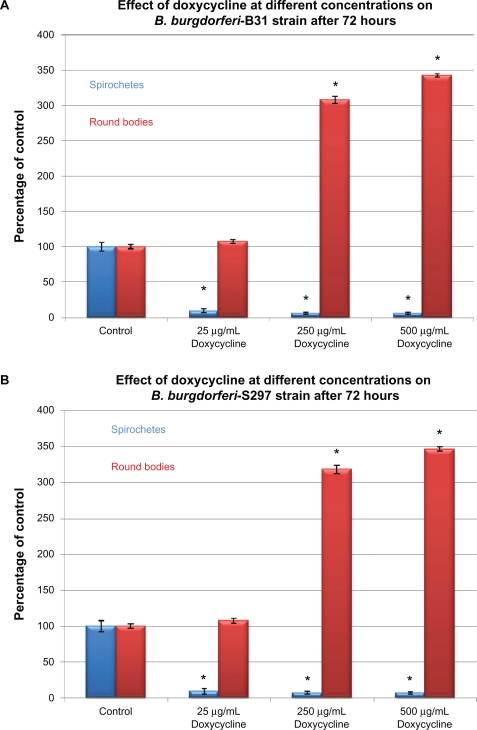

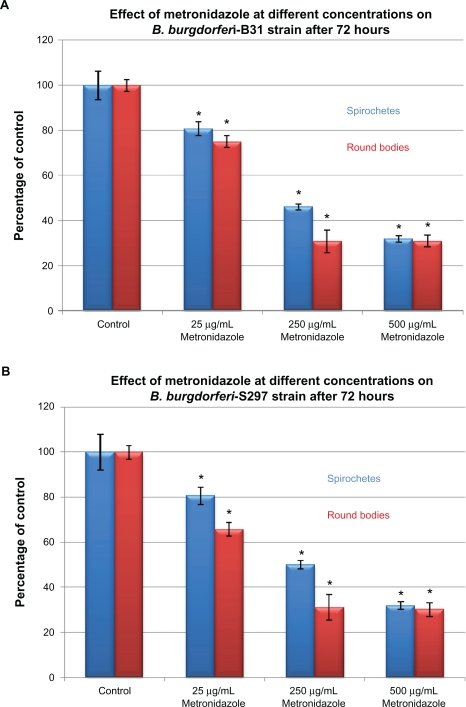

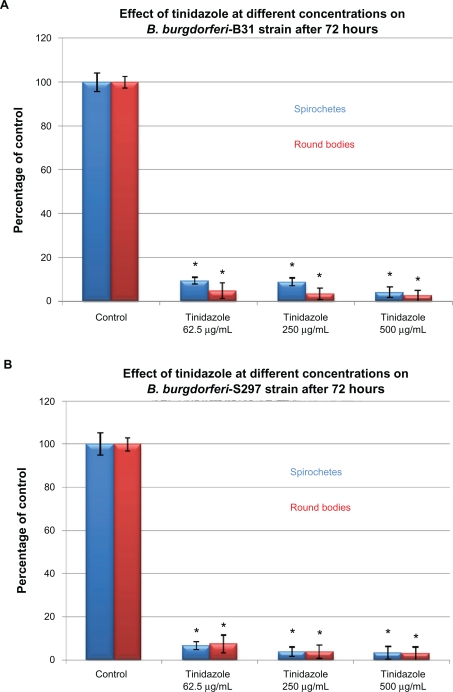

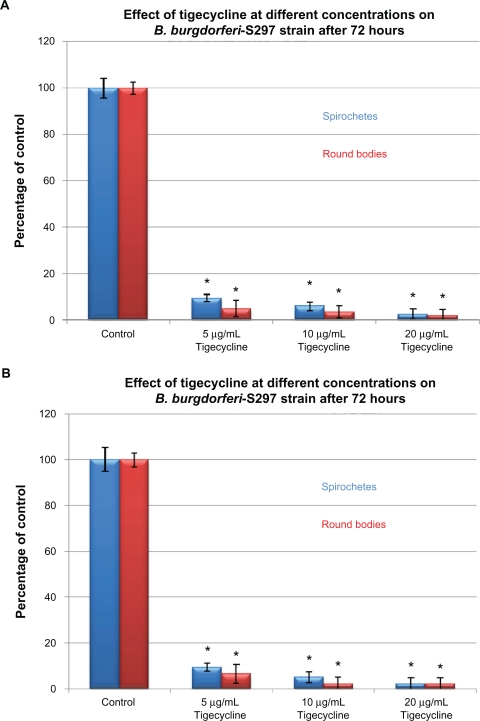

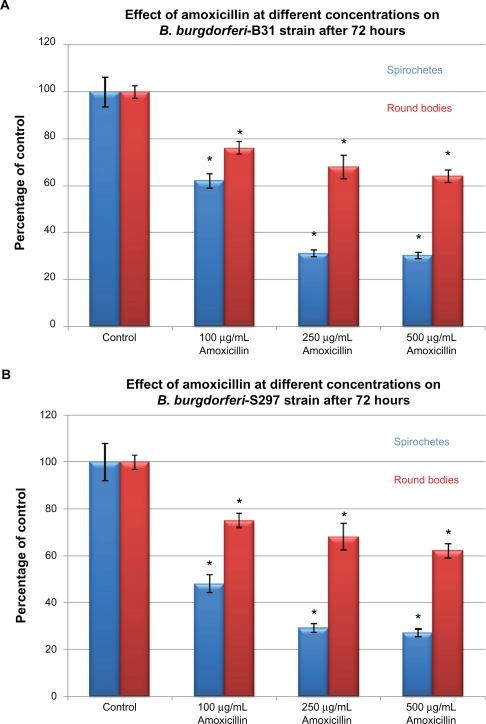

To evaluate in-vitro antibiotic sensitivity of spirochete and round body morphological forms, two strains of B. burgdorferi (B31 and S297) were incubated for 72 hours with different antibiotics at concentrations above the calculated MIC and MBC. Antibiotic sensitivity was evaluated using the direct cell counting and dark field morphological evaluation methods (Figure 1). Treatment with these higher concentrations showed that doxycycline reduced spirochetal structures ∼90% but increased the number of cystic round body forms about twofold (Figure 1A). Treatment with metronidazole led to reduction of both spirochetal and cystic round body forms by ∼70% (Figure 1B). Treatment with either tigecycline or tinidazole reduced both spirochetal and cystic round body forms by ∼80%–90% (Figures 1C and 1D). Amoxicillin reduced spirochetal structures ∼70% and cystic round body forms by ∼68% (Figure 1E). No difference was seen in antibiotic sensitivity testing between the two strains of B. burgdorferi (B31 and S297). Using this method, we found that the most effective doses of the antibiotics against the spirochete forms of B. burgdorferi were 250 μg/mL for doxycy-cline, 250 μg/mL for metronidazole, 20 μg/mL for tigecycline, 500 μg/mL for tinidazole, and 250 μg/mL for amoxicillin.

Figure 1A.

Susceptibility of the spirochete and round body forms of strain B31 (top panels) and strain S297 (bottom panels) of B. burgdorferi to different concentrations (between calculated MIC and MBC) of five antibiotics after 72-hour treatment measured by dark-field microscopy.

Note: *P values <0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with control.

Figure 1B.

Susceptibility of the spirochete and round body forms of strain B31 (top panels) and strain S297 (bottom panels) of B. burgdorferi to different concentrations (between calculated MIC and MBC) of five antibiotics after 72-hour treatment measured by dark-field microscopy.

Note: *P values <0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with control.

Figure 1C.

Susceptibility of the spirochete and round body forms of strain B31 (top panels) and strain S297 (bottom panels) of B. burgdorferi to different concentrations (between calculated MIC and MBC) of five antibiotics after 72-hour treatment measured by dark-field microscopy.

Note: *P values <0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with control.

Figure 1D.

Susceptibility of the spirochete and round body forms of strain B31 (top panels) and strain S297 (bottom panels) of B. burgdorferi to different concentrations (between calculated MIC and MBC) of five antibiotics after 72-hour treatment measured by dark-field microscopy.

Note: *P values <0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with control.

Figure 1E.

Susceptibility of the spirochete and round body forms of strain B31 (top panels) and strain S297 (bottom panels) of B. burgdorferi to different concentrations (between calculated MIC and MBC) of five antibiotics after 72-hour treatment measured by dark-field microscopy.

Note: *P values <0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with control.

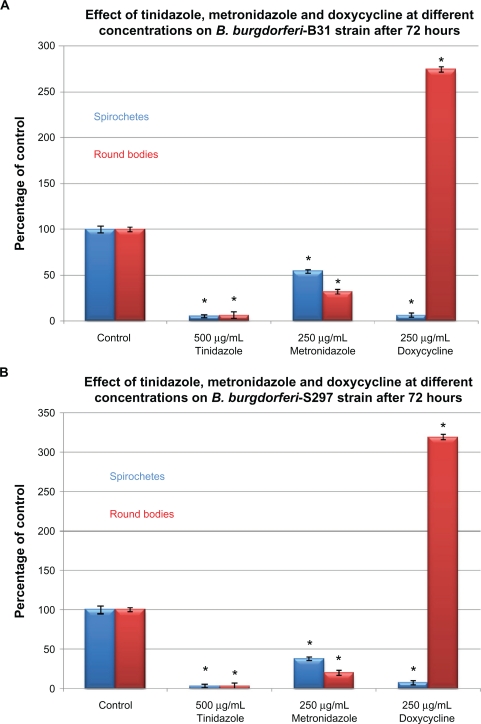

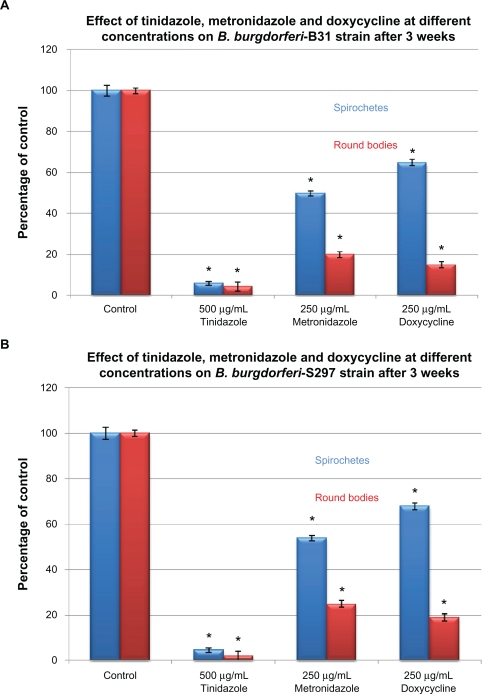

To examine in-vitro persistence of spirochete and round body forms of B. burgdorferi, the B31 and S297 strains were incubated for 72 hours and then evaluated by the direct cell counting and dark field evaluation methods (Figure 2). As in the previous set of experiments, doxycycline was found to be more effective against spirochetes while metronidazole and tinidazole were more effective against round body forms (Figure 2A). To test the concept that by discontinuing antibiotics, spirochete forms persist and cystic round body forms convert back to spirochete forms, the treated cultures were sub-cultured in fresh medium without antibiotics. After 3 weeks of subculturing, doxycycline had reduced spirochetal forms by ∼45% and round bodies by ∼85%, suggesting that round body forms converted back to spirochete forms in more favorable growth conditions (fresh growth medium and no antibiotic stress). Similarly, metronidazole reduced spirochetal forms by ∼50% and round bodies by ∼80%, while tinidazole reduced spirochetal forms by ∼94% and round bodies by ∼96% (Figure 2B).

Figure 2A.

Susceptibility of the spirochete and round body forms of strain B31 (top panels) and strain S297 (bottom panels) of B. burgdorferi to the most effective concentrations of three antibiotics measured by dark-field microscopy. Tinidazole, metronidazole, and doxycycline effect on B. burgdorferi after 72-hour treatment.

Note: *P values <0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with control.

Figure 2B.

Susceptibility of the spirochete and round body forms of strain B31 (top panels) and strain S297 (bottom panels) of B. burgdorferi to the most effective concentrations of three antibiotics measured by dark-field microscopy. Tinidazole, metronidazole, and doxycycline effect on B. burgdorferi after 3 weeks of subculturing following 72-hour treatment.

Note: *P values <0.05 indicates statistical significance compared with control.

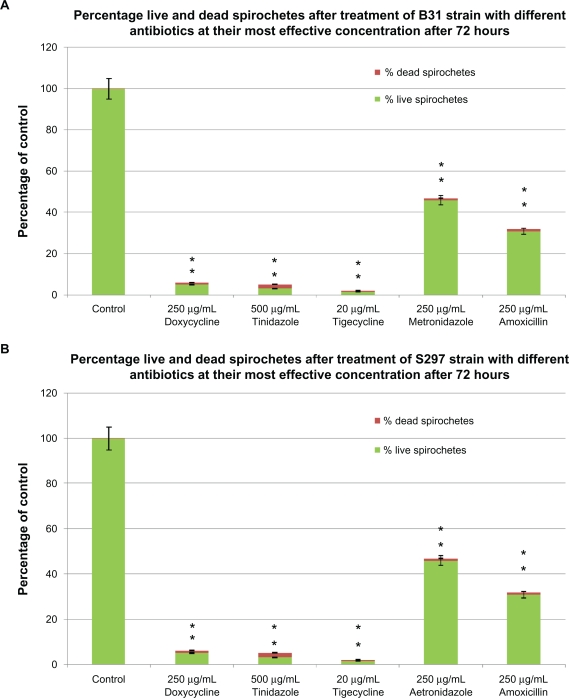

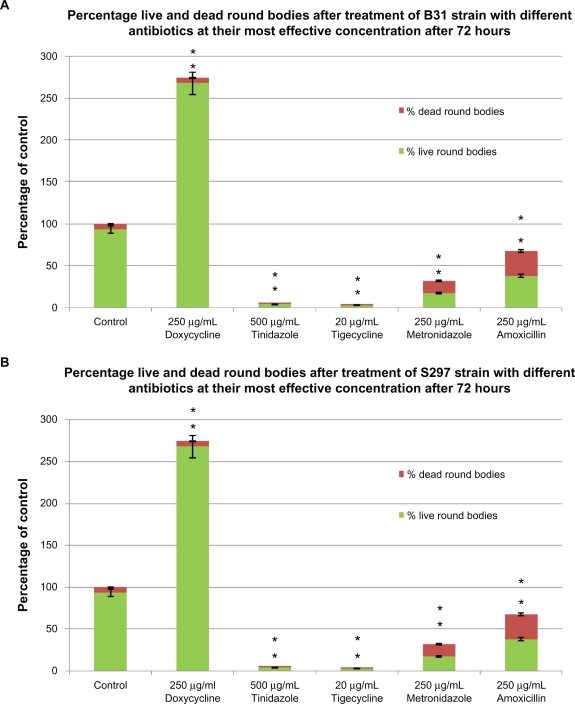

To confirm preliminary results, the B31 and S297 strains of B. burgdorferi were further evaluated in vitro for antibiotic sensitivity of spirochete and round body morphological forms by a fluorescent microscopy technique (BacLight™ staining). B. burgdorferi was incubated for 72 hours with antibiotics at concentrations higher than their calculated MIC and MBC. In this set of experiments, we calculated the post-treatment ratio of live/dead spirochetes and round bodies using SYTO®9 green-fluorescent nucleic acid stain (live cells) and propidium iodide red-fluorescent nucleic acid stain (dead cells) (Figure 3A). Doxycycline treatment reduced spirochetes by ∼94% but in the remaining 6% of the population, ∼5% were still alive (stained green) while ∼1% were dead (stained red). Tinidazole treatment reduced spirochetes by ∼95%, but in the remaining 5% of the population ∼3% were still alive while ∼2% were dead. Tigecycline treatment was most effective as this reduced spirochetes by ∼98%, and in the remaining 2% of the population ∼1.5% were still alive and ∼0.5% were dead. Metronidazole treatment reduced spirochetes by ∼54%, but in the remaining 46% of the population ∼45% were still alive and only ∼1% were dead. Amoxicillin treatment reduced spirochetes by ∼69%, but in the remaining 31% of the population ∼30% were alive and only ∼1% cells were dead (Figure 3A).

Figure 3A.

Evaluation of live/dead spirochete and round body forms of B. burgdorferi following treatment with five antibiotics measured by fluorescent microscopy using SYTO®9 green-fluorescent stain (live organisms) and propidium iodide red-fluorescent stain (dead organisms). Effect of doxycycline, tinidazole, tigecycline, metronidazole, and amoxicillin on spirochete forms of strain B31 (top panel) and strain S297 (bottom panel).

Notes: *P values calculated were <0.05 indicating statistical significance compared with control for live and dead spirochetes.

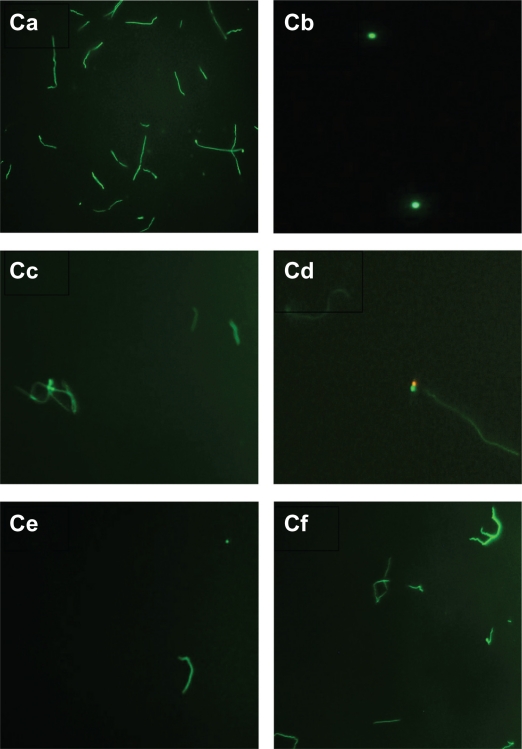

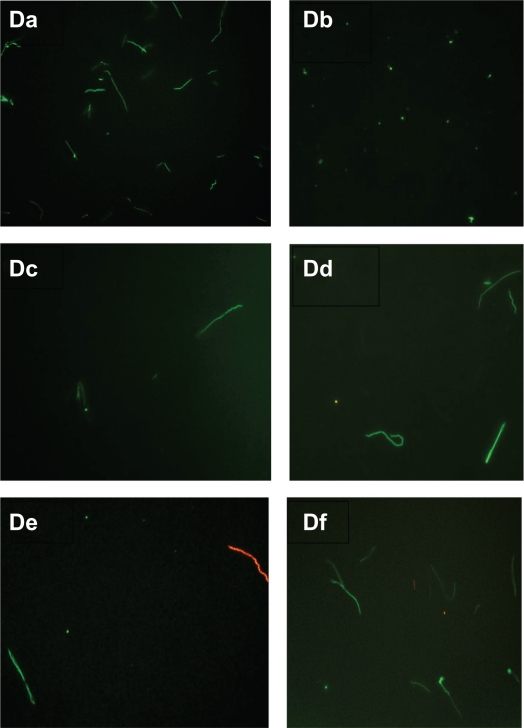

Doxycycline treatment increased round bodies by ∼275% (Figure 3B). Out of this population ∼270% were alive and only ∼5% were dead. Tinidazole treatment reduced round bodies by ∼94%, but in the remaining 6% of the population only ∼2% were dead. Tigecycline treatment reduced round bodies by ∼96%, but in the remaining 4% of population only ∼1% were dead. Metronidazole treatment reduced round bodies by ∼68%, but in the remaining 32% of the population ∼15% were dead. Amoxicillin treatment reduced round bodies by ∼32%, but in the remaining 68% of the population ∼30% were dead (Figure 3B). The microscopic appearance of the B31 and S297 strains of B. burgdorferi following treatment with each antibiotic is shown in Figures 3C and 3D, respectively.

Figure 3B.

Evaluation of live/dead spirochete and round body forms of B. burgdorferi following treatment with five antibiotics measured by fluorescent microscopy using SYTO®9 green-fluorescent stain (live organisms) and propidium iodide red-fluorescent stain (dead organisms). Effect of doxycycline, tinidazole, tigecycline, metronidazole and amoxicillin on round body forms of strain B31 (top panel) and strain S297 (bottom panel).

Notes: *P values calculated were <0.05 indicating statistical significance compared with control for live and dead round bodies.

Figure 3C.

Evaluation of live/dead spirochete and round body forms of B. burgdorferi following treatment with five antibiotics measured by fluorescent microscopy using SYTO®9 green-fluorescent stain (live organisms) and propidium iodide red-fluorescent stain (dead organisms). Visualization of spirochete and round body forms of strain B31 following antibiotic treatment measured by dark field microscopy: (Ca) Control; (Cb) Doxycycline; (Cc) Tinidazole; (Cd) Metronidazole; (Ce) Tigecycline; (Cf) Amoxicillin.

Note: All images taken at 40× magnification.

Figure 3D.

Evaluation of live/dead spirochete and round body forms of B. burgdorferi following treatment with five antibiotics measured by fluorescent microscopy using SYTO®9 green-fluorescent stain (live organisms) and propidium iodide red-fluorescent stain (dead organisms). Visualization of spirochete and round body forms of strain S297 following antibiotic treatment measured by dark field microscopy: (Da) Control; (Db) Doxycycline; (Dc) Tinidazole; (Dd) Metronidazole; (De) Tigecycline; (Df) Amoxicillin.

Note: All images taken at 40× magnification.

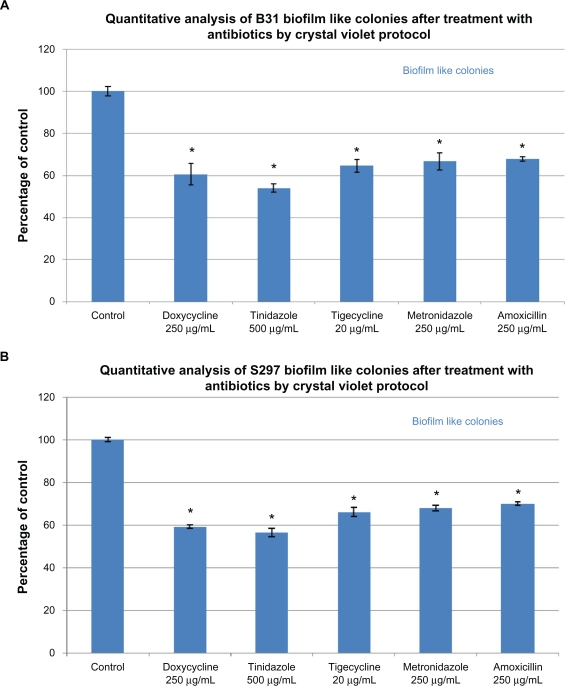

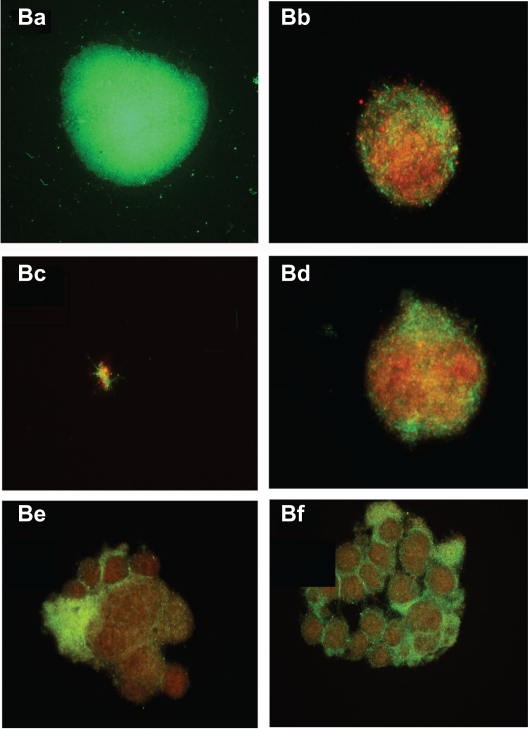

In the next experiments, a biofilm-like form of B. burgdorferi was evaluated quantitatively using a crystal violet staining method and qualitatively using the fluorescent microscopy technique (BacLight™ staining) (Figure 4). Using the quantitative staining method, doxycycline reduced biofilm-like colonies by ∼40%, tinidazole reduced biofilm-like colonies by ∼50%–55%, tigecycline reduced biofilm-like colonies by ∼35%, and amoxicillin and metronidazole reduced biofilm-like colonies by ∼30% (Figure 4A). For qualitative analysis of bacterial cells in biofilm-like colonies, cultures were treated as described above for 72 hours and stained with BacLight™ fluorescent viability stain (Figure 4B). In the absence of antimicrobial agents, B. burgdorferi form biofilm-like colonies in which ∼98% of the colonies stain green (live cells) and ∼2% red (dead cells) (Figure 4Ba). Doxycycline-treated colonies were similar in size to control colonies and ∼70% stained green and ∼30% stained red (Figure 4Bb). Tinidazole-treated colonies were very tiny and loose in their morphology, and ∼10% stained green and ∼90% stained red (Figure 4Bc). Tigecycline-treated colonies were similar in size to control colonies, and ∼70% stained green and ∼30% stained red (Figure 4Bd). Metronidazole-treated and amoxicillin-treated colonies were larger in size than control colonies, and ∼80%–85% stained green while ∼20% stained red (Figure 4Be and 4Bf).

Figure 4A.

Evaluation of biofilm-like colonies of B. burgdorferi. Quantitative analysis of biofilm-like colonies of strain B31 (top panel) and strain S297 (bottom panel) measured by crystal violet staining technique.

Figure 4B.

Evaluation of biofilm-like colonies of B. burgdorferi. Qualitative analysis of biofilm-like colonies of strain B31 measured by fluorescent microscopy using SYTO®9 green-fluorescent stain (live organisms) and propidium iodide red-fluorescent stain (dead organisms): (Ba) Control; (Bb) Doxycycline; (Bc) Tinidazole; (Bd) Tigecycline; (Be) Metronidazole; (Bf) Amoxicillin.

Note: All images taken at 40× magnification.

Discussion

The goal of our study was to demonstrate the in-vitro susceptibility of different morphological forms of B. burgdorferi to various antibiotics using improved technical approaches in order to understand why antibiotic treatment for patients with Lyme disease could fail. To successfully eradicate B. burgdorferi, antimicrobial agents should eliminate all morphological forms of the organism. Furthermore, for better demonstration of antibiotic susceptibility of different morphological forms of B. burgdorferi, there is a need for reliable in-vitro testing methods.

The spirochete form of B. burgdorferi is the most active form, with periplasmic flagella that make the organisms motile.15,16 Spirochetes can also enter into tissues and cause intracellular infection.17,18 Adverse environmental conditions such as change in temperature, pH, starvation, and most importantly antibiotic exposure can cause a phenotypic change in the spirochete.19,20 This change involving surface proteins is hypothesized to be the way in which the spirochete evades the host immune system.

The change in phenotypic expression could also lead to structural alterations in the spirochete form and induction of the cyst form, a knob-shaped structure containing one or multiple spirochetes.21–24 Cysts have a low metabolic rate that enables them to survive in a hostile environment until conditions become favorable for them to multiply again.21–25 These cyst forms have been detected in spinal fluid, and have been linked to neuroborreliosis.22 The spirochetes can also disintegrate into minute particles called granules.25 These granules are liberated through the periplasmic sheath surrounding the spirochete body by budding and extrusion, and they may also be transmissible.25 Both cysts and granules are together referred to as round body forms in this study. Several studies have shown that B. burgdorferi can convert from the spirochete form to the round body form in vitro when presented with an unfavorable environment, and the organism can revert back to the spirochete form when conditions are again favorable for growth.21–24 The presence of atypical forms of B. burgdorferi may be the reason why the spirochete can survive in infected tissues for years or even for decades.21–24

In addition to round body forms, we and others recently noted that B. burgdorferi has the capability to form organized structures called biofilm-like colonies.26,27 Biofilms are adherent polysaccharide-based matrices that protect bacteria from the hostile host environment and facilitate persistent infection.28–30 These organized structures are responsible for a number of chronic infections, including periodontitis, chronic otitis media, endocarditis, gastrointestinal infection, and chronic lung infection. Formation of biofilm-like colonies would allow B. burgdorferi to survive various environmental stresses including exposure to antibacterial agents.28–30 Recent studies suggest that bacteria live in an environment deep within the biofilm-like colonies where diffusion of antibiotics might be difficult, and in that state the bacteria could become 1000 times more resistant to antibiotics.28–30 This resistance could also be one of the reasons why conventional antibiotic therapy that is usually effective against free-floating bacteria becomes ineffective once a pathogen forms biofilm-like colonies.28–30

In this study, novel methods of in-vitro antibiotic susceptibility evaluation were used. These methods include optimal culture and treatment conditions such as the culture apparatus (tubes, to limit oxygen content), temperature, density of inoculum, amount of culture medium, and CO2 level.34,35 These methods should counteract problems with culture variability of B. burgdorferi strains that have been described in the past.36,37 Furthermore our novel procedures involve better bacterial viability determination methods such as fluorescent and dark field microscopy. These microscopic evaluation methods are more reliable and sensitive than the standard published bacterial viability determination protocols.38,39 Being metabolically inactive, round body forms of B. burgdorferi could not be detected by standard protocols, but they can be directly visualized under the microscope by our novel evaluation methods. This explains why the standard protocols measure effectiveness of antibiotics only in reference to metabolically active spirochete forms while our novel antibiotic sensitivity study measures effectiveness of antibiotics in reference to all morphological forms of B. burgdorferi.

We found that doxycycline significantly reduced the spirochete form of B. burgdorferi (∼90%) but also increased the round body forms twofold. Amoxicillin reduced spirochetal forms by ∼85%–90% and round body forms by ∼68%. In contrast, metronidazole, tinida-zole, and tigecycline significantly decreased both the spirochete and the round body forms of B. burgdorferi, but live organisms could still be detected following treatment with these agents. Furthermore, the antibiotics studied were equally effective or ineffective against two different strains (B31 and S297) of B. burgdorferi. This observation confirms the reliability of our experimental technique. It remains to be seen whether combinations of antibiotics would be more effective than individual antibiotics alone in our in-vitro culture system.

Our results delineate antibiotic concentrations that are effective in vitro. Whether equivalent concentrations can be attained with clinical use of these agents in vivo remains to be determined.39–45 An in-vitro study showed that tige-cycline destroyed the spirochete and round body forms of B. burgdorferi.39 However, an in-vivo study in mice showed that tigecycline was ineffective during the late stage of Lyme disease based on the persistence of viable and infectious but nondividing or slowly dividing organisms in the animals.46 Our study demonstrated that tigecycline was effective against the spirochete and round body forms of B. burgdorferi but was not effective against the biofilm-like mass. One possible explanation for the conflicting in-vitro and in-vivo results could be the presence of these biofilm-like colonies in the late stage of the disease, which renders B. burgdorferi more resistant against the antibiotic. Another possibility is that intracellular invasion of the spirochete in vivo could protect it from the action of antibiotics.17,18 Further evaluation of B. burgdorferi localization in tissues and biofilm-like masses is warranted.

To summarize, this study outlines novel in-vitro methods to determine optimal growth conditions for B. burgdorferi. The study also describes novel microscopic viability determination methods to assess three morphological forms of B. burgdorferi (spirochetes, round bodies, and biofilm-like colonies), and the methods were used to evaluate antibiotic susceptibility of the different morphological forms of this complex organism. Our in-vitro methodology will facilitate the design of experiments that mimic tissue-based in-vivo conditions in order to optimize the antibiotic treatment of Lyme disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Willy Burgdorfer, Robert Lane, Alan MacDonald, Christian Melander, and Yi Zhang for helpful discussion. We are also grateful to Lorraine Johnson, Kris Newby, and Pam Weintraub for their input. This work was supported by grants from the California Lyme Disease Association, Turn the Corner Foundation and the University of New Haven. Ethical approval was not required for this research study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

RBS serves without compensation on the medical advisory panel for QMedRx Inc. He has no financial ties to the company. The other coauthors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Burgdorfer W, Barbour AG, Hayes SF, Benach JL, Grunwaldt E, Davis JP. Lyme disease-a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science. 1982;216:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.7043737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stricker RB, Johnson L. Lyme disease: the next decade. Infect Drug Resist. 2011;4:1–9. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S15653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Dam AP, Kuiper H, Vos K, et al. Different genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi are associated with distinct clinical manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:708–717. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stricker RB, Johnson L. Lyme disease diagnosis and treatment: lessons from the AIDS epidemic. Minerva Med. 2010;101:419–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacon RM, Kugeler KJ, Mead PS, for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Surveillance for Lyme disease – United States, 1992–2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meek JI, Roberts CL, Smith EV, Cartter ML. Underreporting of Lyme disease by Connecticut physicians, 1992. J Public Health Manag Pract. 1996;2:61–65. doi: 10.1097/00124784-199623000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boltri JM, Hash RB, Vogel RL. Patterns of Lyme disease diagnosis and treatment by family physicians in a southeastern state. J Community Health. 2002;27:395–402. doi: 10.1023/a:1020697017543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liegner KB, Shapiro JR, Ramsay D, Halperin AJ, Hogrefe W, Kong L. Recurrent erythema migrans despite extended antibiotic treatment with minocycline in a patient with persisting Borrelia burgdorferi infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2 Pt 2):312–314. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70043-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donta ST. Tetracycline therapy for chronic Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(Suppl 1):S52–S56. doi: 10.1086/516171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donta ST. Macrolide therapy of chronic Lyme disease. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:136–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krause PJ, Foley DT, Burke GS, Christianson D, Closter L, Spielman A. Reinfection and relapse in early Lyme disease. Am Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:1090–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodzic E, Feng S, Holden K, Freet K, Barthold SW. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi following antibiotic treatment in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1728–1736. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01050-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straubinger RK. PCR-based quantification of Borrelia burgdorferi organisms in canine tissues over a 500-day post-infection period. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2191–2199. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2191-2199.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oksi J, Marjamaki M, Nikoskelainen J, Viljanen MK. Borrelia burg-dorferi detected by culture and PCR in clinical relapse of disseminated Lyme borreliosis. Ann Med. 1999;31:225–232. doi: 10.3109/07853899909115982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge Y, Li C, Corum L, Slaughter CA, Charon NW. Structure and expression of the FlaA periplasmic flagellar protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2418–2425. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2418-2425.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sal MS, Li C, Motalab MA, Shibata S, Aizawa S, Charon NW. Borrelia burgdorferi uniquely regulates its motility genes and has an intricate fla-gellar hook-basal body structure. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1912–1921. doi: 10.1128/JB.01421-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livengood JA, Gilmore RJ. Invasion of human neuronal and glial cells by an infectious strain of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:2832–2840. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J, Weening EH, Faske JB, Höök M, Skare JT. Invasion of eukaryotic cells by Borrelia burgdorferi requires β1 integrins and Src kinase activity. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1338–1348. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01188-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alban PS, Johnson PW, Nelson DR. Serum-starvation-induced changes in protein synthesis and morphology of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology. 2000;146:119–127. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-1-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramamoorthy R, Scholl-Meeker D. Borrelia burgdorferi proteins whose expression is similarly affected by culture temperature and pH. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2739–2742. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2739-2742.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murgia R, Cinco M. Induction of cystic forms by different stress conditions in Borrelia burgdorferi. APMIS. 2004;112:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm1120110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brorson Ø, Brorson SH. In vitro conversion of Borrelia burgdorferi to cystic forms in spinal fluid, and transformation to mobile spirochetes by incubation in BSK-H medium. Infection. 1998;26:144–150. doi: 10.1007/BF02771839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brorson Ø, Brorson SH. Transformation of cystic forms of Borrelia burg-dorferi to normal mobile spirochetes. Infection. 1997;25:240–246. doi: 10.1007/BF01713153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Robaiy S, Dihazi H, Kacza J, et al. Metamorphosis of Borrelia burgdorferi organisms – RNA, lipid and protein composition in context with the spirochetes’ shape. J Basic Microbiol. 2010;50(Suppl 1):S5–S17. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kersten A, Poitschek C, Rauch S, Aberer E. Effects of penicillin, ceftriaxone, and doxycycline on morphology of Borrelia burgdorferi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1127–1133. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.5.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sapi E, MacDonald A. Biofilms of Borrelia burgdorferi in chronic cutaneous borreliosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:988–989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisendle K, Müller H, Zelger B. Biofilms of Borrelia burgdorferi in chronic cutaneous borreliosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:989–990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeffereson KK. What drives bacteria to form a biofilm? FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;52:917–924. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart P, Costerton JW. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms. Lancet. 2001;358:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenburg EP. Bacterial biofilms, a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunfeld KP, Kraiczy P, Kekoukh E, Schäfer V, Brade V. Standardized in vitro susceptibility testing of Borrelia burgdorferi against well-known and newly developed antimicrobial agents – possible implications for new therapeutic approaches to Lyme disease. Int J Med Microbiol. 2002;291(Suppl 33):125–137. doi: 10.1016/s1438-4221(02)80024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dever LL, Jorgensen JH, Barbour AG. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Borrelia burgdorferi: a micro-dilution MIC method and time-kill studies. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2692–2697. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2692-2697.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boerner J, Failing K, Wittenbrink MM. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Borrelia burgdorferi: influence of test conditions on minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1995;283:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80890-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegemund M, van Bommel J, Ince C. Assessment of regional tissue oxygenation. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1044–1060. doi: 10.1007/s001340051011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkatesh B, Morgan TJ, Lipman J. Subcutaneous oxygen tensions provide similar information to ileal luminal CO2 tensions in an animal model of hemorrhagic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:592–600. doi: 10.1007/s001340051209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruzic-Sabljic E, Strle F. Comparison of growth of Borrelia afzelii, B. garinii, and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in MKP and BSK-II medium. Int J Med Microbiol. 2004;294:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang G, Iyer R, Bittker S, et al. Variations in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly culture medium modulate infectivity and pathogenicity of Borrelia burgdorferi clinical isolates. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6702–6706. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6702-6706.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brorson Ø, Brorson SH. An in vitro study of the susceptibility of mobile and cystic forms of Borrelia burgdorferi to tinidazole. International Microbiol. 2004;7:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brorson Ø, Brorson SH, Scythes J, MacAllister J, Wier A, Margulis L. Destruction of spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi round-body propagules (RBs) by the antibiotic tigecycline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18656–18661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908236106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazzei T, Mini E, Novelli A, Periti P. Chemistry and mode of action of macrolides. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31(Suppl C):1–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_c.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chopra I, Roberts M. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:232–260. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tenson T, Lovmar M, Ehrenberg M. The mechanism of action of macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramin B reveals the nascent peptide exit path in the ribosome. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:1005–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kasbekar N, Acharya PS. Telithromycin: the first ketolide for the treatment of respiratory infections. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:905–916. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.9.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldman P. The development of 5-nitroimidazoles for the treatment and prophylaxis of anaerobic bacterial infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1982;10:23–33. doi: 10.1093/jac/10.suppl_a.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slover CM, Rodvold KA, Danziger LH. Tigecycline: a novel broad-spectrum antimicrobial. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:965–972. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barthold SW, Hodzic E, Imai DM, Feng S, Yang X, Luft BJ. Ineffectiveness of tigecycline against persistent Borrelia burgdorferi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:643–651. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00788-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]