Abstract

Background:

Psoriasis, a common papulo-squamous disorder of the skin, is universal in occurrence and may interfere with the quality of life adversely. Whether extent of the disease has any bearing upon the patients’ psychology has not much been studied in this part of the world.

Aims:

The objective of this hospital-based cross-sectional study was to assess the disease severity objectively using Psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score and the quality of life by Psoriasis quality-of-life questionnaire-12 (PQOL-12) and to draw correlation between them, if any.

Materials and Methods

PASI score denotes an objective method of scoring severity of psoriasis, reflecting not only the body surface area but also erythema, induration and scaling. The PQOL-12 represents a 12-item self-administered, disease-specific psychometric instrument created to specifically assess quality-of-life issues that are more important with psoriasis patients.PASI and PQOL-12 score were calculated in each patient for objectively assessing their disease severity and quality of life.

Results:

In total, 34 psoriasis patients (16 males, 18 females), of age ranging from 8 to 55 years, were studied. Maximum and minimum PASI scores were 0.8 and 32.8, respectively, whereas maximum and minimum PQOL-12 scores were 4 and 120, respectively. PASI and PQOL-12 values showed minimal positive correlation (r = +0.422).

Conclusion:

Disease severity of psoriasis had no direct reflection upon their quality of life. Limited psoriasis on visible area may also have greater impact on mental health.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Psoriasis area and severity index, Psoriasis quality-of-life questionnaire-12, quality of life, PASI

Introduction

Psoriasis, a common and chronic papulo-squamous disorder of the skin, is universal in occurrence. Like other chronic dermatoses, patients’ daily functioning and quality of life can be disturbed by psoriasis.[1,2] Degree of the disease severity may have some reflection on the quality of life. Very few Indian studies[3,4] have enlightened us on this aspect of psoriasis.

The chief object of the present study was to assess objectively the extent of the disease and the quality of life and to draw correlation between them, if any.

Materials and Methods

Place and time

The study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology, MGM Medical College and LSK Hospital, Kishanganj, Bihar, India, from November 2008 to August 2009. This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for the patients were all morphological variants of psoriasis with or without joint involvement, pre-treated or untreated. In case of any dilemma in clinical diagnosis, confirmation was done by histopathological test. Exclusion criteria were: (1) psoriasiform dermatoses due to other etiologies like drugs, etc., (2) psoriatic arthropathy without skin involvement, (3) nail psoriasis without skin involvement, (4) generalized pustular psoriasis de novo without any associated or previous history of psoriatic plaque (5) sebo-psoriasis, palmo-plantar pustulosis or inverse psoriasis presenting alone morphologically without any other classical clinical presentation of psoriasis elsewhere in the skin.

Clinical evaluation

Detailed record of demographic and clinical features was noted in “Case Record Proforma”. Family history was traced in detail. Digital photographs of all the patients were taken and preserved. Microphotographs of the histopathological features were kept when skin biopsy was performed.

Psoriasis areas and severity index score

Psoriasis areas and severity index (PASI) score denotes an objective method of scoring severity of psoriasis, reflecting not only the body surface area but also erythema, induration and scaling.[5] PASI score was measured and recorded in each patient.

Psoriasis quality-of-life questionniare-12 score

Psoriasis Quality-of-life Questionniare-12 (PQOL-12) represents a 12-item self-administered, disease-specific psychometric instrument [Figure 1] created to specifically assess quality-of-life issues that are more important with psoriasis patients.[6] PQOL-12 was detected in each patient for objectively assessing their quality of life.

Figure 1.

The PQOL-12 score: Koo-Mentor Psoriasis Instrument[6]

Results

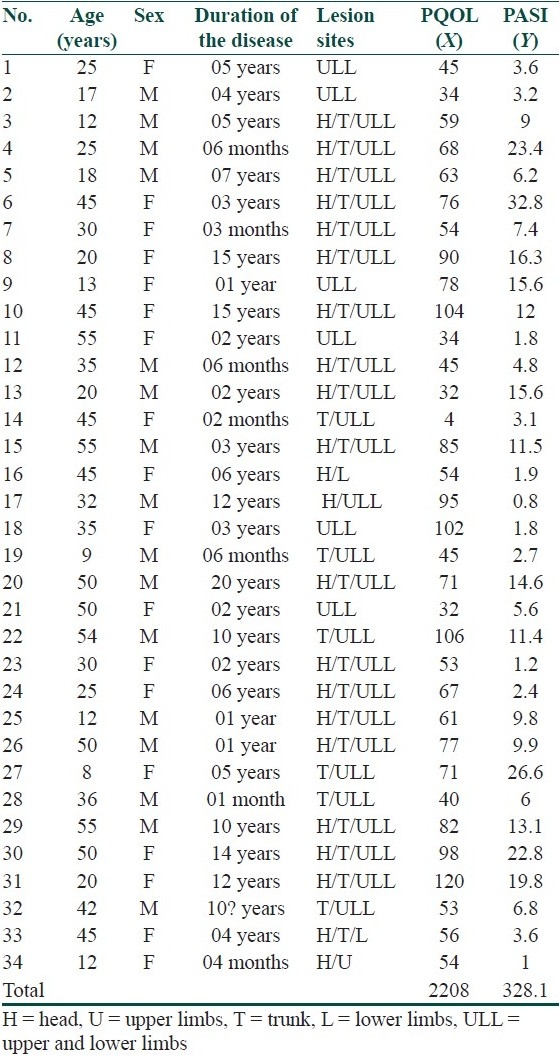

In total, 34 (16 males, 18 females) patients were enrolled in the study. Their age ranged from 8 to 55 years, median being 33.5 years. Duration of disease was from 1 month to 20 years. Maximum and minimum PASI scores were 0.8 and 32.8, respectively, whereas maximum and minimum PQOL-12 scores were 4 and 120, respectively [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age, sex, duration, site with PQOL-12 and PASI in patients

PASI and PQOL-12 values showed [Figure 2] only partial positive correlation (r = +0.422) among themselves.

Figure 2.

Correlation graph between PASI and PQOL-12 value ; XY (scatter) graph showing minimal positive correlation

Discussion

Several studies from abroad have explored the association between clinical severity of psoriasis and quality of life. Finlay,[7] Aschrof,[8] and Gelfand[9] have demonstrated moderate correlation between the extent of the disease and physical disability. A South Indian study[3] has depicted similar finding of positive correlation between PASI and psoriasis disability index (PDI) scores. A study from northern India[4] has also shown that psychiatric morbidity significantly correlated with dysfunction induced by psoriasis.

However, Fortune,[10] Heydendael,[11] and Yang[12] could not find any significant correlation between PASI score and quality of life. Our study also could not show any significant correlation between the extent of the disease and PQOL-12 score.

Severe psoriasis is manifested in different facets, including erythema, infiltration, and desquamation. Fallacy of the PASI score measurement lies in the fact[11] that several quite different patterns of psoriasis can yield similar PASI. Moreover, quality of life may be influenced by a large number of factors including age and co-morbidity. Psoriatic lesions located on visible parts of the body also had a significant impact on the quality of life, especially mental health.[11] Lesions on legs, arms and head had a more profound impact on the quality of life than lesions located on other parts of the body.[1,2]

Cosmetic disfigurement and itching may also determine the burden of the disease,[11] which were not taken into account in the previous disease-specific psychometric instrument created to specifically assess quality-of-life of psoriasis. However, the instrument used in the present study like PQOL-12 has envisaged these two parameters as well.

Our study concludes that disease severity of psoriasis has minimal correlation with quality of life. Even limited psoriasis, especially located on visible parts of the body, may induce great psychological trauma to the patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Finlay AY, Coles EC. The effect of severe psoriasis on the quality of life of 369 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:236–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb05019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Neil P, Kelly P. Postal questionnaire study of disability in the community associated with psoriasis. BMJ. 1996;313:919–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7062.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakesh SV, D’Souza M, Sahal A. Quality of life in psoriasis: A study from South India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:600–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattoo SK, Handa S, Kaur I, Gupta N, Malhotra R. Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis: Prevalence and correlates in India. German J Psychiatry. 2005;8:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.VandeKerkhof PC, Schalkwijk J. Psoriasis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby; 2008. pp. 115–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koo J, Menter A, Lebwohl M, Kozma C, Slaton S, Wojcik A, Kowalski J. The relationship between quality of life and disease severity: results from a large cohort of mild, moderate and severe psoriasis patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1077–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finlay AY, Khan GK, Luscombe DK, Salek MS. Validation of sickness impact profile and psoriasis disability index in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1990;123:751–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb04192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashcroft DM, Li Wan Po A, Williams HC, Griffiths CE. Quality of life measures in psoriasis: A critical appraisal of their quality. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1998;23:391–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.1998.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelfand JM, Feldman SR, Stern RS, Thomas J, Rolstad T, Margolis DJ. Determinants of quality of life in patients with psoriasis: A study from the US population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:704–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortune DG, Main CJ, O’Sullivan TM, Griffiths CE. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: The contributions of clinical variables and psoriasis specific stress. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:755–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heydendael VM, de Borgie CA, Spuls PI, Bossuyt PM, Bos JD, de Rie MA. The burden of psoriasis is not determined by disease severity only. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:131–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2004.09115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y, Koh D, Khoo L, Nyunt SZ, Ng V, Goh CL. The psoriasis disability index in Chinese patients: Contribution of clinical and psychological variables. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:925–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]