Abstract

Background:

Cutaneous manifestations of deep mycotic infection are fraught with delayed or misdiagnosis from mainly cutaneous neoplastic lesions.

Aim:

This study is designed to present our experience of these mycoses in a pathology laboratory in the tropics.

Materials and Methods:

A clinicopathologic analysis of deep mycotic infections was conducted over a 15 years period Formalin fixed and paraffin wax processed biopsies were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid Schiff (PAS), and Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS) for the identification of fungus specie. Patients’ bio-data and clinical information were obtained from records.

Results:

Twenty males and seven females presented with 6 months to 6 years histories of varying symptoms of slow growing facial swellings, nodules, subcutaneous frontal skull swelling, proptosis, nasal blockage, epistaxis, discharging leg sinuses, flank mass, convulsion and pain. Of the 27 patients, four gave antecedent history of trauma, two had recurrent lesions which necessitated maxilectomy, two presented with convulsion without motor dysfunction while one had associated erosion of the small bones of the foot. None of the patients had debilitating illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, and HIV infection. Tissue histology revealed histoplasmosis (10), mycetoma (9), subcutaneous phycomycosis (6), and phaeohyphomycosis (2).

Conclusion:

Deep mycoses may present primarily as cutaneous lesions in immunocompetent persons and often elicit distinct histologic inflammatory response characterized by granuloma formation. Diagnosis in resource constraint setting can be achieved with tissue stained with PAS and GMS which identifies implicated fungus. Clinical recognition and adequate knowledge of the pathology of these mycoses may reduce attendant patient morbidity.

Keywords: Histoplasmosis, mycetoma, mycotic cutaneous tumors, phycomycosis

Introduction

Mycotic infections are prevalent in the tropics, though, few are exclusively tropical.[1] The geographic endemicity of deep mycoses, in particular, has been greatly distorted by globalization and prevalent immune suppression from a variety of causes, especially AIDS.[2–4] Infection can be acquired by implantation, direct inoculation, or inhalation of spores from contaminated soil and often present as respiratory diseases.[1,2,5,6] Primary cutaneous presentations in affected persons may be misdiagnosed as cutaneous tumors due to the long duration and nonspecificity of presenting symptoms. Also, the manifestation of these mycoses is dependant on host factors.[6] We present our experience of deep mycoses with primary cutaneous manifestations as seen in a pathology laboratory and a review of pertinent literature.

Materials and Methods

This is a consecutive clinicopathologic analysis of all diagnosed deep and subcutaneous mycoses over a 15-year period (1995–2009) in the Pathology department of Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital Shika-Zaria. The patients were seen in the surgical, ophthalmic, and maxillofacial clinics of the hospital. Tissue biopsies taken from representative lesions sent to the laboratory were fixed in 10% formalin, processed in paraffin wax and histology slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E), periodic acid Schiff (PAS), and Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS) stains for identification of fungial species. The bio-data of patients and relevant clinical information were obtained from accompanying case files.

Results

Twenty males and seven females aged 2–70 years were seen during the period. They presented with varying symptoms of slow-growing swellings, nodules, masses, proptosis, discharging sinuses, convulsion, and pain involving the face, jaw, palate, trunk, and limbs and the duration of symptoms ranged from 6 months to 6 years.

Ten patients had lesions in varying parts of the lower limb, four gave antecedent histories of trauma, two had recurrent lesions, and another one had associated erosion of the small bones of the foot. Facial swellings involving the maxilla with intraoral extension, nasal blockage, and epistaxis were seen in five patients while three had proptosis with visual impairment. Two other patients presented with convulsion, hemiparesis, speech disorder, and visual loss with no motor dysfunction The youngest patient, a 2-year-old child presented with an itchy right-sided firm subcutaneous swelling of leg and inguinal lymphadenopathy following intramuscular injection of DPT immunization at 6 months of age. Others had flank mass and discharging sinuses [Table 1]. One of the recurrent cases represented a year later with a second recurrence which necessitated a maxillectomy. None of the patients had any current or past history of debilitating illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, and HIV infection. However, a 53-year-old woman who had maxillectomy was a controlled hypertensive. Clinical diagnoses were made based on physical examination included fibrolipoma, fibroma, dentigerous cyst, granulomatous inflammation, ameloblastoma, lipoblastoma, orbital sarcoma, astrocytoma, and basal cell carcinoma [Table 1].

Table 1.

Clinical details and histologic diagnoses of patients with mycoses

Tissue histology of processed biopsies from the various lesions showed numerous granulomata composed of epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells containing both septate and aseptate fungial hyphae, spores and focal microabscesses surrounding aggregates of eosinophilic granules in a fibrocollagenized stroma. The fungi species were identified by PAS and GMS stains. They were diagnosed as histoplasmosis (10), mycetoma (9), subcutaneous phycomycosis (6), and phaeohyphomycosis (2).

Discussion

Cutaneous manifestation of deep mycosis is uncommon and fairly limited to a few fungi species. However, a number of dimorphic pathogenic fungi are implicated in causation of deep mycoses in immunocompromised persons.[6] These fungi may exist as moulds/hyphae or yeasts and are morphologically distinct for various species while the clinical course of disease is usually indolent and often painless. Localized cutaneous presentation is variable and may take the form of circumscribed nodules, ulcers, abscesses or papules, thus a common cause of delayed or misdiagnosis with other cutaneous neoplastic lesions.[7]

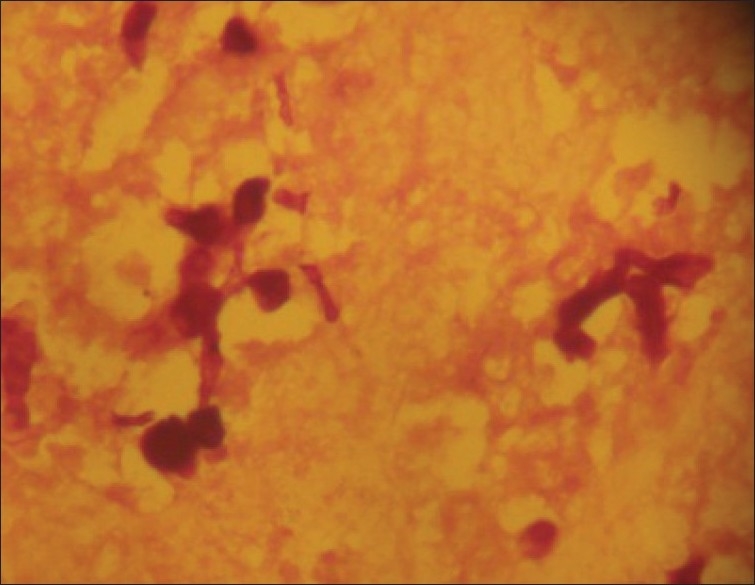

Histoplasmosis accounted for 37% of the cases with a higher frequency in males. The distribution pattern of histoplasmosis is global though with high endemicity in central eastern United States and central and sub- Saharan Africa and commonly present as a pulmonary disease with rare primary cutaneous manifestation in disseminated disease.[6,8,9] However, the African histoplasmosis caused by Histoplasma capsulatum var duboisi may affect the skin, bones and lymph nodes in immunocompetent hosts and present as localized lesions.[6,8–10] One of our 10 cases had bone affectation which necessitated a maxillectomy while the remaining nine cases affected the skin of the face, trunk, limbs, and palate, similar to documented report of 40% cases at these sites including oral mucosal surfaces.[11–14] Disseminated histoplasmosis occurs in the background of immune suppression from AIDS commonly and may be associated with central nervous system involvement in approximately 10–20% of cases.[15] The only patient with CNS involvement in this series was seronegative for HIV infection and had no history of immunosuppression. Similar reports of cerebral histoplasmosis in the absence of HIV infection have been documented in patients living in endemic areas.[16] Tissue diagnosis of histoplasmosis is based on the identification of fairly uniform round to oval spores and hyphae within multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, and extracellularly within the stroma.

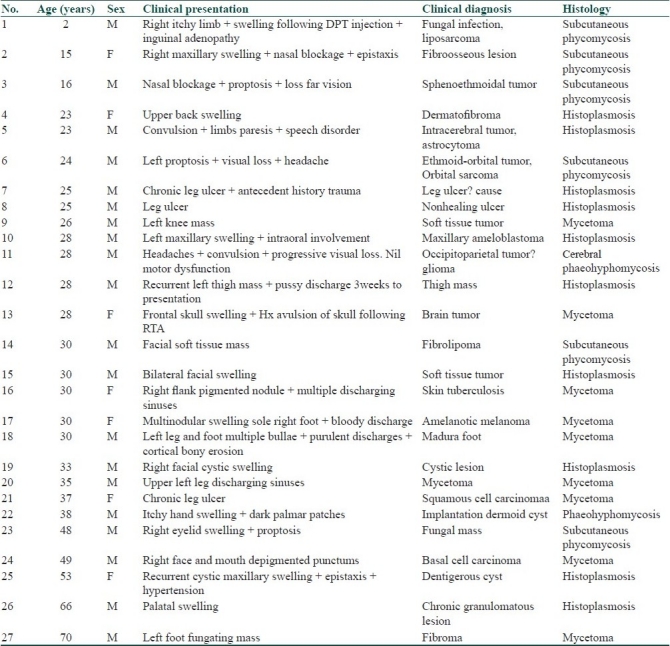

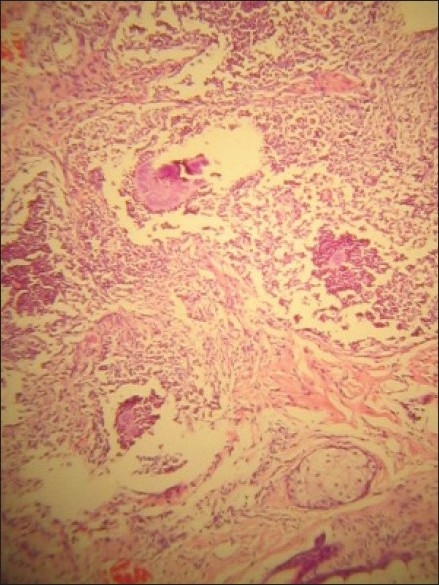

Mycetoma was the second commonest mycosis and accounted for 33.3% of our cases. Its clinical manifestation though varied may be characterized by numerous discharging sinuses containing color specific granules depending on the causative fungi.[1,17] Of the many fungi and actinomycetes implicated in its causation, Madurella mycetomatis accounts for a significant percentage.[18,19] The general mechanism of infection is unclear; however, traumatic implantation from infected soil may occur and exposed body parts are preferentially affected.[1,17–19] This may explain the cases that gave history of trauma. Bony destruction[20] may also occur as seen in the patient with cortical erosion of the small bones of the foot. The duration of infection ranges from 3 to 10 years with an average of 5 years.[21,22] Its diagnosis could be difficult in the absence of discharging sinuses, but can be achieved with a combination of clinical features, granule color examination, histopathological, immunohistochemical, and radiological studies.[22–24] Microbial culture though useful is often limited by the low viability of the causative fungal elements [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Mycetoma showing eosinophilic fungal aggregates surrounded by microabscesses (H and E stain, Magnification ×40)

Figure 2.

Mycetoma showing multiple discharging sinuses

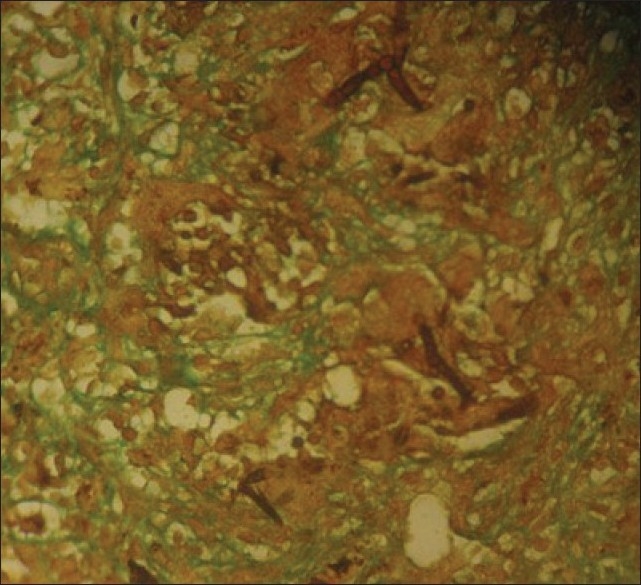

Approximately 20% of the cases were phycomycosis (syn. rhinoentomophthoromycosis, basidiobolomycosis), a localized slow-growing mycotic infection predominant in the tropics and clinically characterized by firm to woody-hard subcutaneous swellings which are site-specific depending on the implicated fungial species [Figure 3].[1] The rhinoentomophthoromycosis (naso-facial) type caused by Conidiobolus coronatus commonly affects the nasal mucosa and sinuses causing gross painless facial swelling which may be associated with visual impairment as seen in our cases. Also, the resulting intranasal granuloma may spread through the ostia, foramina and involve the paranasal sinuses, palate, pharynx, and cheek. While, the basidiobolomycosis caused by Basidiobolus ranarum favors the limbs or limb girdle and often affects children.[1,25] Only one case of our series had preceding history of intramuscular injection with possibly contaminated needle. Histologically, phycomycosis is characterized by large irregular branched septate and aseptate hyphae within multinucleated giant cells and granuloma [Figure 4].[1,26]

Figure 3.

Nasofacial phycomycosis showing broad hyphae within giant cells (magnification ×100, stain: GMS)

Figure 4.

Histoplasmosis spores (PAS stain, Magnification ×100)

Of the two cases of phaeohyphomycosis, one presented as an itchy cystic swelling in the palm while the other had convulsion with progressive visual loss. Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare localized dematiaceous mycosis caused by a group of fungi including Exophiala jeanelmei, Exophiala dermatitidis, Exserohilum rostratum, Bipolaris species, and Alternaria alternate.[26,27] Infection is usually acquired by implantation while histologic diagnosis is based on the presence of obvious brown colored hyphae caused by deposition of dihydroxynaphthalene melanin in the walls.[28] Clinical presentation also depends on the depth of skin infection and systemic manifestation.

Cutaneous deep mycosis in immunocompetent hosts will often elicit distinct histologic inflammatory response characterized by granuloma formation and diagnosis can be achieved with tissue or fluid culture, tissue histology stained with H and E, PAS and GMS, immunohistochemistry, and serology.[29] Serologic testing is the most relevant in establishing diagnosis when culture and stains are unhelpful. However, in resource constraint setting like ours where further delay in institution of therapy increases patient's morbidity, tissue histology with relevant stains remains the main stay of diagnosis. It is also important for clinicians to recognize and know the etiopathogenesis and pathology of these mycoses which should be considered as differentials of cutaneous lesions, especially in the tropics.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Binford CH, Dooley JR. Diseases caused by fungi and Actinomycetes; Deep Mycoses. In: Binford CH, Connor DH, editors. Pathology of tropical and extraordinary diseases. Vol. 2. Washington D.C: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP); 1976. pp. 551–609. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraser RS, Muller NL, Colman N, Pare PD. Diagnosis of disease of the chest. 4th ed. Philadelphia: W.B Saunders; 1999. Histoplasmosis; pp. 876–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farina C, Gnecchi F, Micheti G, Parma A, Cavanna C, Nasta P. Imported and autochthonous histoplasmosis in bergano province, Nothern Italy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:271–4. doi: 10.1080/00365540050165901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wheat J. Endemic mycoses in AIDS: A clinical review. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:146–59. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapotsis GE, Daniil Z, Malagari K, Vamvouka C, Kalomenidis L, Roussos CH, et al. A young male with chest pain, cough and fever. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:506–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00008204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinshaw M, Longley JB. Fungal Diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL, Murphy GF, editors. Lever's histopathology of the skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. pp. 601–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez LR, Raimer SS. Panniculitis, Inclusions, Fungi and Parasites. In: Sanchez LR, Raimer SS, editors. Landes Bioscience vademecum Dermatopathology. Georgetown Texas, USA: Landes Bioscience; 2001. pp. 179–84. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin RA, Jr, Des Prez RM. State of the art: Histoplasmosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;117:929–56. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.117.5.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair PS, Vijayadharan M, Vincent M. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2000;66:151–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas AO. Cutaneous manifestations of African histoplasmosis. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:435–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1970.tb02203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swick BL, Walling HW. Papular eruption in an HIV infected man.Disseminated histoplasmosis with cutaneous and gastrointestinal involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:255–60. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.2.255-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhagwat PV, Hanumanthayya K, Tophakhane RS, Rathod RM. Two unusual cases of histoplasmosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:173–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.48665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swindells S, Durham T, Johansson SL, Kaufman L. Oral histoplasmosis in a patient infected with HIV: A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:126–30. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez SL, Lopez de Blanc SA, Sambuelli RH, Ronald H, Cornelli C, Lattanzi V, et al. Oral histoplasmosis associated with HIV infection: A comparative study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:445–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wheat LJ, Batteiger BE, Sathapatavongs B. Histoplasma capsulatum infections of the central nervous system: A clinical review. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69:244–60. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199007000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saccente M, McDonnell RW, Baddour LM, Mathis MJ, Bradsher RW. Cerebral histoplasmosis in the azole era: Report of four cases and Review. South Med J. 2003;96:410–6. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000051734.53654.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelzer K, Tietz HJ, Sterry W, Haas N. Isolation of both Sporothrix schenskii and nocardia asteroids from a mycetoma of the forefoot. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1311–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fahal AH, Hassan MA. Mycetoma. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1138–41. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800791107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunaa SA. The aetiology and epidemiology of mycetoma. Sudan Med J. 1994;32:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abd El Bagi ME. New radiographic classification of bone involvement in pedal mycetoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:665–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maiti PK, Ray A, Bandyopadhyay S. Epidemiological aspect of mycetoma from a retrospective study of 264 cases in West Bengal. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:788–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samaila MO, Mbibu HN, Oluwole OP. Human mycetoma. Surg Infect. 2007;8:519–22. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khatri ML, Al-Halali HM, Faouod Khalid M, Saif SA, Vyas MC. Mycetoma in yemen: Clinicoepidemiologic and histopathologic study. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:586–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czechowski J, Nork M, Haas D, Lestringant G, Ekelund L. MR and other imaging methods in the investigation of mycetomas. Acta Radiologica. 2001;42:24–6. doi: 10.1080/028418501127346413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hay RJ, Moore MK. Mycology. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2004. pp. 31.85–31.6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert EF, Khoury GH, Pore RS. Histopathological identification of Entomophthora phycomycosis.Deep mycotic infection in an infant. Arch Pathol. 1970;90:583–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin SC, Sun PL, Ju YM, Chan YJ. Cutaneous phaeohyphomycosis caused by Exserohilum rostratum in a patient with cutaneous T- cell lymphoma. Internat J Dermatol. 2009;48:293–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGinnis MR. Chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis, new concepts, diagnosis and mycology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheat LJ. Laboratory diagnosis of histoplasmosis: Update 2000. Semin Respir Infect. 2001;16:131–40. doi: 10.1053/srin.2001.24243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]